Abstract

Background

Smokers with greater knowledge of the health effects of smoking are more likely to quit and remain abstinent. Australia has communicated the causal association of smoking and blindness since the late 1990s. In March 2007, Australia became the first country to include a pictorial warning label on cigarette packages with the message that smoking causes blindness. The current study tested the hypothesis that the introduction of this warning label increased smokers’ knowledge of this important health effect.

Methods

Six waves of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey were conducted, as a telephone survey of 17,472 adult smokers in Australia, Canada, United Kingdom and the United States, with three waves before and three waves after the blindness health warning was introduced in Australia. The survey measured adult smokers’ knowledge that smoking causes blindness.

Results

Australian smokers were significantly more likely to report that smoking causes blindness, compared to Canadian, UK and US smokers, where there were neither health campaigns nor health warnings labels about blindness. After the introduction of the blindness warning, Australian smokers were more likely than before the blindness warning to report that they know that smoking causes blindness (62 versus 49 per cent; OR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.03, 2.76, p = 0.04). In Australia, smokers aged over 55 years were less likely than those aged 18 to 24 to report that smoking causes blindness (OR = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.29, 0.62, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

While more smokers report that smoking causes blindness in Australia compared to other countries, which have not had national social marketing campaigns, further gains in knowledge were found after pictorial warning labels were introduced in Australia. Findings suggest there is still a need to educate the public about the causal association of smoking and blindness. More education may be needed to redress the knowledge gap in older Australian smokers as the incidence of age-related macular degeneration increases with age.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, cessation, health education, public health, smoking

Between 1950 and 2008, an estimated 900,000 Australians died prematurely because they smoked. It is expected that the toll will exceed one million within the next decade.1 Despite reductions in the prevalence of tobacco use in the last 30 years, smoking is still the largest preventable cause of death and disease in the country with approximately 19 per cent of the population smoking daily in 2007–8 (over three million people).2 Tobacco smoking costs the Australian health care system more than $30 billion a year.3 Smoking also causes numerous health conditions, including certain ocular diseases that do not result in death but do greatly impact quality of life.4–6 Smoking causes or contributes to approximately 20 per cent of all new cases of blindness in Australia for people over the age of 50.7 The most common eye disease causally linked to smoking is age-related macular degeneration (AMD). AMD is the leading primary cause of blindness in Australia8 with an estimated 150,000 Australians having AMD as of 20049 and approximately 17,700 new cases of wet macular degeneration, reported annually.10

Perceived health risk plays an important role in initiating and quitting smoking.11 Smokers with a high knowledge of the health effects of smoking are more likely to quit and remain abstinent.12,13 Australia is one of only a few jurisdictions in the world, where public and non-governmental sectors are working toward increasing public knowledge about the risk of smoking on ocular health. Australia’s National Tobacco Campaign, launched in 1997, has included numerous health promotion initiatives, including a television advertisement that linked smoking and ‘loss of eye sight’ starting in 1998.14 The advertisement explained how smoking can damage blood vessels in the back of the eye, leading to visual loss. The ‘eye’ advertisement has been run intermittently since 1998 and is credited with encouraging more Australian smokers to call the national Quitline than any other message about the health effects from smoking.15 This suggests that the message that ‘smoking causes blindness’ is effective at increasing interest in cessation.

A 2011 study16 reported that a low proportion of adult smokers from Canada (13 per cent), the United States (10 per cent) and the United Kingdom (10 per cent) believed that smoking can cause blindness. In contrast, 47 per cent of Australian daily smokers believed that smoking causes blindness. The study noted that Australia was the only country during the sampling period to have national social marketing campaigns about smoking and its effects on ocular health. This finding suggests that social marketing campaigns likely contributed to higher knowledge among smokers about the causal links between smoking and blindness; however, even with years of government-sponsored social marketing, less than half of the Australian smokers reported that they were aware of the connection between smoking and blindness.

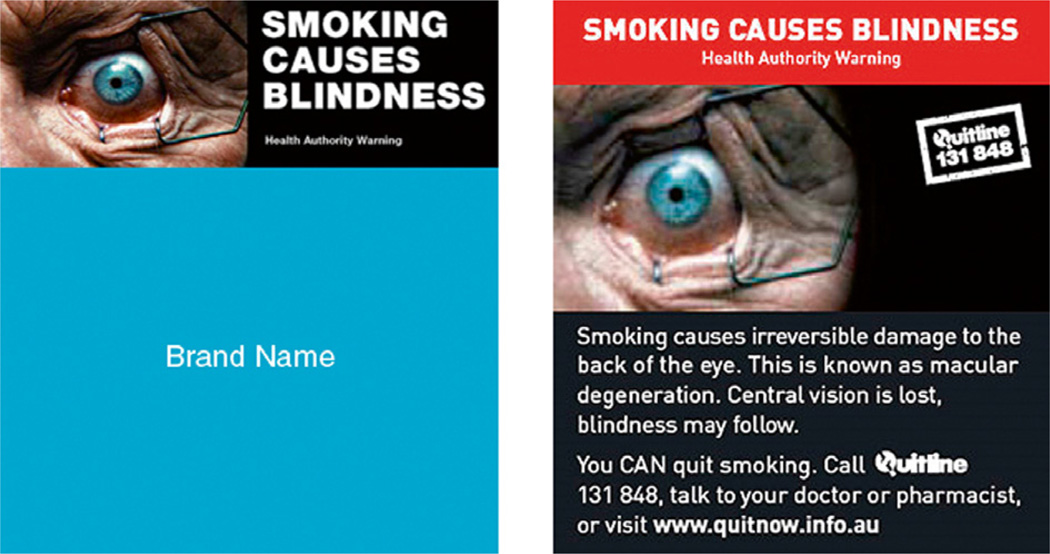

The Australian Commonwealth government has required tobacco manufacturers to include textual health warnings on cigarette packages since 1973.17 In March 2006, new pictorial health warnings (pictures and written warnings) were required on most domestic and imported tobacco product packaging.18 The intended purpose of these warning labels was to increase knowledge of the health effects relating to smoking, encourage smoking cessation and discourage smoking uptake or relapse.17 One of the 14 warning labels, commonly referred to as the ‘eye’, included the written warning, ‘Smoking causes blindness’. The graphic used was a still from the 1998 television advertisement. When these graphic warning labels were evaluated in discussion groups with smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers for the Australian Department of Health and Ageing, ‘the eye’ image dominated responses. The image was described as ‘grotesque’ and was considered to have high emotional impact (Figure 1).17

Figure 1.

Australian pictorial and textual cigarette warning label (front and back) ‘Smoking Causes Blindness’, required to be in circulation on packs in March 2007; Source: www.quitnow.info.au

The current study sought to examine how the introduction of the ‘Smoking causes blindness’ warning label may have impacted smokers’ knowledge of this health effect in Australia and to compare this with the knowledge of smokers in comparable countries, where there were no similar warning labels on cigarette packs. This study also sought to understand if personal characteristics, such as sex or socio-economic status, were related to knowledge about smoking causing blindness. Data used in this study were collected between 2004 and 2011, with sampling taking place both before and after the introduction of the Australian warning label.

The study analysed data from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC) Four Country Survey conducted in Australia (AU), Canada (CA), United Kingdom (UK) and United States (US). Since 2002, the ITC Four Country Survey has collected data from nationally representative samples of adult smokers (18 years and older), approximately annually. Since 2004, Wave 3, the survey has included a question to assess smokers’ knowledge of blindness and smoking. During the present study period (2004–2011), there was no national social marketing campaign that explained the causal link between smoking and ‘blindness’ in Canada, UK or the US. In 2003 and 2008, the UK introduced new warning labels; however, only Australia had a tobacco product warning label that communicated health knowledge about smoking and ocular health.

METHODS

Detailed information on the procedures used in the ITC Four Country Survey have been published.19–22 In brief, the survey is conducted using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) software and is completed in two calls: a 10-minute recruitment call, which is followed approximately one week later by a 40-minute main survey. To increase recruitment rates, participants are mailed a compensation equivalent to $10 AUD before completing the main survey. The survey is longitudinal; however, each wave includes new respondents recruited to replace those lost to follow-up. In this study, the results of three survey waves collected before the introduction of the Australian eye warning label (between June 2004 and February 2007), were compared with the results of three survey waves collected after its introduction (between September 2007 and May 2011).

Sample

Participants in the ITC Four Country Survey are 18 years or older, have smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lives and at least once in the past 30 days. The analysis in this report was limited to respondents answering the blindness knowledge question for their first time. This was done to avoid measuring respondents’ accumulated knowledge that may occur as a result of participation in the longitudinal survey. Participants recruited in 2002 and 2003 were first asked questions about blindness in 2004 (Wave 3). Combining respondents from 2004–2011 (Wave 3 and replenishment samples in Waves 4–8) resulted in a sample size of 17,472 smokers, nationally representative of these countries (Australia, n = 4,035; Canada, n = 4,304; UK, n = 4,089; US, n = 5,044). The number of respondents who were surveyed pre-introduction of the warning labels differed from the number of respondents post-introduction. The pre-period was larger, as it included all respondents from Wave 3 and replenishment samples from Waves 4 and 5 (June 2004–February 2007). The post-introduction sample included respondents recruited through replenishment during Waves 6–8 (September 2007– June 2011). Further details about the sample and data collection dates are presented in Tables 1A and 1B.

Table 1.

| A Description of survey sample and weighted population estimates for respondents of International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey before the introduction of blindness warning labels in Australia. June 2004–December 2004 = Wave 3; October 2005–January 2006 = Wave 4; October 2006–February 2007 = Wave 5. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia (n = 3,151) |

Canada (n = 3,221) |

UK (n = 3,196) |

US (n = 3,575) |

|||||

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1,454 | 54.8 (52.8, 56.7) | 1,426 | 53.0 (51.17, 55.0) | 1,393 | 51.0 (48.9, 53.0) | 1,484 | 53.6 (51.7, 55.5) |

| Female | 1,697 | 45.3 (43.3, 47.2) | 1,795 | 47.0 (45.1, 48.9) | 1,803 | 49.0 (47.0, 51.0) | 2,091 | 46.4 (44.6, 48.3) |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18 to 24 | 391 | 15.2 (13.7, 16.8) | 370 | 14.0 (12.6, 15.6) | 223 | 14.2 (12.4, 16.3) | 350 | 14.5 (13.1, 16.1) |

| 25 to 39 | 1,078 | 35.7 (33.8, 37.7) | 977 | 32.4 (30.5, 34.3) | 942 | 32.7 (30.8, 34.7) | 899 | 31.5 (29.6, 33.3) |

| 40 to 54 | 1,143 | 33.0 (31.1, 34.8) | 1,232 | 35.9 (34.0, 37.7) | 1,138 | 30.4 (28.7, 32.2) | 1,365 | 35.5 (33.7, 37.3) |

| 55+ | 539 | 16.2 (14.8, 17.8) | 642 | 17.8 (16.4, 19.2) | 893 | 22.7 (21.2, 24.3) | 961 | 18.6 (17.4, 19.9) |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| Low education | 1,997 | 63.9 (62.0, 65.9) | 1,507 | 47.2 (45.3, 49.2) | 1,936 | 58.9 (56.8, 60.9) | 1,600 | 46.6 (44.7, 48.5) |

| Moderate education | 692 | 22.0 (20.3, 23.7) | 1,207 | 37.6 (35.7, 39.5) | 800 | 27.6 (25.8, 29.6) | 1,356 | 37.6 (35.8, 39.5) |

| High education | 456 | 14.1 (12.8, 15.5) | 500 | 15.2 (14.0, 16.6) | 430 | 13.5 (12.1, 14.9) | 613 | 15.8 (14.5, 17.2) |

| Household income | ||||||||

| Low income | 901 | 26.4 (24.7, 28.2) | 875 | 25.7 (24.1, 27.4) | 1,001 | 28.4 (26.7, 30.2) | 1,308 | 35.0 (33.2, 36.8) |

| Middle income | 1,016 | 32.5 (30.6, 34.5) | 1,115 | 35.0 (33.2, 36.9) | 1,028 | 32.7 (30.8, 34.7) | 1,240 | 35.5 (33.6, 37.3) |

| High income | 1,036 | 34.6 (32.6, 36.5) | 997 | 32.3 (30.5, 34.2) | 878 | 30.7 (28.7, 32.7) | 829 | 24.1 (22.6, 25.8) |

| Refused | 198 | 6.5 (5.6, 7.6) | 232 | 7.0 (6.1, 8.0) | 289 | 8.2 (7.2, 9.4) | 198 | 5.4 (4.6, 6.4) |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) | ||||||||

| Mean HSI (95% CI) | 2,855 | 2.65 (2.59, 2.71) | 2,966 | 2.67 (2.61, 2.72) | 2,922 | 2.56 (2.51, 2.62) | 3,352 | 2.81 (2.75, 2.86) |

| B Description of survey sample and weighted population estimates for respondents of International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey after introduction of blindness warning labels in Australia (2007–2011). September 2007–February 2008 = Wave 6; October 2008–July 2009 = Wave 7; July 2010 to June 2011 = Wave 8. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia (n = 884) |

Canada (n = 1,083) |

UK (n = 893) |

US (n = 1,469) |

|||||

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 419 | 53.9 (50.1, 57.7) | 551 | 53.2 (49.6, 56.8) | 404 | 50.9 (47.0, 54.8) | 761 | 55.0 (51.6, 58.3) |

| Female | 465 | 46.1 (42.3, 50.0) | 532 | 46.8 (43.2, 50.4) | 489 | 49.1 (45.3, 53.0) | 708 | 45.0 (41.7, 48.4) |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18 to 24 | 71 | 12.2 (9.5, 15.3) | 65 | 11.4 (8.7, 14.8) | 69 | 13.4 (10.6, 16.8) | 76 | 11.8 (9.3, 14.9) |

| 25 to 39 | 277 | 37.5 (33.7, 41.4) | 284 | 31.6 (28.3, 35.2) | 245 | 34.4 (30.6, 38.3) | 248 | 30.65 (27.2, 34.3) |

| 40 to 54 | 330 | 31.8 (28.5, 35.4) | 411 | 33.8 (30.6, 37.2) | 290 | 29.4 (26.1, 32.8) | 569 | 33.9 (30.9, 36.9) |

| 55+ | 206 | 18.5 (15.9, 21.5) | 323 | 23.2 (20.6, 26.0) | 289 | 22.9 (20.2, 25.8) | 576 | 23.7 (21.4, 26.1) |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| Low education | 507 | 55.7 (51.8, 59.5) | 537 | 49.5 (45.9, 53.2) | 505 | 56.3 (52.4, 60.1) | 663 | 45.2 (41.8, 48.7) |

| Moderate education | 243 | 28.6 (25.2, 32.3) | 347 | 33.1 (29.7, 36.6) | 241 | 27.4 (24.1, 31.0) | 513 | 36.0 (32.8, 39.3) |

| High education | 133 | 15.7 (13.1, 18.8) | 192 | 17.4 (14.9, 20.2) | 146 | 16.3 (13.5, 19.4) | 289 | 18.8 (16.2, 21.7) |

| Household income | ||||||||

| Low income | 193 | 17.9 (15.3, 20.8) | 273 | 21.9 (19.3, 24.8) | 270 | 26.2 (23.1, 29.5) | 500 | 30.9 (28.0, 34.1) |

| Middle income | 269 | 32.1 (28.5, 35.9) | 354 | 33.4 (30.0, 36.9) | 259 | 29.9 (26.5, 33.6) | 437 | 30.1 (27.0, 33.4) |

| High income | 366 | 44.6 (40.8, 48.5) | 348 | 35.6 (32.2, 39.1) | 259 | 33.0 (29.4, 36.8) | 383 | 29.0 (25.9, 32.3) |

| Refused | 56 | 5.4 (4.0, 7.2) | 108 | 9.1 (7.4, 11.3) | 105 | 10.9 (8.8, 13.5) | 149 | 10.0 (8.2, 12.2) |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index (HIS) | ||||||||

| Mean HSI (95% CI) | 864 | 2.79 (2.68, 2.90) | 1,060 | 2.84 (2.75, 2.94) | 878 | 2.65 (2.56, 2.75) | 1,428 | 2.84 (2.76, 2.92) |

Note: The survey sample size (n) figures are unweighted while the population estimate percents and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are weighted.

Australian graphic warning label introduction—’Smoking causes blindness’

Two sets of seven graphic health warnings (Set A and Set B) appeared on cigarette packs in Australia. Tobacco manufacturers were required to ensure each set of seven warnings was printed on an approximately equal number of each product type for each rotation period.23 Set A warning labels were first printed on cigarette packs from March 2006 to February 2007. The ‘eye’ warning was part of Set B; labels from Set B were required to be on cigarette packages from March 2007 to February 2008. Labels from Sets A and B were similarly alternated on an annual basis. A transition period was permitted between sets from November to February of the cycle, so it was possible that the eye label first appeared in some parts of Australia as early as November 2006. For the analysis in this paper, we considered March 1, 2007 as the official time when the label was present in Australia as that date represented a time when all cigarette packs in the country were required to have only Set B labels.

Measures

DEMOGRAPHICS AND SMOKING HISTORY

In the present study, the following socio-demographic variables were of interest: age (18 to 24, 25 to 39, 40 to 54 and 55 and older), sex, income and education levels. Income classifications were ‘low’, ‘moderate’ or ‘high’. In the US, Canadian and Australian samples, these annual income categories represented: under $30,000, $30,000 to $59,999 and $60,000 and over. The comparable annual UK income categories were: £15,000 or under, £15,001 to £30,000 and £30,001 and over. Income also included a ‘refused’ category, as commonly this is a large proportion of a sample. Education was classified as ‘low’ (less than high school), ‘moderate’, (high school) or ‘high’ (some university or a university/college degree). Additionally, a standard measure of tobacco addiction (the heaviness of smoking index or HSI, a continuous variable) was also measured.24

KNOWLEDGE THAT SMOKING CAUSES BLINDNESS

Respondents were asked a set of questions prefaced by, ‘I am going to read you a list of health effects and diseases that may or may not be caused by smoking cigarettes. Based on what you know or believe.’ This statement was followed by possible health effects, including, ‘does smoking cause blindness?’ The response options were: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Refused’ or ‘Don’t know.’ Respondents reporting ‘refused’ were classified as missing and as ‘no’ if responding ‘don’t know’. Responses are presented for respondents who answered the knowledge question before the eye warning label (surveyed between June 2004 and February 2007) and after the eye warning label (September 2007 to May 2011).

Analysis

Frequencies with 95% confidence intervals were run to compute country-specific proportions of smokers responding in the affirmative to the main outcome regarding knowledge of smoking causing blindness for both study time points (pre- and post-introduction of the Australian eye warning label). Cross sectional survey-weights were used in all calculations.21,22 One change of interest was the country-specific change in proportions in the pre/post-introduction of the warning label. This change was assessed using chi-square tests (α = 0.05 level of significance) independently for each country. A secondary change of interest was the specific time of change, which was hypothesised to have occurred in Australia. To better capture the latter, chi-square tests were run on proportions of each wave, comparing a wave to proportions of the wave directly preceding it.

A multivariate logistic regression was run to better understand smoker characteristics predicting the likelihood of knowledge of the link between smoking and blindness. Models pooled country-specific data across all waves of recruitment. Model predictors included age (categorical), sex (binary), income (categorical), education (categorical), HSI (continuous) and a binary before and after ‘eye’ warning label variable. The latter was computed as follows with respondents surveyed between June 2004 to February 2007 (Waves 3 to 5), labelled as pre and respondents surveyed between September 2007–June 2011 (Waves 6 to 8) as post. The final models also included interactions between all demographic variables and the pre/post-variable and were run independently for each country to avoid confounding the high knowledge rates in Australia as compared with the other three countries. Presented regression models are weighted; however, results are similar to unweighted models, an indication of the robustness of the model fit. All analyses were run in STATA 10.0 SE.25

RESULTS

The sample of smokers from the pre-introduction of the ‘eye’ warning label on cigarette packages in Australia (June 2004 to February 2007), included 13,143 respondents (Australia: n = 3,151, Canada: n = 3,221, UK: n = 3,196 and US: n = 3,575,). The sample of smokers from the post-introduction of the ‘eye’ warning label surveyed September 2007 to May 2011 included 4,329 respondents (Australia: n = 884, Canada: n = 1,083, UK: n = 893 and US: n = 1,469). Full sample characteristics for the pre/post-introduction of the warning label can be found in Tables 1A and 1B.

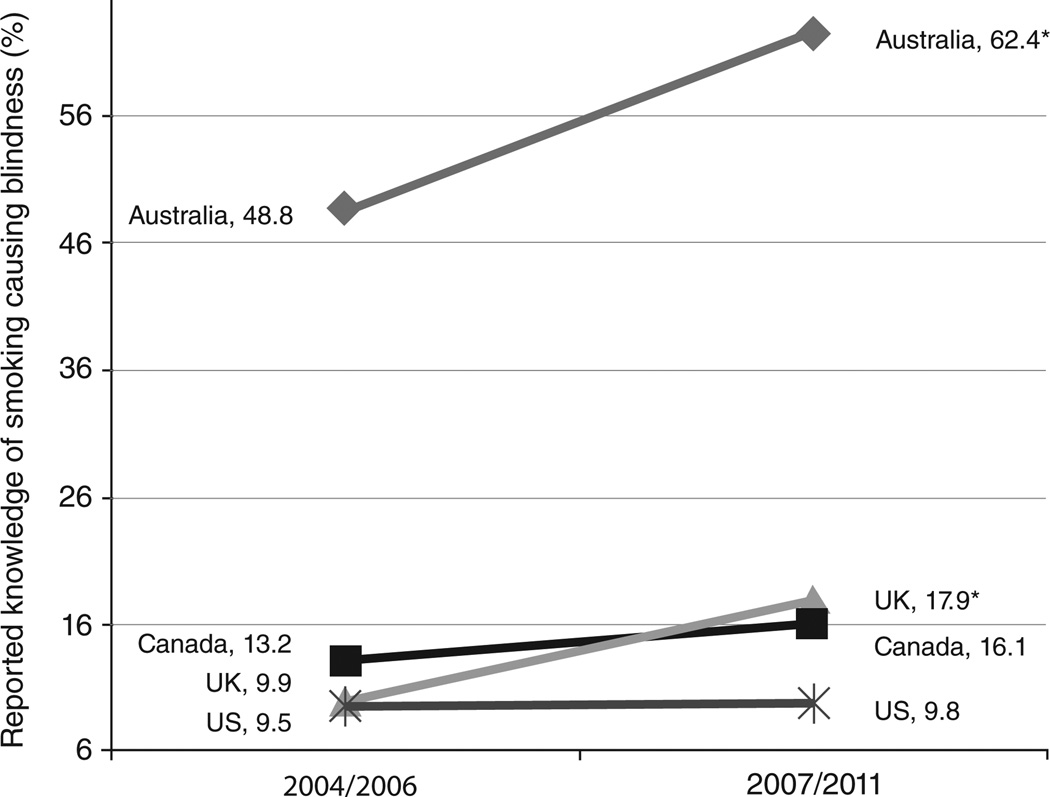

Figure 2 presents country-specific changes in proportions of smokers reporting that smoking causes blindness. Proportions are given for both before and after introduction of the ‘eye’ warning label in Australia. Prior to the introduction of the warning label, less than half of Australian smokers (48.8 per cent, 95% CI: 46.8, 50.8) reported that they believed that smoking causes blindness. This proportion significantly increased (χ2 = 43.04, p < 0.001) to 62.4 per cent (95% CI: 58.6, 66.0) after the warning labels were introduced in March 2007.

Figure 2.

Changes in reported knowledge of the causal association between smoking and ‘blindness’, by country (2004/2006–2007/2011)

*Indicates country-specific significant change in proportion between 2004/2006 and 2007/2011 using χ2 test α= 0.05 significance level

In Canada, UK and the US, the proportions of adult smokers reporting the belief that smoking causes blindness were significantly lower compared with both Australian samples before and after the introduction of the Australian warning label. In Canada and the US, there was no significant change in proportions (p > 0.05 for χ2 tests) between pre- and post-values, with knowledge topping out at 16.1 per cent (95% CI: 13.4, 19.2) and 9.8 per cent (95% CI: 7.8, 12.2), respectively, in the post period (2007 to 2011). In the UK, the proportion of adult smokers reporting that smoking causes blindness significantly increased (χ2 = 61.67, p < 0.001) from approximately 9.9 per cent (95% CI: 8.8, 11.3) to 17.9 per cent (95% CI: 15.8, 21.9) between the pre- and post-study periods. Looking at the proportion of UK smokers reporting knowledge of blindness and smoking year over year, a significant change took place between the sampling period of June–December 2004 (Wave 3) and October 2005–January 2006 (Wave 4); knowledge went from 6.9 per cent (95% CI: 5.7, 8.5) to 16.1 per cent (95% CI: 12.8, 20.0). Knowledge of smoking causing blindness remained similar throughout the later sampling periods in the UK.

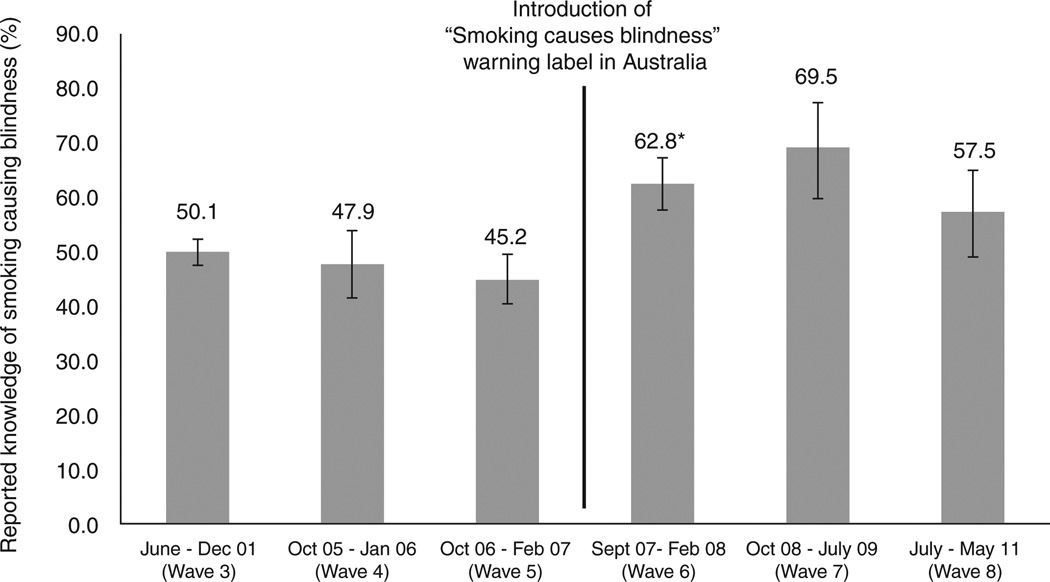

Year by year changes in proportions of smokers reporting knowledge of blindness and smoking in Australia are presented in Figure 3. A significant change (χ2 = 14.14, p < 0.001) in proportions reporting knowledge occurred between the Wave 5 sampling period (between October 2006 and February 2007) and Wave 6 (September 2007 to February 2008), coinciding with the introduction of the ‘eye’ warning label. Knowledge among Australian smokers remained high through the subsequent sampling periods between 2007 and 2011 (Waves 7 and 8), peaking at approximately 70 per cent.

Figure 3.

The percentage of Australian adult smokers knowing that smoking causes blindness across six waves of the International Tobacco Control Australia Survey (2004 to 2011)

*Indicates significant change in proportion as compared to the preceding wave using χ2 test α= 0.05 significance level

Table 2 presents the findings from the multivariate logistic regression model conducted to examine if demographic and smoking-specific characteristics among adult Australian smokers may be associated with knowledge of smoking causing blindness across all years.

Table 2.

Australian smokers’ likelihood of reporting knowledge that smoking causes blindness—(International Tobacco Control Australia) 2004–2011

| Predictors—Australia | Odds ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Before (Waves 1–5) | Base level | |

| After (Waves 6–8) | 1.68 (1.03, 2.76) | 0.038* |

| Sex | ||

| Female | Base level | |

| Male | 1.08 (0.78, 1.51) | 0.644 |

| Age group | ||

| 18 to 24 | Base level | |

| 25 to 39 | 0.82 (0.53, 1.28) | 0.388 |

| 40 to 54 | 0.70 (0.53, 0.93) | 0.015* |

| 55+ | 0.43 (0.29, 0.62) | <0.001* |

| Income | ||

| Low income | Base level | |

| Moderate income | 1.25 (0.96, 1.63) | 0.095 |

| High income | 0.86 (0.68, 1.10) | 0.224 |

| No answer | 1.05 (0.72, 1.53) | 0.806 |

| Education | ||

| Low education | Base level | |

| Moderate education | 1.10 (0.88, 1.37) | 0.392 |

| High education | 1.33 (0.78, 2.26) | 0.292 |

| Dependence | ||

| Increasing HSI Score | 0.99 (0.85, 1.15) | 0.89 |

Indicates a statistically significant finding using an α = 0.05 significance level

Australian smokers in the period post-introduction of the ‘eye’ warning label (September 2007 to May 2011) were 1.68 times as likely (95% CI: 1.03, 2.76, p = 0.038) than Australian smokers in the pre period (June 2004 to February 2007) to report knowledge of the smoking and blindness link (Table 2). In Australia, increasing age was associated with a lower likelihood of knowledge with ages 40 to 54 (odds ratio: 0.70, CI: 0.53, 0.93, p = 0.015) and over 55 years (OR: 0.43, 0.29, 0.62, p < 0.001) significantly less likely than the youngest cohort (18 to 24 years) to report knowledge. Interactions between time of recruitment and all predictors were found to be non-significant (p > 0.05 for all interactions).

Identical regressions conducted separately on each of the other three countries found that there was no significant increase in knowledge between the pre and post periods (p > 0.05 for all); however, in Canada, 25 to 39-year-olds (as compared to the reference of 18 to 24-year-old smokers) reported significantly less knowledge (OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.76, p = 0.003). In the UK, male smokers (OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.92), as compared with female smokers, reported higher rates of knowledge. Additionally, in the UK, more highly educated smokers (OR: 2.80, 95% CI: 1.67, 4.42, p < 0.001), as compared with less educated smokers, reported higher rates of knowledge. In the US, lower knowledge was associated with moderate (OR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.43, 0.91, p = 0.014), highest (OR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.33, 0.75, p < 0.001) and unknown income levels (OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.24, 0.94, p = 0.033), as compared with the lowest income group. Additionally, the most highly educated group was more likely to report knowledge of the smoking-blindness link (OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.09, 2.36, p = 0.016) as compared with the least educated American smokers. No other examined factors were found to be associated with knowledge in Canada, UK or the US.

DISCUSSION

Prior to the introduction of the ‘eye’ cigarette pack warning label, Australian smokers reported relatively high knowledge of the causal association between smoking and blindness, with approximately half of smokers reporting that smoking can cause blindness. This was significantly higher than knowledge in Canada, UK or the US and is likely due to the success of national social marketing campaigns that included considerable use of a high-impact television advertisement on the topic.16 The current study finds that the introduction of the Australian ‘eye’ warning label in 2007 is associated with a further increase in the knowledge of adult Australian smokers that smoking causes blindness. In Canada and the US where there were no changes to tobacco product warning labels during the study period, there was no change in knowledge of smoking causing blindness. In the UK, there was a significant increase in knowledge between 2004 and 2005. The reasons for these differences are not clear; however, a national professional education and advocacy program called ‘Smoke gets in your eyes’ was active in the UK between 2004 and 2006 and included efforts to raise the awareness of smoking’s impact on ocular health to ophthalmologists and eye-health organisations, patients, the general public and policy-makers.26 It is important to note that even with these efforts, the vast majority of UK smokers were unaware that smoking causes blindness.

In Australia, knowledge of the causal association about smoking and blindness was not predicted by sex, income, education level or a measure of addictiveness (HSI). The logistic regression model for Australian smokers identified that older Australians, relative to younger, are less likely to report that smoking causes blindness. Analysis revealed that this lack of knowledge was also present prior to the warning labels. Smoking prevention and cessation messaging is important for all ages; however, this finding may help identify a priority for better educating older smokers, especially as the incidence of AMD increases with age.

The year-to-year knowledge of the warning labels also suggests that the annual cycling of the Australian warning labels may impact knowledge. The sampling period October 2008 to July 2009 (Wave 7) of the ITC Four Country Survey best coincides with the time when the Set B labels were in circulation in Australia. In the sampling period between July 2010 and May 2011 (Wave 8), there was a decrease (although not significant) in knowledge, which may be explained by the minimal overlap between survey fieldwork and the ‘eye’ label being in circulation.

Some caution is required in interpreting the overall level of knowledge as the task involved recognition of the problem (that is, agreement to a prompted health risk) rather than unassisted recall. This method is also subject to possible acquiescence bias, but as levels were low in the countries without extensive public education, the difference would appear to be real. Further, respondents were not given any definition of what blindness meant and this may have influenced how participants responded, although this was true across all four countries and cannot be an explanation for the different pre-post pattern of knowledge in Australia compared to the other three countries.

During the study period, non-governmental organisations, including the Macular Degeneration Foundation27 in Australia engaged in a variety of awareness campaigns that may have helped Australians learn about the causal association between smoking and AMD; however, these campaigns did not primarily focus on this one issue.

Despite Australia’s relative success in educating smokers about the association between cigarettes and ocular health, approximately 30 per cent of adult smokers in Australia were either unaware of this important health effect or did not believe the message. The latter possibility is important for ocular health practitioners to consider. When the ‘eye’ warning label was evaluated to inform the Australian government, some participants suggested that the link between smoking and blindness was hard to believe. Some reported having difficulty understanding how smoking affects the eye and how visual loss can result.28 Thus, there is an opportunity for eye-care practitioners to help educate their patients about the health effects and support national prevention and cessation efforts. In 2010, Optometrists Association Australia adopted a position statement on tobacco that states that optometrists have a responsibility to advise their patients of the risks of tobacco smoking and to encourage smokers to stop smoking.29

There have been numerous calls for the optometric community to be engaged in tobacco use cessation and prevention work30,31 and evidence exists that optometrists are open to being more involved.32,33 Integrating the Australian optometric community more meaningfully into the national cessation referral system may be a valuable way to improve national quit rates and address disbelief about smoking causing visual loss. Other countries should take heed and increase their efforts to educate smokers about the link between their smoking and the risk of losing sight.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors acknowledge the support of Pete Driezen in preparing the data set, Mary McNally and Amanda Duncan for support to the ITC Four Country Project.

GRANTS AND FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE

Funding support for the ITC Four Country Survey was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (265903 and 450110), Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, Canadian Institutes for Health Research (57897, 79551, and 115016), U.S. National Cancer Institute (P50 CA111236 and RO1 CA100362), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (045734), Cancer Research UK (C312/A3726, C312/A6465, C312/A11039 and C312/A11943) and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (Senior Investigator Award). Additional support was provided from the Canadian Cancer Society through the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute Junior Investigator Award (Hammond).

REFERENCES

- 1.Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. Technical Report No 2 Tobacco control in Australia: making smoking history Including addendum for October 2008 to June 2009. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/preventativehealth/publishing.nsf/Content/96CAC56D5328E3D0CA2574DD0081E5C0/ $File/tobacco-jul09.pdf.

- 2.Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Health Survey: Summary of Results, 2007–2008. Available at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4364.0Main%20Features42007–2008%20%28Reissue%29?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4364.0&issue=2007–2008%20%28Reissue%29&num=&view=

- 3.Collins D, Lapsley H. The costs of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug abuse to Australian society in 2004/05.P3 2625. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2008. Available from: www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/mono64/$File/mono64.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurwood AS. Relationship between smoking and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Optometry. 2006;77:206. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Smith W, Leeder SR. Smoking and the 5-year incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Blue Mountain Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1357–1363. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RPL. 28,000 cases of age related macular degeneration causing visual loss in people aged 75 years and above in the United Kingdom may be attributable to smoking. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:550–553. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.049726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell P, Chapman S, Smith W. ‘Smoking is a major cause of blindness’. Med J Aust. 1999;171:173–174. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb123591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell P, Taylor HR, Keeffe JE, Vu H, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Pezzullo LM. Vision loss in Australia. Med J Aust. 2005;12:565–568. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Institute for Health and Welfare. Bulletin no. 27. AIHW cat. No. AUS 60. Canberra: AIHW; 2005. Vision problems among older Australians. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=6442453390. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Lee AJ, Chia E-M, Smith W, Cumming R, Mitchell P. Ten year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romer D, Jamieson P. The role of perceived risk in starting and stopping smoking. In: Slovic P, editor. Smoking: Risk, Perception and Policy. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2001. pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pisinger C, Glümer C, Toft U, von Huth Smith L, Aadahl M, Borch-Johnsen K, Jørgensen T. High risk strategy in smoking cessation is feasible on a population-based level. The Inter99 study. Prev Med. 2008;46:579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, Borland R, Cummings KM. Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl III):19–25. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. 1997–2003 National Tobacco Campaign Evaluation Response and Recall Measures among Smokers and Recent Quitters. 2004 Available at: http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/9881124EAEC5A935CA25786000797D14/$File/ntcresp.pdf.

- 15.Carroll T, Rock B. Generating Quitline calls during Australia’s National Tobacco Campaign: effects of television advertisement execution and programme placement. Tob Control. 2003;12(Suppl II):40–44. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy RD, Spafford MM, Parkinson CM, Fong GT. Knowledge about the relationship between smoking and blindness in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia: results from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Project. Optometry. 2011;82:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanahan P, Elliott D. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Graphic Health Warnings on Tobacco Product Packaging 2008. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/F22B9115FD392DA5CA257588007DA955/$File/cover.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australian Commonwealth Government. Health Warnings Campaign 2006. 2009 Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/warnings-lp.

- 19.Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, Hastings G, Hyland A, Giovino GA, Hammond D, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):3–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond D, Boudreau C, Driezen P, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):12–18. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ITC Four Country Survey Team. International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey (ITC FOUR-Country Survey) Wave 1 Technical Report. Available at: http://www.itcproject.org/Library/countries/4country/reports/itcw1techr. [Google Scholar]

- 22.ITC Four Country Technical Report—Waves 2–8. 2011 Sep; available here: http://www.itcproject.org/surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. [Accessed January 22, 2012];Tobacco Health Warnings 2011. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/tobacco-warn.

- 24.Kozlowski L, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, Pope MA, Heatherton T. Predicting smoking cessation with self-reported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND and HSI. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;34:211–216. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorton J, Edwards R, Harrison R, Elton P, Kelly SP. ‘Smoke gets in your eyes’: a research-informed professional education and advocacy programme. J Public Health. 2007;29:142–146. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macular Degeneration Foundation, Annual Reports. Available at: http://www.mdfoundation.com.au/annual_report.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanahan P, Elliott D. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Graphic Health Warnings on Tobacco Product Packaging 2008, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra. 2009 Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/ F22B9115FD392DA5CA257588007DA955/$File/ hw-eval-full-report.pdf.

- 29.Optometrists Association Australia, Position statement on tobacco, July 2010. Available at: www.optometrists.asn.au/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=HERN3gSYx8k%3d&tabid=81& language=en-US] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loo DL, Ng DH, Tang W, Au Eong KG. Raising awareness of blindness as another smoking-related condition: a public health role for optometrists? Clin Exp Optom. 2009;92:42–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2008.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passut J. Primary eye care providers should counsel patients on smoking cessation. Prim Care Optom News. 2008;13:118–119. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon JS, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Severson HH, Akers L, Williams C. Ophthalmologists’ and optometrists’ attitudes and behaviours regarding tobacco cessation intervention. Tob Control. 2002;11:84–85. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.1.84-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy RD, Spafford MM, Schultz ASH, Iley MD, Zawada V. Smoking cessation referrals in optometric practice. A Canadian pilot study. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88:766–771. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318216b203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]