Abstract

Phytochemical investigation of the MeOH extract of Dioscorea villosa root resulted in the isolation of two new bidesmosidic cholestane steroid glycosides, dioscoreavillosides A and B (1 and 2). In addition, the extract yielded 12 previously known furostane and spirostane steroid glycosides (3-14), along with diosgenin (15). Compounds 3-7, 9, 14, and 15 were isolated for the first time from D. villosa. The structures of the isolated compounds were determined using spectroscopic and chemical methods including 1D and 2D NMR. The antimicrobial action of most of these compounds was tested against five fungal and five bacterial strains.

Keywords: Dioscorea villosa, Dioscoreaceae, Wild yam, Cholestane steroid, Dioscoreavilloside A, Dioscoreavilloside B

1. Introduction

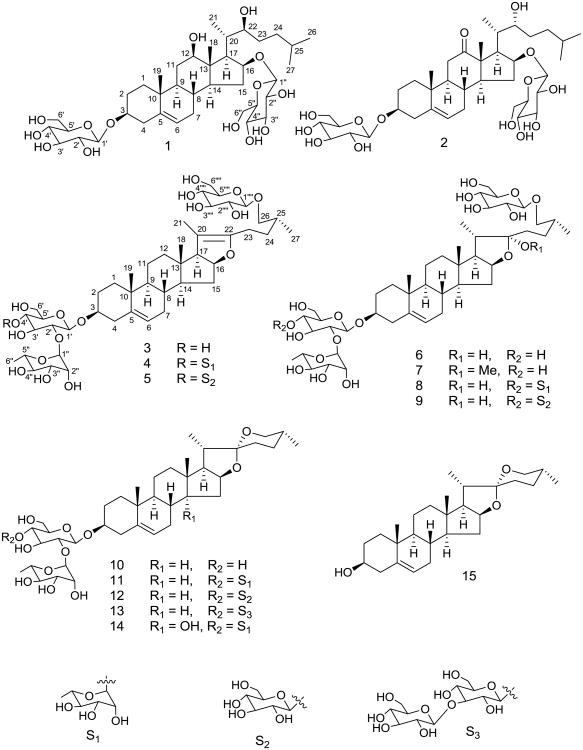

Steroid glycosides are mostly found in Dioscoreaceae, Agavaceae, Liliaceae, and Smilacaceae. Based on the aglycone moiety, steroid saponins can be classified into cholestane, spirostane, furostane, stigmastane, ergostane, and pregnane types. Dioscorea plants are mostly known for their spirostane and furostane steroid glycosides,1 but a few cholestane, ergostane, and pregnane glycosides have also been reported from this plant.2-4 The presence of clerodane diterpenes,5 quinones,6 cyanidins,7 phenolics,8 and nitrogen containing compounds9 in Dioscorea have also been demonstrated. Dioscorea, a genus of over 600 species of flowering plants, is found in tropical and sub-tropical regions. The tuberous rhizomes of many Dioscorea species, known as “Yams”, contain starch and are therefore cultivated for food. Dioscorea villosa L., also known as wild yam, colicroot, rheumatism root or devil's bones, is widely distributed in North America, particularly in the central and southern regions of the United States. It contains diosgenin and diosgenin-based glycosides. Diosgenin, a phytoestrogen, is a spirostane steroid and is used as a source in synthesis of a sex hormone called progesterone. To date, six spirostane and four furostane steroid saponins,1,10,11 along with two flavanol glycosides,11 have been reported from D. villosa. In the present study, a detailed phytochemical investigation of the root of D. villosa was conducted to explore new chemical constituents. Fifteen steroidal compounds (Fig. 1), including two previously undiscovered metabolites, were isolated from its root. The new compounds were characterized as cholestane type steroid glycosides, dioscoreavillosides A and B (1 and 2). As only seven cholestane steroid glycosides have been reported from three Dioscorea species (D. septemloba, D. bulbifera, and D. spongiosa) so far,2,4,12,13 our finding of this class of glycosides from D. villosa has chemotaxonomic importance. Structure elucidation of the isolated compounds was accomplished using spectroscopic and chemical data analyses including 1D and 2D NMR. Previous studies show that among C-27 steroid glycosides, spirostanes possess better antifungal activity, whereas glycosides of furostanes and cholestanes have minor to no activity.14-16 Compounds 1-5 and 7-13 were tested for in vitro antimicrobial activities against five fungal strains (Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus fumigatus) (Table 2) and five bacterial strains (Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Mycobacterium intracellulare).

Fig. 1.

The structures of compounds 1–15.

Table 2. Antifungal activity of compounds 1-5 and 7-13.

| Compounda | C. albicans IC50 (μg/mL) | C. glabrata IC50 (μg/mL) | C. krusei IC50 (μg/mL) | A. fumigatus IC50 (μg/mL) | C. neoformans IC50 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 | NA | 15.99 | NA | NA | NA |

| 11 | 3.97 | 3.26 | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 | 15.24 | 7.35 | NA | NA | 13.17 |

| 13 | NA | 3.09 | NA | NA | 9.70 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 1.18 | 0.35 |

purity of compounds is 92% to 99%

NA = Not active up to the highest concentration of 20 μg/mL.

2. Results and discussion

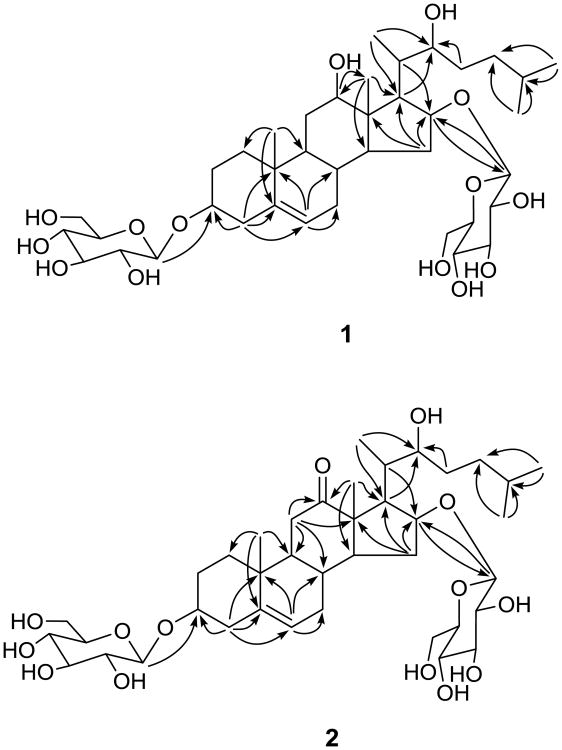

From the MeOH extract of D. villosa root, 15 compounds were isolated using a combination of different types of chromatography over Sephadex LH-20, silica gel, and RP-18 silica gel. The isolated compounds include mostly spirostane, furostane, and cholestane type steroid glycosides. Two new compounds, 1 and 2, are glycosides of cholestane-type steroids. The molecular formula of compound 1 was deduced to be C39H66O14 from a sodiated ion [M + Na]+ at m/z 781.4353 in the HRESI-MS (TOF) (calcd for C39H66O14Na, 781.4350). The 13C NMR spectrum exhibited 39 resonances, of which 27 were attributed to a steroid skeleton and 12 to two sugar units. A DEPT NMR experiment was used to differentiate 39 13C NMR resonances as five methyl, 10 methylene, 21 methine, and three quaternary carbons. The IR spectrum showed absorption due to hydroxy groups at 3376 cm-1. The resonances for two tertiary methyls [δH/δC 1.32/11.0 (CH3-18) and 0.86/19.4 (CH3-19)], three secondary methyls [δH/δC 1.63 (d, J = 7.2 Hz)/13.8 (CH3-21) and 0.85 (d, J = 6.6 Hz)/23.0 (CH3-26, 27)], a double bond [δH/δC 5.25/122.0 (CH-6) and δC 140.9 (C-5)], four oxygenated methines [δH/δC 3.88/78.2 (CH-3), 3.68/78.2 (CH-12), 4.46/84.8 (CH-16), and 4.37/76.1 (CH-22)] along with two β-glucopyranose moieties [δH 4.99 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, H-1′) and 4.82 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-1″) and δC 102.5 (C-1′), 107.2 (C-1″), 75.3, 75.5 (C-2′, C-2″), 78.4, 78.5, 78.9 (C-5′ and C-5″, C-3″, C-3′), 71.7 (C-4′, C-4″), and 62.8, 62.9 (C-6′, C-6″)] were observed in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra (Table 1). The 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data assignment in 1 (Table 1) was based on gHSQC, gHMBC (Fig. 2), and 1H-1H COSY spectroscopic data analyses. The C-5—C-6 double bond and oxygen atoms at C-3, C-12, C-16, and C-22 were supported by the HMBC correlations of H-4 with C-3, C-5, C-6; H-6 with C-8, C-10; H-19 with C-5; H-18 with C-12; H-15, H-17, H-20 with C-16; H-16 with C-13; and H-17, H-21, H-23 with C-22 (Fig. 2). The HMBC correlation of anomeric proton H-1″ (δH 4.82) with C-16 (δC 84.8) revealed the location of sugar unit at C-16. Though the HMBC correlation, observed between anomeric proton H-1′ (δH 4.99) and C-3 (δC 78.2), is not clear due to close chemical schifts of C-3′ and C-5′ inside the sugar unit, but the downfield shift of C-3 from usual chemical shift (71 ppm, if OH is attached) to (78 ppm) strongly supported the sugar unit at C-3. The NMR spectroscopic data of 1 were similar to those of dioseptemloside I,13 except for the fact that the resonances for an additional β-glucopyranose unit were present in 1. The absolute configuration of 1 was found to be similar to that of dioseptemloside I based on their similar NMR data.13 Furthermore, the β-orientation of OH-12 and OH-16 was also supported from the NOESY correlations of H-12 with biogenetically α-oriented H-9, H-14, and H-17 and of H-16 with H-14 and H-17. The S-configuration at C-22 was inferred by comparing its NMR data with those of the S and R stereoisomers.13,17 The sugars were identified as glucose by co-TLC (EtOAc-CHCl3-MeOH-H2O, 6:4:4:1) of standard sugars from Sigma-Aldrich with the sugar mixture obtained via acid hydrolysis of 1. Both glucose units were found to be β based on the characteristic coupling constant values of their anomeric protons (J = 7.7 Hz (H-1′) and J = 7.8 Hz (H-1″)) in the 1H NMR spectrum. The absolute configuration of glucose was determined to be D (see experimental). Accordingly, the structure of dioscoreavilloside A (1) was established as (22S)-3β,16β-di-(O-β-d-glucopyranosyl)-12β,22-dihydroxycholest-5-ene.

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data in C5D5N for compounds 1 and 2.

| Position | 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| δC | δHa (HMQC) | δC | δHa (HMQC) | |

| 1 | 37.5 | 1.76, 0.91 m | 37.2 | 1.45 m, 0.80 td (13.0, 4.3) |

| 2 | 30.2 | 2.03 m, 1.73 | 30.1 | 2.02 m, 1.63 |

| 3 | 78.2 | 3.90 m | 78.0 | 3.88 m |

| 4 | 39.3 | 2.68 dd (13.0, 3.0), 2.40 t (13.0) | 39.1 | 2.66 dd (12.8, 5.4), 2.37 |

| 5 | 140.9 | 140.8 | ||

| 6 | 122.0 | 5.25 br. d (4.7) | 121.9 | 5.19 br. d (4.0) |

| 7 | 31.8 | 1.74, 1.39 | 31.7 | 1.67, 1.26 |

| 8 | 30.6 | 1.28 m | 32.1 | 1.54 m |

| 9 | 49.9 | 0.99 td (12.2, 6.1) | 54.7 | 1.26 td (12.0, 4.8) |

| 10 | 37.0 | 38.0 | ||

| 11 | 31.0 | 1.85, 1.73 | 38.3 | 2.65 t (12.2), 2.16 dd (12.2, 5.4) |

| 12 | 78.2 | 3.68 dt (9.3, 4.5) | 214.6 | |

| 13 | 48.9 | 57.4 | ||

| 14 | 53.9 | 0.79 td (12.2, 6.0) | 57.3 | 1.11 td (12.0, 7.7) |

| 15 | 36.0 | 2.36 dt (13.7, 7.2), 1.92 td (13.7, 4.0) | 37.2 | 2.37, 1.91 td (13.0, 3.6) |

| 16 | 84.8 | 4.46 br. td 7.5, 4.0) | 81.8 | 4.48 br. td (6.5, 3.4) |

| 17 | 63.0 | 1.80 dd (12.9, 11.1) | 49.4 | 2.97 dd (11.0, 7.7) |

| 18 | 11.0 | 1.32 s | 13.5 | 1.26 s |

| 19 | 19.4 | 0.86 s | 19.1 | 0.92 s |

| 20 | 38.1 | 2.81 m | 35.4 | 2.45 m |

| 21 | 13.8 | 1.63 d (7.2) | 13.2 | 1.20 d (6.9) |

| 22 | 76.1 | 4.37 | 73.3 | 4.29 |

| 23 | 35.2 | 1.83, 1.72 | 34.0 | 1.82 |

| 24 | 36.5 | 1.67, 1.47 | 36.9 | 1.91, 1.61 |

| 25 | 28.6 | 1.54 m | 29.0 | 1.57 m |

| 26 | 23.0 | 0.85 d (6.6) | 23.2 | 0.88 d (6.1) |

| 27 | 23.0 | 0.85 d (6.6) | 23.3 | 0.88 d (6.1) |

| 3-Glc | ||||

| 1′ | 102.5 | 4.99 d (7.7) | 102.6 | 4.96 d (7.2) |

| 2′ | 75.3b | 4.01 t like (8.9) | 75.3b | 3.99 t like (9.0) |

| 3′ | 78.9c | 4.18 t (9.0) | 78.7c | 4.13 t (9.0) |

| 4′ | 71.7d | 4.19 t (9.0) | 71.7d | 4.18 t (9.0) |

| 5′ | 78.4 | 3.90 | 78.2e | 3.83 |

| 6′ | 62.8e | 4.36, 4.52 | 62.9 | 4.34, 4.48 |

| 16-Glc | ||||

| 1″ | 107.2 | 4.82 d (7.8) | 107.0 | 4.71 d (7.5) |

| 2″ | 75.5b | 4.01 t like (8.9) | 75.5b | 3.99 t like (9.0.) |

| 3″ | 78.5c | 4.27 t (8.9) | 78.6c | 4.27 t (9.0) |

| 4″ | 71.7d | 4.19 t (8.9) | 71.8d | 4.22 t (9.0) |

| 5″ | 78.4 | 3.88 | 78.4e | 3.90 |

| 6″ | 62.9e | 4.36, 4.52 | 62.9 | 4.34, 4.50 |

multiplicity is not clear for some resonances due to overlapping, chemical shifts are in ppm, J in parenthesis are in hertz.

Interchangeable within the column.

Fig. 2.

Key HMBC correlations of 1 and 2.

The HRESI-MS (TOF) of 2 yielded a sodiated molecular ion [M + Na]+ at m/z 779.4190, which in conjunction with the 13C NMR data, indicated a molecular formula of C39H64O14. The IR spectrum of 2 indicated hydroxyl and carbonyl functions due to absorptions at 3386 and 1699 cm-1, respectively. The 1H and 13C NMR data assignment (Table 1) in the usual manner indicated that compound 2 was also comprised of the cholestane-type steroid with two sugar units. The NMR data of 2 were found to be close to those of 1 except that the resonances for C-12 oxygenated methine (δH/δC 3.68/78.2) and C-22(S) were replaced by those of an oxo group (δC 214.6) and C-22(R), respectively in 2. The oxo function was also supported by the IR spectrum (1699 cm-1) and the mass difference of two units between 1 and 2. The C-12 position of the oxo group was evident from the HMBC correlations of H-11 and H-18 with C-12 (δC 214.6) (Fig. 2). The oxo instead of β-hydroxy group at C-12 resulted in significant downfield carbon chemical shifts for C-9, C-11, C-13, C-14, and C-18 and upfield shift for C-17 (Table 1). Challinor et al.,17 revised the absolute configurations of bethosides B and C at C-22 by preparing 22-R and 22-S analogues. Based on their 13C NMR resonances (δC 73.4 for 22-R and δC 75.5 for 22-S), the configuration at C-22 was assigned as R in 2.17 The sugars and their positions in 2 were found to be similar to those of 1. The 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data assignment in 2 (Table 1) was based on gHSQC, gHMBC (Fig. 2), and 1H-1H COSY spectroscopic data analyses. Thus, the structure of dioscoreavilloside B (2) was elucidated as (22R)-3β,16β-di-(O-β-d-glucopyranosyl)-22-hydroxycholest-5-en-12-one.

The name, huangjiangsu A, for compound 5 has been assigned to two different compounds in literature. It was first reported in D. zingiberensis by Bai and Sun in 2006 without NMR data.18 In 2009, Wang et al., had reported it as (25R)-26-O-{β-d-glucopyranosyl}-furost-5,20(22)-dienyl-3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-[α-l-rhamnopynosyl-(1→2)]-β-d-galactopyranoside with a galactose unit instead of glucose.19 In the current study, the structure of 5 was elucidated with glucose unit as reported by Bai and Sun18 instead of galactose, despite the similarity of its NMR spectroscopic data with those reported by Wang et al.19 The sugars were identified as glucose and rhamnose by co-TLC (EtOAc-CHCl3-MeOH-H2O, 6:4:4:1) of standard sugars from Sigma-Aldrich with the sugar mixture obtained via acid hydrolysis of 5. The absolute configurations of glucose and rhamnose were determined to be D and L, respectively (see experimental).

25(R)-Dracaenoside G (14) was isolated and identified for the first as a single isomer with a 25R configuration at C-25 similar to that found in compounds 10-13. Previously, this compound was reported in mixture form as 25(R,S)-dracaenoside G.20

Other known compounds were identified as 26-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-3β,26-diol-25(R)-furost-5,20(22)-dien-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl(1→2)-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (3), 21 pseudoprotodioscin (4),22 protobioside (6),23,24 methyl protobioside (7),24,25 protodioscin (8),26 protodeltonin (9),27 progenin III (10),10 dioscin (11),10 deltonin (12),10 zingiberensis saponin I (13),10 and diosgenin (15).

In accordance to the previous report, spirostane glycosides 11 and 12 showed antifungal activity against C. albicans and C. glabrata (Table 2).14 Antifungal activities of 10 and 13 against C. glabrata and 12 and 13 against C. neoformans were also observed. The antifungal activity results of three types of C-27 steroid glycosides (Table 2), in compliance to the previous reports,14-16 showed that spirostane glycosides have better activity than furostane and cholestane types. It is also concluded that the antifungal activity in a respective class of steroid glycosides depends on the types and sequence of the sugars. None of the compounds showed antibacterial activity up to the test concentration of 20 μg/mL.

3. Experimental

3.1. General methods

Specific rotations were measured at ambient temperature using a Rudolph Research Analytical Autopol IV automatic polarimeter. IR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrophotometer. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Unity Inova 600 MHz NMR spectrometer, whereas HRESI-MS (TOF) data were obtained on an Agilent Series 1100 SL mass spectrometer. TLC was carried out on aluminum-backed plates pre-coated with silica gel F254 (20 × 20 cm, 200 μm, 60 Å, Merck). Visualization was accomplished by spraying with 5% vanillin (Sigma) solution in conc. H2SO4-95% EtOH (5:95) followed by heating. Chromatography was performed using silica gel (40 μm for flash chromatography, 60 Å, J. T. Baker), reversed-phase RP-C18 silica (Polarbond, JT Baker), and Sephadex LH-20 (Sigma). HPLC was carried out on a Waters Alliance 2695, equipped with a 996 photodiode array detector (Waters Corp., Milford, MA), with Waters Empower-2 software. A Luna C-18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size, Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA) was protected with a 2 cm LC-18 guard column (Phenomenex Inc.). The solvents (Fisher brand) used for HPLC and other chromatographic procedures were of HPLC and certified grades, respectively. All organisms were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Drug controls [Ciprofloxacin (99.3%) for bacteria and Amphotericin B (92%) for fungi] were obtained from ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH.

3.2. Plant material

Root powder of D. villosa was purchased from Starwest Botanicals, USA in April, 2011. Authenticity of the plant material was confirmed by comparison of the TLC of its MeOH extract with that of a limited quantity of an authentic plant material grown at the Medicinal Botanical Garden (MBG) at the University of Mississippi. The plant material obtained from the MBG was identified by Dr. Aruna Weerasooriya of the University of Mississippi. A voucher specimen (No. 9800) and a sample specimen of the purchased material (No. 9412) were deposited at the National Center for Natural Products Research, University of Mississippi.

3.3. Extraction and isolation

Root powder (0.9 kg) was extracted with MeOH (3.0 L × 4 × 24 h) at room temperature. Following the removal of the solvent, a gummy residue (75 g) was obtained. An aliquot (55 g) was subjected to size exclusion chromatography using Sephadex LH-20 (17 × 10 cm) and eluted with MeOH to furnish 2 aliquots, A (7.0 L, 45.2 g) and B (5.0 L, 9.4 g). Part A (30 g) was separated by normal phase column chromatography (NPCC) using silica gel (30 × 10 cm) into 12 fractions (A1-A12) with lower layer of CHCl3-MeOH-H2O (13:7:2) [A1 (0.5 L, 782 mg), A2 (1.0 L, 730 mg), A3 (0.5 L, 304 mg), A4 (0.5 L, 767 mg), A5 (0.5 L, 490 mg), A6 (0.5 L, 1.8 g), A7 (1.0 L, 657 mg), A8 (1.0 L, 2.8 g), A9 (1.0 L, 1.9 g), A10 (1.5 L, 4.4 g), A11 (1.5 L, 4.5 g), and A12 (1.5 L, 5.9 g)]. Fractions A3 and A4 were individually subjected to NPCC [silica gel (87 × 1.3 cm), EtOAc-CHCl3-MeOH-H2O (10:6:4:1), 1.0 L] to yield compounds 10 (375 mg) and 11 (126 mg). Fraction A5 yielded seven subfractions (A5a-A5g) by NPCC [silica gel (87 × 1.3 cm), EtOAc-CHCl3-MeOH-H2O (10:6:4:1), 1.5 L]. Compounds 1 (34 mg) and 2 (38 mg) were purified from subfraction A5g (112 mg) by reversed phase chromatography (RPC) [RP-18 silica gel (45 × 1.3 cm), acetone-H2O (2:3), 0.5 L], and 14 (3 mg) was obtained from subfraction A5e (26 mg) by RPC [RP-18 silica gel (45 × 1.3 cm), MeOH-H2O (9:1), 0.3 L]. Compounds 12 (785 mg) and 13 (90 mg) were obtained from fractions A6 and A8, respectively, as MeOH insoluble materials. Compounds 3 (32 mg) and 7 (325 mg) were purified from the MeOH soluble part of fraction A8 by NPCC [silica gel (87 × 2.5 cm), CHCl3-MeOH-H2O (32:8:1), 4.5 L] and RPC [RP-18 silica gel (37 × 2.5 cm), acetone-H2O (1:1), 0.5 L]. Fraction A9 was resolved by NPCC [silica gel (37 × 2.5 cm), lower layer of CHCl3-MeOH-H2O (13:7:2), 2.7 L] into three subfractions (A9a-A9c). Compound 6 (22 mg) was obtained from subfraction A9a (113 mg) by RPC [RP-18 silica gel (37 × 1.3 cm), acetone-H2O (1:1), 0.5 L]. Compounds 4 (45 mg) and 8 (212 mg) were purified from subfraction A9c (665 mg) by RPC [RP-18 silica gel (45 × 2.5 cm), acetone-H2O (2:3), 0.7 L]. Compounds 5 (646 mg) and 9 (1.3 g) were purified from fraction A11 by RPC [RP-18 silica gel (50 × 3.7 cm), acetone-H2O (2:3), 2.5 L]. Part B (5 g) was fractionated into seven fractions (B1-B7) by CC over silica gel (45 × 7.5 cm) and eluted with CHCl3-MeOH gradients [B1 (1:0, 2.0 L, 117 mg), B2 (1:0, 2.0 L, 22 mg), B3 (1:0, 2.0 L, 48 mg), B4 (19:1, 4.0 L, 1.1 g), B5 (9:1), 3.0 L, 618 mg), B6 (4:1), 4.0 L, 594 mg), and B7 (0:1), 2.0 L, 1.7 g)]. Fraction B4 was subjected to RPC [RP-18 silica gel (50 × 1.7 cm), MeOH-H2O (9:1, 0.5 L), (1:0, 1.0 L) and acetone (0.5 L)] to give 11 subfractions (B4a-B4k). Compound 15 (11 mg) was found as a pure substance in subfraction B4e.

3.4. Identification of compounds

3.4.1. Dioscoreavilloside A (1)

Colorless solid; [α]22D – 34.0 (c 0.1, MeOH); IR vmax (NaCl): 3376 (OH), 2943, 1649, 1367, 1075, 1024 cm-1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, C5D5N) and 13C NMR (150 MHz, C5D5N) spectroscopic data: see Table 1; HRESI-MS: m/z 781.4353 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C39H66O14Na, 781.4350).

3.4.2. Dioscoreavilloside B (2)

Colorless solid; [α]22D – 14.0 (c 0.1, MeOH); IR vmax (NaCl): 3386 (OH), 2939, 1699 (C=O), 1456, 1370, 1073, 1029 cm-1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, C5D5N) and 13C NMR (150 MHz, C5D5N) spectroscopic data: see Table 1; HRESI-MS: m/z 779.4190 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C39H64O14Na, 779.4194).

3.4.3. Huangjiangsu A (5)

13C NMR (C5D5N, 150 MHz) spectroscopic data: δC (ppm) 37.8 (C-1), 30.4 (C-2), 78.7 (C-3), 39.2 (C-4), 141.0 (C-5), 122.1 (C-6), 32.7 (C-7), 31.7 (C-8), 50.6 (C-9), 37.4 (C-10), 21.5 (C-11), 39.9 (C-12), 43.7 (C-13), 55.2 (C-14), 34.7 (C-15), 84.8 (C-16), 64.8 (C-17), 14.4 (C-18), 19.7 (C-19), 103.9 (C-20), 12.1 (C-21), 152.6 (C-22), 24.0 (C-23), 31.7 (C-24), 33.8 (C-25), 75.2 (C-26), 17.6 (C-27), 100.2 (C-1′), 78.5 (C-2′), 77.6 (C-3′), 82.2 (C-4′), 76.4 (C-5′), 62.1 (C-6′), 102.1 (C-1″), 72.7 (C-2″), 73.0 (C-3″), 74.3 (C-4″), 69.8 (C-5″), 18.9 (C-6″), 105.4 (C-1‴), 75.2 (C-2‴), 78.0 (C-3‴), 71.5 (C-4‴), 78.4 (C-5‴), 62.3 (C-6‴), 105.1 (C-1⁗), 75.5 (C-2⁗), 78.8 (C-3⁗), 72.0 (C-4⁗), 78.9 (C-5⁗), 63.1(C-6⁗); 1H NMR (C5D5N, 600 MHz) spectroscopic data: δH (ppm) 1.73, 0.98 (H-1a/b), 2.11 (H-2a/b), 3.86 (m, H-3), 2.75, 2.71 (H-4a/b), 5.31 (br. s H-6), 1.95, 1.40 (H-7a/b), 1.48 (H-8), 0.89 (H-9), 1.48 (H-11a/b), 1.74, 1.16 (H-12a/b), 0.90 (H-14), 2.11, 1.50 (H-15a/b), 4.80 (m, H-16), 2.45 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, H-17), 0.72 (s, H-18), 1.02 (s, H-19), 1.64 (s, H-21), 2.22 (H-23a/b), 1.80 (H-24a/b), 1.96 (H-25), 4.03, 3.61 (H-26a/b), 1.01 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, H-27), 4.95 (d, J = 72 Hz, H-1′), 4.44-3.85 (H-2′/3′/3‴/5‴/3⁗/5⁗), 4.23 (H-4′), 3.86 (H-5′), 4.58-4.29 (H-6a′/6b′/6a‴/6b‴/6a⁗/6b⁗), 6.24 (s, H-1″), 4.75 (s, H-2″), 4.58 (H-3″), 4.35 (H-4″), 4.94 (H-5″), 1.76 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-6″), 5.13 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, H-1‴), 4.06, 4.02 (H-2‴/2⁗), 4.26 (H-4‴/4⁗), 4.84 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, H-1⁗).

3.5. Sugar analyses

Compound 1 (3 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of 2 N HCl in dioxane-H2O (1:1) and heated at 95 °C for 3 h. The mixture was diluted with H2O (1 mL) on cooling, then neutralized with NH4OH and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 2 mL). The residue obtained after drying the aqueous layer was dissolved in pyridine (1 mL) and 0.1 M cysteine methyl ester hydrochloride in pyridine (1 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at 60 °C for 1h. An equal volume of phenyl isothiocyanate in pyridine (10 mg/mL) was added and heated at 60 °C for 1h. The mixture was filtered and analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC. Acetonitrile (ACN) with 0.1% HOAc (A) and H2O with 0.1% HOAc (B) were used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with the following gradient: 10 % A for 20 min and 55 % A for 25 min. The chromatographic peaks were detected at 250 nm. The process was repeated for compounds 2 and 5. The standard sugar (Sigma-Aldrich) derivatives were prepared identically and analyzed by HPLC under similar conditions. A pair of isomers (major & minor) was detected in each case. d-Glucose in compounds 1 and 2 and d-glucose and l-rhamnose in compound 5 were identified by comparing the retention times of their derivatives with those of authentic sugar samples [d-glucose: 12.6 min (minor)/15.3 min (major), l-glucose: 13.1 min (minor)/15.2 min (major), and l-rhamnose: 14.4 min (minor)/17.4 min (major)].

3.6. Assays for in vitro antimicrobial activity

Assays were performed as described earlier.14

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

► Phytochemical investigation of the MeOH extract of Dioscorea villosa root. ► Fifteen compounds including two new bidesmosidic cholestane steroid glycosides. ► Structures elucidation by spectroscopic and chemical methods. ► Antimicrobial action of the isolated compounds.

Acknowledgments

This research work was supported by an NIH grant entitled “Botanical Identification, Characterization, Quality Assurance and Quality Control” (NIH Prime award number 1P50AT006268-01) and The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Specific Cooperative Research Agreement Number U01 FD004246-01. This work was also partially supported by the NIH, NIAID, Division of AIDS, Grant No. AI 27094 and the USDA Agricultural Research Service Specific Cooperative Agreement No. 58-6408-1-603. The authors are thankful to Dr. Melissa R. Jacob for antimicrobial screening, Dr. Bharathi Avula for mass analysis and Dr. Aruna Weerasooriya for providing an authentic plant sample.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hu CC, Lin JT, Liu SC, Yang DJ. J Food Drug Anal. 2007;15:310–315. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu XT, Wang ZZ, Xiao W, Zhao HW, Hu J, Yu B. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:1411–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen P, Wang SL, Liu XK, Yang CR, Cai B, Yao XS. J Asian Nat Prod, Res. 2002;4:211–215. doi: 10.1080/10286020290024013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin J, Kouda K, Tezuka Y, Tran QL, Miyahara T, Chen Y, Kadota S. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:646–650. doi: 10.1021/np0205957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teponno RB, Tapondjou AL, Abou-Mansour E, Stoeckli-Evans H, Tane P, Barboni L. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:2374–2379. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itharat A, Plubrukarn A, Kongsaeree P, Bui T, Keawpradub N, Houghton PJ. Org Lett. 2003;5:2879–2882. doi: 10.1021/ol034926y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoyama Y, Nishioka I, Herath W, Uemoto S, Fujieda K, Okubo H. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:2999–3001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SL, Liu XK. Chin Chem Lett. 2005;16:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwu MM, Okunji CO, Akah P, Tempesta MS, Corley D. Planta Med. 1990;56:119–120. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes PY, Lambert LK, Lehmann R, Penman K, Kitching W, De VJJ. Magn Reson Chem. 2007;45:1001–1005. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sautour M, Miyamoto T, Lacaille-Dubois MA. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2006;34:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, Chou GX, Wu T, Guo YL, Wang SC, Wang CH, Wang ZT. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1964–1968. doi: 10.1021/np900255h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu XT, Wang ZZ, Xiao W, Zhao HW, Yu B. Planta Med. 2010;76:291–294. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1186063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang CR, Zhang Y, Jacob MR, Khan SI, Zhang YJ, Li XC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1710–1714. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1710-1714.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang CR, Li XC. In: Advances in Experimental and Medicinal Biology. Waller GR, Yamasaki K, editors. Vol. 404. Plenum Publishing Co.; New York: 1996. pp. 225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cammarata A, Upadhyay SK, Jursic BS, Neumann DM. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:7379–7386. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Challinor VL, Hayes PY, Bernhardt PV, Kitching W, Lehmann RP, De VJJ. J Org Chem. 2011;76:7275–7280. doi: 10.1021/jo2012797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai X, Sun W. Chin J Pharm Anal. 2006;26:1785–1787. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Lai D, Zhang Y, Kang A, Cao Y, Sun W. J Nat Prod (Gorakhpur, India) 2009;2:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng QA, Zhang YJ, Li HZ, Yang CR. Steroids. 2004;69:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong M, Wu L, Chen Q, Wang B. Yaoxue Xuebao. 2001;36:42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshikawa M, Xu F, Morikawa T, Pongpiriyadacha Y, Nakamura S, Asao Y, Kumahara A, Matsuda H. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:308–316. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Hu C, Pang Z, Xu D. Zhongcaoyao. 2009;40:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen P, Wang SL, Liu XK, Yang CR, Cai B, Yao XS. Chin Chem Lett. 2002;13:851–854. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva BP, Bernardo RR, Parente JP. Fitoterapia. 1998;69:528–532. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao Y, Poobrasert O, Kennelly EJ, Chin CK, Ho CT, Huang MT, Garrison SA, Cordell GA. Planta Med. 1997;63:258–262. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munafo JP, Jr, Ramanathan A, Jimenez LS, Gianfagna TJ. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:8806–8813. doi: 10.1021/jf101410d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.