Abstract

Background

Cirrhosis-related abnormal liver function is associated with predisposition to HCC, features in several HCC classification systems and is an HCC prognostic factor.

Aims

To examine the phenotypic tumor differences in HCC patients with normal or abnormal plasma bilirubin levels.

Methods

A 2,416 patient HCC cohort was studied and dichotomized into normal and abnormal plasma bilirubin groups. Their HCC characteristics were compared for tumor aggressiveness features, namely blood AFP levels, tumor size, presence of PVT and tumor multifocality.

Results

In the total cohort, elevated bilirubin levels were associated with higher AFP levels, increased PVT and multifocality and lower survival, despite similar tumor sizes. When different tumor size terciles were compared, similar results were found, even for small tumor size patients. A multiple logistic regression model for PVT or tumor multifocality showed increased OddsRatios for elevated levels of GGTP, bilirubin and AFP and for larger tumor sizes.

Conclusions

HCC patients with abnormal bilirubin levels had worse prognosis than patients with normal bilirubin. They also had increased incidence of PVT and tumor multifocality and higher AFP levels, in patients with both small and larger tumors. The results show an association between bilirubin levels and indices of HCC aggressiveness.

Keywords: HCC, bilirubin, AFP, PVT, multifocality

Introduction

Two general groups of factors have been shown to significantly influence prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. They are tumor aggressiveness factors, such as tumor size and number, presence of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and elevated plasma AFP levels on the one hand; and liver factors, such as plasma levels of bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP), alkaline phosphatase (ALKP) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), on the other hand. Thus, tumor factors and liver microenvironmental factors are thought to independently contribute to survival. These 2 groups of influences are recognized in many HCC classification systems, such as those of Okuda, CLIP, BCLC and JIS (1–5).The CLIP, BCLC and JIS systems use the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score (6) for evaluating liver failure, with emphasis on normal or abnormal bilirubin levels (CLIP, BCLC, JIS, CTP). More recently, inflammatory indices have also been shown to be prognostically significant (7,8). In the present work, we extend our previous analyses of HCC phenotypes (9,10), by examining the possible relationships between normal and abnormal plasma bilirubin levels and indices of HCC aggressiveness. We found that patients with abnormal bilirubin levels had increased markers of tumor aggressiveness.

Methods

Data collection

We retrospectively analyzed prospectively-collected data in the Italian Liver Cancer (ITA.LI.CA) study group database of 2416 HCC patients accrued till 2008 at 11 centers (11) who had full baseline tumor parameter data, including CT scan information on maximum tumor diameter (MTD), number of tumor nodules and presence of PVT and plasma AFP levels; blood counts (hemoglobin, white cells, platelets, prothrombin time); routine blood liver function tests, (total bilirubin, AST,ALKP, GGTP, albumin); demographics (gender, age, alcohol history, presence of hepatitis B or C) and survival information. ITA.LI.CA database management conforms to Italian legislation on privacy and this study conforms to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for this retrospective study on de-identified patients was obtained by the Institutional Review Board of participating centers.

Statistical methodology

Means and standard deviations (M±SD) for continuous variables, and relative frequency for categorical variables, were used as indices of centrality and dispersion of the distribution. Chi-square test for categorical variables, Kruskal-Wallis rank test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann-Whitney test) for continuous variables was used to test associations between groups. Z test for proportions was used for comparison between two categorical variables.

A multiple logistic regression model was used to evaluate association between either PVT or tumor nodule multifocality and selected parameters. When testing the hypothesis of significant association, p-value was <0.05, two tailed for all analyses. All statistical computations used STATA 10.0 Statistical Software, (StataCorp), College Station, TX, USA.

Results

Normal and abnormal plasma bilirubin levels in the total cohort

The total 2416 HCC patient cohort was dichotomized according to median plasma bilirubin levels (1,5 mg/dL), which was close to the upper normal value (1.2 mg/dL) (Table 1). So, patients with bilirubin levels≥1.5 mg/dL were defined as having an “abnormal” value. Patients with abnormal bilirubin levels had lower platelet counts, lower albumin, and higher AST, GGTP and ALKP levels, as expected for presence of elevated bilirubin and liver damage. Maximum tumor diameters (MTD) were not significantly different between the 2 groups. However, the percent of patients with portal vein thrombosis (PVT) or multiple tumor nodules was significantly greater in the abnormal bilirubin group, as were the plasma alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels. Survival in the abnormal bilirubin group that also had more aggressive tumor parameters, was also significantly worse at 1, 2 and 3 years, compared to the normal bilirubin group.

Table 1.

Comparison of HCC patients dichotomized by total bilirubin <1.5 or ≥1.5 mg/dl in the total patient cohort.

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| <1.5 | ≥1.5 | ||

| Parameter* | (n=1443) | (n=973) | p-value# |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 133.7±70.8 | 101.8±58.2 | <0.0001 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.3±2.0 | 12.6±2.1 | <0.0001 |

| GGTP (IU/ml) | 75.8±89.7 | 87.3±116.0 | 0.02 |

| ALKP (IU/ml) | 279.7±1636.3 | 323.1±1355.1 | <0.0001 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.9±0.3 | 3.3±3.7 | <0.0001 |

| PT (%) | 73.4±28.4 | 64.3±22.4 | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.7±0.6 | 3.2±0.6 | <0.0001 |

| AFP (ng/dl) | 1669.2±14552.8 | 2960.5±27737.0 | <0.0001 |

| AST IU/l) | 41.0±51.2 | 53.3±58.3 | <0.0001 |

| MTD (cm) | 4.0±3.2 | 4.3±3.7 | 0.12 |

| PVT (%) | 124 (8.7) | 144 (15.0) | <0.001^ |

| # tumor nodules (>3) (%) | 218 (16.0) | 206 (23.1) | <0.001^ |

| Survival time (%) | |||

| 1yr | 950 (74.0) | 516 (59.3) | <0.001¥ |

| 2yr | 686 (53.5) | 304 (34.9) | <0.001¥ |

| 3yr | 478 (37.3) | 189 (21.7) | <0.001¥ |

All values: Means ± Standard Deviation;

Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test;

Chi-square test;

Test z for proportions.

Abbreviations: MTD, Maximum Tumor Diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombosis; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; GGTP, gamma glutamyl transpeptidae; ALKP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransaminase

Tumor size and bilirubin dichotomization

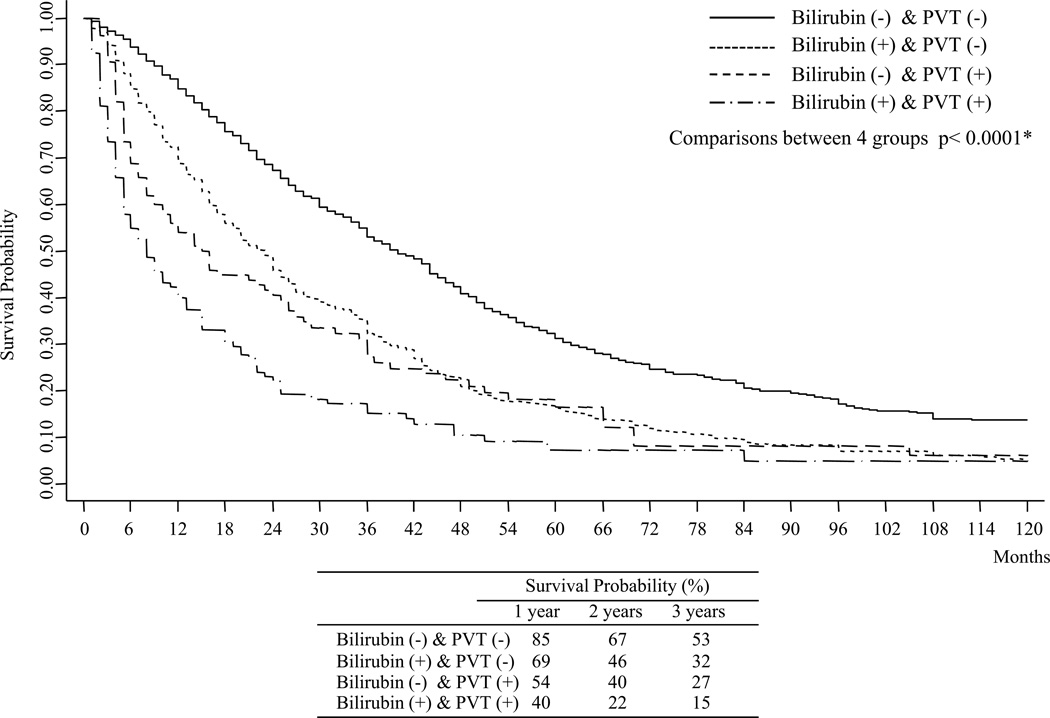

Tumor size is one of several prognostic factors in HCC patients and we previously found that maximum tumor diameter (MTD) terciles can reflect differences in HCC biology (10), with larger size HCCs often being found in patients with better liver function. The total cohort was therefore dichotomized according to bilirubin levels, with the different tumor diameter terciles being examined separately (Table 2). Within each tumor diameter tercile group, there was shorter survival for patients with abnormal bilirubin levels. Again, patients with abnormal bilirubin had worse albumin and AST levels, whereas GGTP levels were significantly higher only in the largest tumor tercile group, and ALKP levels in the intermediate and last tercile groups.. The MTDs were again not different between the normal and abnormal bilirubin groups in each tumor size tercile. However, the percent of patients with PVT or multiple tumors was significantly greater in the abnormal bilirubin group in both the small and large tumor size terciles. Since the incidence of PVT was higher in each size tercile subgroup with abnormal bilirubin, survival was next examined for both parameters, using the Kaplan-Meier method (Fig 1). We found that best survival was in patients with normal bilirubin and without PVT. Worse survival was found for patients with both abnormal bilirubin and presence of PVT. Patients with only abnormal bilirubin or only presence of PVT had intermediate survival, although the adverse prognostic impact of an abnormal bilirubin was lower than that of PVT.

Table 2.

Comparisons between HCC patients dichotomized by total blood bilirubin levels of <1.5 or ≥1.5 mg/dl, in separate tumor size terciles.

| MTD≤2.4cm | 2.5cm≤MTD≤3.9cm | MTD≥4.0cm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | |||||||

| <1.5 | ≥1.5 | <1.5 | ≥1.5 | <1.5 | ≥1.5 | ||||

| Parameter* | (n=439) | (n=271) | p# | (n=445) | (n=300) | p# | (n=559) | (n=402) | p# |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 120.3±61.4 | 91.4±48.9 | <0.0001 | 124.3±61.4 | 94.5±51.1 | <0.0001 | 151.8±80.4 | 114.4±66.4 | <0.0001 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.3±2.0 | 12.8±2.2 | 0.0004 | 13.3±1.9 | 12.6±1.9 | <0.0001 | 13.3±2.1 | 12.5±2.1 | <0.0001 |

| GGTP (IU/ml) | 65.7±92.7 | 66.1±64.5 | 0.95 | 69.3±82.2 | 82.3±149.4 | 0.55 | 88.8±91.5 | 105.1±111.9 | 0.009 |

| ALKP (IU/ml) | 239.8±723.7 | 261.6±496.7 | 0.53 | 233.1±479.5 | 366.0±2206.8 | 0.02 | 349.4±2526.9 | 332.5±812.4 | <0.0001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.9±0.3 | 3.2±3.9 | <0.0001 | 0.9±0.3 | 3.1±3.6 | <0.0001 | 0.9±0.3 | 3.4±3.5 | <0.0001 |

| PT (%) | 68.1±31.3 | 60.3±22.5 | <0.0001 | 75.3±26.9 | 63.6±23.4 | <0.0001 | 76.0±26.5 | 67.3±21.1 | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.7±0.6 | 3.2±0.6 | <0.0001 | 3.7±0.6 | 3.3±0.6 | <0.0001 | 3.7±0.6 | 3.2±0.6 | <0.0001 |

| AFP (ng/dl) | 319.0±2669.0 | 460.0±3247.8 | 0.96 | 546.1±3496.3 | 2639.2±24913.9 | 0.03 | 3604.7±22870.6 | 4837.4±37046.7 | <0.0001 |

| AST IU/l) | 40.4±32.1 | 49.5±42.3 | 0.0009 | 42.2±55.9 | 56.9±78.6 | <0.0001 | 40.4±32.6 | 53.2±49.2 | <0.0001 |

| MTD (cm) | 1.8±0.4 | 1.8±0.4 | 0.62 | 3.0±0.4 | 3.0±0.4 | 0.39 | 6.5±3.8 | 7.0±4.5 | 0.39 |

| PVT (%) | 23 (5.2) | 24 (8.8) | 0.05^ | 26 (5.8) | 31 (10.3) | 0.02^ | 75 (13.4) | 89 (22.1) | 0.001^ |

| # tumor nodules (>3) (%) | 35 (8.2) | 45 (17.4) | <0.001^ | 63 (14.1) | 62 (20.1) | 0.08^ | 121 (24.3) | 109 (31.8) | 0.02^ |

| Survival time (%) | |||||||||

| 1yr | 321 (82.1) | 182 (73.4) | 0.009¥ | 306 (77.3) | 185 (69.0) | 0.02¥ | 323 (65.1) | 149 (42.1) | <0.001¥ |

| 2yr | 252 (64.4) | 119 (48.0) | <0.001¥ | 226 (57.1) | 105 (39.2) | <0.001¥ | 208 (41.9) | 80 (22.6) | <0.001¥ |

| 3yr | 180 (46.0) | 77 (31.0) | <0.001¥ | 160 (40.4) | 63 (23.5) | <0.001¥ | 138 (27.8) | 49 (13.8) | <0.001¥ |

All values: Means ± Standard Deviation;

Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test;

Chi-square test;

Test z for proportions; MTD, Maximum Tumor Diameter.

Other abbreviations, as in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival plots for the total cohort.

Comparisons between: Bilirubin (−) & PVT (−) vs Bilirubin (−) & PVT (+) (p<0.0001*); Bilirubin (−) & PVT (−) vs Bilirubin (+) & PVT (−) (p<0.0001*); Bilirubin (−) & PVT (−) vs Bilirubin (+) & PVT (+) (p<0.0001*); Bilirubin (−) & PVT (+) vs Bilirubin (+) & PVT (−) (p=0.005*). * Wilcoxon (Breslow) test; Bil(−): Total Bilirubin<1.5mg/dl; Bil(+): Total Bilirubin≥1.5mg/dl; PVT(−) : PVT(No); PVT(+): PVT(yes)

Multiple logistic regression model on PVT or tumor multifocality

The analyses in Tables 1 and 2 showed an association of increased PVT or tumor multifocality with elevated plasma bilirubin levels. Since PVT and tumor multifocality (5, 12) are important indices of HCC aggressiveness, we constructed a multiple logistic regression model for each of these 2 parameters of HCC biology, using the median values as cutoffs of five liver function tests and AFP in the total cohort (Table 3). For PVT positivity, the highest Odds Ratios were for large tumor size and multifocality, elevated AFP, bilirubin and GGTP levels. For tumor multifocality, the highest Odds Ratios were for large tumor size and presence of PVT, elevated AFP, bilirubin and GGTP levels, as well as elevated AST levels (in contrast to PVT). Further analysis of several factors together provided no evidence of parameter interaction (Interaction: total bilirubin × number of nodules OR=1.04; [0.51 to 2.09] [95%C.I.], p=0.92. Interaction: total bilirubin × PVT OR= 1.08; [0.53 to 2.23] [95%C.I.], p=0.82).

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression model, corrected for sex and age and alcohol, on PVT (+/−) or Number of Nodules (≤3 or >3) of single variables (A). Final multiple logistic regression model (B).

| PVT(+)$ | Number of Nodules (>3)$ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | se(OR) | p | 95% C.I. | OR* | se(OR) | p | 95% C.I. | |

| (A) Single variables | ||||||||

| GGTP (>100) (IU/ml) | 1.57 | 0.24 | 0.004 | 1.16 to 2.13 | 1.54 | 0.20 | 0.001 | 1.19 to 2.00 |

| ALKP (≥200) (IU/ml) | 1.18 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.88 to 1.60 | 1.03 | 0.13 | 0.81 | 0.81 to 1.31 |

| Total Bilirubin (≥ 1.5) (mg/dl) | 1.79 | 0.25 | <0.001 | 1.36 to 2.35 | 1.57 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 1.25 to 1.98 |

| AFP (>100) (ng/dl) | 2.32 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 1.77 to 3.06 | 2.13 | 0.26 | <0.001 | 1.68 to 2.70 |

| AST (>34) (IU/l) | 1.12 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.85 to 1.47 | 1.43 | 0.17 | 0.002 | 1.14 to 1.80 |

| MTD (cm) | ||||||||

| (≤2.4) [Ref. category] | 1 | -- | -- | -- | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| 2.5–3.9 | 1.15 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.77 to 1.72 | 1.47 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 1.07 to 2.02 |

| ≥4.0 | 2.86 | 0.50 | <0.001 | 2.03 to 4.04 | 3.10 | 0.46 | <0.001 | 2.32 to 4.15 |

| PVT (%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2.34 | 0.37 | <0.001 | 1.71 to 3.19 |

| Number of Nodules (>3) (%) | 2.34 | 0.37 | <0.001 | 1.71 to 3.20 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (B) Final model | ||||||||

| GGTP (>100) (IU/ml) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.37 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 1.03 to 1.82 |

| ALKP (≥200) (IU/ml) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Total Bilirubin (≥ 1.5) (mg/dl) | 1.59 | 0.27 | 0.006 | 1.15 to 2.22 | 1.30 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 1.01 to 1.68 |

| AFP (>100) (ng/dl) | 1.63 | 0.29 | 0.005 | 1.16 to 2.31 | 1.82 | 0.25 | <0.001 | 1.39 to 2.37 |

| AST (>34) (IU/l) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.29 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 1.001 to 1.67 |

| MTD (cm) | ||||||||

| (≤2.4) [Ref. category] | 1 | -- | -- | -- | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| 2.5–3.9 | 0.99 | 0.24 | 0.96 | 0.61 to 1.61 | 1.41 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.98 to 2.04 |

| ≥4.0 | 2.01 | 0.45 | 0.002 | 1.30 to 3.12 | 2.63 | 0.46 | <0.001 | 1.87 to 3.69 |

| PVT (%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.82 | 0.34 | 0.001 | 1.27 to 2.62 |

| Number of Nodules(>3) (%) | 1.83 | 0.33 | 0.001 | 1.27 to 2.62 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Reference category: PVT (−); Number Nodules (1–3);

Odds Ratio MTD, maximum tumor diameter; PVT, portal vein thrombus; all other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Interaction in the final multiple logistic regression: on PVT - total bilirubin ×

Number of Nodules

OR=1.04; (0.51 to 2.09)

(95%C.I.); p=0.92

on Number of Nodules - total bilirubin × PVT OR= 1.08; (0.53 to 2.23) (95%C.I.); p=0.82

Discussion

Many factors have been found to be prognostically important for HCC, but they can generally be grouped into liver-related (bilirubin and other liver function tests) or tumor aggressiveness related (tumor size, presence of PVT, multifocality or elevated AFP levels). The practical significance is that since HCC arises mainly on a background of chronic liver injury (cirrhosis), a patient can die from either liver failure (liver factors) or HCC growth and invasion (tumor factors), or both. The severity of each of these two liver diseases, both cirrhosis and HCC, needs to be taken into account in HCC patient management decisions and prognostication. The presence of hypoalbuminemia and C-reactive protein hasrecently been shown to be prognostically important indices of inflammation in many tumor types, including HCC (7,8). Several classification systems include a cutoff for normal or abnormal plasma bilirubin levels, often a bilirubin >2.0 mg/dl, based on the CTP system (6,2). We examined cutoffs of 1.2 (upper limit of our normal), 1.5 (median value for our total cohort) and 2.0(CTP) mg/dl, but they resulted in the same outcomes (data not shown), and we thus used the median bilirubin value. The principal finding in this study was an association of abnormal plasma bilirubin with elevated levels of 3 indices of clinical HCC aggressive biology, namely plasma AFP levels, PVT and tumor multifocality. Large tumors have previously been noted to occur in patients with preserved liver function (13–15) and this has been thought to be due in part to the likelihood of liver decompensation and death that result when HCCs grow in severely damaged livers. However, we tried to account for this by examining different tumor size terciles (Table 2) and found the association of abnormal bilirubin with aggressive HCC features even in patients with small size tumors, which could not be causing liver failure. Thus, while large HCCs can undoubtedly cause destruction of the extratumoral liver parenchymal, that cannot be considered an important cause of hyperbilirubinemia in patients with small tumors.

Our analysis does not permit us to infer an interaction between liver and tumor factors, only that abnormal bilirubin levels are associated with enhanced tumor aggressiveness, as seen in the bilirubin dichotomization (Tables 1 and 2) and the multiple logistic regression analysis(Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier survival plots showed that presence of either abnormal bilirubin or PVT was associated with worse survival that presence of neither alone, and much worse survival was found when both were present. Microenvironmental factors have recently been recognized as important in the biology of many tumors, including HCC (16–19), and these include liver damage and inflammation factors, as recognized in the Glasgow Prognostic Score (7). However, this is the first report, to our knowledge, of an association of abnormal bilirubin with aggressive HCC features regardless of tumor size. Pertinently, it is worth to note that in patients with small HCCs abnormal bilirubin was dissociated with an elevation of cholestatic enzymes ALKP and GGT (Table 2). This suggests that hyperbilirubinemia cannot be purely ascribed to the “occupying space” effect of tumor mass, but a possible interaction between liver damage and HCC biology and environmental inflammatory status may also be suspected. The associations we found (Table 2) between abnormal bilirubin and high plasma AFP –already reported (20) - and AST levels are suggestive of this type of interaction.

Acknowledgements

Grant support: none

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- GGTP

gamma glutamyl transpeptidase

- ALKP

alkaline phosphatase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- PT

prothromin time

- PVT

portal vein thrombosis

- MTD

maximum tumor diameter

- CT

computerized axial tomography scan

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: none;

No authors have any proprietary or financial interests.

Author statement. This MSS is approved by all authors, who approve the author listing. I act as guarantor.

Author contributions. All co-authors except the first two, collected the clinical data. 1st author analyzed the database and wrote the paper, with corrections by the co-authors. Dr. Guerra did the statistical analyses.

References

- 1.Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Obata H, et al. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Cancer. 1985;56:918–928. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850815)56:4<918::aid-cncr2820560437>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer of the liver Italian programme (CLIP) investigators. A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grieco A, Pompili M, Caminiti G, Miele L, Covino M, Alfei B, Rapaccini GL, Gasbarrini G. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with early-intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing non-surgical therapy: comparison of Okuda, CLIP, and BCLC staging systems in a single Italian centre. Gut. 2005;54:411–418. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.048124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tateishi R, Yoshida H, Shiina S, Imamura H, Hasegawa K, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Koike Y, Fujishima T, Makuuchi M, Omata M. Proposal of a new prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma: an analysis of 403 patients. Gut. 2005;54:419–425. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–664. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinoshita A, Onoda H, Imai N, Iwaku A, Oishi M, Tanaka K, Fushiya N, Koike K, Nishino H, Matsushima M, Saeki C, Tajiri H. The Glasgow Prognostic Score, an inflammation based prognostic score, predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinato DJ, Stebbing J, Ishizuka M, Khan SA, Wasan HS, North BV, Kubota K, Sharma R. A novel and validated prognostic index in hepatocellular carcinoma: the inflammation based index (IBI) J Hepatol. 2012;57:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr BI, Buch SC, Kondragunta V, Pacoska P, Branch RA. Tumor and liver determinants of prognosis in unresectable HCC: a case cohort study. J Gastroenterology Hepatology. 2008;23:1259–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr BI, Guerra V, Pancoska P. Thrombocytopenia in relation to tumor size in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2012;83:339–345. doi: 10.1159/000342431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santi V, Buccione D, Di Micoli A, Fatti G, Frigerio M, Farinati F, et al. The changing scenario of hepatocellular carcinoma over the last two decades in Italy. J. Hepatol. 2012;56:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minagawa M, Makuuchi M. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma accompanied by portal vein tumor thrombus. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7561–7567. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i47.7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuda K, Nakashima T, Kojiro M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma without cirrhosis in Japanese patients. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:140–146. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trevisani F, D’Intino PE, Caraceni P, et al. Etiologic factors and clinical presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Differences between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic Italian patients. Cancer. 1995;75:2220–2232. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950501)75:9<2220::aid-cncr2820750906>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr BI, Guerra V. Features of massive hepatocellular carcinomas. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:101–108. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283644c49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu SD, Ma YS, Fang Y, Liu LL, Fu D, Shen XZ. Role of the micro-environment in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JD, Nakamura I, Roberts LR. The tumor micro-environment in hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and therapeutic targets. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Gea V, Toffanin S, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Role of the micro-environment in the pathogenesis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:512–527. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.002. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr BI, Guerra V. HCC and its microenvironment. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1433–1437. doi: 10.5754/hge121028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pancoska P, Carr BI, Branch RA. Network-based analysis of survival for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Seminars in Oncology. 2010;37:170–181. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]