Abstract

Objective

Maternal high fat diet programs an increased risk of offspring obesity and systemic hypertension. Although the renal renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is known to regulate blood pressure, it is now recognized that the RAS is also activated in adipose tissue during obesity. We hypothesized that programmed offspring hypertension is associated with activation of the adipose tissue RAS in the offspring of obese rat dams.

Study Design

At 3 weeks of age, female rats were weaned to a high fat (HF: 60% k/cal; n=6) or control (control, 10% k/cal; n=6) diet. At 11 weeks of age, these rats were mated and continued on their respective diets during pregnancy. After birth, at 1 day of age, subcutaneous adipose tissue was collected, litter size was standardized and pups were cross-fostered to either control or HF dams, creating 4 study groups. At 21 days of age, offspring were weaned to control or HF diet. At 6 months of age, body fat and blood pressure were measured. Thereafter, subcutaneous and retroperitoneal adipose tissue was harvested from male offspring. Protein expression of adipose tissue RAS components were determined by Western Blotting.

Results

Maternal high fat diet induced early and persistent alterations in offspring adipose RAS components. These changes were dependent upon the period of exposure to the maternal high fat diet, were adipose tissue specific (subcutaneous and retroperitoneal), and were exacerbated by a postnatal high fat diet. Maternal high fat diet increased adiposity and blood pressure in offspring, regardless of the period of exposure.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that programmed adiposity and activation of the adipose tissue RAS are associated with hypertension in offspring of obese dams.

Keywords: subcutaneous and retroperitoneal adipose tissue, pregnancy, lactation, angiotensinogen, rat

Introduction

Obesity and its associated health problems represent a worldwide epidemic.1 Maternal obesity has been shown to increase the risk of offspring obesity and its related diseases, such as heart disease, stroke and hypertension.2-4 Hence, as the prevalence of obesity among pregnant women continues to rise, an increasing number of children are exposed to an ‘obese intrauterine environment’ during development. It is clear that there is a strong correlation between the incidence of hypertension and obesity, more specifically visceral and abdominal obesity.5 According to data from the Framingham Cohort, obesity by itself accounts for 78% and 65% of essential hypertension in men and women, respectively.6 Although the mechanisms underlying these associations are not fully elucidated, adipose tissue clearly is a critical factor in the development of obesity-hypertension.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a classic endocrine system involved in blood pressure homeostasis. Angiotensinogen (AGT), the precursor of the bioactive peptide, angiotensin II (Ang II), is synthesized mainly in the liver and enzymatically cleaved in the circulation by renin to angiotensin I (Ang I) and subsequently by the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) to Ang II. The major vasopressor effects of Ang II are mediated through its receptor type 1 (AT1) whereas its interaction with receptor type 2 (AT2) modulates cell proliferation and renal sodium excretion.7 In addition to the classical pathway of Ang II synthesis, adipose tissue has the ability to synthesize Ang II independent of the circulating RAS.8 Recent observations indicate that all components of the RAS are expressed in white adipose tissue from rodents9-11 and humans,12-14 suggesting that the adipogenic RAS may be involved in the pathogenesis of obesity-related hypertension. Accordingly, studies have shown that adipose-derived AGT can contribute to approximately 20% of plasma AGT concentrations and can modulate blood pressure.7 Angiotensinogen-knockout (AGT-KO) mice are hypotensive with hypotrophic adipocytes and adipose tissue-specific AGT gene expression in AGT-KO mice limits AGT expression to the adipose tissue but results in systemic concentrations of AGT levels that are 20% of wild-type levels, demonstrating that AGT produced in adipocytes can enter the circulation.15 Furthermore, over-expression of adipose AGT in mice induces hypertension with increased body fat and plasma AGT levels, indicating that an increased adipose tissue mass may result in higher circulating AGT levels, a finding confirmed in obese individuals.15

Increasing evidence suggests that adult cardiovascular and metabolic disorders can be “programmed” in utero16 and in the early postnatal period.17-19 Notably, both maternal under- or over-nutrition results in offspring obesity and hypertension.18,20-21 Despite this convincing evidence, there are no studies that have investigated the regulation of the adipogenic RAS in programmed, obesity-mediated hypertension. We hypothesized that the adipose tissue RAS is activated in the obese, hypertensive offspring that were exposed to maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and/or lactation. We determined the protein expression of adipose RAS components in newborns and adult offspring exposed to maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and/or lactation. We further investigated the changes in visceral and non-visceral adipose tissue and the additive impact of a high fat, post-weaning diet on the adipose RAS.

Materials and methods

A rat model of maternal obesity was created using a high fat diet prior to mating and throughout pregnancy and lactation. Studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–University of California, Los Angeles and were in accordance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Care and National Institutes of Health guidelines. Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Hollister, CA) were housed in a facility with constant temperature and humidity and a controlled 12:12-hour light/dark cycle. Weanling female rats were fed a high fat (HF; 60% k/cal fat, 20% k/cal protein, 20% k/cal carbohydrate; D12492, Research Diets Inc, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA; n=6) or normal fat control diet (Con; 10% k/cal fat, 20% k/cal protein, 70% k/cal carbohydrate; n=6) diet. At 11 weeks of age, rats were mated and continued on their respective diets during pregnancy and lactation.

Offspring

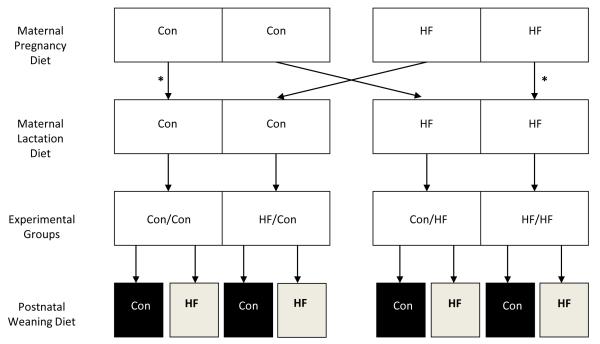

At birth, pups were culled to eight per litter (4 males and 4 females) to normalize rearing, and were cross-fostered, thereby generating four paradigms of maternal diets during pregnancy/lactation (Figure 1). To control for the cross-fostering effects, Con and HF pups were similarly cross-fostered amongst dams of the same group (Figure 1). At 3 week of age, offspring in each of the four groups were housed individually and weaned. To examine the effects of a high-fat diet, one male from each litter was randomly weaned to normal fat diet and one male was weaned to high-fat diet . Thus, there were four maternal feeding paradigms during pregnancy/lactation (Con or HF) and two offspring feeding paradigms (Con or HF) examined for male offspring (Figure 1). We elected to study males as females would have required estrus assessment, because estrogen is known to affect adiposity and lipid metabolism.22

Figure 1. Study design.

Experimental groups are: 1) maternal control diet during pregnancy and lactation (Con/Con); 2) maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and lactation (HF/HF); 3) maternal high fat diet during pregnancy alone (HF/Con); and 4) maternal high fat diet during lactation alone (Con/HF). Offspring from each experimental group were weaned onto either a control (Con) or high fat (HF) postweaning diet. To control for the cross-fostering effects, Con and HF pups were similarly cross-fostered amongst dams of the same group (*).

Body weight and composition

Male offspring were weighed at 1 day and at 6 months of age. In addition, at 6 months of age a noninvasive dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan was performed, using the DXA system with a software program for small animals (6 males from 6 litters per group and per post-weaning diet; QDR 4500A; Hologic, Bedford, MA). An in vivo scan of whole body composition was obtained that allowed determination of the percentage of body fat.

Blood Pressure

Measurements were undertaken in conscious animals using non-invasive Tail-cuff sphygmomanometry (ML125 NIPB System, AD Instruments) method. Several cuff sizes are used depending on the weight of the animal. To circumvent the potential problem of restrain-induced stress, the animals were acclimatized for at least one week with placement in the restraint. As adult offspring weaned to high fat diet had markedly increased body weights, we were unable to measure blood pressure due to unavailability of tail-cuff size in that range.

Tissue collection, protein extraction and Western Blotting

At 1 day of age subcutaneous adipose tissue was collected and tissue was pooled from 4 males per litter. In each group 6 litters were studied. At 6 months of age, both subcutaneous and retroperitoneal (visceral) intra-abdominal fat depot adipose tissue were collected; 6 males from 6 litters per group and per postnatal weaning diet were studied, Adipose tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C till protein analysis. Protein was extracted in radioimmuno precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer that contained protease inhibitors (HALT cocktail, Pierce). Supernatant protein concentration was determined by BCA solution (PIERCE, Rockford, IL). Protein expression was determined as previously described.21 The primary and secondary antibodies were: AGT (Santa Cruz SC-7419) Primary 1:500, Secondary 1:2000; ACE (Santa Cruz SC-23909) Primary 1:500, Secondary 1:2000; AT1 ( Santa Cruz SC-1573) Primary 1:500, Secondary 1:2000; AT2 (Santa Cruz SC-9040) Primary 1:500, Secondary 1:2000. All commercial antibodies were optimized for binding specificity and bands depicted have the expected molecular weights.

Statistical analysis

At 1 day of age, differences between HF and Controls were compared by unpaired Students’ t-test. At 6 months of age, differences between the four groups were compared by one way or two way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as approproiate, with experimental group (for example: Con/Con) and post-weaning diet (Con or HF) as factors and with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Body Weights and Body Fat

Consumption of a high fat diet resulted in maternal obesity both at term (Control dams: 378 ± 4g versus HF dams: 430 ± 7g; P<0.05) and at the end of the lactation period (Control dams: 309 ± 5g versus HF dams: 345 ± 6g; P<0.05).

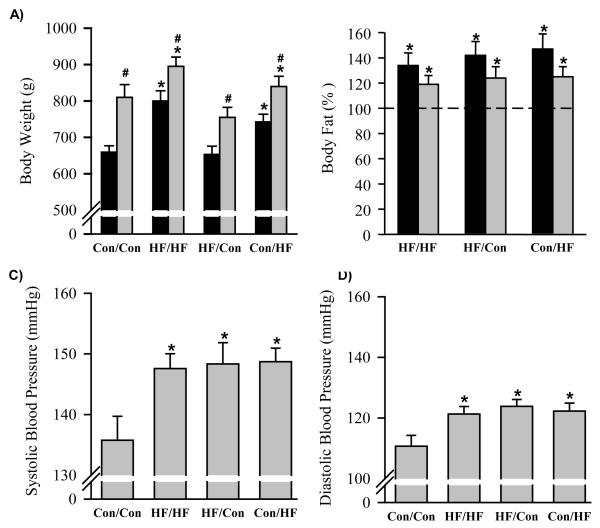

At 1 day of age, HF male newborns had similar body weights to the Controls (7.4±0.2 vs. 7.3±0.1 g). However, the maternal diet during lactation had a significant impact on body weights of the adult offspring. HF newborns nursed by HF dams (HF/HF) and weaned to a normal fat diet exhibited significantly higher body weights at 6 months of age, whereas HF newborns nursed by control dams (HF/Con) continued to exhibit similar body weights as the Controls (Figure 1A). In addition, Control newborns nursed by HF dams (Con/HF) showed significantly increased body weight (Figure 1A). This pattern was maintained when offspring were weaned to post-weaning high fat diet with all groups showing increased body weights as compared to the respective offspring weaned to a normal fat diet (Figure 1A).

All offspring that were exposed to maternal high fat diet had significantly increased percentages of body fat when compared with Controls, regardless of the timing of high fat diet exposure (pregnancy and/or lactation; Figure 1B).

Blood Pressure

At 6 months of age irrespective of body weight and regardless of the timing of exposure to maternal high fat diet, all HF groups weaned to normal fat diet showed significantly increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure as compared to the Controls (Figure 2A and B). As stated in methods, we were unable to measure blood pressure of offspring weaned to high fat diet.

Figure 2. Body weights, percentage body fat, systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

Data are mean ± SE for A) body weight (g) and B) increment in body fat percentage versus Con/Con (represented by 100%), C) systolic blood pressure (mmHg) and D) diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) at 6 months of age in offspring exposed to maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and lactation (HF/HF; n = 6), during pregnancy only (HF/Con; n = 6 ) and during lactation only (Con/HF; n = 6). Black bars represent offspring weaned onto a control diet. Grey bars represent offspring weaned onto a high fat diet. *P<0.05 compared to Con/Con animals. #P<0.05 compared with control weaning diet within the same experimental group; one way and two way ANOVA, as appropriate.

Adipose Protein Expression of AGT

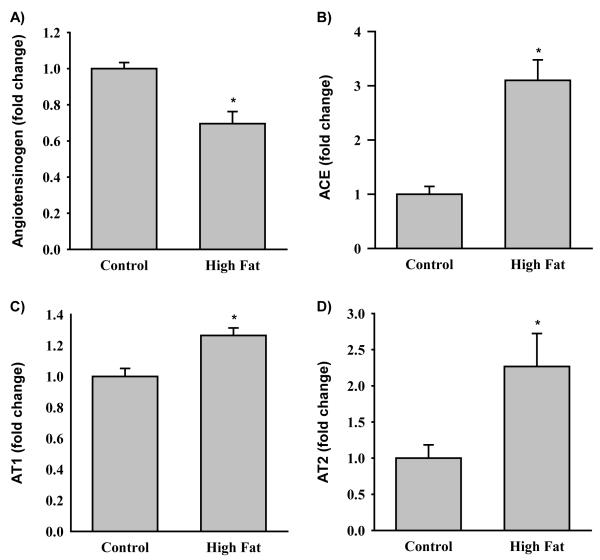

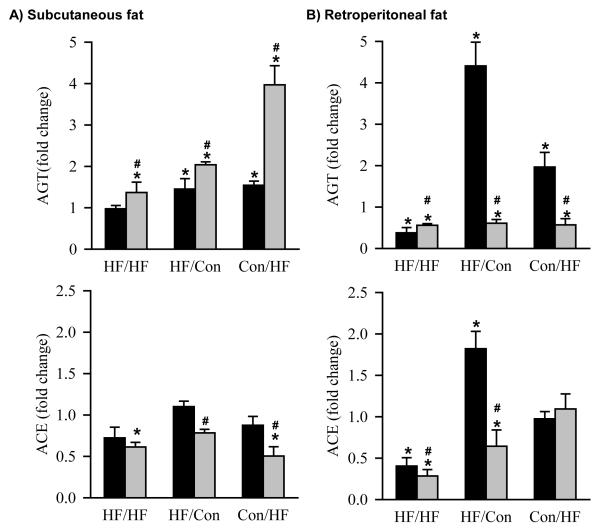

At 1 day of age, HF newborns had significantly decreased protein expression of subcutaneous adipose AGT (Figure 3A). At 6 months of age, HF offspring showed differential protein expression of AGT dependent upon the timing of exposure to the maternal high fat diet and the composition of the post-weaning diet. When HF/HF offspring were weaned to a control diet, AGT protein expression was comparable to Con/Con animals in subcutaneous adipose tissue, though decreased in retroperitoneal adipose tissue (Figure 4A and B). In contrast, HF/Con and Con/HF offspring weaned onto a control diet had markedly increased AGT in both subcutaneous and retroperitoneal adipose tissue (Figure 4A and B). When weaned onto a high fat diet, AGT protein expression was significantly increased in subcutaneous and decreased in retroperitoneal adipose in all HF groups as compared to the Con/Con group (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 3. RAS in offspring at 1 day of postnatal age.

Protein expression of A) angiotensinogen (AGT), B) angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), C) the angiotensin type I (AT1) receptor and D) angiotensin type 2 (AT2) receptor by Western Blotting in subcutaneous fat of offspring of control (Con; n = 6) and high fat diet (HF; n = 6) dams at 1 day of postnatal life. *P<0.05 versus Con animals, Students’ t-test.

Figure 4. AGT and ACE protein expression at 6 months of age.

Protein expression of angiotensinogen (AGT) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) by Western Blotting in A) subcutaneous and B) retroperitoneal fat of offspring exposed to maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and lactation (HF/HF; n = 6), during pregnancy only (HF/Con; n = 6) and during lactation only (Con/HF; n = 6). Black bars represent offspring weaned onto a control diet. Grey bars represent offspring weaned onto a high fat diet. *P<0.05 compared to control (Con/Con) animals, represented by a fold change of 1 (dotted line). #P<0.05 compared with normal diet within the same experimental group, two way ANOVA.

Adipose Protein Expression of ACE

At 1 day of age, HF newborns had significantly increased protein expression of subcutaneous adipose ACE (Figure 3B). At 6 months of age, when HF/HF offspring were weaned onto a control diet, the changes in the protein expression of ACE were similar to the changes in AGT, that is, ACE expression was comparable to Con/Con in subcutaneous adipose and decreased relative to Con/Con in retroperitoneal adipose tissue (Figure 4A and B). In contrast, when HF/Con and Con/HF males were weaned onto a control diet, the subcutaneous adipose ACE protein expression was unchanged, despite elevated subcutaneous adipose tissue AGT in these animals. Retroperitoneal adipose ACE expression was significantly increased in HF/Con weaned onto a control diet (Figure 4A and B) . In contrast, subcutaneous and retroperitoneal adipose ACE expression was significantly decreased in all HF groups that were weaned to a high fat diet, except for Con/HF animals in which the retroperitoneal adipose tissue ACE expression levels were not different to the Con/Con group (Figure 4A and B).

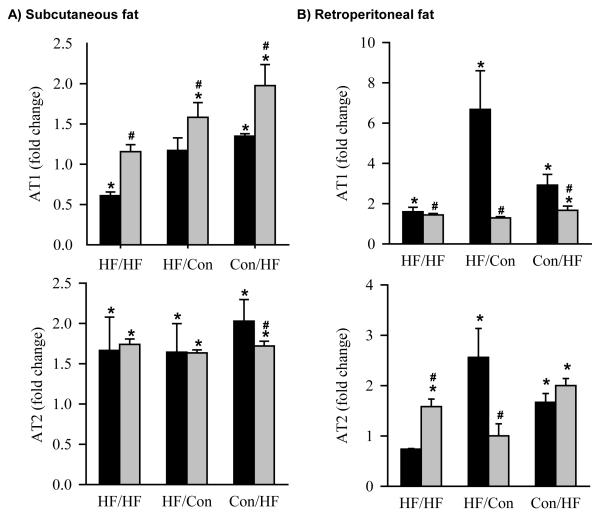

Adipose Protein Expression of the AT1 and AT2 Receptors

At 1 day of age, HF newborns had significantly increased protein expression of subcutaneous adipose vasoreceptor AT1 and proliferative receptor AT2 (Figure 3C and D). At 6 months of age, subcutaneous adipose tissue, AT1 receptor expression was decreased (HF/HF), unchanged (HF/Con) or increased (Con/HF), and AT2 receptor expression was significantly increased in all HF groups when offspring were weaned onto a control diet (Figure 5A). In retroperitoneal adipose tissue AT1 receptor expression was increased in all HF groups weaned onto a control diet (Figure 5B). Conversely, while AT2 receptor expression was increased in HF/Con and Con/HF groups, it was decreased in HF/HF offspring weaned onto a control diet (Figure 5B). When offspring were weaned onto a high fat diet, the protein expression of the AT1 receptor in subcutaneous adipose tissue was significantly increased in the Con/HF and the HF/Con groups and AT2 receptor expression was significantly increased in all HF groups (Figure 5A). In retroperitoneal adipose tissue, the protein expression of the AT1 receptor was significantly increased in the Con/HF group and AT2 receptor expression was increased in HF/HF and Con/HF, but not HF/Con animals weaned onto a high fat diet (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. AT1 and AT2 protein expression at 6 months of age.

Protein expression of the angiotensin type I (AT1) receptor and angiotensin type 2 (AT2) receptor by Western Blotting in A) subcutaneous and B) retroperitoneal fat of offspring exposed to maternal obesity during pregnancy and lactation (HF/HF; n = 6), during pregnancy only (HF/Con; n = 6) and during lactation only (Con/HF; n = 6). Black bars represent offspring weaned onto a control diet. Grey bars represent offspring weaned onto a high fat diet. *P<0.05 compared to control animals (Con/Con), represented by a fold change of 1 (dotted line). #P<0.05 compared with normal diet within the same experimental group; two way ANOVA.

Comment

In the present study in rats, we investigated the influence of a maternal high fat diet during pregnancy, and/or lactation, on the expression of RAS components in two fat types: visceral and non-visceral adipose tissue. We further evaluated the additive effects of a high fat post-weaning diet. The principal findings of our study demonstrate that the male rat offspring exposed to a maternal high fat diet have: (1) increased adiposity and blood pressure regardless of the period of exposure to the high fat diet; (2) persistent and differential impact on adipose RAS components dependent upon the period of exposure to the high fat diet; (3) additional effects on the expression of RAS components induced by a postnatal high fat diet, and (4) adipose specific changes in subcutaneous and retroperitoneal tissue.

The birthweights of pups born to high fat diet and control fed dams in the present study were similar, consistent with previous animal studies of high fat diets during pregnancy.23 Exposure to maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and lactation, or lactation alone, lead to significantly increased body weights and adiposity in rat offspring weaned to a control diet, indicative of programmed obesity in these animals. Although at 6 months of age body weight was not significantly increased in HF/Con offspring, all HF offspring had significantly increased adiposity compared with controls, in agreement with previous studies of maternal high fat diet, in which offspring body weights were a poor surrogate for body composition.23 This is important, since adiposity represents a greater risk factor for the development of cardiovascular and metabolic disease than body weight alone,24 and all HF offspring were hypertensive at 6 months of age.

The mechanism underlying increased adiposity in HF offspring is unknown, but it may reflect the autocrine/paracrine actions of AGT on local adipocytes, since increased AGT is a late marker of adipocyte differentiation in mice and humans.25-28 In mouse and human adipose tissue, AGT has been shown to promote an increase in fat mass by the stimulation of lipogenesis via the AT2 receptor12,29-31 and to have antilipolytic action via the AT1 receptor.31 Accordingly, the protein expression of AGT and AT2 receptor in subcutaneous adipose tissue was increased in offspring that were exposed to a maternal high fat diet during either pregnancy or lactation and independent of postnatal weaning diet in the current study.

AGT was significantly increased in subcutaneous fat of all rat offspring weaned onto a high fat diet, consistent with previous studies that demonstrated up-regulation of adipose tissue AGT mRNA expression by fatty acids in vitro27 and during diet-induced obesity in vivo.33 The mechanism accounting for significantly lower AGT in retroperitoneal fat of offspring weaned onto a high fat diet is unknown, however, in both subcutaneous and retroperitoneal fat pads, similar patterns of AT1 receptor and AGT expression were observed in all the treatment groups. These data are consistent with previous studies in mice, demonstrating that the AT1 receptor is a primary regulator of AGT.34 The most dramatic effect of maternal high fat diet on rat AGT protein expression occurred when a mis-match occurred between the early life nutritional environment experienced by the offspring and the nutrition available at weaning. The significantly up-regulated adipose RAS in rat offspring exposed to maternal high fat diet during pregnancy alone and weaned onto a control diet may tip metabolism in favor of energy storage and, hence, account for increased adiposity in these animals, even in the absence of alterations in body weights at 6 months of age.16

Programmed alterations in the adipose tissue RAS may also have important implications for arterial blood pressure regulation in animals exposed to maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and/or lactation, since plasma AGT is positively correlated with arterial blood pressure in both human and rat models of hypertension.35-39 AGT is expressed in adipose tissue,41 regulated by obesity,41-42 and secreted in the systemic circulation.24,34 Moreover, studies in AGT-deficient mice have shown that adipocyte-specific over-expression of AGT rescues hypotension in these animals.24 It is possible that adipose-derived AGT serves as a substrate for the systemic RAS with subsequent paracrine actions on adipose tissue angiogenesis or effects on local vascular smooth muscle tone, as well as endocrine actions mediating increased total peripheral resistance and arterial blood pressure,32 thereby contributing to programmed increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressures observed in HF rat offspring.

Several studies have implicated kidney development in the early life origins of adult hypertension.43 The RAS is important for normal kidney growth, since fetal AT1 receptor antagonism results in decreased kidney weight in rats44 and sheep45. Moreover, a functioning RAS is required for normal nephrogenesis, since, in rats, perinatal suppression of Ang II or blockade of the AT1 receptor are associated with decreased number of glomeruli, glomerular enlargement and hypertension in adults.46,47 Although renal RAS data were not collected in the present study, altered protein expression of almost all the measured components of the RAS were observed in adipose tissue of HF offspring 1 day postnatally and at 6 months of age. Global alterations in the offspring RAS during early postnatal life may lead to alterations in renal nephrogenesis occurring during the early lactation period, that may contribute to the hypertension observed in this model.

The mechanism accounting for variable changes in ACE expression with age, obesity and postnatal diet are unknown. While tissue-specific regulation of ACE by glucocorticoids has been demonstrated in fetal life,48 few studies have examined regulation of this enzyme in adult animals. Obesity has been shown to lower49 or not change33,41 adipose tissue ACE expression in rats and humans. The tendency for adipose tissue ACE to be decreased in subcutaneous fat in response to postnatal high fat diet in HF rat offspring in the current study may indicate down-regulation in response to increased AGT substrate availability and a defense against further increases in adiposity.

Taken together, these data suggest that a high fat diet during pregnancy and/or lactation is sufficient to induce up-regulation of the rat adipose tissue AGT. Given the current global obesity epidemic and the increasing prevalence of obese women of reproductive age, further mechanistic studies of the programming effects of obesity on local adipose tissue RAS and the long term effects of programmed changes in adipose tissue RAS on adiposity and adult blood pressure regulation are warranted.

Condensation.

Maternal high fat diet during rat pregnancy or lactation upregulated offspring renin angiotensin systemin association with obesity and hypertension. Postweaning high-fat diet suppressed angiotensinogen and AT1 receptor.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Linda Day and Stacy Behare for their technical assistance.

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK081756 and R01HD054751.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This study was presented at the 33rd Annual Clinical Meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, San Francisco, CA, SMFM 2013 Annual Meeting.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012 Jan;(82):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laitinen J, Jääskeläinen A, Hartikainen AL, Sovio U, Vääräsmäki M, Pouta A, Kaakinen M, Järvelin MR. Maternal weight gain during the first half of pregnancy and offspring obesity at 16 years: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2012 May;119(6):716–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pettitt DJ, Baird HR, Aleck KA, Bennett PH, Knowler WC. Excessive obesity in offspring of Pima Indian women with diabetes during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1983 Feb 3;308(5):242–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198302033080502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, Roche AF. Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Sep;76(3):653–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.3.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aneja A, El-Atat F, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Hypertension and obesity. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:169–205. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, Dannenberg AL. Secular blood pressure trends in normotensive persons: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1993 Apr;125(4):1154–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90129-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engeli S, Negrel R, Sharma AM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the adipose tissue renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension. 2000 Jun;35(6):1270–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.6.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim S, Soltani-Bejnood M, Quignard-Boulange A, Massiera F, Teboul M, Ailhaud G, Kim JH, Moustaid-Moussa N, Voy BH. The adipose renin-angiotensin system modulates systemic markers of insulin sensitivity and activates the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;(5):27012. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/27012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassis LA, Saye J, Peach MJ. Location and regulation of rat angiotensinogen messenger RNA. Hypertension. 1988 Jun;11(6 Pt 2):591–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hainault I, Nebout G, Turban S, Ardouin B, Ferré P, Quignard-Boulangé A. Adipose tissue-specific increase in angiotensinogen expression and secretion in the obese (fa/fa) Zucker rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Jan;282(1):E59–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2002.282.1.E59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frederich RC, Jr, Kahn BB, Peach MJ, Flier JS. Tissue-specific nutritional regulation of angiotensinogen in adipose tissue. Hypertension. 1992 Apr;19(4):339–44. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones BH, Standridge MK, Taylor JW, Moustaïd N. Angiotensinogen gene expression in adipose tissue: analysis of obese models and hormonal and nutritional control. Am J Physiol. 1997 Jul;273(1 Pt 2):R236–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.1.R236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engeli S, Gorzelniak K, Kreutz R, Runkel N, Distler A, Sharma AM. Co-expression of renin-angiotensin system genes in human adipose tissue. J Hypertens. 1999 Apr;17(4):555–60. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prat-Larquemin L, Oppert JM, Clément K, Hainault I, Basdevant A, Guy-Grand B, Quignard-Boulangé A. Adipose angiotensinogen secretion, blood pressure, and AGT M235T polymorphism in obese patients. Obes Res. 2004 Mar;12(3):556–61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massiéra F, Bloch-Faure M, Ceiler D, Murakami K, Fukamizu A, Gasc JM, Quignard-Boulange A, Negrel R, Ailhaud G, Seydoux J, Meneton P, Teboul M. Adipose angiotensinogen is involved in adipose tissue growth and blood pressure regulation. FASEB J. 2001 Dec;15(14):2727–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0457fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai M, Beall M, Ross MG. Developmental Origins of Obesity: Programmed Adipogenesis. Curr Diab Rep. 2013 Feb;13(1):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0344-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wlodek ME, Mibus A, Tan A, Siebel AL, Owens JA, Moritz KM. Normal lactational environment restores nephron endowment and prevents hypertension after placental restriction in the rat. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Jun;18(6):1688–96. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jellyman JK, Allen VL, Holdstock NB, Fowden A. Glucocorticoid over-exposure in neonatal life alters pancreatic beta cell function in newborn foals. J Anim Sci. 2013 Jan;91(1):104–10. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai M, Gayle D, Babu J, Ross MG. Programmed obesity in intrauterine growth-restricted newborns: modulation by newborn nutrition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005 Jan;288(1):R91–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00340.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desai M, Han G, Ferelli M, Kallichanda N, Lane RH. Programmed upregulation of adipogenic transcription factors in intrauterine growth-restricted offspring. Reprod Sci. 2007 Oct;15(8):785–96. doi: 10.1177/1933719108318597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armitage JA, Lakasing L, Taylor PD, Balachandran AA, Jensen RI, Dekou V, Ashton N, Nyengaard JR, Poston L. Developmental programming of aortic and renal structure in offspring of rats fed fat-rich diets in pregnancy. J Physiol. 2005 May 15;565(Pt 1):171–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke PS, Naaz A. Role of estrogens in adipocyte development and function. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229:127–135. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ainge H, Thompson C, Ozanne SE, Rooney KB. A systematic review on animal models of maternal high fat feeding and offspring glycaemic control. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011 Mar;35(3):325–35. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massiéra F, Bloch-Faure M, Ceiler D, Murakami K, Fukamizu A, Gasc JM, Quignard-Boulange A, Negrel R, Ailhaud G, Seydoux J, Meneton P, Teboul M. Adipose angiotensinogen is involved in adipose tissue growth and blood pressure regulation. FASEB J. 2001 Dec;15(14):2727–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0457fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saye JA, Cassis LA, Sturgill TW, Lynch KR, Peach MJ. Angiotensinogen gene expression in 3T3-L1 cells. Am J Physiol. 1989 Feb;256(2 Pt 1):C448–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.2.C448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saye J, Lynch KR, Peach MJ. Changes in angiotensinogen messenger RNA in differentiating 3T3-F442A adipocytes. Hypertension. 1990 Jun;15(6 Pt 2):867–71. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safonova I, Aubert J, Negrel R, Ailhaud G. Regulation by fatty acids of angiotensinogen gene expression in preadipose cells. Biochem J. 1997 Feb 15;322(Pt 1):235–9. doi: 10.1042/bj3220235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schling P, Mallow H, Trindl A, Löffler G. Evidence for a local renin angiotensin system in primary cultured human preadipocytes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999 Apr;23(4):336–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darimont C, Vassaux G, Ailhaud G, Negrel R. Differentiation of preadipose cells: paracrine role of prostacyclin upon stimulation of adipose cells by angiotensin-II. Endocrinology. 1994 Nov;135(5):2030–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7956925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saint-Marc P, Kozak LP, Ailhaud G, Darimont C, Negrel R. Angiotensin II as a trophic factor of white adipose tissue: stimulation of adipose cell formation. Endocrinology. 2001 Jan;142(1):487–92. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yvan-Charvet L, Even P, Bloch-Faure M, Guerre-Millo M, Moustaid-Moussa N, Ferre P, Quignard-Boulange A. Deletion of the angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R) reduces adipose cell size and protects from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2005 Apr;54(4):991–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yvan-Charvet L, Quignard-Boulangé A. Role of adipose tissue renin-angiotensin system in metabolic and inflammatory diseases associated with obesity. Kidney Int. 2011 Jan;79(2):162–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boustany CM, Bharadwaj K, Daugherty A, Brown DR, Randall DC, Cassis LA. Activation of the systemic and adipose renin-angiotensin system in rats with diet-induced obesity and hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004 Oct;287(4):R943–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00265.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu H, Boustany-Kari CM, Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II increases adipose angiotensinogen expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007 May;292(5):E1280–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00277.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker WG, Whelton PK, Saito H, Russell RP, Hermann J. Relation between blood pressure and renin, renin substrate, angiotensin II, aldosterone and urinary sodium and potassium in 574 ambulatory subjects. Hypertension. 1979;1:287–291. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.1.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeunemaitre X, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, Lifton RP, Williams CS, Charru A, Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Williams RR, Lalouel JM, Corvol P. Molecular basis of human hypertension: role of angiotensinogen. Cell. 1992;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90275-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caulfield M, Lavender P, Newell-Price J, Kamdar S, Farrall M, Clark AJL. Angiotensinogen in human essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1996;28:1123–1125. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamura K, Umemura S, Nyui N, Yamakawa T, Yamaguchi S, Ishigami T, Tanaka S, Tanimoto K, Takagi N, Sekihara H, Murakami K, Ishii M. Tissue-specific regulation of angiotensinogen gene expression in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1996;27:1216–1223. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.6.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nyui N, Tamura K, Yamaguchi S, Nakamaru M, Ishigami T, Yabana M, Kihara M, Ochiai H, Miyazaki N, Umemura S, Ishii M. Tissue angiotensinogen gene expression induced by lipopolysaccharide in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;30:859–867. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassis LA, Marshall DE, Fettinger MJ, Rosenbluth B, Lodder RA. Mechanisms contributing to ang II regulation of body weight. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E867–E876. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.5.E867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giacchetti G, Faloia E, Sardu C, Mariniello B, Garrapa GGM, Gatti C, Camilloni MA, Mantero F. Different gene expression of the RAS in human subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(suppl 5):S71. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Harmelen V, Reynisdottir S, Bergstedt-Lindqvist S, Elizalde M, Lundkvist I, Arner P. Comparison of AGT mRNA levels in fat tissue from obese, non-obese, hypertensive and normotensive subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(suppl 5):S24. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barker DJ, Bagby SP. Developmental antecedents of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005 Sep;16(9):2537–44. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005020160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tufro-McReddie A, Johns DW, Geary KM, Dagli H, Everett AD, Chevalier RL, Carey RM, Gomez RA. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor: role in renal growth and gene expression during normal development. Am J Physiol. 1994 Jun;266(6 Pt 2):F911–8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.6.F911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forhead AJ, Jellyman JK, Gillham K, Ward JW, Blache D, Fowden AL. Renal growth retardation following angiotensin II type 1 (AT ) receptor antagonism is associated with increased AT receptor protein in fetal sheep. J Endocrinol. 2011 Feb;208(2):137–45. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woods LL, Rasch R. Perinatal ANG II programs adult blood pressure, glomerular number, and renal function in rats. Am J Physiol. 1998 Nov;275(5 Pt 2):R1593–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.5.R1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Nyengaard JR, Rasch R. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatr Res. 2001 Apr;49(4):460–7. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zimmermann H, Gardner DS, Jellyman JK, Fowden AL, Giussani DA, Forhead AJ. Effect of dexamethasone on pulmonary and renal angiotensin-converting enzyme concentration in fetal sheep during late gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Nov;189(5):1467–71. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crandall DL, Gordon G, Herzlinger HE, Saunders BD, Zolotor RC, Cervoni P, Kral JG. Transforming growth factor alpha and atrial natriuretic peptide in white adipose tissue depots in rats. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992 Oct;22(10):676–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]