Abstract

The cascade of HIV care in the United States has become a focus for interventions aimed at improving the success of HIV treatment. The Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) Infectious Disease Clinic (IDC) is an urban clinic that provides care for over 1,400 people living with HIV (PLHIV) annually. Using data from the HIV Atlanta VA Cohort Study (HAVACS), we modeled the continuum of care in the AVAMC IDC and explored similarities and differences with national models. We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 1,474 individuals receiving care in the AVAMC IDC. We estimated total PLHIV and defined several categories within the spectrum of HIV care. We then developed the continuum of care using two methodologies. The first required each stage to be a dependent subset of the immediate upstream stage. The second allowed each stage to be independent of upstream stages. Dependent stage categorization estimated that 95.3% of individuals were diagnosed with HIV, 89.8% of individuals were linked to care, 73.0% of individuals were retained in care, 65.9% of individuals were eligible for antiretroviral treatment (ART), 62.8% were prescribed ART, and 52.4% had a suppressed viral load (VL). Independent stage categorization estimated that 83.9% of individuals were prescribed ART and 61.5% had a suppressed VL. Our analyses showed that the AVAMC IDC estimates were significantly better than national estimates at every stage. This may reflect the benefits of a universal healthcare system. We propose the use of independent stages for the continuum as this more accurately represents healthcare utilization.

Introduction

Over 34 million individuals are estimated to be living with HIV worldwide,1 including approximately 1.2 million individuals in the United States by the end of 2010.2 The CDC estimates that new infections number 50,000 annually.3 New infections, however, account for a smaller percentage of the total number of people living with HIV (PLHIV) every year due to the increase in survival for individuals engaged and retained in HIV treatment and care. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is still the mainstay of treatment and has increased in availability, potency, and tolerability resulting in a decrease of morbidity and mortality over the past 15 years.2,4 HIV infection has become a manageable, chronic disease where most PLHIV prescribed and adhering to ART achieve undetectable plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL).5 Although the rate of HIV-related death has greatly decreased since 1996, HIV/AIDS is still a significant source of mortality in the United States. Despite the aforementioned improvement of ART and recent implementation of aggressive test-and-treat strategies, approximately 18,000 AIDS deaths still occurred in 2009.2,6

Recent analyses suggest that virologic suppression, an indicator of HIV treatment success, is achieved through progression along a continuum of HIV care.7 However, two national models have shown that there has been a failure of a significant percentage of PLHIV to progress to the next step in the continuum, with respective estimates of 19% and 25% virologic suppression among PLHIV in the United States.8,9 This has resulted in the continuum of HIV care becoming a focus for introduction of interventions aimed at improving the delivery of care for PLHIV.10

The Department of Veterans' Affairs (VA) is one of the largest providers of HIV care, with over 25,000 PLHIV having at least one visit in 2011.11 As of 2012, recently presented data showed that approximately 75.7% of all VA patients diagnosed with HIV between January 1998 and December 2008 were linked to care within 90 days of a positive HIV test and 84% were retained in care.12 This level of retention was significantly better than those reports on the general population and was associated with improved clinical outcomes and survival for individuals retained in care. The Atlanta Veterans' Affairs Medical Center (AVAMC) Infectious Disease Clinic (IDC) is an urban HIV clinic that annually provides care for approximately 1,500 PLHIV who reside primarily in northern Georgia, but including some patients from Alabama and South Carolina. Using data from the HIV Atlanta VA Cohort Study (HAVACS), we were able to model the continuum of care in a system where institutional barriers are significantly reduced for a population whose individual barriers parallel those found in the general population (e.g., unemployment, homelessness, substance use disorders, depression), and explore the similarities and differences with the national models.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Individuals included in this cross-sectional analysis were AVAMC IDC patients with Outpatient Status (OS) as of December 31, 2012 or patients who received an HIV diagnosis at AVAMC in 2012. OS is a designation given to patients seen at least once ever in the AVAMC IDC who are not known to be dead, under the care of another VA, receiving care outside the VA system, or ineligible for VA care. All PLHIV, regardless of diagnosis date, who separated from the Active Duty military with an honorable discharge are eligible for AVAMC care. Demographic and clinical data from 2012 were used in the analyses and were gathered from a number of sources including the HAVACS database (a computerized data warehouse used to follow IDC patients at AVAMC since 1982). Missing, noncurrent, or data not included in the HAVACS database were extracted from electronic medical records.

Definitions

Patients were stratified into each of seven categories of the continuum of care using the following definitions and methods of estimation. (1) A mathematical back-calculation model was used to estimate the total number of individuals living with HIV. The number of undiagnosed PLHIV was estimated by applying the 2012 AVAMC HIV-positive test rate of 0.15% (28 individuals tested positive out of 18,212 total individuals tested for HIV at AVAMC in 2012) to the 48,079 (55% of the total AVAMC patient population) patients not previously tested at the AVAMC. To estimate the total HIV infection prevalence, the estimated number of undiagnosed individuals was summed with the known number of diagnosed individuals. (2) HIV-diagnosed individuals were defined as those with OS who had a reported date of a positive HIV test in the HAVACS database as of December 31, 2012. (3) Patients linked to HIV care were defined as those diagnosed with HIV who had ever had an AVAMC IDC medical visit. A medical visit is defined by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) as a visit with a provider with prescribing privileges.13 (4) Patients retained in care were defined as those who had an AVAMC IDC medical visit within the 8 months prior to December 31, 2012. (5) ART eligible patients were those that ever had a CD4 count <500 cells/mm3. (6) The number of patients prescribed ART was determined by chart review. (7) The last category was PLHIV, who were virologically suppressed. Virologic suppression was defined as having the most recent VL in 2012 <200 copies/ml. Patients with viral loads prior to 2012 were assumed not to have virologic suppression in the analyses.

Two methodologies were used to categorize patients into stages of the continuum of care. First, patients were stratified into all seven defined stages as dependent subsets of upstream stages in the continuum of HIV care (the “dependent” cascade). In this method, patients were not eligible for progression to downstream stages if they did not meet criteria specified in the definitions for all of the stages upstream of a particular stage. Second, patients were stratified into four stages independent of whether they were included in a previous stage: individuals diagnosed with HIV, individuals linked to care, individuals prescribed ART, and individuals who achieved virologic suppression (the “independent” continuum). Patients were not required to meet criteria for any of the upstream stages in the continuum of HIV care to be eligible for categorization into any of the downstream stages. Proportions were expressed as a percentage of each category among the total estimated population of individuals with HIV.

Bivariate analyses of the “dependent” cascade stratified by key demographics (age, race, and HIV transmission risk factor exposure) were conducted. Also, the “dependent” cascade was compared to the existing national models of the cascade of HIV care.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses were performed with use of SPSS Statistics 17.0 Software, Release 17.0.0 (August 23, 2008. Chicago, IL). Chi-squared tests were used for comparison of categorical variables, and independent t-tests were used for comparison of continuous variables. p values of less than 0.05 were accepted as significant.

Results

Demographic data

In 2012 AVAMC served a total of 87,416 unique patients including 1,474 AVAMC IDC outpatients. Of these AVAMC IDC outpatients, 96.9% were male and 3.1% were female. The median age was 52.6 years with an interquartile range of 45.9 years to 59.5 years. Among outpatients, the racial/ethnic groups represented included African-American/black (77.8%), caucasian/white (19.9%), and other or unreported racial/ethnic groups (2.4%). HIV transmission risk factors among patients included men who have sex with men (MSM) (54.6%), injection drug users (IDU) (9.3%), individuals who have sex with the opposite gender with known HIV contact (6.3%), and other or unreported risk factors (29.8%).

The AVAMC continuum

The mathematical model described estimated that in 2012 there were 72 individuals living with HIV who were not diagnosed, increasing the total estimate for the number of PLHIV and receiving care in the AVAMC at 1,546. Using the definitions specified in Materials and Methods, the 1,474 outpatients were placed into categories of the continuum of HIV care.

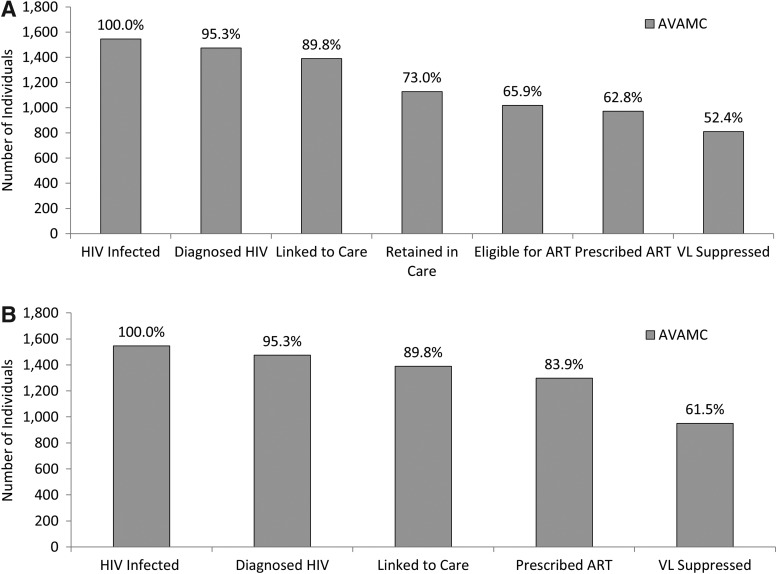

When patients were categorized into cascade stages as dependent subsets of upstream stages, proportions of the estimated AVAMC PLHIV in the six downstream stages in the continuum of HIV care specified in this analysis were as follows: 95.3% of individuals were diagnosed with HIV, 89.8% of individuals were linked to care, 73.0% of individuals were retained in care, 65.9 % of individuals were eligible for ART, 62.8% of individuals were prescribed ART, and 52.4% of individuals had a suppressed VL in 2012 (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Estimated numbers of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and receiving care in the Atlanta Veterans' Affairs Medical Center (AVAMC) (n=1,546) who are engaged in the stages of the cascade of HIV care in 2012 requiring sequential success in each cascade stage for progression through stages. (B) Estimated numbers of PLHIV and receiving care in the AVAMC (n=1,546) who are engaged in selected stages of care not requiring sequential success in stages to progress through stages of the continuum. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ART, antiretroviral therapy; VL, HIV viral load.

When patients are categorized into continuum stages independent of upstream stages, proportions of estimated AVAMC PLHIV in four selected downstream stages in the continuum of HIV care were as follows: 95.3% of individuals were diagnosed with HIV, 89.8% of individuals were linked to care, 83.9% of individuals were prescribed ART, and 61.5% of individuals had a suppressed VL (Fig. 1B). Independent estimates of those prescribed ART and those achieving virologic suppression were 21.1% higher and 9.1% higher, respectively, than the same stages as dependent subsets of upstream stages (p<0.0001).

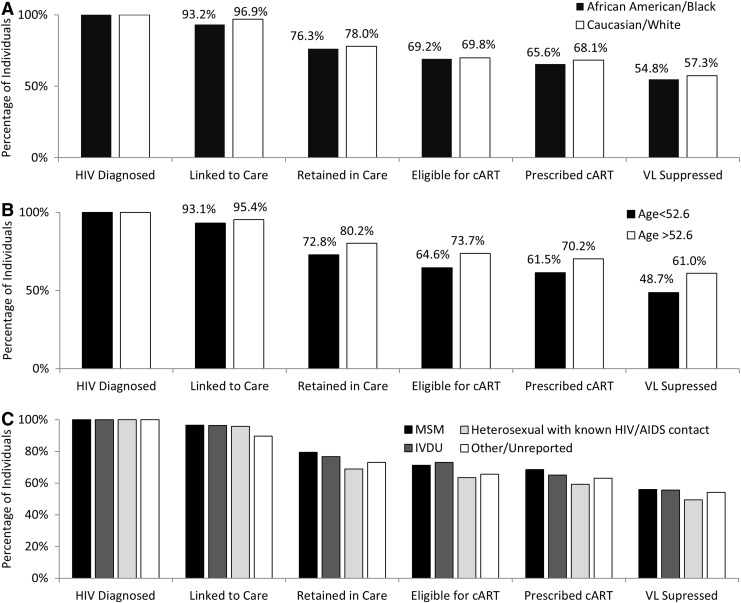

Patients were also stratified into categories as dependent subsets of upstream stages and separated by race/ethnicity, age, and HIV transmission risk factor (Fig. 2). White patients had a 2.5% higher rate of ART prescription (p<0.001) and a 2.5% higher rate of viral suppression (p<0.001) than black patients. Patients older than the median age (52.6 years) had an 8.7% higher proportion of ART prescription (p=0.032) and a 12.3% higher rate of VL suppression than patients below the median age (p=0.001). There were no significant differences among stages stratified by HIV transmission risk factors.

FIG. 2.

Proportions of individuals diagnosed with HIV and receiving care at the Atlanta Veterans' Affairs Medical Center (AVAMC) who are engaged in selected stages of the cascade of HIV care in 2012 separated by race (A), age (B), and HIV transmission risk factor (C). Each cascade stage is a dependent subset of the upstream stages. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; ART, antiretroviral therapy; VL, HIV viral load; MSM, men who have sex with men; IDU, injection drug user.

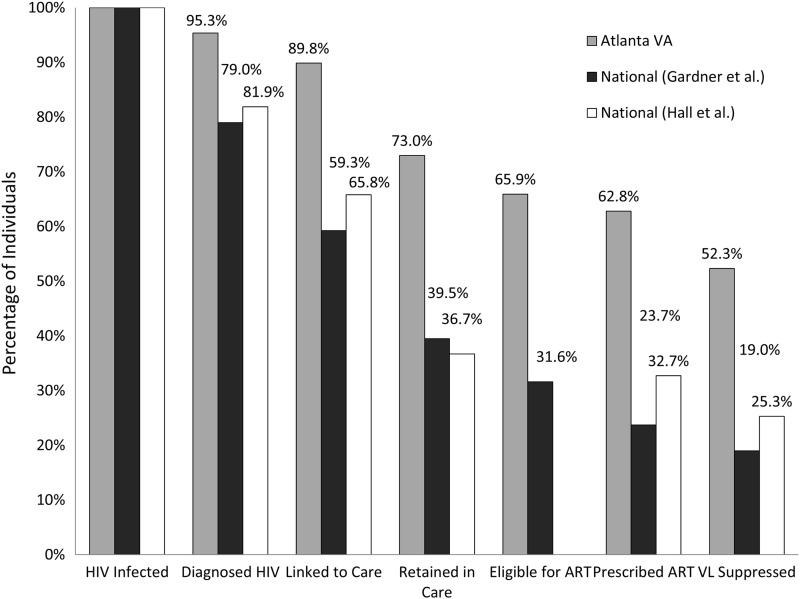

When the AVAMC cascade of HIV care proportions were compared to proportions based on the existing national models presented by Gardner et al.8 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Fig. 3), the AVAMC model had statistically greater proportions in all stages of the cascade (p<0.001). The AVAMC IDC VL suppression rate of 52.3% was 33.3% higher than the national estimate presented by Gardner et al.8 and 27.0% higher than the national estimate presented by Hall et al.9 (p<0.001).

FIG. 3.

Proportions of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and receiving care at the Atlanta Veterans' Affairs Medical Center (AVAMC) who are engaged in selected stages of the continuum of HIV care where stages are dependent subsets of upstream stages (gray) vs. National proportions of HIV-infected individuals engaged in selected stages of the cascade of HIV care as estimated by Gardner et al. (black) and Hall et al. (white).8,9 HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ART, antiretroviral therapy; VL, HIV viral load.

Discussion

The AVAMC had an extremely high estimated rate of HIV diagnosis (95.3%) and linkage to HIV care (89.8%) among individuals living with HIV. The high estimated rate of diagnosis is likely due to proactive testing policies within the AVAMC, with 45% of all AVAMC patients tested for HIV before the end of 2012. Most of this increase occurred after HIV testing became opt-out with only verbal consent required; in addition, a “clinical reminder” was introduced into the electronic medical record in 2009 to encourage increased testing. Among AVAMC PLHIV in 2012, overall 83.9% were prescribed ART and 61.5% had a suppressed VL. These improved values relative to national estimates could be due to a significant reduction in institutional barriers to treatment experienced by VA patients, which is inherent in an integrated healthcare system where costs are relatively low depending on income and eligibility criteria, ranging from no cost to minimal cost for visit and medication co-pays. Alternatively, other factors related to their military service or the social capital afforded veterans may provide some advantage that is not readily apparent. Despite the VA population exhibiting high rates of unemployment, homelessness, depression, and substance use disorders similar to other urban clinics, VA patients generally experience fewer interruptions in care related to life changes and incur minimal expenses related to HIV care.14,15 Finally, the VA healthcare system provides seamless access to electronic medical record data across the United States, and most patients with HIV receive the majority if not all of their care at a VA. This allows for improved continuity of care for patients as well as a more accurate and real-time assessment of the continuum due to availability of data.

When considering demographic variables, it appeared that white patients had slightly higher rates of ART prescription and viral suppression than black patients. These differences, while very small, were consistent with published trends.16 In a previous study conducted in an urban clinic in northern California with demographics similar to the AVAMC IDC, no disparity for the risk of clinical events including progression to AIDS and death for racial/ethnic minorities was observed despite lower rates of ART adherence among minorities; however, comparisons between studies are limited due to the fact that the authors performed an adjusted analysis.17 Patients older than the median age had significantly higher rates of ART prescription and VL suppression. The 8.7% difference in ART prescription rates could be due to the fact that younger patients are more likely to be recently diagnosed and are not yet eligible for ART (a 9.1% difference), whereas the larger 12.3% difference in viral suppression rates could be due to poorer adherence in younger patients.18 Because analyses of demographic variables were bivariate, these conclusions are subject to possible confounding from unconsidered variables.

Analysis of the stages of the continuum of HIV care using two different methods was done both to maintain congruency with methods used in national models and because the idea was recently introduced that requiring upstream cascade stage success for progression to the later stages underestimates rates of prescription of ART and viral suppression.19 The 21.1% greater proportion of those prescribed ART in the “independent” continuum in the AVAMC could be due to the fact that IDC patients are able to telephone in ART prescription refills for a longer period than the period between treatment visits and despite not having had a recent medical visit, remain adherent on ART and potentially achieve virologic suppression. Some IDC patients could also be receiving ART from a source outside of the AVAMC as well, which technically would increase the percentage of patients retained in care. The 9.1% difference in VL suppression rates between methodologies is likely secondary to the higher estimated rate of ART prescription. We ultimately believe this “independent” approach is a more accurate assessment of reality since individual patients may engage in only certain aspects of the continuum of care at any given period of time but could still achieve the goal of virologic suppression.

These analyses are subject to certain limitations. First, denominators vary among several reports of local and national models of the cascade of care. Despite the national estimate of undiagnosed HIV infection being 18.1%, we believe that this estimate would be inaccurately high if applied to the AVAMC given the proactive local testing policies in place. By using the 2012 AVAMC HIV seropositive rate to estimate the undiagnosed HIV infection rate at approximately 4.9%, we believe that our model would be a more accurate representation of the actual AVAMC continuum. Still, the estimate of 72 undiagnosed AVAMC PLHIV is likely a conservative estimate of the true number of undiagnosed PLHIV in the AVAMC due to the fact that most individuals who were not tested probably had a lower risk of HIV infection than those screened or tested for suspicion of diagnosis. This could mean the true rates of diagnosis, linkage to care, retention in care, taking ART, and virologic suppression are higher than the rates estimated here.

That being said, 7 years after the passage of the Veterans' Healthcare reform act in 1996, which expanded eligibility for VA care, it was estimated that only 27.78% of veterans were enrolled in VA care.20 It would be extremely difficult to estimate the prevalence of HIV among all veterans and any attempts to do so were avoided in these analyses, as conclusions would be purely speculative. Second, in other published reports, definitions used to categorize patients into different stages of the continuum of care have varied considerably, specifically in the categories of linkage and retention. This limits the ability to make meaningful comparisons between the AVAMC model and other models of the continuum of care. It has been debated whether linkage to care should refer to patients having initial laboratory tests drawn or having an initial HIV medical visit. We chose a visit-based definition as a more conservative estimate of linkage and retention. However, it has recently suggested that linkage should be defined based on the long-term outcome of interest, with a laboratory-based definition being predictive of VL suppression and a visit-based definition predictive of retention in care.21

Retention in care has a tremendous amount of variation in definitions; however, we chose a dichotomous “gaps in care”-based measure due to ease of analysis, ease of measurement, and the lack of any clearly superior measure of retention.22 One effect using this measure of retention may have is an underestimate of those patients truly involved in regular care. As the data presented in this article show, 141 of the patients at the AVAMC IDC who have virologic suppression do not meet the specified visit-based definition for retention. It is likely that a laboratory-based definition would categorize some of these individuals as retained.

Despite extremely high AVAMC rates of ART prescription and VL suppression overall, still only 62.8% and 52.4% of individuals were both involved in regular care and prescribed ART or had a suppressed VL, respectively. While the AVAMC rates even requiring involvement in care are much better than the national estimates, there is still room for improvement in the AVAMC system. The largest difference between subsequent stages is between patients linked to care and patients retained in care (a difference of 16.8%), indicating that retention could be a focus for improvement in AVAMC. Despite the known benefits and recent practice guidelines' emphasis on increasing retention in HIV care,23,24 barriers to retention remain poorly understood.

In conclusion, we found high rates of diagnosis, linkage, retention, and virologic suppression for individuals receiving HIV care in the AVAMC when compared to national estimates. Our rates are likely higher due to the benefits of an integrated healthcare system and the access to more complete data. The exact percentages of persons in each of the levels of care vary considerably across previously published and presented studies, in part as a consequence of definitions and available data. We advocate using an “independent” approach to evaluating linkage, retention, and adherence to ART, as these aspects of care do not necessarily depend on each other. Conducting these assessments could be beneficial for programs and health departments to identify potential gaps in care and design interventions that aim to bridge those gaps, ultimately improving clinical outcomes for PLHIV.

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by Emory Center for AIDS Research (Grant P30 AI050409) and the Infectious Disease Society of America Medical Scholars Program. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Atlanta Veterans' Affairs Medical Center, Atlanta, GA.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS epidemic: 2012. 2012; www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf Accessed June13, 2012

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 U.S. dependent areas—2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2013;18(No. 2, part B). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2010_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_18_no_2.pdf

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2012.17. www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010supp_vol17no4/

- 4.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC Jr, et al. : Retention in care: A challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(11):1493–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. : Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365(6):493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. : Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-14):1–17; quiz CE11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eldred L. and Malitz F: Introduction. AIDS Patient Care Stds 2007;21:S1–S2 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, and Burman WJ: The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(6):793–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. : Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(14):1337–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office of National AIDS Policy: National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States; July2010

- 11.Department of Veterans' Affairs: The State of Care for Veterans with HIV/AIDS: 2011 Summary Report. www.hiv.va.gov/pdf/VA2011-HIVSummaryRpt.pdf Accessed June26, 2013

- 12.Department of Veterans' Affairs: HIV Care Quality Measures 2012. CCR Report. http://vaww.hiv.va.gov/data-reports/ccr-index.asp Accessed June10, 2013

- 13.Health Resources and Services Administration: HAB HIV Core Clinical Performance Measures Group 1. http://hab.hrsa.gov/deliverhivaidscare/files/habgrp1pms08.pdf Accessed May23, 2013

- 14.Guest JL, Weintrob AC, Rimland D, et al. : A comparison of HAART outcomes between the US Military HIV natural history study (NHS) and HIV Atlanta veterans affairs cohort study (HAVACS). PLoS One 2013;8(5):e62273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tate J: Personal communication with lead statistician for VACS. April10, 2012

- 16.Weintrob AC, Grandits GA, Agan BK, et al. : Virologic response differences between African Americans and European Americans initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy with equal access to care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52(5):574–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Quesenberry CP, Jr, and Horberg MA: Race/ethnicity and risk of AIDS and death among HIV-infected patients with access to care. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(9):1065–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weintrob AC, Fieberg AM, Agan BK, et al. : Increasing age at HIV seroconversion from 18 to 40 years is associated with favorable virologic and immunologic responses to HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;49(1):40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horberg M, Hurley L, Towner W, Gambatese R, Klein D, Antoniskis D, Kadlecik P, Kovach D, Remmers C, and Silverberg M: HIV spectrum of engagement cascade in a large integrated care system by gender, age, and methodologies. CROI, Atlanta, GA, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Distajo R, et al. : America's neglected veterans: 1.7 million who served have no health coverage. Int J Health Serv 2005;35(2):313–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller SC, Yehia BR, Eberhart MG, and Brady KA: Accuracy of definitions for linkage to care in persons living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63(5):622–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, et al. : Measuring retention in HIV care: The elusive gold standard. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61(5):574–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, et al. : Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: Evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med 2012;156(11):817–833, W-284–W-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, and Crepaz N: Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: A meta-analysis. AIDS 2010;24(17):2665–2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]