Abstract

Members of racial/ethnic minority groups are less likely than Caucasians to access mental health services despite recent evidence of more favorable attitudes regarding treatment effectiveness. The present study explored this discrepancy by examining racial differences in beliefs about how the natural course and seriousness of mental illnesses relate to perceived treatment effectiveness. The analysis is based on a nationally representative sample of 583 Caucasian and 82 African American participants in a vignette experiment about people living with mental illness. While African Americans were more likely than Caucasians to believe that mental health professionals could help individuals with schizophrenia and major depression, they were also more likely to believe mental health problems would improve on their own. This belief was unrelated to beliefs about treatment effectiveness. These findings suggest that a belief in treatment effectiveness may not increase service utilization among African Americans who are more likely to believe treatment is unnecessary.

Keywords: African Americans, Beliefs, Mental health, Treatment effectiveness

Several psychiatric epidemiological studies have demonstrated that voluntary, professional mental health services are underutilized by the general public (e.g., Kessler et al.1994; Wang et al. 2005). Even among people in the general population who perceive a need for mental health services, as many as 41% do not seek help from mental health pro-fessionals (Mojtabai et al. 2002). Recent research shows that service use among the general population has increased somewhat; however, there is still a discrepancy between need for treatment and actual utilization, and this difference is even more marked for ethnic and racial minorities (Wang et al. 2005). Specifically, African Americans have been found to utilize fewer mental health services than Caucasians (Kessler et al. 1994; Neighbors 1988; Reiger et al.1993; Wang et al. 2005). These findings exist across a wide range of disorders including depression (Sussman et al.1987), lifetime mood disorder (Kessler et al. 1994), anxiety disorders (Kessler et al. 1994; Neal and Turner 1991), and serious mental illness (Kessler et al. 1996).

A variety of possible explanations for this racial/ethnic disparity have been offered in the literature and range from well-documented inequalities in the quality of care received (Smedly et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2000) and socioeconomic status (Muntaner 1999) to psychosocial explanations of cultural mistrust (Nickerson et al. 1994; Whaley 2001a, b), and stigma (Anglin et al. 2006; Cooper-Patrick et al. 1999; Sanders Thomson et al. 2004; Schnittker et al. 2000). Differential conceptions of mental illness and expectations about treatment have received less empirical attention (but see Snowden 1999). Yet, implicit in these explanations is the notion that groups with more negative views of the treatment system and its effectiveness would naturally seek treatment less often than individuals whose impressions of these systems were more positive. Given both the current disparities in quality of care and the historical abuses African Americans have encountered in treatment systems (Jones 1981), it seems plausible that patient preferences and beliefs could stand as reasonable explanations for usage differences between African Americans and Caucasians.

Very few studies have examined whether there are racial differences in beliefs about the effectiveness of mental health treatment (but see e.g., Cooper-Patrick et al. 1997; Sanders Thomson et al. 2004). Some research suggests that African Americans are less likely than Caucasians to recommend professional treatment options to a hypothetical person suffering from mental health problems (Schnittker et al. 2000). However, two recent nationally representative studies (Diala et al. 2001; and Schnittker et al. 2005) show that African Americans in the general public reported more positive attitudes than Caucasians about whether they would feel comfortable seeking mental health care. Schnittker et al. (2005) examined beliefs and expectancies about medical treatment and mental health treatment specifically. They did not find significant differences between African Americans and Caucasians in beliefs and expectations about medical care for physical problems; however, they did find robust racial differences regarding mental health care. There were significantly stronger predispositions among African Americans to seek treatment if they were not “feeling calm and peaceful” or “not having lots of energy”. Furthermore, Schnittker and colleagues found that African Americans hypothetically feeling downhearted were significantly more likely than Caucasians to expect that seeking treatment would improve their quality of life and relationships with their families, help them feel better about themselves, and cure them. Thus, a disjuncture arises: while Black Americans in the general public hold more positive beliefs about mental health treatment and its effectiveness than Caucasians, they are still less likely to seek voluntary, outpatient mental health services.

This discrepancy may potentially be explained by considering another factor that affects service utilization. The decision to seek help is not only linked to whether the treatment is believed to be efficacious, but is also more likely when a mental health problem is considered unlikely to improve without professional intervention (cited in Cauce et al. 2002). These beliefs about the untreated course of illness may differ between racial groups. Empirical studies have not specifically addressed this question, but there is relevant related evidence for racial differences in the conceptualization of mental illness. For example, Schnittker et al. (2000) found that whereas African Americans were more likely than Caucasians to believe that mental illness is a result of “bad character,” they were less likely to endorse genetic and other biological explanations. We posit that these differences in causal beliefs might be related to beliefs about the seriousness and natural course of mental illnesses and consequently to beliefs about the necessity of treatment. Furthermore, we believe this might explain why African Americans utilize treatment less often than Whites, even as they hold more positive expectations about treatment effectiveness. That is, believing treatment is efficacious will not lead to actual help-seeking if treatment is not also deemed to be necessary.

This paper has two purposes. First, we examine whether Schnittker et al.’s (2005) recent finding of more positive expectations about professional mental health treatment among African Americans can be replicated using a different method—one that employs vignette descriptions of people with specific mental illnesses rather than general survey items about hypothetical symptoms. Second, to elucidate reasons for racial differences in treatment seeking, we examine differences between African Americans and Caucasians in their beliefs about the natural course and seriousness of mental illness. Finally, we examine whether relationships between perceived treatment effectiveness and beliefs about the natural course and seriousness of illness are different for African Americans compared to Caucasians.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

The goal of the parent study was to assess the impact of genetic attributions for mental illness on stigmatizing attitudes in a multi-ethnic sample of Americans (African-Americans, Caucasians, Mexican-Americans, Chinese-Americans and Puerto Ricans). Pilot telephone interviews were conducted with the general public by professional interviewers employed and trained by a professional survey firm to create the final telephone survey interview, which was modified to eliminate questions that were confusing to respondents.

For the data reported in this paper, the target population comprised persons aged 18 and older, living in households with telephones, in the continental United States. The sampling frame was derived from a list-assisted, randomdigit-dialed (RDD) telephone frame. A respondent was randomly selected from among all adults in the household, eligibility was determined, and informed consent obtained. When necessary, repeated calls were made to selected telephones at different times and days of the week. Interviews were conducted with 1,241 adults between June 2002 and March 2003. Interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, Mandarin and Cantonese and averaged 20 minutes. The sample was stratified to oversample Puerto Ricans, Chinese Americans and people with a family history of psychiatric hospitalization. Using estimation procedures of the Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO) (1982), the response rate was 62%, which is in accord with recent trends in response rates for RDD survey research (Babbie 2007). The response rate is equal to the screening completion rate, i.e., the proportion of units where a decision has been reached as to whether or not a unit is eligible, multiplied by the interview completion rate, that is, the proportion of screened eligible responses who completed an interview (CASRO 1982).

All results are weighted (1) to account for poststratification adjustment to national census counts by race/ethnicity and (2) to reflect the different probabilities of selection according to race/ethnicity and family history of psychiatric hospitalization that were built in to the complex survey design. To calculate statistical tests, survey commands in STATA were used to estimate standard errors for complex survey designs. Institutional review board approval was obtained for the study.

Of the total number of African American (118) and Caucasian (913) respondents, we focused our analyses on those who responded to vignettes about mental illness (N = 665). Since the number of cases used in subsequent analyses varies due to missing data, we use N = 573 for Caucasian and N = 80 for African American, as this represents the smaller of the sample sizes available to us. With alpha set at p < .05, power to detect effect sizes of .5 (defined as “medium” by Cohen 1988), .4 and .3 are >.99, .92 and .71, respectively. Thus with respect to power we are very confident that we have the power to detect medium and even somewhat smaller effects using this sample. To evaluate sample selection bias, we compared the sample with data from the 2000 Census separately for African Americans and Caucasians. Correspondence is quite close for both African Americans and Caucasians with respect to age and income (details available on request from corresponding author). Our sample over-represents women in both groups (64% of African American analysis sample compared to 52.5% of the census; 65% of Caucasian analysis sample compared to 51% of census); and also includes more highly educated African Americans (32.7% of analysis sample 25 years and over are college graduates vs. 20% of the Black census population).

The African American and Caucasian sub-samples were similar to each other in terms of gender proportion and educational attainment. African Americans were significantly younger (F (1, 669) = 22.15, p < .001) and reported lower incomes (F (1, 669) = 8.17, p < .01) than Caucasians. These demographic variables will be controlled in the multivariate analyses.

The Vignettes

Respondents were randomly assigned to hear one vignette describing a hypothetical person with major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or one of a number of physical illnesses. Following the vignettes, respondents were queried about their attitudes, opinions and beliefs about the described person. We focus on 82 African American and 583 Caucasian respondents who were randomly assigned to either a major depressive disorder or schizophrenia vignette description (N = 665). The vignette subject’s gender, SES (three levels), and cause of the illness (strongly genetic, partly genetic, not genetic) were randomly varied; and the vignette subject’s race/ethnicity was matched to that of the respondent. Below is one version of the vignette with underlined text indicating characteristics that were varied.

Imagine a person named John. He is a single, 25-year old White man. Since graduating from high school, John has been steadily employed and makes a decent living. Usually, John gets along well with his family and co-workers. He enjoys reading and going out with friends. About a year ago, John started thinking that people around him were spying on him and trying to hurt him. He became convinced that people could hear what he was thinking. He also heard voices when no one else was around. Sometimes he even thought people on TV were sending messages especially to him. After living this way for about six months, John was admitted to a psychiatric hospital and was told that he had an illness called “schizophrenia.” He was treated in the hospital for two weeks and was then released. He has been out of the hospital for six months now and is doing OK. Now, let me tell you something about what caused John’s problem. When he was in the hospital, an expert in genetics said that John’s problem was due to genetic factors. In other words, his problem had a very strong genetic or hereditary component.

Measures

Dependent Variables

Three single item measures were used as dependent variables. Professional can help. “In your opinion, how likely is it that a mental health professional, like a psychiatrist, psychologist or social worker can help with the problems like NAME has? Improve without professional help. “In your opinion, how likely it is that a problem like NAME has can improve without the help of a mental health pro-fessional? The response options for these two items were: Would you say this is… “very likely,” “somewhat likely,”“not very likely,” or “not likely at all.” Seriousness. “How serious would you consider (his/her) problem to be? Do you think it is… “very serious,” “somewhat serious,” “not very serious,” or “not serious at all.”

Independent Variable

Race was measured by the self-identification of the respondent as “Black or African American” (1) or “White” (0). Other race/ethnic groups were not included in the current analyses.

Covariates

We control for sociodemographic variables that were found to be correlates of race that could account for any racial differences in attitudes about mental illness and its treatment. These were assessed before the vignette was presented. Demographic variables include: gender; age (in years); education (less than high school = 1; high school or technical school = 2; some college = 3; college grad or more = 4); and household income (under $20,000 = 1; $20,000 to $40,000 = 2; $40,000 to 60,000 = 3; $60,000 to $80,000 = 4; $80,000 or more = 5).

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of African American and Caucasian responses to the item about mental health pro-fessional effectiveness and the two items about whether mental illness conditions are serious and will not improve on their own. Row proportions are based on weighted counts. Results indicate that African Americans were significantly more likely than Caucasians to believe that a mental health professional could help with a mental illness condition and that the said illness would improve on its own. The distribution of responses to the item about the severity of mental illness was not statistically different for African American and Caucasian respondents.

Table 1.

Percentages of African Americans and Caucasians endorsing dependent variables

| Race | Dependent variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A mental health professional can help the condition | ||||

| χ2 (2) = 8.12*** | Not likely at all/Not very likely | Somewhat likely | Very likely | |

| Caucasian | 7.7% (n = 46) | 38.8% (n = 224) | 53.5% (n = 313) | |

| African American | 1.3% (n = 1) | 34.2% (n = 28) | 64.5% (n = 53) | |

| How serious is the problem? | ||||

| χ2 (2) = 6.76 | Not serious at all/Not very serious | Somewhat serious | Very serious | |

| Caucasian | 4.9% (n = 29) | 49.5% (n = 278) | 45.6% (n = 272) | |

| African American | 9.5% (n = 8) | 38.0% (n = 30) | 52.5% (n = 42) | |

| Will the condition improve on its own? | ||||

| χ2 = 13.02** | Not likely at all | Not very likely | Somewhat likely | Very likely |

| Caucasian | 34.8% (n = 203) | 40.7% (n = 232) | 18.5% (n = 107) | 6.0% (n = 39) |

| African American | 37% (n = 29) | 26% (n = 22) | 20.9% (n = 16) | 16.1% (n = 14) |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .06

We used bivariate Pearson product–moment correlations to examine the relationships among the dependent variables for the combined study sample and separately for African American and Caucasian respondents. The results presented in Table 2 show that for the full sample, the belief in the effectiveness of mental health professionals was significantly negatively related to the belief that mental health conditions will improve on their own. A statistically significant relationship was present among Caucasian respondents but not among African Americans. For the full sample, the belief in the effectiveness of mental health professionals was significantly positively related to the belief that mental health conditions are serious. Again, this statistically significant positive correlation was found for Caucasian respondents but not for African American respondents (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between dependent variables for combined sample and stratified by race

| A mental health professional can help the condition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | Caucasian | African American | |

| Condition will improve on its own | −.18** | −.25** (n = 576) | −.03 (n = 81) |

| Seriousness of condition | .12* | .16* (n = 573) | −.02 (n = 80) |

p < .001

p < .0001

We conducted multiple linear regression analysis to examine whether racial differences found at the bivariate level would remain when controls for potential confounding variables were added. Belief in the effectiveness of mental health professionals was the dependent variable. Race, beliefs about the severity of illness, and beliefs about the course of illness were independent variables. We also controlled for the covariates of age, gender, family income, education, and vignette type (i.e. schizophrenia or depression).

Table 3 shows the results of four regression equations predicting respondent beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. We did not include family income, education, or the vignette version (schizophrenia vs. major depression) in the equations shown in Table 3, as none of these variables significantly predicted the perceived effectiveness oftreatment after age and gender were controlled. In Eq. 1, race/ethnicity was entered as a single independent variable. African Americans were more likely than Caucasians (b = .18, t(662) = 2.55, p < .05) to believe that mental health professionals can help a person with mental illness conditions. Equation 2 shows controls for age, gender, the perception that the condition will improve on its own, and the seriousness of the condition. Respondents who were younger (b = −.004, t(639) = −2.44, p < .05), and female (b = .20, t(639) = 3.68, p < .001), believed that the condition would not improve on its own (b = −.12, t(639) = − 4.13, p < .001) saw the condition as more serious (b = .13, t(639) = 2.51, p < .05), were more likely to believe that mental health professionals can help a person with mental illness. While these controls produce a small reduction in the magnitude of the effect of race (b = .15) the coefficient remains significant.

Table 3.

Summary of regression analyses for mental help effectiveness

| Variables | A mental health professional can help the condition |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation 1 |

Equation 2 |

Equation 3 |

Equation 4 |

|||||

| b | s.e. | b | s.e. | b | s.e. | b | s.e. | |

| Main effect | ||||||||

| African American | .18* | .07 | .15* | .08 | −.16 | .15 | .79* | .37 |

| Demographic controls | ||||||||

| Age | – | −.004** | .00 | −.004* | .00 | −.004** | .00 | |

| Gender (Women = 1) | – | .16** | .05 | .16** | .06 | .17** | .05 | |

| Improve on its own | – | −.12*** | .03 | −.18*** | .04 | |||

| Seriousness | – | .13* | .05 | .20*** | .06 | |||

| Interaction terms | ||||||||

| Race × Improve on own | – | .16* | .06 | |||||

| Race × Seriousness | – | −.20 | .11 | |||||

| Constant | 3.44 | .03 | 3.20 | .22 | 3.70 | .14 | 2.73 | .22 |

| R 2 | .010 | .081 | .081 | .061 | ||||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

The number of cases differs slightly for each dependent variable because we excluded respondents with missing data on those variables. Missing values for predictor variables were replaced using conditional mean imputation (Allison 2002)

Effect Modification

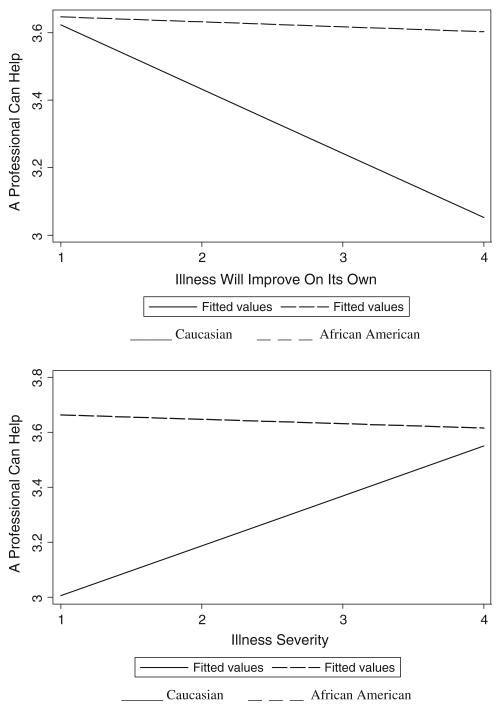

We created cross-product terms to assess whether the relationships between beliefs in the severity and stability of mental illness and perceived effectiveness of mental health professionals were modified by race/ethnicity. Equation 3 indicates that race and beliefs about the course of mental illness interact in their association with perceived efficacy (b = .16, t(650) = 2.56, p < .05). Figure 1 presents these relationships in diagrammatic form and shows that for African Americans, believing a mental illness will improve on its own was unrelated to the beliefin the effectiveness of mental health professionals. Across all levels of belief in the natural course of mental illness, the sentiment that mental health professionals can help remained high for African American respondents. For Caucasians, however, as the belief that mental illness will improve on its own decreased, the belief that a mental health professional can help increased.

Fig. 1.

The modifying effects of beliefs about the natural course and seriousness of mental illness on perceived treatment effectiveness

Equation 4 shows that the cross-product term between race and the belief in the severity of illness trended toward significance (b = −.20, t(646) = −1.79, p < .08). As Caucasian participants’ perceptions of illness severity increases, so does their belief that a mental health professional can help treat the illness. African Americans, on the other hand, endorse the effectiveness of mental health professionals regardless of perceived illness severity.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to shed light on racial differences in mental health help-seeking by examining differences between African Americans and Caucasians in their beliefs about the effectiveness of mental health pro-fessionals, and the severity and natural course of mental illness. Consistent with Schnittker et al. (2005), we found that African Americans were more likely to believe that mental health professionals such as psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers can help individuals suffering from mental illness conditions. Even though studies consistently demonstrate that African Americans underutilize voluntary mental health services (e.g., Wang et al. 2005), our findings strongly suggest that this under-utilization is not driven by skepticism about the effectiveness of treatment. If anything, African American attitudes about treatment are more favorable than those of the Caucasian majority. Consistent with other literature on public attitudes about mental health treatment (Diala et al. 2000; Wetherell et al. 2004), women and younger individuals also held more favorable attitudes regarding the effectiveness of mental health professionals; however, this finding did not explain the more positive attitude among African Americans.

We also examined whether African Americans differ from Caucasians in their views on the natural course of mental illness. We found that a higher percentage of African Americans compared to Caucasians believed that mental illness conditions will improve on their own. If one believes a condition will only remit if treatment is procured and also believes that treatment is effective, it follows that he/she will be more likely to utilize treatment when experiencing symptoms. This describes the situation for Caucasians in the sample and may partly explain why African Americans are less likely to utilize mental health treatment notwithstanding their more positive endorsement of professional care. African Americans may also believe mental illness will remit without professional intervention rendering mental health treatment effective but unnecessary. Furthermore, we found that for African Americans, the belief in the effectiveness of treatment was not at all related to beliefs about the course of illness or the severity of illness. For Caucasians, the belief in the effectiveness of mental health professionals was inversely related to the belief that the condition would improve on its own and positively related to the belief that the condition was serious.

Our analyses revealed an interesting pattern of results. We consistently found strong endorsement of the mental health system among African Americans regardless of other beliefs about the nature of mental illness. These results do not fully explain the discrepancy for African Americans between beliefs in the effectiveness of mental health treatment and actual help seeking. However, our investigation does add to the explanation. For Caucasians, the belief about the effectiveness of professional mental health care is partially contingent upon beliefs that the said illness is serious and unlikely to improve without treatment. On the other hand, African Americans’ strong endorsement of professional services is seemingly not influenced by their notions of mental illness severity and natural course. While one might expect this unwavering endorsement of psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers to translate into increased service use, it is possible that African American beliefs in the likelihood of remittance without professional help undermine their more positive attitudes toward the benefits of seeking care: Why invest the time, energy and money involved in seeking professional treatment when the illness may be transitory?

Research suggests that African Americans are more likely to seek extended family networks and spiritual help when faced with emotional problems (Blank et al. 2002). It is possible that the belief that mental illness will improve without professional mental health intervention is related to the belief that mental illness intervention can improve via other non-professional means (e.g., family elders, pastor). The present study does not have data to test this explicitly, but given the importance of family and religion in African American culture (Boyd-Franklin 2003), future large community studies should assess the extent to which endorsement of non-professional means of mental health care may help explain our findings.

Researchers as well as practitioners working in African American communities must begin to identify factors that undermine these positive expectations about mental health treatment and result in the pattern of African American service underutilization so often identified by large, representative epidemiological studies. Some research suggests that positive, pre-treatment attitudes diminish once contact with mental health professionals is made (Diala et al. 2000), possibly due to a lack of cultural competence among practitioners. This type of therapeutic interaction may give rise to factors such as feelings of cultural mistrust among African American clients, thus eroding initial positive feelings toward treatment. Cultural mistrust has been shown to lead to increased drop-out and decreased client satisfaction among African Americans in treatment (Nickerson et al. 1994; Terrell and Terrell 1984; Watkins and Terrell 1988). More attention should be focused on the dynamics between practitioners and African American clients that might reverse pre-treatment positive attitudes toward therapy.

Potential Limitations

The present study has strengths that add to the literature but is not without limitations. First, two inherent limitations of the vignette experiment should be noted. The vignettes describe specific scenarios, necessarily limiting our ability to generalize to all cases of mental illness. In addition, respondents were asked questions about a hypothetical individual and not themselves. It is possible that answers to questions about oneself might differ from answers about the vignette subject. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to suppose that stated feelings about the effectiveness of mental health professionals would have some bearing on whether respondents feel it would be effective for themselves. Second, we collected no data on participants’ actual mental health service use and therefore cannot say which if any of these beliefs are related to service utilization.

Conclusions and Implications

The findings suggest that, although African Americans are at least as likely as Caucasians to believe mental health professionals can alleviate mental illness, this belief may not have the same implications for service utilization as it does for the Caucasian majority. We found that for African Americans, this belief was not related to other beliefs about the nature of mental illnesses that would likely increase the probability of service utilization. Furthermore, Caucasians actually seek treatment more frequently than African Americans. These facts suggest that endorsement of mental health treatment’s effectiveness may not be as powerful a predictor of service utilization among African Americans as it seems to be for Caucasians. In fact, this belief may have nothing to do with whether an African American will actually go to a mental health professional, and so the belief that a professional can help should not necessarily be equated with more positive attitudes about seeking treatment.

If the goal is to improve service utilization for African Americans, the results of this current research suggest the focus of outreach efforts should be on educating communities about the course of mental illness and its potentially chronic nature. Even though African Americans may believe treatment can help, they might think it is not necessary to rectify problems and instead may believe obtaining help from family members or spiritual leaders (Blank et al. 2002) is just as good if not better than professional care, as well as less expensive. Creating more alliances between spiritual and religious sectors of the African American community and mental health sectors may be a place to begin educating the community about when professional mental health treatment is really necessary. Mental health professionals must capitalize on these pre-existing positive beliefs about treatment’s effectiveness and work to make mental health services more acceptable to African American clients. Crafting messages that reinforce positive expectations is a start, however, more attention needs to be focused on ways in which clienttherapist interactions can maintain these positive expectations in the face of the mistrust and wariness that treatment may engender.

While our data do not allow us to test the impact of these beliefs on service utilization directly, our findings represent a relevant addition to the discussion. Specifically, they suggest that cultural differences in conceptions of mental illness are complex and thus research efforts should spend more time examining beliefs about mental illness. Further research needs to explore how conceptions of mental disease, particularly about the course of illness, may hinder seeking services. Research examining how beliefs about mental illness may delay treatment seeking should be conducted in clinical populations. African Americans may enter services too late because they think the symptoms will get better on their own, and this may lead to poorer psychiatric outcomes. This area of research needs further exploration.

In sum, campaigns designed to increase awareness about the benefits of mental health treatment are designed with the assumption that people will feel a need to go because it is so useful. These efforts may be misguided for African Americans because there is no real relationship between endorsing mental health treatment and believing mental health treatment is necessary. Our results suggest a way in which community psychologists and outreach activists could modify mental health awareness strategies and interventions to be more appropriate and relevant for African Americans.

Contributor Information

Deidre M. Anglin, Department of Epidemiology, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 100 Haven Avenue, Tower 3, Rm 31F, New York, NY 10032, USA

Philip M. Alberti, Department of Epidemiology, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, 722 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

Bruce G. Link, Department of Epidemiology and Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, 722 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

Jo C. Phelan, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, 722 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

References

- Allison PD. Missing data. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin DM, Link BG, Phelan J. Racial differences instigmatizing attitudes about people with mental illness: Extending the literature. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:857–862. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbie E. The practice of social research. 11th ed. Wadsworth; Belmont, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blank MB, Mahmood M, Fox JC, Guterbock T. Alternative mental health services: The Role of the Black church in the South. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1668–1672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: Understanding the African American Experience. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Paradise M, Cochran BN, Shea JM, Srebnik D, et al. Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: A focus on ethnic minority youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:44–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erblaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of American Survey Research Organizations . A Special Report of the CASRO Task Force on Completion Rates. CASRO; New York: 1982. On the definition of response rates. [Google Scholar]

- Diala C, Muntaner C, Walrath C, Nickerson KJ, LaVeist TA, Leaf PJ. Racial differences in attitudes towards professional mental health care and in the use of services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:455–464. doi: 10.1037/h0087736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diala CC, Muntaner C, Walrath C, Nickerson K, LaVeist T, Leaf P. Racial/ethnic differences in attitudes toward seeking professional mental health services. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:805–807. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JH. Bad blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis experiment. The Free Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-IIIR disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The 12-month prevalence and correlates of serious mental illness (SMI) In: Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA, editors. Mental health, United States. Center for Mental Health Services; Rockville, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntaner C. Teaching social inequalities in health: barriers and opportunities. Scandinavia Journal of Public Health. 1999;27:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal AM, Turner SM. Anxiety disorders research with African Americans: Current status. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:400–410. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW. The help-seeking behavior of Black Americans. A summary of findings from the National Survey of Black Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1988;80:1009–1012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson KJ, Helms JE, Terrell F. Cultural mistrust, opinions about mental illness, and Black students’ attitudes toward seeking psychological help from White counselors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1994;41:378–385. [Google Scholar]

- Reiger DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de Facto U.S. mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiological Catchment Area prospective 1-Year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Thomson VL, Bazile A, Akbar M. African American’s perceptions of psychotherapy and psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J, Freese J, Powell B. Nature, nurture, neither, nor: Black-White differences in beliefs about the cause and appropriate treatment of mental illness. Social Forces. 2000;78:1101–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J, Pescosolido BA, Croghan TW. Are African Americans really less willing to use health care? Social Problems. 2005;52:255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Smedly BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. I.o.M. Committee on understanding and eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR. African American service use for mental health problems. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F. Treatment seeking for depression by Black and White Americans. Social Science and Medicine. 1987;24:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Terrell S. Race of counselor, client sex, cultural mistrust level, and premature termination from counseling among Black clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1984;31:371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: Prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins CE, Terrell F. Mistrust level and its effects on counseling expectations in Black client-White counselor relationships: An analogue study. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1988;35:94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell JL, Kaplan RM, Kallenberg G, Dresselhaus TR, Sieber WJ, Lang AJ. Mental health treatment preferences of older and younger primary care patients. International Journal of Psychiatry Medicine. 2004;34:219–233. doi: 10.2190/QA7Y-TX1Y-WM45-KGV7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Cultural mistrust: An important psychological construct for diagnosis and treatment of African Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2001a;32:555–562. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African-Americans: A Review and meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist. 2001b;29:513–531. [Google Scholar]