Abstract

Background

Le Fort-based, maxillofacial allotransplantation is a reconstructive alternative gaining clinical acceptance. However, the vast majority of single-jaw transplant recipients demonstrate less-than-ideal skeletal and dental relationships with suboptimal aesthetic harmony. The purpose of this study was to investigate reproducible cephalometric landmarks in a large animal model, where refinement of computer-assisted planning, intra-operative navigational guidance, translational bone osteotomies, and comparative surgical techniques could be performed.

Methods

Cephalometric landmarks that could be translated into the human craniomaxillofacial skeleton, and would remain reliable following maxillofacial osteotomies with mid-facial alloflap inset, were sought on six miniature swine. Le Fort I-and Le Fort III-based alloflaps were harvested in swine with osteotomies, and all alloflaps were either auto-replanted or transplanted. Cephalometric analyses were performed on lateral cephalograms pre- and post-operatively. Critical cephalometric data sets were identified with the assistance of surgical planning and virtual prediction software, and evaluated for reliability and translational predictability.

Results

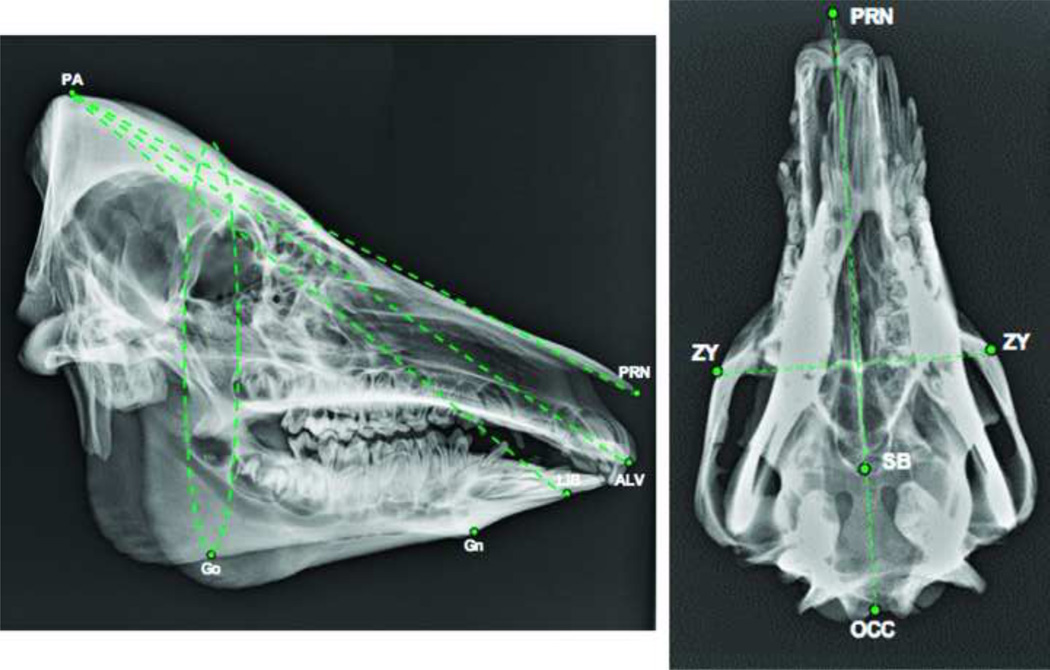

Several pertinent landmarks and human analogues were identified including pronasale (PRN), zygion (Zy), parietale (PA), gonion (GO), gnathion (GN), lower incisior base (LIB), and alveolare (ALV). PA-PRN-ALV and PA-PRN-LIB were found to be reliable correlates of SNA and SNB measurements in humans, respectively.

Conclusions

There is a set of reliable cephalometric landmarks and measurement angles pertinent for utilization within a translational large animal model. These craniomaxillofacial landmarks will allow us to develop novel navigational software technology, improve our cutting guide designs, and explore new avenues for investigation and collaboration.

Level of Evidence

N/A (Large Animal Study)

Keywords: Maxillofacial Transplant, Swine Facial Transplant, Cephalometrics, Cephalomtetric landmark, Craniofacial, Craniomaxillofacial surgery, Swine study, Face transplant, Allotransplantation, Computer assisted, Computer enhanced surgery, Cutting guides

INTRODUCTION

Le Fort-based, single-jaw maxillofacial allotransplantation is a novel reconstructive alternative, with only nine operations being performed to date.1–3 Facial skeletal allotransplantation allows for unprecedented restoration of skeletal form, as well as sensory, functional, and soft tissue mid-face reconstruction.4 Despite these advances, many transplant recipients have been left with suboptimal dentofacial deformities such as skeletal malalignment, malocclusion, retrognathia, anterior open bite, and aesthetic disharmony.5 Until recently, the concept of “hybrid occlusion” had not been proposed; the term “hybrid occlusion” (first described by our team) represents the post-transplant relation of two human jaws of varying anthropometrics (i.e. a native jaw and an allograft jaw). This terminology was introduced following a cadaver study investigating Le Fort based, craniomaxillofacial (CMF) allotransplantation.1 Findings have suggested that pre-operative planning using cephalometic analysis of donor and recipient may lead to improved post-operative skeletal relation, facial harmony, and optimized occlusion.1,2,4,5

The use of swine as a reliable model for craniofacial surgery has been well described.6–9 Given the previously described challenges, a suitable large-animal model upon which peri-operative techniques can be practiced, reproduced and refined, is an essential investigative tool. Furthermore, with recent advances in computer-assisted planning for skeletal surgery, such a model would allow investigators the rare opportunity to utilize computer-enhanced technology and design custom surgical guides.10–12

While small animal models and human cadaver studies have added significantly to the literature on craniomaxillofacial allotransplantation, they are not without their limitations. Small animal models, such as those described by Siemionow in rats, are highly limited in their ability to study translational osteotomies, develop new techniques and/or technologies due to their facial skeletal size and anatomical limitations.13 Similarly, human cadaver studies, while the most analogous model for clinical practice, and used by several groups to successfully plan operations and optimize skeletal fixation, are limited by the lack of a suitable live-model surgery analogue, biomechanical obstacles associated with one’s masticatory muscles due to the cadaver’s rigor mortis, and limited jaw mobility.1–2, 5,15–16 Cadavers also have limited potential for assessment of the safety and clinical outcomes of new innovations post-transplant and are therefore inadequate for our study’s aims.1

The purpose of this study was to develop a swine orthotopic face transplant model. Our group hypothesized that it would be possible to identify and establish a set of reproducible landmarks for the pre-clinical investigation of skeletal harmony, and hybrid occlusion. Our specific aims were to identify translational cephalometric landmarks in swine which were analogous to human landmarks to allow for data collection and validation. A secondary aim was to develop a novel computer-assisted planning and execution (CAPE) system for adaption to both large animal and human pre-operative surgical planning and intra-operative surgical navigation.11 To our knowledge, this is the first study to implement computer-assisted cephalometric analysis in swine.

METHODS

We sought to identify skeletal landmarks that could be translated to the human craniofacial skeleton and vice versa. Three main sets of landmarks were proposed: 1) an angular set to the cranium, 2) a linear set for the maxillomandibular relationship, and 3) a linear set for the occlusal plane sagittal maxillomandibular relationship. Craniofacial landmarks, which could be readily translated to the human facial skeleton, would remain reliable following maxillofacial osteotomies and mid-facial alloflap inset, and were within or outside the lines of planned osteotomies, were to be identified on six miniature swine skulls of varying age, sex and size (Figs. 1–4). Anthropometrics of swine and human cadaver skulls were initially compared based on prior work by our group, and homologous craniofacial landmarks were chosen as candidates.1,6,7 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Preliminary results validating cephalometric (hard tissue) data for translational studies in swine. [PA-parietale, PRN-pronasale, ALV-alveolare, LIB-lower incisor base, GN-gonion, GO-gonion, ZY-zygion, SB-skull base, OCC-occipitale].

Figure 4.

Pre-operative cephalometic analysis of native recipient swine mandible and maxilla. Outline tracings of first molar and central incisor are shown.

Table 1.

Cephalometric Landmarks used for pre and post-operative analysis in the Swine skull and their analogs in the human skull.

| Swine Cephalometric Landmark |

Definition in Swine | Human Analog |

|---|---|---|

| GO | Gonion = a point mid-way between points defining angles of the mandible | Gonion |

| GN | Gnathion = most convex point located at the symphysis of the mandible | Menton |

| ALV | ALV (Alveolare) = Mid-line of alveolar process of the upper jaw, at incisor – alveolar junction | A-point |

| LIB | Lower Incisor Base = midline of anterior border of alveolar process of mandible at the incisor-alveolar junction | B-point |

| PA | Parietale = Most superior aspect of skull in the midline, (formed by nuchal crest of occipital bone and parietal bone) | Sella (S) |

| PRN | PRN (Pronasale) = Bony landmark representing anterior limit of nasal bone | Rhinion |

| ZY | Zygion = Most lateral point of malar bone | Zygion |

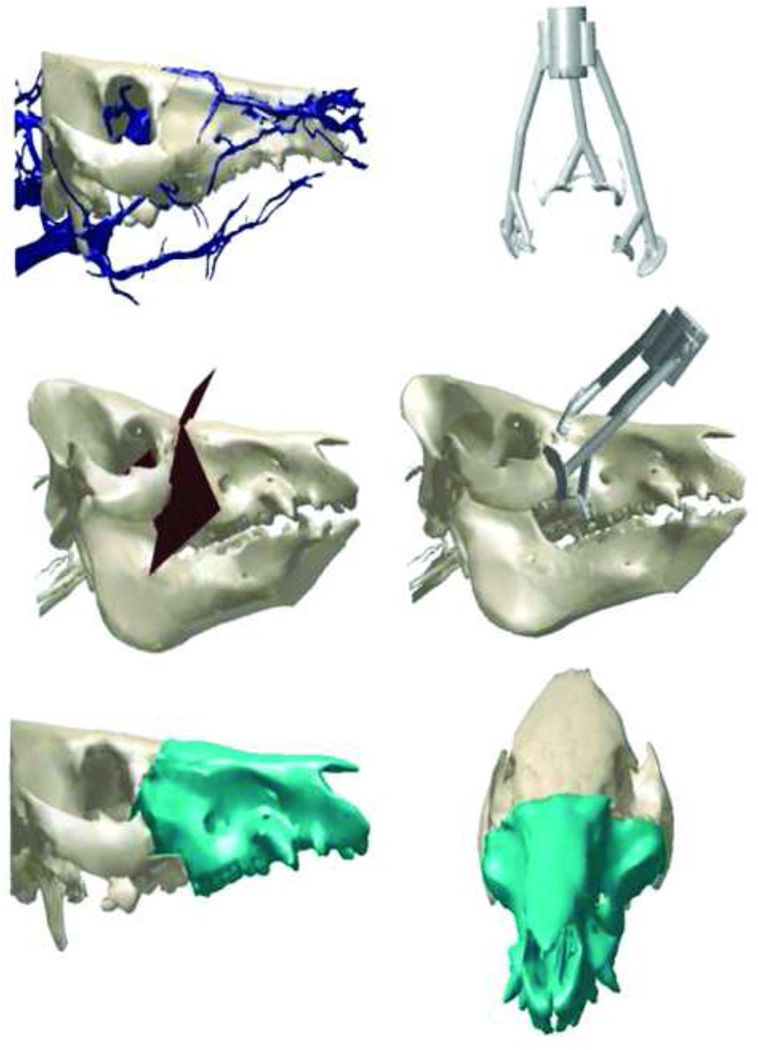

Following landmark identification, cephalometric analyses were performed on native pig craniums and mandibles using the Dolphin Imaging Plus™ program (Figs. 4,5). Two swine subsequently underwent Le Fort III-based mid-facial alloflap harvest followed by autotransplantation and rigid fixation. Anterior-posterior and lateral cephalometric analyses were performed on all autotransplanted swine post-operatively. In parallel, we concentrated on confirming adequate perfusion to our alloflap design for the purpose of translational study with near-infrared laser angiography (Fig. 6,7). Once vascularity was confirmed, our team moved forward with allotransplantation in the setting of custom surgical osteotomy guides and employed virtual planning to offset the challenge of large size mismatch discrepancies. To achieve excellent orthognathic profiles, dental alignment, and corresponding aesthetic harmony in both auto and allotransplants, we investigated numerous designs for cutting guide fabrication and modified them with each surgery performed (Figs. 8,9). This was done in collaboration with the 3D Medical Applications Center at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, MD).

Figure 5.

Intraoperative view and near-infrared laser imaging assessment of swine following Le Fort-based osteotomies with preservation of right vascular pedicle and viable snout perfusion. The swine’s left vascular pedicle has been divided as demonstrated in both images.

Figure 6.

Near-infrared laser angiography demonstrates acceptable blood perfusion to the tip of the snout (red arrow) following a Le fort-based, maxillofacial flap dissection. The alloflap is completely free from all surrounding facial skeletal structures with perfusion based solely on bilateral pedicles, which is directly translational to humans.

Figure 7.

Planned markings include incisions (solid lines) and maxillary osteotomy (dotted) for Le Fort I facial alloflap harvest.

Figure 8.

Intraoperative facial alloflap harvest. Real-time surgical navigation hardware with tracking spheres and cutting guide attached to bony component of flap.

Figure 9.

Photograph demonstrates navigational hardware assembly designed by the Applied Physics Laboratory for three-dimensional registration of the cranium.

Our team was able to design navigational hardware and software based on our collaborator’s previously-published experience with navigational technology in orthopedic surgery.11,12 Development of our large-animal model provided a pre-clinical platform for the development of a computer-assisted planning and execution (CAPE) system, applicable to all types of complex craniomaxillofacial surgery including facial allotransplantation. Our goal was to combine pre-operative planning and intraoperative surgical navigation into one system that enabled a high degree of precision and reproducibility in craniofacial surgery (Figs. 10,11). Our collaboration with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics laboratory was critical for this portion of our project.

Figure 10.

Photograph demonstrates navigational instrument used for three-dimensional registration of the maxillofacial alloflap.

Figure 11.

Virtual planning of the transplants were performed via three-dimensional CT scan reconstruction files of donor and recipient. Virtual osteotomies were then performed within the software (MIMICS: Materialise, Ann Arbor, MI) to optimize the donor/recipient match in collaboration with the 3D Medical Applications Center at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

After refining the autotransplantation technique, we sought to determine whether the post-operative maxillo-mandibular relationship could be enhanced with the aid of computer assisted pre-operative planning and live-intraoperative surgical navigation in coordination with custom surgical guides. Donors and recipients were obtained and purposely chosen based on a large size mismatch skeletal discrepancy in an effort to challenge the aforementioned innovations. Both size mismatched transplant procedures consisted of transplanting a larger maxillofacial alloflap onto a smaller recipient. Two live orthotopic Le Fort-I based allotransplants were performed with the use of a computer-assisted planning and execution (CAPE) system. The virtual planning for these surgeries was performed via three-dimensional CT scan reconstruction files of the recipient and donor. Virtual osteotomies were then performed within the software (MIMICS: Materialise, Ann Arbor, MI) to optimize the donor/recipient match (Fig. 12). Custom cutting guide templates were designed and navigational registration elements were added (Freeform Plus, 3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC). The surgical guides were manufactured via stereolithography or fused deposition modeling additive manufacturing technology (AMT), as previously described by our team (Fig. 9).11 Cephalometric analysis was performed post-operatively using Dolphin (Dolphin 3D; Dolphin Imaging, Chatsworth, Calif) to evaluate facial skeletal maxillary-mandibular relationship, as well as to identify whether optimal “hybrid occlusion” was obtained through the use of this preliminary technology.

Figure 12.

Post-operative result: Lateral cephalograms showing translation of surgical techniques of Le Fort-based facial allotransplantation from swine to human.

RESULTS

Several cephalometric landmarks were identified and found to be conserved in translational fashion from swine to humans and vice versa. Following analysis, we identified various pertinent points including pronasale (PRN), zygion (Zy), parietale (PA), gonion (GO), gnathion (GN), lower incisor base (LIB), and alveolare (ALV). Each of these landmarks remained consistent throughout the study (Table 1).

These landmarks were then incorporated into a comprehensive system of cephalometric data sets, and the most reproducibly identifiable points were used to compare all native and post-operative swine skulls (Table 2,3). Refinement of our perioperative procedures during this time included tracheostomy placement with a customordered elongated appliance and wire-reinforced tubing, transitioning over from an esophagostomy to percutaneous gastrosotomy (PEG) tube, and adjusting from cervical to femoral placement of a Hickman tunneled catheter.

Table 2.

Cephalometric Measurements (millimeters), † Degrees

| SWINE | Occ- PRN |

ZY- ZY |

PA- PRN |

GO- GN |

GO- LIB |

PA- ALV |

PA-ALV- LIB† |

Overbite | Overjet | Lib- ALV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Native skull | 118.4 | 85.6 | 191.6 | 110.6 | 4.8 | 198.6 | 4.8 | 3 | −10 | 9.5 |

| Small Native skull | 103.2 | 84.8 | 182.3 | 82.5 | 6.33 | 190.5 | 6.33 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 20.1 |

| 1st LF III Replant (Pre-op) | 142.6 | 95.7 | 253.5 | 150.8 | 4.85 | 260.5 | 4.85 | 3 | 5.1 | 24.7 |

| 1st LF III Replant (Post-op) | 143.2 | 96.2 | 259.2 | 150.8 | 4.85 | 265.3 | 4.75 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 25.1 |

| 2nd LF III Replant (Post-op) | 141.6 | 96.9 | 184.8 | 75.8 | 112.2 | 197.1 | 4.4 | −8 | −12 | 1 |

| 2nd LF III Replant (Post-op) | 142.9 | 95 | 198.2 | 75.8 | 112.2 | 207.6 | 4.8 | 2 | 5 | 18 |

Figure 3.

Pre-operative cephalometic analysis of native donor swine mandible and maxilla depicting PA-PRN and the occlusal plane. Outline tracings of first molar and central incisor are shown.

Both Le Fort III-based auto-replants and Le Fort I-based allotransplants were successful in achieving acceptable post-operative skeletal relationships when compared to reference values of native pig skulls. Previous Le Fort-based human cadaveric transplant studies used a system of cephalometric measurements to determine facial skeletal relation (Fig. 13).1–2 The measurements in those studies evaluated sellion-nasion-A point (SNA) angle, sellion-nasion-B point (SNB) angle, and lower-anterior-facial-height to total-anterior-facial-height (LAFH/ TAFH) ratio. By using the swine correlates to human cephalometric landmarks in Table 1 as a reference, we chose to use the angle of Parietale – Pronasale – Alveolare (PA-PRN-ALV) as a corollary to the SNA measurement in humans. We chose to measure the angle of Parietale – Pronasale – Lower Incisor Base (PA-PRN-LIB) as a corollary to the SNB measurement in humans and ALV-PRN-LIB as a corollary to the ANB angle in human cephalometric Steiner analysis.

Figure 13.

Post-operative result: 3-dimensional CT Reconstructions showing translation of surgical techniques of Le Fort-based facial allotransplantation from swine to human.

This study did not evaluate facial height in the swine skull as had been done in prior human cadaver studies because of morphologic differences between swine and human skulls (swine having more prominent premaxillae than humans) (Figs. 14,15).10 We chose instead to evaluate Occlusal Angle to PA-PRN (Fig. 4) as these values in native skulls tended to fall within a close range of each other (Table 3).

Figure 14.

Post-operative results: Showing translation of surgical techniques of Le Fortbased facial allotransplantation from swine to human.

Figure 15.

Post-operative 3-dimensional CT Reconstructions: Le Fort III-based facial auto-replant (A) and Le Fort I-based facial allotransplant in large size-mismatched swine depicting optimal skeletal relation and dental alignment (B).

Table 3.

Cephalometric Measurements, †Degrees.

| SWINE | PA-PRN-ALV† | PA-PRN-LIB† | ALV-PRN- LIB† |

Occlusal Angle to PA-PRN† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Native Skull | 104.6 | 94.7 | 9.9 | −16.1 |

| Large Native Skull | 97.0 | 93.9 | 3.1 | −16.6 |

| Auto Transplant 1 (pre-op) | 106.7 | 87.9 | 18.9 | −9.3 |

| Auto Transplant 1(post-op) | 108.6 | 87.8 | 20.8 | −11.7 |

| Auto Transplant 2(pre-op) | 104.4 | 92.8 | 11.6 | −9.6 |

| Auto Transplant 2(post-op) | 107.0 | 94.0 | 12.9 | −10.0 |

| Allotransplant 1 Donor April (20 kg) | 101.2 | 83.8 | 17.5 | −13.9 |

| Allotransplant 1 Recipient (15 kg) | 110.6 | 81.1 | 29.6.0 | −12.1 |

| Allotransplant 1 Post-Op Recipient | 111.9 | 71.4 | 40.4 | −14.1 |

| Allotransplant 2 Donor (23.1 kg) | 99.0 | 89.0 | 9.0 | −11.8 |

| Allotransplant 2 Recipient (20.0 kg) | 108.6 | 83.5 | 25.1 | −10.5 |

| Allotransplant Post-Op Recipient | 109.2 | 80.7 | 28.5 | −8.5 |

Native Cephalometric Values

A total of eight native skulls were evaluated with cephalometry pre- operatively, and four hybrid swine skulls were evaluated post-operatively (N = 4 surgeries). The range of normal values for PA-PRN-ALV (human SNA correlate) for native swine skulls was 97.0° to 110.6°. The mean PA-PRN-ALV value of native swine skulls was 104.0°. The range of normal values for PA-PRN-LIB (human SNB correlate) for native (non-operated) swine skulls was 81.1° to 94.7°. The mean PA-PRN-LIB value of native swine skulls was 88.3°. The range of normal values for ALV-PRN-LIB (human ANB correlate) for native swine skulls was 3.1° to 25.1°. The mean ALV-PRN-LIB value of native swine skulls was 14.5°. The range of normal values for the angle of PA-PRN to Occlusal Plane for native swine skulls was −9.6° to Ȣ16.6°. The mean angle of PA-PRN to Occlusal plane value in native swine skulls was −12.5°.

Post-operative Cephalometric Values

Autotransplant Scenarios

The first and second Le Fort III autotransplant scenarios resulted in retained class I occlusion (defined as the mesio-buccal cusp of the swine’s maxillary first molar aligned over the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar) (Fig. 16A). Postoperatively, the mean change in PA-PRN-ALV angle was +2.25°, the mean change in PA-PRN-LIB was +0.65°, and ALV-PRN-LIB change was minimal at −1.75°. The angle of PA-PRN to the occlusal plane also remained relatively stable with a mean change of only +1.4° post-operatively.

Figure 16.

Schematic diagram showing various levels of Le Fort-based osteotomies in swine for pre-clinical investigation. Printed with Permission from Anastasia Demson, M.A.

Size-Mismatched Allotransplants

Following the completion of two autotransplants and simultaneous validation of reproducible post-operative cephalometric data points in swine, we proceeded with performing significant size mismatched allotransplants. The difference in weight between donor and recipient for the first and second transplant scenarios was +5 and +3.1 kg respectively. The difference in pre-operative and post-operative values for PA-PRN-ALV (analogous to human cephalometric SNA) in allotransplant 1 and 2 were +1.3° and +0.6° respectively. The difference in pre-operative and post-operative values for PA-PRN-LIB (analogous to human cephalometric SNB) in allotransplant 1 and 2 were −9.7° and −2.8°, respectively. The difference in pre-operative and post-operative values for ALV-PRN-LIB (analogous to human cephalometric ANB) in allotransplant 1 and 2 were +19.8° and +3.4° respectively. As in the autotransplant scenario, the PA-PRN to Occlusal Plane angle remained relatively stable post-operatively in the first and second allotransplant scenarios at −2.3° and −2.0° respectively (Table 3) (Fig. 16B).

DISCUSSION

Face transplantation techniques have evolved from myocutaneous alloflaps to those of osteomyocutaneous design including the maxilla, nasal bones, zygomas and mandible.1 In a properly selected candidate, a maxillofacial transplant can be a viable reconstructive option in the management of complex mid-facial defects where autologous reconstructive methods provide suboptimal results. Le Fort-based alloflaps provide not only aesthetic restoration of the facial contour (such as the nose and cheeks) but also restore proper facial dimensions/buttress support, viable teeth, and pertinent functions in the form of facial expression, nasopharyngeal airway patency, restoration of respiratory inflow for olfactory sense, orbital reconstruction, and mastication (Fig. 17).2

Figure 17.

Bird’s eye view of dorsal maxillary interface between donor alloflap and recipient. Note the significant dorsal step-off deformity at the area of osteosynthesis, which represents a significant size-mismatch and need to assess pre-operatively with virtual technology.

Donor-recipient matching in regards to facial size, soft-tissue features, skin color and texture has been shown to be essential for complete facial harmony post-transplant.14,15 To date however, all of the reported Le Fort-based, single-jaw transplants have been found to have some degree of dento-facial-skeletal discrepancies post-transplant with some patients requiring orthognathic surgery. This has been manifested as sub-optimal donor maxilla-recipient mandibular (e.g. hybrid) occlusion and craniofacial skeletal height deficiencies.2 While face transplant surgeons try to match donor-recipient characteristics as closely as possible, rarely can a perfect size match be obtained. This limitation could be partially or fully addressed with computer aided pre-operative planning, allowing for customized surgical techniques and guides, in order to achieve simultaneous soft (skin, muscles and fat) and hard tissue (skeleton and teeth) aesthetic harmony.10,15,16 With this in mind, our laboratory began a translational large animal orthotopic study in July 2011.10

Use of the swine as a large animal model for orthognathic and other craniofacial surgery is well described in the literature. Anthropometric studies have found the relationship of craniofacial structures such as the pterygoid plates, palatine bones, and maxillary tuberosities, to have a similar relationship in the swine as in the human.6–8 Given these homologous relationships, the swine may be the ideal translational large-animal medium to investigate various surgical strategies and improvements, such as pre-operative cephalometric planning using three-dimensional computed tomographic reconstruction, live intra-operative image guidance systems, fixation plating strategies, and improved cutting guide design and fabrication (Fig. 18). The goal of developing the aforementioned technologies was to achieve a more ideal post-transplant, donor-recipient craniofacial relationship in swine, which could be successfully translated to the human scenario for various types of complex craniomaxillofacial surgery in both children and adults (see Video, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which demonstrates Le Fort-based, maxillofacial transplantation in size-mismatched swine, and pre-operative planning with computer-assisted technology and custom surgical guide fabrication, available in the “Related Videos” section of the Full-Text article in PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users available at “insert hyper link” (Video graphic 1)).

Figure 18.

Facial alloflap, prior to inset. Real-time surgical navigation hardware attached to bony component of flap.

In designing our study, we first chose to evaluate which craniofacial landmarks would be affected by Le Fort-based facial transplantation. Pre and post-operative measurements were taken, with their results shown in Tables 1–3. In our study, several landmarks were identified which met the criteria of 1) being readily identifiable pre-operatively and intra-operatively with use of computer-aided surgical navigation, 2) conserved post-operatively allowing for accurate cephalometric analysis of post-operative results, and 3) sharing homologous characteristics with the human cranium (Table 1).

A secondary goal of this study was to determine if we could re-establish the swine’s native maxillary-mandibular relationship after performing Le Fort III-based surgery. Our initial autotransplants showed that several useful craniofacial landmarks could be preserved, with relatively close approximation to the native relationship, despite significant craniofacial disruption during transplantation (Fig. 16, Tables 1,2). However, we also found that, even in the autotransplant scenario, pre and post-operative Le Fort-based alloflap placement could be improved by performing computer-assisted surgery, pre-operative cephalometric analysis, and employing pre-fabricated cutting guides designed specifically with integrated tracking spheres (Fig. 19).

Figure 19.

Immediate post-operative photogragh following successful alloflap inset with adequate perfusion.

Such improvement can be seen when comparing pre- and post-autotransplant values of PA-PRN-ALV (SNA analog). Table 3 shows post-operative values of PA-PRN-ALV (SNA analog) in the autotransplant scenarios differing by an average of +2.25°. When pre-surgical cutting guide fabrication and intra-operative live surgical navigation were utilized in the size mis-matched transplant scenario, recipient and hybrid PA-PRN-ALV discrepancy decreased by 58% to only +0.95° when compared to the non-computer assisted, manual reduction. However, this trend in decreased pre and post-operative discrepancy did not hold for the other values of PA-PRN-LIB (SNB analog), ALV-PRN-LIB (ANB analog), or PA-PRN to Occlusal Plane angle when compared to the autotransplant scenarios in Table 3. The increased discrepancies in these values are more attributable to size mismatch than operative technique due to the fact that the 5 kg swine mismatch had a larger discrepancy in all three of the aforementioned values than the 3.1 kg size mismatched transplant.

Furthermore, when comparing the post-operative discrepancy between PA-PRN to Occlusal Plane in the autotransplant scenario (where manual reduction of the flap was performed) and the allotransplant scenario, (where cutting guides and real-time intraoperative navigation were implemented) the difference was only 0.43°. This illustrates the ability for this technology to maintain some near native maxillary-mandibular relationship values (PA-PRN-ALV) & (PA-PRN to Occlusal Plane) even in the case of significant size discrepancy. Compared to prior swine studies employing a single swine model for pre-clinical craniofacial investigation, we felt that only a transplant scenario between two size-mismatched swine (pairing based on swine leukocyte antigen (SLA)-matching) would be able to provide enough anatomical discrepancies to develop enhanced applications and techniques, and to fully test the technology.8,17,18 Future studies will compare size-matched and size-mismatched transplants to evaluate the degree of difference this variable contributes to maxillary-mandibular relationship. We will continue development of computer aided surgery with implementation of intra-operative dynamic cephalometrics to provide on-table prediction of maxillary-mandibular relationships, and prove the superior accuracy that computer-aided planning may offer the craniofacial surgeon.

In defining the relevant cephalometric points, we have established a basis upon which these peri-operative planning techniques and software technology can be improved, and future results validated. A limitation of the approach described herein is the reliance on two-dimensional landmarks. Although the surgical planning was completed using three-dimensional imaging techniques, cephalometric analyses were completed using the standard, two-dimensional sagittal view. Our purpose in this regard was to identify reproducible landmarks in the sagittal plane for planning and outcome assessment. Now that we have established that such landmarks are identifiable, our next step will be to identify and validate three-dimensional cephalometric landmarks.

CONCLUSION

Morphological similarities between swine and humans have been previously suggested that the swine is the optimal translational medium for Le Fort-based maxillofacial allotransplantation. In this study, we identified a new set of reliable cephalometric data points and measurements pertinent for the translational investigation of swine and for utilization within a pre-clinical large animal model. The use of these craniomaxillofacial landmarks in swine as related to humans, for surgical evaluation and technique development, seem critical for the innovation of computer-enhanced technologies, improved cutting guides, and ability to explore new avenues for investigation and collaboration.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental digital content Legend

Video Graphic 1 – See video 1 - Video documentary demonstrating Le Fort-based, maxillofacial transplantation in size-mismatched swine, and pre-operative planning with computer-assisted technology and custom surgical guide fabrication, available in the “Related Videos” section of the Full-Text article in PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users available at “insert hyper link”.

Figure 2.

Lateral cephalogram of large native swine skull with cephalometric markings and outlinings of first molars.

Acknowledgments

Outside funding from various grants were used for a portion of this study. This includes grant support by the American Society of Maxillofacial Surgery’s (2011 ASMS Basic Science Research grant), American Association of Plastic Surgeons (2012–14 Furnas’ Academic Scholar Award), and the Accelerated Translational Investigational Program at Johns Hopkins (funded by the National Institute of Health).

This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS or NIH [NCATS grant # UL1TR000424-06].

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or endorsement of the Department of the Navy, Army, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors have conflicts of interest, commercial associations or financial disclosures to report for this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon CR, Susarla SM, Peacock ZS, et al. Osteocutaneous maxillofacial allotransplantation: lessons learned from a novel cadaver study applying orthognathic principles and practice. Plast Recon Surg. 2011;128:465e–479e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b6949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon CR, Susarla SM, Peacock ZS, Kaban LB, Yaremchuk MJ. Le Fort-based maxillofacial transplantation: current state of the art and a refined technique using orthognathic applications. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:81–87. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240ca77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siemionow M, Papay F, Alam D, et al. Near-total human face transplantation for a severely disfigured patient in the USA. Lancet. 2009;374:203–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pomahac B, Pribaz J, Eriksson E, et al. Restoration of facial form and function after severe disfigurement from burn injury by a composite facial allograft. Amer J Transplant. 2011;11:386–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorafshar AH, Bojovic B, Christy MR, et al. Total face, double jaw, and tongue transplantation: an evolutionary concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:241–251. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182789d38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farkas LG, Munro IR, Vanderby BM. Quantitative assessment of the morphology of the pig's head used as a model in surgical experimentation. Part 1: Methods of Measurements. Canad J of Compar Med. 1976;40:397–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farkas LG, James JS, Vanderby BM. Quantitative assessment of the morphology of the pig's head used as a model in surgical experimentation part 2: results of measurements. Canad J of Compar Med. 1977;41:455–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castano FJ, Troulis MJ, Glowacki J, Kaban LB, Yates KE. Proliferation of masseter myocytes after distraction osteogenesis of the porcine mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:302–307. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.21000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swindle MM. Swine in the Laboratory: Surgery, Anesthesia, Imaging, and Experimental Techniques. CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group); 2007. pp. 274–275. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon CR, Swanson EW, Susarla SM, Coon D, Rada E, Al Rakan M, Santiago GF, Shores JT, Bonawitz SC, Fishman E, Murphy R, Armand M, Liacouras P, Grant GT, Brandacher G, Lee WPA. Overcoming cross-gender differences and challenges in Le Fort-based, craniomaxillofacial transplantation with enhanced computer-assisted technology. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;71(4):421–428. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182a0df45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otake Y, Armand M, Armiger R, Kutzr M, Basafa E, Kazanzides P, Taylor R. Image-based Multi-view 2D/3D Registration for Image-guided Orthopaedic Surgery: Incorporation of Fiducial-based C-arm Tracking and GPU-acceleration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31(4):948–962. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2176555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armiger R, Armand M, Lepisto J, Minhas D, Tallroth K, Mears s, Waites M, Taylor RH. Evaluation of a Computerized Measurement Technique for Joint Alignment Before and During Periacetabular Osteotomy. J Computer Aided Surg. 2007;12(4):213–224. doi: 10.1080/10929080701541855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulusal BG, Ulusal AE, Ozmen S, Zins JE, Siemionow MZ. A new composite facial and scalp transplantation model in rats. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Oct;112(5):1302–1311. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000079823.84984.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon CR, Siemionow M, Papay F, et al. The world's experience with facial transplantation: what have we learned thus far? Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:572–578. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181ba5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bojovic B, Dorafshar AH, Brown EN, et al. Total face, double jaw, and tongue transplant research procurement: an educational model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Oct;130(4):824–834. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318262f29c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown EN, Dorafshar AH, Bojovic B, et al. Total face, double jaw, and tongue transplant simulation: a cadaveric study using computer-assisted techniques. educational model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(4):815–823. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318262f2c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pomahac B, Aflaki P, Nelson C, Balas B. Evaluation of appearance transfer and persistence in central face transplantation: a computer simulation analysis. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery. J Plast Recon Aesth Surg. 2010;63:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadaki ME, Troulis MJ, Glowacki J, Kaban LB. A minipig model of maxillary distraction osteogenesis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(11):2783–2791. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.06.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gateno J, Seymour-Dempsey K, Teichgraeber JF, et al. Prototype testing for a new bioabsorbable Le Fort III distraction device: a pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(12):1517–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental digital content Legend

Video Graphic 1 – See video 1 - Video documentary demonstrating Le Fort-based, maxillofacial transplantation in size-mismatched swine, and pre-operative planning with computer-assisted technology and custom surgical guide fabrication, available in the “Related Videos” section of the Full-Text article in PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users available at “insert hyper link”.