Abstract

This study explores the relationship between clinician-reported content addressed in sessions, measured with the Session Report Form (SRF), and multi-informant problem alerts stemming from a larger battery of treatment process and progress measures. Multilevel multinomial logit models were conducted with 133 clinicians and 299 youths receiving home-based treatment (n = 3,143 sessions). Results indicate a strong relationship between session content and problems related to youth symptoms and functioning as reported by clinicians in the same session. Session content was related to emotional, family, and friend/peer problems reported by youth and youth behavioral problems reported by caregivers. High-risk problems (alcohol/substance use, harm to self or others) were strongly related to session content regardless of informant. Session content was not related to problem alerts associated with the treatment process, caregiver strain, or client/caregiver strengths. The SRF appears to be a useful measure for assessing common themes addressed in routine mental health settings.

Keywords: youth, caregiver, clinician, Session Report Form, treatment as usual, describing practice, respondent differences

Over the past several years, researchers have increased attention to measuring what happens within the therapeutic encounter in usual care settings. Efforts to reform youth mental health care in community settings will continue to fall short without an explicit focus on the clinician as a key mechanism of change in the therapeutic process (Bickman, 2008; Garland, Bickman, & Chorpita, 2008; Kazdin, 2008; Sexton & Kelley, 2010). Several promising approaches to measuring clinician behavior in sessions have been identified along with criteria for assessing their utility (see reviews by Burnam, Hepner, & Miranda, 2009; Kelley, Vides de Andrade, Sheffer, & Bickman, 2010; Miranda, Azocar, & Burnam, 2010; Schoenwald et al., 2011). Measures vary based on methodology (e.g., observational, interview, and survey measures), scope (e.g., model-specific strategies, therapeutic orientations, and general practice behavior), and timing of administration (e.g., one-time summaries to session-based). There can be multiple purposes for using these instruments beyond monitoring implementation fidelity for evidence-based treatment research. Regular use in routine care can contribute to gathering data for reporting accountability to funders, planning workforce development for clinicians, and guiding treatment for individual clients (Miranda et al., 2010; Schoenwald et al., 2011).

To enhance feasibility of use in routine care, measures must be brief, psychometrically sound, and clinically useful (Kelley & Bickman, 2009). Observational measures such as the Therapy Process Observational Coding System for Child Psychotherapy Strategies Scale (TPOCS-S; McLeod & Weisz, 2010) are ideal for providing objective assessments of clinician behavior and verbal interactions in sessions. Increased availability of technology for uploading video easily and securely for review (e.g., webcams and cloud storage) makes regular use of observational methods more feasible (Schoenwald et al., 2011). Given the time needed for coding, observational methods are best suited for treatment research and workforce development (e.g., clinician coaching or supervision).

If the purpose of measurement is to inform treatment for individual clients, survey methods can be easily administered and scored for immediate use during concurrent treatment. While client- and clinician-report measures may have limited use for objective accuracy, they do give insight into individual perspectives such as a clinician's intent of practice or a client's awareness and understanding of the therapeutic experience (Burnam et al., 2009). There are several promising examples of client- and clinician-report measures with evidence of validity and reliability as well as feasibility in routine settings (see reviews by Burnam et al., 2009; Kelley et al., 2010; Miranda et al., 2010; Schoenwald et al., 2011).

One such measure, the Session Report Form (SRF; Kelley, et al., 2010), is a clinician-report measure of therapeutic content addressed in sessions, a global aspect of clinician behavior within the therapeutic encounter. Psychometric properties include good internal consistency, with some evidence for a distinct subscale of treatment process. There is also evidence of content validity, with an adequate range of topics related to session content and the ability to discriminate between client and clinician influences on patterns of topics addressed. The SRF does not require clinicians to report on specific therapeutic strategies (e.g., relaxation training) or orientations (e.g., cognitive-behavioral), which has been shown to be unreliable and difficult to do without training (Hurlburt, Garland, Nguyen, & Brookman-Frazee, 2010). Rather, the content domains assessed cover the common issues relevant to youth psychotherapy including symptoms and functioning (e.g., emotional, behavioral, friends/peers), caregiver functioning, and the treatment process itself (e.g., motivation for treatment, therapeutic relationship). In contrast to other measures given on a less frequent basis such as the Monthly Treatment and Progress Summary (MTPS; Nakamura et al., 2007) or the Therapy Procedures Checklist (TPC; Weersing et al., 2002), the SRF is a brief form intended to be completed as part of regular session documentation (e.g., a progress note).

While previous research supports the feasibility of the SRF for assessing clinician behavior in routine care settings (Kelley et al., 2010) it is as yet unknown how information on session-based content addressed or treated as an important focus can be used to inform practice. When the focus is adherence to evidence-based treatment models or elements, measures of clinician behavior can be used in clinical decision-making to understand whether adherence to the model may be a source of client improvement or deterioration (Schoenwald et al., 2011). However, with non-specific practice behavior such as the content addressed in sessions, the most relevant metric for clinical usefulness may be whether or not the clinician is addressing issues of importance to clients. At a minimum, it is generally accepted that good clinical practice entails assessing problems at the outset of treatment and addressing those problems or new ones that arise during the course of youth mental health treatment (e.g., Hawley & Weisz, 2003; Weisz et al., 2011).

Ongoing assessment of problems is vital not only to establishing a treatment plan and building a working alliance, but also to assessing treatment progress. When asked, clinicians state that they make treatment decisions based on worsening of client symptoms (Hatfield, McCullough, Frantz, & Krieger, 2010). However, clients may operationalize desirable outcomes or identify target problems differently. Adult clients in treatment for depression reported that positive features of mental health, such as optimism and self-confidence, were better indicators of treatment outcome than symptom resolution (Zimmerman et al., 2006). Hawley and Weisz (2003) found that over three quarters of youth-caregiver-clinician triads did not agree on a single problem for youth beginning treatment at community mental health centers. In addition, clinicians’ reports of treatment progress exhibit low correspondence with standardized measures completed by youths or caregivers (e.g., Love, Koob, & Hill, 2007) or adult clients (Hannan et al., 2005; Hatfield et al., 2010). Posttreatment global improvement in social functioning for youths diagnosed with social phobia was more associated with caregiver reports than with those of youths (De Los Reyes, Alfano, & Beidel, 2011).

Rather than focusing on agreement on youth problems or treatment progress, this study examines how problems reported by the primary participants in the treatment process are related to therapeutic content in each session. A unique benefit of the SRF is that it was explicitly developed to correspond to youth-related concerns reported by multiple informants. When administered as part of a larger battery of treatment progress and process measures administered at each session (Bickman et al., 2010), it is possible to examine the relationships between what clinicians report addressing in a session and the current perceived problems reported by clinicians, youths, and caregivers. This allows a session-by-session examination of how the content that clinicians say they address or treat as an important focus is related to current problems reported by all the key stakeholders in treatment.

The current study has two primary aims. The first aim is to build on previous research (Kelley et al., 2010) by examining the convergent validity of the SRF to further support its utility in routine care settings. Thus, it was hypothesized that clinicians’ report of content addressed or an important focus of sessions would be positively correlated with their own report of problems related to treatment progress (e.g., youth symptoms and functioning) completed at the same time. The second aim is to examine how clinician-reported session content is associated with client- and caregiver-reports of treatment progress and treatment process (e.g., motivation for treatment, therapeutic relationship). To our knowledge this study is the first to report on the relationship between clinician-reported session content and youth-related problems reported by others throughout treatment. Thus, we based our hypotheses on related research that describes multi-informant agreement on target problems at intake with similarly aged youth treated in community settings (e.g., Hawley & Weisz, 2003). We hypothesized that clinicians’ report of session content will be associated (a) to a lesser extent with problems reported by others compared to their own report, (b) to a lesser extent with problems reported by youths compared to caregivers, and (c) differently by problem type and informant. Specifically, we expect that family and environmental (e.g., school/work and friends/peers) problems reported by youths will be more highly correlated with session content than that of caregivers, whereas the opposite would be true for behavioral and emotional problems.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study represent a sub-sample drawn from a larger longitudinal cluster randomized experiment evaluating the effects of a measurement feedback system (CFS; Contextualized Feedback Systemstm) on mental health outcomes for youth receiving ‘treatment as usual’ from a national provider of home-based mental health services (Bickman et al., 2011). Typical services included individual and family in-home counseling, intensive home-based services, crisis intervention, substance abuse treatment, life skills training, and case management. Common client presenting problems encompassed a wide variety of issues including school problems, mood and anxiety disorders, oppositional behavior, and impulsivity/attention deficit disorders.

To be included here, youth from the larger evaluation sample had to have at least one session where the clinician completed the SRF measure. A total of 133 clinicians completed SRFs for 3,143 sessions for 299 youths aged 11 to 18 years (Mean = 14.8, SD = 1.8). This subsample represented 92% of all clinicians, 83% of all sessions, and 88% of all clients from the larger study. Approximately half (51%) of youths were male and 57% were Caucasian, with the remaining youths identified as African American (23%) or other. In addition, 13% of youths identified themselves as Hispanic. All youths were new clients receiving home-based counseling.

The typical caregiver was 43.4 years old (SD = 10.4, ranged from 23 to 77 years), female (86%), Caucasian (68%), non-Hispanic (94%), and married (40%). Slightly over half (60%) reported they had a high school diploma and 71% made less than $35,000 per year (46% made less than $20,000). Over half (66%) were biological parents, 28% were other relatives (e.g., grandparents), and 6% were non-biologically related foster parents.

The typical clinician was female (80%), Caucasian (66%), non-Hispanic (94%) and 36.6 years of age (SD = 10.2, ranged from 22 to 68 years). Each clinician had three CFS clients on average (SD = 2.8), ranging from one to 18 clients. The majority (74%) of clinicians had a master's degree. About a third (32%) were social workers, 36% were clinicians or pastoral clinicians, and 16% were psychologists, with those remaining reporting other unspecified educational backgrounds. A subsample of clinicians (N=50) who reported on their years of experience had worked at the current clinic for about two years (SD=0.7, range= 0 to 4 years), with about four years of experience in the field (SD=1.5, range=1 to 7 years). The Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University approved all study procedures.

Measures

The Session Report Form (SRF; Kelley et al., 2010) is a 25-item self-report measure developed collaboratively by a team of clinicians and researchers and designed for use in any type of treatment. Clinicians complete the SRF as part of the documentation associated with a specific treatment session (e.g., progress notes). As such, the SRF is intended to be completed at the end of each session and takes an estimated two to three minutes to complete. In addition to items describing session characteristics (i.e., who participated, length and location of the session, rating of the session, and time spent in crisis) the SRF contains 20 content domains that assess common themes addressed in youth mental health care. For each content domain (e.g., emotional issues, family issues) the clinician responded on a Likert-type scale ranging from (0) whether the topic was not addressed, (1) addressed, or (2) addressed and an important focus of the session. No additional information was provided on how to complete the measure. The Cronbach's coefficient alpha for internal consistency was 0.79 for the set of 20 content domains (Kelley et al., 2010). A principal component analysis indicated the presence of a distinct subscale for 10 of the items with a Cronbach's coefficient alpha of 0.81. Named the SRF Treatment Process Index, the set of 10 items corresponds to common factors of treatment such as motivation for treatment and therapeutic alliance (in Table 1 below these are the last 10 items).

Table 1.

PTPB Measure Sources of Session Problem Alerts by SRF Topic and Informant

| SRF Topic | Informant1 | Measure3 | Administration Schedule | # Problem Alert Items3 | Likert Scale for Items3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional issues | Y, Cg, Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 13 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Behavioral issues | Y, Cg, Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 16 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Family issues | Y, Cg, Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 4 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| School/work issues | Y, Cg, Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 3 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Friends/peer issues | Y, Cg, Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 6 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Problems w/delinquent behavior | Y, Cg, Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 3 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Alcohol/substance use | Y, Cg, Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 2 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Harm to self or others | Cl | SFSS | Even weeks | 1 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Client hope for future | Y | CHS-PTPB | Once/quarter | 4 | 1 – 6 (low) |

| Client motivation for treatment | Y | MYTS | Twice/quarter | 4 | 1 – 5 (low) |

| Therapeutic relationship w/client | Y | TAQS | Odd weeks | 5 | 1 – 5 (low) |

| Client perceptions on counseling impact | Y | YCIS | Odd weeks | 6 | 1 – 5 (low) |

| Client satisfaction w/services | Y | SSS | Once/quarter | 4 | 1 – 4 (low) |

| Caregiver strain | Cg | CGSQ-SF7 | Once/quarter | 7 | 1 – 5 (high) |

| Caregiver satisfaction w/life | Cg | SWLS | Twice/quarter | 5 | 1 – 7 (low) |

| Caregiver motivation for youth treatment | Cg | MYTS | Twice/quarter | 7 | 1 – 5 (low) |

| Therapeutic relationship w/caregiver | Cg | TAQS | Odd weeks | 5 | 1 – 5 (low) |

| Caregiver satisfaction w/services | Cg | SSS | Once/quarter | 4 | 1 – 4 (low) |

Note: Y=Youth; Cg=Caregiver; Cl=Clinician.

Note: SFSS= Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale (Athay, Riemer, & Bickman, 2012); CHS-PTPB = Children's Hope Questionnaire-Revised PTPB edition (Dew-Reeves, Athay, & Kelley, 2012); MYTS=Motivation for Youth's Treatment Scale (Breda & Riemer, 2012); TAQS=Therapeutic Alliance Quality Scale (Bickman, Vides de Andrade, Athay, Chen, DeNadai, Jordan-Arthur, & Karver, 2012); YCIS=Youth Counseling Impact Scale (Kearns & Athay, 2012); SSS=Service Satisfaction Scale (Athay & Bickman, 2012); CGSQ=Caregiver Strain Questionnaire-SF7 (Brannan, Athay, & Vides de Andrade, 2012); SWLS=Satisfaction with Life Scale (Athay, 2012).

Problem alert are items rated at the top 25% of the distribution of item severity from the psychometric sample described in the PTPB manual (Bickman et al., 2010). For all measures, response choices were Likert-type items with varied scales. The directionality of the Likert scales for each measure is indicated by low (lower scores are more severe) or high (higher scores are more severe).

The SRF is part of the larger Peabody Treatment Progress Battery (PTPB; Bickman et al., 2010) of measures of youth treatment process and progress. Eighteen of the 20 content domains correspond to other measures in the PTPB (the exceptions are “strengths of youth/family” and “client progress”). For example, the SRF topic “emotional issues” is a content domain that corresponds to 13 items related to internalizing symptoms reported by the youth, caregiver, and clinician on the Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale (SFSS) (Athay, Riemer, & Bickman, 2012). All of the PTPB measures have excellent psychometric properties, with further detail on each measure available elsewhere in this issue. Table 1 presents the PTPB measures used as sources of youth-related concerns by SRF topic. For each measure, the number of items that correspond to a given SRF topic is listed. All are Likert-type items and each item represents a ‘problem alert’ when rated in the top 25% of the distribution of item severity from the psychometric sample described in the PTPB manual (Bickman et al., 2010). Problem alerts are item and informant specific, so the same item may have different alert levels for caregivers, youth, and clinicians. For example, responses for the SFSS item “how often did you [did this youth] feel unhappy or sad” ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). For all three respondents, a rating of 4 (often) to 5 (very often) was in the top 25th percentile of severity. Thus a rating of 4 or 5 on this item for any respondent would be counted as a problem alert corresponding to the SRF topic of emotional issues. As another example, the item “getting counseling seems like a good idea to me” was included with slightly different wording in both the youth and the caregiver versions of the Motivation for Youth's Treatment Scale (MYTS; Breda & Riemer, 2012). With a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), ratings in the top 25th percentile of severity differed by respondent with youth ratings of 1 (strongly disagree) or 2 (disagree) and caregiver ratings of 1 to 3 (neither agree nor disagree). Thus, whether this item was counted as a problem alert for the SRF topics of client motivation for treatment or caregiver motivation for treatment differed by respondent. Note that for the SFSS, some items were categorized into more than one SRF topic domain.

Procedures

All measures were administered using paper- and pencil-forms at the close of a treatment session. While the SRF was scheduled to be administered at each session, other PTPB measures had varying schedules as shown in Table 1. Each informant was instructed to complete his or her own measures privately, at which point the measures would be placed into an envelope that was then sealed. An administrative assistant later entered the measures into the computer. Thus, the administration was designed so that the clinician did not see the youth or caregiver responses to any of the measures at the time the SRF for that session was completed.

Analyses

At each session, clinicians documented whether they addressed, focused on, or did not address SRF topics as part of that treatment encounter. In addition, youths, caregivers, and clinicians completed measures relevant to treatment process and progress resulting in item-level problem alerts corresponding to specific SRF topics. Thus, the session is the unit of analysis. Clinician-reported session content is the main outcome of interest in this study. Since the dependent variable is categorical (i.e. the extent to which a topic was addressed), we used Multilevel Multinomial Logit Models (MMLM) to estimate simultaneously the parameters, odds ratios and predicted probabilities of session content as reported by the clinician. MMLM estimates multiple equations simultaneously by maximum-likelihood methods while at the same time controlling for the nesting of clients within clinicians (Skrondal & Rabe-Hesketh 2003; Hedeker, 2003). The multilevel multinomial logit model is a mixed generalized linear model with linear predictors and multinomial logit link (Grilli & Rampichini, 2007). In our analyses, clinicians have three possible responses (addressed, focused on, or not addressed); therefore by using MMLM we estimate two responses with respect to the third response (the reference group), deriving the parameter estimates simultaneously. From the parameters of these two equations, it is possible to derive the effects of unit changes in the independent variables on the probability of each response. The independent variables were the count of problem alerts (from the PTPB study measures) related to that particular SRF content domain.

The models were estimated using Proc GlimMix in Sas 9.12, with a separate model for each SRF topic and informant. Jointly, each model assessed two equations producing four parameters: two intercepts and two slope coefficients. The first equation predicts the log odds of “addressing the topic” vs. “not addressing the topic.” The second equation predicts the log odds of “addressing as an important focus of the session” vs. “not addressing the topic.” Positive and significant intercepts suggest that addressing/focusing on the topic is more common than not addressing the topic. Positive and significant slopes suggest that problems reported by the informants are correlated with clinician-reported session content. Because estimates using log odds are difficult to interpret, we also provide the odds ratio for each slope coefficient.

Due to the large number of models the significance level was set at a conservative p < 0.001. Note that caregiver motivation for youth's treatment and satisfaction with services could not be modeled. For each of these SRF topics, there was no variance in the number of problem alerts reported by the caregiver when the topic was considered an important focus of a session by the clinician.

Results

Clinicians provided SRF information on 3,143 sessions representing 83% of all recorded sessions. The number of sessions with SRF data available for each youth varied widely, from one to 48 sessions, over a time period from one week to 17 months. The median treatment course over which SRF data were available was 10 sessions (SD=9.1) over 3.9 months (SD=3.0). Session characteristics recorded on the SRF included session length, location, and participants. About one quarter of sessions lasted 31-60 minutes (26%) and very few lasted half an hour or less (3%). The remaining sessions were more than one hour (47% one to two hours; 24% more than two hours). Treatment usually occurred in the client‘s home (70%) with few sessions in other settings (7% in client‘s school, 11% in an outpatient clinic/center, 11% other). The youth was present in almost all sessions (95%). About a third (29%) of sessions were held with the youth only although the modal session (58%) consisted of the youth and one or more family members together. Few sessions (12%) included other participants (e.g., school personnel) with or without the participation of the youth and family.

An SRF item asked clinicians to mark how much time in the session was spent dealing with crisis using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from none to most or all. Most sessions (79%) did not include any time spent dealing with a crisis. A little time was spent on a crisis for 13% of sessions, half of the session was spent on a crisis for 4% of sessions, and most or all of the session was spent dealing with a crisis for another 4%. Another SRF item asked clinicians to provide an overall rating of the session on a 5-point Likert scale from excellent to very poor. The typical session was rated as “good” (Mean=4.0, SD=0.6). Very few sessions (2%) were rated as somewhat or very poor by the clinician.

In a typical session, clinicians provided information on 19.3 (SD=3.1) topics, indicating minimal missing data. Clinicians addressed an average of 7.2 distinct topics per session (SD=4.0), while fewer topics (Mean=1.7, SD=2.1) were described as being an important focus of the session. Table 2 presents the percentage of sessions where SRF topics were addressed or an important focus. According to clinicians, topics such as emotional or friends/peer issues were addressed or focused on frequently. Other topics, such as alcohol/substance use and caregiver strain were not addressed in most sessions.

Table 2.

Descriptive Information for All Sessions (N=3,143): Clinician-Reported Content Addressed or an Important Focus and Problem Alerts (Reported by Clinician, Youth, or Caregiver) by SRF Topic

| SRF Topic | Session Content | Problem Alerts Per Session | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician | Youth | Caregiver | ||||||||||

| N | % Add | % Focus | N | % Any Probs | Median # Probs | N | % Any Probs | Median # Probs | N | % Any Probs | Median # Probs | |

| Emotional issues | 3075 | 57.6 | 23.6 | 1341 | 89.5 | 5 | 1106 | 76.5 | 3 | 728 | 84.2 | 4 |

| Behavioral issues | 3081 | 57.7 | 24.1 | 1341 | 82.8 | 4 | 1105 | 84.2 | 5 | 728 | 79.0 | 3 |

| Family issues | 3073 | 55.8 | 30.1 | 1341 | 71.8 | 1 | 1105 | 63.3 | 1 | 725 | 45.5 | 0 |

| School/work issues | 3065 | 56.4 | 18.4 | 1341 | 65.6 | 1 | 1105 | 60.4 | 1 | 725 | 56.7 | 1 |

| Friends/peer issues | 3062 | 58.0 | 11.2 | 1341 | 82.1 | 2 | 1103 | 67.8 | 1 | 721 | 72.5 | 2 |

| Problems w/delinquent behavior | 3024 | 17.3 | 3.7 | 1341 | 53.2 | 1 | 1105 | 51.0 | 1 | 727 | 53.4 | 1 |

| Alcohol/substance use | 3019 | 13.9 | 4.9 | 1339 | 21.8 | 0 | 1105 | 21.2 | 0 | 721 | 18.7 | 0 |

| Harm to self or others | 3034 | 16.7 | 2.8 | 1327 | 24.0 | 0 | ||||||

| Client hope for future | 3033 | 53.0 | 7.7 | 316 | 29.7 | 0 | ||||||

| Client motivation for treatment | 3044 | 40.4 | 4.6 | 270 | 31.9 | 0 | ||||||

| Therapeutic relationship w/client | 3027 | 23.9 | 2.0 | 1149 | 32.2 | 0 | ||||||

| Client perceptions on counseling impact | 3023 | 34.0 | 2.8 | 482 | 35.3 | 0 | ||||||

| Client satisfaction w/services | 3019 | 30.3 | 1.9 | 306 | 16.0 | 0 | ||||||

| Caregiver strain | 2978 | 29.3 | 7.7 | 199 | 71.4 | 2 | ||||||

| Caregiver satisfaction w/life | 2988 | 23.4 | 3.0 | 241 | 43.6 | 0 | ||||||

| Caregiver motivation for youth treatment | 2983 | 27.4 | 3.6 | 188 | 29.8 | 0 | ||||||

| Therapeutic relationship w/caregiver | 2970 | 13.7 | 1.4 | 716 | 33.2 | 0 | ||||||

| Caregiver satisfaction w/services | 2971 | 20.5 | 2.1 | 199 | 3.0 | 0 | ||||||

1 Note: % Add= Percent of sessions content was addressed; % Focus=Percent of sessions content was an important focus. The percent of sessions where a topic was not addressed is calculated by subtracting % Add and % Focus from 100.

2 Note: % Any Probs=Percent of sessions where one or more problem alerts was reported. In addition to the median number of problem alerts per session, the maximum number of problem alerts was the total number of items corresponding to each SRF topic as resented in Table 1; the minimum for all was zero.

The number of problem alerts per session by informant, derived from the PTPB measures described previously (see Table 1), varied widely. As presented in Table 2, problem alerts related to the first five SRF topics (emotional issues to friends/peer issues) were commonly reported in sessions by all three informants. In addition, caregivers reported one or more problem alerts corresponding to caregiver strain for almost three-quarters of all sessions where this information was recorded. In contrast, the median number of problem alerts corresponding to several SRF topics was zero, particularly for topics related to the treatment process (e.g., motivation for treatment, therapeutic relationship).

Session Content Addressed or Focused on in the Absence of Problem Alerts Varied by Topic

The results of the MMLM analyses are presented in Table 3. The intercepts measure the log-odds of addressing or focusing on a content area compared to the reference group (not addressed) when there are no problem alerts (problem alerts=0). When informants do not report any problem alerts, positive intercepts indicate a greater probability of addressing or focusing on a content area compared to not being addressed, while negative intercepts indicate a lower probability. The slopes are the multinomial logit estimates for a one unit increase in the number of problem alerts reported by the informants on clinician-reported content addressed or focused on in sessions compared to the reference group (not addressed).

Table 3.

Results of Multilevel Multinomial Logit Models (Estimates of Intercepts and Slopes) of Session Content Addressed or Focused on by SRF Topic and Informant

| SRF Topic | Informant1 | N | Addressed Topic | Focused on Topic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. Intercept2 | Est. Slope3 | Est. Intercept2 | Est. Slope3 | |||

| Emotional issues | Cl | 1297 | 0.95* | 0.10 | −0.91 | 0.17* |

| Y | 1089 | 1.21* | 0.08 | −0.52 | 0.16* | |

| Cg | 716 | 1.12* | 0.05 | −0.35 | 0.08 | |

| Behavioral issues | Cl | 1303 | 0.88* | 0.12* | −1.25* | 0.28* |

| Y | 1091 | 1.23* | 0.03 | −0.20 | 0.07 | |

| Cg | 718 | 1.31* | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.13* | |

| Family issues | Cl | 1296 | 1.38* | 0.21 | −0.13 | 0.53* |

| Y | 1088 | 1.42* | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.39* | |

| Cg | 714 | 1.71* | −0.04 | 0.56 | 0.15 | |

| School/work issues | Cl | 1293 | 0.72* | 0.05 | −1.03* | 0.38 |

| Y | 1087 | 0.89* | −0.07 | −0.55 | 0.05 | |

| Cg | 710 | 0.57* | 0.14 | −0.73 | 0.23 | |

| Friends/peer issues | Cl | 1295 | 0.43* | 0.10 | −1.64* | 0.21* |

| Y | 1087 | 0.63* | 0.06 | −1.45* | 0.20* | |

| Cg | 707 | 0.41 | 0.09 | −1.50* | 0.12 | |

| Problems w/delinquent behavior | Cl | 1275 | −2.09* | 0.38* | −3.73* | 0.58* |

| Y | 1075 | −1.83* | 0.09 | −3.74* | 0.40 | |

| Cg | 704 | −1.69* | 0.15 | −3.67* | 0.48 | |

| Alcohol/substance use | Cl | 1273 | −2.22* | 1.09* | −3.97* | 1.41* |

| Y | 1074 | −1.98* | 0.68* | −3.55* | 1.29 | |

| Cg | 697 | −2.02* | 0.87* | −4.10* | 1.29 | |

| Harm to self or others | Cl | 1272 | −2.00* | 1.09* | −4.20* | 1.61* |

| Client hope for future | Y | 305 | 0.25 | 0.23 | −1.45* | 0.19 |

| Client motivation for treatment | Y | 261 | 0.33 | −0.15 | −1.78* | 0.05 |

| Therapeutic relationship w/client | Y | 1114 | −1.17* | 0.15 | −4.09* | 0.31 |

| Client perceptions on counseling impact | Y | 467 | −0.34 | 0.10 | −2.76* | 0.07 |

| Client satisfaction w/services | Y | 298 | −0.62 | 0.20 | −3.14* | 0.35 |

| Caregiver strain | Cg | 194 | −0.47 | 0.19 | −2.69* | 0.37 |

| Caregiver satisfaction w/life | Cg | 234 | −0.80 | 0.09 | −2.97* | 0.21 |

| Therapeutic relationship w/caregiver | Cg | 690 | −1.26* | −0.08 | −3.62* | 0.00 |

Note: Y=Youth; Cg=Caregiver; Cl=Clinician.

Intercepts give the estimated log-odds of addressing or focusing on a content area relative to the reference group (not addressed) when informants do not report any problem alerts (problem alerts =0).

Slopes are the multinomial logit estimate for one unit increase in the number of problem alerts reported by the informants on clinician-reported content addressed or focused on in sessions compared to the reference group (not addressed).

p < 0.001.

There were positive and significant intercepts for addressing emotional, behavioral, family, school/work, and friends/peer issues, indicating these SRF topics are more likely to be addressed than not in sessions where there are no reported problem alerts. Conversely, there were negative and significant intercepts for addressing problems with delinquent behavior, alcohol/substance use, harm to self or others, and the therapeutic relationship with the client and the caregiver. This indicates that these topics are not likely to be addressed in sessions where there are no reported problem alerts. All intercepts for focusing on topics were negative, with many in the significant range, indicating that in the absence of problem alerts these topics were rarely a focus of session content.

Effect of Problem Alerts on Session Content Addressed or Focused On Varied by Topic and Informant

Because MMLM intercepts and slopes are calculated as log odds and are thus difficult to interpret, Table 4 presents the proportional odds ratio of each slope by SRF topic area and informant for the corresponding problem alerts. Recall that problem alerts were not something the clinician could see at the time they completed the SRF but were calculated after the session to reflect the severity of an informant's responses to an item or group of items. Each odds ratio represents the probability of a one unit increase in the number of problem alerts documented during the session on the content addressed or focused on in that session given that other variables in the model are held constant. Thus, for a one unit increase in alcohol/substance use problem alerts reported by any informant, the odds of addressing alcohol or substance use in a session ranges from 2.0 to 3.0 times greater (depending on informant) than not addressing that topic in the session. Likewise, the odds of addressing alcohol or substance use as an important focus in a session ranged from 3.6 to 4.1 times greater (depending on informant) than not addressing that topic in the session.

Table 4.

Proportional Odds Ratios of Estimated Log Odds Slopes from Multilevel Multinomial Logit Models: Effect of Increasing Number of Problem Alerts on Clinicians’ Addressing or Focusing on Session Content by SRF Topic and Informant

| SRF Topic | Possible # Problems | Addressed Topic1 | Focused on Topic1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl2 | Y2 | Cg2 | Cl2 | Y2 | Cg2 | ||

| Emotional Issues | 13 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.19* | 1.17* | 1.08 |

| Behavioral issues | 16 | 1.13* | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.33* | 1.07 | 1.14* |

| Family issues | 4 | 1.23 | 1.15 | 0.96 | 1.70* | 1.48* | 1.16 |

| School/work issues | 3 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.15 | 1.47 | 1.05 | 1.26 |

| Friends/peer issues | 6 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.24* | 1.22* | 1.12 |

| Problems w/delinquent behavior | 3 | 1.47 | 1.09 | 1.17 | 1.79* | 1.49 | 1.61 |

| Alcohol/substance use | 2 | 2.97* | 1.97* | 2.39* | 4.11* | 3.63* | 3.63* |

| Harm to self or others | 1 | 2.99* | 5.00* | ||||

| Client hope for future | 4 | 1.26 | 1.21 | ||||

| Client motivation for treatment | 4 | 0.86 | 1.05 | ||||

| Therapeutic relationship w/client | 5 | 1.16 | 1.36 | ||||

| Client perceptions on counseling impact | 6 | 1.11 | 1.07 | ||||

| Client satisfaction w/services | 4 | 1.22 | 1.42 | ||||

| Caregiver strain | 7 | 1.21 | 1.44 | ||||

| Caregiver satisfaction w/life | 5 | 1.10 | 1.23 | ||||

| Therapeutic relationship w/caregiver | 5 | 0.93 | 1.00 | ||||

Proportional odds ratio of addressing or focusing on a content area compared to the reference group (not addressed).

Informant of problem alerts: Y=Youth; Cg=Caregiver; Cl=Clinician.

p < 0.001.

Notably, youth alcohol or substance use is the only SRF topic with problem alerts reported by multiple informants where the odds of the clinician addressing or focusing on that content area was significant across all three informants. When problem alerts were reported on the PTPB measures by clinicians, the odds of addressing the corresponding content area as an important focus in a session were significantly higher than not addressing it for six of the seven SRF topics. In addition, the probability of simply addressing the corresponding content area was significant for two SRF topics (behavioral issues and alcohol/substance use) when clinicians reported problem alerts.

The effect of problem alerts on the clinician addressing the corresponding content as an important focus of a session differed by youth- or caregiver-informant. In addition to alcohol/substance use, youth-reported problem alerts were associated with increased odds for three SRF topic areas: emotional, family, and friends/peer issues. Caregiver-reported problem alerts were associated with increased odds for only one other SRF topic area (behavioral issues). There were no differences in the odds of addressing or focusing on school/work issues for problem alerts reported by any informant. Similarly, there were no significant findings for the SRF topics corresponding to single-informant PTPB measures with one exception. The item for youth harm to self or others was only included on the SFSS completed by the clinician. When the clinician's response was in the problem alert range, the odds of session content addressing or focusing on youth harm to self or others was significantly increased

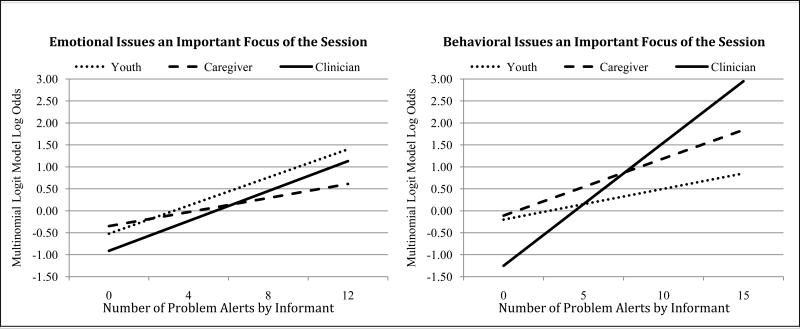

To assist with interpretation of these informant differences, Figure 1 presents a graphical representation of the predicted trajectories of emotional and behavioral issues addressed as an important focus of the session by the number of problem alerts reported by each informant. The two graphs in the figure illustrate the different relationships between youth- and caregiver-reported problem alerts and clinician-reported content focus by SRF topic.

Figure 1.

Predicted Trajectories of Emotional and Behavioral Issues Addressed as an Important Focus of the Session by Number of Problem Alerts for Each Informant

For emotional issues, there is a substantial increase in the probability of the clinician focusing on that topic in session with a corresponding increase in the number of problem alerts reported by youth; whereas a focus on emotional issues only increases slightly with the number of problem alerts reported by caregivers. In contrast, addressing behavioral issues as an important focus of a session increases substantially with the number of problem alerts reported by caregivers, but only increases slightly for problem alerts reported by youth. Clearly for both emotional and behavioral issues, the number of clinician-reported problem alerts is associated with a substantial increase in addressing that topic as a focus of the session.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between content addressed or focused on in sessions, documented on the Session Report Form (SRF) by the clinician, and youth-related concerns reported by multiple informants. The clinician, youth, and caregiver each completed a battery of treatment process and progress measures (PTPB; Bickman et al., 2010) at the close of a session. Individual items from these measures were linked to specific content areas, with ‘problem alerts’ representing those items rated in the top quartile. The only measures viewed by clinicians at the time of the session were their own; youth- and caregiver-reported measures were designed to be completed privately. Further, the calculation of problem alerts occurred after the session, and thus was not available to the clinician at the time they completed the SRF. With previous research showing good internal consistency and feasibility of use in routine care (Kelley et al., 2010), the results add support to the utility of the SRF for describing practice in routine mental health settings with additional evidence of convergent validity stemming from the positive correlations between the clinicians’ report of session content and youth-related problems. In addition, several interesting patterns emerged from the investigation of how clinician-reported therapy process (operationalized as session content) was associated with youth- and caregiver-reported problems, as well as how the relationship between session content and youth-related problems differed by content area. Study results are described further below in addition to a discussion of the research limitations and future directions.

First, as hypothesized there was a strong relationship between clinician-reported problem alerts and a corresponding focus on content within the session for all but one topic area (school/work issues). Clinicians’ report of addressing emotional issues, behavioral issues, family issues, friends/peer issues, problems with delinquent behavior, and youth alcohol/substance use was associated with their own report of corresponding problem alerts. This likely reflects the clinician's own perceptions of youth-related problems. Where the clinician reports more concerns, he or she may simply be more likely to address those content areas as a focus within that session. It seems reasonable to conclude that the clinician perception of an issue as a problem is a necessary precondition for addressing those problems in treatment. This finding lends further support to the convergent validity of the SRF as a useful measure for assessing practice in routine mental health care settings (Kelley et al., 2010; Schoenwald et al., 2011). As a caution, given the correlational nature of the analyses, no causal directionality between session content and problem alerts can be inferred.

Second, also as hypothesized, there were fewer relationships between clinician-reported content and youth- and caregiver-reported problem alerts. However, in contrast to our original hypothesis, it appears that clinicians are more likely to address content related to current problems reported by the youth rather than the caregiver (four and two problems respectively). Research on multi-informant agreement that suggests that clinicians tend to agree more with parents than youths with similar age ranges as in our study on a variety of measures. This includes functioning impairment (Kramer et al., 2004) and target problems (Hawley & Weisz, 2003) assessed at intake for youths treated in the community. Other research has found similar results for pre- and post-symptom improvement for youths participating in a randomized control trial for social phobia treatment (De Los Reyes, Alfano, & Beidel, 2011). Caregivers have also been judged to be more credible reporters than youths, although youth credibility increased with age (De Los Reyes, Youngstrom et al., 2011; Youngstrom et al., 2011).

Our hypothesis was only partially confirmed regarding differences in the association of session content with problems reported by youth and caregivers. With the exception of alcohol/substance use, there was no overlap between session content and youth- and caregiver-reported problem alerts related to youth symptoms and functioning. As expected, content was associated with youth-reported problems related to family and friend/peer issues but not with caregiver reports of the same problems (e.g., Hawley & Weisz, 2003). Also as expected, session content was related to caregiver-report of youth behavioral issues. However, the relationship between content and emotional issues was significant for youth-reported problems but not caregivers. Further, there was no relationship between content and school/work issues or problems with delinquent behavior reported by either the youth or the caregiver. In contrast, Hawley and Weisz (2003) found that clinicians agreed more at intake on target problems related to symptoms (e.g., emotional and behavioral problems) reported by caregivers, and aggressive/delinquent behaviors reported by both youth and caregivers. Kramer and colleagues (2004) found that clinicians rated youth functioning problems at intake as more serious when youths reported illegal or delinquent behavior rather than when parents alone reported these behaviors.

Of course, a major difference is that these studies all investigated agreement on measures of youth problems, while our study explored the relationship between session content and concurrent reports of youth-related problems. Thus, it may be that clinicians are in greater agreement with caregivers on various issues, but they may adjust their behavior or verbal interactions in treatment sessions based on the issues most relevant to youths. Further, our study used session-based measures completed throughout treatment while the previously referenced studies used one or two time points (e.g., intake, pre- and post-treatment). It may be that clinicians respond differently to youths and caregivers during the course of treatment as opposed to an initial assessment. For our sample, the youth was almost always present in the session and the caregiver was present about 60% of the time. While clinician awareness of other-reported problems is not known, it may be that clinicians were more attuned overall to problems experienced by the youth rather than the caregiver simply due to greater exposure to the youth during the course of treatment. Future research is warranted to further explore the influence of multiple participants in the session (e.g., caregiver and youth, youth only) and their agreement on problems within a session on content. Without causal data to shed light on the clinician's internal decision-making process about what to focus on in sessions, we can only speculate on the influence of factors such as prior awareness of and perceived credibility of information from youths and caregivers. Future research should increase our understanding of what clinicians do in sessions in light of recent recommendations on how to incorporate multi-informant assessment into treatment to improve outcomes (Achenbach, 2011; De Los Reyes, 2011; Weisz et al., 2011).

We also found that the relationship between content focus in sessions and problem alerts differed by type of problem. The likelihood for clinicians to report addressing some topics (emotional, behavioral, family, school/work, and friends/peer issues) was very high even in the absence of problem alerts. Other topics (delinquent behavior, alcohol/substance use, harm to self or others, and the therapeutic relationship with the client and the caregiver) were not likely to be addressed in sessions where there were no reported problem alerts. This suggests that there may be patterns in the types of issues commonly raised in youth mental health treatment sessions, regardless of problems currently being reported.

Where problem alerts had been reported, all of the significant relationships were for content related to youth symptoms and functioning, with the SFSS (Athay, Riemer, & Bickman, 2012) as the source of items. This was true regardless of whether problems were infrequent (e.g., clinicians reported concerns about youth alcohol/substance use and harm to self/others in 22 to 24% of sessions respectively) or common (e.g., behavioral problem alerts were reported in 79 to 84% of sessions by all informants). Encouragingly, the findings were particularly strong for high severity problems including alcohol/substance use and harm to self/others. Troublingly, there was no significant relationship between caregiver-reported strain and a corresponding content focus. Caregiver strain has been found to be associated with youth symptoms and functioning (Brannan, Athay, & Vides de Andrade, 2012). Thus, it could be argued that high caregiver strain, when present, should be an important focus of youth treatment.

There was no association between session content and problems related to youth or caregiver strengths (e.g., client hope for the future, caregiver satisfaction with life) and the ‘common factors’ of treatment (e.g., motivation for treatment, therapeutic relationship; Kelley, Bickman, & Norwood, 2010). This finding is consistent with previous research on the SRF (Kelley et al., 2010) where clinicians accounted for 34% of the variance on topics related to the treatment process compared to 11% for the client. Perhaps this is indicative of a ‘personal style’ in a clinician's approach to the treatment process, whereas content related to youth symptoms and functioning is modified based on the client. Clinicians may also be less focused on problems that are not consistent with a traditional medical approach; that is, deficits in youth symptoms and functioning are the primary focus of treatment. An alternate explanation is that completing related measures raised clinicians’ awareness of problems. There were no significant associations between session content and youth- or caregiver-reported problem alerts when there was no corresponding clinician-reported measure. Note that although there is a clinician-reported measure of therapeutic alliance in the PTPB (see Bickman et al., 2012), no problem alerts were calculated with this measure and thus it is not included in this study.

In conclusion, this study extends the literature on multi-informant agreement of youth problems by examining the relationship between multiple perspectives (youth, caregiver, and clinician) and types (treatment progress and process) of problems and the content addressed or focused on in treatment sessions. However, there are several limitations of the research that must be noted. The majority of sessions occurred in the client's home with treatment provided by a master's level clinician; thus, the findings may not generalize to other treatment settings or clinician populations. Support for the validity and reliability of the SRF would be enhanced through further research in routine care settings that engage in other forms of treatment, such as in-clinic outpatient care. While limited information about clinicians, treatment provided, and clients was available given that the larger evaluation was conducted in a real world setting, organizational data show that study sites did not differ from a large number of non-evaluation sites on number, years employed, highest degree, or degree specialty of clinicians (Bickman et al., 2011).

Further, the SRF measures only the clinician's perception of session content, which may not be consistent with youth- or caregiver-perspectives or those of an outside observer. Other studies have shown low concordance between observer ratings and clinician self-report of therapeutic strategies used in routine treatment for youths with disruptive behavior problems (Hurlburt et al., 2010). Some of this discrepancy may be due to the unreliability of asking clinicians to report on specific therapeutic strategies or orientations without training, a problem that may not affect an instrument that simply measures session content. However, a clinician's self-report of session content may be capturing intent of practice rather than observable behaviors or verbal interactions. Continued development of the SRF would benefit from research that incorporates multiple methods, such as observational ratings, and multiple reporters to better understand the influence of reporter bias and the reliability of ordinal scaling (presence and amount) as compared to actual session content (e.g., Schoenwald et al., 2011).

Finally, the correlational nature of the study is a particularly important limitation. The lack of directionality between session content and problem alerts does not allow us to understand whether the clinician addressed or focused upon a specific content area because of a perceived problem. Because of the timing of data collection, where all measures including the SRF were completed at the close of a session, it is possible that the clinician's content focus influenced the client and caregiver reports of problems. Further, the current analyses appropriately account for the complexity of the sample (sessions nested within clients within clinicians), yet did not include important variables like time, clinician's awareness of youth- and caregiver-reported problems, characteristics of sessions (e.g., participants) and informants (e.g., age, race), and agreement on problems between informants. Future analyses are planned that include these variables within the models, which will allow us to explore variability in patterns associated with the course of treatment and establish a stronger causal linkage between clinician awareness of youth- and caregiver-reported problems and subsequent content addressed in future sessions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grants R01-MH068589 and 4264600201 awarded to Leonard Bickman.

References

- Achenbach TM. Commentary: Definitely more than measurement error: But how should we understand and deal with informant discrepancies? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(1):80–86. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533416. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.533416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athay MM. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) in caregivers of clinically-referred youth: Psychometric properties and mediation analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0390-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athay MM, Bickman L. The Service Satisfaction Scale: Psychometric evaluation and determinants of youth and parent satisfaction in community mental health treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athay MM, Riemer M, Bickman L. The symptoms and functioning severity scale (SFSS): Psychometric evaluation and differences of youth, caregiver, and clinician ratings over time. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0403-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. A measurement feedback system (MFS) is necessary to improve mental health outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(10):1114–1119. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825af8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Athay MM, Riemer M, Lambert EW, Kelley SD, Breda C, Tempesti T, Dew-Reeves SE, Brannan AM, Vides de Andrade AR, editors. Manual of the Peabody Treatment Progress Battery. 2nd ed. Vanderbilt University; Nashville, TN: 2010. [Electronic version] http://peabody.vanderbilt.edu/ptpb. [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Kelley S, Breda C, Vides de Andrade A, Riemer M. Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on youth mental health outcomes: A randomized cluster design. Psychiatric Services. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.002052011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Vides de Andrade AR, Athay MM, Chen JI, De Nadai AS, Jordan-Arthur B, Karver MS. A dynamic analysis of therapeutic alliance on change in severity of symptoms and functioning in youth receiving mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Brannan AM, Athay MM, Vides de Andrade AR. Measurement quality of the abbreviated Caregiver Strain Questionnaire. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breda CS, Riemer M. Motivation for Youth's Treatment Scale (MYTS): A new tool for measuring motivation among youths and their caregivers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Hepner KA, Miranda J. Future research on psychotherapy practice in usual care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0254-7. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0254-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A. Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Alfano CA, Beidel DC. Are clinicians’ assessments of improvement in children's functioning “global”? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(2):281–294. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Youngstrom EA, Swan AJ, Youngstrom JK, Feeny NC, Findling RL. Informant discrepancies in clinical reports of youths and interviewers’ impressions of the reliability of informants. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2011;21(5):417–424. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0011. doi:10.1089/cap.2011.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew-Reeves SE, Athay MM, Kelley SD. Examining the prediction of youth treatment progress by youth hope using the Children's Hope Scale – Revised PTPB Edition (CHS-PTPB). Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Bickman L, Chorpita BF. Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0279-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli L, Rampichini C. Multilevel factor models for ordinal variables. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, Nielsen SL, Smart DW, Shimokawa K, Sutton SW. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61(2):155–163. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20108. doi:10.1002/jclp.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SHB, Krieger K. Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists’ ability to detect negative client change. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2010;17(1):25–32. doi: 10.1002/cpp.656. doi:10.1002/cpp.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, Weisz JR. Child, parent, and therapist (dis)agreement on target problems in outpatient therapy: The therapist's dilemma and its implications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):62–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D. A mixed-effects multinomial logistic regression model. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:1433–1446. doi: 10.1002/sim.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt MS, Garland AF, Nguyen K, Brookman-Frazee L. Child and family therapy process: Concordance of therapist and observational perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(3):230–244. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0251-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist. 2008;63(3):146–159. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns MA, Athay MM. Measuring youths’ perceptions of counseling impact: Description, psychometric evaluation, and longitudinal examination of the Revised Youth Counseling Impact Scale. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0414-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SD, Bickman L. Beyond outcomes monitoring: Measurement feedback systems (MFS) in child and adolescent clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2009;22(4):363–368. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c9162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SD, Bickman L, Norwood E. Evidence-based treatments and common factors in youth psychotherapy. In: Duncan BL, Miller SD, Wampold BE, Hubble MA, editors. The heart and soul of change: What works in therapy. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2010. pp. 325–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SD, Vides de Andrade AR, Sheffer E, Bickman L. Exploring the black box: measuring youth treatment process and progress in usual care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(3):287–300. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0298-8. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer TL, Phillips SD, Hargis MB, Miller TL, Burns BJ, Robbins JM. Disagreement between parent and adolescent reports of functional impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):248–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love SM, Koob JJ, Hill LE. Meeting the challenges of evidence-based practice: Can mental health therapists evaluate their practice? Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2007;7(3):184–193. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR. The therapy process observational coding system for Child Psychotherapy Strategies Scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:436–443. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Azocar F, Burnam MA. Assessment of evidence-based psychotherapy practices in usual care: Challenges, promising approaches, and future directions. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(3):205–207. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BJ, Daleiden EL, Mueller CW. Validity of treatment target progress ratings as indicators of youth improvement. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(5):729–741. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Chapman JE, Frazier SL, Sheidow AJ, Southam-Gerow MA. Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):32–43. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0321-0. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton TL, Kelley SD. Finding the common core: Evidence-based practices, clinically relevant evidence, and core mechanisms of change. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(1-2):81–88. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0277-0. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S. Multilevel logistic regression for polytomous data and rankings. Psychometrika. 2003;68:267–287. [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Weisz JR, Donenberg GR. Development of the therapy procedures checklist: A therapist-report measure of technique used in child and adolescent treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;31(2):168–180. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Frye A, Ng MY, Lau N, Bearman SK, Ugueto AM, Langer DA, Hoagwood KE. Youth top problems: Using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(3):369–380. doi: 10.1037/a0023307. doi:10.1037/a0023307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Youngstrom JK, Freeman AJ, De Los Reyes A, Feeny NC, Findling RL. Informants are not all equal: Predictors and correlates of clinician judgments about caregiver and youth credibility. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2011;21(5):407–415. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0032. doi:10.1089/cap.2011.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, Friedman M, Attiullah N, Boerescu D. How should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient's perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:148–150. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]