Abstract

Using phase-separated droplet interface bilayers, we observe membrane binding and pore formation of a eukaryotic cytolysin, Equinatoxin II (EqtII). EqtII activity is known to depend on the presence of sphingomyelin in the target membrane and is enhanced by lipid phase separation. By imaging the ionic flux through individual pores in vitro, we observe that EqtII pores form predominantly within the liquid-disordered phase. We observe preferential binding of labeled EqtII at liquid-ordered/liquid-disordered domain boundaries before it accumulates in the liquid-disordered phase.

Introduction

Pore-forming proteins such as Equinatoxin II (EqtII) play a key role in all kingdoms of life. In bacteria they are important virulence factors (1,2), whereas in mammals they typically play the opposite role and are involved in host immune response (3,4). In general, pore-forming proteins undergo large conformational changes after binding to the target membrane, transitioning from a water-soluble monomer to an inserted multimeric pore with the potential to kill the target cell (2,5). This pore-formation mechanism is often facilitated by a specific, high-affinity receptor such as a transmembrane protein, lipid anchored protein, lipid, or lipid cluster.

EqtII is a member of actinoporin protein family (6–8). In contrast to the more widely studied β-barrel pore-forming toxins, actinoporins insert α-helices to permeabilize target cell membranes. Isolated from the sea anemone Actinia equina, EqtII is believed to play a role in paralyzing prey and defending against predators (6,9). EqtII is a ∼20 kDa protein with high affinity for sphingomyelin (SM)-containing lipid membranes (10,11). EqtII and other actinoporins bind to the lipid membrane through a cluster of exposed aromatic residues and a nearby phosphocholine-binding site (10,12,13). The key step in EqtII pore formation is the conformational change that transfers the N-terminal α-helix across the membrane (12,14). The current model for the EqtII pore is one in which a single pore is formed from three or four monomers (15). Given this small number of contributing monomers but broad distribution of pore conductance (7), it is likely that the pore walls constitute not only α-helices but also a torus of lipids (16). However, recent crystallographic data on the EqtII homolog fragaceatoxin C disagree with this model and suggest a nonameric pore for actinoporins, which would not include membrane lipids (17).

EqtII was previously reported to bind preferentially to domain boundaries in liquid-ordered/liquid-disordered (Lo/Ld) phase coexisting lipid mixtures in both lipid monolayers (18) and giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) (19). In vivo studies also showed that EqtII association with the plasma membrane leads to reorganization of the membrane and formation of microscopic domains, where the toxin preferentially colocalizes with raft proteins (20). In addition, although pore formation by EqtII requires SM (21), SM itself is not sufficient for the N-terminal α-helix conformational change that leads to pore formation (22); another factor is also required. These results led to the suggestion that the presence of lipid domains might play an important role in the pore-formation mechanism, and that EqtII acts not only to form pores but also to remodel the membrane (19).

Here, we investigated the role of Lo/Ld phase separation on EqtII pore formation using droplet interface bilayers (DIBs) (23,24). DIBs are made by contacting nanoliter aqueous droplets in an oil solution in the presence of phospholipids. Lipid monolayers form at each oil/water interface and when two such monolayers touch, a bilayer is created. DIBs can be used to simplify single-molecule fluorescence imaging of a lipid bilayer while retaining gigaohm seals of the membrane (25,26). Using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy of phase-separated DIBs, we observed that EqtII distributed predominantly into the Ld phase, and that pores also formed within this phase. We confirmed previous work showing that EqtII localizes at the Lo/Ld phase boundary, and then examined the time dependence of this phenomenon. We observed preferential accumulation of EqtII in the Ld phase over the Lo phase. These observations support previous measurements on lipid monolayers (18) and conflict with those obtained in GUVs (19). One must always take care when extrapolating results from in vitro experiments to the in vivo action of EqtII. For example, Sezgin and co-workers (27) recently showed that the partitioning of raft proteins is dependent on the preparation method in phase-separated giant plasma membrane vesicles. It is therefore possible that beyond simple demixing, the relative degree of ordering between phases present in these experiments may affect the binding of EqtII to the membrane and hence affect the mechanistic outcome. Such differences might help explain the differences between these observations and those made previously in GUVs.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All materials were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified, and used without further purification. All buffers were filtered before use (0.2 μm cellulose acetate; Nalgene) and buffers used to make DIBs were treated with Chelex 100 ion exchange resin (biotechnology grade, 100–200 mesh; BioRad). 1,2-Diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPhPC), egg SM (eSM; egg, chicken), and cholesterol (Chol; ovine wool) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, and 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiIC18 (3); DiI), 3,3′-dilinoleyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (FAST DiO; DiOC18 (2)), and N-(6-tetramethylrhodaminethiocarbamoyl) 1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (TRITC-DHPE) were obtained from Invitrogen. The calcium indicator Fluo-8H (sodium salt; ABD Bioquest) was used for all experiments imaging the ionic flux through EqtII pores.

Purification, labeling, and characterization of EqtII

An A179C mutant of EqtII was expressed recombinantly in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). This C-terminal mutation has been shown to be amenable to modifications without affecting permeabilizing activity (28). The C-terminus is distant from parts of the molecule that participate in membrane binding (11,12,29) or formation of the final transmembrane pore (14,30) and are likely to be fully exposed to the solvent in both the membrane-bound and pore form of the protein (28,31). EqtII A179C was purified as described previously (32) in the presence of 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) to prevent oxidation of the thiol group. After chromatography, the protein was concentrated by ultrafiltration and washed thoroughly with degassed buffer (20 mM phosphate, pH 7.2) to remove the DTT before labeling with Cy3B maleimide (GE Healthcare). Cy3B maleimide (5 mg mL−1 in dimethyl sulfoxide) was mixed with the A179C solution to a final molar dye/protein ratio of 4:1. The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark at ambient temperature for 2 h. Labeled A179C (EqtII-Cy3B) was separated from the unreacted dye by fast protein liquid chromatography (HiPrep ion exchange; GE Healthcare). Finally, EqtII-Cy3B was concentrated using a Centricon ultrafiltration membrane (3 kDa MWCO; Millipore) to a final concentration of 75 μM. Efficiency of labeling was measured from the absorbance spectrum with a dye/protein ratio of 1.01 ± 0.02. Labeling was also confirmed by SDS-PAGE gel scanned under UV light before Coomassie staining (Fig. S1 A in the Supporting Material).

EqtII-Cy3B activity was assessed via hemolysis of bovine red blood cells as described previously (29). The bovine red blood cells were washed three times with erythrocyte buffer (130 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). Serial twofold dilutions of the protein were made in microtiter plate into a final volume of 100 μL of erythrocyte buffer. The same volume of erythrocyte suspension in erythrocyte buffer (A630 = 0.5) was added to each well and hemolysis was monitored as a decrease in absorption at 630 nm for 20 min at room temperature. The hemolytic activity of the EqtII A179C mutant and Cy3B-labeled mutant (EqtII-Cy3B) was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type protein (Fig. S1 B).

DIBs

DIBs were prepared as described previously (24,25) (Fig. 1). Briefly, 140 μL of molten 0.75% (w:v) low-melting-point agarose was deposited on a plasma-cleaned coverslip by spin coating (30 s at 4000 rpm). A microchannel device was fabricated from polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) (24). The purpose of this device was twofold: 1), to provide multiple wells to contain the oil-lipid solution on top of the agarose-coated coverslip; and 2), to maintain the hydration of the substrate-agarose through contact of the substrate with a network of agarose-filled channels. The microchannel device was placed on top of the coverslip and filled with rehydrating agarose (1.5 M KCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7). Lipid solutions were prepared by drying a film of lipid from chloroform before adding hexadecane. Lipids dissolved in hexadecane were pipetted into the device wells. Solutions of Chol in hexadecane were either pipetted into the wells before bilayer formation or added to the wells after the bilayer was already formed, as indicated in the respective results. Then 50 nL droplets (1.5 M KCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7) were prepared in the hexadecane lipid mixture and pipetted into the microchannel device after 15 min. A lipid bilayer spontaneously formed at the interface between the agarose substrate and the aqueous droplet. For calcium flux imaging, 750 mM CaCl2 was added to the rehydrating agarose solution, and droplets contained 50 μM Fluo-8H and 370 μM EDTA in addition to 1.5 M KCl, 10 mM HEPES, at pH 7.

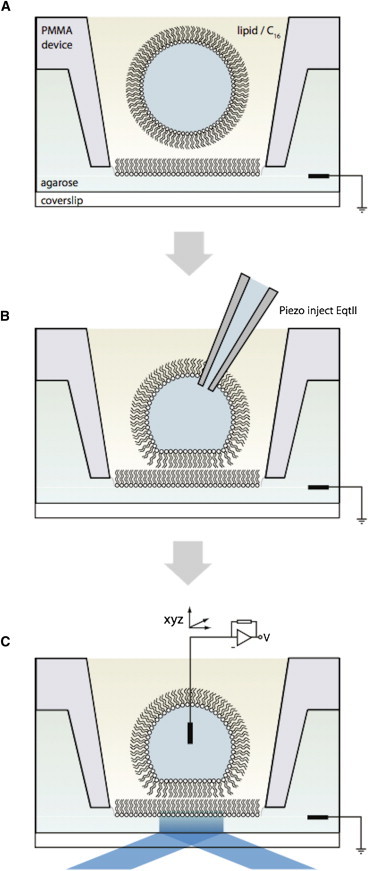

Figure 1.

Schematic. A Droplet Interface Bilayer is formed between an agarose-coated microscope coverslip and an aqueous droplet in a solution of lipids in hexadecane. (A) Monolayers form at droplet/agarose interfaces in a microfabricated device. (B) Piezo-driven nanoinjection from a glass pipette is used to deliver EqtII-Cy3B to the droplet. (C) Insertion of an agarose-coated microelectrode into the droplet permits control of the applied potential, and measurement of gigaohm seal single-channel currents. TIRF microscopy of the bilayer is possible through the coverslip. To see this figure in color, go online.

Droplet nanoinjection

Borosilicate capillaries were pulled to an ∼10 μm inner diameter and backfilled with hexadecane before they were attached to a piezo-driven injector (Nanoliter 2000; World Precision Instruments). Protein solution was loaded into the capillary (typically 200 nL) by piston displacement causing suction. The injector was manipulated into position through the use of a three-dimensional micromanipulator (Narishige, Japan). A set volume of protein solution (usually 4.6 nL) was then introduced into a droplet by bringing the capillary tip into contact with the droplet and ejecting the solution into the droplet as described previously (26).

Fluorescence imaging

We measured fluorescence using an inverted microscope (Ti-E; Nikon). We used 532 nm (Compass 215M; Coherent) and 473 nm (Shanghai Dream Lasers Technology) laser excitation to image Cy3B and DiOC18 (2) fluorescence, respectively. The excitation light was focused at the back aperture of an oil immersion objective lens (60 × Plan Apo N.A. 1.4; Nikon) so that it was totally internally reflected at the coverslip surface. Emitted fluorescence was collected through the same objective, transmitted through suitable dichroic and emission filters (HQ595/50M and HHQ550LP (Chroma) for Cy3B emission, and 525/30 (Semrock) for Fluo8H and DiOC18 (2) emission). Images were recorded with the use of electron-multiplying CCDs (iXon+ DV860E or iXon3 DU860; Andor Technology). Temperature was controlled with a heated microscope stage (PE100; Linkam Scientific Instruments).

Pore diffusion

We determined the location of individual EqtII pores by tracking the position of fluorescent spots corresponding to Ca2+ ion flux through each pore. For spots that moved during an image sequence, we used the Trackmate (33) algorithm compiled for ImageJ (34) (http://fiji.sc/TrackMate) to track all pores present on the bilayer. Individual mean-squared displacements versus time lag were computed for each pore, and the gradient of each plot (4Dlatt) was used to generate a distribution of diffusion coefficients (Fig. 2 D).

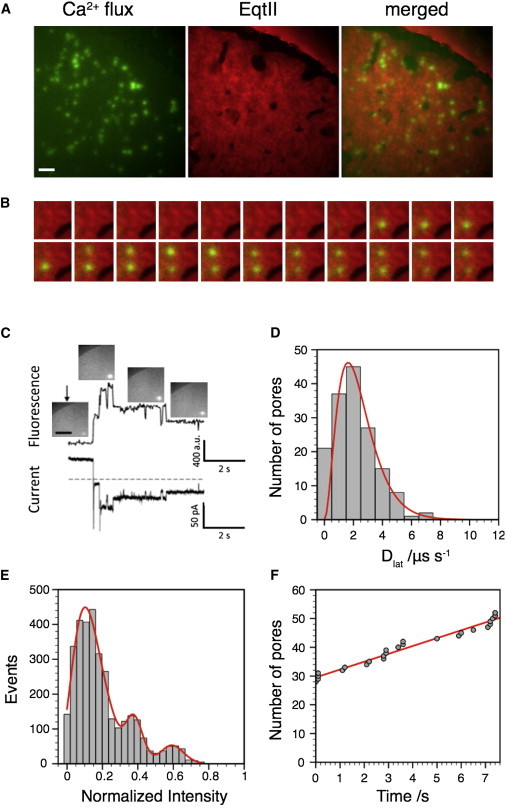

Figure 2.

EqtII-Cy3B pores diffuse and form in the Ld phase. (A) EqtII-Cy3B pores were visualized by the Ca2+ flux using Fluo-8H fluorescence in a DPhPC/eSM/Chol 4:3:3 DIB. The edge of the DIB is visible as an arc in the upper-right quadrant of the images. Pores form in the Ld phase. Scale bar: 10 μm. Also see Movie S1. (B) Image sequence from a 10 × 10 μm region of A, 100 ms per image, running left to right, showing pore appearance in the Ld phase. (C) Simultaneous measurement of Fluo8H Ca2+ flux (top trace) and electrical current (bottom trace) from a single EqtII-Cy3B pore. Inset images show the pore at specific time points; scale bar: 5 μm. Applied potential −60 mV. (D) Pore diffusion from the data set in A was Brownian and fit to a γ distribution of diffusion coefficients (n = 3287). (E) The distribution of pore intensities from the data in A shows distinct peaks. Data were fit to the sum of three log-normal distributions. (F) The rate of pore appearance over the timescale of our experiment was constant. To see this figure in color, go online.

Electrical measurements

An Ag/AgCl electrode in the droplet and an equivalent ground electrode in the agarose enabled electrical measurements and control of transmembrane potential. Currents were recorded with a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B; Axon Instruments) and Windows Electrophysiology Disk Recorder software (WinEDR, John Dempster Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Science). A postacquisition 1 kHz low-pass filter was applied. The microchannel device, electrodes, and patch-clamp head stage were all enclosed in a purpose-built Faraday cage attached to the inverted microscope.

Results

We measured ionic flux through Cy3B-EqtII pores from the localized fluorescence caused by Fluo8H binding to calcium ions as they passed from the substrate agarose through the pore into the droplet. We also measured the time-dependent changes in the distribution of EqtII-Cy3B within DIBs exhibiting liquid-disordered (Ld) and liquid-ordered (Lo) phase coexistence.

EqtII forms pores in the Ld phase

We observed pore formation and diffusion using the Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-8H in the droplet to obtain an optical measurement of ionic flux (35). Under an applied potential difference across the bilayer (−60 mV), calcium ions present in the agarose layer (750 mM) pass through the pore and into the droplet. Chelation of this calcium by Fluo-8H (50 μM) gives rise to a localized fluorescent spot at the location of the pore. The bilayer was illuminated with 473 nm laser light, and the Fluo-8H emission fluorescence due to the calcium flux was imaged at the camera.

DIBs were formed with a lipid composition that exhibited Lo/Ld phase coexistence (4:3:3 DPhPC/eSM/Chol). Using a piezo-driven glass micropipette, we injected 4.6 nL of 10 μM Cy3B-labeled EqtII into the droplet. Cy3B emission was used to determine EqtII location. Pore formation was subsequently observed as the appearance of diffusing spots corresponding to calcium flux across the bilayer (Fig. 2, A and B).

Simultaneous single-channel electrical recording and fluorescence imaging on bilayers at lower EqtII concentration (100 nM) using a bilayer without the complication of phase coexistence (DPhPC:SM 9:1) enabled us to confirm that Fluo-8H spot appearance correlated directly with ionic current through a single EqtII pore (Fig. 2 C).

The bilayer area corresponding to EqtII binding coincided with regions labeled with the Ld marker DiOC18 (2) (Fig. 3 A). Other fluorescent markers of the Ld phase (19,36,37) (DiI and TRITC-DHPE) supported this assignment (Figs. S2 and S4). Lipid mixtures corresponding to the expected two-phase and single-phase regions of the phase diagram also supported this assignment (Fig. S3).

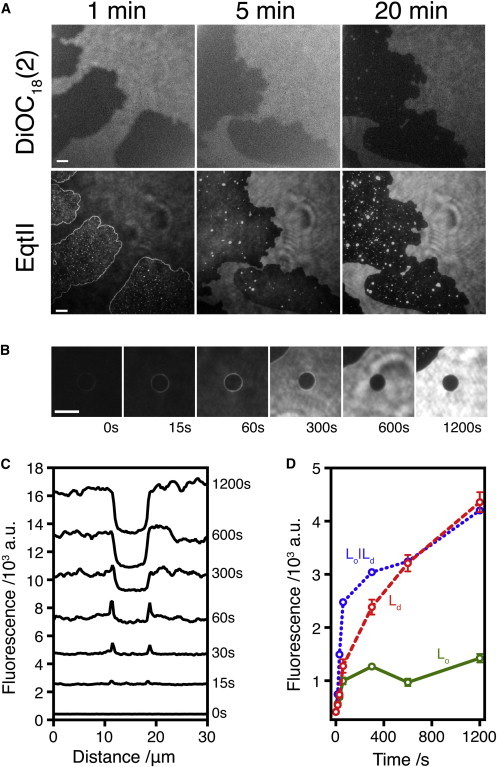

Figure 3.

EqtII-Cy3B preferentially localizes to the domain boundary before being found in the Ld phase. (A) First row: A DPhPC/eSM/Chol 4:1:1 bilayer containing 0.1% DiOC18 (2) as a marker for Ld phase was formed. Second row: EqtII-Cy3B (1 μM) was injected into the droplet to a final concentration of ∼100 nM. (B) Image sequence showing time-dependent accumulation of EqtII fluorescence at the domain boundary. Scale bar: 10 μm. (C) Line profile across the images in B. A relative offset of 2000 a.u. between each trace has been applied for clarity. (D) Time dependence of fluorescence from the images in B taken from three regions of interest (ROIs): inside the central domain (green solid line), at the domain boundary (blue dotted line), and outside the central domain (red dashed line). ROIs are shown in Fig. S5. Error bars represent the SD in pixel intensity for the ROIs. To see this figure in color, go online.

We quantified the preferential location of EqtII pores present in Fig. 2 A by first tracking the location of the pores and then comparing the pore locations with a binary image of EqtII-Cy3B fluorescence. We generated the binary image by applying a threshold to the EqtII-Cy3B image at the intensity corresponding to a minimum population in the histogram of pixel intensities (i.e., between the histogram peaks corresponding to dark and light areas). We assigned 95% (n = 3287) of pore locations to the Ld phase. For those pores assigned to the Lo phase, manual inspection of the original image showed failure of image thresholding to assign small low-contrast features to the correct phase. Pore formation initiated only from within the Ld phase, and not from the phase boundary or the Lo phase (Fig. 2, A and B; Movie S1).

We also examined the diffusive behavior of pores. Within a single experiment, pore diffusion was Brownian, and the distribution of diffusion coefficients (Fig. 2 D) could be fit with a single γ distribution (θ = 0.78 ± 0.03, μ = 2.4 ± 0.1 μm2 s−1). In interpreting this result, we must caution that between different experiments on different bilayers, although diffusion was always Brownian and always described by a single-component distribution, we observed significant variation in the mean diffusion coefficient. We believe these changes correspond to variation in the hydration of the underlying agarose support, as dehydration of the agarose over a period of 24 h resulted in all pores becoming immobile.

The distribution of pore intensities revealed several distinct peaks corresponding to different pore conductances (Fig. 2 E). We observed similar peaks in optical ionic flux for pore formation in the antimicrobial peptide Alamethicin (38). Because these intensity changes are apparent in individual diffusing pores (Fig. 2 C), the most likely explanation is that different-sized EqtII pores are present, although we cannot formally exclude the possibility that multiple pores diffuse in a single diffraction-limited cluster. An assignment of multiple conductance states is consistent with the multiple conductances reported for planar lipid bilayer recordings of EqtII (15). Pore intensity scales linearly with pore current for our applied potential (−60 mV) (Fig. S6).

Once formed, pores persisted throughout the lifetime of our observations (minutes). We did not observe pore closure. Pores appeared at a uniform rate during our measurements (Fig. 2 F). Although we did not attempt to quantify the dependence of pore formation on EqtII, the surface density of the pores did qualitatively increase with the concentration of EqtII-Cy3B added to the droplet. Averaged over all our experiments, the mean bilayer area per pore was 621 μm2 at 100 mM EqtII, whereas at 1 μM EqtII, the mean bilayer area per pore decreased to 52 μm2.

EqtII concentration is first enhanced at the phase boundary and then in the Ld phase

To study more closely the effects of EqtII-Cy3B on bilayers containing two phases, we formed bilayers using a DPhPC/eSM/Chol lipid mixture at a 4:1:1 molar ratio. Subsequently, EqtII-Cy3B (4.6 nL, 1 μM) was injected into the droplet to a final concentration of ∼100 nM, and its localization on the bilayer was observed. At early times, EqtII-Cy3B appeared concentrated at the domain boundaries (Fig. 3 A; Movie S2). Note that, similarly to previous measurements on lipid monolayers (18), the distribution of EqtII-Cy3 fluorescence in the Lo phase appeared uneven. This phenomena was also time dependent, and at early times there was an even and equal distribution of fluorescence in both phases (Movie S2).

Over time, EqtII-Cy3B was found in the same areas as the DiOC18 (2) dye, i.e., the Ld phase (Fig. 3 B). Although transmembrane peptides in general partition into Ld phases in model membranes (39), this result was unexpected because EqtII was previously observed to bind preferentially to the Lo phase (19). The proportion of bilayer area in each phase was also affected by the binding of EqtII to the lipid bilayer: Ld domains shrank and Lo domains increased in size (Fig. 3).

We examined the time dependence of fluorescence intensity. At early times, EqtII-Cy3B was enriched at the phase boundary between the domains (Fig. 3). This is in agreement with previous non-time-dependent observations (18,19). However, after this initial period of enhanced concentration at the phase boundary, we observed that EqtII subsequently increased in concentration in the Ld phase, where protein preferentially accumulates (Fig. 3).

Discussion

We observed that EqtII-Cy3B bound preferentially to the interface between different lipid phases before being found predominantly in the Ld phase (Fig. 3). With the time resolution of our experiments, we did not detect any lag between EqtII binding to Lo and Ld phases, and binding at the Lo/Ld domain boundaries. Our results are consistent with a model in which EqtII binding is SM dependent (10), causing a preferential binding at domain boundaries where imperfect lipid packing is present and SM headgroups may be more exposed. Another potential cause of this preferential binding would be simple saturation of favorable binding sites at the domain boundaries, before accumulation of EqtII from solution to the Ld phase. However, given the apparently equal distribution of EqtII in Ld and Lo phases at early times (Fig. 3 B; Movie S2), followed by an increase of fluorescence in the Ld phase at longer times (Fig. 3 D), we do not favor this interpretation.

After initial binding at the interface, labeled EqtII was found preferentially in the Ld domains (Fig. 3). This result was somewhat unexpected because, although EqtII was previously observed to bind at the lipid interface, it was found to locate preferentially to the Lo phase in GUVs composed of a mixture of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, stearyl-SM, and Chol (19). Given these conflicting results, we cautiously confirmed localization of EqtII to the Ld phase in our lipid system, both by using different fluorescent probes that partition preferentially to the disordered phase (Figs. 3, S2, and S4) and by observing compositions expected to correspond to single- or two-phase regions of the phase diagram (Fig. S3). In agreement with our study, Barlič et al. (18) observed a similar distribution of EqtII in lipid monolayers composed of egg-PC, eSM, and Chol, where EqtII preferentially localized to domain interfaces and the Ld phase.

After localization of EqtII in the Ld phase, we observed subsequent pore formation within the Ld phase by calcium flux imaging and current measurements (Fig. 2, A–C). It has been suggested that protein binding at domain boundaries aids pore formation by increasing the local concentration of toxin monomers (18,19). Here, however, we did not observe pore formation at boundaries, but only within the Ld phase (Movie S2). Pores in the Ld phase were not observed to diffuse into the ordered phase. Pore formation was a relatively rare event, with a significant concentration of nonpore-forming EqtII present in the Ld phase. In agreement with previous work on large unilamellar vesicles (15,40), our data confirm the presence of a large protein pool in the Ld domains, in which pore formation occurs. These observations are also in agreement with a study by Poklar et al. (41), in which no EqtII insertion was observed in ordered bilayers. GUVs that were composed of SM/Chol (1:1 ratio) and in Lo phase were also not susceptible to pore formation, even though EqtII did bind to them (19).

Given the results of these experiments, we suggest two potential models of EqtII action: 1), preferential binding at Lo/Ld domain boundaries followed by helix insertion, diffusion of EqtII into the Ld phase, and then pore formation; and 2), binding at domain boundaries followed by saturation of these binding sites, leading to dominant binding occurring from solution to the Ld phase, and then subsequent insertion and pore formation from the Ld phase.

How might our observations be related to the in vivo action of EqtII? To some extent, EqtII colocalizes in cells with markers for lipid rafts (20), and homologous sticholysin II localizes to detergent-resistant membranes (42). These results might be reconciled if EqtII preferentially binds to the domain boundaries rather than to the Lo domains, or if the Lo/Ld phase coexistence observed in this work is different from that observed in vivo. Clearly, the situation in cells is more complex, as was shown recently in a comparative study that employed EqtII and another SM-specific pore-forming toxin, lysenin, and found three different pools of SM that were stained by either EqtII or lysenin, or both (43).

Segregation at domain boundaries has been reported in a number of systems, including simulations of lipid-packing-driven α-helix segregation (39) and domain formation (44), simulations of lipoproteins (45), and clustering at domain boundaries in nonlipid amphiphiles (46). For example, a combination of two-photon fluorescence microscopy and atomic force microscopy imaging of N-Ras showed preferential binding to Ld domains and at Lo/Ld domain boundaries, similar to what we observed here for EqtII (47). Domain boundaries clearly have a dramatic effect on the mechanism of EqtII pore formation, and these effects have been predicted more generally to play a key role in the preferential adsorption and accumulation of membrane-spanning peptides (39). This domain-dependent mechanism might also be generalized for other pore-forming toxins. For example, the lipid-phase distribution of β-barrel pore-forming toxins appears to depend on hydrophobic mismatch between the bilayer thickness and the protein transmembrane segment, as was recently shown for the pore-forming toxin perfringolysin O (48).

Acknowledgments

N.R. and G.A. received support from the Slovenian Research Agency and Ad Futura, Slovene Human Resources Development and Scholarship Fund. M.I.W. is funded by the ERC and the BBSRC. B.C. is an EPSRC LSI postdoctoral fellow, and J.S.H.D. is a Weidenfeld scholar.

Contributor Information

G. Anderluh, Email: gregor.anderluh@ki.si.

M.I. Wallace, Email: mark.wallace@chem.ox.ac.uk.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Parker M.W., Feil S.C. Pore-forming protein toxins: from structure to function. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2005;88:91–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderluh G., Lakey J.H. Disparate proteins use similar architectures to damage membranes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voskoboinik I., Smyth M.J., Trapani J.A. Perforin-mediated target-cell death and immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:940–952. doi: 10.1038/nri1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert R., Mikelj M., Dalla Serra M., Froelich C., Anderluh G. Effects of MACPF/CDC proteins on lipid membranes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:2083–2098. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez M.R., Bischofberger M., van der Goot F.G. Pore-forming toxins induce multiple cellular responses promoting survival. Cell. Microbiol. 2011;13:1026–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderluh G., Maček P. Cytolytic peptide and protein toxins from sea anemones (Anthozoa: Actiniaria) Toxicon. 2002;40:111–124. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kristan K.C., Viero G., Anderluh G. Molecular mechanism of pore formation by actinoporins. Toxicon. 2009;54:1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-Ortega L., Alegre-Cebollada J., Gavilanes J.G. The behavior of sea anemone actinoporins at the water-membrane interface. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:2275–2288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maček P. Polypeptide cytolytic toxins from sea anemones (Actiniaria) FEMS Microbiol. Immunol. 1992;5:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakrač B., Gutiérrez-Aguirre I., Anderluh G. Molecular determinants of sphingomyelin specificity of a eukaryotic pore-forming toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18665–18677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakrač B., Kladnik A., Anderluh G. A toxin-based probe reveals cytoplasmic exposure of Golgi sphingomyelin. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22186–22195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong Q., Gutierrez-Aguirre I., Anderluh G. Two-step membrane binding by Equinatoxin II, a pore-forming toxin from the sea anemone, involves an exposed aromatic cluster and a flexible helix. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41916–41924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancheño J.M., Martín-Benito J., Hermoso J.A. Crystal and electron microscopy structures of sticholysin II actinoporin reveal insights into the mechanism of membrane pore formation. Structure. 2003;11:1319–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristan K., Podlesek Z., Anderluh G. Pore formation by equinatoxin, a eukaryotic pore-forming toxin, requires a flexible N-terminal region and a stable β-sandwich. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46509–46517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belmonte G., Pederzolli C., Menestrina G. Pore formation by the sea anemone cytolysin equinatoxin II in red blood cells and model lipid membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1993;131:11–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02258530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderluh G., Dalla Serra M., Menestrina G. Pore formation by equinatoxin II, a eukaryotic protein toxin, occurs by induction of nonlamellar lipid structures. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:45216–45223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mechaly A.E., Bellomio A., Guérin D.M. Structural insights into the oligomerization and architecture of eukaryotic membrane pore-forming toxins. Structure. 2011;19:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlič A., Gutiérrez-Aguirre I., González-Mañas J.M. Lipid phase coexistence favors membrane insertion of equinatoxin-II, a pore-forming toxin from Actinia equina. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:34209–34216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schön P., García-Sáez A.J., Schwille P. Equinatoxin II permeabilizing activity depends on the presence of sphingomyelin and lipid phase coexistence. Biophys. J. 2008;95:691–698. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Sáez A.J., Buschhorn S.B., Schwille P. Oligomerization and pore formation by equinatoxin II inhibit endocytosis and lead to plasma membrane reorganization. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37768–37777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakrač B., Anderluh G. Molecular mechanism of sphingomyelin-specific membrane binding and pore formation by actinoporins. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;677:106–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderluh G., Razpotnik A., Norton R.S. Interaction of the eukaryotic pore-forming cytolysin equinatoxin II with model membranes: 19F NMR studies. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;347:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayley H., Cronin B., Wallace M. Droplet interface bilayers. Mol. Biosyst. 2008;4:1191–1208. doi: 10.1039/b808893d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leptihn S., Castell O.K., Wallace M.I. Constructing droplet interface bilayers from the contact of aqueous droplets in oil. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1048–1057. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heron A.J., Thompson J.R., Wallace M.I. Simultaneous measurement of ionic current and fluorescence from single protein pores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1652–1653. doi: 10.1021/ja808128s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson J.R., Cronin B., Wallace M.I. Rapid assembly of a multimeric membrane protein pore. Biophys. J. 2011;101:2679–2683. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sezgin E., Levental I., Schwille P. Partitioning, diffusion, and ligand binding of raft lipid analogs in model and cellular plasma membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:1777–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderluh G., Barlič A., Macek P. Avidin-FITC topological studies with three cysteine mutants of equinatoxin II, a sea anemone pore-forming protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;242:187–190. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malovrh P., Barlič A., Anderluh G. Structure-function studies of tryptophan mutants of equinatoxin II, a sea anemone pore-forming protein. Biochem. J. 2000;346:223–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malovrh P., Viero G., Anderluh G. A novel mechanism of pore formation: membrane penetration by the N-terminal amphipathic region of equinatoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22678–22685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderluh G., Barlič A., Menestrina G. Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis of an eukaryotic pore-forming toxin from sea anemone: topology in lipid membranes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;263:128–136. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderluh G., Pungerčar J., Gubenšek F. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of equinatoxin II. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;220:437–442. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaqaman K., Loerke D., Danuser G. Robust single-particle tracking in live-cell time-lapse sequences. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shuai J., Parker I. Optical single-channel recording by imaging Ca2+ flux through individual ion channels: theoretical considerations and limits to resolution. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:283–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumgart T., Hunt G., Feigenson G.W. Fluorescence probe partitioning between Lo/Ld phases in lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:2182–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stachowiak J.C., Hayden C.C., Sasaki D.Y. Targeting proteins to liquid-ordered domains in lipid membranes. Langmuir. 2011;27:1457–1462. doi: 10.1021/la1041458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harriss L.M., Cronin B., Wallace M.I. Imaging multiple conductance states in an alamethicin pore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14507–14509. doi: 10.1021/ja204275t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schäfer L.V., de Jong D.H., Marrink S.J. Lipid packing drives the segregation of transmembrane helices into disordered lipid domains in model membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:1343–1348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009362108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tejuca M., Serra M.D., Menestrina G. Mechanism of membrane permeabilization by sticholysin I, a cytolysin isolated from the venom of the sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14947–14957. doi: 10.1021/bi960787z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poklar N., Fritz J., Chalikian T.V. Interaction of the pore-forming protein equinatoxin II with model lipid membranes: a calorimetric and spectroscopic study. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14999–15008. doi: 10.1021/bi9916022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alegre-Cebollada J., Rodríguez-Crespo I., del Pozo A.M. Detergent-resistant membranes are platforms for actinoporin pore-forming activity on intact cells. FEBS J. 2006;273:863–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yachi R., Uchida Y., Arai H. Subcellular localization of sphingomyelin revealed by two toxin-based probes in mammalian cells. Genes Cells. 2012;17:720–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2012.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Domański J., Marrink S.J., Schäfer L.V. Transmembrane helices can induce domain formation in crowded model membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:984–994. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janosi L., Li Z., Gorfe A.A. Organization, dynamics, and segregation of Ras nanoclusters in membrane domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:8097–8102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200773109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muddana H.S., Chiang H.H., Butler P.J. Tuning membrane phase separation using nonlipid amphiphiles. Biophys. J. 2012;102:489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicolini C., Baranski J., Winter R. Visualizing association of N-ras in lipid microdomains: influence of domain structure and interfacial adsorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:192–201. doi: 10.1021/ja055779x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin Q., London E. Altering hydrophobic sequence lengths shows that hydrophobic mismatch controls affinity for ordered lipid domains (rafts) in the multitransmembrane strand protein perfringolysin O. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:1340–1352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.