Abstract

Circumsporozoite protein gene sequences of Plasmodium falciparum were collected in 1996–1997 and in 2006–2007 from a single endemic area in Thailand. Repeat units were more similar within the same haplotype than between haplotypes, supporting the hypothesis that repeat arrays evolve by a process of concerted evolution. There was evidence that natural selection has favored amino acid changes in the Th2R and Th3R T-cell epitope regions. One haplotype in these epitopes, designated *5/*1, occurred in approximately 70% of sequences in both collection periods. The most common other haplotypes differed from *5/*1 by at least two amino acid replacements; and divergence in the epitopes was correlated with divergence in the repeats. These patterns are most consistent with balancing selection driven by interactions with the immune system of the vertebrate host, probably involving both T-cell recognition of the Th2R and Th3R epitopes and antibody responses to the repeats.

Keywords: Balancing selection, Circumsporozoite protein, Concerted evolution, Genetic polymorphism, Malaria, Plasmodium falciparum

1. Introduction

The circumsporozoite protein (CSP) of Plasmodium falciparum, the most virulent human malaria parasite, has been studied intensively as a vaccine candidate (Nussenzweig and Nussenzweig, 1989; Sharma and Pathak, 2008). In P. falciparum, the gene encoding CSP (pfcsp) can be divided into three distinct regions: a 5′ non-repeat region (5′NR), a central region encoding >40 repeats of the four amino acid motif NANP (Asn-Ala-Asn-Pro) or a close variant, and a 3′ non-repeat region. Single nucleotide polymorphisms, most of which are nonsynonymous, have been reported in the 3′NR and the 5′NR, while the repeat regions differs among allelic sequences with respect to both the number of repeats and their nucleotide composition (Jongwutiwes et al., 1994). The NANP repeats are known to elicit a strong T-cell independent antibody response on the part of the human host (Ballou et al., 1985; Enea and Arnot, 1998), while in the 3′NR are located peptide epitopes (concentrated in two regions known as Th2R and Th3R) bound by human major histocompatibility complex molecules and presented to T cells (Good et al., 1988).

The forces responsible for maintaining polymorphism at the pfcsp locus have been controversial (Arnot, 1989; Good et al., 1988; Hughes, 1991; Hughes and Hughes, 1995; Jongwutiwes et al., 1994; Kumkhaek et al., 2005; Rich and Ayala, 2000). It has been proposed that the repeats are subject to a form of concerted evolution, whereby repeat arrays expand and contract by internal duplications and deletions, possibly involving a mechanism such as slipped-strand mispairing (Hughes, 1991, 2004; Jongwutiwes et al., 1994; Rich and Ayala, 2000). By contrast, observing that most amino acid variation in non-repeat regions coincides with Th2R and Th3R, Good et al. (1988) proposed that this polymorphism is maintained by natural selection favoring immune evasion. This hypothesis was supported by the observation that the number of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN) is greatly elevated in Th2R and Th3R (Hughes, 1991; Hughes and Hughes, 1995; Jongwutiwes et al., 1994). On the other hand, Kumkhaek et al. (2005) suggested that natural selection on these regions may be exerted not by interactions with the vertebrate immune system but by interactions with the mosquito host.

In order to achieve a better understanding of the evolutionary dynamics of the CSP, it is important to have a clear understanding of the patterns of polymorphism at this locus in natural populations. To date, the most extensive population survey of pfcsp sequences involved a sample of 136 complete sequences from Vanuatu (Tanabe et al., 2004). However, this appears to be an extremely low-diversity population, evidently as a result of a founder effect in colonization of the remote Pacific islands of Vanuatu (Tanabe et al., 2004). Thus, it is unclear whether local populations elsewhere in the world will show patterns similar to that seen in Vanuatu.

Here we analyze complete pfcsp sequences from 223 isolates from a malaria endemic area, Tak Province in Thailand. We examine patterns of polymorphism in both the repeat and non-repeat regions. In the case of the repeat regions, sequence alignment is highly uncertain (Jongwutiwes et al., 1994). Therefore, we apply an alignment-independent measure of sequence similarity (Putaporntip et al., 2008) in order to test for patterns of coevolution between repeat and non-repeat regions. The sequences analyzed were collected during two different time periods, 1996–1997 and 2006–2007. In the decade between these two periods, the number of reported cases of malaria in Thailand decreased more than 50% (Putaporntip et al., 2008). A previous analysis of the pfmsp-2 gene, encoding merozoite surface protein-2 of P. falciparum, showed significant changes in allele frequency between the two samples, which may reflect increased selection intensity due to reduction in the number of available hosts (Putaporntip et al., 2008). Here we tested for evidence of parallel changes in allelic frequency in the case of pfcsp.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. P. falciparum samples

We collected P. falciparum-infected blood samples from 223 symptomatic malaria patients in Tak Province, northern Thailand during 1996–1997 (n = 116) and 2006–2007 (n = 107). DNA of these malaria blood samples was extracted by either using proteinase K digestion followed by phenol/chloroform extraction or using the QIAGEN DNA minikit (Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's protocol. DNA of these samples was previously determined to contain single genotypes of the merozoite surface protein-1 and -2 loci. After the purification procedure, these DNA samples were stored at −30 °C until use. The ethical aspects of this study have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University.

2.2. Amplification of the pfcsp gene

The complete pfcsp gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers whose sequences were derived from the 5′ untranslated region, FCSF0: 5′-CGTGTAAAAATAAGTAGAAACCACG-3′, and the 3′ untranslated region, FCSR0: 5′-GAACACATCTTAGTTTGAGTTGTACA-3′, of the IMTM22 sequence (GenBank accession number K02194). Thermal cycling profiles contained a preamplification denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s; annealing at 50 °C, 30 s; extension at 72 °C, 2 min, and post-amplification extension at 72 °C, 5 min. DNA amplification was performed by using a GeneAmp 9700 PCR thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). We used ExTaq DNA polymerase to minimize the error introduced in the sequences during PCR amplification because it possesses efficient 5′ → 3′ exonuclease activity to increase fidelity and no strand displacement (Takara, Japan). The size of PCR product was examined by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and visualized under a UV transilluminator (Mupid Scope WD, Japan).

2.3. DNA sequencing

DNA sequences were determined directly and from both directions for each template using the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit on an ABI3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA). Overlapping sequences were obtained by using sequencing primers. When singleton substitution was detected, sequence was re-determined using PCR products from two independent amplifications using the same DNA template. DNA sequences were submitted to the Genbank database under the accession numbers FJ232142–FJ232364.

2.4. Statistical methods

In sequence analyses, we compared the sequences from Tak Province with a sample of 90 complete pfcsp sequences from different populations around the world. (For Genbank accession numbers, see Supplemental Figure S1). In the following, we refer to these two samples as the Tak and World samples, respectively. Sequences of 5′ and 3′ non-repeat regions (5′NR and 3′NR) were aligned separately using the CLUSTAL X program (Thompson et al., 1997; Supplemental Figure S1). Sequences of the NANP repeat regions were not aligned. Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed on the basis of the alignment of non-repeat regions by the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). We used the number of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions per non-synonymous site (dN) in phylogenetic reconstruction because nearly all nucleotide differences among alleles in the non-repeat regions of pfcsp were nonsynonymous (see Section 3). The reliability of branching patterns in phylogenetic trees was assessed by bootstrapping (Felsenstein, 1985); 1000 bootstrap samples were used. Prior to phylogenetic analyses, the GENECONV procedure implemented in the RDP3 program (Martin et al., 2005) was used to test for inter-allelic recombination events in the non-repeat regions; none were detected.

We used Nei and Gojobori's (1986) method to estimate dN and the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS). In previous analyses, the methods of Li (1993) and Yang and Nielsen (2000) yielded essentially identical results, as expected because the number of substitutions per site was low in this case (Nei and Kumar, 2000). However, the latter methods were not strictly applicable in the present case because the sequences analyzed were short; the latter methods estimate certain parameters (such as nucleotide composition) from the data, resulting in substantial stochastic error in the case of short sequences.

We computed the mean of all pairwise dS values, designated the synonymous nucleotide diversity (πS); and the mean of all pairwise dN values, designated the nonsynonymous nucleotide diversity (πN). Th2R (17 residues) and Th3R (12 residues), both located in the 3′NR, were defined as in Alloueche et al. (2000). Standard errors of πS and πN were estimated by the bootstrap method (Tamura et al., 2007).

For an alignment-independent measure of the similarity between two repeat arrays, we computed a coefficient of identity (CI; Putaporntip et al., 2008). Let pij and pkj represent the proportion of the jth repeat unit in array i and array k, respectively. Then we define the coefficient of identity as follows:

| (1) |

CI represents the probability that a repeat drawn at random from array i will be identical to a repeat drawn at random from array k. Similarly, the probability that two repeats drawn at random from the same array (array i) will be identical is computed as follows:

| (2) |

We computed CI separately at the nucleotide level and at the amino acid level.

In order to test hypotheses regarding pairwise comparisons of repeat arrays among individual sequences, we used randomization tests. These involved creating 1000 pseudo-data sets by sampling (from replacement) in the original data. A difference in mean between two groups of comparisons was considered significant at the α level if less than 100α% of the pseudo-data sets showed a difference greater than the observed difference.

3. Results

3.1. Non-repeat regions

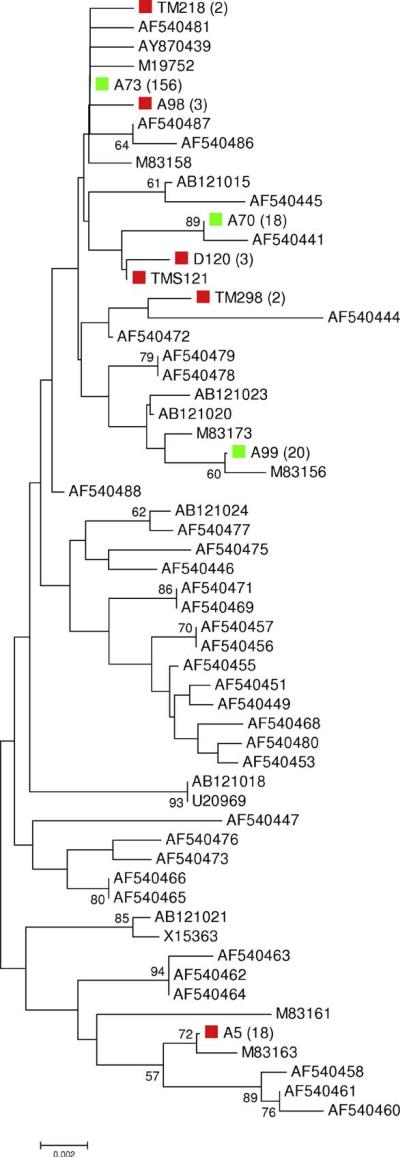

In 223 sequences of pfcsp from Tak Province, Thailand, we found nine unique haplotypes in the non-repeat regions. The 90 sequences in the World sample represented 54 distinct haplotypes in the non-repeat regions, three of which were also found in the Tak sample (Fig. 1). The phylogenetic tree was based on 224 aligned codons, just 30 of which showed any amino acid difference. Because of the limited number of sites, few branches in the tree received very strong bootstrap support (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the sequences from the Tak sample were scattered throughout the tree (Fig. 1). In the Tak sample, the most common haplotype in the non-repeat region (156 sequences) was identical to that of previously reported culture-adapted strains from Thailand (T9/102) and Indochina (Dd2), as well as field samples from Vanuatu.

Fig. 1.

Neighbor-joining tree of unique pfcsp non-repeat region sequences from Tak and World samples, based on dN in 224 aligned codons. Numbers on the branches are percentages of 1000 bootstrap samples supporting the branch; only values ≥50% are shown. Sequences from the Tak sample that were also found in the World sample are marked in green. Sequences unique to the Tak sample are marked in red. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of sequences from the Tak sample showing an identical haplotye in the non-repeat regions.

In the Tak sample, there were no synonymous polymorphisms in the non-repeat regions (Table 1). In the Th2R and Th3R epitope regions, πN was significantly greater than πS in both the Tak sample and the World sample; but there was not a significant difference between πS and πN in the remainder of the non-repeat regions (Table 1). In the Tak sample, mean πN in Th2R and Th3R epitope regions was over 42 times as great as that in the remainder of the non-epitope regions (Table 1). On the other hand, πN in the World sample was significantly (P < 0.05) greater than that in the Tak sample both in the Th2R and Th3R epitope regions and in the remainder of the non-repeat regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Synonymous (πS) and nonsynonymous (πN) nucleotide diversity in Tak and World samples of pfcsp alleles.

| Th2R and Th3R epitopes |

Remainder non-repeat |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| πS (±S.E.) | πN (±S.E.) | πS (±S.E.) | πN (±S.E.) | |

| Tak (N = 223) | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 | 0.0255 ± 0.0094a | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 | 0.0006 ± 0.0006 |

| World (N = 90) | 0.0033 ± 0.0024 | 0.0684 ± 0.0182b,c | 0.0036 ± 0.0028 | 0.0033 ± 0.0014c |

Tests of the hypothesis that πS = πN:

P < 0.01

P < 0.001 (Z-test).

Tests of the hypothesis that πS or πN in the World sample equals the corresponding value in Tak:

P < 0.05 (Z-tests).

We also conducted similar analyses separately for the sequences collected in 1996–1997 and for those collected in 2006–2007; the values of πS and πN were essentially the same for the two time periods (data not shown).

3.2. Four-codon repeats

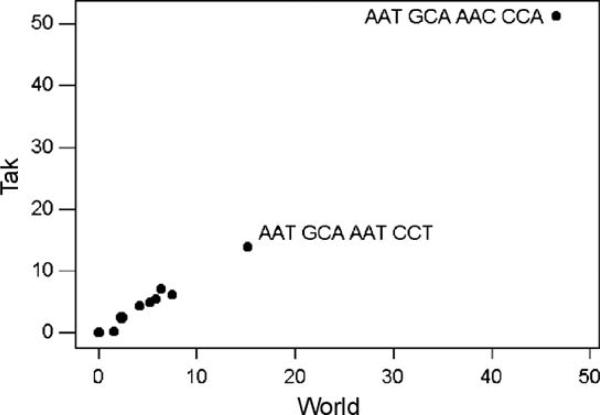

In the repeat regions, the 223 sequences in our Tak sample included a total of 10317 individual four-codon repeats, of which 9385 (91.0%) encoded NANP; 707 (6.9%) encoded NVDP; and 223 (2.2%) encoded NPDP. Of the 64 possible ways of encoding NANP, only 10 were represented in the Tak sample. Moreover, only two ways of encoding NANP accounted for 65.2% of all repeat units: AAT GCA AAC CCA (51.3%) and AAT GCA AAT CCT (13.8%; Fig. 2). The proportions of individual repeat types were highly correlated between the Tak and World samples (r = 0.998; P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The World sample included 12 different repeat types not found in the Tak sample, but these were all rare types. Interestingly, the Tak sample included a repeat type (AAT GCG AAC CCA) not found in the World sample. This repeat type occurred in three separate sequences, in each case in the same haplotype with the most commonly observed haplotype in the non-repeat regions. In sequences from Tak province, the frequencies of repeats were highly correlated between the two collection periods (r = 1.000; P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Plot of the percent occurrence in the Tak sample of nucleotide sequences in the four-codon repeat arrays in the Tak sample vs. the World sample. The sequences of the two most common repeat unit types are shown. The frequency distributions were highly correlated (r = 0.998; P < 0.001).

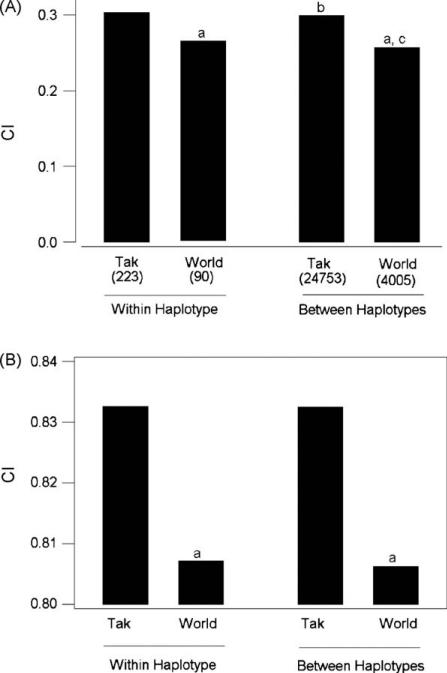

We analyzed the evolution of repeat arrays within and between haplotypes by computing the coefficient of identity (CI) at the nucleotide level. Both within and between haplotypes, mean CI values for the Tak sample were significantly greater than those for the World sample (P < 0.001 in each case; randomization test; Fig. 3A). Thus, in the repeat regions as in the non-repeat regions, the nucleotide sequence diversity was lower in the Tak sample than in the World sample. We used comparison of CI within and between haplotypes to test the hypothesis of concerted evolution of repeat arrays. As predicted under concerted evolution, mean CI within haplotypes was greater than mean CI between haplotypes (randomization test Fig. 3A). In the Tak sample, mean CI within haplotypes (0.303) was significantly greater than that between haplotypes (0.300) at the 0.2% level (Fig. 3A). In the World sample, mean CI within haplotypes (0.264) was significantly greater than that between haplotypes (0.257) at the 0.1% level (randomization test; Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Mean CI based on (A) nucleotide sequences and (B) amino acid sequences in the four-codon repeats of pfcsp. Mean CI was computed separately for comparisons within haplotypes and between haplotypes and for the Tak and World samples. Randomization tests of the hypothesis that mean CI for the Tak sample equals that for the world sample: aP < 0.001. Randomization tests of the hypothesis that mean CI between haplotypes equals that within haplotypes: bP < 0.002; cP < 0.001.

When CI was computed at the amino acid sequence level, mean CI values were much higher than those at the nucleotide sequence level, as expected given the small number of amino acid sequence motifs seen in the repeats (Fig. 3B). Nonetheless, mean CI at the amino acid level was significantly higher in the Tak sample than in the World sample, in both comparisons within haplotype and comparisons between haplotypes (Fig. 3B). Thus, at the amino acid level as well as the nucleotide level, the repeats were less diverse in the Tak sample than in the World sample.

3.3. Th2R and Th3R haplotypes

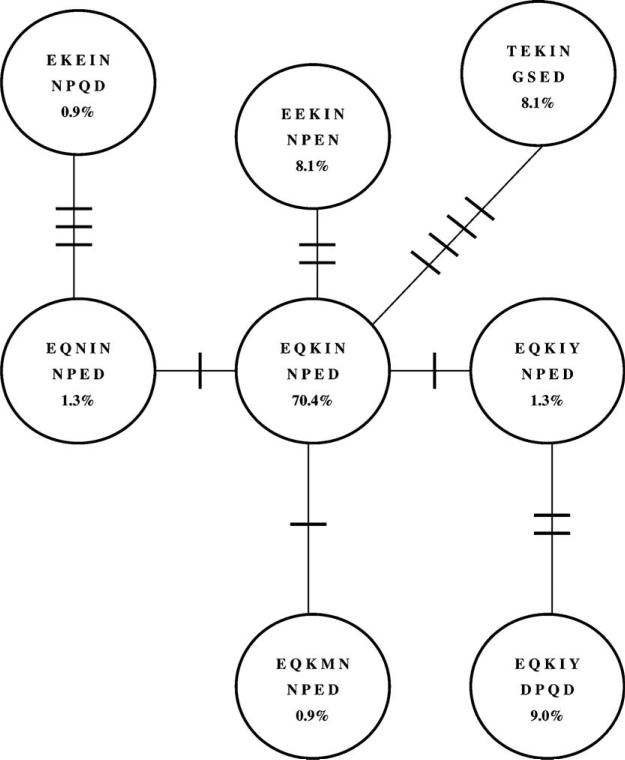

Kumkhaek et al. (2005) found a high prevalence in three regions on the Thailand-Myanmar border of a haplotype in the Th2R and Th3R epitopes which they designated “*5/*1.” In our Tak sample, amino acid sequences in these epitopes belonged to just eight haplotypes; these are illustrated by the sequences at the variable amino acid sites in Fig. 4. The most common haplotype, with a frequency of 70.4% (Fig. 4), was the same haplotype designated *5/*1 by Kumkhaek et al. (2005); this haplotype is designated EQKIN NPED in Fig. 4 on the basis of the residues found at the nine variable amino acid positions in Th2R and Th3R. Three of the seven other haplotypes differed from *5/*1 at just one amino acid site (Fig. 4). However, the three most common haplotypes besides *5/*1 (with frequencies of 8.1–9.0%) all differed from *5/*1 at two or more amino acid sites (Fig. 4). The haplotype most divergent from *5/*1 showed four amino acid differences (TEKIN GSED), and it had a frequency of 8.1% in the Tak sample (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Network illustrating the relationships among the haplotypes (circles) of amino acid sequences in the Th2R and Th3R epitopes found in the Tak sample. Each haplotype is indicated by the amino acid sequence at the nine variable amino acid residues in these epitopes, and the frequency (%) of each haploype in the Tak sample is shown. Cross-hatchings on the lines connecting haplotypes indicate the number of amino acid replacements between them. The most abundant haplotype (EQKIN NPED) is equivalent to that designated *5/*1 by Kumkhaek et al. (2005).

When we compared the frequencies of haplotypes in Th2R and Th3R between the two collection periods, the frequency of *5/*1 remained remarkably constant: 70.7% in 1996–1997 and 70.1% in 2006–2007. The three most common haplotypes other than *5/*1 did show frequency differences between the two collection periods. TEKIN GSED had a frequency of 12.9% in 1996–1997 but of only 2.8% in 2006–2007; and in this case the difference in proportions was significant (P = 0.006; Fisher's exact test). Conversely, EQKIY DPQD had a frequency of 6.0% in 1996–1997 but of 12.1% in 2006–2007. Similarly, EEKIN NPEN had a frequency of 6.0% in 1996–1997 but of 10.3% in 2006–2007. However, the difference in proportions between collection periods was not significant in either of the latter two cases (Fisher's exact test; P > 0.10 in each case). Moreover, the combined frequency of the three most common haplotypes other than *5/*1 scarcely changed between the two collection periods, being 25.0% in 1996–1997 and 25.2% in 2006–2007.

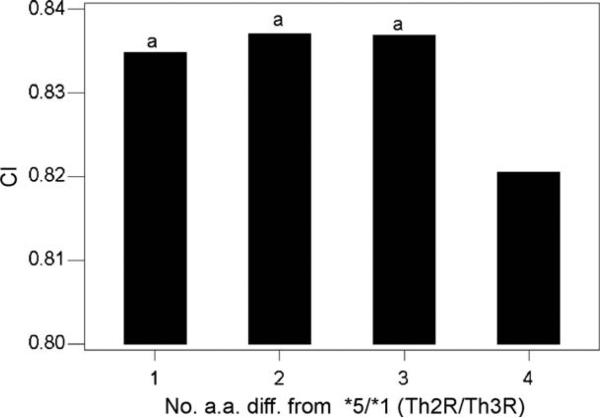

We computed mean CI based on amino acid sequences in the repeat arrays between sequences belonging to the *5/*1 haplotype and sequences of other haplotypes, categorizing the latter by the number of amino acid differences from *5/*1 in Th2R and Th3R (Fig. 5). The mean CI value between repeats from the *5/*1 haplotype and those from sequences with 4 amino acid differences from *5/*1 were significantly lower than those with 1, 2, or 3 differences (P < 0.001in each case; randomization test; Fig. 5). Thus, sequences that differed substantially from the *5/*1 haplotype in Th2R and Th3R also differed significantly in the amino acid composition of the repeats.

Fig. 5.

Mean CI based on amino acid sequences in the repeat arrays, computed between sequences belonging to the *5/*1 haplotype and sequences of other haplotypes, differing from *5/*1 by 1–4 amino acid differences in Th2R and Th3R. Randomization tests of the hypothesis that mean CI for the Tak sample equals that for sequences with 4 differences from *5/*1: aP < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Understanding the sequence variation at pfscsp within individual populations is important because the development of population-specific vaccines will be facilitated if within-population variation at this locus is generally low (Tanabe et al., 2004). Analysis of 223 sequences of the circumsporozoite protein gene (pfcsp) of Plasmodium falciparum from a single endemic area in Thailand, Tak province, revealed substantially greater genetic diversity than did a previous study in Vanuatu (Tanabe et al., 2004) but lower diversity in both repeat and non-repeat regions than did a sample of published sequences from throughout the world. Thus, the Tak province sequences appeared to represent a sub-sample of world genetic diversity at this locus.

Several authors have suggested that the repeat arrays of pfcsp and certain other Plasmodium surface proteins have evolved by a process of concerted evolution, whereby repeats of the same type spread within a given haplotype through mechanisms such as slipped-strand mispairing (Hughes, 1991, 2004; Jongwutiwes et al., 1994; Rich and Ayala, 2000). Here we report the first statistical test of this hypothesis in the case of pfcsp, using a measure (CI) equivalent to the probability of identity of two repeat units chosen at random. Mean CI at the nucleotide level was significantly higher when computed within haplotypes than when computed between haplotypes, supporting the hypothesis of concerted evolution.

As seen in previous analysis (Hughes, 1991; Hughes and Hughes, 1995; Jongwutiwes et al., 1994), the nonsynonymous nucleotide diversity (πN) was significantly elevated in the Th2R and Th3R epitope regions. In fact πN in the epitope regions was over 42 times as great as that in the remainder of the non-repeat regions of the gene. For purposes of comparison, πN in the peptide-binding region of class I MHC loci of humans is only about 5–6 times as high as that in the remainder of the gene (Hughes and Yeager, 1998). These results provide strong evidence that polymorphism in the non-repeat regions is selectively maintained, and that this selection is focused on the Th2R and Th3R epitope regions.

We found no statistical evidence of recombination in the non-repeat regions of pfcsp, in marked contrast to certain other antigen loci of P. falciparum, most notably pfmsp1 (Hughes, 1992). However, the non-repeat regions are relatively short in comparison to the repeat regions, which may decrease the likelihood of recombination events. In addition, the short lengths of the non-repeat regions may limit the ability of statistical methods to detect recombination events. Moreover, if natural selection maintains a balanced polymorphism involving certain distinct haplotypes in the Th2R and Th3R regions (see below), recombination among these haplotypes may be disfavored.

Kumkhaek et al. (2005) proposed that selection on pfcsp may be mediated by interactions with the insect host rather than by vertebrate immune recognition, but it is difficult to understand why such selection would be focused on regions containing epitopes for host MHC class I and class II recognition. Those authors also argued that the high frequency (about 70%) of a single haplotype in the Th2R and Th3R epitopes, which they designated *5/*1, is evidence against balancing selection at this locus (Kumkhaek et al., 2005). Kumkhaek et al. (2005) referred to “fixation” of the *5/*1 haplotype; yet in population genetics “fixation” refers to a frequency of 100%.

The frequency distribution of alleles under balancing selection will depend on the kind of selection (frequency-dependent or overdominant) and the selection coefficients, as well as historical factors such as genetic drift and founder effects. A 70% frequency of one allele is thus perfectly compatible with balancing selection. For example, in West African human populations where the sickle-cell polymorphism is maintained by overdominant selection (heterozygote advantage), the normal allele at the beta-globin locus still has a frequency of about 84% (Cavalli-Sforza and Bodmer, 1971). Under a simple model with two alleles, if one homozygote is less fit than the other homozygote, the frequency of the former allele is expected to be less than that of the latter (Cavalli-Sforza and Bodmer, 1971; Takahata and Nei, 1990). Overdominant selection where the homozygote classes differ in fitness is known as asymmetric overdominance, and sickle-cell anemia in humans provides the best-known example (Cavalli-Sforza and Bodmer, 1971).

In our sample from Tak province, we found the *5/*1 haplotype in 70.4% of sequences, closely matching the results of Kumkhaek et al. (2005). Consistent with asymmetric overdominance, the frequency of the *5/*1 haplotype remained remarkably constant in samples separated by 10 years, in contrast to the changes in allelic frequencies in the variable region of the pfmsp-2 gene over the same period in the same population (Putaporntip et al., 2008). Moreover, the combined frequency of the three most common haplotypes in Th2R and Th3R besides the *5/*1 haplotype (all differing from *5/*1 at two or more amino acid sites) likewise remained remarkably constant in the two collection periods. This distribution could be easily explained if the highest fitness to the parasite were obtained through heterozygous infections including both the *5/*1 haplotype and another haplotype with a substantial degree of amino acid difference from *5/*1. The relative rarity of haplotypes other than *5/*1 is expected if homozygous infections with haplotypes other than *5/*1 are less fit than homozygous infection with *5/*1 alone.

The unchanging frequency of the *5/*1 haplotype is suggestive of selection driven by recognition by the MHC genes of the human host, since the population frequency of MHC alleles is expected to change little over a period of just 10 years. By contrast, the significant change in variable-region allele frequency in pfmsp-2 observed over the same period in the same population is suggestive of selection driven by host antibodies, which change in response to exposure (Putaporntip et al., 2008). Altered peptide–ligand (APL) antagonism, which occurs when the two different but similar CTL epitopes interact in such a way as to prevent the induction of a CTL response (Gilbert et al., 1998; Plebanski et al., 1999), might be one factor contributing to MHC-driven over-dominant selection (Hughes, 1999). Evidence of APL antagonism involving CSP of P. falciparum involved two variant forms of a peptide epitope (KPKDELDY and KSKDELDY) that forms a part of Th3R and is bound by certain human class I MHC allelic products (Gilbert et al., 1998). The haplotype with four amino acid differences from *5/*1 in Th2R and Th3R was the only one in the Tak sample to show the KSKDELDY form of this epitope. By contrast, the *5/*1 haplotype has KPKDELDY.

Some authors have questioned the applicability of over-dominant selection to malaria parasites, since the parasite in the vertebrate host is haploid (Escalante et al., 2004). However, overdominant selection can act at the stage of the diploid zygote if it is advantageous for the zygote to produce sporozoites bearing different alleles at a given locus, thereby increasing the probability of a heterozygous infection of the vertebrate host. Alternatively it is possible that selection on the Th2R and Th3R epitopes is frequency-dependent, rather than overdominant. For example, it is possible that the *5/*1 haplotype has some advantage in initial infection, but that other haplotypes can more easily infect a host already infected with *5/*1. However, formal modeling will be required to demonstrate that this kind of frequency-dependent selection can produce a stable polymorphism, as observed in our study population. On the other hand, it is well known that overdominant selection will yield a stable equilibrium, at least in a large population.

Whatever the kind of balancing selection involved, our results suggested that factors besides APL antagonism at a single epitope are involved in selection on pfcsp. First, the differences among common Th2R and Th3R haplotypes in the Tak population involved residues not involved in this epitope. Furthermore, the Th2R and Th3R haplotype most divergent from *5/*1 also showed a significant reduction of similarity in the amino acid sequences of the repeat regions, as measured by CI. This implies that, in understanding selective pressures on pfcsp, neither the T-cell epitope regions nor the repeat regions can be considered in isolation. Rather, selection at this locus may be driven both by T-cell recognition of epitopes in the non-repeat regions, including both CTL and T-helper cells, and antibody recognition of the repeats.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all patients who donated their blood samples for this study and to Thongchai Hongsrimuang, Sunee Seethamchai and the staff of the Bureau of Vector Borne Disease, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, for assistance in field work. C.P. was supported by The Thailand Research Fund (RMU5080002). This research was supported by grant from the National Research Council of Thailand and the Thai Government Research Budget to C.P and S.J. and grant GM43940 from the National Institutes of Health to A.L.H.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2009.02.006.

References

- Alloueche A, Silveira H, Conway DJ, Bojang K, Doherty T, Cohen J, Pinder M, Greenwood BM. High-throughput sequence typing of T-cell epitope polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000;106:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnot DE. Malaria and the major histocompatibility complex. Parasitol. Today. 1989;5:138–142. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(89)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou WR, Rothbard J, Wirtz RA, Gore RW, Schneider I, Hollingdale MR, Beaudoin RL, Malloy WL, Miller LH, Hockmeyer WT. Immunogeni-city of synthetic peptides from circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1985;228:996–999. doi: 10.1126/science.2988126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Bodmer WF. The Genetics of Human Populations. W.H. Freeman; San Francisco: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Enea V, Arnot D. The circumsporozite gene in Plasmodia. In: Turner MJ, Arnot E, editors. Molecular Genetics of Parasitic Protozoa. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1998. pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante AA, Cornejo OE, Rojas A, Udhayakumar V, Lal AA. Assessing the effect of natural selection in malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SC, Plebanski M, Guptra S, Morris J, Cox M, Aidoo M, Kwiatkowski D, Greenwood BM, Whittle HC, Hill AV. Association of malaria parasite population structure, HLA, and immunological antagonism. Science. 1998;279:1173–1177. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good MF, Pombo D, Quaky IA, Riley EM, Houghten RA, Menon A, Allings DW, Berzofsky JA, Miller LH. Human T-cell recognition of the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum: immunodominant T-cell domains map to the polymorphic regions of the molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:1199–1203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. Circumsporozoite protein genes of malaria parasites (Plasmodium spp.): evidence for positive selection on immunogenic regions. Genetics. 1991;127:345–353. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. Positive selection and interallelic recombination at the merozoite surface antigen-1 (MSA-1) locus of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992;9:381–393. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. Adaptive Evolution of Genes and Genomes. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. The evolution of amino acid repeat arrays in Plasmodium and other organisms. J. Mol. Evol. 2004;59:528–535. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2645-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Yeager M. Natural selection at major histocompatibility complex loci of vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1998;32:415–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MK, Hughes AL. Natural selection on Plasmodium surface proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1995;71:99–113. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongwutiwes S, Tanabe K, Hughes MK, Kanbara H, Hughes AL. Allelic variation in the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum from Thai field isolates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994;51:659–668. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumkhaek C, Phra-ek K, Rénia L, Singhasivanon P, Looareesuwan S, Hirunpetcharat C, White NJ, Brockman A, Grüner AC, Lebrun N, Alloueche A, Nosten F, Khusmith S, Snounou G. Are extensive T cell epitope polymorphisms in the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite antigen, a leading sporozoite vaccine candidate, selected by immune pressure? J. Immunol. 2005;175:3935–3939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W-H. Unbiased estimates of the rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution. J. Mol. Evol. 1993;36:96–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02407308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Williamson C, Posada D. RDP2: recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:260–262. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1986;3:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig RS. Rationale for the development of an engineered sporozoite malaria vaccine. Adv. Immunol. 1989;45:283–334. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60695-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plebanski M, Lee EA, Hannan CM, Flanagan KL, Gilbert SC, Gravenor MB, Hill AV. Altered peptide ligands narrow the repertoire of cellular immune responses by interfering with T-cell priming. Nat. Med. 1999;5:565–571. doi: 10.1038/8444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putaporntip C, Jongwutiwes S, Hughes AL. Differential selective pressures on the merozoite surface protein 2 locus of Plasmodium falciparum in a low endemic area. Gene. 2008;427:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich SM, Ayala F. Population structure and recent evolution of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:6994–7001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.6994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Pathak S. Malaria vaccine: a current perspective. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2008;45:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata N, Nei M. Allelic genealogy under overdominant and frequency dependent selection and polymorphism of major histocompatibility complex loci. Genetics. 1990;124:967–978. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.4.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K, Sakihama N, Kaneko A. Stable SNPs in malaria antigen genes in isolated populations. Science. 2004;303:493. doi: 10.1126/science.1092077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Diggins DG. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:32–43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.