Abstract

Background

Prostaglandins (PGs), lipid autacoids derived from arachidonic acid, play a pivotal role during inflammation. PGD2 synthase is abundantly expressed in heart tissue and PGD2 has recently been found to induce cardiomyocyte apoptosis. PGD2 is an unstable prostanoid metabolite; therefore the objective of the present study was to elucidate whether its final dehydration product, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2, present at high levels in ischemic myocardium) might cause cardiomyocyte damage.

Methods and results

Using specific (ant)agonists we show that 15d-PGJ2 induced formation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and phosphorylation of p38 and p42/44 MAPKs via the PGD2 receptor DP2 (but not DP1 or PPARγ) in the murine atrial cardiomyocyte HL-1 cell line. Activation of the DP2-ROS-MAPK axis by 15d-PGJ2 enhanced transcription and translation of TNFα and induced apoptosis in HL-1 cardiomyocytes. Silencing of TNFα significantly attenuated the extrinsic (caspase-8) and intrinsic apoptotic pathways (bax and caspase-9), caspase-3 activation and downstream PARP cleavage and γH2AX activation. The apoptotic machinery was unaffected by intracellular calcium, transcription factor NF-κB and its downstream target p53. Of note, 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 (lacking the electrophilic carbon atom in the cyclopentenone ring) did not activate cellular responses. Selected experiments performed in primary murine cardiomyocytes confirmed data obtained in HL-1 cells namely that the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic cascades are activated via DP2/MAPK/TNFα signaling.

Conclusions

We conclude that the reactive α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group of 15d-PGJ2 is responsible for the pronounced upregulation of TNFα promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis. We propose that inhibition of DP2 receptors could provide a possibility to modulate 15d-PGJ2-induced myocardial injury.

Keywords: Cardiomyocytes, TNFα, 15d-PGJ2, Apoptosis, PGD2 receptor

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are more prevalent worldwide compared to other diseases, amongst which myocardial ischemia caused by coronary blockage is by far the most frequent cause of mortality [1,2]. Imbalanced oxygen demand and supply to cardiomyocytes during coronary artery disease (CAD) activates cell death cascades and promotes myocardial infarction (MI) [3]. Advances in treatment based on currently available targets have failed to change the status of CAD/MI and therefore we await novel strides in fundamental understanding through which we might be able to manipulate progression of CAD and MI.

Changes in fatty acid compositions of myocardial lipids were found to be associated with CAD and MI [2]. Elevated phospholipase A2 (PLA2) mass and activity, as reported in patients with myocardial ischemia [4], lead to accumulation of unesterified arachidonic acid (AA) from phospholipids in the heart [5]. As a consequence, increased tissue levels of prostaglandins (PGs) e.g., PGI2, PGE2, and its isomer PGD2, generated via cyclooxygenase (COX)-mediated conversion of AA have been observed in the ischemic myocardium [6]. However, PGD2 is degraded in vitro and in vivo to a variety of metabolites, the majority of which were thought, until recently, to be physiologically inactive [7]. PGD2 is either metabolized enzymatically to 13,14-dihydro-15-keto PGD2 [7] (for chemical structures, see Supplement Fig. I) or readily dehydrated into J series prostanoids characterized by the presence of an α,β-unsaturated ketone in the cyclopentenone ring. Particularly 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2, Supplement Fig. I), the final dehydration product of PGD2 has been shown to have broad effects on various cellular systems [8,9]. 15d-PGJ2 is a potent endogenous ligand for the peroxisome proliferator-activated-receptor γ (PPARγ), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-dependent transcription factors (for review see [10,11]). However, recent findings confirm that 15d-PGJ2 exerts a variety of cellular responses via PPARγ-independent mechanisms, e.g. activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [12,13], modulation of Akt and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) [14,15], induction of oxidative stress [16], expression of cytokines [17], promotion of apoptosis [18,19], up-regulation of antioxidant response genes [20,21] and modulation of COX-2 [22].

Depending on disease etiology, PGD2 may exert pro- as well as anti-inflammatory effects in different biological systems [23] via two distinct G-protein coupled receptors, (i) the D-type prostanoid receptor (DP1) and (ii) the chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 cells (CRTH2, also named DP2). Although DP1-mediated activities have also been suggested [24], PGD2-derived metabolites seem to preferentially interact with DP2 [7].

Abundant DP2 mRNA expression has been found in human heart [25] and pronounced staining for DP1 and DP2 protein has been found in murine cardiomyocytes [6]. Qiu and colleagues [6] have recently reported that PGD2 (but not PGE2 or PGI2) favors cardiomyocyte death during MI. As high 15d-PGJ2 levels were detected in myocardial tissues subsequent to ischemia–reperfusion injury [26], this bona fide PGD2 metabolite is likely to act as the leading cause for cardiomyocyte death during CAD.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore whether 15d-PGJ2, formed in vivo during resolving inflammation [24], may interact with candidate receptors (DP1, DP2 and/or PPARγ) present on cardiomyocytes. Next we were interested in receptor-dependent or -independent activation of signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes. As 15d-PGJ2 may modulate cytokine production [17], expression and involvement of candidate cytokines that promote inflammation and/or apoptosis were studied. Finally, we sought to clarify structure–activity relationships of 15d-PGJ2 analogs-mediated effects in cardiomyocytes.

2. Materials and methods

A detailed Materials and methods section on cell culture [27], isolation of primary murine cardiomyocytes [28], incubation protocols, Western blot analysis [22,29], RNA isolation and real time RT-PCR (qPCR) [30], TNFα RNA interference and silencing [22], reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurements [31], cell viability assay [31], TNFα ELISA experiments and statistics is available in the online Supplement.

3. Results

3.1. 15d-PGJ2 promotes MAPK activation in cardiomyocytes via intracellular redox imbalance

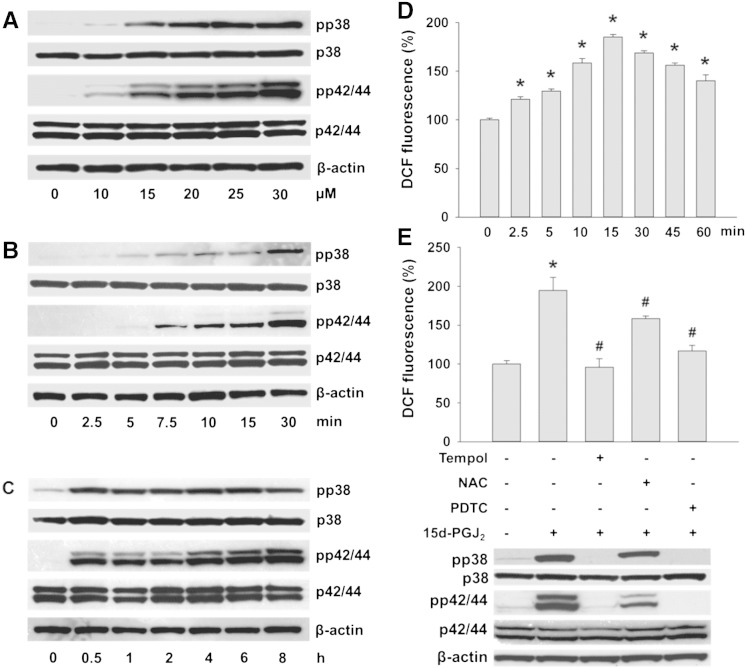

Treatment of HL-1 cells with increasing 15d-PGJ2 concentrations induced phosphorylation of p38 and p42/44 MAPK (Fig. 1A). As pronounced MAPK activation was observed at 15 μM 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 1A), this concentration was chosen for further experiments. Fig. 1B/C show time-dependent activation of both MAPKs by 15d-PGJ2. Phosphorylation was detectable after 5 (pp38 MAPK) and 7.5 min (pp42/44 MAPK). MAPK phosphorylation reached maximal levels after 30 min that persisted up to 8 h. Densitometric and statistical evaluations of immunoreactive (non)phosphorylated MAPK signals (Fig. 1A–C) and normalization to β-actin is shown in the Supplement (Fig. II and Fig. IIIA/B). Total MAPKs and β-actin levels were unaffected by 15d-PGJ2.

Fig. 1.

15d-PGJ2 promotes MAPK activation in cardiomyocytes via intracellular redox balance.

(A) HL-1 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 for 1 h to follow pp38 and pp42/44 MAPK expression by Western blot. Cells were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) for indicated time periods to follow (B/C) pp38 and pp42/44 MAPK expression and (D) ROS generation by DCF fluorescence. Cells were incubated with ROS scavengers (Tempol [1 mM], NAC [5 mM] or PDTC [1 mM]) for 30 min prior to 15d-PGJ2 treatments (15 μM) for 1 h to follow (E, upper panel) ROS generation and (E, lower panel) pp38 and pp42/44 MAPK expression. For Western blot analysis protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoreactive bands were visualized using specific primary and secondary antibodies. For normalization, membranes were stripped and probed with primary antibodies against β-actin as well as total p38 and p42/44 MAPK. One representative blot (A–C and E) out of three is shown. (D) For detection of intracellular ROS levels cells were incubated with carboxy-H2DCFDA (10 μM) for 30 min after treatment with 15d-PGJ2. DCF fluorescence levels of vehicle (0.1% DMSO)-treated cells were set 100% and values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). * p ≤ 0.05 vs. untreated.

Cellular activation by 15d-PGJ2 may induce ROS generation [22,32]. To clarify whether the formation of intracellular ROS in cardiomyocytes is affected by 15d-PGJ2 the peroxidase-sensitive probe DCFDA was used. Upon stimulation significantly increased DCF fluorescence was observed acutely after 2.5 min (Fig. 1D). In response to 15d-PGJ2 ROS levels reached a maximum at 15 min and were 1.4-fold above baseline levels after 60 min (Fig. 1D).

Next, we assessed the effects of antioxidants on 15d-PGJ2-treated cardiomyocytes. Fig. 1E (upper panel) shows that the antioxidant PDTC and Tempol (a cell-permeable nitroxide and superoxide anion scavenger) blunted 15d-PGJ2-induced ROS formation efficiently while NAC (also preferentially reacting with superoxide anions) was less effective. To test whether the time-dependent increase in ROS formation (Fig. 1D) precedes MAPK activation, cardiomyocytes were incubated with ROS scavengers prior to 15d-PGJ2 treatments. Tempol and PDTC completely blunted p38 and p42/44 MAPK phosphorylation (Fig. 1E, lower panel) while NAC was again less effective; phosphorylation of MAPKs was impaired by 40% (p38 MAPK) and 70% (p42/44 MAPK) (for densitometric evaluations of Western blots see Supplement Fig. IIIC/D). These findings suggest that 15d-PGJ2-mediated ROS activation is upstream of p38 and p42/44 MAPK phosphorylation.

3.2. DP2 mediates ROS production and MAPK activation in cardiomyocytes in response to 15d-PGJ2

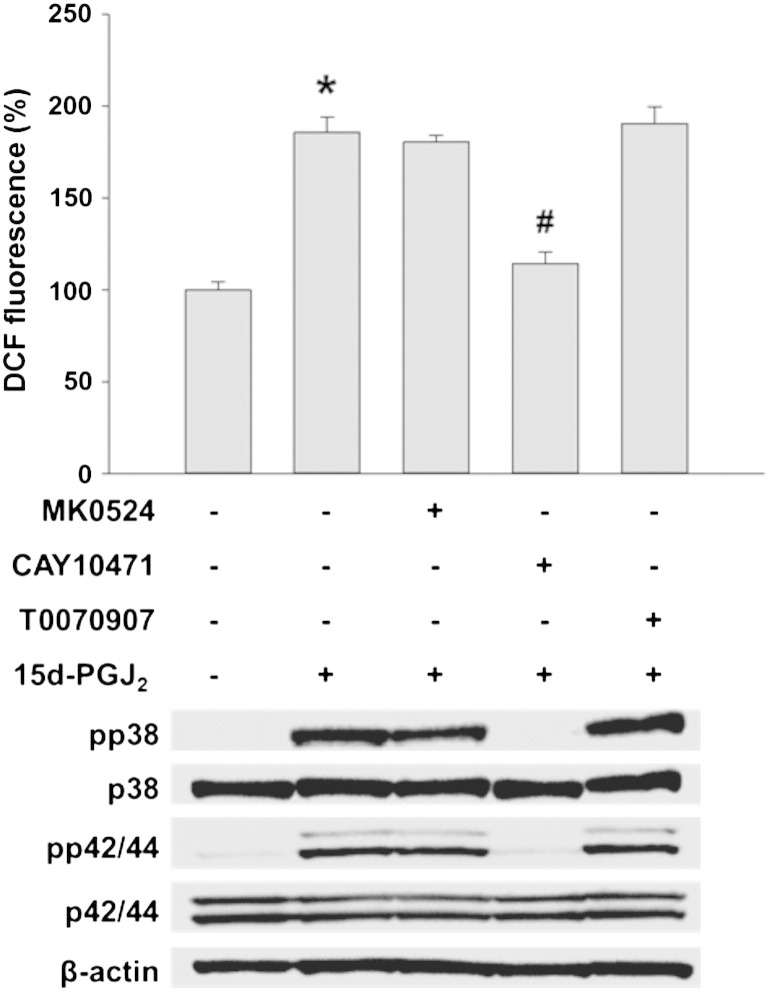

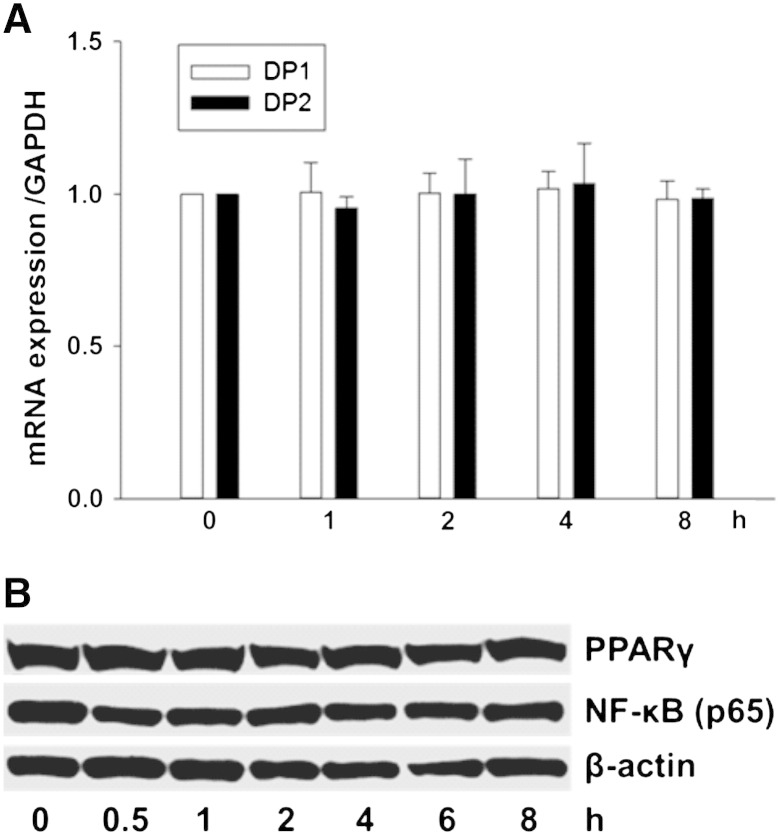

15d-PGJ2-mediated cellular activation may involve receptor-independent and -dependent pathways [11]. To test involvement of candidate receptors for ROS production and MAPK activation, HL-1 cells were incubated with three different receptor antagonists/inhibitors. Fig. 2 shows that CAY10471 (DP2 antagonist) but not MK0524 (DP1 antagonist) or T0070907 (PPARγ inhibitor) reversed 15d-PGJ2-induced ROS production (upper panel) and MAPK activation (lower panel) in cardiomyocytes almost to baseline levels (densitometric evaluations and statistical analyses of Western blots are shown in Supplement Fig. IVA/B). To reveal whether 15d-PGJ2 impacts on DP2 transcription, cells were stimulated with 15d-PGJ2 up to 8 h prior to RNA isolation. These experiments revealed that 15d-PGJ2 does not affect DP2 transcription (Fig. 3A; DP1 receptor expression was analyzed in parallel) and that ROS formation and MAPK activation are downstream events of 15d-PGJ2-mediated DP2 engagement. Furthermore, expression of PPARγ as well as its downstream target transcription factor NF-κB were not altered by 15d-PGJ2 treatment (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 2.

DP2 mediates ROS production and MAPK activation in cardiomyocytes in response to 15d-PGJ2.

HL-1 cells were incubated with MK0524 (100 nM), CAY10471 (1 μM) or T0070907 (20 μM) for 30 min prior to 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) treatments for 15 min to follow ROS levels by DCF fluorescence (upper panel) and 1 h to follow pp38 and pp42/44 MAPK expression (lower panel). For detection of intracellular ROS levels cells were incubated with carboxy-H2DCFDA (10 μM) for 30 min after treatment with 15d-PGJ2. DCF fluorescence levels of vehicle (0.1% DMSO)-treated cells were set 100% and values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). * p ≤ 0.05 vs. untreated and # p ≤ 0.05 vs. 15d-PGJ2 treated. For Western blot analysis protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoreactive bands were visualized using specific primary and secondary antibodies. For normalization, membranes were stripped and probed with primary antibodies against β-actin as well as total p38 and p42/44 MAPK. One representative blot out of three is shown.

Fig. 3.

Expression of PG receptors DP1, DP2 and PPARγ.

HL-1 cells were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) for indicated time periods to follow (A) DP1 and DP2 mRNA expression using qPCR as well as (B) PPARγ and NF-κB protein expression using Western blot. For mRNA expression cells were lysed, RNA was isolated and qPCR was performed using specific primers. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). For Western blot analysis protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoreactive bands were visualized using specific primary and secondary antibodies. For normalization, membranes were stripped and probed with primary antibodies against β-actin. One representative blot (B) out of three is shown.

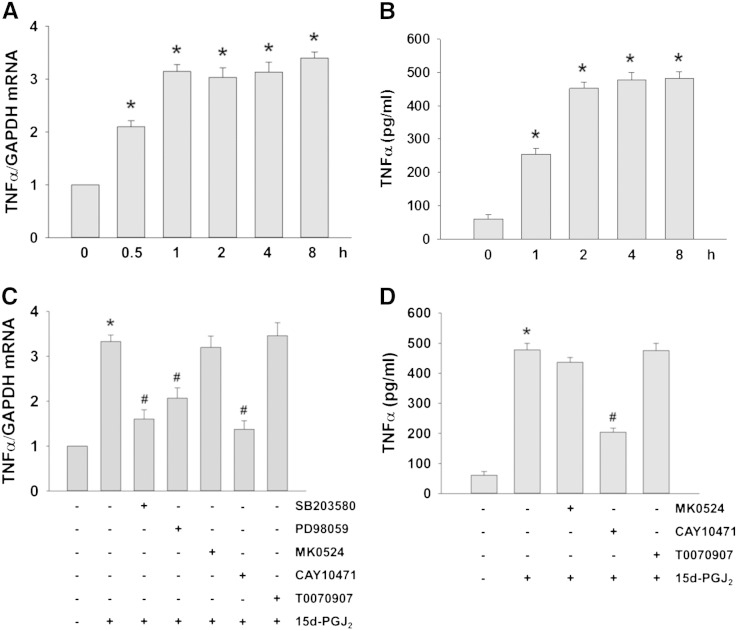

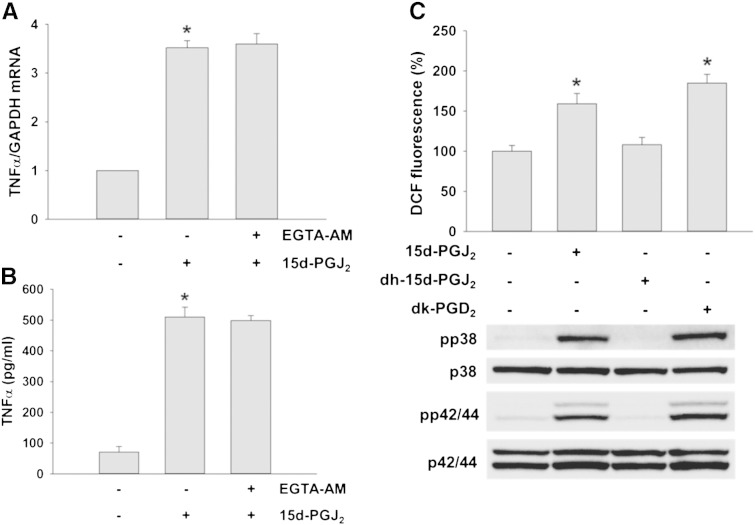

3.3. The DP2-ROS-MAPK axis increases TNFα transcription and translation in 15d-PGJ2-stimulated cardiomyocytes

DP2 plays a central role in pathogenic inflammation [33] and 15d-PGJ2 may promote induction of pro-inflammatory proteins under certain conditions [11]. We observed that mRNA levels of cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1α, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10) were not altered by 15d-PGJ2 treatments of HL-1 cells (data not shown), while TNFα levels were highly upregulated on mRNA and protein levels by 3- and 6-fold (Fig. 4A and B), respectively.

Fig. 4.

DP2-ROS-MAPK signaling increases TNFα transcription and translation in 15d-PGJ2-stimulated cardiomyocytes.

HL-1 cells were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) for indicated time periods to follow (A) TNFα mRNA expression by qPCR and (B) TNFα protein concentrations in the cell culture medium by ELISA. Cells were incubated with SB203580 (10 μM), PD98059 (25 μM), MK0524 (100 nM), CAY10471 (1 μM) or T0070907 (20 μM) for 30 min prior to 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) treatment for 4 h to follow (C) TNFα mRNA expression and (D) TNFα protein concentrations in the cell culture medium. After treatment with 15d-PGJ2 the cell culture medium was removed and cells were lysed to isolate RNA for qPCR analysis using specific primers (A/C) (n = 6). The cell culture medium was used to quantitate TNFα concentrations using ELISA (B/D) (n = 3). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p ≤ 0.05 vs. untreated and # p ≤ 0.05 vs. 15d-PGJ2.

Next, we aimed to elucidate intracellular signaling cascades that mediate this response. Both, SB203580 and PD98059 (inhibitors of pp38 MAPK and p42/44 MAPK kinase) significantly blocked TNFα transcription in response to 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 4C). Of note, only CAY10471 (DP2 antagonist) but not MK0524 (DP1 antagonist) or T0070907 (PPARγ antagonist) reduced TNFα mRNA and protein expression levels in response to 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 4C and D). Supplement Fig. V supports specificity and efficacy of the respective inhibitors to block respective MAPK pathways.

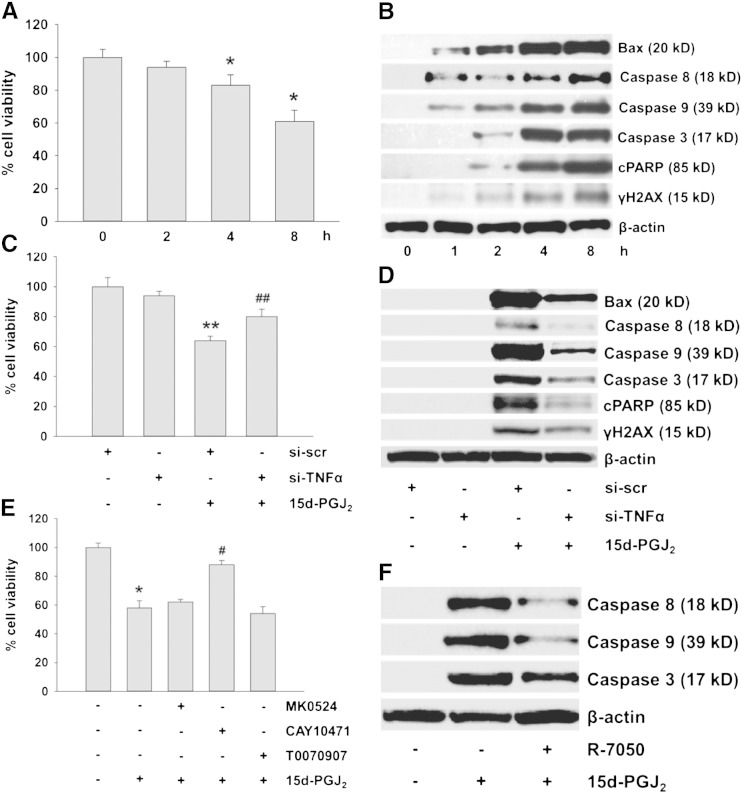

3.4. 15d-PGJ2-mediated TNFα induces the apoptotic machinery in cardiomyocytes

TNFα has recently been shown to induce cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo [34,35]. This was now investigated in HL-1 cells. 15d-PGJ2 treatment (15 μM) reduced cell viability in a time-dependent manner up to 35% after 8 h (Fig. 5A). Fig. 5B shows activation of the extrinsic (caspase-8) and intrinsic apoptotic pathways (bax and caspase-9) as well as induction of caspase-3, the convergence point of both pathways. Furthermore, downstream events of caspase-3 activation, namely PARP cleavage (a hallmark of apoptosis) and activation of γH2AX (an indicator of DNA damage) became apparent (Fig. 5B; densitometric evaluations and statistical analyses of immunoreactive bands are shown in Supplement Fig. VIA/B).

Fig. 5.

15d-PGJ2-induced TNFα activates the apoptotic machinery in cardiomyocytes.

HL-1 cells were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) for indicated time periods to measure (A) cell viability using MTT assay and to follow (B) apoptotic markers by Western blot. Alternatively, cells were transfected with scrambled negative control siRNA (si-scr, 40 nM) or siRNA against TNFα (si-TNFα, 40 nM) for 6 h and grown for 24 h followed by 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) treatment for 4 h to follow (C) cell viability and (D) apoptotic markers. Cells were incubated with (E) MK0524 (100 nM), CAY10471 (1 μM), T0070907 (20 μM) or (F) R-7050 (30 μM) for 30 min prior to 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) treatments for 4 h to follow (E) cell viability and (F) markers of apoptosis. For Western blot analysis protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoreactive bands were visualized using specific primary and secondary antibodies. For normalization, membranes were stripped and probed with primary antibody against β-actin. One representative blot out of three (B, D, and F) is shown. Only cleaved (but not pro-forms) of PARP (cPARP), caspase-3, -8 and -9 are shown. Cell viability was measured following incubating cells with MTT (0.5 mg/ml) for 30 min after treatment with 15d-PGJ2. Optical density levels of vehicle (0.1% DMSO)-treated cells were set 100% and values are expressed as mean ± SEM (A, C and E) (n = 6). * p ≤ 0.05 vs. untreated, # p ≤ 0.05 vs. 15d-PGJ2, ** p ≤ 0.05 vs. si-scr and ## p ≤ 0.05 vs. si-scr + 15d-PGJ2.

As a 4 h treatment of cardiomyocytes with 15d-PGJ2 led to pronounced activation of the apoptotic machinery (Fig. 5B, Supplement Fig. VIA/B), this time point was chosen for further experiments. To confirm TNFα as an inducer of cell death, HL-1 cells were transfected with TNFα-siRNA prior to 15d-PGJ2 treatments (silencing efficacy is shown in Supplement Fig. VII). Silencing of TNFα restored cell viability (Fig. 5C) and reduced expression of apoptotic markers (Fig. 5D; densitometric and statistical evaluations of Western blots are shown in Supplement Fig. VIC/D).

To confirm that DP2 is the candidate receptor for 15d-PGJ2-dependent TNFα synthesis and apoptosis, cardiomyocytes were pre-treated with specific antagonists. Only the DP2 inhibitor CAY10471 (but not MK0524 or T0070907) effectively restored cell viability of 15d-PGJ2-treated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5E). Summarizing these observations (Figs. 4 and 5), we conclude that 15d-PGJ2 induces cardiomyocyte death pathways through the involvement of the DP2/TNFα axis.

Next, we studied TNF receptor involvement in 15d-PGJ2-mediated apoptosis. Pharmacological antagonism of TNF receptor 1 and 2 (R-7050, [35]) inhibited the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways (Fig. 5F; densitometric and statistical evaluations of Western blots are shown in Supplement Fig. VIII).

3.5. 15d-PGJ2-induced signaling is calcium-independent but mediated via its cyclopentenone ring

The interaction of 15d-PGJ2 with DP2 could promote the pro-inflammatory cascade via alterations in intracellular calcium concentrations [11]. To reveal whether this route might be operative in HL-1 cells, the cell permeable Ca2 + chelating agent EGTA-AM was used. Preincubation of cardiomyocytes with EGTA-AM did not affect 15d-PGJ2-stimulated TNFα synthesis on mRNA and protein levels suggesting that the observed pro-inflammatory effect is independent of intracellular calcium homeostasis (Fig. 6A and B).

Fig. 6.

15d-PGJ2-induced signaling is calcium-independent and mediated via its cyclopentenone ring.

HL-1 cells were incubated with EGTA-AM (50 μM) for 30 min prior to 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM) treatment for 4 h to follow (A) intracellular TNFα mRNA expression and (B) TNFα protein concentrations in the cell supernatant. After treatment with 15d-PGJ2 the cell culture medium was removed and cells were lysed to isolate RNA for qPCR analysis (A, n = 6) using specific primers. The cell culture medium was used for TNFα quantification by ELISA (B, n = 3). Alternatively, cells were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 (15 μM), 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 (dh-15d-PGJ2, 15 μM) or 13,14-dihydro-15-keto PGD2 (dk-PGD2, 1 μM) for 1 h to follow (C, upper panel) ROS levels by DCF fluorescence and (C, lower panel) pp38 and pp42/44 MAPK expression. For Western blot analysis protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoreactive bands were visualized using specific primary and secondary antibodies. For normalization, membranes were stripped and probed with primary antibodies against total p38 and p42/44 MAPK. One representative blot (C, lower panel) out of three is shown. * p ≤ 0.05 vs. untreated.

To get insight into the structural requirements that mediate increased ROS production in cardiomyocytes, two chemical analogs of 15d-PGJ2 were tested. 9,10-Dihydro-15d-PGJ2 lacks the reactive α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group and an electrophilic carbon atom in the cyclopentenone system (Supplement Fig. I). 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto PGD2 further lacks the electrophilic carbon atom and the aliphatic double bond adjacent to the cyclopentenone system (Supplement Fig. I). Compared to 15d-PGJ2, treatment with 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 did alter neither DCF fluorescence (Fig. 6C, upper panel) nor phosphorylation of MAPKs (Fig. 6C, lower panel). In a parallel approach, cardiomyocytes were treated with the DP2 agonist 13,14-dihydro-15-keto PGD2. These data (Fig. 6C) demonstrate that DP2-mediated ROS formation and activation of MAPK is due either to the cyclopentenone ring present in 15d-PGJ2 or to a hydroxycyclopentanone system present in 13,14-dihydro-15-keto PGD2. Densitometric evaluations and statistical analyses of Western blots are shown in Supplement Fig. IX.

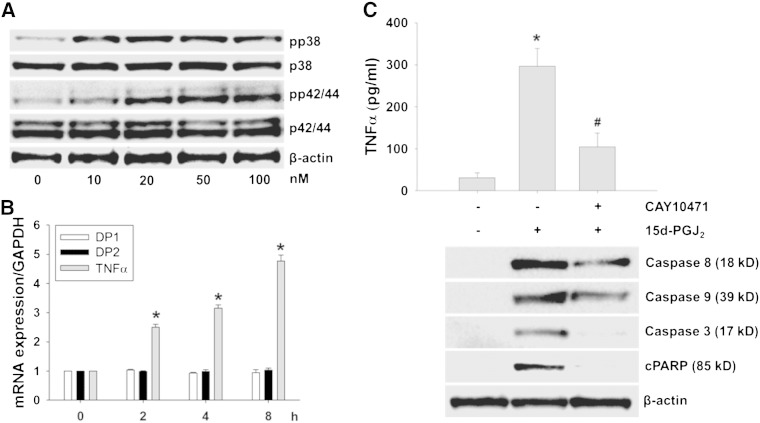

3.6. 15d-PGJ2 induces apoptosis in primary murine cardiomyocytes via DP2/MAPK/TNFα signaling

To confirm our findings obtained in HL-1 cells in a more physiological setting, primary murine cardiomyocytes were isolated and selected experiments were performed. Treatment of primary cardiomyocytes with increasing 15d-PGJ2 concentrations induced phosphorylation of p38 and p42/44 MAPK (Fig. 7A) at much lower agonist concentrations (10–100 nM) when compared to HL-1 cells (15 μM, Fig. 1A). As pronounced MAPK activation was observed at 50 nM 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 7A), this concentration was chosen for further experiments. Fig. 7B shows that 15d-PGJ2 does not affect DP2 transcription (DP1 receptor expression was analyzed in parallel) while an increase of TNFα mRNA was observed already at 2 h post treatment. After 8 h, TNFα transcription was increased by approx. 5-fold. Under these conditions (8 h) TNFα protein concentrations released by primary cardiomyocytes increased to approx. 300 pg/ml (vs. 35 pg/ml under basal levels). Preincubation of cardiomyocytes with the DP2 inhibitor CAY10471 reduced TNFα levels by 62% (to approx. 105 pg/ml) (Fig. 7C, upper panel). As TNFα has been shown to induce apoptosis in HL-1 cells (Fig. 5) this was now tested in primary cardiomyocytes. Fig. 7C (lower panel) shows 15d-PGJ2-mediated activation of the extrinsic (caspase-8) and intrinsic apoptotic pathways (caspase-9), induction of caspase-3 (the convergence point of both pathways), and PARP cleavage. Pretreatment of primary cardiomyocytes with CAY10471 partially inhibited caspase-8 and -9 (by approx. 50%) and caspase-3 and PARP cleavage completely (Fig. 7C, lower panel).

Fig. 7.

15d-PGJ2 induces apoptotic pathways in primary murine cardiomyocytes.

(A) Cardiomyocytes were treated with indicated concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 for 1 h to follow pp38 and pp42/44 MAPK expression by Western blot. (B/C) Primary cardiomyocytes were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 (50 nM) (B) for indicated time periods to follow TNFα mRNA expression by qPCR, or (C) for 8 h to follow TNFα protein concentrations in the cell culture medium (upper panel) and markers of apoptosis (lower panel). For Western blot analysis protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoreactive bands were visualized using specific primary and secondary antibodies. For normalization, membranes were stripped and probed with a primary antibody against β-actin. One representative blot out of two (A and C, lower panel) is shown. Only cleaved (but not pro-forms) of PARP (cPARP), caspase-3, -8 and -9 are shown. After treatment with 15d-PGJ2 the cell culture medium was removed and cells were lysed to isolate RNA for qPCR analysis using specific primers (B) (n = 3). The cell culture medium was used for quantitation of TNFα by ELISA (C, upper panel) (n = 3). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p ≤ 0.05 vs. untreated and # p ≤ 0.05 vs. 15d-PGJ2.

4. Discussion

The development of sarcolemmal membrane injury and the associated loss of cell viability observed during myocardial injury are causally related to progressive phospholipid degradation [36]. The net loss of phosphatidylcholine during MI correlates with PLA2-mediated generation of free AA that can directly induce apoptosis in cardiomyocytes [37–39] or is fuelled into PG biosynthesis. Clearly, the majority of biological effects mediated by AA can be attributed to COX-mediated formation of PGH2 and subsequent isomerization to primary active PG metabolites by distinct PG synthases. In vivo studies demonstrated that in cardiomyocytes the PLA2/COX/PGD2 synthase cascade is responsible for PGD2 formation [40] from its precursor PGH2. Expression analysis revealed that PGD2 synthase is abundant in heart tissue where immunoreactivity is localized to atrial and ventricular myocytes [41].

Lipid mediators can be either anti- or pro-inflammatory depending on disease etiology, cell type and eicosanoid receptor expression [24]. Not surprisingly, there is also some controversy concerning the outcome of PGD2 signaling in the heart: While Qiu and coworkers [6] have reported that PGD2 induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis during MI, another group [40] suggested that glucocorticoid induction of PGD2 synthase is cardioprotective. This could be due to different signaling cascades or altered downstream metabolism of PGD2.

Like other prostanoids, PGD2 is rapidly converted into various metabolites in vivo [24,42]; some of the species transported in the circulation produce effects at cells/organs distant from the site of PGD2 synthesis [43]. Hirai and colleagues [43] suggested that PGD2 metabolites such as 13,14-dihydro-15-keto PGD2 and 15d-PGJ2 might play important physiological roles that are mediated via DP2. To clarify effects of 15d-PGJ2 on HL-1 cell and primary cardiomyocyte function in vitro we have used pharmacological and genetic tools. Results from the present study suggest that 15d-PGJ2, via engagement of DP2, induces ROS production and MAPK activation. These events augment TNFα synthesis that, via autocrine and/or paracrine signaling induces apoptosis in HL-1 cells and primary cardiomyocytes through activation of extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways.

In principle, 15d-PGJ2 can exert its activity via receptor-dependent and/or -independent pathways [11]. Here we could demonstrate that 15d-PGJ2 signaling is mediated by DP2 (but not DP1 or PPARγ) in a calcium-independent manner (Fig. 6A/B). DP1 has been primarily reported to regulate dendritic cell function [44] while DP2 was suggested to promote inflammatory pathways [45]. 13,14-Dihydro-15-keto PGD2 is a selective DP2 agonist [46], while little information is available about the ability of 15d-PGJ2 to stimulate DP1 [24] and/or DP2 receptors [47].

Results obtained here clearly indicate that 15d-PGJ2-dependent signaling events are mediated via DP2 in HL-1 cells and primary murine cardiomyocytes. In line, we have observed potent activation of ROS production and stimulation of the p38 and p42/44 MAPK pathways by 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 2).

During the present study MAPK activation started at low micromolar concentrations (Fig. 1A). From previous studies it was concluded that only a minor fraction (approx. 4%) of exogenously added 15d-PGJ2 is biologically active while the remainder is either trapped or metabolized [24]. Taking this into account, concentrations of 15 μM 15d-PGJ2 used for HL-1 cells in the present study result in approx. 20 ng/ml active compound, a concentration that would parallel levels of at least 5 ng/ml detected under in vivo inflammatory conditions [24]. Most importantly, 15d-PGJ2 concentrations used in primary cardiomyocytes for activation of MAPK, TNFα induction and subsequent cell death are in the low nanomolar range (Fig. 7). Thus our in vitro findings suggest that low agonist concentrations may be operative under in vivo conditions.

To the best of our knowledge we are the first to show that ROS formation as well as p38 and p42/44 MAPK activation (preceding TNFα induction) by 15d-PGJ2 in cardiomyocytes is dependent on its reactive α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group, as 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 failed to induce these signaling cascades. Thus, the electrophilic carbon center in the ring structure makes PGs susceptible to undergo reactions with nucleophiles such as the free sulfhydryl group of cysteine residues located in reduced glutathione or cellular proteins [10] that so far have not been characterized in detail during myocardial apoptosis.

In terms of nuclear receptor activation, it was demonstrated that 15d-PGJ2 modulates inflammatory markers in neonatal cardiac cells via PPARγ-dependent and -independent pathways. The observed 15d-PGJ2-induced effects are independent of DP1- and PPARγ-mediated pathways in cardiomyocytes. In contrast to previous findings [32] where 15d-PGJ2 was reported to promote endothelial cell apoptosis via the ROS/p53 or ROS/MAPK/p53 axis, phosphorylation of p53 was not observed in the present study (Supplement Fig. X).

Our findings suggest that 15d-PGJ2 promotes ROS-dependent p38 and p42/44 MAPK activation (Fig. 1E). The p42/44 MAPK signaling is thought to promote cell survival under conditions of mild oxidative stress whereas the stress activated protein kinase p38 seems to induce cell death as a response to oxidative injury [48]. In line with results of the present study p38 MAPK activation can induce the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis although the ultimate outcome of SAPK signaling cascades appears to be cell context specific [49]. Oxidative stress-mediated activation of p42/44 MAPK appears to proceed via Raf activation, thiol modification of tyrosine kinase receptors, or oxidative inactivation of protein phosphatases. The activation of p38 (or more generally the SAPK pathway) by ROS results in apoptosis where apoptosis-signaling kinase 1 appears to play an important role as redox sensor for initiation of the SAPK response [49]. Which one of these pathways is activated in response to ROS generation in 15d-PGJ2-treated HL-1 cardiomyocytes or primary cardiomyocytes is currently unclear and was not addressed experimentally during the present study.

15d-PGJ2 suppresses the immune system by PPARγ-mediated activation of apoptosis in immune cells [50]. Previous studies have shown that PPARγ ligands including 15d-PGJ2 may inhibit cardiac hypertrophy in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes [51]. Cardioprotective effects of 15d-PGJ2 include upregulation of PPARγ, expression of heme oxygenase 1, and inhibition of activation of NF-κB during ischemia–reperfusion injury [52]. Furthermore, administration of 15d-PGJ2 suppressed (i) expression of IL-1 (mRNA and protein level) in experimental autoimmune myocarditis [53] as well as (ii) LPS-induced expression of CXC chemokines and ROS-mediated expression of IL-8 (mRNA and protein level) in rat cardiomyocytes [54]. The collective results suggest that 15d-PGJ2 acts sequentially through PPARγ activation, IκB induction, blockage of NF-κB activation, and inhibition of inflammatory cytokine expression [55]. However, such an anti-inflammatory mechanism involving modulation of PPARγ (Figs. 2 and 3) and NF-κB (Fig. 3) was not observed in the present study.

A series of studies confirmed that MI is accompanied by myocyte apoptosis (for review see [56]). 15d-PGJ2 attenuated anti-apoptotic effects of endothelin-1 in primary rat cardiomyocytes [57]. Importantly, inflammatory cytokines derived from circulating blood cells [58] or local synthesis are inducers of the apoptotic machinery in cardiomyocytes. Among these, IL-1 [59,60], IL-6 [61,62], IL-17 [63] and TNFα [64–66] are the most potent mediators of cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac remodeling. Our observations that TNFα is highly upregulated in 15d-PGJ2-stimulated HL-1 cells as well as primary cardiomyocytes and that pharmacological as well as genetic interference with this pathway effectively impairs extrinsic/intrinsic apoptotic routes (Figs. 5D/F; 7C) are in line with these observations. In vivo, heart specific overexpression of secretable TNFα in mice augmented cardiomyocyte apoptosis through activation of multiple death pathways [34]. Thus, the contribution of inflammatory cells on 15d-PGJ2-induced pro-inflammatory cascades in cardiomyocytes under in vivo conditions remains to be elucidated.

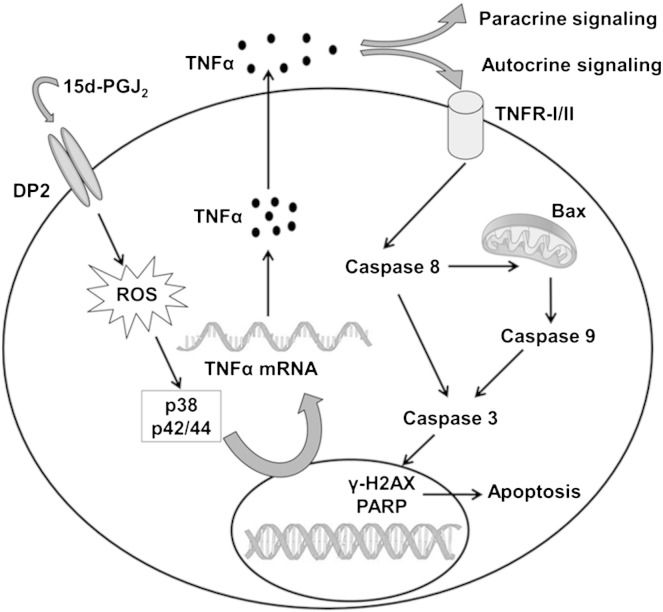

Cardiac myocyte apoptosis has been identified as a mechanism of cell death during CAD and MI. The incidence of apoptosis varies significantly and the exact pathophysiological events and underlying signaling (mostly overlapping) pathways induced by inflammatory cytokines still remain to be clarified in detail for effective therapeutic treatment. Activation of TNFα is undoubtedly one of the major causes for myocardial apoptosis leading to cardiac remodeling through multiple routes. We here show engagement of 15d-PGJ2, a dehydration product of PGD2, in this process. Experimental work performed during the present study suggests that the DP2-ROS-MAPK axis plays a central role in this signaling circuit that ultimately leads to cardiomyocyte death via TNFα (Fig. 8). Both, p38 and p42/44 MAPK inhibitors were found to be equally effective to attenuate TNFα synthesis in cardiomyocytes in response to 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 8.

Summary of 15d-PGJ2-induced signaling events in cardiomyocytes observed during the present study.

Previous studies clearly revealed that inhibition/antagonism of TNF represents one option to reduce cell death in the myocardium. However, TNF blockage would not prevent upstream engagement of DP2, generation of ROS and activation of the MAPK pathways that in turn might adversely affect other signaling cascades. From the present study (Fig. 8) it seems conclusive that blockage of DP2 receptors might serve as a novel and potential target to alleviate myocardial injury in response to COX-derived eicosanoids e.g. PGD2 and its dehydration product 15d-PGJ2 during CAD and MI. Data of the present study, together with the reported high expression of DP2 mRNA in human heart [25] suggest that DP2 antagonism could provide a potential pharmacological approach to interfere with PGD2-/15d-PGJ2-mediated cardiomyocyte injury.

Acknowledgements

HL-1 cells were provided by Dr. Claycomb (New Orleans, LA, USA). This work was supported by the FWF (SFB-LIPOTOX F3007 and W1241; C.N.K. was funded by W1226-B18 within the DK-MCD at the MUG).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material.

References

- 1.Agrawal R., Agrawal N., Koyani C.N., Singh R. Molecular targets and regulators of cardiac hypertrophy. Pharmacol Res. 2010;61:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalra B.S., Roy V. Efficacy of metabolic modulators in ischemic heart disease: an overview. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:292–305. doi: 10.1177/0091270010396042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumont E.A., Hofstra L., van Heerde W.L. Cardiomyocyte death induced by myocardial ischemia and reperfusion: measurement with recombinant human annexin-V in a mouse model. Circulation. 2000;102:1564–1568. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.13.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryu S.K., Mallat Z., Benessiano J. Phospholipase A2 enzymes, high-dose atorvastatin, and prediction of ischemic events after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2012;125:757–766. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross G.J., Falck J.R., Gross E.R., Isbell M., Moore J., Nithipatikom K. Cytochrome P450 and arachidonic acid metabolites: role in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury revisited. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu H., Liu J.Y., Wei D. Cardiac-generated prostanoids mediate cardiac myocyte apoptosis after myocardial ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:336–345. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell W.S. 15-Deoxy-delta, 12,14-PGJ2: endogenous PPARgamma ligand or minor eicosanoid degradation product? J Clin Invest. 2003;112:828–830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuligoi R., Schmidt R., Geisslinger G., Kollroser M., Peskar B.A., Heinemann A. PGD2 metabolism in plasma: kinetics and relationship with bioactivity on DP1 and CRTH2 receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibata T., Kondo M., Osawa T., Shibata N., Kobayashi M., Uchida K. 15-deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2. A prostaglandin D2 metabolite generated during inflammatory processes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10459–10466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straus D.S., Glass C.K. Cyclopentenone prostaglandins: new insights on biological activities and cellular targets. Med Res Rev. 2001;21:185–210. doi: 10.1002/med.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X., Young H.A. PPAR and immune system—what do we know? Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1029–1044. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00057-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim H.J., Lee K.S., Lee S. 15d-PGJ2 stimulates HO-1 expression through p38 MAP kinase and Nrf-2 pathway in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;223:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S.J., Kim M.S., Park J.Y., Woo J.S., Kim Y.K. 15-Deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 induces apoptosis via JNK-mediated mitochondrial pathway in osteoblastic cells. Toxicology. 2008;248:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung W.K., Park I.S., Park S.J. The 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits LPS-stimulated AKT and NF-kappaB activation and suppresses interleukin-6 in osteoblast-like cells MC3T3E-1. Life Sci. 2009;85:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giri S., Rattan R., Singh A.K., Singh I. The 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits the inflammatory response in primary rat astrocytes via down-regulating multiple steps in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt-NF-kappaB-p300 pathway independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Immunol. 2004;173:5196–5208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim E.H., Na H.K., Kim D.H. 15-Deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 induces COX-2 expression through Akt-driven AP-1 activation in human breast cancer cells: a potential role of ROS. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:688–695. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba T., Ueki S., Ito W. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 induces IL-8 and GM-CSF in a human airway epithelial cell line (NCI-H292) Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149(Suppl. 1):77–82. doi: 10.1159/000211377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen Z.N., Nishida K., Doi H. Suppression of chondrosarcoma cells by 15-deoxy-Delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 is associated with altered expression of Bax/Bcl-xL and p21. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haskew-Layton R.E., Payappilly J.B., Xu H., Bennett S.A., Ratan R.R. 15-Deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) protects neurons from oxidative death via an Nrf2 astrocyte-specific mechanism independent of PPARgamma. J Neurochem. 2013;124:536–547. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferguson H.E., Kulkarni A., Lehmann G.M. Electrophilic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands have potent antifibrotic effects in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:722–730. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0006OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J.W., Li M.H., Jang J.H. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) rescues PC12 cells from H2O2-induced apoptosis through Nrf2-mediated upregulation of heme oxygenase-1: potential roles of Akt and ERK1/2. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:1577–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitz K., Windischhofer W., Leis H.J., Huber E., Kollroser M., Malle E. 15-Deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 induces Cox-2 expression in human osteosarcoma cells through MAPK and EGFR activation involving reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:854–865. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricciotti E., FitzGerald G.A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:986–1000. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajakariar R., Hilliard M., Lawrence T. Hematopoietic prostaglandin D2 synthase controls the onset and resolution of acute inflammation through PGD2 and 15-deoxyDelta12 14 PGJ2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20979–20984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707394104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawyer N., Cauchon E., Chateauneuf A. Molecular pharmacology of the human prostaglandin D2 receptor, CRTH2. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:1163–1172. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lotz C., Lange M., Redel A. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma mediates the second window of anaesthetic-induced preconditioning. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:317–324. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.055590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claycomb W.C., Lanson N.A., Jr., Stallworth B.S. HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacherer M., Sedej S., Wakula P. JTV519 (K201) reduces sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2)(+) leak and improves diastolic function in vitro in murine and human non-failing myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rauh A., Windischhofer W., Kovacevic A. Endothelin (ET)-1 and ET-3 promote expression of c-fos and c-jun in human choriocarcinoma via ET(B) receptor-mediated G(i)- and G(q)-pathways and MAP kinase activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:13–24. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossmann C., Rauh A., Hammer A. Hypochlorite-modified high-density lipoprotein promotes induction of HO-1 in endothelial cells via activation of p42/44 MAPK and zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;509:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semlitsch M., Shackelford R.E., Zirkl S., Sattler W., Malle E. ATM protects against oxidative stress induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10:848–860. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho T.C., Chen S.L., Yang Y.C. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 induces vascular endothelial cell apoptosis through the sequential activation of MAPKS and p53. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30273–30288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804196200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuligoi R., Sturm E., Luschnig P. CRTH2 and D-type prostanoid receptor antagonists as novel therapeutic agents for inflammatory diseases. Pharmacology. 2010;85:372–382. doi: 10.1159/000313836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haudek S.B., Taffet G.E., Schneider M.D., Mann D.L. TNF provokes cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac remodeling through activation of multiple cell death pathways. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2692–2701. doi: 10.1172/JCI29134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gururaja T.L., Yung S., Ding R. A class of small molecules that inhibit TNFalpha-induced survival and death pathways via prevention of interactions between TNFalphaRI, TRADD, and RIP1. Chem Biol. 2007;14:1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Das D.K., Engelman R.M., Rousou J.A., Breyer R.H., Otani H., Lemeshow S. Role of membrane phospholipids in myocardial injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:H71–H79. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.1.H71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chien K.R., Han A., Sen A., Buja L.M., Willerson J.T. Accumulation of unesterified arachidonic acid in ischemic canine myocardium. Relationship to a phosphatidylcholine deacylation-reacylation cycle and the depletion of membrane phospholipids. Circ Res. 1984;54:313–322. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chien K.R., Sen A., Reynolds R. Release of arachidonate from membrane phospholipids in cultured neonatal rat myocardial cells during adenosine triphosphate depletion. Correlation with the progression of cell injury. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:1770–1780. doi: 10.1172/JCI111889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leong L.L., Sturm M.J., Ismail Y., Stephens C.J., Taylor R.R. Plasma phospholipase A2 activity in clinical acute myocardial infarction. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1992;19:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1992.tb00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tokudome S., Sano M., Shinmura K. Glucocorticoid protects rodent hearts from ischemia/reperfusion injury by activating lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase-derived PGD2 biosynthesis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1477–1488. doi: 10.1172/JCI37413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eguchi Y., Eguchi N., Oda H. Expression of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (beta-trace) in human heart and its accumulation in the coronary circulation of angina patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14689–14694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bell-Parikh L.C., Ide T., Lawson J.A., McNamara P., Reilly M., FitzGerald G.A. Biosynthesis of 15-deoxy-delta, 12,14–PGJ2 and the ligation of PPARgamma. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:945–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI18012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirai H., Abe H., Tanaka K. Gene structure and functional properties of mouse CRTH2, a prostaglandin D2 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:797–802. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammad H., de Heer H.J., Soullie T., Hoogsteden H.C., Trottein F., Lambrecht B.N. Prostaglandin D2 inhibits airway dendritic cell migration and function in steady state conditions by selective activation of the D prostanoid receptor 1. J Immunol. 2003;171:3936–3940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.3936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujitani Y., Kanaoka Y., Aritake K., Uodome N., Okazaki-Hatake K., Urade Y. Pronounced eosinophilic lung inflammation and Th2 cytokine release in human lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:443–449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hatanaka M., Shibata N., Shintani N. 15d-prostaglandin J2 enhancement of nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth is blocked by the chemoattractant receptor- homologous molecule expressed on T-helper type 2 cells (CRTH2) antagonist CAY10471 in PC12 cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;113:89–93. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10001sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monneret G., Li H., Vasilescu J., Rokach J., Powell W.S. 15-Deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandins D2 and J2 are potent activators of human eosinophils. J Immunol. 2002;168:3563–3569. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuzawa A., Ichijo H. Stress-responsive protein kinases in redox-regulated apoptosis signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:472–481. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trachootham D., Lu W., Ogasawara M.A., Nilsa R.D., Huang P. Redox regulation of cell survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1343–1374. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris S.G., Phipps R.P. The nuclear receptor PPAR gamma is expressed by mouse T lymphocytes and PPAR gamma agonists induce apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1098–1105. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1098::aid-immu1098>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto K., Ohki R., Lee R.T., Ikeda U., Shimada K. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators inhibit cardiac hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2001;104:1670–1675. doi: 10.1161/hc4001.097186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wayman N.S., Hattori Y., McDonald M.C. Ligands of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR-gamma and PPAR-alpha) reduce myocardial infarct size. FASEB J. 2002;16:1027–1040. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0793com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan Z., Liu Y., Liu Y. Peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor-gamma ligands ameliorate experimental autoimmune myocarditis. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:685–694. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu J., Xia Q., Zhang Q. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 and pioglitazone inhibit hydroxyl peroxide-induced TNF-alpha and lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine expression in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Shock. 2009;32:317–324. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31819c374c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan Z., Liu Y., Liu Y. Cardioprotective effects of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma activators on acute myocarditis: anti-inflammatory actions associated with nuclear factor kappaB blockade. Heart. 2005;91:1203–1208. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.046292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bartling B., Holtz J., Darmer D. Contribution of myocyte apoptosis to myocardial infarction? Basic Res Cardiol. 1998;93:71–84. doi: 10.1007/s003950050065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ehara N., Hasegawa K., Ono K. Activators of PPARgamma antagonize protection of cardiac myocytes by endothelin-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arras M., Strasser R., Mohri M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is expressed by monocytes/macrophages following cardiac microembolization and is antagonized by cyclosporine. Basic Res Cardiol. 1998;93:97–107. doi: 10.1007/s003950050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki K., Murtuza B., Smolenski R.T. Overexpression of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist provides cardioprotection against ischemia–reperfusion injury associated with reduction in apoptosis. Circulation. 2001;104:I308-13. doi: 10.1161/hc37t1.094871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishikawa K., Yoshida M., Kusuhara M. Left ventricular hypertrophy in mice with a cardiac-specific overexpression of interleukin-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H176–H183. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00269.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang H., Wang H.Y., Bassel-Duby R. Role of interleukin-6 in cardiac inflammation and dysfunction after burn complicated by sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2408–H2416. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01150.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsushita K., Iwanaga S., Oda T. Interleukin-6/soluble interleukin-6 receptor complex reduces infarct size via inhibiting myocardial apoptosis. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1210–1223. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liao Y.H., Xia N., Zhou S.F. Interleukin-17A contributes to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating cardiomyocyte apoptosis and neutrophil infiltration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kubota T., Miyagishima M., Frye C.S. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor- alpha activates both anti- and pro-apoptotic pathways in the myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1331–1344. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kubota T., McTiernan C.F., Frye C.S. Dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circ Res. 1997;81:627–635. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engel D., Peshock R., Armstong R.C., Sivasubramanian N., Mann D.L. Cardiac myocyte apoptosis provokes adverse cardiac remodeling in transgenic mice with targeted TNF overexpression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1303–H1311. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00053.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.