Abstract

Here we report the engineering of zinc finger-like motifs containing the unnatural amino acid (UAA) (2,2′-bipyridin-5-yl)alanine (Bpy-ala). A phage display library was constructed in which five residues in the N-terminal finger of zif268 were randomized to include both canonical amino acids and Bpy. Panning of this library against a 9-base pair DNA binding site identified several Bpy-ala-containing functional zif268 mutants. These mutants bind the zif268 recognition site with affinities comparable to the wild-type protein. Further characterization indicated that the mutant fingers bind low spin Fe(II) rather than Zn(II). This work demonstrates that an expanded genetic code can lead to new metal ion binding polypeptides that may serve as novel structural, catalytic or regulatory elements in proteins.

Keywords: codon-expanded phage display, unnatural amino acid, zinc finger engineering, bipyridyl-Fe(II) complex

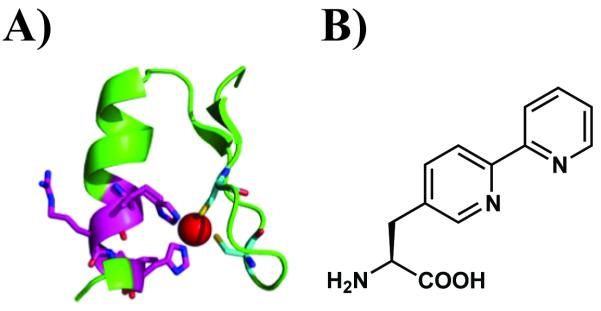

The structures of most proteins are derived from 20 canonical amino acid building blocks, together with posttranslational modifications and cofactors. In the past decade, we and others have successfully encoded unnatural amino acids (UAAs) with novel chemical and biological properties in response to nonsense or four-base codons in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms.[1] These UAAs can serve as useful probes of protein structure and function; moreover, recent work has demonstrated that these additional protein building blocks can endow proteins with new or enhanced functions.[2] In particular, metal ion binding amino acids might allow the generation of new structural, catalytic or regulatory motifs in proteins.[3] Here we report the evolution of a novel Zif268 zinc finger protein from a phage display library which in additional to the canonical twenty amino acids also encodes a bipyridyl amino acid (Bpy-ala, Fib. 1B). This mutant Zif268, which binds its target DNA with high affinity, has a finger domain that forms a bipyridyl·Fe(II) complex. These findings, together with a recent publication that describe a rationally designed Bpy-ala metal ion binding site, support the notion that functional metallo-proteins can be readily generated by introducing metal-chelating UAAs into proteins.[4]

Zinc fingers are common protein motifs in which one or more Zn(II) cations stabilize the protein fold. For example, the Zif268 zinc finger protein, a mammalian transcription factor, contains three zinc finger domains with (Cys)2(His)2 Zn(II) binding motifs.[5] The full-length protein selectively binds the dsDNA sequence 5′-GCG TGG GCG-3′, in which each 3 base-pair unit interacts with one finger domain. Previous experiments have shown that the finger domains are modular and can be modified to bind other DNA sequences or metal ions.[6] Each Zif268 finger motif adopts a β-β-α structure.[5a] In the N-terminal finger which selectively binds to the 3′ end of the recognition sequence (GCG), Zn(II) is coordinated by Cys7 and Cys12, located on each of the two β strands, and His25 and His29 on the α helix. (Figure 1A). Based on the structure of Zif268 N-terminal finger, we reasoned that the two monodentate imidazole groups of His25 and His29 of Zif268 might be replaced by a single bidentate bipyridyl group while preserving DNA binding.

Figure 1.

A) Structure of the N-terminal finger of Zif268. Residues 25-29 and the two cysteines are shown as sticks; the Zn(II) cation is shown as a red ball; B) Structure of (2,2′-bipyridin-5-yl)alanine (Bpy-ala).

To alter the metal ion binding site of the N-terminal zinc finger, we first created a Zif268 phage displayed library in which we randomized the two His residues and adjacent residues (His25, Ile26, Arg27, Ile28, and His29) of the N-terminal finger. While conventional phage display methods lack the capacity to incorporate unnatural building blocks, we have previously developed a codon-expanded phage display system, which allows the use of an expanded genetic code to display sequences with UAAs. This system was used to generate and pan libraries of antibody fragments containing UAAs for enhanced binding to target proteins[2c, 7] and cyclic peptides that can bind metal ions.[8] Here we adapted this codon-expanded phage display system to evolve zinc finger-like protein motifs that contain the unnatural amino acids, Bpy-ala.

We used overlap PCR to assemble randomized DNA fragments, which included NNK codons at residues 26, 27 and 28, and DNK codons at residues 25 and 29 (N = A, G, T or C; K = G or T; and D = A, G or T). The codon NNK encodes all 20 canonical amino acids, and in this system, the UAA in response to the amber stop codon (TAG). The codon DNK encodes 17 canonical amino acids (excluding His, Pro and Gln) and also the UAA in response to the TAG codon. This design ensures that the native Zif268 sequence is not included in the phage display library. Next, the assembled full-length Zif268 gene containing the N-terminal finger library was ligated into the pSEX81 phage display plasmid, upstream of the pIII gene of the filamentous M13 bacteriophage.[9] The library was cotransformed into E. coli Top10F′ cells with the pCDF-Bpy plasmid, which overexpresses an orthogonal tRNA/aaRS pairspecific for Bpy-ala[8]. The resulting transformed cells were infected by hyperphage and cultured in the presence of 1 mM Bpy-ala, producing Zif268 mutants displayed as pIII fusions at the surface of M13 in a polyvalent fashion. DNA sequencing showed that ~11% of phage contained a TAG codon in the randomized region, confirming that Bpy-ala had been integrated into the library. As a control, phage were also produced in the absence of Bpy-ala. Sequencing showed that less than 1% of phage from the latter library contained the TAG codon.

Selection experiments were carried out by mixing ~1×1010 phage with 40 nM biotin-labeled dsDNA containing the 5′-GCG TGG GCG-3′ binding sequence and 250 nM unlabeled competitive dsDNA containing the 5′-GCG TGG TAT-3′ sequence. Phage displaying Zif268 mutants whose N-terminal domain is properly folded and functional should bind the biotinylated DNA duplex with high affinity and be enriched. The mixture was loaded to a streptavidin-coated well of a 96-well plate. Nonspecifically bound phage were removed by repetitive washes. Remaining phage were eluted with DNase I, and used to infect Top10F′ cells harboring the tRNA/aaRS genes encoding Bpy-ala. Five rounds of selection enriched phage that specifically bound to the target dsDNA, as evidenced by a decrease of the phage input/output ratio from ~ 105 to ~ 102. Phagemids were then sequenced and analysis of the results revealed three different TAG-containing sequences that each appeared multiple times. The corresponding protein sequences are shown in Table 1. All mutants contain one Bpy-ala and no histidine.

Table 1.

Protein sequences of Zif268 and its engineered mutants.

| Residues | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | Kd[a] (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zif268 | His | Ile | Arg | Ile | His | 5.2±3.0 |

| Mut1 | Glu | Asn | Gly | Val | Bpy | 11.5±4.1 |

| Mut2 | Arg | Thr | Ser | Bpy | Glu | 9.0±4.6 |

| Mut3 | Gly | Bpy | Thr | Met | Gly | 11.3±5.3 |

Apparent dissociation constants were determined by EMSA. Values are an average of three independent experiments with standard deviations.

To test whether Bpy-ala is required for DNA binding by the mutant proteins, the selected phagemids were introduced into Top10F′ cells harboring either the pCDF-Bpy plasmid or a similar pCDF-Tyr plasmid expressing a tRNA/aaRS pair that suppresses TAG with tyrosine. These phage displayed mutant zinc fingers have either Bpy-ala or Tyr encoded by TAG. Both groups of phage were directly panned against the target dsDNA in the presence of competitive dsDNA; bound phage were eluted and phage input/output ratios were calculated. A significantly higher percentage of Bpy-ala-containing phage were bound to the target DNA, suggesting that Bpy-ala is essential for DNA binding (Supporting Information (SI) Figure S1).

We characterized the DNA binding affinity of the mutants using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). The full-length wt and three mutant Zif268 sequences were inserted into a pBAD plasmid containing a N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP) tag, and affinity purified from E. coli as soluble MBP fusions. The mutants and wt MBP-Zif268 proteins were incubated with 0.5 nM 3′-biotin-labeled target dsDNA, electrophoresed on a 4-20% TBE polyacrylamide gel and detected with a Streptavidin-HRP conjugate. The apparent dissociation constants (Kd) were estimated by titration of different concentrations of proteins. (Figure S2). The Kd’s of these mutants are comparable to the Kd of the wild-type Zif268 (Table 1), indicating that Bpy-ala-contaning Zif268 mutants maintain their DNA binding activity. Adding biotin-labeled competitive dsDNA (containing a 5′-GCGTGGTAT-3′ binding site) to the MBP-Zif268 mutants had no effect on gel mobility (Figure S3), suggesting that the mutants also retain their sequence specificity.

Next we mutated the potential metal ion binding residues of Mutant 1 to determine whether they play a role in the structure and function of the mutant zinc finger protein. Substitution of the bipyridyl side chain with a biphenyl group (Figure S4A, expressed using an orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pair specific for biphenylalanine)[3a] resulted in a complete loss in DNA binding as determined by EMSA (Figure S4B). In contrast, mutants in which either Cys7 or Cys12 were subsitituted with Ser, or in which Glu25 was subsitituted with Gln bound DNA with reduced affinity, suggesting that these residues affect protein folding.[10] (Figure S4C-F). The presence of EDTA (100 μM), resulted in a loss of DNA binding affinity (Figure S4G). These results demonstrate that metal coordination by the bipyridyl moiety is required for DNA binding and plays a key role in the function of the mutant Zif268 protein.

In contrast to the wild-type and biphenyl-containing mutant MBP-Zif268 fusion proteins, all Bpy-ala containing mutant proteins were slightly red in color, suggesting that they may form distinct metal ion complexes.[11] To determine the identity of the metal ion in the N-terminal finger, we fused the gene encoding the N-terminal finger region of each mutant Zif268 protein to the 5′ end of a T4 lysozyme (T4L) gene (T4L is a low molecular weight protein known to be highly expressed in E. coli).[12] These sequences were then inserted into pET28a expression plasmid and expressed as 6×His fusion proteins in E. coli. The resulting purified Zif268-T4L fusion proteins were also red in solution. Each protein contains one mutant zinc finger and a T4L domain. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was used to characterize these proteins (Figure S5). In addition to peaks corresponding to the molecualr weight of the Bpy-ala-containing protein sequences, additional peaks that correspond to iron-bound proteins were also observed, suggesting that the Bpy-ala containing mutants formed an iron-dependent finger like strucutre. It is likely that the mutant proteins bind iron present in the cytoplasm or media given the high kinetic and thermodynamic stability of bipyridyl-iron complexes[5a, 13] (attempts to alter the metal ion content of the growth media or buffers did not afford a Zn2+ bound mutant).

To further investigate this polypeptide-metal ion complex, we determined the UV-Vis absorption spectra of the T4L fusion proteins (Figure S6A). Whereas the wild-type Zif268-T4L fusion protein is largely featureless between 357 nm and 900 nm, all three mutants show several bands in this spectral region. In particular, a prominent feature was observed at ~ 526 nm. Fe(II) bipyridine (bipy) and related diimine complexes tend to have an Fe(II) dπ orbital to bipy π* orbital metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transition in this energy region, whereas Fe(III) diimine complexes have an MLCT at ~ 385 nm[14] The circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of the Mut1-T4L fusion (Figure S6B) showed that this 526 nm feature is actually comprised of two transitions which may be derived from the dπ orbitals to bipy π* orbitals close in energy, indicating bidentate binding.[15] Addition of sodium dithionite under anaerobic conditions did not change the spectrum. Together, these data appear to indicate that our engineered mutants are complexed with Fe(II) as opposed to Fe(III) with the bipy moiety coordinated in a bidentate fashion. Attempts to remove the Fe(II) with EDTA and refold the protein in the presence of Zn(II) or Ni(II) were unsuccessful.

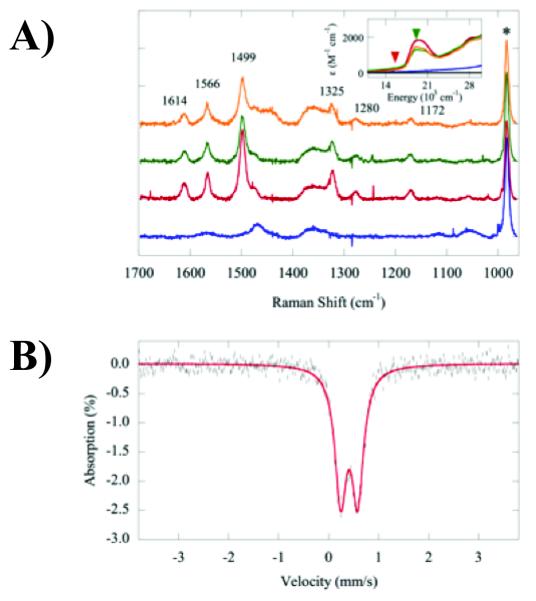

We next examined the protein electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra, along with a control Fe(III)-EDTA sample at the same concentration at 4.2 K (Figure S7). EPR features at g ≈ 4.3 are typical for high-spin Fe(III) in a rhombic (i.e. low symmetry) environment. From integration of the spectra, the high-spin Fe(III) present in each protein sample is less than 3%. Also, no features for low-spin Fe(III) (g ≈ 2) were found. This result also supports the notion that virtually all iron in the protein samples is Fe(II). Resonance Raman spectra were also collected at 531 nm (18800 cm1) (Figure 2a). Fusion proteins of mutant fingers showed features at 1172, 1280, 1325, 1499, 1566 and 1614 cm−1, which were absent for the wild-type Zif268 fusion (blue spectrum). These features were not present in spectra collected using 647-nm excitation (Figure S8) and are therefore resonance-enhanced. It is worth noting that these transitions are close to those previously observed for [Fe(II)(bipy)(CN)4]2− (peaks at ~ 1175, 1275, 1320, 1490, 1555 and 1605 cm−1) and correspond to bipy ring vibrational modes resonance-enhanced by excitation into the MLCT.[16] These data further corroborate that Fe(II) cations in our mutant fingers are coordinated by the bipyridyl group. Finally, an 57Fe-enriched Mut1-T4L fusion protein was expressed by culturing E. coli in M9 minimal media supplemented with 100 μM 57FeCl , and the 57 2 Fe Mössbauer spectrum of the purified protein was collected at 4.2 K (Figure 2b). The data could be fit with a single quadrupole doublet with an isomer shift δ = +0.41 mm/s and quadrupole splitting ΔEq = 0.34 mm/s. High-spin Fe(II) complexes tend to possess δ’s of +0.6 to +1.7 mm/s and ΔEq’s > 1.0 mm/s, whereas low-spin Fe(II) complexes possess δ’s of −0.2 to +0.5 mm/s and ΔEq’s < 1.0 mm/s.[17] Magnetic circular dichroism spectra were taken and did not show any temperature-dependent features (Figure S9). Moreover, CD spectra of Mut1 taken at room temperature and at 5 K (Figure S6B) match each other well. Taken together, the above experiments showed that the coordinated Fe is in a low-spin ferrous state at both low and room temperatures. Because the Bpy-ala Zif268 mutants bind DNA with comparable affinity and selectivity to wt protein, we speculate taht low-spin Fe (II) promotes an overall fold similar to that of the wt protein. While the exact nature of the Fe(II) coordination sphere is still unclear, it is presumably 5- or 6-coordinate rather than 4-coordinate as is found in the Zn(II) proteins as a tetrahedral ligand field would be too weak for low-spin Fe(II). We are attempting to crystallize the protein to determine the structure of the Fe(II) coordination site.

Figure 2.

A) Resonance Raman spectra collected at 531 nm (18800 cm−1) for T4L fusion proteins (0.5 mM) containing the N-terminal fingers of Zif268 (blue), Mut1 (red), Mut2 (green) or Mut3 (orange) in 50 mM Tris (pH 8) containing 100 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol. Resonance-enhanced peaks are labeled with their Raman shifts. The feature marked by an asterisk is from sodium sulfate added to the samples as an internal standard. In the inset are the absorption spectra (in colors corresponding to those in the Raman plot) showing Raman collection at 647 nm (red triangle) and 531 nm (green triangle); B) 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum (black lines) of the Mut1-T4L fusion (3.8 mM) and its best fit (red line).

In summary, we have evolved several mutant Zif268 N-terminal fingers that use bipyridyl for proper folding and function. These mutant fingers can coordinate low-spin Fe(II) to stabilize their folds, and retain their affinity for their operator DNA sequence. It should be possible to use similar in vitro evolution methods to generate other metal ion-dependent activities with catalytic, redox-active and regulatory functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by DE-FG03-00ER46051 from The Division of Materials Sciences, DOE (P.G.S.) and the NIH Grant GM 40392 (E.I.S.). This is manuscript #21952 of The Scripps Research Institute. We thank Virginia Seely for manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Experimental Section

See the supporting information.

Supporting information for this article is available.

References

- [1].a) Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz PG. Science. 2001;292:498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu CC, Schultz PG. Annual review of biochemistry. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Seyedsayamdost MR, Xie J, Chan CT, Schultz PG, Stubbe J. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:15060–15071. doi: 10.1021/ja076043y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Grunewald J, Tsao ML, Perera R, Dong L, Niessen F, Wen BG, Kubitz DM, Smider VV, Ruf W, Nasoff M, Lerner RA, Schultz PG. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:11276–11280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804157105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liu CC, Mack AV, Tsao ML, Mills JH, Lee HS, Choe H, Farzan M, Schultz PG, Smider VV. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:17688–17693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809543105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Young TS, Young DD, Ahmad I, Louis JM, Benkovic SJ, Schultz PG. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11052–11056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108045108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kim CH, Axup JY, Dubrovska A, Kazane SA, Hutchins BA, Wold ED, Smider VV, Schultz PG. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134:9918–9921. doi: 10.1021/ja303904e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Xie J, Liu W, Schultz PG. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:9239–9242. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee HS, Schultz PG. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:13194–13195. doi: 10.1021/ja804653f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lee HS, Spraggon G, Schultz PG, Wang F. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:2481–2483. doi: 10.1021/ja808340b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Maini R, Nguyen DT, Chen SX, Dedkova LM, Chowdhury SR, Alcala-Torano R, Hecht SM. Bioorgan Med Chem. 2013;21:1088–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mills JH, Khare SD, Bolduc JM, Forouhar F, Mulligan VK, Lew S, Seetharaman J, Tong L, Stoddard BL, Baker D. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:13393–13399. doi: 10.1021/ja403503m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Pavletich NP, Pabo CO. Science. 1991;252:809–817. doi: 10.1126/science.2028256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fairall L, Schwabe JW, Chapman L, Finch JT, Rhodes D. Nature. 1993;366:483–487. doi: 10.1038/366483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Lu Y, Yeung N, Sieracki N, Marshall NM. Nature. 2009;460:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nature08304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Krizek BA, Merkle DL, Berg JM. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:937–940. [Google Scholar]; c) Struthers MD, Cheng RP, Imperiali B. Science. 1996;271:342–345. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Wu H, Yang WP, Barbas CF., 3rd Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:344–348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Green A, Sarkar B. The Biochemical journal. 1998;333(Pt 1):85–90. doi: 10.1042/bj3330085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Bulyk ML, Huang X, Choo Y, Church GM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:7158–7163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111163698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu CC, Mack AV, Brustad EM, Mills JH, Groff D, Smider VV, Schultz PG. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:9616–9617. doi: 10.1021/ja902985e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Day JW, Kim CH, Smider VV, Schultz PG. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2013;23:2598–2600. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rondot S, Koch J, Breitling F, Dubel S. Nature biotechnology. 2001;19:75–78. doi: 10.1038/83567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Elrod-Erickson M, Benson TE, Pabo CO. Structure. 1998;6:451–464. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lieberman M, Sasaki T. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113:1470–1471. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rose DR, Phipps J, Michniewicz J, Birnbaum GI, Ahmed FR, Muir A, Anderson WF, Narang S. Protein engineering. 1988;2:277–282. doi: 10.1093/protein/2.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ghadiri MR, Soares C, Choi C. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114:825–831. [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Schilt AA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1960;82:3000–3005. [Google Scholar]; b) Bryant GM, Fergusso Je, Powell HKJ. Aust J Chem. 1971;24:257–&. [Google Scholar]; c) Krumholz P, Serra OA, Depaoli MA. Inorg Chim Acta. 1975;15:25–32. [Google Scholar]; d) Amani V, Safari N, Khavasi HR. Polyhedron. 2007;26:4257–4262. [Google Scholar]; e) Amani V, Safari N, Khavasi HR, Mirzaei P. Polyhedron. 2007;26:4908–4914. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gondo Y. J Chem Phys. 1964;41:3928. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Miller PJ, Chao RSL. J Raman Spectrosc. 1979;8:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Parish RV, Parish RV. Mössbauer spectroscopy and the chemical bond Mössbauer spectroscopy. Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]; b) Drago RS. Physical methods for chemists. Saunders College Pub.; 1992. [Google Scholar]; c) Reiff WM, Dockum B, Weber MA, Frankel RB. Inorg Chem. 1975;14:800–806. [Google Scholar]; d) Sato H, Tominaga T. B Chem Soc Jpn. 1976;49:697–700. [Google Scholar]; e) Morigaki MK, da Silva EM, de Melo CVP, Pavan JR, Silva RC, Biondo A, Freitas JCC, Dias GHM. Quim Nova. 2009;32:1812–U1150. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.