Abstract

Paneer, a popular indigenous dairy product of India, is similar to an unripened variety of soft cheese which is used in the preparation of a variety of culinary dishes and snacks. It is obtained by heat and acid coagulation of milk, entrapping almost all the fat, casein complexed with denatured whey proteins and a portion of salts and lactose. Paneer is marble white in appearance, having firm, cohesive and spongy body with a close-knit texture and a sweetish-acidic-nutty flavour. Preparation of paneer using different types of milk and varied techniques results in wide variation in physico-chemical, microbiological and sensory quality of the product. Paneer blocks of required size are packaged in laminated plastic pouches, preferably vacuum packaged, heat sealed and stored under refrigeration. Paneer keeps well for about a day at ambient temperature and for about a week under refrigeration (7 °C). The spoilage of paneer is mainly due to bacterial action. Successful attempts have been made to enhance the shelf life of paneer. This review deals with the history, method of manufacture, factors affecting the quality, physico-chemical changes during manufacture, chemical composition and nutritional profile, packaging and shelf life of paneer.

Keywords: Paneer, Milk, Packaging, Shelf life

Introduction

India is considered as an agrarian country in which major proportion of population is vegetarian. Milk plays an important role in the diet of such persons as a source of animal proteins. India is the largest milk producer in the world with a production of 112 MT, which increased by 3.3 per cent in the last fiscal (Anonymous 2010). About 55% (61.60 MT) of the total production is buffalo milk. Traditional dairy products have played an important role in social, economic and nutritional well being of society. The importance of milk and milk products has been recognized since Vedic times and it is considered to be complete food (Gupta 1999). About half the milk produced is consumed in the liquid form and the remaining is used to prepare products such as ghee, curd, butter, khoa, paneer, cheese, chhana, ice cream and milk powders.

Paneer is an important indigenous product which is obtained by heat treating the milk followed by acid coagulation using suitable acid viz. citric acid, lactic acid, tartaric acid, alum, sour whey. The whey formed is removed to some extent through filtration and pressing. Paneer represents one of the soft varieties of cheese family and is used in culinary dishes/snacks. About 5% of milk produced in India is converted into paneer (Chandan 2007). The estimated market (traditional and organized sectors) of paneer in 2002–03 was worth Rs. 21 crores, and its production was 4,496 metric tones in 2004 (Joshi 2007). Paneer contains all the milk constituents except for loss of some soluble whey proteins, lactose and minerals (Singh and Kanawjia 1988). Paneer has a fairly high level of fat (22–25%) and protein (16–18%) and a low level of lactose (2.0–2.7%) (Kanawjia and Singh 1996). Paneer must be uniform and have a pleasing white appearance with a greenish tinge when made from buffalo milk and light yellow when made from cow milk. Paneer is characterized by a mild acidic flavour with slightly sweet taste, and a soft, cohesive and compact texture. It is an excellent substitute for meat in Indian cuisine.

According to Prevention of Food Adulteration Rules (PFA 2010), Paneer means the product obtained from cow or buffalo milk or a combination thereof by precipitation with sour milk, lactic acid or citric acid. It shall not contain more than 70% moisture and the milk fat content shall not be less than 50% of the dry matter. Milk solids may also be used in preparation of the product. Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS 1983) also specifies a minimum of 50% fat on dry matter basis but a maximum of 60% moisture in paneer. In order to achieve these requirements, buffalo milk having 5–6% fat is deemed to be most suitable (Bhattacharya et al. 1971; Sachdeva and Singh 1988b). Desai (2007) described the desirable sensory attributes for paneer. It must have a characteristic blend of the flavour of heated milk and acid, i.e. pleasant, mildly acidic and sweet (nutty). Its body and texture must be sufficiently firm to hold its shape during cutting/slicing, yet it must be tender enough not to resist crushing during mastication, i.e. the texture must be compact and smooth; Its colour and appearance must be uniform, pleasing white, with a greenish tinge in the case of buffalo milk paneer and light yellow in the case of cow milk paneer.

History of paneer

People during the Kusana and Saka Satavahana periods (AD 75–300) used to consume a solid mass, whose description seems to the earliest reference to the present day paneer (Mathur et al. 1986; Mathur 1991). The solid mass was obtained from an admixture of heated milk and curd (Mathur 1991). The nomads of South West Asia developed distinct heat/acid varieties of cheese (Mathur et al. 1986). Cheese manufactured using high heat and acid precipitation without resorting to use of starter culture (similar to Indian paneer) was practiced in many countries of South Asia and Central South and Latin America. Nomads of the South West Asia regions were probably the first to develop several distinctive cheese varieties. One of the unique Iranian nomadic cheese was called ‘Paneer-khiki’. It was originally developed by the well known ‘Bakhtiari’ tribe that resided in Isfahan in summer and Shraz in winter. The literal meaning of ‘paneer’ is container and ‘khiki’ is skin. The salted version of ‘Paneer-khiki’ was known as ‘Paneer-e-shour’. Paneer is also the Hindi name of the seeds of Withania coagulans, a vegetable rennet that yields a bitter curd. White paneer is a staple food of Nomads in Afghanistan. It is referred to as ‘Paneer-e-khom’ and ‘Paneer-e-pokhta’ when made from raw and boiled milk, respectively (Srivastava and Goyal 2007). A product similar to this is also found in Mexico and Caribbean islands (Torres and Chandan 1981). Paneer is indigenous to South Asia and was first introduced in India by Afghan and Iranian travellers. Earlier milk was coagulated using heat and sour milk or by proteolytic enzymes from creeper like Putika or bark of Palasa (Dhak: Butea frondosa), Kuyala or Jujuka (Jujube) (Chopra and Mamtani 1995).

A product similar to paneer is white unripened cheese made from milk coagulated by rennet or acid referred to as Kareish in Egypt, Armavir in Western Caucasus, Zsirpi in the Himalayas, Feta in the Balkans and Queso Criollo, Queso del Pais, Queso Lianero etc. in Latin America (Torres and Chandan 1981).

Manufacture of paneer

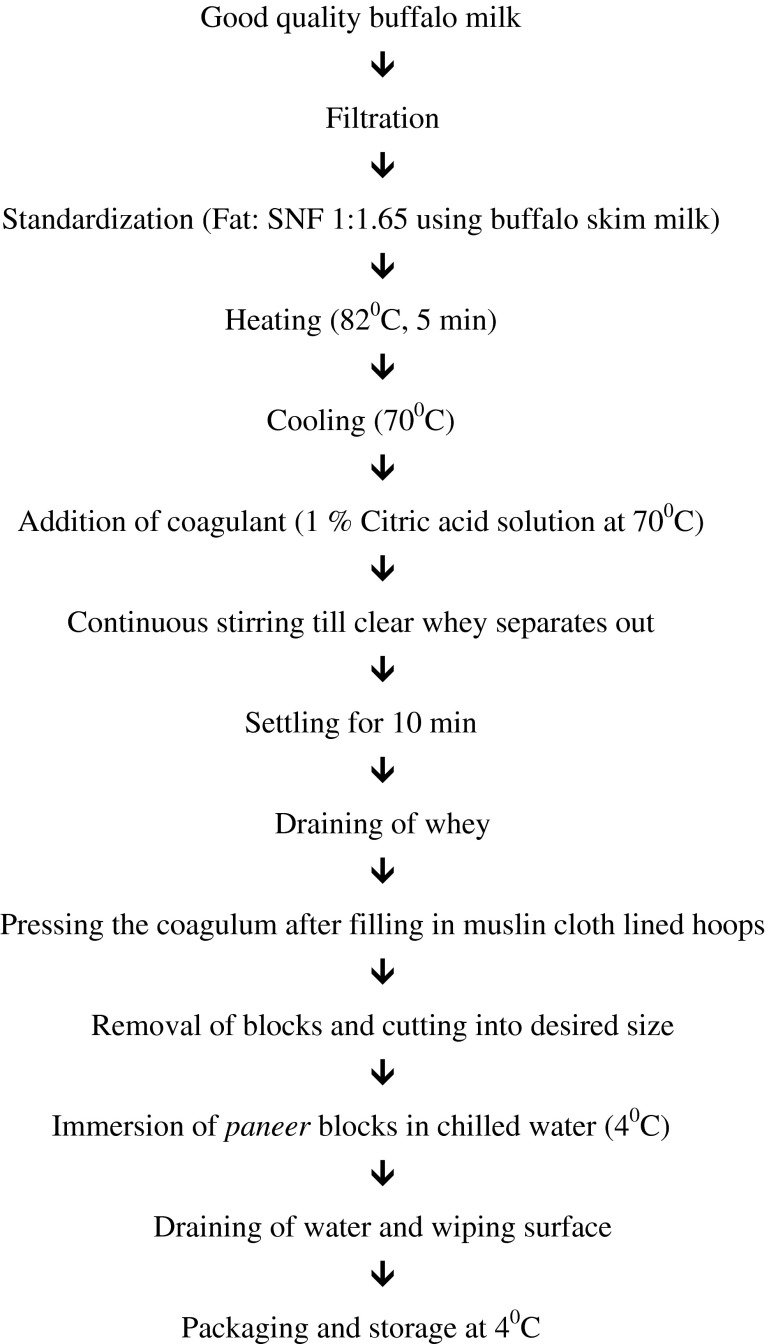

Bhattacharya et al. (1971) standardized the process for manufacturing paneer on a pilot plant scale. Buffalo milk having 6% fat content was heated at 82 °C in a cheese vat for 5 min and cooled to 70 °C, and was coagulated with citric acid (1% solution), which was added slowly to the milk with continuous stirring until a curd and clear whey separated out. The mixture was allowed to settle down for 10 min and the whey was drained out through a muslin cloth. During this time, the temperature of whey was maintained above 63 °C. The curd was then collected and filled in a hoop (35 × 28 × 10 cm) lined with a clean and strong muslin cloth. The hoop had a rectangular frame with the top as well as bottom open. The frame was then rested on a wooden plank and filled with the curd before covering with another plank on the top of the hoop by placing a weight of 45 kg for about 15–20 min. The pressed block of curd is removed from the hoop and cut into 6–8” pieces and immersed in pasteurized chilled water (4–6 °C) for 2–3 h. The chilled pieces of paneer are then removed and placed on a wooden plank for 10–15 min to drain occluded water. Afterwards, these pieces were wrapped in parchment paper, and stored at refrigeration temperature (4 ± 1 °C). A schematic approach for the manufacture of paneer is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for manufacture of paneer

Mechanization of paneer making

An industrial scale paneer manufacturing facility based on the above methodology was developed by the National Dairy Development Board which is commercially used (Aneja 1997). In this process, the milk was heated to 85 °C and cooled to 75 °C in a plate heat exchanger and pumped to a cheese vat for coagulation and preparation as described previously. A continuous paneer making process was developed at National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal by Agrawala et al. (2001). In this system, the unit operations involved in paneer making have been mechanized. The continuous paneer making machine was designed to manufacture 80 kg paneer per hour by employing twin-flanged apron conveyor cum filtering system for obtaining the desired moisture content and texture attributes (Pal and Raju 2007).

Types of paneer

In the last few decades, consistent efforts have been made for the manufacture of different types of paneer like low fat paneer, recombined and reconstituted milk paneer, dietary fiber enriched low fat paneer, soy paneer, filled paneer, vegetable impregnated paneer and UF paneer. A brief description of such types of paneer is given below.

Conventional paneer

Preparation of conventional paneer is an old age practice which is generally adopted by halwais in the cities and towns. For preparation of this type of paneer, generally buffalo milk having a fat to SNF ratio of 1:1.65 is preferred. Such paneer is quite rich in fat content.

Low fat paneer

Generally, health conscious people do not like to consume conventional paneer because of its high fat content. Therefore, efforts have been made to develop low fat paneer without significantly compromising the sensory and textural characteristics. Good quality low fat paneer has been developed at National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal from milk having as low as 3.0% fat (Kanawjia and Khurana 2006). Kanawjia and Singh (2000) reported that fortification of low fat milk with soya solids improved its rheological and sensory quality along with reduction in the cost of production. Chandan (2007) reported that skim milk paneer and low fat paneer having 13% and 24% fat, respectively on dry matter basis are available in the western countries. Out of these, former had a chewy, rubbery texture and hard body.

Recombined and reconstituted milk paneer

During summer season there is a drastic curtailment in the supply of milk due to reduction in milk production, whereas demand is more during these days. As a result, the price of paneer goes up. To overcome the seasonal variation, efforts have been made to develop paneer from milk powder and a fat source. Appropriate technology has been developed for the manufacture of acceptable quality paneer from whole milk powder and also from skim milk powder and butter oil (Kanawjia and Khurana 2006).

Dietary fiber enriched low fat paneer

With increase in the awareness about the health risks associated with consumption of dietary fat and cholesterol intake, there is an increase in the demand of fiber enriched low fat or non fat food products. Since paneer prepared from low fat milk result in hard body, coarse, rubbery and chewy texture, bland flavor, poor mouth feel as well as mottled colour and appearance (Chawla et al. 1985), low fat paneer with an improved quality in terms of sensory, rheological and nutritional attributes has been developed by using soy fiber and inulin (Kanawjia and Khurana 2006). These fibers besides improving the texture and sensory properties of low fat paneer, improves the bowel movement and reduces the chances for colorectal cancer.

Soy paneer

Day by day increase in the cost of milk products has put pressure on researchers for the development of products with high nutritive value but low cost. Soy protein is an outcome of this strategy. This product can be utilized for preparation of various culinary dishes. Babaje et al. (1992) studied the effect of blending soy milk with buffalo milk on the quality of paneer. They observed that coagulation of soy milk results into a white, soft gelatinous mass. The product had bland taste, unique body and texture. Soy paneer is a cheaper source of good quality paneer. They also noticed that addition of soy milk up to 20% to buffalo milk had no adverse effect on the quality of paneer and resembles almost that of milk paneer in colour, taste and springiness. Acceptability of soy paneer can be further enhanced by addition of sodium caseinate.

Filled paneer

During flush season, the rate of the milk goes down and farmers feel difficulty in selling milk at normal price. Under such circumstances, milk fat is generally recovered as cream which is subsequently utilized either for the production of butter or ghee but skim milk does not get right price. To overcome this problem, skim milk can be utilized for preparation of filled paneer. For this skim milk is blended with vegetable oils/vanaspati or coconut milk. Blending of 10% coconut milk with skim milk resulted in the manufacture of filled paneer with highly acceptable sensory attributes (Venkateshwarlu et al. 2003).

Vegetable impregnated paneer

Impregnation of vegetables not only reduces the cost of paneer but also provides functional properties to it. Bajwa et al. (2005) manufactured vegetable impregnated paneer by incorporating coriander and mint leaves from 5 to 30% in buffalo milk having 5% fat. They reported that yield, ash, crude fiber, ascorbic acid, iron and calcium content of the paneer increased with increase in the level of impregnation whereas fat content decreased. A decrease in the level of sensory scores was noticed with increase in the level of vegetables impregnation although all the samples were very well acceptable.

UF paneer

Membrane technologies can be greatly exploited for the manufacture of paneer. It not only improves the quality and shelf life of paneer but also reduces energy losses. Ultrafiltration process permits retention of greater amount of whey solids in paneer and consequently gives higher yields. The process involves standardization of pasteurized milk to a fat content of 1.5% and SNF to 9.0%, followed by ultrafiltration to a total solids content of 30%. To this glucono-δ-lactone is added @ 0.9% prior to filling in retortable metalized polyester pouches. These pouches were then autoclaved for 15 min during which concomitant thermal texturization also took place resulting in formation of long shelf life product (Aneja et al. 2002). UF paneer was reported to a shelf life of 3 months at 35 °C and overall acceptability of 8.5 on a 9-point hedonic scale.

Chemical composition of paneer

The chemical composition of paneer reported by earlier workers showed a significant variation. These differences may be attributed to the differences in the initial composition of milk, method of manufacture and losses of milk solids in whey. The chemical composition of paneer reported by various workers is collated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of paneer

| Type of milk used for paneer making | Constituents (%) | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | Fat | Protein | Lactose | Ash | ||

| Buffalo milk (3.5% fat) | 56.99 | 18.10 | 18.43 | – | – | Chawla et al. (1987) |

| Buffalo milk (4% fat) | 54.05 | 23.27 | 16.78 | 2.69 | 2.20 | Chawla et al. (1987) |

| Buffalo milk (5% fat) | 56.77 | 22.30 | – | – | – | Bhattacharya et al. (1971) |

| Buffalo milk (5% fat) | 52.75 | 25.64 | 15.62 | 2.68 | 2.14 | Kumar et al. (2008b) |

| Buffalo milk (6% fat) | 54.76 | 25.98 | – | – | – | Bhattacharya et al. (1971) |

| Buffalo milk (5.8% fat) | 50.72 | 27.13 | 17.99 | 2.29 | 1.87 | Rajorhia et al. (1984) |

| Buffalo milk (5.5% fat) | 55.19 | 23.80 | 17.99 | – | – | Chawla et al. (1987) |

| Buffalo milk (5.8% fat) | 54.10 | 23.50 | 18.20 | 2.40 | 1.80 | Sachdeva and Singh (1987) |

| Buffalo milk (6% fat) | 50.98 | 27.97 | 14.89 | 2.63 | 2.08 | Kumar et al. (2008b) |

| Whole buffalo milk | 51.52 | 27.49 | 17.48 | 2.28 | 2.18 | Das and Ghatak (1999) |

| Cow milk (3.5% fat) | 55.97 | 18.98 | 20.93 | 2.01 | 1.45 | Mistry et al. (1992) |

| Cow milk (5% fat) | 53.90 | 24.80 | 17.60 | – | – | Singh and Kanawjia (1988) |

| Cow milk (4.5% fat) | 55.26 | 24.15 | 18.43 | – | – | Syed et al. (1992) |

| Buffalo milk and soya milk (50:50) | 54.60 | 18.33 | 19.81 | – | 1.68 | Babaje et al. (1992) |

Factors affecting the quality of paneer

Type of milk

Buffalo milk is better suited for making paneer compared to cow because the latter produces soft, weak and fragile product that is considered unsuitable for cooking purposes. The superior quality of paneer from buffalo milk is due to its unique physico-chemical properties as compared to those of cow milk. Buffalo milk has larger fat globules and casein micelles, higher concentrations of solid fat, casein, calcium, phosphorus, and lower voluminosity and salvation properties of casein micelles compared to cow milk (Sindhu 1996). Cow milk paneer has a soft and spongy body and a relatively open texture whereas, buffalo milk paneer has firm and spongy body and a close texture.

Of all the milk constituents, fat exerted the greatest influence on the quality of paneer. Normally, 5% fat in milk is required for making paneer, which complies with the PFA standards. Bhattacharya et al. (1971) and Kumar et al. (2008a) reported that the good quality paneer could be made from buffalo milk containing 6% fat. However, an acceptable quality paneer was made from milk containing 3.5% fat (Chawla et al. 1985). Mixed milk (cow: buffalo; 1:1) having 5% fat yielded superior paneer than cow milk alone. About one third of buffalo milk could be substituted with cow milk without compromising on flavour, body and texture of resultant paneer (Sachdeva et al. 1985).

Quality of milk

Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1985) noticed that homogenization of cow milk improved the yield and organoleptic score of paneer. They also reported that the milk with Clots-On-Boiling (COB) test positive or milk having high acidity was not suitable for paneer making. Chawla et al. (1985) reported that the use of homogenized buffalo milk, or homogenized buffalo skim milk mixed with unhomogenized cream, did not improve the flavour of low fat paneer. Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1986) reported that fat loss in whey increased with increase in fat content of milk and total solids recovery was highest in paneer from lower fat milk. De et al. (1971) reported that acidic milk having a titratable acidity (TA) of 0.20–0.23% yields a product with inferior quality. They further reported that on use of milk having TA greater than 0.28%, the flavour of the paneer becomes unacceptable and cannot be masked even by incorporating added flavours.

Type, strength and amount of coagulant required

Various coagulants were used, over the years including aged whey (Singh et al. 1984; Sachdeva et al. 1985; Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan 1985), citric acid (Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan 1985; Sachdeva et al. 1985), whey cultured with Lactobacillus acidophilus (Sachdeva et al. 1985), lactic acid (Kumar et al. 2008b) and alum (Kumar et al. 2008c). Grover et al. (1989) prepared soya paneer using citric, tartaric, lactic and acetic acid as coagulant. Paneer made from tartaric acid had the highest acceptability amongst the coagulants. Citric acid as 1% solution is most widely used coagulant for making a good quality paneer (Singh and Kanawjia 1988; Sachdeva and Singh 1988b). Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1985) advocated use of 2% citric acid solution for paneer making from cow milk. The acid (citric/lactic) requirement was 2.34 g for coagulating 1 kg of milk. The quantity of coagulant required was slightly more in case of homogenized milk compared to unhomogenized cow milk (Chawla et al. 1985). The amount of acid required was highest in case of hydrochloric acid and lowest in case of phosphoric acid and acidophilus whey. Citric, tartaric, lactic and sour whey did not show much variation in their requirement to coagulate a given quantity of milk (Sachdeva and Singh 1987).

Pal and Yadav (1991) utilized 1.41 and 1.52 g of citric acid per kg of buffalo milk and cow milk, respectively for complete coagulation, while Chawla et al. (1987) advocated 1.95 g citric acid (1%) for making paneer from 1 kg of cow milk regardless of its fat content. About 1.5 g of hydrochloric acid (0.6%) is sufficient to coagulate buffalo milk for paneer making (Sachdeva and Singh 1987). Rao et al. (1984) made paneer from standardized (6% fat) buffalo milk using three different strengths (0.3, 0.4 and 0.5% solution). The moisture content and thus yield of paneer decreased while acidity and fat losses in whey increased with increasing strength of citric acid solution. Milk heat treated at 85 °C and coagulated with 0.3% citric acid solution gave best result for paneer. Arya and Bhaik (1992) reported that good quality paneer could be made from cow milk (4.5–5.2% fat) by incorporating 0.10% CaCl2 into milk prior to its coagulation.

Heat treatment of milk and coagulation temperature

Heat treatment of milk causes destruction of microorganisms, denaturates whey proteins and retards colloidal calcium phosphate solubility (Ghodekar 1989). Acidification precipitates casein micelles along with denatured whey proteins and insoluble calcium phosphate (Rose and Tessier 1959; Brule et al. 1978; Walstra and Jennes 1983). The temperature-time combinations for heating milk for paneer making advocated by various researchers are: 80 °C without holding (Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan 1985), 82 °C for 5 min (Bhattacharya et al. 1971), 85 °C without holding (Rao et al. 1984), 85 °C for 5 min (Singh et al. 1991) and 90 °C without holding (Sachdeva and Singh 1988b). Coagulation temperature influences the moisture content, fat and TS recovery and thereby the yield of paneer; it also influences its body and texture characteristics. An increase in the temperature from 60 to 86 °C decreased the moisture content of paneer from 59 to 49%. Bhattacharya et al. (1971) recommended cooling of heated (82 °C for 5 min) milk to 70 °C for coagulation. Use of coagulation temperature greater than 70 °C resulted in hard and dry paneer while free surface moisture was evident when coagulated at lower (<70 °C) temperatures (Sachdeva and Singh 1988a). Coagulation temperature of 70 °C has been widely practiced and reported to give desired frying quality in terms of shape retention, softness as well as integrity (Rao et al. 1984; Chawla et al. 1985). Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1985) reported that satisfactory quality paneer can be obtained by employing coagulation temperature of 80 °C from both buffalo and cow milk.

pH of coagulation

De (1980) reported that the moisture retention in paneer decreased with fall in pH, which consequently decreased the yield. Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1985) reported that paneer made by coagulating cow milk at coagulation pH 5.0 was sensorily scored superior to the one coagulated at pH of 5.5. Sachdeva et al. (1991) advocated optimum coagulation pH of 5.2–5.25 for paneer to be prepared from cow milk. Sachdeva and Singh (1988a) noticed that the optimum coagulation pH was 5.35 for paneer obtained from buffalo milk with regard to TS recovery and product quality.

Physico-chemical changes during paneer manufacture

The coagulation process is considered to be a consequence of the chemical and physical changes in casein brought about by the combined influence of heat and acid. This phenomenon involves the formation of large structural aggregates of casein from the normal colloidal dispersion of discrete casein micelles, in which milk fat and coagulated serum proteins get entrapped along with some whey. During this stage, the major changes that take place include: (i) progressive removal of tricalcium phosphate from the surface of casein and its conversion into monocalcium phosphate and soluble calcium salt and (ii) progressive removal of calcium from calcium hydrogen caseinate to form soluble calcium salt and free casein. When the pH of the milk system drops, the colloidal particles become isoelectric i.e. the net electric charge becomes zero to form “Zwiter-ion”. Under such circumstances the dispersion is no longer stable; the casein gets precipitated and forms a coagulum (Ling 1956; Walstra and Jennes 1983). According to Bringe and Kinsella (1986) hydration and steric repulsions between casein micelles are reduced by acidification to facilitate hydrophobic interactions resulting in the coagulation of casein micelles. Iso-electric precipitation of casein may be induced by the addition of calcium as it increases the curd tension by providing closer and more abundant linkage between casein micelles. This mechanism may play a crucial role in the manufacture of a superior quality paneer from buffalo milk compared to cow milk. Calcium content of buffalo milk is higher as compared to cow milk which results in greater linkages between casein micelles which in turn result in firm body and close textured paneer from buffalo milk vis a vis cow milk.

Development of typical rheological characteristics of paneer could be due to preponderant and intensive heat induced protein–protein interactions (Richert 1975). The β-lactoglobulin and κ-casein interact by sulphydryl disulphide interchange when heated together (Sawyer 1969). Interaction between heated κ-casein and β-lactoglobulin as evidenced by electrophoretic changes is initiated at about 65 °C, increasing to a maximum of 83% at 85 °C and decreasing to 76% at 99 °C (Long et al. 1963). However, there are reports that α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin also do interact (Hunziker and Tarassuk 1965) and the complex so formed appears to be able to interact with κ-casein (Baer et al. 1976; Elfagm and Wheelock 1977).

Yield and total solids recovery

Yield of paneer mainly depends on the fat and SNF content of milk as well as on the moisture, fat and protein retained in the paneer. Under optimum conditions yield ranges from 18 to 20%. Total solids recovery in paneer prepared from buffalo milk standardized to 0.1, 3.5, 5.0 and 6.0% fat was 47.08, 57.20, 59.08 and 60.81%, respectively (Bhattacharya et al. 1971). Sachdeva and Singh (1988b) reported that the heat treatment of milk up to 90 °C not only increased the recovery of total solids but also increased the yield of paneer. Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1986) prepared paneer from cow milk standardized to 3.0, 3.5, 4.0 and 4.5% fat by coagulating at 80 °C, using 2% citric acid solution as coagulant. They recorded 61.96, 64.39, 62.89 and 62.98% total solids recovery in paneer and fat loss in whey was 0.12, 0.20, 0.25 and 0.30%, respectively.

Nutritional importance of paneer

Paneer is of great value in diet, especially in the Indian vegetarian context, because it contains a fairly high level of fat and proteins as well as some minerals, especially calcium and phosphorus. It is also a good source of fat soluble vitamins A and D. So its food and nutritive value is fairly high. Superior nutritive value of paneer is attributed to the presence of whey proteins that are rich source of essential amino acids. Due to its high nutritive value, paneer is an ideal food for the expectant mothers, infants, growing children, adolescents and adults. Paneer is also recommended by the clinicians for diabetic and coronary heart disease patients (Chopra and Mamtani 1995).

The protein efficiency ratio (PER) and biological value (BV) of paneer prepared from buffalo milk and cow milk is 3.4, 2.3; 86.56 and 81.88, respectively. The digestibility coefficient values for both types of paneer were nearly identical. Buffalo milk paneer had higher net protein utilization (83.10) as compared to cow milk paneer (78.28) (Srivastava and Goyal 2007).

Evaluation of paneer

The future of any food products mainly depends on its sensory attributes. A 100 point score card is utilized to judge the different sensory attributes of paneer viz. flavour, body and texture, colour and appearance and packaging. The suggested scores on the basis of degree of defects and grades for paneer have been depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Suggested scores of paneer on the basis of degree of defects

| Attribute | Defect | Slight | Definite | Pronounced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavour (50) | Sour/acid | 47 | 43 | 37 |

| Flat | 47 | 43 | 37 | |

| Stale | 47 | 38 | 32 | |

| Smoky/burnt | 46 | 42 | 37 | |

| Bitter | 42 | 38 | 32 | |

| Feed/weed | 42 | 38 | 32 | |

| Foreign | 41 | 36 | 29 | |

| Musty | 41 | 36 | 29 | |

| Putrid | 41 | 36 | 29 | |

| Rancid | 41 | 36 | 29 | |

| Unclean | 41 | 36 | 29 | |

| Yeasty | 41 | 36 | 29 | |

| Body and texture (35) | Crumbly | 32 | 30 | 26 |

| Hard | 32 | 30 | 26 | |

| Rubbery/chewy | 32 | 29 | 24 | |

| Weak | 32 | 29 | 24 | |

| Pasty | 30 | 26 | 18 | |

| Colour and appearance (10) | Dull | 9.5 | 9 | 8 |

| Dry skin | 9 | 8 | 6 | |

| Visible dirt | 8 | 7 | 5 | |

| Uneven surface | 7 | 5 | 3 | |

| Mouldy | 7 | 5 | 3 | |

| Packaging (5) | Damaged | 4.5 | 4 | 3 |

| Soiled/greasy | 4.5 | 4 | 3 |

Paneer having total score of 90 or more = Excellent/A grade, 80–89 = Good/B grade, 60–79 = Fair/C grade, 59 or less = Poor/D grade

Sensory quality of paneer

The flavor score of paneer decreased with decrease in the fat content of original milk utilized for the same. The panelists could not differentiate flavor profile of paneer made from 5.0 to 6.0% fat milk (Bhattacharya et al. 1971). Paneer made from milk standardized to even 3.5 and 5.0% fat has been reported to yield good body and texture. Skim milk yields a very hard bodied paneer. Sensory score of paneer decreased with an increase in the strength of citric acid solution for a specific heat treatment meted to milk (Rao et al. 1984). Sachdeva et al. (1991) observed that the addition of 0.08% calcium chloride to cow milk encouraged the development of paneer with compact, sliceable, firm, cohesive body and a closely knit texture. Use of sodium alginate or pregelatinized starch did not help in improving the quality of the filled paneer (Roy and Singh 1994).

Microbiological quality of paneer

The microbiological quality of paneer depends upon the post manufacture conditions, particularly, handling, packaging and storage of the product. Spoilage of paneer during storage is mainly due to the growth of spoilage organisms on the surface. Increase in total plate, yeast and mould and coliform counts in stored paneer were studied by several workers. Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1985) carried out microbiological analysis of 8–24 h old market samples and laboratory made paneer. Out of the 54 samples, only 15 had less than 5,000 microorganisms per g and were rated as very good. However, none of the samples was of poor quality as none contained more than 200,000 microbes per g. The microbiological standards for paneer as suggested by Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1985) are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Microbiological standards for paneer

| Parameters | Count/g | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Plate Count | <5,000 | Excellent |

| 5,000–50,000 | Good | |

| 50,000–200,000 | Fair | |

| >200,000 | Poor | |

| Coliform count | <10 | Satisfactory |

| >10 | Unsatisfactory |

Vishweshwaraiah and Anantakrishnan (1985)

Sachdeva and Singh (1990) observed the microbiological characteristics of paneer stored at 8–10 °C and reported that total plate count related well with its spoilage. The fresh paneer samples showed that the initial count ranged from 2.3 × 104 to 9.0 × 104 cfu/g. The total plate count of the spoiled samples ranged from 1.58 × 106 to 4.5 × 107 cfu/g. The initial yeast and mould count of fresh samples varied over a narrow range of 3.5 × 102 to 5.2 × 102 cfu/g, while at the time of spoilage it ranged from 5.3 × 103 to 6.3 × 104 cfu/g. Rao et al. (1992) observed that the fresh paneer prepared under strict conditions did not contain organisms capable of producing diseases in human beings. Coliforms, yeasts and moulds were completely destroyed during heating of milk at 82 °C for 5 min but these contaminating organisms may reappear in the paneer through different sources if strict sanitary conditions are not followed during chilling or packaging from unsterilized utensils, unwholesome water or packaging material itself.

Singh and Singh (2000) analyzed the market samples of paneer collected from Agra city and found comparatively lower total plate count (6.51 log10 cfu/g), coliform count (3.05 log10 cfu/g), yeast and mould count (2.99 log10 cfu/g), Enterococcus count (2.73 log10 cfu/g) and Micrococcus count (2.03 log10 cfu/g) for laboratory made samples against 18.00, 10.39, 7.54, 5.05 and 5.07 log10 cfu/g, respectively for market samples. They concluded that the poor bacteriological quality of market samples was mainly due to the use of poor quality milk, unhygienic practices during manufacturing, handling and storage of product.

Packaging

Paneer being a perishable commodity is highly susceptible to physicochemical and microbiological changes. Therefore, its packaging must provide protection against these damages while maintaining its quality, sales appeal, freshness and consumer convenience. Various packaging materials utilized for packaging of paneer include polythene sachets, coextruded films, laminates, parchment paper etc. Most of the paneer produced in organized sector is packaged in polyethylene bags because of its better barrier properties in respect of loss of moisture. These bags prove to be a superior packaging material for paneer compared to vegetable parchment paper (Rao et al. 1984). Packaging of chemical preservatives treated paneer with and without vacuum extended its shelf life up to 35 and 50 days, respectively at 8 °C (Singh and Kanawjia 1990). Vacuum packaging of cow milk paneer is reported to have enhanced its shelf life from 1 week to more than 30 days at 6 °C (Sachdeva and Prokopek 1992). Paneer packaged in high barrier film (EVA/EVA/PVDC/EVA) under vacuum and heat treated at 90 °C for 1 min had a shelf life of 90 days under refrigeration. Rao et al. (1984) prepared paneer from standardized buffalo milk having 6% fat and packaged in polyethylene and vegetable parchment paper and then stored at 6–8 °C. They found that decrease in moisture content of paneer was more in the samples packaged in vegetable parchment paper than in polyethylene. The titratable acidity was also found to be slightly more in parchment paper packed samples than in other packaging materials.

Shelf life

A relatively shorter shelf life of paneer is considered to be a major hurdle in its production at commercial level. It cannot be stored for more than 1 day at room temperature in tropical countries. Bhattacharya et al. (1971) reported that paneer could be stored for only 6 days at 10 °C without much deterioration in its quality, though the freshness of the product was lost after 3 days. It has been noticed that the spoilage in paneer occurs due to growth of microorganisms on the surface. A greenish yellow slime formation on the surface of paneer and the discolouration is accompanied with off flavour. Therefore, efforts have been made to curb the surface growth of microorganisms and thereby increase the shelf life of paneer. Dipping of paneer in brine solution may increase the shelf life of paneer from 7 days to 20 days at 6–8 °C (Kanawjia and Khurana 2006).

Arora and Gupta (1980) reported that during storage at −13 °C or −32 °C for 120 days, moisture content tended to decrease, non-protein nitrogen increased and significant changes in fat, total nitrogen content and pH occurred. Storage of paneer at these temperatures did not affect the flavour and appearance significantly but body and texture was deteriorated.

Defects in paneer

Low quality milk, faulty method of production, unhygienic conditions, lack of refrigeration facility and poor storage conditions are mainly responsible for defects in paneer. Measures adopted to prevent defects in the paneer are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Defects in paneer, their causes and prevention

| Defects | Causes | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Flavour | ||

| Sour | Use of stored milk having high titratable acidity. | Use fresh milk having no developed acidity. |

| Addition of excess amount of coagulating agent. | Use proper amount and concentration of coagulating agent | |

| Smoky | Use of smoky fire for heating the milk | Use non-smoky fire for heating the milk. |

| Rancid/oxidized | Hydrolysis of fat by lipase enzyme or oxidation during storage at room temperature | Store the paneer at 4 °C. |

| Stale | Storage of paneer at low temperature for longer duration | Ensure quick retailing and maintain the temperature up to 4 °C |

| 2. Body and texture | ||

| Hard body | Low fat: SNF ratio in milk | Use fresh milk. Standardize fat: SNF ratio to 1:1.65 |

| Excessively high coagulation temperature. | Coagulate the milk at 70 °C. | |

| Coarse texture | Use of highly acidic milk. | Use fresh milk having normal acidity (0.12–0.14%). |

| Inadequate fat content in the milk. | Use milk having optimum fat content. | |

| High coagulation temperature. | Coagulate the milk at optimum temperature. | |

| Too low pH of coagulation | Use optimum pH of coagulation (5.3). | |

| 3. Colour and appearance | ||

| Dry surface | Higher fat percentage in the milk used. | Optimize or lower the fat content of milk. |

| Surface hardening | Paneer exposed to atmospheric air for longer duration | Do not expose the paneer in atmospheric air for longer duration |

| Pack the paneer in good moisture barrier packaging material. | ||

| Visible dirt/foreign matter | Improper straining of milk. | Correct straining of milk |

| Utensils not cleaned properly. | Use properly cleaned utensils. | |

| Handling or transport of paneer in unhygienic manner | Adopt hygienic measures during handling or transport of milk. | |

| Mouldy surface | Storage of paneer under humid condition. | Maintain the humidity of storage chamber. |

| Excessive moisture content in paneer. | Early disposal/marketing of paneer. | |

| Optimize the moisture content in the paneer. | ||

Miscellaneous

Conclusion

Paneer represents a variety of Indian soft cheese, which is used as a base material for the preparation of a large number of culinary dishes and is highly nutritious and wholesome. Most of the paneer is produced in unorganized sector in very small quantities using traditional methods. Reluctance to use modern technological processes has hampered the organized production, profitability and export performance of paneer. Recently some of the organized dairies have taken trials to produce paneer in continuous machines on commercial scale. Shelf life limitation is a major constraint for its large scale production as it is spoiled within 2 days at room temperature or 7–10 days under refrigeration. Use of antimicrobials and natural antioxidants and vacuum packaging of paneer in nylon pouches reasonably increased the shelf life and facilitated distribution and marketing of product.

Contributor Information

Sunil Kumar, Email: sunilskuast@gmail.com.

Zuhaib F. Bhat, Email: zuhaibbhat@yahoo.co.in

References

- Agrawala SP, Sawhney IK, Kumar B, Sachdeva S (2001) Twin flanged apron conveyor for continuous dewatering and matting of curd. Annual Report, National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, p 55

- Aneja RP. Traditional dairy delicacies. New Delhi: Dairy India Yearbook; 1997. p. 382. [Google Scholar]

- Aneja RP, Mathur BN, Chandan RC, Baneerjee AK (2002) Heat acid coagulated products. In: Technology of Indian milk products. A Dairy India Publication, Delhi, India, pp 133–158

- Anonymous (2010) http://www.economictimes.indiatimes.com, 27 July 2010

- Arora VK, Gupta SK. Effect of low temperature storage on paneer. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1980;33:374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Arya SP, Bhaik NL. Suitability of crossbred cow’s milk for paneer making. J Dairying Foods Home Sci. 1992;11:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Babaje JS, Rathi SD, Ingle UM, Syed HM. Effect of blending soymilk with buffalo milk on qualities of paneer. J Food Sci Technol. 1992;29:119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Baer A, Orz M, Blanc B. Serological studies on heat induced interaction of α-lactalbumin and milk proteins. J Dairy Res. 1976;43:4197. doi: 10.1017/S0022029900016009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa U, Kaur J, Sandhu KS. Effect of processing parameters and vegetables on the quality characteristics of vegetable fortified paneer. J Food Sci Technol. 2005;42:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya DC, Mathur ON, Srinivasan MR, Samlik OL. Studies on the method of production and shelf life of paneer (cooking type of acid coagulated cottage cheese) J Food Sci Technol. 1971;8:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- BIS (1983) Bureau of Indian Standards, IS 10484. Specification for paneer. Manak Bhawan, New Delhi

- Bringe NA, Kinsella JE. The effects of pH, calcium chloride and temperature on the rate of acid coagulation of casein micelles. J Dairy Sci. 1986;69(Suppl 1):61. [Google Scholar]

- Brule G, Real Del Sol E, Fauquant J, Fiaud C. Mineral salts stability in aqueous phase of milk: Influence of heat treatments. J Dairy Sci. 1978;61:1225–1232. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(78)83710-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla AK, Singh S, Kanawjia SK. Development of low fat paneer. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1985;38:280–283. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla AK, Singh S, Kanawjia SK. Effect of fat levels, additives and process modifications on composition and quality of paneer and whey. Asian J Dairy Res. 1987;6:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra S, Mamtani R. Say cheese or paneer? Indian Dairyman. 1995;47:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Das D, Ghatak PK. A study on the quality of paneer marketed at greater Calcutta. J Dairying Foods Home Sci. 1999;18:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- De S (1980) Indian Dairy Products. In: Outlines of dairy technology. Oxford University Press, New Delhi, India, p 412

- De S, Bhattacharya DC, Mathur ON, Srinivasan MR. Production of soft cheese (paneer) from high acid milk. Indian Dairyman. 1971;23:224–225. [Google Scholar]

- Desai HK. Sensory profile of traditional dairy products. In: Gupta S, editor. Dairy India. New Delhi: Dairy India Yearbook; 2007. p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Elfagm AA, Wheelock JV. Effect of heat on α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin in bovine milk. J Dairy Res. 1977;44:367–371. doi: 10.1017/S002202990002032X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghodekar DR. Factors affecting quality of paneer—A review. Indian Dairyman. 1989;41:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Grover M, Tyagi SM, Bajwa U. Studies on soy paneer. J Food Sci Technol. 1989;26:194–197. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK (1999) Quality of raw milk in India. In: Advances in processing and preservation of milk. Lecture compendium, National Dairy Research Institute. Karnal

- Chandan RC. Manufacturing of paneer. In: Gupta S, editor. Dairy India. New Delhi: Dairy India Yearbook; 2007. p. 411. [Google Scholar]

- Hunziker HG, Tarassuk NP. Chromatographic evidence of heat induced interaction of α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin. J Dairy Sci. 1965;48:733–734. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(65)88330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S. Making food processing viable. In: Gupta S, editor. Dairy India. New Delhi: Dairy India Yearbook; 2007. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawjia SK, Khurana HK. Developments of paneer variants using milk and non-milk solids. Processed Food Industry. 2006;9:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawjia SK, Singh S. Sensory and textural changes in paneer during storage. Buffalo J. 1996;12:329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawjia SK, Singh S. Technological advances in paneer making Indian. Dairyman. 2000;52:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Rai DC, Verma DN. Effect of different levels of lactic acid on the physico-chemical and sensory attributes of buffalo milk paneer. Indian J Ani Res. 2008;42:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Rai DC, Verma DN. Effect of fat levels on the physico-chemical and sensory attributes of buffalo milk paneer. Indian Vet J. 2008;85:1182–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Rai DC, Verma DN. Influence of different levels of alum on the quality attributes of buffalo milk paneer. Environ Ecol. 2008;26:290–293. [Google Scholar]

- Ling ER. Test book of dairy chemistry. London: Chapman and Hall Limited; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Winkle QV, Gould IA. Heat induced interaction between crude κ-casein and β-lactoglobulins. J Dairy Sci. 1963;46:1329–1334. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(63)89276-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur BN. Indigenous milk products of India: the related research and technological requirements. Indian Dairyman. 1991;42:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur BN, Hashizume K, Musumi S, Nakazawa Y, Watanabe T. Traditional cheese “paneer” in India and soybean food “tofu” in Japan. Jap J Dairy Food Sci. 1986;35:138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry CD, Singh S, Sharma RS. Physico-chemical characteristics of paneer prepared from cow milk by altering its salt balance. Aust J Dairy Technol. 1992;47:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pal D, Raju PN (2007) Indian traditional dairy products: an overview. In: Sovenir, International conference on “Traditional dairy foods” held at National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal from November 14–17, p i-xxvi

- Pal MA, Yadav PL. Effect of blending buffalo and cow milk on the physico-chemical and sensory quality of paneer. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1991;44:327–332. [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of food adultration rules, 1954 (amended up to 2009) New Delhi: Universal Law Publishing Company Pvt Ltd; 2010. pp. 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rajorhia GS, Pal D, Arora KL. Quality of paneer marketed in Karnal and Delhi. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1984;37:274–276. [Google Scholar]

- Rao MN, Rao BVR, Rao JJ. Paneer from buffalo milk. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1984;37:50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rao KVSS, Zanjad PN, Mathur BN. Paneer technology—A review. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1992;45:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Richert SH. Current milk protein manufacturing processes. J Dairy Sci. 1975;58:985. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(75)84670-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Tessier H. Composition of ultrafiltrates from milk heated at 80 to 230 ° F in relation to heat stability. J Dairy Sci. 1959;42:969–980. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(59)90680-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SK, Singh S. Effect of coagulation temperature and hydrocolloids on production and sensory quality of filled paneer. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1994;47:683–687. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva S, Prokopek D. Paneer—an alternative to tofu. DMZ– Lebensmittelindustrie- und- Milchwirtschaft. 1992;113:645–648. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva S, Singh S. Use of non-conventional coagulants in the manufacture of paneer. J Food Sci Technol. 1987;24:317–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva S, Singh S. Incorporation of hydrocolloids to improve the yield, solids recovery and quality of paneer. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1988;41(2):189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva S, Singh S. Optimization of processing parameters in the manufacture of paneer. J Food Sci Technol. 1988;24:142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva S, Singh S. Shelf life of paneer as affected by antimicrobial agents. Part II: Effect on microbiological characteristics. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1990;43:64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva S, Singh S, Kanawjia SK. Recent developments in paneer technology. Indian Dairyman. 1985;37:501. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva S, Prokopek D, Reuter H. Technology of paneer from cow milk. Jap J Dairy Food Sci. 1991;40:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer WH. Complex between β-lactoglobulin and κ-caseins: a review. J Dairy Sci. 1969;52:1347. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(69)86753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu JS. Suitability of buffalo milk for products manufacturing. Indian Dairyman. 1996;48:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Kanawjia SK. Development of manufacturing technique for paneer from cow milk. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1988;41:322–325. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Kanawjia SK (1990) Effect of hydrogen peroxide and delvocid on enhancement of shelf life of recombined milk paneer. Brief Communication, XXIII International Dairy Congress, Vol. II, October 8–12, Montreal

- Singh SP, Singh KP. Quality of market paneer in Agra city. J Dairying Foods Home Sci. 2000;19:54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Kanawjia SK, Sachdeva S. Current status and scope for future development in the industrial production of paneer. Indian Dairyman. 1984;36:581–585. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Balasubramanyam BV, Bhanumurthi JL. Effect of addition of heat precipitated whey solids on the quality of paneer. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1991;44:178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Goyal GK. Preparation of paneer—A review. Indian J Dairy Sci. 2007;60:337. [Google Scholar]

- Syed HM, Rathi SD, Jadhav SA. Studies on quality of paneer. J Food Sci Technol. 1992;29:117–118. [Google Scholar]

- Torres N, Chandan RC. Latin American white cheese—a review. J Dairy Sci. 1981;64:552–557. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(81)82608-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkateshwarlu J, Reddy YK, Kumar S. Preparation of filled paneer by incorporating coconut milk. Indian J Dairy Sci. 2003;56:352–358. [Google Scholar]

- Vishweshwaraiah L, Anantakrishnan CP. A study on technological aspects of preparing paneer from cow’s milk. Asian J Dairy Res. 1985;4:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Vishweshwaraiah L, Anantakrishnan CP. Production of paneer from cow’s milk. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1986;39:484–485. [Google Scholar]

- Walstra P, Jennes R. Dairy chemistry and physics. New York: Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]