Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Maternal deficiency of the omega-3 fatty acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), has been associated with perinatal depression, but there is evidence that supplementation with eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) may be more effective than DHA in treating depressive symptoms. This trial tested the relative effects of EPA- and DHA-rich fish oils on prevention of depressive symptoms among pregnant women at an increased risk of depression.

STUDY DESIGN

We enrolled 126 pregnant women at risk for depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score 9–19 or a history of depression) in early pregnancy and randomly assigned them to receive EPA-rich fish oil (1060 mg EPA plus 274 mg DHA), DHA-rich fish oil (900 mg DHA plus 180 mg EPA), or soy oil placebo. Subjects completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview at enrollment, 26–28 weeks, 34–36 weeks, and at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum. Serum fatty acids were analyzed at entry and at 34–36 weeks’ gestation.

RESULTS

One hundred eighteen women completed the trial. There were no differences between groups in BDI scores or other depression endpoints at any of the 3 time points after supplementation. The EPA-and DHA-rich fish oil groups exhibited significantly increased post-supplementation concentrations of serum EPA and serum DHA respectively. Serum DHA- concentrations at 34–36 weeks were inversely related to BDI scores in late pregnancy.

CONCLUSION

EPA-rich fish oil and DHA-rich fish oil supplementation did not prevent depressive symptoms during pregnancy or postpartum.

Keywords: depression, docosahexaenoic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, fish oil, supplementation

Depressive symptoms are associated with significant morbidity in pregnancy and postpartum. Perinatal depression may be associated with impaired mother-infant bonding and may also be associated with adverse outcomes of pregnancy, such as preterm birth and low birthweight.1 Although antidepressant medications of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor category are readily prescribed, these medications have been associated with both major cardiovascular malformations and poor neonatal adaptation syndromes.2 For this reason, there has been interest to test alternative medicine modalities that might prevent or treat this debilitating condition without associated deleterious effects.

Over the past decade, there has been considerable interest in the omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), as possible preventive or therapeutic modalities for depression. In animal studies, dysregulation of the innate immune response has been associated with diets low in omega-3 fatty acids; this immune dysfunction has also been implicated in mood disorders.3 Human observational evidence has suggested that deficiency of DHA may predispose to perinatal depression.4,5 DHA is preferentially transferred from the maternal to fetal compartment in the third trimester of pregnancy, leaving many mothers relatively DHA deficient.6

Several early trials have suggested that fish oil supplementation may be beneficial in treating perinatal depression.7–9 However, several larger, blinded trials of maternal DHA supplementation have failed to show a benefit for this intervention.10–12 One potential reason for this disparity in the observational and interventional studies is that EPA rather than DHA may be the more active fatty acid in the prevention or treatment of mood symptoms. Three systematic reviews comparing DHA and EPA for the prevention or treatment of mood disorders among nonpregnant and pregnant individuals have suggested that EPA rather than DHA may have beneficial effects.13–15 Likewise, a recently randomized controlled trial comparing 1 g of EPA, 1 g of DHA, and coconut oil placebo for mild to moderate depression in nonpregnant individuals found EPA to be superior to DHA and placebo in treating depressive symptoms.16

We carried out this study to directly compare EPA-rich fish oil, DHA-rich fish oil, and soy oil placebo for the prevention of depressive symptoms among pregnant women at an increased risk for depression. We hypothesized that the EPA- or DHA-rich fish oil supplementation would reduce the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score at 6 weeks postpartum by 50% compared with placebo.

Materials and Methods

Details of ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan Health System (Ann Arbor, MI) and St Joseph Mercy Health System (Ypsilanti, MI). Enrolled participants provided written informed consent.

Study design

The protocol for this study has been previously described.17 We solicited permission to determine eligibility from pregnant women presenting for prenatal care at 2 health systems in southeastern Michigan: the University of Michigan Health System and St Joseph’s Mercy Hospital Health System. We used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a widely used 10 item measure of perinatal mood, to screen potential subjects for depression risk.18 Inclusion criteria included past history of depression, an EPDS score 9–19 (at risk for depression or mildly depressed), singleton gestation, a maternal age of 18 years or older, and a gestational age of 12–20 weeks. Potential subjects were excluded if they had a history of a bleeding disorder, thrombophilia requiring anticoagulation, multiple gestation, bipolar disorder, current major depressive disorder, current substance abuse, lifetime substance dependence, or schizophrenia. Women were also ineligible if they were currently taking omega-3 fatty acid supplements or antidepressant medications or eating more than 2 fish meals per week.

For a final determination of eligibility, study staff with training in clinical psychology administered the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). The MINI is a structured interview for diagnosis of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV and International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, psychiatric disorders.19 We used the MINI to exclude current major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, current substance abuse or dependence, suicidal ideation, or schizophrenia.17

Sample size considerations

Our sample size calculation was based on the premise that supplementation with either EPA-rich or DHA-rich fish oil would result in a 50% reduction in the mean BDI score at 6 weeks postpartum. The test characteristics of the BDI as a depression screen among pregnant populations have been well characterized.20,21 The BDI has been used in perinatal psychiatric studies as a measure of severity of depressive symptoms.22,23

Sample size calculations were generated in nQuery Advisor version 6.01 (STATCON, Witzenhausen, Germany). The sample size was chosen based on the expected BDI scores using postpartum BDI scores from a previous study of pregnant women.24 For this calculation we used a mean BDI score of 8.4 and SD of 6.4 expected among postpartum mothers at risk for depression. Assuming a significance level of P = .05, a 1-way analysis of variance test, a variance of means (variance of the individual group means) of 3.920, a SD of 6.4, and an effect size (the index of the separation expected among the observed means) of 0.0957, we planned to recruit 105 pregnant women (35 pregnant women in each of the 3 groups) to have 80% power to detect at least 1 group difference in the mean BDI score. The sample size was increased by 20% to account for anticipated study dropouts and women who were expected to start antidepressant treatment. Our decision to hypothesize a 50% reduction in the mean BDI score between intervention and control groups was based on results from published studies.7,8

Women who met all eligibility criteria and who agreed to participate were randomly assigned to receive one of the following: (1) EPA-rich fish oil supplementation (1060 mg EPA plus 274 mg DHA); (2) DHA-rich fish oil supplement (900 mg DHA plus 180 mg EPA); or (3) a soy oil placebo (control arm). Randomization was carried out using a random number table maintained in the University of Michigan Investigational Drug Service.

The intervention supplements and placebo were provided by Nordic Naturals Corporation in Watsonville, CA. The EPA-rich fish oil (ProEPAXtra, Nordic Naturals) contained an approximate 4:1 ratio of EPA to DHA (1060 mg EPA plus 274 mg DHA), whereas the DHA-rich oil (ProDHA, Nordic Naturals) contained DHA and EPA in an approximate 4:1 ratio (900 mg DHA plus 180 mg EPA). The placebos were formulated to be identical in appearance to both the EPA- and DHA-rich supplements and contained 98% soybean oil and 1% each of lemon and fish oil. The supplements were molecularly distilled and free of industrial contaminants, mercury, and organochlorines.

Because the EPA and DHA capsules were not identical in appearance, we used a double-dummy design to maintain blinding. The EPA group received 2 large EPA-rich fish oil capsules and 4 small placebo capsules formulated to appear identical to the DHA-rich fish oil capsules. The DHA group received 2 large placebo capsules formulated to appear identical to the EPA-rich fish oil capsules and 4 small DHA-rich fish oil capsules. The placebo group received 2 large and 4 small placebo capsules daily. Adherence to the protocol was assessed by self-report as well as by capsule counts. Subjects were asked to return unused capsules to study staff at each study visit. We also assessed omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acid levels before and after supplementation as a measure of compliance.

Enrolled subjects attended 4 study visits. The BDI and MINI were administered at each of these 4 time points: visit 1 at 12–20 weeks’ gestation, visit 2 at 26–28 weeks’ gestation, visit 3 at 34–36 weeks’ gestation, and visit 5 at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum. At visits 2, 3, and 5, the MINI was readministered to diagnose MDD. Subjects who met criteria for MDD at any time during study participation continued in the study but were also referred to mental health providers for standard care. Obstetrical and mental health providers were free to prescribe antidepressant medications, if indicated.

Maternal blood was drawn at enrollment as well and at 34–36 weeks’ gestation after a fast of at least 4 hours. Umbilical cord blood (mixed arterial and venous) was collected from infants born to mothers who participated in the study. All samples were centrifuged before separation into the 6 aliquots and were stored at −70 degrees C.

Fatty acid analyses were carried out on thawed serum aliquots. Total serum fatty acids were first extracted with Folch reagent and then converted to fatty acid methyl esters. Quantitation was done using gas chromatography with mass spectral detection as previously described.25 Results were expressed as percentage of total fatty acids.

The Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. For continuous variables, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare groups. The change in fatty acid levels was assessed using the paired Student t tests, the Wilcoxon signed rank test, and the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to evaluate the role of serum EPA and DHA as predictors of the BDI score.

This study’s identifier is NCT00711971.

Results

Between October 2008 and May 2011, 2657 women granted permission to determine eligibility and were screened for depression in early pregnancy. Of these, 161 women who met initial entry criteria underwent a final determination of eligibility with the MINI. Thirty-five women were excluded after undergoing the MINI, with reasons for exclusion being current major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and substance dependence. There were 126 women who enrolled in the study and who were randomly assigned to receive EPA-rich fish oil, DHA-rich fish oil, or placebo. There were 8 women who discontinued trial participation. One of the subjects in the DHA-rich fish oil group experienced a second-trimester pregnancy loss attributed to cervical insufficiency. The remaining 7 subjects were lost to follow-up and information was not available on the study outcomes for these subjects.

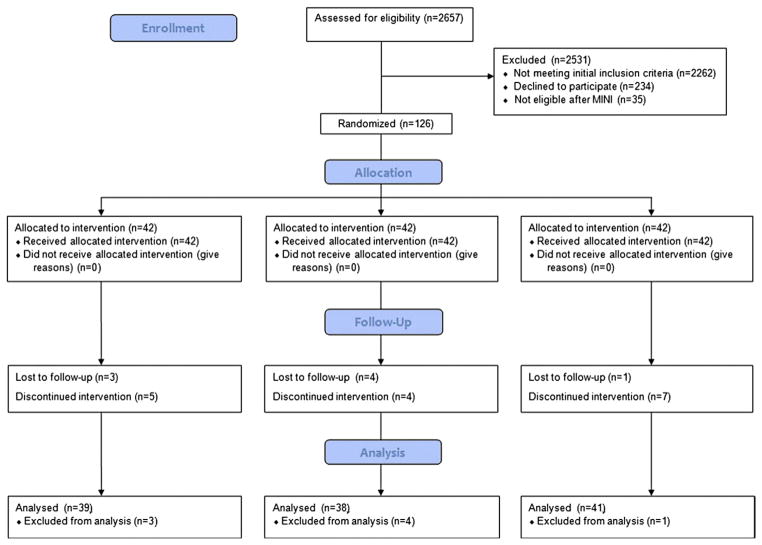

There remained 39 women who received EPA-rich fish oil, 38 women who received DHA-rich fish oil, and 41 women who received placebo supplementation. During the course of the trial, there were 16 ongoing subjects who discontinued taking the study supplement before the final study visit at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum. These subjects were analyzed in the intent-to-treat analysis. Reasons for discontinuation included side effects (mostly nausea, belching, and fishy aftertaste as well as forgetting to take capsules or becoming too busy to take study capsules). The Consort flow diagram of subject recruitment and participation is in the Figure. The baseline characteristics of the study participants are detailed in Table 1.

FIGURE. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 flow diagram.

This figure describes the recruitment and determination of eligibility process for this trial.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Parameter | EPA-rich fish oil (n = 39) | DHA-rich fish oil (n = 38) | Placebo (n = 41) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 29.9 (5.0) | 30.6 (4.5) | 30.4 (5.9) | .85a |

| Gestational age at enrollment (wks), mean (SD) | 15.9 (2.6) | 17.0 (2.3) | 16.2 (2.3) | .15a |

| Parity, mean (SD) | 0.87 (0.83) | 1.08 (0.94) | 0.85 (1.20) | .55a |

| Racial characteristics, n (%) | ||||

| White | 33 (85) | 29 (76) | 34 (83) | .49b |

| African-American | 4 (10) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | |

| Hispanic-Latina | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 3 (7) | |

| Asian | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific ethnicity | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Past history of depression (self-reported), n (%) | 32 (82) | 30 (79) | 33 (80) | .96b |

| Baseline BDI score, mean (SD) | 8.41 (5.65) | 7.79 (5.29) | 7.15 (5.21) | .58a |

| EPDS screen, mean (SD) | 7.93 (4.63) (n = 32) | 7.56 (4.49) (n = 32) | 7.34 (4.40) (n = 29) | .87a |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation.

One-way ANOVA;

Fisher exact test.

BDI scores at 34–36 weeks’ gestation and at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum were compared between groups in an ANCOVA with the baseline score as a covariate. There were no significant differences in the change in the BDI scores between enrollment and the 34–36 weeks’ gestation visit or the 6–8 week postpartum visit among the randomized groups. There were no differences in the mean BDI scores among the groups at entry or at any of the study visits after supplementation. There were no statistically significant differences among the groups in the proportion of women who started antidepressant medications or in antidepressant dose requirements (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Intent-to-treat analysis

| Parameter | EPA-rich fish oil (n = 39) | DHA-rich fish oil (n = 38) | Placebo (n = 41) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean BDI visit 2, n (SD) | 8.7 (4.2) | 7.0 (4.6) | 6.3 (3.9) | .051a |

| Mean BDI visit 3, n (SD) | 8.2 (5.7) | 6.9 (6.3) | 7.4 (5.5) | .81a |

| Mean BDI visit 5, n (SD) | 6.6 (5.2) | 5.7 (4.8) | 5.9 (6.1) | .78a |

| MDD visit 2, n (%) | 4 (10) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | > .16b |

| MDD visit 3, n (%) | 2 (5) | 4 (11) | 3 (7) | |

| MDD visit 5, n (%) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | |

| Started antidepressant, n (%) | 6 (15) | 7 (18) | 4 (10) | .56c |

| On lowest antidepressant dose, n (%) | 3 (50) | 7 (100) | 3 (75) [1 unknown dose] | .07c |

The BDI included scores in which 0–9 means minimal depressive symptoms, 10–19 means mild to moderate depressive symptoms, 20 or greater means moderate to severe depressive symptoms. Visit 2 was at 26–28 weeks’ gestation; visit 3 was at 34–36 weeks’ gestation; and visit 5 was at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation.

One-way ANOVA adjusted for BDI at enrollment;

Generalized estimating equation model;

Fisher exact test.

There were no significant differences in the proportion of subjects who complained of gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, belching, and fishy aftertaste) among the randomized treatment groups. There were no significant differences between the randomized groups in measures of adherence (Table 3). Based on self-reported adherence, a per-protocol analysis was carried out, excluding those subjects who reported stopping their capsules early (n = 16) and those whose capsule continuation was unable to be ascertained (n = 4). There were no significant differences in BDI scores in the per-protocol analysis (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Measures of capsule compliance

| Parameter | EPA-rich fish oil (n = 39) | DHA-rich fish oil (n = 38) | Placebo (n = 41) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stopped before visit 2 (self-report) | 3 | 0 | 3 | .24a |

| Compliance between visits 1 and 2 (pill count), mean (SD) [number missing]c | 0.67 (0.25) [3] | 0.78 (0.20) [4] | 0.68 (0.27) [1] | .15b |

| Stopped before visit 3 (self-report) | 4 | 2 | 4 | .77a |

| Compliance between visits 2 and 3 (pill count), mean (SD) [number missing]c | 0.58 (0.32) [5] | 0.65 (0.27) [6] | 0.63 (0.31) [2] | .63b |

| Stopped before visit 5 (self-report) | 5 | 4 | 7 | .75a |

| Compliance between visits 3 and 5 (pill count), mean (SD) [number missing]c | 0.67 (0.35) [4] | 0.62 (0.30) [2] | 0.64 (0.36) [3] | .85b |

Visit 1 was at enrollment at 12–20 weeks, visit 2 was at 26–28 weeks, visit 3 was at 34–36 weeks, and visit 5 was at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum. ANOVA, analysis of variance; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; SD, standard deviation.

Fisher exact test;

One-way ANOVA;

Missing means that the subject did not return capsules to be counted at this time point.

TABLE 4.

Per-protocol analysis

| Parameter | EPA-rich fish oil (n = 31), mean (SD) | DHA-rich fish oil (n = 33), mean (SD) | Placebo (n = 32), mean (SD) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI visit 2 | 7.9 (3.7) | 6.5 (4.7) | 6.3 (4.1) | .29a |

| BDI visit 3 | 7.4 (5.0) | 5.9 (4.9) | 7.2 (5.2) | .51a |

| BDI visit 5 | 6.6 (5.2) | 5.1 (4.4) | 6.2 (6.5) | .56a |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; SD, standard deviation.

One-way ANOVA controlling for BDI score at enrollment.

Supplementation significantly increased serum EPA in the EPA group and significantly increased serum DHA in the DHA-rich fish oil group (Table 5). To evaluate the relationship between maternal serum EPA and DHA and BDI scores at visits 3 and 5, we fit the following variables in an ANCOVA model: BDI at enrollment, group allocation, smoking, body mass index at enrollment, admission to having stopped taking capsules, admission to have started antidepressant medications, serum EPA at 34–36 weeks, serum DHA at 34–36 weeks, and total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids at 34–36 weeks.

TABLE 5.

Maternal fatty acids

| Group | Visit | Serum fatty acids | n | Mean | SD | Significance vs placeboa | Significance vs visit 1b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA-rich fish oil | 1 | EPAc | 42 | 0.29 | 0.18 | NS | — |

| DHAc | 42 | 4.24 | 2.30 | NS | — | ||

| Total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsd | 42 | 22.10 | 3.72 | NS | — | ||

| 3 | EPAc | 38 | 0.41 | 0.43 | NS | < .05 | |

| DHAc | 38 | 4.38 | 2.42 | NS | NS | ||

| Total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsd | 38 | 28.20 | 9.86 | NS | NS | ||

| DHA-rich fish oil | 1 | EPAc | 41 | 0.31 | 0.24 | NS | — |

| DHAc | 41 | 4.66 | 2.29 | NS | — | ||

| Total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsd | 41 | 24.91 | 7.73 | NS | — | ||

| 3 | EPAc | 37 | .38 | .23 | NS | NS | |

| DHAc | 37 | 6.05 | 3.77 | < .05 | < .05 | ||

| Total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsd | 37 | 36.41 | 9.71 | < .05 | |||

| Placebo | 1 | EPAc | 42 | .34 | .22 | — | — |

| DHAc | 42 | 3.85 | 1.77 | — | — | ||

| Omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsd | 42 | 22.86 | 5.02 | — | — | ||

| 3 | EPAc | 41 | 0.36 | 0.40 | — | NS | |

| DHAc | 41 | 3.70 | 1.62 | — | NS | ||

| Omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsd | 41 | 27.46 | 9.55 | — | NS |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test;

Student t test and signed rank test;

Expressed as percent of total fatty acids;

Expressed as percent of total highly unsaturated fatty acids.

The initial evaluation found the variables BDI at enrollment, admission to having stopped taking capsules, serum EPA, and serum DHA to be significant predictors of the BDI score at visit 3. Because of skewed distributions, we log transformed serum EPA and DHA values and performed regression analyses to evaluate the relationship of these variables with the BDI scores at visits 3 and 5.

Because EPA and DHA were highly correlated, they were modeled separately. The BDI score at visit 3 was significantly predicted by serum DHA (P < .05), BDI at enrollment (P < .001) and admission to having stopped taking capsules (P < .01). Serum DHA was inversely related to BDI scores. The model including DHA, BDI score at visit 1 and admission to having stopped capsules accounted for 31% of the variance in the BDI score at visit 3. Serum EPA did not significantly predict the BDI score at visit 3. Neither serum EPA nor DHA significantly predicted BDI scores at 6–8 weeks postpartum.

Supplementation with DHA-rich fish oil significantly lengthened gestation (40.4 weeks) compared with EPA (39.1 weeks) and placebo (39.1 weeks) (P < .0001) but did not result in significant differences in labor inductions. There were no significant differences in any other maternal outcomes (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Maternal outcomes

| Parameter | EPA-rich fish oil (n = 39) | DHA-rich fish oil (n = 38) | Placebo (n = 41) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery (wks), mean (SD) | 39.1 (1.5) | 40.4 (0.9) | 39.1 (1.5) | < .0001a–c |

| GDM, n (%) | 7 (18) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | .06d |

| Gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, n (%) | 8 (21) | 2 (5) | 5 (12) | .12d |

| Induced labor, n (%) | 15 (38) | 12 (32) | 8 (20) | .20d |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), mean (SD) | 507 (481) | 508 (325) | 454 (296) | .81a |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 10 (26) | 12 (32) | 11 (28) | .084d |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery, n (%) | 25 (64) | 25 (66) | 28 (70) | .88d |

| Operative vaginal delivery, n (%) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | .32d |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

One-way ANOVA;

Tukey’s studentized range test;

The DHA group was significantly greater than both the EPA group and the placebo group;

Fisher exact test.

There were 119 babies born to continuing trial participants, included 1 set of twins. The twin gestation was undiagnosed at the time of enrollment; both neonates were analyzed based on intent-to-treat principles. Supplementation resulted in higher birthweight in the DHA group compared with the EPA and placebo groups (P < .001). Five minute Apgar scores were significantly higher in the DHA group than the EPA and placebo groups combined, an effect without clinical significance. There were no differences in any other neonatal outcome measure among the groups (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Neonatal outcomes

| Parameter | EPA-rich fish oil (n = 40) | DHA-rich fish oil (n = 38) | Placebo (n = 40) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3402 (550) | 3774 (438) | 3309 (555) | < .001a–c |

| One minute Apgar, mean (SD) | 7.3 (2.2) | 7.9 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.9) | .19a |

| 5-minute Apgar, mean (SD) | 8.6 (0.8) | 9.1 (0.2) | 8.9 (0.5) | < .01a,d |

| Cord arterial pH, mean (SD) | 7.26 (0.09) (n = 34) | 7.27 (0.05) (n = 31) | 7.27 (0.06) (n = 31) | .54a |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 6 (15) | 2 (5) | 4 (10) | .39e |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; SD, standard deviation. Data are missing on 1 neonate who was not delivered at either study hospital.

One-way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test for outliers;

Tukey’s multiple comparisons test;

The DHA group was greater than both the EPA and placebo groups;

Mann-Whitney (Wilcoxon) test;

Fisher exact test.

Maternal DHA-rich fish oil supplementation significantly increased umbilical cord serum DHA proportion. Umbilical cord serum EPA and DHA concentrations in babies born to mothers who had received EPA-rich fish oil were not significantly different from umbilical cord serum concentrations from babies born to mothers in the placebo group (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

Fatty acids in umbilical cord serum, as percent of total fatty acids

| Group mean | SD | Significance vs placeboa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA (n = 33) | EPAb | 0.49 | 0.50 | NS |

| DHAb | 7.59 | 3.82 | NS | |

| Total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsc | 25.12 | 7.22 | NS | |

| DHA (n = 33) | EPAb | 0.43 | 0.34 | NS |

| DHAb | 9.94 | 4.82 | < .05 | |

| Total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsc | 29.87 | 7.04 | < .05 | |

| Placebo (n = 36) | EPAb | 0.50 | 0.49 | — |

| DHAb | 6.23 | 2.58 | — | |

| Total omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acidsc | 22.44 | 7.03 | — |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test;

Expressed as percent of total fatty acids;

Expressed as percent of total highly unsaturated fatty acids.

Comment

Our study did not support the hypothesis that EPA-rich fish oil or DHA-rich fish oil would prevent depressive symptoms in pregnant women at risk for depression. However, DHA levels did predict BDI score at 34–36 weeks. Strengths of our study are that it was carried out in a population of women at risk for depression; we chose to carry out our study among women with predisposition to depression so that our primary outcome would be sufficiently frequent. The blinded design of the trial was a strength; our analyses of side effects showed that the proportion of women who reported gastrointestinal side effects with the intervention did not differ between the groups, suggesting that the placebo intervention was appropriately masked. The comparison of fish oils that were high in either DHA or EPA was a strength as well. To our knowledge this is the first study to compare fish oils of these differing compositions among pregnant women.

A weakness of our study was that it had statistical power to detect differences in depressive symptoms but not in diagnoses of major depressive disorder. Adherence to the protocol in our study was not ideal; 14% of continuing subjects discontinued taking their capsules during their trial participation. The nonsignificant increases in DHA and EPA concentrations in the EPA-rich fish oil group compared with placebo suggest suboptimal compliance in the EPA group, although compliance measures did not differ according to group assignment. However, we found no evidence of benefit in the per-protocol analysis. This study may represent outcomes that might be encountered in actual clinical practice.

We found that serum DHA concentrations at 34–36 weeks significantly predicted BDI scores in late pregnancy but did not predict scores at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum. All groups experienced improvement in the BDI scores at 6–8 weeks’ postpartum, suggesting a possible placebo effect. The soy oil placebos used in this study contained a very small amount of fish oil for masking as well as a small amount of alpha linolenic acid, which may be endogenously converted to DHA and EPA, thus possibly serving as an active placebo. However, the DHA and EPA concentrations did not significantly increase over time in the placebo group, and available literature suggests that the endogenous conversion of linolenic acid to EPA and DHA is very low.26

Our findings are in agreement with those of Makrides et al,11 who found no benefit for DHA-rich fish oil for prevention of depressive symptoms among pregnant women who were not selected based on predisposition for depression. These findings are also compatible with those of Freeman et al,27 who found no additional benefit for EPA-predominant fish oil compared with interpersonal psychotherapy alone. Our findings do not agree with those of Su et al9 and earlier open-label studies by Freeman et al,7,8 which were suggestive of benefit. One possible reason that our results differed from those of Freeman and Su is that we tested lower doses of EPA and DHA than were used in those studies. However, Freeman’s dose-ranging trial found that higher doses of EPA plus DHA were not more effective than lower doses.8

Our trial was a prevention trial carried out among women who without a diagnosis of MDD at entry. It is possible that omega-3 fatty acids are effective for treatment rather than prevention of perinatal depression.

The prolongation of pregnancy noted in the DHA group is consistent with prior reports.11,28 Our study did not show an increased need for labor inductions in the supplemented group, but our sample size may have been insufficient to demonstrate such a difference.

In summary, we found no benefit for EPA-rich fish oil or DHA-rich fish oil supplementation to prevent depressive symptoms in pregnancy and postpartum. We demonstrated that maternal serum DHA concentrations at 34–36 weeks were significantly predictive of depression scores at the same time point. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanism underlying this relationship.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R21 AT004166-03S1 (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine) and a University of Michigan Clinical Research Initiatives grant and by the University of Michigan General Clinical Research Center, now the Michigan Clinical Research Unit. This study was also supported (in part) by the NIH through the University of Michigan’s Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA046592). This study was also supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, through grant 8UL1TR000041, for the Clinical and Translational Science Center, University of New Mexico. The Nordic Naturals Corporation donated both active supplements and placebos to the trial.

The Nordic Naturals Corporation donated both active supplements and placebos to the trial. The Nordic Naturals Corporation had no role in the interpretation or reporting of results. The Data Monitoring Committee included the following: Barbara Luke, ScD, Michigan State University; Charles Neal, MD, University of Hawaii; Mel Barclay, MD (deceased), University of Michigan; and Dwight Rouse, MD, Brown University. No funding or compensation was provided for service on the Data Monitoring Committee. Assistance for this study’s database construction was provided by Ms Michelle Housey, who was a student at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Her assistance to this study was funded by Dr Marjorie Treadwell’s University of Michigan Outstanding Clinician Award. Delia Vazquez, MD, University of Michigan Department of Pediatrics, assisted with the study design and enrollment infrastructure and had 1–2% effort on the R21 grant that supported this trial during 2 years of the trial period. The principal investigator would also like to acknowledge Ms Babett Riblett, RN; Ms. Mary Beaupre, LPN; Ms Joanne Wiklund, RN; Ms Lori Crimando, NP Joanne Bailey, CNM; Joyce Baker, CNM; and Mary McGuiness, CNM. All of those listed previously are employed by the University of Michigan and assisted with subject recruitment. Dr Jennifer Williams assisted with subject recruitment and data collection from the Integrated Health Associates/St Joseph Mercy Hospital site. None of these persons received any compensation or funding for their roles in this study.

Footnotes

E.L.M. was an invited speaker at the Nutracon 2012 Conference, sponsored by the Global Organization for EPA and DHA Omega-3s (GOED), Anaheim, CA, March 7–8, 2012, and received reimbursement for travel expenses.

The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Presented at the 33rd annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, San Francisco, CA, Feb. 11–16, 2013.

The racing flag logo above indicates that this article was rushed to press for the benefit of the scientific community.

Reprints not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Marcus SM. Depression during pregnancy: rates, risks and consequences—Motherisk Update 2008. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;16:e15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sie SD, Wennink JMB, van Driel JJ, et al. Maternal use of SSRIs, SNRIs and NaSSAs: practical recommendations during pregnancy and lactation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F472–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-214239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman MP, Rapaport MH. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: from cellular mechanisms to clinical care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:258–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11ac06830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibbeln J. Seafood consumption, the DHA content of mothers’ milk and prevalence rates of postpartum depression: a cross-national, ecological analysis. J Affect Disord. 2002;69:15–29. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golding J, Steer C, Emmett P, Davis JM, Hibbeln JR. High levels of depressive symptoms in pregnancy with low omega-3 fatty acid intake from fish. Epidemiology. 2009;20:598–603. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31819d6a57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larque E, Gil-Sanchez A, Prieto-Sanchez MT, Koletzko B. Omega 3 fatty acids, gestation and pregnancy outcomes. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(Suppl 2):S77–84. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512001481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman M, Hibbeln J, Wisner K, Watchman M, Gelenberg A. An open trial of omega-3 fatty acids for depression in pregnancy. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2006;18:21–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0924-2708.2006.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman M, Hibbeln J, Wisner K, Brumbach B, Watchman M, Gelenberg A. Randomized dose-ranging pilot trial of omega-3 fatty acids for postpartum depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006:31–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su KP, Huang SY, Chiu TH, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for major depressive disorder during pregnancy: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:644–51. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramakrishnan U, Stein AD, Parra-Cabrera S, et al. Effects of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation during pregnancy on gestational age and size at birth: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Mexico. Food Nutr Bull. 2010;31(Suppl 2):S108–16. doi: 10.1177/15648265100312S203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makrides M, Gibson RA, McPhee AJ, et al. Effect of DHA supplementation during pregnancy on maternal depression and neurodevelopment of young children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1675–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramakrishnan U. Fatty acid status and maternal mental health. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7(Suppl 2):99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins JG. EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28:525–42. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jans LA, Giltay EJ, Van der Does AJ. The efficacy of n-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA (fish oil) for perinatal depression. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1577–85. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, Mann JJ. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1577–84. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Yassini-Ardakani M, Karamati M, Shariati-Bafghi SE. Eicosapentaenoic acid versus docosahexaenoic acid in mild-to-moderate depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.08.003. published online ahead of print August 18, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mozurkewich E, Chilimigras J, Klemens C, et al. The mothers, omega-3 and mental health study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buist A, Condon J, Brooks J, et al. Acceptability of routine screening for perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2006;93:233–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holcomb W, Jr, Stone L, Lustman P, Gavard J, Mostello D. Screening for depression in pregnancy: characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:1021–5. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck CT, Gable RK. Comparative analysis of the performance of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale with two other depression instruments. Nurs Res. 2001;50:242–50. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn H, Blow F, Marcus S. Rates and predictors of depression treatment among pregnant women in hospital-affiliated obstetrics practices. Gen Hosp Pyschiatry. 2006;28:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steer R, Scholl T, Beck A. Revised Beck Depression Inventory scores of inner-city adolescents: pre- and postpartum. Psychol Rep. 1990;66:315–20. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.66.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcus S, Lopez J, McDonough S, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: impact on neuroendocrine and neonatal outcomes. Infant Behav Dev. 2011;34:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djuric Z, Ren J, Blythe J, VanLoon G, Sen A. A Mediterranean dietary intervention in healthy American women changes plasma carotenoids and fatty acids in distinct clusters. Nutr Res. 2009;29:156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson RA, Muhlhausler B, Makrides M. Conversion of linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid to long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), with a focus on pregnancy, lactation and the first 2 years of life. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7(Suppl 2):17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman MP, Davis M, Sinha P, Wisner KL, Hibbeln JR, Gelenberg AJ. Omega-3 fatty acids and supportive psychotherapy for perinatal depression: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makrides M, Duley L, Olsen SF. Marine oil, and other prostaglandin precursor, supplementation for pregnancy uncomplicated by pre-eclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction. Co-chrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003402. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]