Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effects of exenatide on body mass index (BMI) and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents with severe obesity.

Design

Three-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial followed by a three-month open label extension.

Setting

An academic medical center and an outpatient pediatric endocrinology clinic.

Patients

Twenty-six adolescents (age 12–19 years) with severe obesity (BMI ≥ 1.2 times the 95th percentile or ≥ 35 kg/m2).

Intervention

All patients received lifestyle modification counseling and were equally randomized to exenatide or placebo injection, twice per day.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary endpoint was the mean percent change in BMI measured at baseline and three-months. Secondary endpoints included absolute change in BMI, body weight, body fat, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and lipids at three-months.

Results

Twenty-two patients completed the trial. Exenatide elicited a greater reduction in percent change in BMI compared to placebo (−2.70%, 95% CI (−5.02, −0.37), P = 0.025). Similar findings were observed for absolute change in BMI (−1.13 kg/m2, 95% CI (−2.03, −0.24), P = 0.015) and body weight (−3.26 kg, 95% CI (−5.87, −0.66), P = 0.017). Although not reaching the level of statistical significance, reduction in systolic blood pressure was observed with exenatide. During the open label extension, BMI was further reduced in those initially randomized to exenatide (cumulative BMI reduction of 4%).

Conclusions

These results provide preliminary evidence supporting the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy for the treatment of severe obesity in adolescents.

Trial Registration

This study is registered on the www.clinicaltrials.gov website (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01237197).

Keywords: Exenatide, Obesity, Adolescents

Severe obesity afflicts approximately 4–6% of the United States pediatric population.1–4 Defined as an age- and gender-specific body mass index (BMI) ≥ 1.2 times the 95th percentile or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, severe obesity in childhood is associated with profound immediate and long-term consequences. Compared to overweight and obese children and adolescents, youth with severe obesity have a more adverse cardiometabolic risk factor profile and are at greatly elevated risk of developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus.2,5 Moreover, adiposity tracks particularly strongly from childhood to adulthood in the severely obese.2,6

Many adolescents with severe obesity achieve only marginal BMI reduction with lifestyle modification alone,7 and weight loss maintenance is often poor,8 highlighting the need for more aggressive and sustainable treatment strategies. While emerging data suggest that bariatric surgery is effective at reducing BMI and other cardiometabolic risk factors,9–11 significant risks accompany surgery and few pediatric patients are eligible due to lack of insurance coverage. Orlistat is the only FDA-approved weight loss medication for adolescents, but limited efficacy and notable side effects limit its widespread use.12 Therefore, new pharmacologic approaches are needed for the treatment of severe pediatric obesity.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, approved for use in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus, reduce body weight through enhancing satiety (slowing gastric motility) and suppressing appetite (activation of GLP-1 receptors in the hypothalamus), even in individuals without diabetes.13–15 Indeed, GLP-1 has been shown to be an endogenous satiety hormone.16 In a recent feasibility trial, we demonstrated that three-months of exenatide treatment reduced BMI by approximately 5% and improved markers of insulin resistance and β-cell function in adolescents with severe obesity who did not have diabetes.17 However, since the study included a small number of patients and was un-blinded, we performed a more rigorous evaluation of the effects of GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy in adolescents with severe obesity by conducting a randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. The primary endpoint was the mean percent change in BMI from baseline to three-months. Secondary endpoints included absolute change in BMI, body weight, body fat, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and lipids at three-months.

Methods

Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

This was a three-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial followed by a three-month open-label extension during which time active medication was offered to all patients. Although the study was primarily designed to evaluate outcomes at three-months, the open-label extension was included to provide further characterization of the safety profile, to better inform the design of future larger trials, and enhance recruitment by offering treatment to all patients. Adolescents ages 12–19 years old with severe obesity (BMI ≥ 1.2 times the 95th percentile or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) were recruited from the University of Minnesota, Amplatz Children’s Hospital Pediatric Weight Management Clinic (Minneapolis, MN) or the McNeely Pediatric Diabetes Center and Endocrinology Clinic, Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota (St. Paul, MN). Exclusion criteria included the following: diabetes mellitus (type 1 or 2), use of medications associated with weight loss/gain within three-months of screening, history of bariatric surgery, initiation of a new drug therapy within 30-days of screening, psychiatric disorders, current pregnancy/plans to become pregnant, current tobacco use, renal or liver dysfunction, history of pancreatitis, obesity-associated genetic disorders (e.g., Prader-Willi), hypothyroidism, uncontrolled hypertriglyceridemia (≥300 mg/dL), and history of an eating disorder.

Trained study coordinators delivered standardized lifestyle modification counseling to all patients throughout the entire trial. The lifestyle modification education materials were given to patients and selected sections were discussed at each monthly contact (five face-to-face sessions and two phone sessions). The curriculum was adapted from the NIDDK-sponsored “Take Charge of Your Health” and focused on encouraging patients to make healthier food choices and increase levels of physical activity. Pedometers and step-counting logs were given to all patients. Following baseline testing, patients were equally and randomly assigned to exenatide or matching placebo injection for three-months, followed by a three-month open label extension during which all patients received exenatide. The protocol was approved by the University of Minnesota and the Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota institutional review boards. Consent and assent were obtained from parents and patients, respectively. An investigational new drug exemption was obtained from the FDA prior to study initiation and the study was registered on the clinicaltrials.gov website (NCT01237197).

Exenatide and Placebo Dosing, Administration, and Tracking

Exenatide was initiated at a dose of 5 mcg, subcutaneously, twice per day (BID). After one-month, exenatide was up-titrated to 10 mcg BID for the remaining two-months of the randomized, placebo-controlled phase. In order to maintain the blind, the same titration protocol was used for the open label phase. Placebo pens were identical in appearance to the active medication pens. Compliance was assessed by medication logs and inspection of medication/placebo pens. The pre-determined threshold of compliance for inclusion in the per-protocol analysis was administration of ≥ 80% of the required doses.

Measurement of Clinical Variables

Clinical variables were obtained at baseline, three-, and six-months. Height and weight were obtained with patients in light clothes and without shoes using the same site-specific standardized stadiometer and electronic scale, respectively. Three consecutive height and weight measurements were averaged. Waist circumference was obtained (to the nearest 0.1 cm) at end-expiration midway between the base of the rib cage and the superior iliac crest. Three consecutive waist measurements were averaged. Percent total body- and visceral fat were determined using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (iDXA, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) at the University of Minnesota site only (N = 17). Seated blood pressure was obtained after five minutes of quiet rest, on the right arm using an automatic sphygmomanometer and appropriately-fitted cuff. The average of three independent blood pressure measurements was used. Tanner stage (pubertal development) determinations were performed by trained pediatricians. Fasting (≥12 hours) blood samples were analyzed for hemoglobin A1c, glucose, insulin, and lipids using standard procedures.

Statistical Analyses

The sample size was based primarily on the preliminary nature of the trial (a pilot study) along with limitations of the funding and recruitment timeline associated with the grant support. Baseline characteristics were tabulated with respect to randomized treatment regimens. Outcomes were evaluated at baseline, three-months (end of randomized treatment period), and six-months (end of open label extension). The primary endpoint was the mean percent change in BMI at three-months. Three-month treatment effects were estimated using generalized linear models to adjust for baseline measurements for added precision.18,19 Confidence intervals and P-values were evaluated based on a t-distribution and model-based standard errors. Robust variance estimation was not used due to small sample size. Due to incomplete follow-up on all patients who entered the study, the number of measurements for each treatment regimen was unbalanced. The primary analysis followed a pre-specified per-protocol analysis where patients were included if they completed the first treatment phase and missed no more than 20% of the prescribed exenatide doses. An intent-to-treat analysis was also conducted with missing three-month data imputed using the last available measurement (last observation carried forward). Data were housed in REDCap20 and all statistical analyses were performed using R v2.12.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

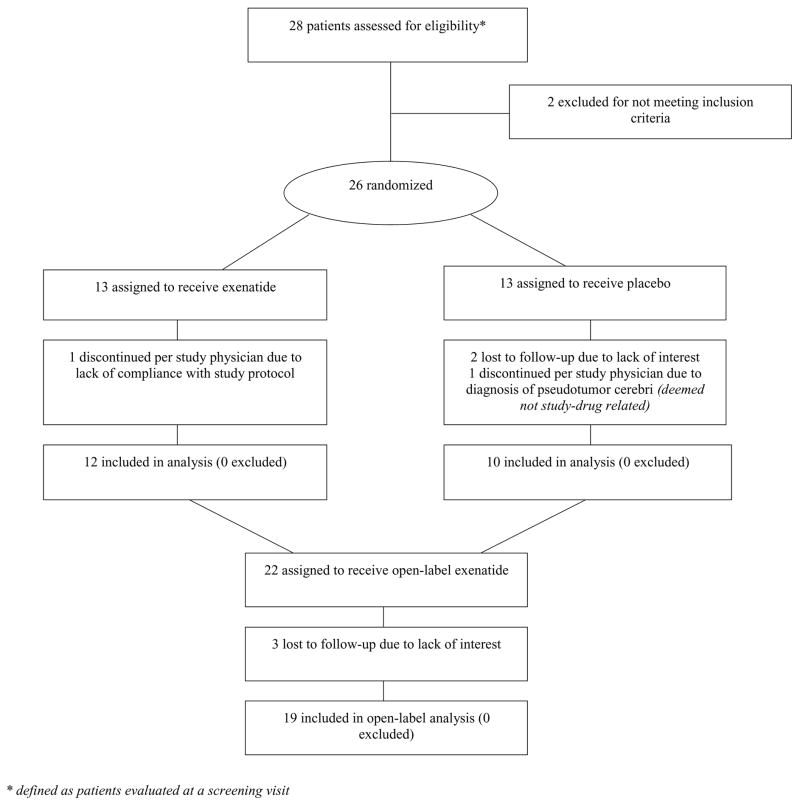

Enrollment occurred from January-November 2011. Figure 1 shows the progress of patients throughout the trial. Baseline characteristics of all randomized patients and of those who completed the trial are presented in Table 1. Four patients dropped out prior to three-month follow up (one from the exenatide group and three from the control group – reasons are shown in Figure 1). All 22 remaining patients achieved the target treatment dose and were compliant with the injection regimen during the first three-month phase (compliance ranged from 85–100% of the required doses; mean = 95%). Two participants required short-term (≤1-week) reduction to 5 mcg due to gastrointestinal symptoms but were then able to resume the 10 mcg dose without further problems for the remainder of the study. Data from one patient during the open label phase was excluded due to non-compliance (only data from the first three-month phase was used).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram showing the progress of patients throughout the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Randomized | Completed 3-mo Follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Covariate | Overall (N = 26) | Exenatide (N=13) | Placebo (N=13) | Exenatide (N=12) | Placebo (N = 10) |

| Age (years) | 15.2 (1.8) | 14.9 (1.76) | 15.5 (1.88) | 15.0 (1.82) | 15.3 (1.79) |

| Male (number) | 10 (38.5%) | 5 (38.5%) | 5 (38.5%) | 5 (41.7%) | 3 (30.0%) |

| Non-Hispanic (number) | 24 (92.3%) | 11 (84.6%) | 13 (100.0%) | 10 (83.3%) | 10 (100.0%) |

| Black (number) | 4 (15.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| White (number) | 20 (76.9%) | 10 (76.9%) | 10 (76.9%) | 10 (83.3%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| American Indian (number) | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other (number) | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Tanner Stage 3 (number) | 3 (11.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| Tanner Stage 4 (number) | 3 (11.5%) | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (7.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Tanner Stage 5 (number) | 20 (76.9%) | 11 (84.6%) | 9 (69.2%) | 10 (83.3%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 42.5 (6.81) | 42.3 (7.08) | 42.7 (6.81) | 40.8 (4.75) | 42.1 (6.67) |

| Weight (kg) | 124 (19.3) | 123 (18.1) | 126 (21.1) | 120 (15.4) | 121 (20.1) |

| Waist (cm) | 130 (14.1) | 130 (13.3) | 129 (15.5) | 128 (10.5) | 127 (14.4) |

| Total Tissue Fat (kg) | 61.1 (14.8) | 58.0 (14.4) | 64.6 (15.4) | 54.5 (10.3) | 61.6 (13.9) |

| Visceral Fat Area (cm2) | 1620 (511.3) | 1675 (671.0) | 1559 (273.3) | 1517 (507.1) | 1504 (243.0) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 122 (11.8) | 123 (11.2) | 120 (12.7) | 121 (9.49) | 120 (14.4) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 69.2 (8.83) | 71.2 (9.25) | 67.2 (8.27) | 71.2 (9.67) | 67.0 (9.39) |

| Heart Rate (BPM) | 76.8 (9.08) | 76.3 (8.05) | 77.4 (10.3) | 75.2 (7.4) | 77.9 (9.96) |

| Total-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 173 (31.4) | 161 (21.2) | 185 (35.9) | 160 (21.6) | 183 (32.0) |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 107 (27.3) | 97.4 (19.6) | 116 (31.4) | 94.8 (18.0) | 114 (23.2) |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 41.4 (6.95) | 39.9 (5.29) | 43.0 (8.21) | 40.2 (5.39) | 42.2 (9.19) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 126 (47.9) | 120 (51.0) | 132 (45.9) | 125 (50.0) | 132 (47.2) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 79.6 (11.1) | 79.2 (10.7) | 79.9 (12.0) | 79.5 (11.1) | 79.3 (9.87) |

| Insulin (mU/L) | 26.8 (19.6) | 31.5 (24.7) | 21.8 (10.8) | 30.6 (25.6) | 20.7 (10.7) |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.26 (0.28) | 5.23 (0.27) | 5.29 (0.3) | 5.23 (0.28) | 5.25 (0.31) |

Values presented are mean (standard deviation) or N (%) where indicated. To convert total-, LDL-, and HDL-cholesterol from mg/dL to mmol/L, multiply by 0.02586; for triglycerides, multiply by 0.01129; for glucose, multiply by 0.05551. To convert insulin from mU/L to pmol/L, multiply by 7.175.

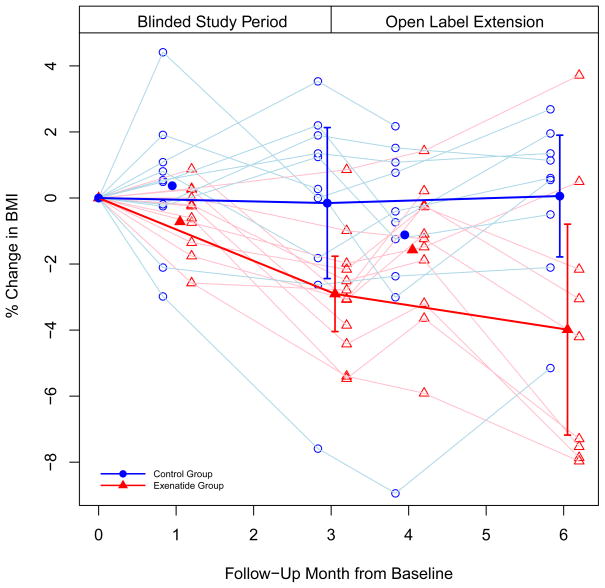

The change for each endpoint by group at three-months for those who completed the trial and the estimated treatment effects are presented in Table 2. At three-months, exenatide elicited a greater reduction in percent change in BMI compared to placebo (−2.70%, 95% CI (−5.02, −0.37), P = 0.025) (Figure 2). Similar findings were observed for absolute change in BMI (−1.13 kg/m2, 95% CI (−2.03, −0.24), P = 0.015) and body weight (−3.26 kg, 95% CI (−5.87, −0.66), P = 0.017). Treatment effect estimates stemming from the intent-to-treat analysis were not meaningfully different and the conclusions from the primary analysis remained unchanged for percent change in BMI (−2.72%, 95% CI (−4.68, −0.76)) and for absolute change in BMI (−1.14 kg/m2, 95% CI (−1.90, −0.38)) and body weight (−2.77 kg, 95% CI (−5.09, −0.44)). Although not reaching the level of statistical significance, clinically significant reduction in systolic blood pressure (SBP) was observed with exenatide compared to placebo.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary endpoints mean (SD) at three-months follow-up, change from baseline, and estimated treatment effect with 95% confidence interval.

| Covariate | N | Exenatide 3 mo. | Control 3 mo. | Exenatide Δ | Control Δ | Estimate (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change BMI | 22 | - | - | −2.90 (1.80) | −0.15 (3.20) | −2.70 (−5.02, −0.37) | 0.025 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22 | 39.64 (4.67) | 42.03 (6.95) | −1.18 (0.67) | −0.04 (1.23) | −1.13 (−2.03, −0.24) | 0.015 |

| Weight (kg) | 22 | 117 (14.85) | 122 (20.79) | −2.93 (2.48) | 0.32 (3.21) | −3.26 (−5.87, −0.66) | 0.017 |

| Waist (cm) | 22 | 126 (9.79) | 126 (13.45) | −2.04 (2.62) | −1.01 (5.57) | −0.98 (−4.60, 2.64) | 0.579 |

| Total Tissue Fat (kg) | 15 | 52.78 (9.50) | 60.95 (15.90) | −1.69 (2.41) | −0.65 (2.50) | −0.72 (−3.66, 2.23) | 0.606 |

| Visceral Fat Area (cm2) | 14 | 1420 (524.68) | 1548 (326.25) | −97.00 (191.22) | −18.17 (178.62) | −78 (−309, 153) | 0.473 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 22 | 116 (9.03) | 122 (7.90) | −5.50 (9.13) | 2.00 (13.43) | −6.36 (−13.46, 0.73) | 0.076 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 22 | 69.67 (5.42) | 66.50 (8.17) | −1.50 (9.76) | −0.50 (14.44) | 3.37 (−3.02, 9.76) | 0.283 |

| Heart Rate (BPM) | 22 | 77.25 (8.36) | 79.50 (8.95) | 2.00 (9.19) | 1.60 (11.96) | −1.57 (−9.34, 6.19) | 0.677 |

| Total-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 22 | 160 (19.36) | 176 (29.02) | 0.08 (13.01) | −6.60 (12.04) | 1.98 (−9.48, 13.44) | 0.722 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 21 | 91.91 (22.65) | 107 (19.17) | −1.45 (9.96) | −7.50 (17.64) | 1.52 (−12.81, 15.86) | 0.826 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 22 | 39.75 (5.61) | 39.20 (8.30) | −0.42 (4.08) | −3.00 (5.12) | 2.08 (−1.82, 5.99) | 0.278 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 22 | 128 (51.85) | 136 (48.98) | 2.83 (53.69) | 3.90 (44.41) | −4.71 (−45.14, 35.72) | 0.810 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 22 | 80.67 (9.76) | 83.90 (7.05) | 1.17 (8.19) | 4.60 (9.51) | −3.33 (−9.71, 3.05) | 0.288 |

| Insulin (mU/L) | 22 | 22.25 (13.07) | 22.80 (9.37) | −8.33 (18.81) | 0.67 (7.43) | −2.91 (−10.91, 5.10) | 0.455 |

| HbA1c (%) | 22 | 5.12 (0.26) | 5.24 (0.26) | −0.12 (0.16) | −0.01 (0.14) | −0.11 (−0.23, 0.01) | 0.072 |

To convert total-, LDL-, and HDL-cholesterol from mg/dL to mmol/L, multiply by 0.02586; for triglycerides, multiply by 0.01129; for glucose, multiply by 0.05551. To convert insulin from mU/L to pmol/L, multiply by 7.175.

Figure 2.

The percent change in BMI during the randomized, placebo-controlled phase and open label phase of the trial. Lighter lines denote individual trajectories (i.e., individual patients); darker lines denote group trajectories (mean percent change in BMI by group at three- and six-months, with 95% confidence bars).

After the open label extension, the average reduction in BMI from baseline for those initially randomized to exenatide was 4%. In those initially randomized to placebo who switched to exenatide, the average change in BMI from three-months to six-months was <0.25%.

The most common adverse events between baseline and three-months (all mild-moderate and transient) were nausea (placebo 31%, exenatide 62%), abdominal pain (placebo 23%, exenatide 15%), diarrhea (placebo 31%, exenatide 8%), headache (placebo 46%, exenatide 23%), and vomiting (placebo 8%, exenatide 31%). No subjects experienced hypoglycemia or pancreatitis.

Comment

Results of this clinical trial extend the findings of our previous pilot and feasibility study17 and offer additional evidence, within the context of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, that treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist significantly reduces BMI and body weight in adolescents with severe obesity. The percent BMI reduction achieved with exenatide in three-months (2.7%) was modest but the treatment effect was equivalent or better than three-months of treatment with orlistat12 or metformin,21 other medications that have been evaluated for their weight loss effects in youth.

Further reduction in BMI was observed during the open label phase in those initially randomized to exenatide (cumulative BMI reduction of 4%), suggesting that longer-term use may stimulate further BMI reduction as has been demonstrated in a trial of obese adults.14 It is interesting to note that the mean BMI rebounded slightly at month four in this group, which corresponded with the down-titration of exenatide, but subsequently decreased after the higher dose of exenatide was re-introduced (Figure 2). It is possible that had exenatide been maintained at the higher dose for the entire six-months, even greater BMI reduction may have been observed. It is unclear why BMI was not reduced during the open label phase in the group initially randomized to placebo. Perhaps, frustration with the lack of weight loss during the first three-months and/or the un-blinded nature of the open-label phase led to altered lifestyle behaviors for the remainder of the study.

Although not reaching the level of statistical significance, exenatide elicited a relatively large reduction on average in SBP (−6 mmHg), which is in line with our previous pediatric trial17 and with observations from adult studies.22 The mechanism(s) of SBP reduction with exenatide is currently unknown but only weak correlations have been observed with weight reduction in adults,22 suggesting other mechanisms in addition to weight loss may be responsible. The magnitude of SBP reduction with exenatide is relevant from a clinical perspective since blood pressure levels in youth with severe obesity, although often within the “normal” range, exceed levels observed in overweight and obese children and adolescents.23,24

Exenatide was generally well-tolerated. The reports of nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, and vomiting were transient and mild to moderate in severity and were consistent with reports from the adult literature. None of the patients in the current study discontinued participation due to gastrointestinal side effects and adherence to the twice daily injection regimen was excellent.

Other longer-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as exenatide extended-release (once weekly) and liraglutide (once daily), require less frequent dosing and may be more attractive to many adolescents and have a more sustained effect on GLP-1 receptors. The rebound in BMI observed with the downward titration of exenatide at month four in the current study suggests the possibility that higher-doses might elicit even greater weight loss, but this will need to be examined in subsequent studies.

The primary strength of this study was the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design. The sample size was relatively small and the treatment period was limited. Therefore, larger studies with longer periods of treatment will be needed in the future to evaluate the durability of the weight loss effect over time. Finally, the lifestyle modification counseling intervention used in the current study may not have been as comprehensive and/or intensive as what might be typically offered in a specialized pediatric weight management clinic setting. Therefore, the BMI reduction may have been greater if a multidisciplinary team of pediatric weight management specialists had been utilized.

In conclusion, data from the current study provide evidence that GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment reduces BMI and elicits a potentially meaningful reduction in SBP in adolescents with severe obesity. Compliance with the required injection regimen was excellent and exenatide was generally well-tolerated. Future clinical trials with GLP-1 receptor agonists should extend treatment beyond six-months and evaluate changes in other health outcomes such as non-invasive measures of arterial health, insulin sensitivity, and pancreatic β-cell function. In addition, subsequent studies should be designed to evaluate predictors of response to therapy in an attempt to better identify which obese adolescents are most likely to benefit from treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by a Community Health Collaborative Grant from the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute and from Award Number 1UL1RR033183 from the National Center for Research Resources and by Grant Number 8UL1TR000114-02 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, or the National Institutes of Health. Study drug and placebo were generously provided by Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. We would like to thank the patients and their families for donating their time to make this study possible. We are also grateful to Betsy Schwartz, M.D. (Park Nicollet) for providing independent oversight for data and safety monitoring, Charles Billington, M.D. (University of Minnesota) for consulting on study design and conduct issues, and Mary Deering, R.N. (University of Minnesota) for providing nursing support. Dr. Kelly had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: A.S.K. participated in study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafted the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; K.D.R. participated in study design, data interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; B.M.N. participated in study design, data collection, data interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; C.K.F. participated in study design, data interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; A.M.M. participated study design, data collection, data interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; B.J.C. participated in data analysis and interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; A.K.F. participated in data interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; E.M.B. participated in data interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published; M.J.A. participated in study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Disclosures: Dr. Kelly has received research funding from Amylin/Eli Lilly and served on a pediatric obesity advisory board (clinical trial design) for Novo Nordisk. Dr. Abuzzahab receives research funding from Amylin/Eli Lilly. None of the other authors have relevant disclosures.

Reference List

- 1.Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, Freedman DS, Johnson CL, Curtin LR. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index-for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1314–1320. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007;150:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koebnick C, Smith N, Coleman KJ, et al. Prevalence of extreme obesity in a multiethnic cohort of children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010;157:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skelton JA, Cook SR, Auinger P, Klein JD, Barlow SE. Prevalence and Trends of Severe Obesity Among US Children and Adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss R, Taksali SE, Tamborlane WV, Burgert TS, Savoye M, Caprio S. Predictors of changes in glucose tolerance status in obese youth. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:902–909. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304:2042–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston CA, Tyler C, Palcic JL, Stansberry SA, Gallagher MR, Foreyt JP. Smaller weight changes in standardized body mass index in response to treatment as weight classification increases. J Pediatr. 2011;158:624–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Arslanian SA, et al. Family-based treatment of severe pediatric obesity: randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1060–1068. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Qahtani AR. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in adolescent: safety and efficacy. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:894–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inge TH, Jenkins TM, Zeller M, et al. Baseline BMI is a strong predictor of Nadir BMI after adolescent gastric bypass. J Pediatr. 2010;156:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien PE, Sawyer SM, Laurie C, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in severely obese adolescents: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;303:519–526. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanoine JP, Hampl S, Jensen C, Boldrin M, Hauptman J. Effect of orlistat on weight and body composition in obese adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2873–2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dushay J, Gao C, Gopalakrishnan GS, et al. Short-term exenatide treatment leads to significant weight loss in a subset of obese women without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:4–11. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenstock J, Klaff LJ, Schwartz S, et al. Effects of exenatide and lifestyle modification on body weight and glucose tolerance in obese subjects with and without pre-diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1173–1175. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astrup A, Rossner S, Van GL, et al. Effects of liraglutide in the treatment of obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2009;374:1606–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:515–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly AS, Metzig AM, Rudser KD, et al. Exenatide as a weight-loss therapy in extreme pediatric obesity: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:364–370. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frison L, Pocock SJ. Repeated measures in clinical trials: analysis using mean summary statistics and its implications for design. Stat Med. 1992;11:1685–1704. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senn S. Change from baseline and analysis of covariance revisited. Stat Med. 2006;25:4334–4344. doi: 10.1002/sim.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metformin Extended Release Treatment of Adolescent Obesity: A 48-Week Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial With 48-Week Follow-up. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:116–123. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okerson T, Yan P, Stonehouse A, Brodows R. Effects of exenatide on systolic blood pressure in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:334–339. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly AS, Metzig AM, Schwarzenberg SJ, Norris AL, Fox CK, Steinberger J. Hyperleptinemia and hypoadiponectinemia in extreme pediatric obesity. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2012;10:123–127. doi: 10.1089/met.2011.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris AL, Steinberger J, Steffen LM, Metzig AM, Schwarzenberg SJ, Kelly AS. Circulating Oxidized LDL and Inflammation in Extreme Pediatric Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1415–1419. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]