Abstract

This study was aimed to investigate the antioxidant capacities of four common forage legume leaves namely, Arachis pintoi (Pintoi), Calapogonium mucunoides (Calapo), Centrosema pubescens (Centro), and Stylosanthes guanensis (Stylo). Two different drying methods (oven-drying and freeze-drying) were employed and antioxidant activities were determined by DPPH, Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) and β-carotene bleaching assays. Total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using Folin-Ciocalteu assay. Freeze-dried extract showed the highest antioxidant activities by DPPH (EC50 values 1.17–2.13 mg/ml), FRAP (147.08–246.42 μM of Fe2+/g), and β-carotene bleaching (57.11–78.60%) compared to oven drying. Hence, freeze drying treatment could be considered useful in retention of antioxidant activity and phenolic content.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Legume leaves, Phenolics, Oven-drying, Freeze-drying

Introduction

Legumes are the earliest plants domesticated by mankind. The popularity of legumes is attributed to its good protein profile (20–30%) compared to usual plant protein sources that ranged lesser than 20% (Bhattacharya and Malleshi 2011; Department of Veterinary Services, Johor 2005; Han and Baik 2008). More interestingly, recent studies have found that consumption of legumes is closely related to reduced risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Flight and Clifton 2006). According to World Health Organization (WHO), CVDs are the world’s largest killers which claimed 17.1 million lives a year (WHO 2009). CVDs are found to be and usually manifest in communities across different age groups. Thus, in order to combat oxidation-linked diseases, a significant role for dietary antioxidants is emerging (Shetty and Wahlqvist 2004).

Antioxidants are important in neutralizing free radicals. Free radicals are generated during normal body metabolism as molecules with incomplete electron pairs which make them more chemically unstable than those with complete electron pair (Fang et al. 2002). The formation of free radicals must be scavenged, as over time exposure to high concentration of free radicals may cause irreversible damage to DNA and other molecules thus leading to chronic diseases. In recent studies, phenolic antioxidant is well recognized as one of the famous dietary plants being applied in designed dietary intervention to manage major oxidation-linked diseases such as diabetes, CVDs, arthritis, cognition diseases and cancers (Wahlqvist 2002). Other than the role in preventive management of diseases, phenolic compounds were found to have protein interaction in the anti-oxidation mechanism. The phenolic compounds integrate a role for easily and readily assimilated sources of protein foods. This is obviously shown in high protein foods such as legume and fish proteins for improved antioxidant response through the proline-linked metabolism (Annegowda et al. 2011; Shetty and Wahlqvist 2004). Therefore, there is substantial interest that has been focused on legumes, particularly on its antioxidants which contribute to its anti-cancer and anti-ageing properties.

Forage legume leaves such as pinto peanut (Arachis pintoi), calapo (Calapogonium mucunoides), butterfly pea (Centrosema pubescens), stylo (Stylosanthes guinensis) are not common for human consumption. However, there is a potential to utilize these legume leaves as food. In fact, phenolics found in various plant extracts other than edible parts are able to prevent oxidative degradation of lipids in food and also help to improve the quality and nutritional value of a particular food (Kähkönen et al. 1999). However, current technologies in food research and development are still facing problems to preserve the maximum phenolic content in food products. Drying method and temperature control are important to ensure antioxidant capacity and stability of polyphenolic compounds (Katsube et al. 2009).

Antioxidant activity of food samples are affected largely based on different drying treatments. Vitamin C, carotenoids, phenolic compounds and antioxidant vitamins are sensitive to heat and light and could easily is destroyed during drying due to thermal degradation and oxidation (Wen et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2008). Hence, novel drying technologies like freeze drying, spray drying, and vacuum drying among others are used (Sagar and Kumar 2010).

Anti-oxidative properties of common legumes have been well documented but antioxidant assessment of legume leaves especially forage legumes is still limited. Also, the impact of different drying treatments on antioxidant capacity of forage legume leaves is scarce. Therefore, the present study was aimed to investigate the influence of freeze drying and oven drying on the antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of selected forage legumes.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Convenience sampling method was used to collect 4 types of legume leaves from Institute of Veterinary, Malaysia, Johor. Legume leaves were Arachis pintoi (Pintoi), Calapogonium mucunoides (Calapo), Centrosema pubescens (Centro), and Stylosanthes guinensis (Stylo). The matured leaves were plucked off from the plant stems. The selection of the leaves was based on color and size to ensure uniformity. Small and pale colored leaves were discarded.

Sample preparation and extraction

Legume leaves (1 kg) was dried in an oven (UM400 Memmert, Germany) at 60 °C for 72 h. The second group of leaves was freeze dried (Oerlikon, Köln, Germany) for 72 h. All dried samples were grinded into fine powder using a food blender (Waring 7011S, Torrington, US) and sieved and stored at - 20 °C until further use. Dried leaves sample (oven- and freeze-dried) of 0.2 g was weighed and transferred into a beaker separately. Then, 20 ml of 80% (v/v) ethanol was added into the beaker. The mixture was stirred at 200 rpm in an orbital shaker (Unimax 1010, Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was then separated from the residue by centrifugation process at 4,500 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was used as sample extract and ready to be used in various analyses. All the extracts were produced in triplicates.

Antioxidant activities determination

DPPH radical scavenging assay

The effect of legume leaves at various concentrations (1, 1.25, 2, 2.5, and 5 mg/ml) on DPPH radical was estimated according to the method of Lee et al. (2007) adopting method of Brand-william et al. (1995) and the results were expressed as EC50. EC50 is defined as the concentration of samples required for degradation of 50% DPPH radicals. The lower the EC50 value indicates higher antioxidant activity. All samples were measured in triplicate.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

This method measures the ferric reducing ability in which a ferric-tripyridyltriazine (Fe3+ - TPTZ) complex was reduced to ferrous (Fe2+) form. The FRAP reagent was prepared according to Azizah et al. (2007) adopting method of Benzie and Strain (1996) and the results were expressed as μM of Fe2+/g sample.

β-carotene bleaching assay

Antioxidant activity of legume leaves and standard (Trolox) was measured according to the method of Amin and Tan (2002). Antioxidant activity (AA) was measured in terms of successful bleaching of β-carotene by using the formula below:

|

where A0 and  are the absorbance values measured at initial time of the incubation for samples and control respectively, while At and

are the absorbance values measured at initial time of the incubation for samples and control respectively, while At and  are the absorbance values measured in the samples or standard and controls at t = 120 min.

are the absorbance values measured in the samples or standard and controls at t = 120 min.

Total phenolic content (TPC)

Total phenolic content was determined according to the method of Singleton and Rossi (1965) with slight modifications. About of 0.2 ml leaf extract (10 mg/ml) was mixed with 1.5 ml Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 min. After that, 1.5 ml of sodium bicarbonate (60 g/L) was added to the mixture and incubated for 90 min at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance was read at 725 nm and result was expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE).

Statistical analysis

All the analysis was carried out in triplicates and the data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data was analyzed by using Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16. One-way ANOVA was used to compare data means for various assays among the samples. Pearson’s correlation test was used to determine the correlations between antioxidant activities and total phenolic content. All analysis was considered at significance level of p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

DPPH scavenging effect

Among the selected samples, the lowest EC50 value was seen in freeze-dried extract (S. guinensis, 1.1 mg/ml) and the highest was seen in oven-dried extract (C. mucunoides, 3.8 ± 0.3 mg/ml, Table 1). Thus, oven-dried extracts exhibited weaker scavenging effect with highest EC50 values. However, despite the high EC50 value in freeze-dried extracts, negative correlation with TPC (r = −0.527, Table 2) was observed. This finding was contradictory with study done by Ozsoy et al. (2008) where EC50 value in Smilax excelsa L. leaves was correlated well with TPC (r2 = 0.7432).

Table 1.

Antioxidant activity of oven dried and freeze dried ethanol extracts of legume leaves evaluated by DPPH assay

| Ethanol extract of legume leaves | EC50 (mg/ml)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Oven-dried | Freeze-dried | |

| Arachis pintoi (Pintoi) | 1.7 ± 0.08bc | 1.6 ± 0.09bc |

| Calapogonium mucunoides (Calapo) | 3.8 ± 0.30e | 2.1 ± 0.13c |

| Centrosema pubescens (Centro) | 3.1 ± 0.18d | 1.6 ± 0.04bc |

| Stylosanthes guinensis (Stylo) | 1.8 ± 0.15c | 1.1 ± 0.13b |

| Ascorbic acid | 0.01 ± 0.0a | |

*The lower the EC50 value, the higher is the antioxidant activity. Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Mean with different letters were significantly different at P < 0.05

Table 2.

Correlation studies between total phenol content and antioxidant assays [DPPH, FRAP and BCB (beta carotene bleaching)] of oven and freeze dried ethanol extracts obtained from legume leaves

| Total phenolic content | Pearson correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | FRAP | BCB | |

| Oven-dried | 0.225 | 0.498 | 0.844** |

| Freeze-dried | −0.527 | −0.201 | 0.424 |

** Significantly different at P < 0.05

Basically, almost all legume leaves showed significant differences in mean of EC50 values except for A. pintoi (Pintoi). As shown in study done by Han and Baik (2008), different legume beans exhibited different antioxidant activities due to the diversity of phytochemical components present in the legumes. Similarly, it is not surprising that the studied legume leaves also showed significant differences in mean of EC50 values among each others with the fact that individual phenolics had different antioxidant activities.

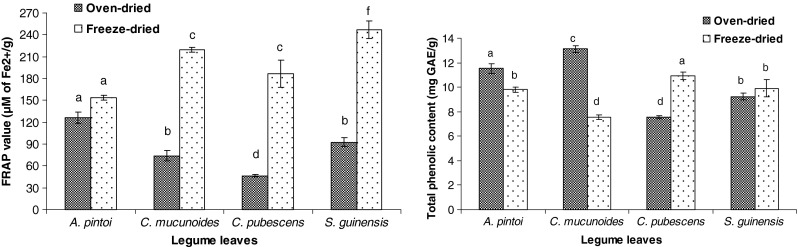

Reducing power

FRAP values were constructed from a standard curve of ferrous sulphate (FeSO4.7H2O) at range of concentration from 200 to 1,000 μM. FRAP values of each samples were calculated from the plotted graph and expressed in μM of Fe2+/g sample. The higher FRAP value indicated the greater reducing power. Figure 1 presents the readings on FRAP values with two different treatments for all legume leaves. The highest FRAP value was seen in freeze-dried, S. guanensis (Stylo) extract (246.42 μM of Fe2+/g) while the lowest was seen in oven-dried C. pubescens (Centro) extract (51 μM of Fe2+/g). All samples showed significant differences in mean FRAP values except A. pintoi (Pintoi).

Fig. 1.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and total phenolic content values of oven dried and freeze dried ethanol extracts obtained from legume leaves (n = 3). Different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05

Moreover, all legume leaves showed significant differences between oven- and freeze-dried samples except A. pintoi. (Pintoi). Chan et al. (2009) explained that thermal treatment resulted in degradation of phenolics and enzymes thus loss in FRAP values significantly. In their study on ginger leaves, oven-drying at 50 °C for 5 h resulted in reduction of FRAP values to more than half as compared to the fresh form. The similar explanation could be applied in this study of legume leaves.

Despite lower FRAP values obtained among oven-dried, extracts, significant moderate correlation (r = 0.498, Table 2) existed between FRAP values and their TPC. A few studies reported moderate to strong correlation (r = 0.906, 0.67, 0.804) between reducing power determined by FRAP assay and the TPC level in various aqueous plant extracts (Dudonne et al. 2009; Koncic et al. 2010; Prasad et al. 2010).

Beta-carotene bleaching activity

Beta-carotene is commonly used to monitor the rate of bleaching. Linoleic acid acts as radical initiator for the bleaching of β-carotene emulsion in the presence of heat or light. Autoxidation occur when β-carotene emulsion fades in colour due to the chain reaction of linoleic acid peroxide (LOO•). Antioxidant acts as hydrogen donor to inhibit the formation of linoleic acid peroxide (LOO•) generated from linoleic acid when exposed to heat (Prior et al. 2005). Blank solution or control is also important in order to eliminate potential interference compounds including food pigments that are detected at wavelength 470 nm (Prior et al. 2005). The trend of antioxidant activities in the inhibition of β-carotene bleaching was not consistent across different treatments. Generally, freeze-dried extracts obtained the highest antioxidant activity (57.1–78.6%) for all legume leaves compared to oven dried extracts (30.5–50%, Table 3).

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity of oven dried and freeze dried ethanol extracts of legume leaves evaluated by β-carotene bleaching assay

| Ethanol extract of legume leaves | Beta carotene bleaching inhibition (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Oven-dried | Freeze-dried | |

| Arachis pintoi . (Pintoi) | 46.6 ± 2.30b | 57.1 ± 4.41d |

| Calapogonium mucunoides (Calapo) | 50.0 ± 1.80bcd | 67.9 ± 3.70e |

| Centrosema pubescens (Centro) | 34.9 ± 3.10a | 75.2 ± 2.15ef |

| Stylosanthes guanensis (Stylo) | 30.5 ± 1.04a | 78.6 ± 3.39f |

| Trolox | 95.4 ± 1.25g | |

Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Mean with different letters were significantly different at P < 0.05

According to Gazzani et al. (1998), temperature and pH may affect the chemical composition and structure of phenolics and thus affect its inhibitory effect on β-carotene bleaching. Apart from that, the standard Trolox significantly contributed to highest antioxidant activity of 95.4%. This indicated that antioxidant activities in legume leaves were significantly lower and unable to compare with Trolox. Only oven dried extracts showed significant strong correlation (r = 0.844, p < 0.01, Table 2) between antioxidant activity and TPC. This revealed that the high antioxidant activities of legume leaves were associated with high TPC. This result indicates the contribution of phenolic in legume leaves toward antioxidant properties in inhibiting formation of linoleic acid peroxide (LOO•).

On the other hand, other group of extracts that utilized freeze-drying methods did not show significant correlation (r = 0.424). This may be due to other possible phytochemicals, flavanoids, polysaccharides which also accounted for high antioxidant activities other than phenolics compounds. Saxena et al. (2007) had also found negative correlation (r = −0.65) between 50% inhibitory effect and total phenolic content in whole and dehusked legumes. Freeze-drying method is able to conserve and enhance majority of the bio-active compounds in plants by the formation of ice-crystals (Chan et al. 2009) and low heat treatments. It is believed that high inhibitory effects shown among freeze-dried samples were attributed from other bio-active compounds such as vitamin C, flavonoids and carotenoids in the current study besides phenolics.

Total phenolic content (TPC)

Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (FCR) is used to measure a sample’s reducing capacity by involving electron-transfer mechanism (Prior et al. 2005). Antioxidant present in legume leaves donated electron to molybdenum (VI) present in FCR that reduced it to molybdenum (V). This reaction could be observed from the colour intensity change from yellow to blue in the concentration-dependent pattern (Prior et al. 2005). Figure 1 presents various level of TPC with regard to the types of legume leaves and their treatment conditions. Highest TPC content was noticed in oven dried extract of C. muconoides (13.1 mg GAE/g), while the lowest was in oven dried extract of C. pubescens (7.5 mg GAE/g). Different from antioxidant capacity analyses, TPC in freeze-dried, extracts did not show higher values for all legume leaves except in C. pubescens (11.1 mg GAE/g) and S. guanensis (9.8 mg GAE/g). This study indicated different drying methods used on different legume leaves had significant effect on the conservation and release of phenolic compounds that contributed to various TPC levels with relation to the composition of phytochemicals in the samples. Some compounds were accelerated with the heat-releasing mechanism (oven-drying) while others would be degraded with the heat treatment.

Several studies reported that TPC in edible legume beans is lower than in legume leaves determined in this study (7.5–13.1 mg GAE/g). Study done by Kähkönen et al. (1999) reported 0.4–1.6 mg GAE/g of total phenolics in peas. Legumes commonly consumed in India denoted 0.24–0.69 mg GAE/g for whole and dehusked legumes (Saxena et al. 2007). There are some other studies done on legumes, groundnut and peas which also showed low TPC in the beans with 1.37 mg GAE/g in legumes (n = 7; black, kidney, mung, soy, small red beans, cowpeas, and peas), 2.18–2.56 mg GAE/g in groundnut and 1.2–2.5 mg GAE/g in peas (green peas, chickpeas, yellow peas) (Cho et al. 2007; Han and Baik 2008; Shad et al. 2009). Apart from that, by comparing the same type of legume, Pinto bean legumes was reported to have 3.76 mg GAE/g (Xu et al. 2007). Its leaves in this study (Arachis sp.) were reported to contain much higher TPC (9.62–11.62 mg GAE/g). Another study on legumes stated that decorticated legumes (removal of seed coat from raw seed) had lower phenolic content than whole legumes (Han and Baik 2008). This implied that disposable parts such as skin and leaves contain higher antioxidant which is in agreement in the study done on chestnut and Etlingera species (Barreira et al. 2008; Chan et al. 2007). On the other hand, legume leaves in this study was found to have comparable phenolic content with fruits such as apple (11.9 mg GAE/g) and berries (12.6 mg GAE/g) (Kähkönen et al. 1999).

Conclusions

All four types of forage legume leaves exhibited strong scavenging effects to DPPH• radicals, strong reducing power, and high β-carotene bleaching inhibitory activities with respect to their phenolic content. The TPC level was also desirable as the values obtained were much higher than the edible beans and also comparable with fruit and berry. Freeze-dried, extracts exhibited excellent antioxidant capacities with higher phenolic content. Hence, freeze drying is highly recommended, than oven drying. Further studies using HPLC/LC-MS method to identify and quantify the main phenolic compounds from these legume leaves is worth investigating.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Institute of Veterinary Malaysia, Johor for providing the legume leaves and Universiti Putra Malaysia for usage of laboratory facilities.

References

- Amin I, Tan SH. Antioxidant activity of selected commercial seaweeds. Maly J Nutr. 2002;8(2):167–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annegowda HV, Bhat R, Tze LM, Karim AA, Mansor SM (2011) The free radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of pod and seed extracts of Clitoria fairchildiana (Howard)—an underutilized legume. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0370-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Azizah O, Amin I, Nawalyah AG, Ilham A. Antioxidant capasity and phenolic content of cocoa beans. Food Chem. 2007;100:1523–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barreira JCM, Ferreira ICFR, Oliveira MBPP, Pereira JA. Antioxidant activities of the extracts from chestnut flower, leaf, skins and fruit. Food Chem. 2008;107(3):1106–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.09.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “Antioxidant Power”. The FRAP Assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Malleshi NG (2011) Physical, chemical and nutritional characteristics of premature-processed and matured green legumes. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0299-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brand-William W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensmittel Wissenschaft and Technologies. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chan EWC, Lim YY, Omar M. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of leaves of Etlingera species (Zingiberaceae) in Peninsular Malaysia. Food Chem. 2007;104(4):1586–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan EWC, Lim YY, Wong SK, Lim KK, Tan SP, Lianto FS, Yong MY. Effects of different drying methods on the antioxidant properties of leaves and tea of ginger species. Food Chem. 2009;113(1):166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Yeum KJ, Chen CY, Beretta G, Tang G, Krinsky NI, Yoon S, Lee-Kim YC, Blumberg JB, Russell RM. Phytonutrients affecting hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidant activities in fruits, vegetables and legumes. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:1096–1107. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nutrient composition of Malaysian feed materials and guides to feeding of cattle and goats. 3. Malaysia: Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dudonne S, Vitrac X, Coutiere P, Woillez M, Merillon JM. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD and ORAC assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:1768–1774. doi: 10.1021/jf803011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang YZ, Yang S, Wu G. Free radicals, antioxidants, and nutrition. Nutr. 2002;18(10):872–879. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)00916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flight I, Clifton P. Cereal grains and legumes in the prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke: a review of the literature. Eur J Clinical Nutr. 2006;60:1145–1159. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzani G, Papetti A, Massolini G, Daglia M. Antioxidative and pro-oxidant activity of water soluble components of some common diet vegetables and the effect of thermal treatment. J Food Chem. 1998;6:4118–4122. doi: 10.1021/jf980300o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han H, Baik BK. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of lentils (Lens culinaris), chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.), peas (Pisum sativum L.) and soybeans (Glycine max), and their quantitative changes during processing. Intl. J Food Sci Technol. 2008;43:1971–1978. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2008.01800.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kähkönen MP, Hopia AI, Vuorela HJ, Rauha JP, Pihlaja K, Kujala TS, Heinonen M. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:3954–3962. doi: 10.1021/jf990146l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsube T, Tsurunaga Y, Sugiyama M, Furuno T, Yamasaki Y. Effect of air-drying temperature on antioxidant capacity and stability of polyphenolic compounds in mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves. Food Chem. 2009;113(4):964–969. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.08.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koncic MZ, Kremer D, Gruz J, Strnad M, Bisevac G, Kosalec I, Samec J, Zegarac P. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of Moltkia petraea (Tratt.) Griseb. flower, leaf and stem infusions. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:1537–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WY, Emmy Hainida KI, Abbe Maleyki MJ, Amin I. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of selected commercially available cruciferous vegetables. Maly J Nutr. 2007;13(1):71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozsoy N, Can A, Yanardag R, Akev N. Antioxidant activity of Smilax excelsa L. leaf extracts. Food Chem. 2008;110(3):571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad KN, Chew LY, Khoo HE, Kong KW, Azlan A, Amin I (2010) Antioxidant capacities of peel, pulp and seed fractions of Canarium odontophyllum Miq. fruit. J Biomed & Biotech, 2010, 1–8. Article id: 871379, doi:10.1155/2010/871379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Prior RL, Wu X, Schaich K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:4290–4302. doi: 10.1021/jf0502698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar VR, Kumar SP. Recent advances in drying and dehydration of fruits and vegetables: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena R, Venkaiah K, Anitha P, Venu L, Raghunath M. Antioxidant activity of commonly consumed plant foods of India: contribution of their phenolic content. Intl J Food Sci Nutr. 2007;58(4):250–260. doi: 10.1080/09637480601121953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shad MA, Perveez H, Nawaz H, Khan H, Ullah MA. Evaluation of biochemical and phytochemical composition of some groundnut varieties grown in arid zone of Pakistan. Pak J Botany. 2009;41(6):2739–2749. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty K, Wahlqvist M. A model for the role of the proline-linked pentosephosphate pathway in phenolic phytochemical biosynthesis and mechanism of action for human health and environmental applications. Asia Pac J Clinical Nutr. 2004;13(1):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. American J Enology Viticult. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlqvist ML. Chronis disease prevention: A life-cycle approach which takes account of the environmental impact and opportunities of food, nutrition and public health policies—the rationale for an eco-nutritional disease nomenclature. Asia Pac J Clinical Nutr. 2002;11:S759–S762. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.s.6.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen TN, Prasad KN, Bao Y, Amin I. Bioactive substance contents and antioxidant activity of blanched and raw vegetables. Innov Food Sci Emerg. 2010;11:464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2010.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) (2009) Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) Fact Sheet No.317, Geneva, September 2009. Accessed on October, 22, 2010 at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/index.html

- Xu BJ, Yuan SH, Chang SKC. Comparative analyses of phenolic composition, antioxidant capacity, and color of cool season legumes and other selected food legumes. J Food Sci. 2007;72:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Zhao M, Shi J, Cheng G, Ruenroengklin N, Jiang Y. Variations in water-soluble saccharides and phenols in longan fruit pericarp after drying. J Food Process Eng. 2008;31:66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4530.2007.00142.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]