Abstract

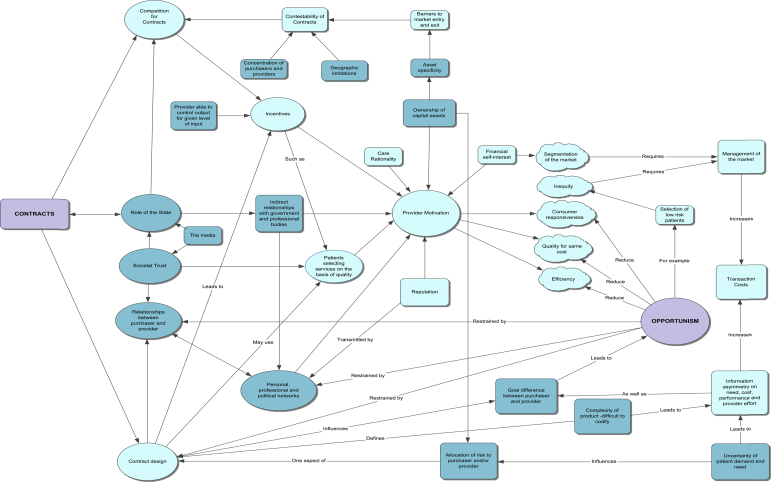

UK NHS contracts mediate the relationship between dental and medical practitioners as independent contractors, and the state which reimburses them for their services to patients. There have been successive revisions of dental and medical contracts since the 1990s alongside a change in the levels of professional dominance and accountability. Unintended consequences of the 2006 dental contract have led to plans for further reform. We set out to identify the factors which facilitate and hinder the use of contracts in this area. Previous reviews of theory have been narrative, and based on macro-theory arising from various disciplines such as economics, sociology and political science. This paper presents a systematic review and aggregative synthesis of the theories of contracting for publicly funded health care. A logic map conveys internal pathways linking competition for contracts to opportunism. We identify that whilst practitioners' responses to contract rules is a result of micro-level bargaining clarifying patients' and providers' interests, responses are also influenced by relationships with commissioners and wider personal, professional and political networks.

Keywords: Contracts, NHS, Dental practice, Medical practice, Opportunism, Theory, Commissioning, Markets

Highlights

-

•

We integrate concepts from 5 grand theories in a logic model.

-

•

The logic model conveys pathways linking contracts to opportunism.

-

•

We identify concepts particularly relevant to UK NHS dental contracts.

-

•

We identify contract responses as influenced by personal, professional and political networks.

Introduction

Ever since the establishment of the NHS in 1948, both medical and dental practitioners have worked as self-employed contractors whilst being remunerated by various fees and/or allowances paid from the general tax fund (Wynes & Baines, 1998). Consequently both types of practitioners have developed commercial and entrepreneurial as well as professional identities; although their relationship with the NHS has meant that they are distinct from private limited companies and thus straddle public and private spheres (McDonald, 2009). Over recent decades however, as NHS health reform has moved to adopt market principles where commercial contracts are awarded to competing providers, this has substantially reduced the degree of professional control held by practitioners over the range and provision of primary care services which they provide (Pollock, Price, Viebrook, Miller, & Watt, 2007). Recent research describes how both doctors (Waring & Bishop, 2013) and dentists (Harris & Holt, 2013) have actively resisted, adapted or captured reforms to accord with their own view of the world.

NHS contracts mediate the relationship between medical (GMPs) and dental (GDPs) practitioners and the state. From the establishment of the NHS in 1948 up until the 1990s, general medical and dental contracts were centrally determined, and whilst regularly adjusted to amend remuneration rates, they remained broadly unchanged and were largely undemanding in terms of performance monitoring. In 1990 a new contract was imposed on both GMPs and GDPs. The 1990 GMP contract introduced a handful of performance targets (McDonald, 2009), whilst for dentists their contract demanded that they give fuller descriptions of treatment to patients in treatment plans, use information leaflets, and guaranteed rights of access to emergency care (Harris & Holt, 2013). Revision of these contracts has been on-going ever since: most significantly with the introduction of locally negotiated and monitored Personal Medical Service and Personal Dental Service contracts in 1997; and in 2004 where new legislation effectively ended the monopoly of GMPs over the provision of primary medical care to the NHS, resulting in an expansion of market forces in primary health care (Pollock et al., 2007). For GDPs a new contract in 2006 enforced a greater accountability to Primary Care Trust (PCT) commissioners, although the contract was later recognised as flawed by the Health Select Committee in 2008 (House of Commons, 2008) because of unintended consequences. Further contextual detail is given in the online Appendix and in Table 1 online.

Continual rounds of contract reform to address loopholes in the contract are expensive not only in terms of transaction costs, but in terms of the social capital between purchasers and providers, the government and the profession. This runs counter to the principle of managed competition which is focused on increasing efficiency and lowering costs. Light (2001) however points out both the errors and corrective mechanisms which occur in shaping contracts are defined by social context and institutional forces. He portrays behavioural responses to contracts as neither rational nor irrational, but interactional and contingent. It follows therefore that practitioners' responses to contracts, often viewed merely as self-interested opportunism, should be viewed within a wider context of organisational resistance to institutional change. As policy makers and the profession plan for a replacement dental contract to be implemented in 2015, we set out to identify the factors which facilitate and hinder the use of contracts to manage and strategically develop UK General Dental Services (GDS), using a comparison with medical practice to highlight factors distinct to dental services. This paper reports on a systematic review of health care contracting theory which was undertaken as part of a wider research programme funded by the National Institute of Health Research.

Study of health care contracting stands at a cross roads of several disciplines: economics, organisational sociology, strategic management, socio-legal studies and political science. In some of these disciplines the focus is on individual providers' responses to incentives (economics), whilst in others (such as the sociological disciplines) there is more of an institutional focus. Theory of health care contracting has been described from a number of these perspectives, and has previously been reported as narrative reviews focused at a macro-theory level, which is broad in scope (Ferlie & McGivern, 2003). What is missing is some work which provides integration across macro-theories, as well as the detail of lower level theory and concepts which leads more readily to testable hypotheses and empirical work.

Recent research synthesising public health theory and interventions has adopted a ‘logic model’ approach which elucidates the internal pathways of interventions (Baxter, Killoran, Kelly, & Goyder, 2010). As with other complex policy interventions, in implementing a health care contract, there are multi-factorial outcomes, and the causal chain between the agent and the outcome is neither short nor simple (Baxter et al., 2010). Understanding relationships between contextual factors, inputs, processes and outcomes is however useful to produce a ‘roadmap’ which illustrates influential relationships and components from inputs to outcomes. Conceptual models (logic models) are useful in providing a structure for exploring these complex relationships. Logic models originate from the field of programme evaluation and are typically diagrams or flow charts that convey relationships between contextual factors, inputs, processes and outcomes. In this paper we identify and map the complex set of concepts and relationships between concepts relevant to health care contracting. The aim of our review was to produce an aggregative synthesis using systematic review methods in order to map the internal pathways concerned with the implementation of health care contracts. The review was based on the research questions: what theories have been developed to understand how contracts work in the context of publicly funded health care; what major issues are involved and how do these influence the process and outcome both positively and negatively?

Method

An electronic search of the literature was undertaken using Web of Science, Scopus and Medline databases (search details online). The search was limited to journal articles published in English from 1980 onwards. Books or other types of reports were not included because if the theory were significant in the field, this would be cited and therefore identified in peer reviewed academic publications. We included papers concerned within the use of ‘managed competition’ (even though the approach was developed within a non-publicly funded health care system) where papers were either a) completely theoretical and not embedded in a particular health system context or b) a empirical paper set within a publicly funded health care context (either in the UK or beyond). Health care was defined as the delivery of patient care by a clinically qualified provider and hence articles concerned with the provision of ancillary services such as cleaning were excluded.

Articles where theory could not be identified were also excluded. In order to assess whether the article contained theory, Kerlinger's definition of a theory was applied: a theory is an interrelated set of constructs, definitions and propositions that presents a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relationships between variables with the purpose of explaining natural phenomena (Kerlinger, 1979). Three primary criteria were therefore set that had to be satisfied in order for the material to be identified as a theory. These widely recognised criteria were that a) constructs had to be identified, b) relationships among constructs had to be specified and c) these relationships had to be falsifiable (testable), (Doty & Glick, 1994). Although there is some debate as to whether typologies are theories or just simple classification systems, articles containing typologies were included provided these three features of a theory outlined were met.

The electronic search identified 1519 titles which were then screened independently by two researchers (SM, JG) for inclusion. Where there was disagreement, the abstract was obtained. The resulting 311 abstracts were then also screened by two researchers (RH, SM). Of the 131 papers remaining, a further 49 papers were excluded on reading (RH, SM, JG). The 82 included papers were then grouped according to macro-theory. For each paper constructs and relationships between constructs were identified. Papers outlining the same theory were grouped together using a thematic approach rather than a check-list, and papers organised according to a hierarchy of theory types (macro-theory and mid-level theory). In some cases mid-level theory could be associated with more than one macro theory, but was attributed to one only, for clarity. We have not also distinguished between mid-level theory and micro-theory because a range of levels of abstractions exists between the two which makes making reliable distinctions difficult. After cataloguing theories, concepts and relationships, a synthesis was produced by drawing of a logic model to summarise the main foci of interest and linkages between these concepts.

Results

We identified five macro-theories, and organised mid-level theory under these themes. Details of mid-level theory with sources are available in the supporting material online. In these online tables the 80 lower level concepts identified in each theory are outlined in bold print. The main features of each macro-theory are summarised briefly below.

Macro-theories of contracting

-

1)

Managed competition enhances efficiency, quality and consumer responsiveness

The theory of ‘managed’ competition refers to the employment of competition to promote efficiency and cost control, but with constraints employed by government or purchasers in such a way as to allow other health systems objectives to also be achieved such as quality, equity and responsiveness of services to consumers (Enthoven, 1985). A range of economic theories have been generated which outline the relationship between competition between providers and the cost, price and quality of health care services (Table 2 online).

-

2)

The Principal–Agent model

The Principal–Agent model describes the relationship between the principal who delegates an action to a single agent in a contract (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). The principal's problem is ensuring that the agent acts in the principal's interest, overcoming any different or conflicting interests. This is based on assumptions that agents have more information than principals and that human agents always rationally evaluate and exploit situations in order to maximise personal gain. Where one party exploits contract loopholes because of the limitation in the specificity of contract terms, this is termed opportunism (Williamson, 1975). A range of mid-level economic theories exist which identify which contract type is optimal to manage situations of asymmetric information and stochastic patient demand, in order to minimise the scope for opportunism (Table 3 online).

-

3)

Transaction Cost Economic theory

Transaction Cost Economics (TCE) argues that there are behavioural and informational factors as well as characteristics of the product which affect the level of transaction costs (Williamson, 1979). The issue central to TCE is whether it is more ‘efficient’ for transactions to proceed through the market or to be integrated within a hierarchical organisation (Ferlie, 1992). TCE identifies the circumstances where transaction costs may outweigh any cost savings generated from using an internal market approach (Table 4 online).

-

4)

Relational contracts

MacNeil (1974) distinguishes between classical, neoclassical and relational models of contracts in contract law. The classical model of the contract focuses on a single exchange between two parties. The contract is considered complete i.e. all possible eventualities are specified and there is full advance allocation of risk (Table 5 online). Since everything can be measured and recorded, opportunism is irrelevant. However, in many situations parties expect to do business again and therefore there is an interest in maintaining a relationship. A contract which is relatively flexible and which allows for unpredicted outcomes to be resolved by mutual agreement over the longer term is therefore more appropriate (the neoclassical model).

The concept of neo-classical contracts has been further developed using sociological theory to recognise the importance of social relations between the parties involved. How parties react during negotiation and contract performance is significantly influenced by the history of social relations between the parties and the social norms of trust and reciprocity (Ferlie, 1992). The relational model of the contract identifies social norms such as trust, solidarity and reciprocity embedded in the contractual relationship as one means of controlling opportunistic behaviour.

Whilst TCE suggests a one dimensional continuum of types of organisation form along which firms may place themselves with hierarchies (with centralised decision making and relatively little autonomy at lower levels) at one end and markets at another; relational theory offers a range of other possibilities such as strategic alliances and joint ventures (Ferlie & McGivern, 2003). Organisational forms described as network or clans formed through collaboration and inter-dependency, offer an alternative to the two extremes and are relatively common. Professions such as medicine display a strong network component which can shape the relational market and constrain opportunistic behaviour.

-

5)

Markets are institutionally as well as socially embedded

Social networks are increasingly considered important, not just at the micro-level, but also at an institutional level (Ferlie, 1994). Institutions such as the NHS and professions are thought to exert an influence on healthcare markets by acting as ‘congealed social networks’ (Ferlie, 1992); i.e. attitudes of the parties involved in the contract are influenced not merely by the relationships in which they are directly involved, but each party may have relationships with a wider network of people, as well as indirect relationships with professional bodies and the government (Table 6 online). All of this history and experience has an impact on providers' behaviour in the more immediate relationship. This perspective draws attention to the important influence on the contractual relationship of the wider institutional context in which an individual purchaser–provider relationship occurs (Ferlie, 1994). This differs from TCE and Principal–Agent approaches which both conceptualise the relationship between purchaser and provider as dyadic (Smith, 1996). Instead it recognises that a purchaser–provider relationship is not adequately conceptualised as a single Principal–Agent relationship, but is rather the product of a string of Principal–Agent relationships extending from the health care system into the political arena. This view of contracting is informed by political science, where the relationship between purchaser and provider is pictured as akin to international relations between states. Here the relationships are seen as ‘regimes’ which are based on ‘sets of principles, norms, rules and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge’ (Smith, 1996).

The logic model

In aggregating concepts we identified highlighted ‘contracts’ as the intervention input and ‘opportunism’ as an important intermediate outcome. The concepts shown in Fig. 1 are a higher level abstraction of 80 lower level concepts contained in the online Tables. Fig. 1 shows important distal factors such as the role of the state and the extent of societal trust in the provider institution which have an impact on the system. In Fig. 1 we have highlighted ten main concepts (represented as circles) and mapped links, intervening lower level concepts and internal pathways. In Fig. 1 intended (efficiency, quality, consumer responsiveness) and unintended (inequity, market segmentation) outcomes of contracting are depicted as cloud shapes.

Fig. 1.

Determinants of health care contracting outcomes in the NHS dental practice context.

Discussion

The work outlined here is primarily integrative, aiming to extend our understanding of the complex relationships between concepts involved in health care contracting. The directionality of some of the causal relationships between concepts is tentative and further work is needed to establish them. We recognise that the literature review is not exhaustive, rather that it follows the principles of realist analysis in that a point of theoretical saturation is reached in literature searching where further material does not add substantially to findings (Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, & Walshe, 2005).

The logic map (Fig. 1) lays bare elements that are key to influencing dental practice contracts. In Fig. 1 we suggest (in the shaded symbols) contextual factors which are particularly pertinent to dental practice, and distinguish dental from medical practices. Some of these factors represent the type of the market (e.g. whether there are sufficient numbers of providers in the area to give rise to competition - departure of GDPs to the private sector has left some areas of the UK under-served by public sector providers), and the likelihood that contracts will be contestable. An important characteristic of dental markets is that they are highly asset specific: with a significant investment of premises and equipment necessary for new entrants to the market and this raises barriers to entry for smaller enterprises. The usual market response to asset specificity is the negotiation of longer term contracts that include risk-sharing arrangements between both purchaser and provider (Howden-Chapman & Ashton, 1994) - a mechanism which has never been used in the NHS dental context. Theory however suggests that ownership is central to the normal workings of markets and purchaser–provider sharing of capital assets acts as a powerful motivator for agents (Roberts, 1993). Indeed, this is the model used in general medical practice, where a rent reimbursement scheme for GMPs owning medical practice premises (representing transaction specific assets) is in place, with (up until 2013) this being tied to conditions restricting the balance of NHS/private work carried out in that practice. For practitioners not owning premises, purchasers effectively loan capital assets, although the full implications of this type of ownership are far from clear (Roberts, 1993).

The model also identifies the role of the state in influencing outcomes of contracting. The willingness of the state to allow providers to fail in a competitive market may vary (they may be more willing to let dental services fail than medical services because dental services may be rated as a lower priority than many other parts of the health care system). It also identifies the role of the media and the way the profession is portrayed, as a distal factor influencing the extent to which practitioners and their profession are trusted in wider society. The influence of the media can also impact directly on political choices made by the state concerning the management of the market via contracts.

Contract theory literature also tells us that using patients to seek out services on the basis of quality can be a contract design tool which has the potential to restrain opportunism. In theory consumers are more willing to select dental services on the basis of quality than medical services because consumers tend to be risk averse when their condition is life-threatening. Since building practice ‘goodwill’ has historically been integral to NHS dental practice because of financial responsibilities concerned with ownership, being orientated towards consumer interests has always been part of the culture of the organisation (for more detail see online Appendix). However since consumer demand can conflict with what constitutes need, defining quality as perceived by patients in a publicly funded system subject to financial constraints, can be difficult. Because practitioners have a more immediate relationship with patient demand than do purchasers who attempt to control the costs through contract rules, practitioners may attempt to control resources indirectly through ‘gaming’ the system. Morreim (1991) suggests that practitioners may be especially inclined to game the system where contract rules seriously under-serve patients' needs. Thus Rees Jones (1995) portrays health care contracting as a bargaining process which is formalised at a micro-level, acting as a mechanism for clarifying tensions between patients' needs and providers' vested interests.

Rees Jones (1995) further suggests the micro-level bargaining concerned with interpreting contract rules in the clinical setting is set in a wider context of policy making which is a ‘network or bargaining community’ between the government and the medical profession. Our logic model recognises these wider influences as mediated by personal, professional and political networks, although the mechanics of whether and how micro-level bargaining is related to macro-level bargaining is under-explored. Oliver (1991) describes a typology of active organisational resistance to institutional change which ranges from passive conformity, through compromise (which includes balancing tactics accommodating multiple constituent demands), to open challenge and defiance. ‘Gaming’ may represent a form of compromise. Oliver's portrayal of a strategic choice between conformity and resistance to institutional pressures may help us to understand why considerable variation between dentists is found in their response to financial incentives. There is currently an assumption that this is mainly because of differences in the intrinsic motivation of practitioners (Chalkley, Tilley, Young, Bonetti, & Clarkson, 2010).

Social capital can be defined as ‘those expectations for action that affect economic goals and goal-seeking behaviour of its members’ (Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993, p. 1323). This infers that a member of a collectivity orients his/her behaviour to the ‘web of social networks of the entire community’ (p. 1325). Personal, professional and political networks can therefore shape the way individual providers respond. Chan (1997) identifies two mechanisms whereby behaviour is shaped by networks: firstly in the transmission of network norms and culture via the interconnectedness of mutual contacts (which she suggests has an indirect effect); and secondly in the diffusion of bad reputation arising from dealings between parties with common ties where one party defects (a more direct effect). Particular to the GDS contracting context is the history of relations (at times difficult) between the UK dental profession and government. What we do not know is how this history has influenced professional network norms of behaviour in relation to contract rules.

Thus as we look to the future, and weigh the prospects of the latest version of the NHS dental contract due to be implemented in 2015, being more ‘successful’ than the various iterations that have gone before, theory suggests that we should not just focus on the relevant merits of various contract currencies (fee-per-item, capitation and the like), but on more general issues concerned with institutional change, information asymmetry, mutual goals, shared risk etc. In other words, contracting should be viewed as far from merely a technical task, but as a complex intervention influenced by a system of inter-related social networks, organisational forms, labour markets, political policies and institutions (Bennet & Ferlie, 1996). The online Appendix provides a fuller analysis of factors identified in the theory review along with implications for future policy in this area.

Department of Health disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme (project number 09/1801/1055).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Baxter S., Killoran A., Kelly M.P., Goyder E. Synthesizing diverse evidence: the use of primary qualitative data analysis methods and logics models in public health reviews. Public Health. 2010;124:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet C., Ferlie E. Contracting in theory and practice: some evidence from the NHS. Public Administration. 1996;74:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chalkley M., Tilley C., Young L., Bonetti D., Clarkson J. Incentives for dentists in public service: evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Public Administration. 2010;20(Suppl. 2):1207–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. Some theoretical propositions pertaining to the context of trust. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 1997;5:227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Doty D.H., Glick W.H. Typologies as a unique form of theory building: toward improved understanding and modelling. Academy of Management Review. 1994;19:230–251. [Google Scholar]

- Enthoven A. Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; London: 1985. Reflections on the management of the National Health Service. Occasional Paper 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie E. The creation and evolution of quasi markets in the public sector - a problem for strategic management. Strategic Management Journal. 1992;13:79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie E. The creation and evolution of quasi-markets in the public sector: early indications from the National Health Service. Policy and Politics. 1994;22:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie E., McGivern G. Imperial College; London: 2003. Relationships between health care organisations: A critical overview of the literature and the research agenda. Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery & Organisation by the CPSO. [Google Scholar]

- Harris R., Holt R. Interacting logics in general dental practice. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;94:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons Health Select Committee . HMSO; London: 2008. Dental services. Fifth report of Session 2007–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Howden-Chapman P., Ashton T. Shopping for health: purchasing health services through contracts. Health Policy. 1994;29:61–83. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(94)90007-8. (1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M., Meckling W. The theory of the firm: managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. 1976;3:305–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger F.M. Holt, Winehart and Winston, Inc; Philadelphia: 1979. Behavioural research: A conceptual approach. [Google Scholar]

- Light D.W. Managed competition, governmentality and institutional response in the United Kingdom. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52:1167–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil I. The many futures of contracts. Southern California Law Review. 1974;47:691–816. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R. Market reforms in English primary medical care: medicine, habitus and the public sphere. Sociology of Health and IIlness. 2009;31:659–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morreim E.H. Dodging the rules, ruling the dodgers. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1991;151:443–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C. Strategic responses to institutional pressures. Academy of Management Review. 1991;16:145–179. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R., Greenhalgh T., Harvey G., Walshe K. Realist review – a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research Policy. 2005;10:21–25. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock A.M., Price D., Viebrook E., Miller E., Watt G. The market in primary care. British Medical Journal. 2007;335:475–477. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39303.425359.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A., Sensenbrenner J. Embeddedness and immigration: notes on the social determinants of economic action. American Journal of Sociology. 1993;98:1320–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Rees Jones I. Health care need and contracts for health services. Health Care Analysis. 1995;3:91–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02198209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J.A. Managing markets. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1993;15:305–310. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.R. Transforming public services: contracting for social and health services in the US. Public Administration. 1996;74(1):113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Waring J., Bishop B. McDonaldization or commercial re-stratification: corporatization and the multimodal organisation of English doctors. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;82:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson O.E. Free Press; New York: 1975. Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and anti-trust implications. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson O.E. Transaction cost economics: the governance of contractual relations. The Journal of Law and Economics. 1979;22:233–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wynes D.K., Baines D.L. Income-based incentives in UK general practice. Health Policy. 1998;43:15–31. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(97)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.