Abstract

Objective

To evaluate risk factors for unsuccessful instrumental delivery when variability between individual accoucheurs is taken into account.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of attempted instrumental deliveries over a 5-year period (2008–2012 inclusive) in a tertiary U.K. center. To account for inter-accoucheur variability, we matched unsuccessful deliveries (cases) with successful deliveries (controls) by the same operators. Multivariate logistic regression was used to compare successful and unsuccessful instrumental deliveries.

Results

Three thousand seven hundred ninety-eight Instrumental deliveries of vertex-presenting, single, term infants were attempted, of which 246 were unsuccessful (6.5%). Increased birth weight (OR=1.11 p<0.001), second-stage duration (OR=1.01 p<0.001), rotational delivery (OR=1.52 p<0.05) and use of ventouse versus forceps (OR=1.33 p<0.05) were associated with unsuccessful outcome. When interaccoucheur variability was controlled for, instrument selection and decision to rotate were no longer associated with instrumental delivery success. More senior accoucheurs had higher rates of unsuccessful deliveries (12% v. 5%, p<0.05), but undertook more complicated cases. Cesarean delivery in the second stage without prior attempt at instrumental delivery was associated with higher birth weight (OR=1.07 p<0.001), increased maternal age (OR=1.03 p<0.01), and epidural analgesia (OR=1.46 p<0.001).

Conclusion

Results suggest that birth weight and head position are the most important factors in successful instrumental delivery, whereas the influence of instrument selection and rotational delivery appear to be operator-dependent. Risk factors for lack of instrumental delivery success are distinct from risk factors for requiring instrumental delivery, and these should not be conflated in clinical practice.

Introduction

Between 5 and 20% of infants are delivered by instrumental (operative vaginal) delivery in developed countries (1). Overall, approximately 5–10% of attempted instrumental deliveries will fail (2). Unsuccessful attempts are associated with a higher risk of adverse maternal outcomes than proceeding directly to cesarean delivery, including increased rates of general anesthetic and wound infection (3), as well as psychological trauma. Women who have had a previous failed attempt are likely to opt for an elective repeat cesarean delivery rather than another attempted vaginal birth (4). Where instrumental delivery is indicated due to fetal distress, neonatal outcomes also tend to be worse following an unsuccessful attempt (3).

Established risk factors for requiring instrumental delivery include advanced maternal age (5), high body mass index (BMI), epidural analgesia, and high birth weight (6, 7). It is uncertain, however, whether or how these factors influence the outcome of instrumental delivery. The conflation of factors predicting the need for instrumental delivery with factors predicting the likelihood of success may be inappropriate and misleading in intra-partum decision-making. The alternative to attempting instrumental delivery, however, is to directly perform second stage cesarean delivery, which also carries a high burden of morbidity (8). A recent Cochrane review concluded that there is no evidence from randomized trials to guide the accoucheur in the decision to attempt an instrumental delivery versus proceeding directly to cesarean delivery (1). The aim of this study is to identify risk factors for unsuccessful instrumental delivery, and thus aid the accoucheur in difficult decision-making.

Material and Methods

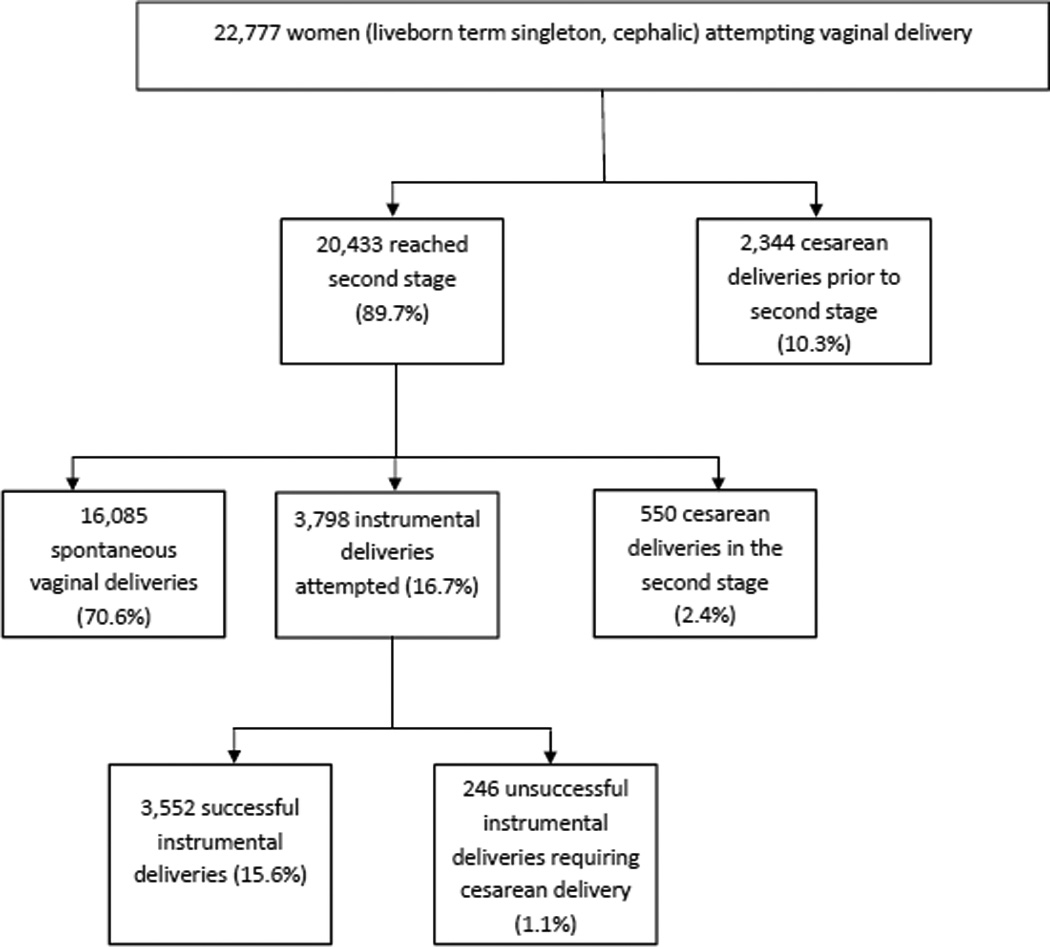

A cohort of 22,777 women with vertex-presenting, single, liveborn infants at term (37 – 42 completed weeks of gestation), aiming for vaginal delivery was identified over a 5-year period in a single tertiary obstetrics center in the United Kingdom. Data regarding each woman’s pregnancy, labor, and delivery were recorded by midwives shortly after the birth, and were subsequently obtained from the hospital’s Protos maternity data-recording system. This database is regularly validated by a rolling program of audits in which the original case-notes are checked against the information recorded in the database. Deliveries were classified according to the final mode of delivery (Figure 1). Unsuccessful instrumental deliveries were defined as those where an instrument was applied to the fetal head, but the eventual mode of delivery was cesarean delivery. The use of sequential instruments, where any instrument was successful in delivering the baby, was considered a successful delivery by the last instrument used. The rate of attempted instrumental delivery did not vary significantly by year during the study period, nor did the rate of unsuccessful instrumental delivery. The indications and procedures for instrumental delivery in our center are as defined in the operative vaginal delivery guidance from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG, UK) (9).

Figure 1.

Outcomes of all deliveries within the study period

Characteristics of the materno-fetal dyad were extracted from the hospital database, including maternal age (at time of delivery), BMI (at first trimester prenatal booking), parity (prior to delivery), ethnicity, and the birth weight of the infant. Birth weight was recorded to the nearest gram. Variables related to the delivery attempt were also noted: whether epidural analgesia was used prior to the delivery attempt, the length of time between diagnosis of second stage and the time of delivery (time fully dilated), and the instrument selected. Gestational age was recorded to the nearest week. Only those cases where birth occurred within the interval 37–42 weeks completed gestation were included. No adjustment was made for infants found to be small or large for gestational age. No record of the station of the presenting part was available within our dataset. However, to our knowledge, no delivery was carried out where the presenting part was above the level of the ischial spines, as recommended by RCOG guidelines (9).

The seniority of accoucheur attempting delivery was also recorded, and classified into four types. Type 1 accoucheurs were doctors within 4 years of leaving medical school; this group conducted only 70 deliveries under supervision during the study period. Type 2 accoucheurs are doctors with 3–5 years of obstetric training. Type 3 accoucheurs are senior trainees with 5–10 years of obstetric training. Type 4 accoucheurs typically have >10 years of clinical obstetric experience. Our study was conducted in a unit where 2 obstetricians are available to perform instrumental deliveries or cesarean deliverys during a 12-hour shift. The first of these obstetricians is typically a type 2 accoucheur, and the second is a doctor with >5 years obstetric training––a type 4 accoucheur during the day, or a type 3 accoucheur overnight. All of the senior obstetricians (Type 3 or 4) were willing to attempt fetal head rotation, where they considered this to be safe. The method of fetal head rotation varied between different accoucheurs, but included any of manual rotation, ventouse (using the Kiwi Omnicup, rotational or posterior metal cup) and Kielland's forceps. The position of the fetal head is not available within our database, but the majority of babies who were not in the occipito-anterior position are most likely to have undergone an attempt at rotation in accordance with standard procedure. A small number may have been delivered in the direct occipito-posterior position, but this would be a highly unusual occurrence, and data are not recorded.

In our statistical analyses, group-wise comparisons were carried out using either Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test for numerical data, and Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical data. Several multivariate regression models were also fit, as described below. Findings were considered statistically significant at an alpha level of 0.05. All data analysis was conducted using the R statistical software package version 2.14.1.

Failed instrumental delivery was modeled using logistic regression with the following covariates: birth weight, maternal age, ethnicity, maternal BMI, seniority of accoucheur, parity, delivery during daylight hours, and use of epidural analgesia. Separate analyses were run for two cohorts: the full cohort, and a case-control subset. The full cohort comprised all successful and unsuccessful instrumental deliveries. The case-control subset comprised all unsuccessful instrumental deliveries (“cases”), together with only those successful deliveries that occurred within the same 12-hour shift as an unsuccessful delivery (“controls”). The goal of analyzing the case-control subset separately is to account for multiple sources of unobservable variation specific to a delivery unit that cannot be readily modeled. This includes the experience and clinical judgment of a particular accoucheur, the workload of the unit during a given shift, the clinician with overall responsibility for the unit, subtle variations in day versus night shifts or weekends, and other intangible environmental factors. The inter-accoucheur variability within the data is also significantly reduced by this strategy, as a maximum of 2 accoucheurs will be available for deliveries within any 12-hour shift. Analysis of the case-control subset is important for testing the robustness of our conclusions, as differences among operators may account for significant variability in the full cohort.

A further consideration is that the more senior accoucheurs are likely to have performed more difficult cases, thereby skewing the apparent success rates. To check the robustness of our findings, we therefore ran separate analyses stratified by accoucheur type, examining the associations between failed instrumental delivery and those predictors that appeared significant in the full cohort model.

Given the influence of birth weight on the likelihood of success of instrumental delivery, we examined whether birth weight is predictable using only those covariates that are observable by the accoucheur prior to attempting instrumental delivery. This was done using ordinary least squares, with predictors chosen via BIC (Bayesian information criterion).

As a final robustness check, we also used CART, or classification and regression trees (10) to build nonlinear predictive models both for failed instrumental delivery and for birth weight. CART allows us to uncover both nonlinear structure and interactions among the predictors, thereby relaxing the more stringent parametric assumptions of linear and logistic regression.

Finally, we sought to identify any systematic differences between women who underwent an attempted instrumental delivery (regardless of the outcome), compared to those who went directly to cesarean delivery in the second stage. We therefore examined the associations between first attempted mode of delivery and the covariates included in the original logistic regression analyses of successful instrumental delivery.

No patient-identifiable data was accessed in the course of this research, which was performed as part of a provision of service study for the obstetrics center. Institutional review board approval was therefore not required.

Results

Three thousand seven hundred ninety-eight instrumental deliveries were attempted, representing 16.7% of all attempted vaginal deliveries. Two hundred forty-six (6.5%) attempts at instrumental delivery were unsuccessful. The overall number of instrumental deliveries performed did not differ between day and night shifts, nor did the rate of unsuccessful instrumental deliveries change between days and nights.

Characteristics of the materno-fetal dyad were compared according to the outcome of attempted instrumental delivery (Table 2). Only gestational age (p<0.01) and birth weight (p<0.001) exhibited statistically significant differences between the two groups. Characteristics of the delivery attempt were also compared according to outcome (Table 2). Several statistically significant differences between the groups emerged: the instrumental selected (p<0.05), need for rotation of the fetal head (p<0.001), seniority of accoucheur (p<0.001), epidural analgesia (p<0.001), and time fully dilated (p<0.001). Sequential instruments were used in 14 cases of unsuccessful instrumental delivery (0.36% of the study population); in 12 of these an attempt at forceps delivery was made following failed ventouse, and in 2 cases the sequence was reversed. As there were a small number of these cases, they have been categorized according to the last instrument used.

Table 2.

All Cases of Successful Instrumental Delivery Compared to All Cases of Unsuccessful Instrumental Delivery, Using Multivariate Analysis With a Binomial Logistic Regression Model

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Rotation (not required) | Ref |

| Rotation (required) | 1.52 (1.02 – 2.36)* |

| Birth weight (per 100g increase) | 1.11 (1.08 – 1.15)† |

| Time fully dilated | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.01)† |

| Parity | 0.91 (0.75 – 1.24) |

| Maternal age | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.04) |

| Day shift | Ref |

| Night shift | 0.93 (0.75 – 1.23) |

| Instrument (forceps) | Ref |

| Instrument (ventouse) | 1.33 (1.01 – 1.77)* |

| Ethnicity - Caucasian | Ref |

| Ethnicity - Black | 1.06 (0.17 – 3.57) |

| Ethnicity – Southeast Asian | 1.45 (0.74 – 2.58) |

| Ethnicity - Chinese | 0.10 (0.00 – 21.38) |

| Ethnicity – other/unknown | 1.30 (0.59 – 2.50) |

| No epidural | Ref |

| Epidural | 1.23 (0.92 – 1.67) |

Model coefficients are expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Associations that meet the threshold for statistical significance (alpha-level = 0.05) are shown in boldface.

p<0.05.

p<0.001

CI, confidence interval.

Table 2 shows the results of the regression analysis for the full cohort. Unsuccessful instrumental delivery is associated with increased birth weight (OR=1.11, p<0.001), longer time fully dilated prior to instrumental delivery (OR=1.01, p<0.001), need for rotation of the fetal head (OR=1.52, p<0.05), and the use of ventouse rather than forceps (OR=1.33, p<0.05).

Table 3 shows the results of the regression analysis for the case-control subset. Increased birth weight (p<0.001) and longer time fully dilated (p<0.001) remain statistically significant, even after accounting for inter-accoucheur variability. The need for rotation and the instrument used are no longer significant at the 0.05 level.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis Using a Binomial Logistic Regression Model of Matched Cases and Controls

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Rotation (not required) | Ref |

| Rotation (required) | 2.24(0.97 – 5.26) |

| Birth weight (per 100g increase) | 1.14 (1.08 – 1.22)* |

| Time fully dilated | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.01)* |

| Parity | 0.87 (0.58 – 1.27) |

| Maternal age | 1.02 (0.97 – 1.07) |

| Day shift | Ref |

| Night shift | 1.24 (0.75– 2.06) |

| Instrument (forceps) | Ref |

| Instrument (ventouse) | 0.90 (0.54 – 1.50) |

| Ethnicity - Caucasian | Ref |

| Ethnicity - Black | 0.73 (0.03 – 6.35) |

| Ethnicity – Southeast Asian | 1.99 (0.69 – 5.57) |

| Ethnicity – other/unknown | 5.29 (1.27 – 24.59) |

| No epidural | Ref |

| Epidural | 1.20 (0.70 – 2.06) |

All cases of unsuccessful instrumental delivery are matched to cases of successful instrumental delivery within the same shift, where such a case exists. Where an unsuccessful instrumental delivery has no successful delivery within the same shift, it is not included in the analysis. Where multiple successful deliveries occur within the same shift as an unsuccessful delivery, all matches are included in the analysis. Model coefficients are expressed as odds ratios and 95% CIs.

p<0.001.

CI, confidence interval.

Associations that meet the threshold for statistical significance (alpha-level = 0.05) are shown in boldface.

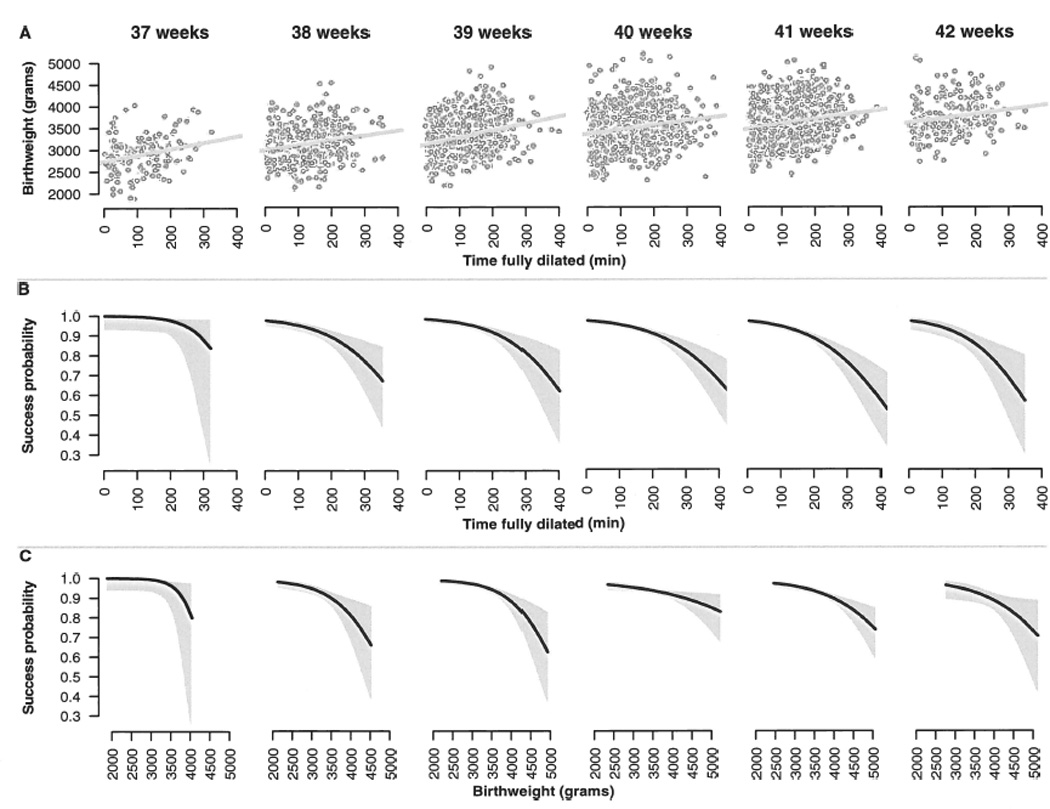

Table 4 shows the results of using linear regression to predict birth weight. Factors associated with higher birth weight are gestational age (p<0.001) and higher parity (p<0.01). Southeast Asian ethnicity is associated with lower birth weight (p<0.01). After refining the model using stepwise selection, approximately 22% of the variance in birth weight could be accounted for. This figure is not an artifact of linear regression: when using CART, a fully nonlinear method, only 24% of the variance in birth weight could be accounted for. This suggests that birth weight is difficult to predict accurately using information available at the time of delivery (Figure 2, Panel A).

Table 4.

Influence of Parameters Known to the Accoucheur Prior to Instrumental Delivery Attempt on Birth Weight

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Gestational age | 4.88 (4.35 – 5.48)* |

| Ethnicity- Caucasian | Ref |

| Ethnicity- Black | 0.72 (0.20 – 2.63) |

| Ethnicity- Southeast Asian | 0.10 (0.05 – 0.18)† |

| Ethnicity- Chinese | 0.47 (0.15 – 1.51) |

| Ethnicity- other | 0.55 (0.23 – 1.33) |

| Parity | 1.37 (1.11 – 1.69)† |

| Maternal BMI | 0.10 (0.10 – 1.20) |

| Maternal age | 0.98 (0.96 – 1.01) |

Multivariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression model. Model coefficients are expressed as odds ratios and 95% CIs.

p<0.001.

p<0.01.

CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

Associations that meet the threshold for statistical significance (alpha-level = 0.05) are shown in boldface.

Figure 2.

Panel A: Scatterplot and least-squares fit for birth weight versus time fully dilated, stratified by gestational age. Panels B and C: Estimated probability of successful instrumental delivery versus time fully dilated (B) and birth weight (C), stratified by gestational age. The black line shows the logistic-regression estimate; the grey area, a 95% confidence interval.

Women who underwent cesarean delivery without prior attempt at instrumental delivery had larger babies (OR=1.07 p<0.001), were older (OR=1.03 p<0.01) and were more likely to have had epidural analgesia (OR=1.46 p<0.001) (Table 5). Babies delivered by direct cesarean delivery, however, were not as large as those who had a failed instrumental delivery (3616g v 3711g, p<0.01).

Table 5.

Cases of Instrumental Delivery Compared to Cases of Direct Second-Stage Cesarean Delivery (where no instrument was applied)

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Birth weight (per 100g increase) | 1.07 (1.05 – 1.09)* |

| Maternal age | 1.03 (1.01 – 1.05)† |

| Ethnicity - Caucasian | Ref |

| Ethnicity - Black | 0.81 (0.24 – 2.03) |

| Ethnicity – Southeast Asian | 1.34 (0.86 – 2.00) |

| Ethnicity - Chinese | 0.93 (0.35 – 2.21) |

| Ethnicity – other/unknown | 0.88 (0.42 – 1.64) |

| Time at full dilation | 0.1- (0.1 – 1.00) |

| Maternal BMI | 1.00 (0.1 – 1.00) |

| Parity | 1.08 (0.94 – 1.24) |

| Accoucheur | 1.11 (0.95 – 1.30) |

| Delivery during daylight hours | 0.86 (0.70 – 1.04) |

| Epidural anaesthesia | 1.46 (1.18 – 1.81)* |

Multivariate analysis was performed using a binomial logistic regression model. Model coefficients are expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Levels of significance:

p<0.001;

p<0.01.

CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

Associations that meet the threshold for statistical significance (alpha-level = 0.05) are shown in boldface.

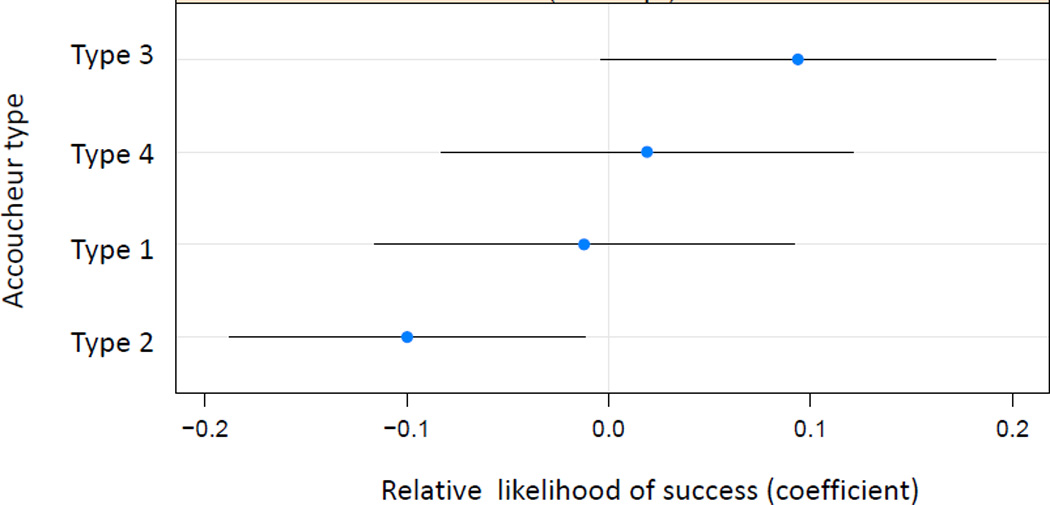

Greater seniority of the accoucheur appeared to adversely influence the chance of a successful instrumental delivery: type 2 accoucheurs had an overall failure rate of 5% v. 12% for type 3 or 4 accoucheurs (p<0.05). However, further analysis of the deliveries carried out by each accoucheur type demonstrated that the deliveries performed by type 3 or 4 (more experienced) accoucheurs were more likely to have higher birth weight (p<0.05) and to require rotation (p<0.001). After adjustment for these factors, type 3 accoucheurs are significantly more likely to succeed at instrumental delivery than type 2, their junior counterparts (Figure 3). There was no difference in the use of forceps v. ventouse depending on seniority of accoucheur.

Figure 3.

Likelihood of success in instrumental delivery classified by accoucheur type.

Finally, the analysis of the case-control subset identified birth weight and time fully dilated as the only significant predictors of failed instrumental delivery, regardless of whether logistic regression or CART was used. We therefore reran the logistic-regression model on the full cohort, first using only birth weight as a predictor, and then using only time fully dilated as a predictor (Figure 2). This allows us to estimate the overall probability of success versus the two major covariates (something that the case-control analysis cannot estimate properly). In Figure 2, the estimated probability of successful instrumental delivery is plotted against time fully dilated (Panel B) and birth weight (Panel C). In both panels, the models are stratified by gestational age, demonstrating that the same broad trends hold across 37–42 weeks. They show a clinically significant drop-off in the likelihood of success for larger babies, and for very long times fully dilated.

Discussion

We observed that increased birth-weight and increased duration of second stage are strongly associated with lack of success in instrumental delivery in both the unmatched and case-control analyses. Use of ventouse rather than forceps, and attempted rotation of the fetal head are associated with lack of success in the unmatched analysis only.

One possible interpretation of the associations between instrument selection, rotation, and instrumental delivery outcome is that their influence may be operator-dependent. It is recognized that fetal head malposition in the second stage is a risk factor for adverse labor outcomes (11). However, rotation of the fetal head is considered a controversial procedure by many obstetricians, despite data showing low complication rates (12, 13). While rotational instrumental delivery in our study had a higher rate of failure than non-rotational delivery, this was not the case for individual experienced operators, suggesting that more extensive experience of operative vaginal delivery would benefit trainee obstetricians. Although previous studies have concluded, as we do here in the full cohort analysis, that overall forceps delivery is more likely to achieve successful vaginal delivery than ventouse (14, 15), there is also evidence that operator preference for a particular instrument can affect the delivery outcome (16).

Although more experienced accoucheurs had the highest unadjusted rates of unsuccessful instrumental attempts, this is likely to be because more difficult deliveries are usually handled by more senior obstetricians. After adjusting for birth weight and the need for rotation, junior obstetrics trainees had the highest adjusted rates of unsuccessful instrumental delivery, indicating that increased training and experience are imperative.

Our data show that instrumental delivery is no less likely to be successful in older mothers. Despite this, we found an increased likelihood of progression directly to cesarean delivery in older mothers in the second stage. This may reflect obstetrician uncertainty regarding the likelihood of success of instrumental delivery in older mothers, as no data have previously been available to demonstrate success rates (17). It may also be considered less important to avoid cesarean delivery in older women, who are less likely to have further pregnancies.

A small number of previous studies have examined risk factors for failed instrumental delivery, yet none has been able to control for inter-accoucheur variability. A major strength of our study is its novel methodological approach, which reduces variation in individual accoucheur skill, differential thresholds in abandoning instrumental delivery for cesarean delivery, and ‘technique dependent’ variations including choice of instrument and need for rotation of the fetal head. While our findings are in general agreement with current literature (15, 18–20), our study population showed several important differences from those previously reported. In particular, our population had a higher rate of instrumental delivery (16.6%) compared to other studied populations (5–6% (15, 18, 20)). The use of forceps was also much higher in our study (58.2% v. 16.0%(15)), and rotational delivery was conducted within our study. This implies a greater experience and willingness to perform instrumental delivery within our center. The cesarean delivery rate of all attempted vaginal deliveries in our population was 13.8% (including 10.3% sections in the first stage of labor; Figure 1). The main limitations of our study include the difficulty in classifying deliveries where sequential instruments were used, and the inability from our database to identify a small number of babies presenting in the occipito-posterior position who may have been delivered by instrument without rotation. Additionally, is possible that the longer time in second stage during unsuccessful instrumental deliveries may be partially explained by the extra time required to perform cesarean delivery, but we are unable to distinguish this possibility from a clinical effect of having a prolonged second stage using the data available.

Experience from cohorts like ours with high rates of instrumental delivery and low rates of intra-partum cesarean delivery is especially important in light of current concerns regarding increasing cesarean delivery rates worldwide, and the drive to reverse this trend We demonstrate that once the need for instrumental delivery has been determined, the factors involved are reduced to a simple problem of mass and orientation to achieve delivery. Birth weight is difficult to estimate prior to delivery, however it is the major determinant of likelihood of success. Continued training in instrumental delivery for obstetricians is invaluable, as our study demonstrates significant improvement in success rates with increasing experience, ability to select the appropriate instrument, and ability to rotate the fetal head. Future research could focus on better methods of birth weight prediction, and on safe, effective training strategies for resident obstetricians.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Maternofetal Dyad and the Delivery Attempt, Both for the Full Data Set and Stratified By Outcome

| Characteristic | All Patients (N=3798) |

Successful Instrumentals (n=3552) |

Unsuccessful Instrumentals (n=246) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | 30.1 (19–40) | 30.1 (19–40) | 30.0 (18–40) |

| Maternal BMI | 25.0 (18–36) | 25.0 (18–36) | 25.2 (19–40) |

| Birth weight | 3487 (2610–4440) | 3460 (2600–4430) | 3709* (2945–4654) |

| Gestation | 39.9 (37–42) | 39.9 (37–42) | 40.1† (38–42) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 3352 | 3131 | 221 |

| Southeast Asian | 210 | 197 | 13 |

| Black | 43 | 41 | 2 |

| Chinese | 59 | 58 | 1 |

| Other/Unknown | 134 | 125 | 9 |

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 2008 | 1879 | 130 |

| 1 | 1545 | 1438 | 105 |

| 2 | 198 | 189 | 8 |

| 3 | 29 | 27 | 3 |

| 4+ | 18 | 19 | 0 |

| Time Fully Dilated | 132.3 (12–282) | 128.8 (12–275) | 132.5* (32–327) |

| Rotation Required | |||

| Yes | 365 | 317 | 48* |

| No | 3433 | 3235 | 198 |

| Instrument Used | |||

| Forceps | 2212 | 2076 | 136 |

| Ventouse | 1572 | 1476 | 96 |

| Both | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Epidural | |||

| Yes | 2338 | 2173 | 165* |

| No | 1146 | 1076 | 70 |

| Unknown | 314 | 303 | 11 |

| Accoucheur | |||

| Type 1 | 70 | 70 | 0 |

| Type 2 | 2760 | 2632 | 128* |

| Type 3 | 718 | 629 | 89 |

| Type 4 | 236 | 208 | 28 |

| Unknown | 14 | 13 | 1 |

Data are mean (95% confidence interval) or n. Numerical data are summarized by the mean and a coverage interval (in parentheses) spanning the 2.5–97.5 percentiles. Associations that meet the threshold for statistical significance (alpha-level = 0.05) are shown in boldface.

p<0.001.

p<0.01.

Acknowledgements

Abigail R Aiken is supported by a National Institute of Child Health and Development Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award under Grant No. 5 T32 HD007081-35, and by grant 5 R24 HD042849 awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. James G Scott is partially funded by a CAREER grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (DMS-1255187).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Majoko F, Gardener G. Trial of instrumental delivery in theatre versus immediate caesarean section for anticipated difficult assisted births. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012;10:CD005545. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005545.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiff E, Friedman SA, Zolti M, Avraham A, Kayam Z, Mashiach S, et al. A matched controlled study of Kielland's forceps for transverse arrest of the fetal vertex. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;21(6):576–579. doi: 10.1080/01443610120085500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander JM, Leveno KJ, Hauth JC, Landon MB, Gilbert S, Spong CY, et al. Failed operative vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1017–1022. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bbf3be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melamed N, Segev M, Hadar E, Peled Y, Wiznitzer A, Yogev Y. Outcome of trial of labor after cesarean section in women with past failed operative vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Mar 15; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Tanbo T, Abyholm T, Henriksen T. The impact of advanced maternal age and parity on obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(1):31–37. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1587-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuit E, Kwee A, Westerhuis ME, Van Dessel HJ, Graziosi GC, Van Lith JM, et al. A clinical prediction model to assess the risk of operative delivery. BJOG. 2012;119(8):915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma V, Colleran G, Dineen B, Hession MB, Avalos G, Morrison JJ. Factors influencing delivery mode for nulliparous women with a singleton pregnancy and cephalic presentation during a 17-year period. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKelvey A, Ashe R, McKenna D, Roberts R. Caesarean section in the second stage of labour: a retrospective review of obstetric setting and morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;30(3):264–267. doi: 10.3109/01443610903572109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahl R, Strachan B, Murphy DJ. Greentop Guideline 62; Operative Vaginal Delivery. UK: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone CJ, Olshen RA. Classification and Regression Trees. 2 ed. Belmont, California: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senecal J, Xiong X, Fraser WD. Effect of fetal position on second-stage duration and labor outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):763–772. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154889.47063.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Suhel R, Gill S, Robson S, Shadbolt B. Kjelland's forceps in the new millennium. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of attempted rotational forceps delivery. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(5):510–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tempest N, Hart A, Walkinshaw S, Hapangama D. A re-evaluation of the role of rotational forceps: retrospective comparison of maternal and perinatal outcomes following different methods of birth for malposition in the second stage of labour. BJOG. 2013;120(10):1277–1284. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Mahony F, Hofmeyr GJ, Menon V. Choice of instruments for assisted vaginal delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(11):CD005455. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005455.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Haroush A, Melamed N, Kaplan B, Yogev Y. Predictors of failed operative vaginal delivery: a single-center experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(3):308 e1–308 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abenhaim HA, Morin L, Benjamin A, Kinch RA. Effect of instrument preference for operative deliveries on obstetrical and neonatal outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134(2):164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhanjal MK, Kenyon A. Scientific Impact Paper No. 34: Induction of labour at term in older mothers. UK: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Kadri H, Sabr Y, Al-Saif S, Abulaimoun B, Ba'Aqeel H, Saleh A. Failed individual and sequential instrumental vaginal delivery: contributing risk factors and maternal-neonatal complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(7):642–648. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gopalani S, Bennett K, Critchlow C. Factors predictive of failed operative vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheiner E, Shoham-Vardi I, Silberstein T, Hallak M, Katz M, Mazor M. Failed vacuum extraction. Maternal risk factors and pregnancy outcome. J Reprod Med. 2001;46(9):819–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]