Abstract

Background:

We compared i-gel and ProSeal laryngeal mask airway (PLMA) regarding time taken for insertion, effective seal, fiberoptic view of larynx, ease of Ryle's tube insertion, and postoperative sore throat assessment.

Materials and Methods:

In a prospective, randomized manner, 48 adult patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists I-II of either gender between 18 and 60 years presenting for a short surgical procedure were assigned to undergo surgery under general anesthesia on spontaneous ventilation using either the i-gel or PLMA. An experienced nonblinded anesthesiologist inserted appropriate sized i-gel or PLMA in patients using standard insertion technique and assessed the intraoperative findings of the study regarding regarding time taken for respective device insertion, effective seal, fiberoptic view of larynx, ease of Ryle's tube insertion, and postoperative sore throat assessment. Postoperative assessment of sore throat was done by blinded anesthesia resident.

Results:

The time required for insertion of i-gel was lesser (21.98 ± 5.42 and 30.60 ± 8.51 s in Group I and Group P, respectively; P = 0.001). Numbers of attempts for successful insertions were comparable and in majority, device was inserted in first attempt. The mean airway leak pressures were comparable. However, there were more number of patients in Group P who had airway leak pressure >20 cm H2O. The fiberoptic view of glottis, ease of Ryle's tube insertion, and incidence of complications were comparable.

Conclusion:

Time required for successful insertion of i-gel was less in adult patients undergoing short surgical procedure under general anesthesia on spontaneous ventilation. Patients with airway leak pressure >20 cm H2O were more in PLMA group which indicates its better suitability for controlled ventilation.

Keywords: Airway leak pressure, i-gel, PLMA, time for insertion

Introduction

Supraglottic airway devices (SADs) have been widely used as an alternative to tracheal intubation during general anesthesia.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] They are easily inserted, better tolerated, with lesser hemodynamic changes, have favorable respiratory mechanics, and decreased airway morbidity.[8,9,10,11] The current guidelines on cardiopulmonary resuscitation also recommend SADs as an alternative to tracheal intubation.[12,13]

The Proseal™ laryngeal mask airway (PLMA) (intavent Orthofix, Maidenhead, UK) and the i-gel airway (Intersurgical Ltd, Wokingham, Berkshire, UK) are the two SADs which provide higher airway leak pressure than the classic LMA (cLMA) and can be used for spontaneous as well as positive pressure ventilation (PPV).[14,15] Both these devices have separate channel for gastric tube insertion and are recommended for spontaneous as well as controlled ventilation.

The i-gel airway is a novel supraglottic airway management device having a noninflatable anatomical seal of the pharyngeal, laryngeal, and perilaryngeal structures. It avoids compression trauma that can occur with inflatable SADs like PLMA.[16] A supraglottic airway without an inflatable cuff has several advantages including easier insertion and minimal risk of tissue compression. Though studies have been done comparing i-gel with PLMA, we proposed to compare the two devices, especially with regards time taken for insertion, number of attempts, effectiveness of seal and occurrence of postoperative sore throat apart from other parameters of their efficacy.

Materials and Methods

This prospective, randomized, comparative study was conducted after obtaining approval from the institutional ethical committee. American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I and II of either gender aged 18-60 years, with body mass index 18-30 kg m−2 undergoing elective short surgical procedures (duration between 30 and 120 min) requiring general anesthesia without muscle relaxation were included. Patients with increased risk of pulmonary aspiration, completely edentulous patients, anticipated difficult airway, and surgeries involving the head and neck were excluded from the study.

On the basis of the previous study by Singh et al.,[17] it was estimated that a total of 48 patients were needed for a power of 80% with an alpha error of 5% to detect a statistically significant difference in mean airway leak pressure of 5 cm H2O.

After taking consent, randomization into one of the two groups was done. The two groups were as follows: Group I: i-gel; Group P: ProSeal LMA.

Patients in Group I, appropriate sized i-gel (size 3: Body weight between 30 and 60 kg; size 4: 50-90 kg; size 5: >90 kg) and in Group P, PLMA (size 3 in females and size 4 for males) was chosen as airway device for the surgery.

All patients were kept nil per oral 6 h for solids and 2 h for clear fluids prior to the surgery.

Inside the operating room, standard monitoring was commenced using five lead electrocardiogram, SpO2, automated noninvasive arterial pressure monitoring by oscillometry and capnography. A peripheral intravenous line was secured in the upper limb with an appropriate infusion. All patients were preoxygenated with 100% oxygen for 3 min. An intravenous bolus of fentanyl 2 μg kg−1 was given after the start of preoxygenation. Anesthesia was induced with propofol 3 mg kg−1 and anesthetic depth was deepened with 2% isoflurane in oxygen using bag mask ventilation. Patient was kept in sniffing position prior to device insertion. An additional dose of propofol was used to achieve adequate depth of anesthesia prior to the device insertion which was accomplished by assessing jaw relaxation, loss of verbal contact, and minimal alveolar concentration of isoflurane at 1. Then, an appropriate sized prior lubricated (water based jelly) i-gel and PLMA were inserted in Group I and Group P, respectively by nonblinded consultant anesthesiologist who had >3 years experience. A lubricated Ryle's tube (12 F) was placed into the stomach through the gastric channel and number of attempts for insertion was limited to two.

Anesthesia was maintained with oxygen, nitrous oxide, and isoflurane in spontaneous ventilation using semi closed adult circle system with the carbon dioxide absorber in place. The cuff of PLMA was inflated with air and maintained at a pressure of ≤60 cm H2O using cuff pressure manometer throughout surgery.

Proper placement of the inserted device was confirmed by square wave capnograph trace, normal chest movement, and ingress and egress of gases by auscultation in front of neck of the patient. The factors considered for the failure for the proper placement of the device were failure to introduce into the pharynx, ineffective ventilation (inadequate chest rise, abnormal capnogram), drop in SpO2<95% while insertion, time taken to insert device exceeding 60 s, and malposition. Initial two attempts were allowed for one device before insertion was considered as a failure. In case of failure of the device, only first attempt of the next device was used. If both devices were failed, further management left to the discretion of the concerned anesthesia team.

Time for successful placement the device, number of attempts for placement, airway leak pressures, fiberoptic grading of larynx, and ease of Ryle's insertion were assessed and noted by anesthesia consultant. During the insertion of the device, the number of attempts for the successful insertion and time taken for successful insertion of device (timed from the picking up the device till the appearance of capnographic trace) was recorded.

Laryngeal view was assessed by passing fiberoptic bronchoscope through the ventilating lumen of the device and graded as per percentage of glottic opening scale as described by Levintan et al.[18] [Grade I: Glottis fully visible; Grade II: >50% of glottis visible; Grade III: <50% of glottis visible; Grade IV: Glottis not visible].

Airway leak pressure was defined as the airway pressure (PL) at which the leak was heard with fresh gas flow at 5 L min−1 and adjustable pressure limiting (APL) valve closed at 40 cm H2O.

In the anesthesia machine (Datex-Ohmeda Aestiva/5) with inbuilt aneroid pressure gauge, the fresh gas flow rate was set at 5 L min−1 and APL valve of the circle system was closed at 40 cm H2O. Then, trachea was continuously auscultated in the anterior neck for the audible leak, while airway pressure was monitored from the pressure gauge of the anesthesia machine. A maximum of 40 cm H2O of airway pressure was allowed during the leak check procedure.

At the end of surgery all anesthetics were tapered off. Once the patient was wide awake and responsive, the i-gel or PLMA was removed without oropharyngeal suctioning. Presence of visible blood stains over the device was noted. Patients requiring oropharyngeal airway/oropharyngeal suction in the perioperative period were excluded from the further evaluations. All the patients were interviewed for sore throat at 6th and 18th immediate postoperative hour by blinded anesthesia resident (primary investigator).

Postoperative sore throat was graded as described by Figueredo et al.,[19] as follow:

Grade 0: No sore throat

Grade 1: Mild sore throat — Pain on swallowing solids

Grade 2: Moderate sore throat — Pain on swallowing liquids

Grade 3: Severe sore throat — Pain even on swallowing saliva.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 for Windows. Time for successful insertion of the device and mean airway leak pressure were compared between the groups using independent samples ‘t’ test. The number of attempts for successful device insertion and number of patients with airway leak pressure above as well as below were compared using chi-square test. Fiberoptic view through the device, ease of Ryle's tube insertion, blood on device after removal, and postoperative sore throat assessment were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. A P value <0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

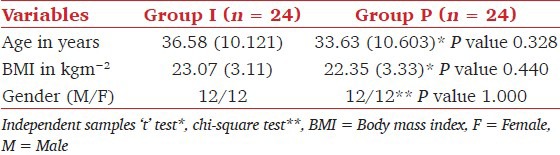

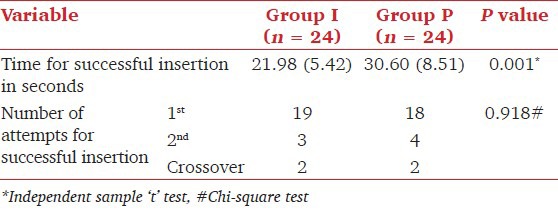

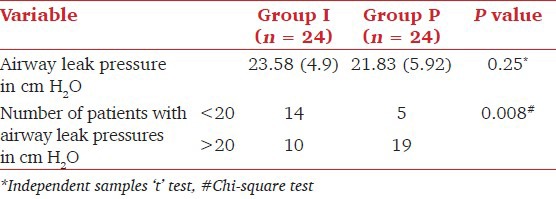

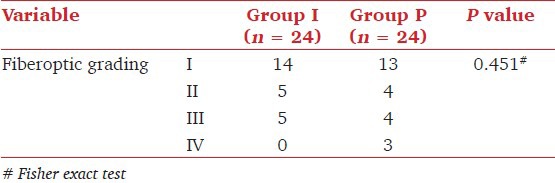

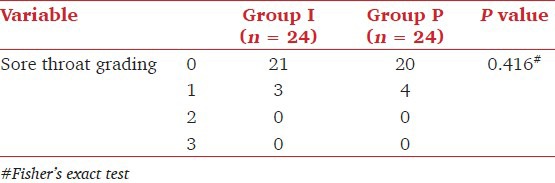

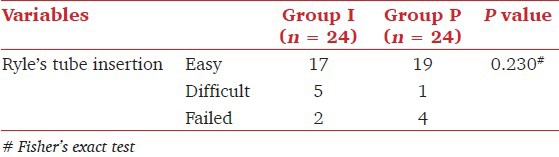

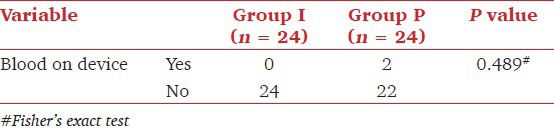

Patient characteristics in the 48 patients were comparable among the groups [Table 1]. Time for successful insertion of i-gel was significantly lesser than PLMA (P = 0.001). The numbers of attempts for successful insertion were comparable (P = 0.918) and two patients in each group required cross over due to failure for successful insertion in first two attempts [Table 2]. Mean airway leak pressures were comparable between the groups (P = 0.25). The comparison of number of patients with airway leak pressure above as well as below 20 cm H2O showed significant difference (P = 0.008) [Table 3]. Fiberoptic view of larynx through the device, ease of Ryle's tube insertion, blood stained device after removal, and postoperative sore throat assessments, among both groups were comparable [Tables 4–7].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics: Data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) for age and body mass index; and absolute number for gender

Table 2.

Time for successful insertion of the device [data are in mean (standard deviation)] and number of attempts for successful insertion (data are in absolute numbers)

Table 3.

Airway leak pressure [data are in mean (standard deviation)] and number of patients with airway leak pressure above and below 20 cm H2O (data are in absolute numbers)

Table 4.

Fiberoptic view of glottis

Table 7.

Sore throat assessment at 6th and 18th postoperative h

Table 5.

Ease of Ryle's tube insertion

Table 6.

Visible blood on device after removal

Discussion

We found that mean time required for successful insertion of i-gel (21.98 s) was significantly shorter than PLMA (30.60 s). In previous studies, the time required for i-gel insertion was lesser compared to other SADs with mean time for i-gel insertion was 12-20 s.[17,20,21,22] This could be due to some time required for cuff inflation of PLMA after its insertion. The two groups were comparable with regards to the number of attempts. Two patients in each group had unsuccessful in first two attempts, but crossover of the device was successful in first attempt. In these crossover patients, successfully inserted device time for placement only was taken into consideration.

The effective airway leak pressure is essential especially using SADs in patients with increased respiratory resistance, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and obese patients. Since, a higher airway leak pressure increases the likelihood that a preset tidal volume can be applied during PPV. Studies on SADs suggest that mean peak airway pressure of more than 20 cm H2O increases the risk of leakage with resultant insufficient ventilation and increased risk of aspiration.[23,24] We found that mean airway leak pressure was comparable between the groups (23.58 and 21.83 cm H2 0 in Group I and Group P, respectively). We also observed that PLMA group had significantly higher number of patients (19 vs. 10) with leak pressure above 20 cm H2O (P = 0.008). Hence, PLMA may be better suited for PPV than the i-gel. However patients in our study were on spontaneus ventilation, hence future studies need to assess suitability of SADs for PPV with leak pressures above 20 cms of H2O.

The various clinical studies have given different grading system for laryngeal view.[25,26] A good laryngeal view may be helpful for fiberoptic intubation through these devices. Most of the previous studies have shown little or no correlation between fiberoptic position and function of SADs.[25,26] We followed grading system used by Levintan et al.,[18] and found that both groups were comparable with regard to fiberoptic view of larynx. Most of the patients had grade 1 view (14 vs. 13; Group I vs. Group P), but only three patients in group-P had grade IV view even though we could successfully ventilate these patients. This could be due to folding of PLMA cuff while insertion.

The overall success rate for Ryle's tube insertion was comparable between the two groups in our study. It is similar to success rate achieved with most studies on SADs with drain tube. We made no attempt, however, to assess the efficacy of the drain tube in preventing inflation of stomach or aspiration of gastric contents. In size 4 i-gel, the drain tube is significantly smaller than in a size 4 PLMA (FG12 compared with FG 16). The PLMA has been investigated in previous study by Borkowski et al and was found to offer significant protection against aspiration.[27] No such studies have been performed for the i-gel and whether the smaller drain tube is adequate remains still unproven. The incidence of regurgitation and aspiration with the i-gel is unknown. The PLMA has been associated with three confirmed cases of regurgitation.[28] Even if protection is incomplete, the presence of a drain tube allows early identification of regurgitation and prompt response to prevent or minimize aspiration.

Postoperative adverse events are not uncommon with SADs. To limit these complications, we limited two insertion attempts for each device for successful placement, and following failure of these attempts, only one attempt was allowed with crossover device and only two attempts were used for Ryle's tube insertion. Also we avoided oropharyngeal suctioning and maitianed the cuff pressure of PLMA below 60 cm H2O throughout the surgery. Previous studies observed an incidence of blood stained on the device of 1%-15%.[29] In our study, only two patients in Group P has blood stained device and none i-gel group. This may be due to the gel filled cuff causing less trauma and or pressure damage to the oropharyngeal mucosa and first successful attempt for most of the insertions.

The causes of postoperative sore throat after general anesthesia using SADs are dependent on the depth of anesthesia, the method of insertion, number of insertion attempts, the mode of ventilation used, and the duration of anesthesia and on the type of postoperative analgesia provided.[30,31] We intended to control some of the above-mentioned variables by limiting insertion attempts, duration of anesthesia, mode of ventilation, and monitoring cuff pressures of PLMA. Postoperative use of analgesics can also modify severity or incidence of sore throat. But in our study, we did not assess the effect of analgesics on this issue. Perhaps if we could have formulated the protocol for postoperative analgesics, the study result might have showed the true incidence and severity of sore throat. Majority of the patients did not have postoperative sore throat which could be due to the high success rate in first insertion attempts in both the groups.

One of the major limitations of our study was our inability to blind the anethesiologist inserting the device to group allocation.

Hence to conclude, ease and shorter times to successful insertion were observed with i-gel. PLMA had higher airway leak pressure which may be better suited for controlled ventilation. Both devices are comparable with respect to fiberoptic view of larynx, ease of Ryle's tube insertion, and incidence of sore throat.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Boehler M, Puhringer F. Positive pressure ventilation with the Proseal versus classic laryngeal mask airway: A randomized, crossover study of healthy female patients. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1351–3. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Brimacombe L. A comparison of the laryngeal mask airway Proseal and the laryngeal tube airway in paralyzed anesthetized adult patients undergoing pressure-controlled ventilation. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:770–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200209000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook TM, Cranshaw J. Randomized crossover comparison of Proseal laryngeal mask airway with laryngeal tube sonda during anesthesia with controlled ventilation. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:261–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldmann K, Roettger C, Wulf H. The size 1(1/2) Proseal laryngeal mask airway in infants: A randomized, crossover investigation with the classic larynageal mask airway. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:405–10. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000194300.56739.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Gil M, Brimacombe J, Garcia G. A randomized non crossover study comparing the proseal and classic laryngeal mask airway in anaesthetized children. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:827–30. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldmann K, Jacob C. A randomized crossover comparison the size 2.5 laryngeal mask airway Proseal versus laryngeal mask airway classic in pediatric patients. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1605–10. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000152640.25078.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldmann K, Jacob C. Size 2 laryngeal mask airway: A randomized crossover investigation with the standard laryngeal mask airway in pediatric patients. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:385–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyer RA, Llewellyn RL, James MF. Total i.v. anesthesia with propofol and the laryngeal mask for orthopedic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:123–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cork RC, Depa RM, Standen JR. Prospective comparison of use of the laryngeal mask and endotracheal tube for ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:719–27. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199410000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatt SB, Kendall AP, Lin ES, Oh TE. Resistance and additional inspiratory work imposed by the laryngeal mask airway. A comparison with tracheal tubes. Anesthesia. 1992;47:343–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins PP, Chung F, Mezei G. Post operative sore throat after ambulatory surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:582–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolan JP, Deakin CD, Soar J, Bottiger BW, Smith G. European Resuscitation Council. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005. Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S39–86. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabott A, Beringer R. The i-GEL supraglottic airway: A potential role for resuscitation.? Resuscitation. 2007;73:161–2. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brain AI, Verghese C, Strube PJ. The LMA ‘Proseal’- a laryngeal mask with an oesophageal vent. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:650–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/84.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.I-gel user guide. 2007. [Last accessed date 2014 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.I-gel.com.- I-gelinstruction manual .

- 16.Levitan RM, Kinkle WC. Initial anatomic investigation of I-gel airway: A novel supraglottic airway without inflatable cuff. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1022–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh I, Gupta M, Tandon M. Comparison of clinical performance of I-GEL with LMA Proseal in elective surgeries. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:302–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levintan RM, Ochroch EA, Kush S, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Assessment of airway visualization: Validation of the percent of glottic opening (POGO) scale. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:919–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02823.x. Respected Sir/Madam on internet, last accessed date not coming with article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueredo E, Martinez, Pintanel T. A comparison of the Proseal laryngeal mask and the laryngeal tube in spontaneously breathing anaesthetized patients. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:600–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200302000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uppal V, Gangaiah S, Fletcher G, Kinsella J. Randomised crossover comparison between the i-gel and the LMA-Unique in anaesthetized, paralysed adults. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:882–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatward JJ, Cook TM, Seller C, Handel J, Simpson T, Vanek V, et al. Evaluation of the size 4 I-gel airway in one hundred non-paralysed patients. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:1124–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wharton NM, Gibbison B, Gabbott DA, Haslam GM, Muchatuta N, Cook TM. I-gel insertion by novices in manikins and patients. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:991–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel B, Bingham R. Laryngeal mask airway and other supraglottic airway devices in paediatric practice. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2009;9:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein RH, Ferouz F, Jenkins MA. Airway sealing pressures of the laryngeal mask airway in paediatric patients. J Clin Anesth. 1996;8:93–8. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inagawa G, Okuda K, Miwa T, Hiroki K. Higher airway seal does not imply adequate positioning of laryngeal mask airways in paediatric patients. Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12:322–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Zundert A, Brimacombe J, Kamphuis R, Haanschoten M. The anatomical position of three extraglotic airway devices in patients with clear airways. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:891–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borkowski A, Perl T, Heuer J, Timmermann A, Braun U. The applicability of proseal laryngeal mask airway for laparotomies. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2005;40:477–86. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma B, Sahai C, Bhattacharya A, Kumar VP, Sood J. Proseal laryngeal mask airway: A study of 100 consecutive cases of laparoscopic surgery. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:467–72. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uppal V, Fletcher G, Kinsella J. Comparison of the i-gel with the cuffed tracheal tube during pressure-controlled ventilation. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:264–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peirovifar A, Eydi M, Mirinejhad MM, Mahmoodpoor A, Mohammadi A, Golzari SE. Comparison of postoperative complication between laryngeal mask airway and endotracheal tube during low-flow anesthesia with controlled ventilation. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:601–5. doi: 10.12669/pjms.292.2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mokhtar AM, Choy CY. Postoperative sore throat in children: Comparison between proseal LMA and classic LMA. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2013;22:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]