Abstract

The hydro distillation method was used in this study to get essential oils (EOs) from cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.), clove (Eugenia caryohyllata) and Elecampane (Inula helenium L.) and the co-hydro distillation method (addition of fatty acid ethyl esters as extraction cosolvents) to get functional extracts (EFs). The MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) and the MBC (Minimum Bactericidal Concentration) were determined on five pathogenic strains (Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium perfringens, Staphylococcus aureus and Toxoplasma Gondi). The results showed that essential oils of cumin and clove and their functional extracts are effective on concentrations from 500 mg/L to 750 mg/L. The essential oils with functional extracts were used on meat samples at three different concentrations: 750, 1,500 and 2,250 μL. The cumin essential oil produced a reduction of 3.78 log UFC/g with the application of 750 μL, the clove essential oil produced a reduction of 3.78 log UFC/g with the application of 2,250 μL and the cumin and clove functional extracts got a reduction of 3.6 log UFC/g. By chromatography, eugenol was identified in the clove oil, cuminaldehyde in the cumin oil and the isoalactolactones and alactolactones in the elecampane oil as main compounds on the chemical composition of the essential oils and functional extracts obtained.

Keywords: Essential oil, Functional extracts, Antimicrobial protection, Red meat

Introduction

The foods most susceptible to microbial contamination are dairy products, chicken and meat, part of the regular consumer’s diet, but they are also a common vehicle for food diseases. Some pathogen bacteria such as Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium perfringens, Staphylococcus aureus and Toxoplasma Gondi have been isolated from these foods (Reuben et al. 2003). Several antimicrobial treatments have been used in the meat industry to decontaminated/inhibit disease causing pathogens and extend shelf-life. These treatments are either synthetic chemicals or antibiotics. Increased awareness about antibiotic resistance and adverse effects of synthetic preservative has revived the search for natural sources of antimicrobials as alternative preservatives in meat products. Previously studied natural antimicrobials in meat products include bacteriocins, lactoferrin, lysozyme, spices, essential oils and variety plant extract. The use of spices as preservatives has increased in recent years; there are some studies (Sema et al. 2007; Souza et al. 2006; Celikel and Kavas 2008) about their use which prove their inhibitory effects. These studies suggest that spices such as clove, cinnamon, cumin and oregano are effective against inoculated microorganisms on read meat, specifically against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Nowadays, food preserving is focused on the use of natural products, and essential oils are a new alternative for natural food protection (Burt 2004). Essential oils are homogeneous mixtures of organic chemical compounds from the same chemical family (Günther 1948; Burt 2004); they are composed of terpenoids, especially monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes. Nevertheless there may be present low molecular weight aliphatic compounds, acyclic esters or lactones (Celikel and Kavas 2008). The essential oils’ chemical composition is affected by some factors as species and subspecies, geographical location, harvest time, part of the plant and extraction methods used (Rasooli 2007). Due to the difference in chemical compound groups in essential oils, it is more likely that their antibacterial activity is not attributed to a specific mechanism, but to several attack mechanisms to the cell with different targets (Burt 2004). It is known these substances act mainly on the cell’s cytoplasmic membrane. The presence of a hydroxyl group is related to the deactivation of enzymes. It is probable that this group causes cell component loss, a change on fatty acids and phospholipids, and prevents energy metabolism and genetic material synthesis (Di Pascua et al. 2005). Cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) is a spice traditionally used as an antiseptic agent, and it also has a powerful antimicrobial activity on different kinds of bacteria, pathogenic and non-pathogenic fungi for humans (De et al. 2003). The main compound of the cumin essential oil is cuminaldehyde (Jayathilakan et al. 2007; Rasooli et al. 2007). Clove (Eugenia caryohyllata) presents antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli y Staphylococcus aureus (Chaieb et al. 2007). The main compound of the clove essential oil is eugenol (88.58%) and β-caryophyllene in lesser amounts; however, up to 36 different compounds have been determined (Burt and Reinders 2003; Jayathilakan et al. 2007; Perrucci et al. 2007). Some essential oils show better bacterial properties when they are applied on meat products (Burt 2004), mainly because of the high fat and/or protein levels in food products which protect the bacteria from the essential oils’ action, that is, the essential oil is dissolved into the food fatty phase, being relatively less available to act against the microorganism than in the watery phase (Rasooli 2007). Meat products can be present in a balanced diet, contributing many important benefitial nutrients (FAO 2008). It has relatively high lipid content. In general, the muscular tissue is an excellent source of vitamin B complex, especially thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, B6 and B12. Lean meat is considered a good source of Iron and Phosphorus, but is usually poor in Calcium (Varnam and Sutherland 1998). From a nutritional point of view, the importance of meat products comes from their high quality proteins, which contain all the essential aminoacids, as well as from the high bioavailability of its minerals and vitamins. Meat is rich in vitamin B12 and Iron (FAO 2008). One of the properties which make it an excellent environment for the development of microorganisms is that meat is a food matrix formed by soluble carbohydrates such as glycogen, lactic acid, amino acids and proteins. Such components may be used by microorganisms as an available source of energy for their metabolism and reproduction (Zea et al. 2004). Meat products’ microbiota include degenerative microorganisms, mainly proteolytic (Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Moraxella, Aeromonas, among others), which produce undesirable changes of color, texture, flavor and odor in the products. Pathogens (Salmonella sp., Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium botulinum, Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter jejuni), can cause public health issues (Brown 2000). There are also some other extrinsic factors affecting the microbial population, such as: technological processes applied in the production of different meat products, use of thermal treatments, packing type and technology (vacuum packing, controlled or modified atmosphere), and product storage conditions (refrigeration or freezing) and distribution (Zea et al. 2004; Reyes et al. 2003).

In this study, the MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) was obtained, as well as the MBC (Maximum Bactericidal Concentration) of the essential oil (EO) and the functional extracts (FE) obtained by hydrodistillation and co-hydro distillation (addition of fatty acid ethyl esters as extraction cosolvent) from species selected thanks to their biological activity on five pathogenic strains (Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC 43888, Salmonella enteritidis Typhimurium ATCC 14028, Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 and Listeria monocytogenes). The essential oils and the active functional extracts were used on meat samples (beef pulp from the shoulder blade) at three different concentrations (750, 1500 and 2250 μL).

Materials and methods

Raw material

The vegetal material used was cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) and clove (Eugenia caryohyllata) provided by Comercial Cordona from Chihuahua, Mexico. The strains used are: (Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC 43888, Salmonella enteritidis Typhimurium ATCC 14028, Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 and Listeria monocytogenes (ATCC strains), taken from the School of Chemical Sciences culture collection of the Chihuahua Autonomous University. The fatty acid ethyl esters used as co-solvents in the co-hydrodistilation process were ethyl caproate E6 (CAS: 123-66-0, 99% Sigma-Aldrich) and ethyl heptanoate E7 (CAS: 106-30-9, 99% Sigma-Aldrich).

Extraction of essential oils (EO) and functional extracts (FE)

The plants of cumin and clove were individually subject to a hydrodistillation process using the modified Schilcher device. Two methods were used to obtain oils: hydrodistillation and co-hydrodistillation. In the former, the plants were immersed in water, where the system was heated up to water’s boiling point. In the latter, the plants were put in contact with water and fatty acid ethyl esters as extraction cosolvents. The esters used were ethyl caproate (E6) and ethyl heptanoate (E7). The system was heated up to boiling point. The homogeneous mixture composed of the essential oil and the fatty acid ethyl ester was called Functional Extract (FE). The operation conditions used in co-hdrydistillation depended on the vegetal material used, according to reported by Hernández-Ochoa (2005). For that process 200 g of vegetal material, 4 L of water and 20 mL of ethyl ester were used for the cumin and the clove.

Microbiological analysis of essential oils (EO) and functional extracts (FE)

The analysis was carried out according to the findings of Cava et al. (2007). Some tubes with sterile trypticase soy broth (BDDIFCO) were prepared and they were inoculated with 1.5 × 108 cel/mL of the different strains. To get such concentration the bacteria were suspended in a phosphate buffer solution until the turbidity comparable to the McFarland 0.5 nephelometer tube was obtained. Subsequently concentrations of 50, 100, 250, 500, 750 and 1000 mg/L of a concentrated absolute ethyl alcohol (2% v/v) (Faga Lab) were added to EO and FE. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was set by observing the growth in the different tubes after 24 h incubation at 37 °C. The MIC was the lowest concentration that caused an inhibition of any visible growth. For determining the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) it was spread on boxes with trypticase soy agar (BDDIFCO) one drop of each of the MIC test tubes where no turbidity was detected (negative tests), incubating the boxes at 37 °C for 24 h. This was made to count the colony-forming units, determining the microorganisms’ MBC.

Application of selected essential oils (EO) and functional extracts (FE) on red meat

The technique described by Fazlara and Najafzahde (2008) and Jayathilakan et al. (2007) was used to apply the selected essential oils and extracts on lean red meat pulp. From the results obtained from the minimum concentrations to avoid the bacteria growth, it was decided to use the most effective minimum oil and extract concentration from all the tests to use as the lowest oil and extract concentration applied on meat. The concentrations used were 750, 1500 and 2250 mg/L taken from a 50 g/L stock solution (Reyes et al. 2003). 10 g meat samples were weighed in sterile containers, and they were stored in sterile glass petri dishes; different concentrations of the selected essential oils and extracts were applied and they were stored in a freezer at 2 °C. A 90 mL volume of previously sterilized phosphates buffer was added to 10 g of meat, which were introduced into a peristaltic homogenizer (Interscience Bag Mixer) for a minute at speed 4 in sterile filter bags (Standar Bag Filter Sterile Interscience). Subsequently, dilutions were made in test tubes (in triplicate), taking a millimeter from the bag’s filter with a sterile micropipette. 1 ml from every dilution was transferred to glass petri dishes and previously sterilized agar was added, the sample was homogenized and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h (Fisher Scientific Isotemp Incubator).

Statistical analysis

To analyze the effect of the the addition of oils and extracts of meat, a one-way ANOVA was used. Tukey was used for analysis of media, using a 0.95% confidence level. Statistical analysis was done using the computational software Minitab (version 14.0). All analysis was done by triplicate.

Results and discussion

Essential oil and functional extract extraction

Cumin and clove EO and FE were obtained by the hydrodistillation and co-hydrodistillation techniques. The results obtained established that the greatest amount of essential oil is obtained by hydrodistillation, with yields of 1.51% for cumin, 8.88% for clove. The results show that water used as a solvent in the extraction is most efficient; however they also show the compatibility of the essential oils and fatty acid ethylic esters with the obtention of perfectly homogeneous solutions in the co-hydrodistillation process.

Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and functional extracts

Control tubes were made to evaluate the ethyl alcohol’s inhibitory effect, with different concentrations (50–2000 mg/L) of this solvent instead of EO and FE of the studied spices. The results showed that this substance inhibited all bacteria at concentrations higher than 1000 mg/L, for that reason, it was decided to use concentrations from 50 mg/L to 1000 mg/L of a concentrated alcohol solution with the EO and FE. In the case of E6 and E7 ethyl esters used as controls, concentrations of 50, 100, 250, 500, 750 and 1000 mg/L were used. The results indicated that E6 ester presented biological activity on all the studied bacteria at a 50 mg/L concentration. Tt was found that E7 ester is only inhibitory for B. cereus at a 50 mg/L concentration. Based on the above it was estimated that E6 ester may have interference in the FE antimicrobial activity with such ester and it was declared that E7 ester does not contribute any kind of biological activity to the Eos when it has MBCs higher to 1000 mg/L, where the MICs and MBCs of the selected plants’ EO and FE with different esters used can be observed. It was found that all EO and FE had biological activity; nevertheless, the clove EO presented more antimicrobial activity. In general, the MIC values for all EO and FE ranged between 100 and 750 mg/L. The group of Gram positive bacteria was the most sensitive; particularly B. Cereus was susceptible to low concentrations of EO and FE. Nychas (1995) points out those Gram positive bacteria are more sensitive than Gram negative to antimicrobial compounds of spice EO, such as phenols, aldehydes, ketones and terpenes. In general, the difference lies in that the Gram negative bacteria cell wall is thinner than the Gram positive’s cell wall; also the Gram negative cell wall has an outer membrane with a high percent of lipids. The presence of this second membrane protects the cell wall taking into account that the cell wall is essential for keeping the cell integrity (Dourou et al. 2009). The results obtained show the antimicrobial potential of the clove EO, which presented inhibition values of 500 mg/L against all the bacteria evaluated. In general, clove FE presented very similar values to the ones determined with oil, except the clove-E6 against L. monocytogenes, since this strain showed a higher resistance against a 750 mg/L concentration. Another exception was the clove-E7 against B. cereus, which was sensitive to a 250 mg/L concentration. The antimicrobial activity shown by the clove EO may be attributed to the presence of Eugenol, since this phenol compound is linked to damage to the bacterial cell envelope (Rhayour et al. 2003). Other minority compounds also possess antimicrobial properties, such as cariophyllene (Ayoola et al. 2008). Thus, Dorman and Deans (2000) state that the oils’ antimicrobial activity is related to the composition of the plant’s volatile oils, the structural configuration of the oils’ constituent compounds and their functional groups and potencial synergistic interactions among the compounds. In the case of cumin EO it was observed that E. coli and S. enteritidis Typhimurium had high MIC levels (750 mg/L). The bacteria against which the lowest inhibition levels were obtained with this oil were L. monocytogenes and B. cereus with 250 and 100 mg/L respectively. About cumin FEs, cumin-E6 showed the same concentrations as the EO for E. coli and S. enteritidis Typhimurium; however, the concentrations for L. monocytogenes and B. cereus duplicated. Cumin-E7 showed low values on the three Gram positive bacteria MICs and on E. coli but not on S. enteritidis Typhimurium. Iacobellis et al. (2005) attribute the cumin EO antimicrobial activity to a high level of culminaldehyde and to other minority compounds that may contribute to the antimicrobial activity, such as β-pinene, limonene and α-pinene.

Application of oil and extract on meat

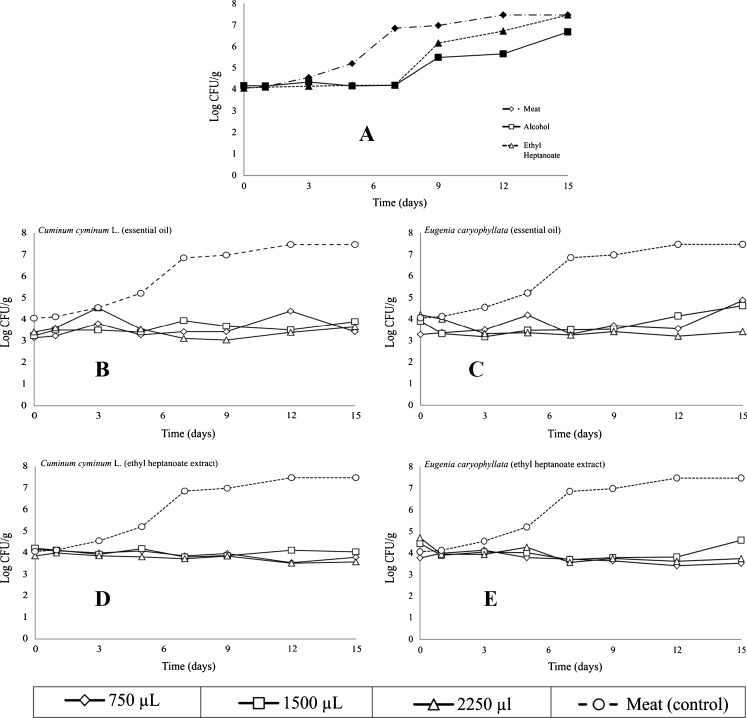

To carry out measurements on meat, 750, 1500 and 2250 μL of EO or EF were applied to 10 gr of meat. Later it was stored at 2 °C. Measurements were carried out on the days 0, 3, 5, 7, 9, 12 and 15. Three controls were used: absolute alcohol, ethyl heptanoate and untreated meat. Results are shown in Fig. 1a. Controls show a clear UFC/g increase on the meat samples during the days analyzed. The alcohol and the ethyl heptanoate exposed a latent inhibition period in bacteria growth during the first days; however, from day 7 on some microorganisms grew, increasing almost reching four logarithmic cycles. At the end of the fifteen days, the three controls showed a very similar microorganism growth, for that reason it was ruled out that the alcohol or the ethyl heptanoate may inhibit and therefore interfere in the effect showed by the the EO and FE used.

Fig. 1.

Effect of application of controls, cumin and clove essential oils and functional extracts on meat’s shelf life. a Three controls, b Essential oil cumin, c Essential oil clove, d Functional extract cumin and e functional extract clove. n = 6

The cumin oil showed bacteria growth inhibition in relation to the control, increasing their lag period as shown in Fig. 1b. It was demonstrated that in the 15-day period the bacterial count presented a 3.78 logarithmic cycle decrease in the UFC/g. Sema et al. (2007) obtained similar results. They point out that cumin essential oil may prolong meat’s shelf life; they also report that some cumin species which present compounds like cuminaldehyde, inhibit the growth and production of some bacteria toxins on meat.

Similar studies show the effectiveness of essential oils such as cumin’s applied to mean samples to prolong their shelf life, inhibiting microorganism growth and measuring the antioxidant activity and therefore increasing the product’s shelf life (Jayathilakan et al. 2007; Kalchayanand et al. 2008). With clove’s essential oil, the concentration that worked best was 2250 μL, since it decreased 3.78 logarhithmic cycles of UFC/g, in comparison to the other two essential oil concentrations. Clove’s EO, the same as cumin’s EO, demonstrated being effective at keeping constant bacteria growth inhibition during the 15 days of measurements (Fig. 1c). The antimicrobial effect shown by clove’s EO can be attributed eugenol, which many authors have reported as responsible for antimicrobial activity (Hammer et al. 1999; Burt 2004; Sema et al. 2007; Perrucci et al. 2007; Celikel and Kavas 2008; López et al. 2009).

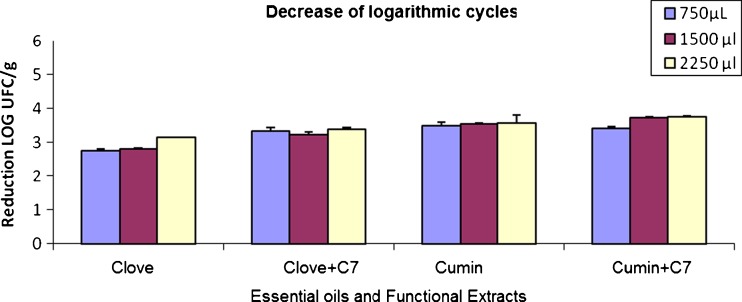

The cumin FE kept the latent growth period or microorganism increase during the 15 days of measurements, which shows it is effective to prolong meat’s shelf life when is applied on meat samples and stored at 2 °C (Fig. 1d). The effect of the decrease of logarhithmic cycles of clove FE with ethyl heptanoate is shown in Fig. 1e, in which the increase of the bacteria lag periodo during the 15 days can be observed. The three concentrations used show the same trend in bacteria growth inhibition. These results show that clove EF obtained with ethyl heptanoate, the same as clove EO applied on meat samples, can be effective to conserve and prolong the products’ shelf life. However, currently not much information is available about the use of essential oils in combination with fatty acid ethyl esters for food protection. In Fig. 2 it can be observed that the best concentration to achieve the highest logarhithmic cycle decrease is 2250 μL. Therefore, the higher the concentration, the better the bactericide effect in the essential oil and functional extracts both of cumin and clove applied on meat samples, maintaining the shelf life during the 15 days sampled. It can be observed that clove EO achieved a lower number of logarhithmic reductions. In spite of that, this oil and extract reduced a greater number of logarhithmic cycles for they manager a reduction of almost 4 log UFC/g. The different functional extract (FE) and essential oil (EO) concentrations showed a bacteriostatical effect to a higher or lesser degree. This confirms any of the four treatments applied on a food matrix such as meat can be effective to keep and prolong the shelf life of meat and other similar products.

Fig. 2.

Logarithmic cycle decrease of the extract and oil concentrations. Each value is mean (n = 6)

Conclusions

The oils which showed a better antimicrobial activity were cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) and clove (Eugenia caryophyllata) alone and in the presence of E7. The funcional exracts obtained with E8 and E9 did not present a noticeable inhibition and the MCB was higher than 1000 mg/L so these extracts were discarded. In all cases the controls showed growth so the alcohol or fatty acid ethyl esters concentration (E6, E7, E8 y E9) was ruled out except as bactericida. The 2250 μL concentration achieved a higher decrease in logarhithmic cycles, therefore the higher the concentration of essential oils and functional extracts, the better the bactericida effect on meat. Essential oils presented a reduction in the number of bacterial cells, demonstrating they can be used to protect a food matrix such as meat, prolonging the bacteria lag period and therefore prolonging its shelf life.

References

- Ayoola GA, Lawore FM, Adelowotan T, Aibinu IE, Adenipekun E, Coker HAB, Odugbemi TO. Chemical analysis and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Syzigium aromaticum (clove) Afr J Microbiol Res. 2008;2:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Burt S. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods-a review. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;94:223–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt S, Reinders R. Antibacterial activity of selected plant essential oils against E. coli O157:H7. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;36:162–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M (2000) Processed meat products, The Microbiological safety and quality of food 1:389–419

- Cava R, Nowak E, Taboada A, Marin-Iniesta F. Antimicrobial activity of clove and cinnamon essential oils against Listeria monocytogenes in pasteurized milk. J Food Protect. 2007;70:2757–2763. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.12.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celikel N, Kavas G. Antimicrobial properties of some essential oils against some pathogenic microorganisms. Czech J Food Sci. 2008;26:174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Chaieb K, Hajlaoui H, Zmantar T, Kahla-Nakbi AB, Rouabhia M, Mahdouani K, Bakhrouf A. The chemical composition and biological activity of clove essential oil Eugenia caryophyllata (Syzigium aromaticum L. Myrtaceae) Phytother Res. 2007;21:501–506. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De M, De AK, Mukhopadhyay R, Banerjee AB, Miró M. Antimicrobial activity of cuminum cyminum L. Ars Pharm. 2003;44:257–259. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pascua R, De Feo V, Villani F, Mauriello G. In vitro antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Mediterranean Apiaceae, Verbenaceae and Lamiaceae against foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria. Ann Microbiol. 2005;55:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Dorman HJD, Deans SG. Antimicrobial agents from plants: antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;88:308–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourou D, Porto-Fett ACS, Shoyer JE, Call GJE, Nychas EK, Luchansky JB. Behavior of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella Typhimurium in teewurst, a raw spreadable sausage. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;130:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2008) Perspectivas alimentarias, Análisis del mercado mundial www.fao.org/docrep/011/ai466s/ai466s00.htm accessed on 19.7.2010

- Fazlara A, Najafzahde LE. The potenttial application of planta essential oils as natural preservatives agains E. coli O157H7. J Agr Food Chem. 2008;11:2054–2061. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2008.2054.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther E (1948) The essential oils: history and origin in plants production analysis (ed) Krieger Publishing New York, pp 235–240

- Hammer K, Carson C, Riley T. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and other plant extracts. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:985–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Ochoa L (2005) Substitution de solvants et matières actives de synthèse par une combine solvant/actif d’origine végétale, Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse (INPT), Toulouse, France. Retrieved from: http://ethesis.inp-toulouse.fr/archive/00000207/01/01/hernandez_ochoa.pdf accessed on 13.2.2010

- Iacobellis NS, Lo Cantore P, Capasso F, Senatore F. Antibacterial activity of Cuminum cyminum L. and Carum carvi L. essential oils. J Agr Food Chem. 2005;53:57–61. doi: 10.1021/jf0487351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayathilakan K, Sharma G, Radhakrishna K, Bawa A. Antioxidant potential of synthetic and natural antioxidants and its effect on warmed over flavour in different species of meat. Food Chem. 2007;105:908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Kalchayanand N, Arthur TM, Bosilevac JM, Brichta-Harhay DM, Guerini MN, Wheeler TL, Koohmaraie M. Evaluation of various antimicrobial interventions for the reduction of escherichia coli O157:H7 on bovine heads during processing. J Food Protect. 2008;71:621–624. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López P, Goñi P, Sánchez C, Gómez Lus R, Becerril R, Nerín C. Antimicrobial activity in the vapour phase of a combination of cinnamon and clove essential oils. Food Chem. 2009;116:982–989. [Google Scholar]

- Nychas GJE. Natural antimicrobials from plants: In New methods of food preservation (Ed) Gould GW. London: Blackie Academic and Proffesional; 1995. pp. 58–89. [Google Scholar]

- Perrucci S, Fichi G, Flamini G, Giovanelli F, Otranto D. Efficacy of an essential oil of Eugenia caryophyllata against Psoroptes cuniculi. Exp Parasitol. 2007;115:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasooli I (2007) Food preservation, a biopreservative approach, food (ed) Global Science Book 1:111–136

- Rasooli I, Gachkar L, Yadegari D, Bagher-Rezaei M, Taghizadeh M, Alipoor-Astaneh S. Chemical and biological characteristics of Cuminum cyminum and rosmarinus officinalis essential oils. Food Chem. 2007;102:898–904. [Google Scholar]

- Rhayour K, Bouchikhi T, Tantaoui A, Sendide K, Remmal A. The mechanism of bactericidal action of oregano and clove essential oils and of their phenolic major components on Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J Essent Oils Res. 2003;15:286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben A, Treminio H, Arias ML, Chaves C. Presencia de Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes y Salmonella spp. en alimentos de origen animal en Costa Rica. Arch Latinoam Nutr. 2003;53:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JE, Aguirre C, Vargas C, Petzold G, Valencia C, Luarte F. Reducción de la contaminación bacteriana en piezas cárnicas de bovino mediante el lavado por aspersión con dióxido de cloro, ozono y Kilol®. Alimentaria. 2003;344:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sema A, Nursel D, Süleyman A. Antimicrobial activity of some spices used in the meat industry. Bull Vet I Pulawy. 2007;51:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Souza EL, Montenegro Stamford TL, Oliveira-Lima E. Sensitivity of spoiling and pathogen food-related bacteria to Origanum vulgare L. (Lamiaceae) essential oil. Braz J Microb. 2006;37:527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Varnam A, Sutherland J. Meat and meat products: technology, chemistry and microbiology. Zaragoza, España: Editorial Acribia S.A; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zea G, Zoraida A, Rios SM. Evaluación de la calidad microbiológica de los productos cárnicos analizados en el Instituto Nacional de Higiene “Rafael Rangel” durante el período 1990–2000. Rev Inst Nac Hig Rafael Rangel. 2004;35:17–24. [Google Scholar]