Abstract

Innate immune and inflammatory responses are involved in myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Interleukin (IL)-37 is a newly identified member of the IL-1 family, and functions as a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity and inflammation. However, its role in myocardial I/R injury remains unknown. I/R or sham operations were performed on male C57BL/6J mice. I/R mice received an injection of recombinant human IL-37 or vehicle, immediately before reperfusion. Compared with vehicle treatment, mice treated with IL-37 showed an obvious amelioration of the I/R injury, as demonstrated by reduced infarct size, decreased cardiac troponin T level and improved cardiac function. This protective effect was associated with the ability of IL-37 to suppress production of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and neutrophil infiltration, which together contributed to a decrease in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. In addition, we found that IL-37 inhibited the up-regulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 expression and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) activation after I/R, while increasing the anti-inflammatory IL-10 level. Moreover, the administration of anti-IL-10R antibody abolished the protective effects of IL-37 in I/R injury. In-vitro experiments further demonstrated that IL-37 protected cardiomyocytes from apoptosis under I/R condition, and suppressed the migration ability of neutrophils towards the chemokine LIX. In conclusion, IL-37 plays a protective role against mouse myocardial I/R injury, offering a promising therapeutic medium for myocardial I/R injury.

Keywords: apoptosis, IL-37, I/R injury, ROS, TLR-4/NF-κB

Introduction

Myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury is regarded as an inflammatory condition characterized by an innate immune response, which is triggered by endogenous alarm signals referred to as ‘danger-associated molecular patterns’ (DAMPs) [1–3]. These DAMPs are recognized mainly by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [4]. TLRs on leucocytes and parenchymal cells have been showed to respond to such signals and possess an essential role in sterile pathological cardiovascular diseases [5,6]. DAMPs that bind to TLRs lead to the activation of downstream signalling pathways, including those of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase [6], which induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules [6,7]. The subsequent neutrophil activation and leucocyte infiltration result in further cytokine secretion, oxidative stress and protease release, which directly exacerbate myocardial and endothelial injury to form a positive feedback loop and aggravate I/R injury [8,9].

Experimental studies targeting innate immunity have reduced the infarct size and improved cardiac function after I/R in mice [4]. The infarct size was reduced significantly in TLR-4-deficient mice after I/R [3], and these mice exhibited less inflammation than wild-type mice, which was consistent with a report of treatment with eritoran that reducd the binding of lipid A [a biologically active part of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)] to TLR-4 [10]. Moreover, targeting downstream effectors of TLR such as myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) also significantly reduced infarct size and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [e.g. interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α] via NF-κB [11,12]. Furthermore, reactive oxygen species (ROS), which further contributes to cardiomyocyte and endotheliocyte dysfunction, increases the production of proinflammatory cytokines and expression of adhesion molecules to exacerbate myocardial damage and death [8]. This process has been shown to depend upon TLR-4 and be associated with the release of high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), a highly proinflammatory conserved nuclear protein [13,14]. Thus, targeting innate immunity shows promise as a therapy for I/R injury.

IL-37 is a newly identified member of the IL-1 family, known formerly as IL-1F7, IL-1H and IL-1H4. It exists in several organs and tissues including the brain, kidney, heart, bone marrow and testis in specific isoforms. IL-37 is also expressed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), monocytes, dendritic cells and epithelial cells and acts as a natural suppressor of innate inflammatory and immune responses [15,16]. Physiologically, IL-37 is expressed at low level and can be up-regulated in an inducible manner [16,17]. In vitro, TLR agonists and a variety of cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-18, TNF-α, interferon (IFN)-γ and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β can also significantly up-regulate the expression of IL-37, which subsequently suppresses the proinflammatory response [16]. IL-37 has repressive effects on LPS-stimulated cells, such as macrophages and endotheliocytes, which implies that it may impact signalling intermediates that are specific to the TLR-4 pathway [6,16]. Studies have also shown that IL-37 provided distinct anti-inflammatory effects in vivo in models of septic shock, drug-induced colitis and hepatic I/R [16,18,19]. Most importantly, our study revealed that circulating levels of IL-37 was obviously elevated in patients with acute myocardial infarction [20]; however, the roles of IL-37 in myocardial I/R have not been investigated.

In the current study, we hypothesized that IL-37 can reduce the infarct size and improve cardiac function after I/R in mice. We investigated the influence of IL-37 on the innate immunity response of I/R mice by focusing mainly on infiltrating neutrophils and the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Furthermore, the effect of I/R on cardiomyocyte apoptosis was also assessed in vivo and in vitro. Finally, we also investigated the possible mechanism by which IL-37 mitigated the I/R injury in vivo.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental design male

Male C57BL/6 mice aged 8–10 weeks were purchased from Beijing University (Beijing, China). The mice received a standard diet and water ad libitum at the Tongji Medical School Animal Care Facility according to institutional guidelines. The mice underwent either sham or I/R surgery. The treatment groups received 2 μg of recombinant human IL-37 (Adipogen AG, Liestal, Switzerland) (dissolved in 200 μl normal saline) or 200 μl normal saline (vehicle), which were administered via the tail vein before reperfusion in I/R mice. The blocking group consisted of IL-37-treated I/R mice that simultaneously received 200 μg of anti-IL-10R monoclonal antibody (mAb) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or 100 μg of anti-TGF-β (R&D Systems), or isotype mAb intraperitoneally (i.p.) before reperfusion [18,21]. The study included five experimental groups: sham (sham), untreated I/R, I/R + vehicle, I/R + IL-37 and I/R + IL-37 + anti-IL-10R/anti-TGF-β/isotype mAb (each group contained six to eight mice). In addition to the above treatment, the cytokine or antibody injection was repeated every 24 h over a 72-h reperfusion period. The serum troponin T levels were measured 24 h after reperfusion and the infarct size and cardiac function were assessed 24 and 72 h after reperfusion. Apoptosis, ROS production, chemokine expression and inflammation response were analysed in the mice 4 and 24 h after reperfusion, while the infiltration of inflammatory cells and neutrophils were detected 4 h after reperfusion. All animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Utilization Committee of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Myocardial I/R injury in vivo and infarct area assessment

The mice were anaesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg), intubated orally, and connected to a rodent ventilator. A left thoracotomy was performed by a horizontal incision at the third intercostal space. I/R was achieved by ligating the anterior descending branch of the left coronary artery with an 8-0 silk suture, and silicon tubing (PE-10) was placed on top of the left anterior descending coronary artery, 2 mm below the border between the left atrium and left ventricle (LV). Ischaemia was confirmed by an electrocardiograph (ECG) change (ST elevation). The sham-operated animals were subjected to the same surgical procedures, except that the suture was passed under the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, but not tied. After 30 min of occlusion, the silicon tubing was removed to achieve reperfusion, and the rib space and overlying muscles were closed. Echocardiographic analyses were performed before euthanasia. Twenty-four h after reperfusion the animals were reanaesthetized and the heart was arrested at the diastolic phase by KCl (20 mM) injection, the chest was opened and the ascending aorta was cannulated and perfused with saline to wash out the blood. The left anterior descending coronary artery was occluded with the same suture, which had been left at the site of the ligation. To demarcate the ischaemic area at risk (AAR), Alcian blue dye (1%) was perfused into the aorta and coronary arteries. The hearts were excised, and the LVs were sliced into 1-mm-thick cross-sections. The heart sections were then incubated with a 1% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution at 37°C for 15 min. The infarct area (pale), the AAR (not blue) and the total LV area from both sides of each section were measured using Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA), and the obtained values were averaged. The percentages of the area of infarction and AAR of each section were multiplied by the weight of the section and then totalled for all sections.

Echocardiographic analysis of cardiac function

A GE Vivid 4 ultrasound machine equipped with an 18-MHz phase array linear transducer was used (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA). The mice were anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg). M-mode images were used to measure LV fractional shortening (FS) and LV ejection fraction (EF), which were acquired by a technician who was blinded to the treatment groups.

Serum troponin T

The blood concentrations of troponin T were measured as an index of cardiac cellular damage using a quantitative rapid assay kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Evaluation of apoptosis in tissue sections and cardiomyocytes

DNA fragmentation was detected in situ with the use of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL), as described previously [22]. The hearts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, cut into 6-μm-thick sections and treated as instructed in the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The nuclear density was determined via manual counting of the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained nuclei in five fields for each animal with a ×40 objective, and the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei was determined by examining the entire section with the same power objective. The cardiac caspase-3 activity was measured using a caspase colorimetric assay kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). The absorbance of the pnitroaniline cleaved by caspase was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader (ELx800; Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Cultured cardiomyocytes were exposed to I/R with or without IL-37, and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL staining according to the manufacturer's directions. The nuclei were identified by staining with DAPI. Five randomly chosen fields from each dish were used to determine the percentage of apoptotic nuclei.

Dihydroethidium (DHE) detection

DHE staining was performed as described previously [22]. After harvest, the heart tissues were embedded immediately in an optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound and stored at −80°C. The unfixed frozen samples were cut into 6-μm-thick sections and placed on glass slides. DHE (10 μmol/l) was applied to each tissue section and the sections were covered with a coverslip. The slides were incubated in a light-protected humidified chamber at 37°C for 30 min. The ethidium fluorescence (excitation at 490 nm, emission at 610 nm) was examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Lipid peroxidation detection

The ischaemic zones were assessed for lipid peroxidation. The left ventricular tissues from the sham-operated animals at 4 h served as controls. The frozen tissues were homogenized in 250 μl of ice-cold 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7·4). After centrifugation, 200 μl of supernatant were analysed for lipid peroxidation products [malondialdehyde (MDA)/4-hydroxyalkenals (4-HNE)] using a lipid peroxidation assay kit (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany).

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) detection

MPO activity was measured as an indicator of neutrophil infiltration in the ischaemic myocardium using a Myeloperoxidase Colorimetric Activity Assay Kit (Biovision, Milpitas, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One unit of MPO is defined as the amount of MPO that hydrolyzes the substrate and generates taurine chloramine to consume 1 mmol trinitrobenzene (TNB) per min at 25°C.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

The heart tissues were fixed with 4% formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 6-mm-thick slices. To investigate the inflammatory cell infiltration after I/R injury, the sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin to further identify neutrophils with LY-6G (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) as per standard protocols.

Western blot analysis

The left ventricular samples were homogenized in whole cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) that contained additional phosphatase and protease inhibitors. The left ventricular homogenates were then centrifuged at 18 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was measured in the supernatants using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride microporous membranes (Bio-Rad) and probed with primary antibodies. The antibodies used in this study included anti-phosphorylated (phospho) p65 (Ser536) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA CA), anti-TLR-4 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). An Invitrogen kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to visualize the protein bands. Densitometry was performed using the Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). To standardize the densitometry measurements between individual samples, the ratios of phosphor-p65 or TLR-4 to GAPDH were calculated for statistical analyses.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for chemokine and proinflammatory factors

The heart tissue was homogenized, centrifuged for 10 min at 12 000 g and 4°C, and the supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C. The levels of lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine (LIX), cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (KC), macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 and TGF-β in heart tissue and serum were measured using special commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems). All tests on samples and standards were performed in duplicate. The results are reported as pg/mg protein or pg/ml.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells or tissues using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mRNA levels of target genes were quantified using SYBR Green Master Mix (Takara Biotechnology) with the ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detector system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Each reaction was performed in duplicate, and changes in relative gene expression normalized to GAPDH levels were determined using the relative threshold cycle method. The primer sequences are shown in the Supporting information, Table S1.

Myocardial cell culture

Neonatal cardiomyocytes were isolated and cultured using previously described methods [23]. Briefly, after cervical dislocation, the hearts from 1-day-old C57BL/6 mice were removed, cut into small chunks and washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). The tissues were then incubated in 4 ml trypsin/ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution (gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 4°C for 30 min with rotation. The digestion was stopped by the addition of 6 ml Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS; gibco). After centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 min, the supernatant was removed and the tissues were incubated in 4 ml Liberase TH (0·1 U/ml in HBSS, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) at 37°C for 15 min. The supernatant containing the cells released to DMEM–20% FCS was removed, and fresh Liberase TH was added to the undigested tissues, which were then incubated for a further 15 min. This digestion procedure was repeated until most of the cells had been released from the ventricular tissue and the obtained cells were resuspended in DMEM. All collected cells were filtered through a nylon cell strainer (70 μm size; BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and seeded into fibronectin-coated 12-well tissue culture plates (Costar; Corning, New York, NY, USA). After 1 h of incubation with 5% CO2 at 37°C, the attached fibroblasts were discarded and the cardiomyocytes in the supernatant were enriched and seeded into fibronectin-coated tissue culture plates after the cell concentration was adjusted. The cardiomyocytes were used in experiments when they had formed a confluent monolayer and beat in synchrony after 72 h.

Exposure of cardiomyocytes to I/R

A hypoxia/reoxygenation injury was induced by placing the cardiomyocytes in a hypoxia chamber filled with 5% CO2 and 95% N2 at 37°C in a glucose-free DMEM with or without IL-37 treatment for 1 h, and the cells were then reoxygenated with 5% CO2 and 95% air for 4 h in DMEM containing 10% serum and 5 mM glucose. In addition, a portion of the cardiomyocytes was cultivated continuously with 5% CO2 and 95% air for 5 h in DMEM containing 10% serum and 5 mM glucose to serve as a control. At the end of I/R stress, the cells were examined to measure apoptosis by TUNEL labelling and reverse transcription (RT)–PCR.

Isolation of neutrophils

Neutrophils were isolated from the marrow of femurs and tibias of adult C57BL/6 mice, as described previously [24]. The mice were anaesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) before euthanasia by cervical dislocation. The neutrophils in bone marrow were negatively isolated using the Mouse Neutrophil Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity of neutrophils was evaluated using anti-CD11b, anti-Gr-1 and anti-F4/80 antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) conjugated with peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP), phycoerythrin (PE) and allophycocyanin (APC), respectively.

In-vitro migration assay

Cell migration was measured using Transwell inserts with polycarbonate filters (5 μm pores for neutrophils) preloaded in 24-well tissue culture plates (Millipore Co., Billerica, MA, USA). The cells were preincubated with IL-37 or vehicle for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 1 × 106 cells were placed into the upper chamber of the Transwell insert and the lower compartment was loaded with medium containing LIX (10 ng/ml) [25] (R&D Systems). After 2 h, the number of migrated cells was determined using a haemocytometer. A chemotaxis index (CI: the number of cells migrating towards chemokine containing media/number of cells migrating towards control media) was calculated.

Statistics

The data are presented as the means ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) unless indicated otherwise. The differences were evaluated using unpaired Student's t-tests between two groups when the data were normally distributed and group variances were equal. The Mann–Whitney rank sum test was used when the data were not normally distributed or if group variances were unequal. A one-way analysis of variance (anova) was used for multiple comparisons followed by a post-hoc Tukey's procedure for multiple range tests when the data were normally distributed and the group variances were equal. The Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn's test, was used when the group data were not normally distributed or if the group variances were unequal. GraphPad Prism version 6·0 software was used for statistical analyses, and the statistical significance was set at P < 0·05.

Results

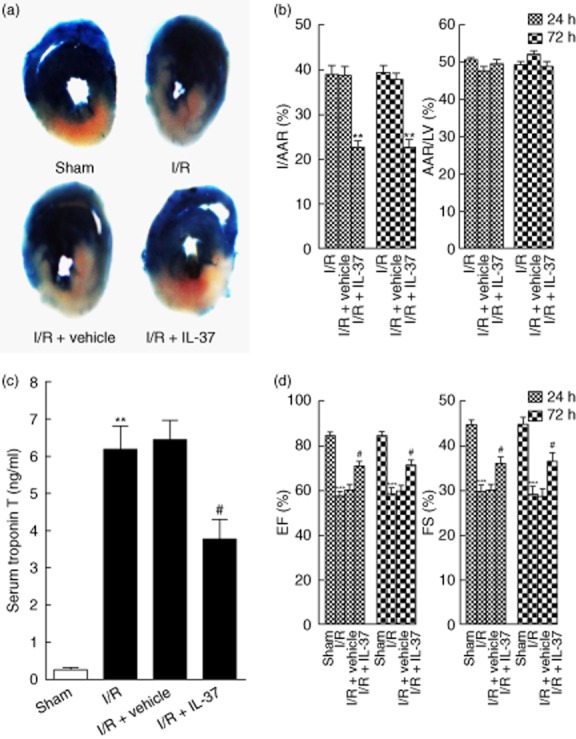

IL-37 protects against myocardial I/R injury in mice

The AAR : LV ratio did not differ between untreated and IL-37-treated groups (50·3 ± 1·9 versus 49·0 ± 2·7%; P > 0·05; Fig. 1b), which indicated that ligature was reproducibly achieved on the same level of LAD. Mice treated with IL-37 showed a significantly reduced infarct size within the AAR by 41·5% compared with the untreated group (22·7 ± 3·3 versus 38·8 ± 5·2%; P < 0·01; Fig. 1a,b). The cardiac troponin T (cTnT) level in the serum, a direct index of myocyte damage, was also significantly lower in the IL-37 treatment group (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Interleukin (IL)-37 reduces myocardial infarct size and improves left ventricular function following ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R). (a) Representative illustrations of infarct size after 24 h as stained by Evans Blue and triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC); the non-ischaemic area is indicated in blue, the area at risk (AAR) in red and the infarct area in white. (b) Quantification of infarct area/area at risk (I/AAR) and area at risk/left ventricular area (AAR/LV) 24 h and 72 h after reperfusion (n = 6). (c) Serum cardiac troponin T (cTnT) was measured in different groups at 24 h after I/R (n = 6–8). (d) Ejection fraction (%EF) and fractional shortening (%FS) 24 h and 72 h after reperfusion (n = 6). **P < 0·01 versus sham or I/R. ***P < 0·001 versus sham. #P < 0·05 versus I/R.

As shown in Fig. 1d, EF and FS both decreased significantly compared with the sham group 24 and 72 h after I/R. However, IL-37 significantly attenuated the I/R-induced cardiac dysfunction, as revealed by the higher EF and FS 24 and 72 h after reperfusion (Fig. 1d). These results confirmed that IL-37 played a protective role in mouse myocardial I/R injury.

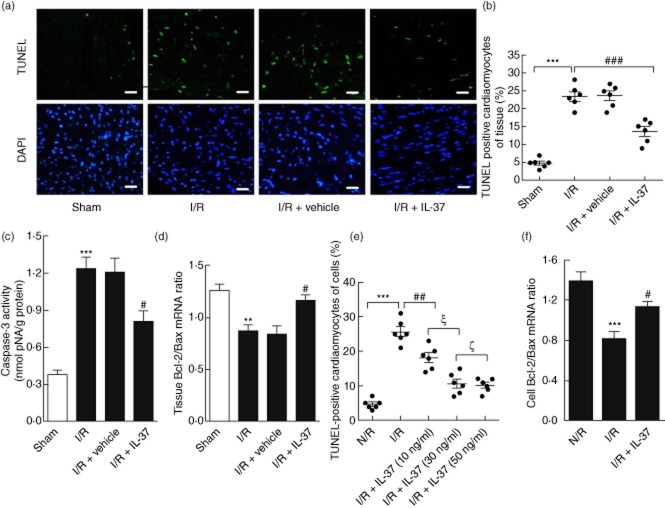

IL-37 limits cardiomyocytes apoptosis and oxidative stress after I/R

Apoptosis has been proposed to be an important mechanism for myocardial I/R injury [26]. As shown in Fig. 2a,b, the representative TUNEL-stained sections demonstrated significantly fewer apoptotic cells in the IL-37-treated I/R mice compared with the untreated I/R mice. Furthermore, IL-37 treatment obviously inhibited the activation of caspase-3, as determined by a caspase colorimetric assay of the ischaemic myocardium of I/R mice (Fig. 2c). To analyse the role of IL-37 in contributing to survival against I/R at the cellular level, cultured neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes were subjected to hypoxia and reoxygenation. As expected, pretreatment with IL-37 (30 ng/ml) sufficiently decreased the frequency of apoptotic cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2e).

Figure 2.

Effect of interleukin (IL)-37 on cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. (a) Apoptotic cell nuclei in the ischaemic area were evaluated by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) staining (green) 24 h after reperfusion, and total nuclei by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (blue). Bar, 10 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of percentage of cardiomyocytes undergoing apoptosis in vivo (n = 6). (c) Caspase-3 activity in myocardium was assessed after 4 h of reperfusion (n = 8). (d) The mRNA ratio of Bcl-2/Bax in the heart tissue. (e) Cardiomyocytes were pretreated with IL-37 using different concentrations (10/30/50 ng/ml) for 1 h before ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R), the cardiomyocytes were then harvested for apoptosis detection by TUNEL staining. Quantitative analysis of percentage of cardiomyocytes undergoing apoptosis in vitro (n = 6). (f) Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) determined cardiomyocyte Bcl-2 and Bax levels when pretreated with IL-37 (30 ng/ml). The results were presented as Bcl-2/Bax ratio (n = 6). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001 versus sham or N/R. #P < 0·05; ##P < 0·01; ###P < 0·001 versus I/R or N/R. ξP < 0·001; ζP > 0·05.

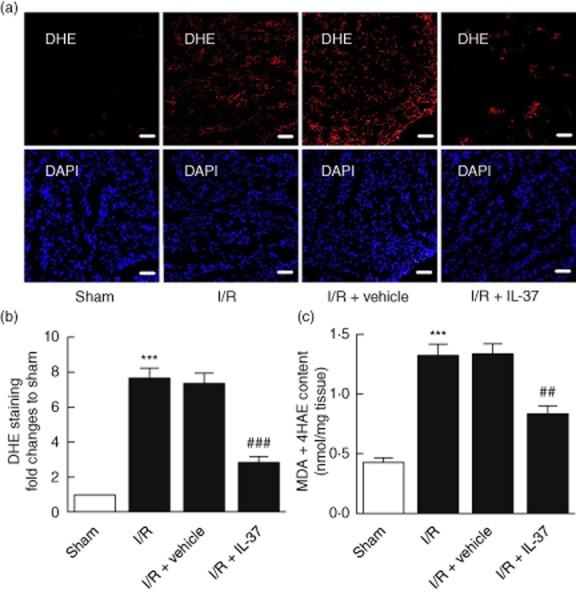

To investigate the mechanisms by which IL-37 protects cardiomyocytes from apoptosis induced by I/R stress, we observed the expression of the Bcl-2 family by RT–PCR of the ischaemic myocardium in vivo and I/R stressed cardiomyocytes in vitro. The Bcl-2/Bax ratio of the IL-37 treated I/R group increased significantly compared with the untreated group (Fig. 2d,f), which may resist I/R-induced apoptosis. As an increased ROS level is a hallmark of oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis [8], we investigated if the decrease in apoptosis by IL-37 was also associated with the change of ROS level in vivo. As shown in Fig. 3a,b, IL-37-treated I/R mice showed remarkably decreased ROS production compared with the untreated group. Consistent with the above result, the ROS-producing activity of cardiac homogenates after I/R, as evaluated with lipid peroxides (malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxyalkenal), was also significantly lower in IL-37-treated I/R mice (Fig. 3c). These results suggested that IL-37 may function by the modulation of anti-and pro-apoptotic molecule ratios of the Bcl-2 family and suppression of ROS production.

Figure 3.

Interleukin (IL)-37 mitigates oxidative stress after I/ ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in mice. (a) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the left ventricle (LV) sections was evaluated with dihydroethidium (DHE) staining 4 h after reperfusion. Bar, 50 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of ROS, as normalized to sham (n = 5–6). (c) Malonaldehyde + 4-hydroxy-alkenals (MDA+ 4HAE) contents in LV sections were evaluated with the lipid peroxidation detection (n = 6). ***P < 0·001 versus sham. ##P < 0·01; ###P < 0·001 versus I/R.

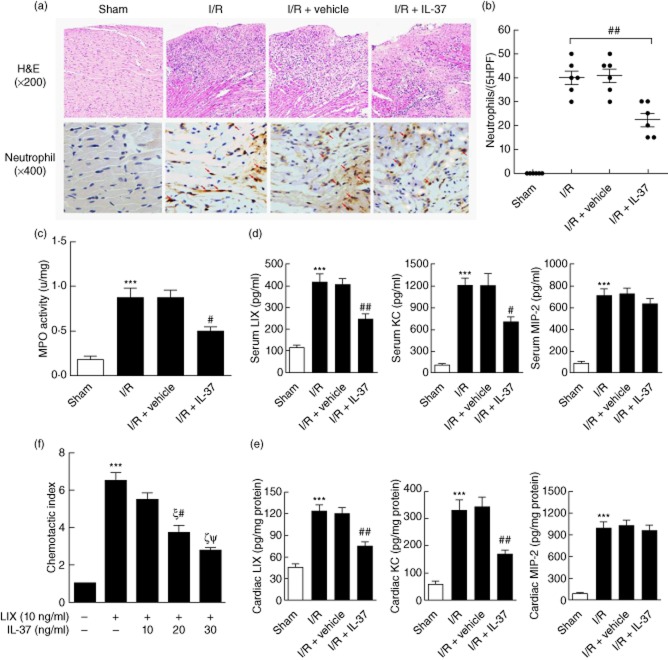

IL-37 inhibits neutrophil recruitment through modulating chemokine expression in vivo and migration ability in vitro

Haematoxylin and eosin staining showed a marked infiltration of inflammatory cells in the I/R-operated mice (Fig. 4a). However, IL-37-treated mice showed less infiltration of inflammatory cells (Fig. 4a), which was consistent with a decrease in apoptotic cells. We further investigated neutrophil infiltration by staining with specific markers. As shown in Fig. 4a,b, IL-37 treatment decreased the infiltration of neutrophils significantly 4 h after I/R injury compared with the control mice, which was confirmed by assaying MPO activity (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Effects of interleukin (IL)-37 on infiltration of neutrophils after ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in mice. (a) Hearts were harvested 4 h after reperfusion and subjected to haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to further identify the enhanced infiltration of neutrophils (4 h) in the ischaemic area of mice heart injured by I/R. (b) The number of stained cells for neutrophils in five × 400 fields were counted for each left ventricle (LV) section, and the mean of three LV sections of one mouse was taken as the number of infiltrated cells (n = 6). (c) Myeloperoxidase (MPO), a biochemical marker of neutrophil infiltration into tissues, was detected in post-ischaemic reperfused myocardium with a colorimetric assay (n = 6). (d) Serum and (e) heart levels of lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine (LIX), cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (KC) and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) after mice myocardial I/R 4 h (n = 6). (f) Neutrophils that had been incubated with the indicated concentrations of IL-37 for 1 h were allowed to migrate through a polycarbonate filter for 2 h towards LIX. The cells present in the lower chamber were counted, and the chemotactic index was then calculated as described in the Methods. ***P < 0·001 versus sham or control. #P < 0·05; ##P < 0·01 versus I/R or group with IL-37 (10 ng/ml).ξP < 0·001 versus group with LIX (10 ng/ml) and no IL-37; ζP < 0·001 versus group with LIX (10 ng/ml) and IL-37 (10 ng/ml). ΨP > 0·05 versus group with LIX (10 ng/ml) and IL-37 (20 ng/ml).

The CXC glutamic acid–leucine–arginine (ELR) chemokines LIX, KC and MIP-2 were all shown to be increased after myocardial I/R both at the mRNA and protein levels and acted as potent chemoattractants for neutrophil infiltration [9]. IL-37 significantly suppressed LIX and KC, but not MIP-2 expression in the ischaemic myocardium (Fig. 4d,e). Because LIX was obviously suppressed by IL-37, we investigated the direct influence of IL-37 on the migration ability of neutrophils towards LIX. Treatment with IL-37 significantly inhibited the migration of neutrophils towards LIX in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4f). These results indicate that the in-vivo IL-37-mediated inhibition of neutrophils within the ischaemic myocardium in I/R mice may be due to their suppressed migration potential and the decreased expression of chemokines.

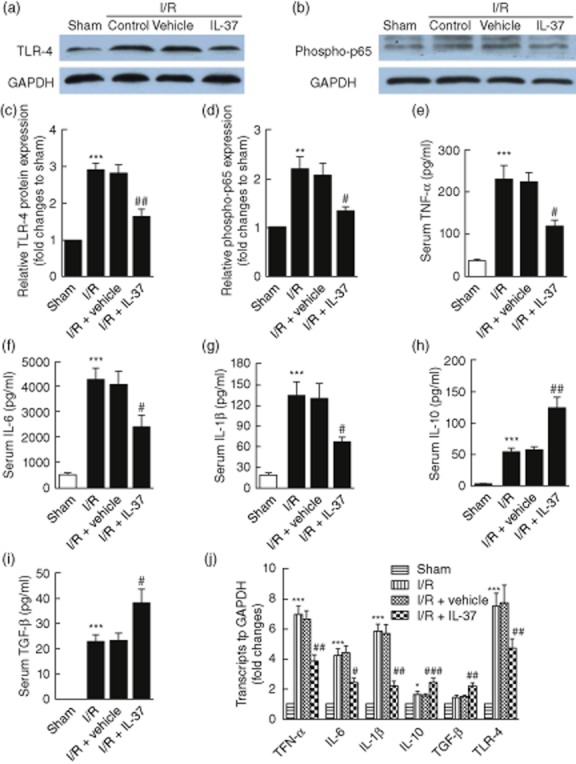

IL-37 suppresses TLR-4/NF-κB inflammation response and increases anti-inflammatory cytokines after I/R injury in mice

TLR-4 signalling activation-induced innate immune response plays an important role in myocardial I/R injury [2]. Figure 5 shows that I/R increased the levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, which were abolished by IL-37 treatment (Fig. 5e–g,j). Correspondingly, we showed that NF-κB activation was suppressed significantly in the IL-37-treated group compared with the untreated group (Fig. 5b,d), which is consistent with the results of the reduced production of inflammatory cytokines [1]. Furthermore, we examined if the inhibition of the inflammation response was due to the decreased expression of TLR-4, an upstream signalling of NF-κB [1]. We found that TLR-4 expression was inhibited significantly in IL-37-treated I/R mice compared with untreated mice (Fig. 5a,c,j).

Figure 5.

Interleukin (IL)-37 suppresses Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation and induces anti-inflammatory cytokine expression in mice myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. (a,b) Hearts were retrieved 4 h after reperfusion and the expression levels of phospho-p65 and TLR-4 were examined by Western blot analyses. (c,d) Quantitative densitometric analysis of phospho-p65 and TLR-4 with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as an internal standard (n = 6). (e–i) Serum levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α (e), IL-6 (f), IL-1β (g), IL-10 (h) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (i) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) 4 h after mouse myocardial I/R (n = 6). (j) Expression levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, TGF-β and TLR-4 in the heart tissue in different groups 4 h after mouse myocardial I/R by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) (n = 6). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001 versus sham. #P < 0·05; ##P < 0·01; ###P < 0·001 versus I/R.

Next, we investigated if the suppression of inflammation by IL-37 was associated with the increase of anti-inflammatory cytokines. To this end, we observed the expression of IL-10 and TGF-β [18,21,27]. In contrast to the inhibition of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 after myocardial I/R injury, the IL-10 expression increased significantly (Fig. 5h,j). However, the expression of TGF-β was only slightly elevated (Fig. 5i,j). Thus, IL-37 may suppress TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β expression by down-regulating TLR-4/NF-κB signalling and increasing the production of IL-10 and TGF-β, which is a distinct effect that could play a protective role in a mouse myocardial I/R injury model.

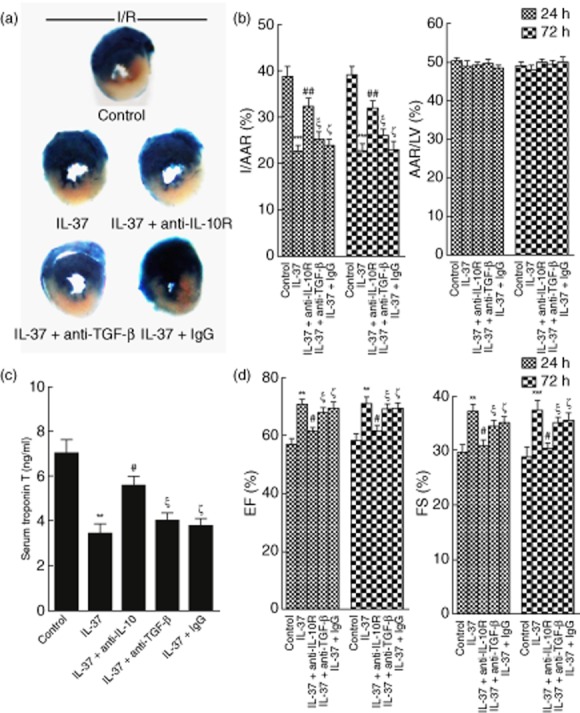

Anti-IL-10 attenuates the protective role of IL-37 in mice myocardial I/R injury

An interesting finding from this study was the obvious induction of IL-10 in IL-37-treated myocardial I/R mice. Because IL-10 has been demonstrated to play a critical protective role in I/R injury of the heart and liver [27,28], we blocked IL-10 signalling with a specific anti-IL10R mAb to observe the involvement of IL-10 in the IL-37-induced protective role in mouse myocardial I/R injury. IL-37-treated myocardial I/R mice were treated with an anti-IL-10R mAb and an additional isotype antibody for control. As shown in Fig. 6, the administration of anti-IL-10R mAb obviously attenuated the decrease of the infarction size and cardiac function mediated by IL-37 in mouse myocardial I/R injury. We further investigated the role of TGF-β in the IL-37-mediated protective role of mouse myocardial I/R injury. A similar experiment was conducted for TGF-β. However, anti-TGF-β could not abolish the protective effect of IL-37 in mouse myocardial I/R injury (Fig. 6). Taken together, IL-37 may protect the mice from myocardial I/R injury, at least in part, by increasing the IL-10 level.

Figure 6.

Interleukin (IL)-10 involved in the IL-37-mediated protective role in mice myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. IL-37-treated mice were concomitantly administered monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the IL-10 receptor (IL-10R), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β or isotype control [immunoglobulin (Ig)G], untreated I/R mice were used as a control. (a) Representative illustrations of infarct size after 24 h as stained by Evans Blue and triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC); the non-ischaemic area is indicated in blue, the area at risk (AAR) in red and the infarct area in white. (b) Quantification of infarct area/area at risk (I/AAR) and area at risk/left ventricular area (AAR/LV) 24 h and 72 h after reperfusion (n = 6). (c) Serum cardiac troponin T (cTnT) was measured in different groups 24 h after I/R (n = 6–8). (d) Ejection fraction (%EF) and fractional shortening (% FS) 24 h and 72 h after reperfusion (n = 6). **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001 versus control. #P < 0·05; ##P < 0·01 versus IL-37-treated group. ξP > 0·05 versus IL-37-treated group. ζP > 0·05 versus IL-37-treated group.

Discussion

The present study is the first to examine the role of IL-37 in mouse myocardial I/R injury. Our data demonstrated that IL-37 treatment markedly ameliorated I/R injury at the early stage, as demonstrated by reduced infarct size, cTnT level and improved cardiac function. This protective effect involved a reduction in apoptosis, oxidative stress, neutrophils infiltration and proinflammatory response, and was associated with the suppression of TLR4/NF-κB activation and an elevated level of IL-10.

Apoptosis has been regarded as an important mechanism for vast myocardial cell death in the reperfused ischaemic myocardium [26]. Apoptosis can be modulated by ROS, proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, and leucocyte accumulation [29,30]. The Bcl-2 family of proteins contain key regulators of mitochondrial membrane integrity in apoptosis that can have pro-apoptotic (e.g. Bax, Bak) and anti-apoptotic (e.g. Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) function [31]. IL-37 treatment has been shown to increase Bcl-2 expression in hepatocytes and reduce oxidant-induced hepatocyte cell death in a dose-dependent fashion in vitro [19]. In this study, we demonstrated that L-37 inhibited myocardial apoptosis in vivo, as confirmed by the change in TUNEL labelling, caspase-3 activation and the ratio of anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2) to pro-apoptotic (Bax) expression. To elucidate further the direct anti-apoptotic effect of IL-37 on cardiomyocytes, we simulated I/R injury in cardiomyocytes and found that the apoptosis ratio was reversed significantly by IL-37 treatment, which appeared to be related to the balance of expression of Bcl-2 family members. Because the inflammation response and oxidative stress change significantly when cardiomyocytes are exposed to I/R condition, these transitions jointly drive cardiomyocytes into apoptosis [29,31,32]. The mechanisms by which IL-37 directly or indirectly affects these responses to alter the apoptosis signalling pathway in myocardial I/R injury warrants further investigation.

During ischaemia reperfusion injury, the increased ROS level contributes to oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via the activation of the cytochrome c-activated caspase-3 pathway [26,33]. Strategies to interrupt the cycle of ROS production show promise for attenuating apoptosis [34]. ROS could be generated in large amounts by infiltrated leucocytes, especially activated neutrophils, in the injured myocardium [35]. Moreover, studies have revealed that IL-37 can suppress the oxidative burst of neutrophils conditioned with TNF-α in vitro, and decrease ROS production significantly during liver I/R injury [19]. Thus, we investigated the ability of IL-37 to decrease the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes by inhibiting the production of ROS after myocardial I/R injury. As indicated by DHE and lipid peroxidation, IL-37 significantly reduced the production of ROS after mouse myocardial I/R stress, and this may be related to the decreased apoptosis rate. Strategies to suppress the inflammatory response have been shown to decrease I/R injury by inhibiting apoptosis and production of ROS [1,3,30]. TNF-α, IL-18 and other proinflammatory cytokines have been reported to increase cardiomyocyte apoptosis in association with down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression and up-regulation of ROS production [36,37], and this could be abolished by IL-10 [38]. TLR-4 was reportedly involved in ROS production by interacting with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase (NADPH) oxidase 4 (NOX4) and up-regulating the expression of inducible NO synthase and cyclo-oxygenase [13,39]. This process was shown to activate NF-κB, P38 and proinflammatory factors and subsequently induce ROS production, which further exacerbated I/R injury [1,6,33,35]. In this study, we show that IL-37 could effectively suppress TLR-4/NF-κB activation and up-regulate IL-10 after I/R, which may reduce ROS production by inhibiting positive feedback of the ROS amplification loop [33,35]. Thus, IL-37 can reduce I/R-induced apoptosis significantly in vivo and vitro, probably by decreasing the proinflammatory response and ROS production.

Neutrophils are the predominant cells that aggregate in the ischaemic myocardium within the first 4 h after reperfusion to mediate direct injury via the release of toxic products, such as ROS and photolytic enzymes [8]. Therefore, strategies that hinder the infiltration of neutrophils can clearly ameliorate I/R injury. During I/R, TLR-4-mediated myocardial NF-κB activation controls KC and MCP-1 gene expression [7]. Proinflammatory factors, such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18, could enhance the production of LIX, KC, MCP-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) after myocardial I/R [30]. In agreement with these reports, inflammation suppression therapy can potentially reduce the infiltration of leucocytes and alleviate I/R injury [1,6]. IL-37 could significantly inhibit MIP-2 and KC production by LPS-stimulated hepatocytes and Kupffer cells, which was accompanied by a reduction in neutrophil infiltration during mouse liver I/R injury [19]. IL-37 also reduced leucocyte recruitment into the colonic lamina propria, which was associated with decreased inflammation in a mouse colitis model [18]. In this study, we found that IL-37 markedly decreased cardiac expression of LIX and KC, but not MIP-2, and this was accompanied by a reduction in neutrophil infiltration. For the decreased levels of LIX and KC in vivo, our experiments did not exclude the effect of IL-37 on leucocytes, myofibroblast and coronary endothelial cells, which are also involved in the inflammatory response and subsequent injury after myocardial I/R [1,9]. Furthermore, we showed that IL-37 can also directly suppress the migration ability of neutrophils towards chemokine LIX, which was most obviously changed in our model. This result is consistent with the report by Sakai et al., who revealed that IL-37 can inhibit neutrophil activation [19]. Taken together, these results revealed that IL-37 can reduce the infiltration of neutrophils into the ischaemic myocardium by inhibiting their migration ability and decreasing chemokine expression.

IL-37 undoubtedly functions as a promising beneficial compound to restrain excessive inflammatory responses [15]. In this study, we found that IL-37 can suppress TLR-4/NF-κB signalling activation after I/R injury. Studies have demonstrated that mature IL-37 translocated to the nucleus via caspase-1 and binded to phosphorylated Smad3 to form an IL-37/Smad3 complex in the perinuclear region, which affected proinflammatory gene transcription [16]. Indeed, Smad3 deficiency has been shown to result in the hyperactivation of innate immune cells, which occurs in response to TLR signalling and subsequent NF-κB activation [40]. Smad3 has also been shown to have protective effects in myocardial I/R mice and cardiomyocytes treated with growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15), a secreted member of the TGF-β superfamily [41]. IL-37 can also function by combining with TIR8 [single immunoglobulin (Ig) IL-1-related receptor (SIGIRR)] on the cell membrane in PBMC, macrophages and dendritic cells [42,43], which mediates the suppression of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) [p38 and extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK)] activation and TLR-4/NF-κB signalling activation by inhibiting the recruitment of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) and TNF receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) [44–46]. We therefore speculate that IL-37 may function in several ways in the I/R model, including suppressing the effect of IL-18 through combining with IL-18BP [17,43], inhibiting TLR-4/NF-κB activation through extracellular mechanisms via TIR8 (SIGIRR), as well as by intracellular mechanisms via Smad3 and p38 [16,42,43]. This requires further investigation using chimeric IL-18R alpha or SIGIRR/TIR8 knock-out mice.

Finally, we observed a significant increase in the level of IL-10 but a relatively smaller increase in TGF-β, and the elevated IL-10 level was associated partly with the protective role of IL-37 treatment in mice with myocardial I/R injury. Clinical researches have showed that increased proinflammatory cytokine levels, such as IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP), correlated with deterioration of LV systolic function and manifested an independent predictor of LV systolic dysfunction in myocardial ischaemia (MI) patients. Conversely, maintenance of a boosted level of IL-10 seemed to be prognostically favourable [47]. IL-10 is expressed and secreted by a variety of cell types such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), B cells, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells and natural killer cells [48,49]. In contrast with the role of IL-18 in myocardial I/R injury [36], as proved in the IL-10-deficient mice by Yang et al., endogenous production of IL-10 during myocardial I/R played a key role in determination of the outcome by suppressing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, accompanied by decreased neutrophil infiltration and activation [27], and studies have shown that, using some ingenious methods, IL-10 levels in I/R myocardium can be regulated [50–52]. Although, currently, no research has demonstrated that IL-37 has a direct effect on Treg cells and B cells, it has been shown to maintain immature dendritic cells and suppress macrophage differentiation towards the M1 subtype by significantly decreasing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [16,42], which leads to increased production of IL-10 [48]. In a dextran sodium sulphate (DSS)-induced mouse colitis model, IL-37 showed significantly increased levels of IL-10, although this was not responsible for the IL-37-induced protective role in that model [18]. This disparity with our model may be due to the difference in severity of the local and systemic inflammatory response occurring between the two models. Indeed, there was more effective dampening of TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokine levels compared to supplementing with IL-10 in that model in contrast to ours.

In summary, IL-37 treatment can reduce myocardial I/R injury in mice, which is associated with the ability of IL-37 to suppress the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and the infiltration of neutrophils, accompanied by decreased cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ROS generation. In addition, IL-37 preserves the balance of the inflammation response by inhibiting TLR-4/NF-κB activation and increasing IL-10 during mouse myocardial I/R injury, and the protective effect of IL-37 is associated in part with elevated IL-10. These data imply that IL-37 could be a promising therapeutic medium for myocardial I/R injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81070237 to Q.Z., 81270354 to Q.Z., 81100084 to M.C and 81160045 to Q.J.).

Disclosures

None declared.

Author contributions

B. W., K. M., Q. J. and Q. Z. conceived and designed the experiments. B. W., K. M., X. Z., K. Y. and Y. L. performed the experiments. B. W., Q. J., M. C., Y. Z. and Q. Z. analysed the data. C. C., Y. C. Z., Z. Z., W. Z., X. M. and H. T. contributed the materials, reagents and analysis tools. B. W. and Q. Z. wrote the paper.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) primer sequences.

References

- 1.Arslan F, de Kleijn DP, Pasterkamp G. Innate immune signaling in cardiac ischemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:292–300. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Si R, Feng Y, et al. Myocardial ischemia activates an injurious innate immune signaling via cardiac heat shock protein 60 and Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:31308–31319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.246124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oyama J, Blais C, Jr, Liu X, et al. Reduced myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury in toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice. Circulation. 2004;109:784–789. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112575.66565.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmers L, Pasterkamp G, de Hoog VC, Arslan F, Appelman Y, de Kleijn DP. The innate immune response in reperfused myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:276–283. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd JH, Mathur S, Wang Y, Bateman RM, Walley KR. Toll-like receptor stimulation in cardiomyoctes decreases contractility and initiates an NF-kappaB dependent inflammatory response. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science. 2003;300:1524–1525. doi: 10.1126/science.1085536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ao L, Zou N, Cleveland JC, Jr, Fullerton DA, Meng X. Myocardial TLR4 is a determinant of neutrophil infiltration after global myocardial ischemia: mediating KC and MCP-1 expression induced by extracellular HSC70. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H21–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00292.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaminski KA, Bonda TA, Korecki J, Musial WJ. Oxidative stress and neutrophil activation – the two keystones of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int J Cardiol. 2002;86:41–59. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frangogiannis NG. Chemokines in ischemia and reperfusion. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:738–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimamoto A, Chong AJ, Yada M, et al. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 4 with eritoran attenuates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2006;114:I270–274. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Z, Hu Y, Wu W, et al. The TIR/BB-loop mimetic AS-1 protects the myocardium from ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:442–451. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moss NC, Stansfield WE, Willis MS, Tang RH, Selzman CH. IKKbeta inhibition attenuates myocardial injury and dysfunction following acute ischemia–reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2248–2253. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00776.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsung A, Klune JR, Zhang X, et al. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4 dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2913–2923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan J, Li Y, Levy RM, et al. Hemorrhagic shock induces NAD(P)H oxidase activation in neutrophils: role of HMGB1-TLR4 signaling. J Immunol. 2007;178:6573–6580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tete S, Tripodi D, Rosati M, et al. IL-37 (IL-1F7) the newest anti-inflammatory cytokine which suppresses immune responses and inflammation. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:31–38. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nold MF, Nold-Petry CA, Zepp JA, Palmer BE, Bufler P, Dinarello CA. IL-37 is a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bufler P, Gamboni-Robertson F, Azam T, Kim SH, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 homologues IL-1F7b and IL-18 contain functional mRNA instability elements within the coding region responsive to lipopolysaccharide. Biochem J. 2004;381:503–510. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNamee EN, Masterson JC, Jedlicka P, et al. Interleukin 37 expression protects mice from colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16711–16716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111982108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakai N, Van Sweringen HL, Belizaire RM, et al. Interleukin-37 reduces liver inflammatory injury via effects on hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1609–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji QW, Zeng QT, Huang Y, et al. Elevated plasma IL-37, IL-18 and IL-18BP concentrations in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/165742. Article ID 165742, 9 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dandapat A, Hu CP, Li D, et al. Overexpression of TGFbeta1 by adeno-associated virus type-2 vector protects myocardium from ischemia–reperfusion injury. Gene Ther. 2008;15:415–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsushima S, Kuroda J, Ago T, et al. Broad suppression of NADPH oxidase activity exacerbates ischemia/reperfusion injury through inadvertent downregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Circ Res. 2013;112:1135–1149. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao YH, Xia N, Zhou SF, et al. Interleukin-17A contributes to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating cardiomyocyte apoptosis and neutrophil infiltration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh YB, Ahn M, Lee SM, et al. Inhibition of Janus activated kinase-3 protects against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. Exp Mol Med. 2013;45:e23. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou SL, Dai Z, Zhou ZJ, et al. Overexpression of CXCL5 mediates neutrophil infiltration and indicates poor prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:2242–2254. doi: 10.1002/hep.25907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fliss H, Gattinger D. Apoptosis in ischemic and reperfused rat myocardium. Circ Res. 1996;79:949–956. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Z, Zingarelli B, Szabo C. Crucial role of endogenous interleukin-10 production in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2000;101:1019–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ke B, Shen XD, Tsuchihashi S, et al. Viral interleukin-10 gene transfer prevents liver ischemia–reperfusion injury: toll-like receptor-4 and heme oxygenase-1 signaling in innate and adaptive immunity. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:355–366. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Gottlieb RA. The interplay between pro-death and pro-survival signaling pathways in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: apoptosis meets autophagy. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2006;20:445–462. doi: 10.1007/s10557-006-0583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion – from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding HS, Yang J, Chen P, Bo SQ, Ding JW, Yu QQ. The HMGB1–TLR4 axis contributes to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Gene. 2013;527:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang PM, Haunstetter A, Aoki H, Usheva A, Izumo S. Morphological and molecular characterization of adult cardiomyocyte apoptosis during hypoxia and reoxygenation. Circ Res. 2000;87:118–125. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker LB. New concepts in reactive oxygen species and cardiovascular reperfusion physiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Y, Guan Y, Duan J, et al. Cardioprotective effect of Danshensu against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and inhibits apoptosis of H9c2 cardiomyocytes via Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;699:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raedschelders K, Ansley DM, Chen DD. The cellular and molecular origin of reactive oxygen species generation during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:230–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang M, Markel TA, Meldrum DR. Interleukin 18 in the heart. Shock. 2008;30:3–10. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318160f215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkatachalam K, Prabhu SD, Reddy VS, Boylston WH, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. Neutralization of interleukin-18 ameliorates ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial injury. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7853–7865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808824200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaur K, Sharma AK, Dhingra S, Singal PK. Interplay of TNF-alpha and IL-10 in regulating oxidative stress in isolated adult cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhee SH, Hwang D. Murine TOLL-like receptor 4 confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness as determined by activation of NF kappa B and expression of the inducible cyclooxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34035–34040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCartney-Francis N, Jin W, Wahl SM. Aberrant Toll receptor expression and endotoxin hypersensitivity in mice lacking a functional TGF-beta 1 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2004;172:3814–3821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ago T, Sadoshima J. GDF15, a cardioprotective TGF-beta superfamily protein. Circ Res. 2006;98:294–297. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207919.83894.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li SZ, Hong J, Nold MF, et al. Recombinant IL-37 inhibits LPS induced inflammation in a SIGIRR-and MAPK-dependent manner [Abstract] Cytokine. 2013;63:281. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nold MF, Nold CA, Lo C, et al. Interleukin 37 employs the IL-1 family inhibitory receptor SIGIRR and the alpha chain of the IL-18 receptor to suppress innate immunity [Abstract] Cytokine. 2013;63:287. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garlanda C, Anders HJ, Mantovani A. TIR8/SIGIRR: an IL-1R/TLR family member with regulatory functions in inflammation and T cell polarization. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. p38-Dependent marking of inflammatory genes for increased NF-kappa B recruitment. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:69–75. doi: 10.1038/ni748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang X, Hazlett LD, Du W, Barrett RP. SIGIRR promotes resistance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis by down-regulating type-1 immunity and IL-1R1 and TLR4 signaling. J Immunol. 2006;177:548–556. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ammirati E, Cannistraci CV, Cristell NA, et al. Identification and predictive value of interleukin-6+ interleukin-10+ and interleukin-6-interleukin-10+ cytokine patterns in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;111:1336–1348. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.262477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ammirati E, Cianflone D, Banfi M, et al. Circulating CD4+CD25hiCD127lo regulatory T-Cell levels do not reflect the extent or severity of carotid and coronary atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1832–1841. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burchfield JS, Iwasaki M, Koyanagi M, et al. Interleukin-10 from transplanted bone marrow mononuclear cells contributes to cardiac protection after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2008;103:203–211. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, de la Rosa A, Vargas M, Ferrer J, Garcia M. Role of endogenous interleukin-10 production and lipid peroxidation in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, interleukin-10 and primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol. 2005;99:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Cheng X, Liao YH, et al. Simvastatin regulates myocardial cytokine expression and improves ventricular remodeling in rats after acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-6893-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) primer sequences.