Abstract

Obese postmenopausal women have increased risk of breast cancers with poorer clinical outcomes than their lean counterparts. However, the mechanisms underlying these associations are poorly understood. Rodent model studies have recently identified a period of vulnerability for mammary cancer promotion, which emerges during weight gain after the loss of ovarian function (surgical ovariectomy; OVX). Thus, a period of transient weight-gain may provide a lifecycle-specific opportunity to prevent or treat postmenopausal breast cancer. We hypothesized that a combination of impaired metabolic regulation in obese animals prior to OVX plus an OVX-induced positive energy imbalance might cooperate to drive tumor growth and progression. To determine if lean and obese rodents differ in their metabolic response to OVX-induced weight gain, and whether this difference affects later mammary tumor metabolism, we performed a nutrient tracer study during the menopausal window of vulnerability. Lean animals preferentially deposited excess nutrients to mammary and peripheral tissues rather than to the adjacent tumors. Conversely, obese animals deposited excess nutrients into the tumors themselves. Notably, tumors from obese animals also displayed increased expression of the progesterone receptor (PR). Elevated PR expression positively correlated with tumor expression of glycolytic and lipogenic enzymes, glucose uptake and proliferation markers. Treatment with the anti-diabetic drug metformin during ovariectomy-induced weight gain caused tumor regression and downregulation of PR expression in tumors. Clinically, expression array analysis of breast tumors from postmenopausal women revealed that PR expression correlated with a similar pattern of metabolic upregulation, supporting the notion that PR+ tumors have enhanced metabolic capacity after menopause. Our findings have potential explanative power in understanding why obese, postmenopausal women display an increased risk of breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity increases incidence, progression, and mortality from breast cancer (1), with the adverse effects of obesity primarily observed in postmenopausal woman (1, 2). After menopause, adipose tissue becomes a significant site for the production of estrogens, which may lead to tumor promotion in obese women. Supporting this assertion some studies indicate that circulating estrogens are higher with increasing weight (3) and obesity generally promotes hormone-dependent tumors (4, 5). A recent study has also shown that adipose tissue aromatase activity increases with adiposity (6). Despite this evidence, local levels of estrogens in breast tissue of postmenopausal women were unaffected by obesity (7). Furthermore, a decrease in both breast cancer risk and mortality was recently reported in postmenopausal women receiving oral estrogens, independent of body mass index (BMI) (8). Thus, while estrogen and obesity clearly interact to influence breast cancer, our understanding of this complex relationship remains incomplete.

Obesity is associated with impaired whole body metabolism, including a decreased ability to quickly clear and store excess calories during periods of overfeeding (9, 10). Weight gain is very common during menopause, in part because loss of ovarian estrogen reduces leptin sensitivity in the hypothalamus, thus promoting overfeeding (11). Unless proactive measures are made to replace the loss of ovarian estrogen, restrict energy intake, and/or increase energy expenditure post-menopause, weight gain ensues (12). Calorie restriction and/or weight loss reportedly reduces tumorigenesis and the mitogenic potential of serum (13-16). Conversely, the overfeeding and weight gain associated with menopause is anticipated to create a host environment rich in circulating excess nutrients (particularly glucose and fatty acids), and growth-factors (insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, epidermal growth factor, and leptin), all of which have been shown to promote tumor cell growth (17). This tumor-promoting humoral milieu is predicted to be exacerbated in obese patients because of the pre-existing impairment in energy metabolism.

We have studied the impact of premenopausal obesity on postmenopausal breast cancer outcomes in an experimental paradigm that merges models of obesity (10, 18, 19), mammary tumorigenesis (20, 21), and menopause (ovariectomy; OVX) (22). In that study, an effect of premenopausal obesity on tumor promotion emerged during the period of rapid, OVX-induced weight gain (23). In the present study, we employed this model and found that premenopausal obesity status and menopause-induced overfeeding influence mammary tumor glucose and fatty acid metabolism, and identified a putative novel role for progesterone receptor(PR) in mediating these effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female Wistar rats (100–125g; 5wks) purchased from Charles River Laboratories were individually housed in metabolic caging at 22–24°C and 12:12h light-dark cycle with free access to water. To induce obesity, rats were maintained on purified high-fat diet (HF 46% kcal fat; Research Diets, RD#D12344). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Obesity and Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Model

Rats were injected with 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea (MNU, 50mg/kg) at 52±1 days of age to induce mammary tumor formation, as previously described (23) MNU was purchased by the NCI Chemical Carcinogen Reference Standards Repository operated under contract by Midwest Research Institute MO (N02-CB-07008). From 10–18 weeks of age, rats were ranked by their rate of weight gain in response to the HF diet. Rats in the top and bottom tertiles of weight gain were classified as obesity-prone (OP) and obesity-resistant (OR), respectively, and matured to produce obese and relatively lean animals. Rats from the middle tertile were removed from the study. Rats were palpated weekly throughout the study to detect tumors, and tumors measured in three dimensions using digital calipers. Fourteen lean and 16 obese tumor-bearing animals entered the OVX phase of the study based on tumor burden. Rats were ovariectomized under isoflurane anesthesia and allowed 4-6 days to recover. At OVX, mammary tumor biopsies were obtained via fine needle aspiration (FNA). Body weight and food intake were monitored weekly before surgery and daily thereafter (18, 22). Body composition was determined at OVX and at sacrifice by quantitative magnetic resonance (qMRI; Echo MRI Whole-Body Composition Analyzer).

Metabolic Monitoring System

During surgical recovery, animals were placed in a metabolic monitoring system (Columbus Instruments) for the remainder of the study. This system includes a multi-chamber indirect calorimeter to estimate energy intake, total energy expenditure, and fuel utilization from measurement of oxygen consumption (vO2), carbon dioxide production (vCO2), and urinary nitrogen (10, 18, 22). We have previously reported a 3-week period of rapid weight gain following OVX (22, 23). To ensure our nutrient tracer study was performed during this weight gain period, but before weight gain plateaued, the tracer study was performed 10.5±0.7 days after recovery.

Dual-tracer protocol

During the final 24-hours of the study, a dual-tracer approach was used to monitor the trafficking of glucose and dietary fats in each animal (10, 24, 25). A 1-14C-oleate/1-14C palmitate tracer was blended with the HF diet to achieve a specific activity of 0.52μCi/kcal of dietary lipid. Animals had ad libitum access to this diet during the 24-hour monitoring period and up to the time of sacrifice. Two hours prior to completion of the study period, each animal received an intraperitoneal injection of 3H-2-deoxyglucose (3H-2DOG, 100μCi) to measure tissue-specific glucose uptake. 14C and 3H content of individual tissues was determined as previously described (10, 24, 25).

Low and High Energy Excess Groups

To dissect the individual contributions of obesity and excess energy to our outcome measurements, the lean and obese groups were sub-classified by mean energy imbalance (intake minus expenditure) during the window of rapid weight gain. Sub-classification was based on each animal's average energy balance during the 48-hour period prior to sacrifice (Fig. 1A-B) and were termed Low (9.3kcal/day excess; n=7 Lean & 7 Obese) and High (26.7kcal/day excess; n= 7 Lean & 9 Obese) Energy Excess.

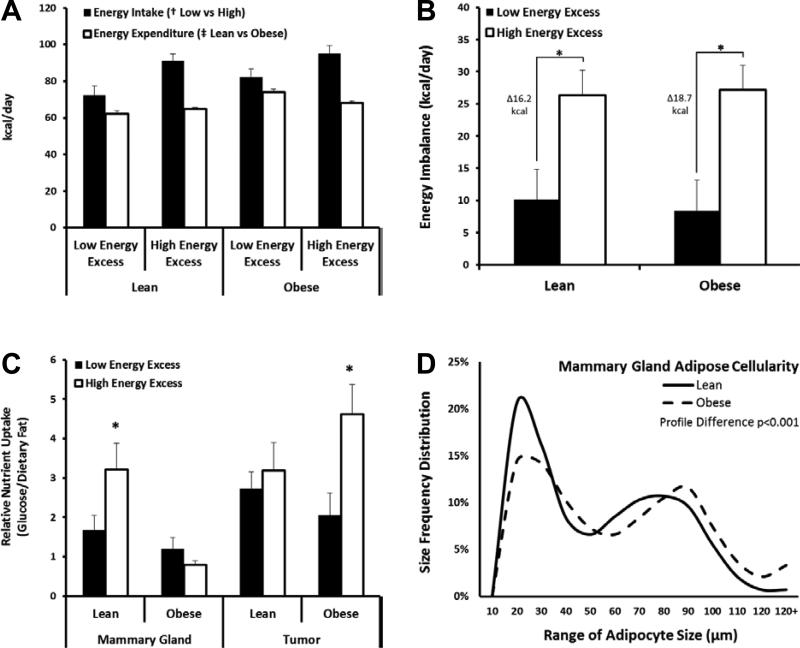

Fig. 1.

Effect of Obesity and Excess Energy on Tissue-Specific Fuel Preference. (A)Energy intake and total energy expenditure and (B)Energy imbalance (intake – expenditure) for Low and High energy excess groups (n=7-9/group). (C)Uptake of glucose (3H-2DOG) relative to retention of dietary fat (14C-oleate/14C-palmitate) in mammary glands and tumors under low (black) and high (white) energy excess conditions (n=59 tumors). (D)Adipocyte size frequency distributions of Lean and Obese mammary adipose tissues. >10,000 cells were isolated from 26 rats for the χ2 analysis. (*p<0.05)

Plasma and Urine Measurements

Tail vein blood was collected on the second diestrus day of the estrous cycle (22) during the week prior to OVX, and post-OVX at sacrifice. All blood draws were made during the latter part of the light cycle, and plasma was isolated and stored at −80°C. Plasma 17β-Estradiol was measured by ELISA (Cayman Chemical). Insulin, leptin, amylin, and glucagon were simultaneously measured using the Rat Endocrine LINCOplex Assay (RENDO-85K; Millipore). Colorimetric assays were used to measure free fatty acids (Wako Chemicals), glucose, triglycerides, and total cholesterol (#TR15421, TR22321, and TR13521, respectively; Thermo-Fisher). Urinary nitrogen was estimated from measurements of urea and creatinine in 24-hour urine collections, as described (18, 19).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

RNA was isolated from pre-OVX tumor FNAs and post-OVX pulverized tumors using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and qPCR was performed as described (26) using primer/probe sets shown in Supplementary Table S1. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo-Fisher). Transcript copy numbers were calculated using the standard curve method (26), and expressed relative to Actin. Targets that amplified below the standard curve were not considered to be expressed.

Targeted PCR Arrays

Genes involved in glucose and fatty acid metabolism were analyzed in end-of-study tumors using pathway-focused PCR arrays (PARN-006 and PARN-007, respectively; SABiosciences) following the manufacturer's instruction. Data were normalized to the mean expression of two housekeeping genes (Rplp1 and Rpl13a) using the comparative Ct method.

Immunohistochemistry and Western Blotting (WB)

Mammary tumors were classified histologically by the criteria of Young and Hallowes (27) and only adenocarcinomas included in subsequent analyses. WB for PR was performed using standard protocols (supplemental methods). Mammary tumors (56 tumors, 2 sections/tumor, 8–10 fields/section) were stained using IHC for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), PR, and Ki-67. Antibodies/conditions are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. ER and PR positivity were scored using Allred scoring, and Ki67 quantification was performed using Aperio analysis software as described (28)

Adipocyte cellularity

At sacrifice, retroperitoneal (RP) and tumor-free inguinal mammary fat pads were removed, weighed, and a portion of each was immediately processed to characterize adipocyte cellularity as described (10)(see supplementary methods).

Metformin Intervention

A separate cohort of obese adult rats entered the OVX phase of the study based on tumor burden, at which time they were randomized to either metformin (2mg/mL in the drinking water; n=11) or control (water only; n=9) groups. Metformin treatment was initiated one week before OVX, and was maintained for study duration. At the time of OVX, mammary tumors were biopsied by FNA. Body weight and tumor volumes were monitored weekly for the duration of the study.

Analysis of Human PR+ Tumors

Seven publically available microarray datasets of human breast cancers (29-35) were analyzed to determine whether PR status correlated with changes in expression of genes comprising specific metabolic pathways in human tumors. Datasets were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). These gene expression profiles are from breast cancer patients that include a range of ages and PR status, as summarized in Supplementary Table S3. Arrays from each dataset were normalized with the robust multichip average (RMA) algorithm (36) and probsets were collapsed to genes by finding the maximum signal for each gene. Each dataset was normalized by mean centering and scaling, and then combined into a single dataset. Because HER2 status was unknown for many tumors, our analysis was restricted to tumors that were ER+ or PR+ to ensure triple-negative (ER−/PR−/HER2−) tumors were excluded. Thus, analysis included ER+/PR+, ER+/PR−, and ER−/PR+ samples. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (37) was performed on this combined dataset using KEGG pathway definitions. All analyses except GSEA were performed in R/Bioconductor.

Statistical analysis

Unless indicated, data were examined with SPSS 18.0 software by ANOVA or χ2 analysis, for nominal and ordinal data, respectively. Relationships between variables were assessed with the Spearman correlation coefficient. Differences and relationships were considered statistically significant when p<0.05. Error bars on all graphs represent standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of tumor-bearing rats prior to OVX

Morphometric and plasma characteristics prior to OVX are shown in Supplementary Table S4. Obese animals weighed 23% more and had 35% higher percent body fat compared to lean animals. Consistent with their increased adiposity, obese animals had significantly higher levels of leptin and triglycerides, and tended to have higher insulin, amylin, glucagon, cholesterol, and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs). Similar to previous work with this model (23), at the time of OVX, the lean and obese groups did not differ in tumor incidence, burden, or mean number of tumors per animal (Supplementary Table S4).

OVX-induced weight gain

As anticipated, OVX significantly increased the rate of weight gain in all animals (2.8 ± 0.5g/day). In addition, the maximum rate of weight gain occurred during the 3-week period following OVX, a window of time that we previously characterized as correlating with maximum energy imbalance (23). As expected, total energy expenditure was significantly higher in obese animals, compared to lean (p<0.05; Fig. 1A), due to higher total body weight. To dissect the individual contributions of obesity and excess energy, the lean and obese groups were sub-classified by mean energy imbalance (intake minus expenditure) during the 48-hour period prior to sacrifice. Differences in energy imbalance between the Low and High Energy Excess groups, however, were due primarily to increased energy intake in the High Energy Excess group (p<0.05; Fig. 1A). As a result, the Lean and Obese High Energy Excess groups experienced an additional 16.2 and 18.7kcal/day excess, respectively, relative to their Low Energy Excess counterparts (Fig. 1B).

Humoral profiles during OVX-induced weight gain

Obesity-associated insulin resistance impairs the body's response to metabolic stress. During OVX-induced weight gain, endocrine factors and metabolites reflective of insulin resistance were measured. Obese animals exhibited higher levels of insulin and amylin, and a trend for higher leptin (Supplementary Table S4). These differences were not affected by the extent of overfeeding (Low vs. High Energy Excess; data not shown) suggesting that the obesogenic state prior to OVX-induced weight gain drives this humoral pattern.

Differential glucose uptake and dietary fat retention in tissues and tumors

We next investigated if adiposity and/or excess energy affected glucose uptake and retention of dietary fat in tumors and peripheral tissues during OVX-induced weight gain. Lean animals showed an increase in glucose uptake in their peripheral tissues (liver, adipose, muscle, and mammary gland) when experiencing a large energy excess (Table 1). In normal, tumor-free inguinal mammary tissue, glucose uptake was over 70% higher in the Lean High Energy Excess group when compared to the Lean Low Energy Excess animals (p<0.05). Increased glucose uptake was also significant in the liver (33%, p<0.05) and trended for skeletal muscle (34%, p=0.13) and retroperitoneal (RP) adipose tissue (39%, p=0.11). Additionally, we saw a similar trend for increased retention of dietary fat in the peripheral tissues from Lean High Energy Excess animals, but these differences did not achieve statistical significance. These data reflect a normal metabolic response to overfeeding, which allows lean animals to clear and store excess nutrients in peripheral tissues. In obese animals, the converse was found. Despite high levels of insulin and excess nutrients, overfeeding did not affect glucose uptake in normal mammary glands, skeletal muscle, liver or RP adipose (Table 1). Dietary fat retention was similarly unaffected by overfeeding in the obese, with the exception of the mammary gland where retention of dietary fat was increased.

Table 1.

Glucose uptake and dietary fat retention in tumors and peripheral tissues during OVX-induced weight gain.

| Lean | Obese | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Energy Excess | High Energy Excess | Low Energy Excess | High Energy Excess | |

| 2-Deoxy-Glucose Uptake (umol/g/min) | ||||

| Tumor | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.04* |

| Mammary Glanda, b, c | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.11* | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| Skeletal Muscle | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.04 |

| Liver | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.02* | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| RP Fat | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Dietary Fat Retention (cal/g/24h) | ||||

| Tumor | 16.52 ± 2.95 | 20.89 ± 5.99 | 26.97 ± 6.63 | 15.05 ± 2.91 |

| Mammary Glandb | 124.53 ± 33.93 | 165.99 ± 20.86 | 94.05 ± 31.41 | 140.53 ± 16.54* |

| Skeletal Muscle | 8.36 ± 0.82 | 9.98 ± 1.07 | 8.50 ± 1.31 | 8.39 ± 0.70 |

| Liver | 106.66 ± 10.51 | 134.44 ± 9.43 | 112.37 ± 8.80 | 109.64 ± 8.39 |

| RP Fat | 196.67 ± 58.68 | 299.03 ± 83.45 | 143.92 ± 22.28 | 162.04 ± 13.94 |

Tumors: n=12-19/group; tissues: n=7-9/group.

p<0.05, Low vs. High Energy Excess.

ANOVA: effect of obesity

energy excess

or their interaction

Nutrient uptake and retention by mammary tumors in these same animals contrasted the normal mammary tissue. In lean animals, increased energy excess did not affect tumor uptake of glucose or dietary fat. However, in obese animals, where normal tissues were generally unresponsive to changes in energy excess, tumor glucose uptake increased by approximately 50% (Table 1), while retention of dietary fat tended to decrease.

The nutrient preference (ratio of glucose uptake to dietary fat retention) of both normal mammary tissue and tumors is shown in Fig. 1C. This comparison emphasizes that, in response to excess energy, mammary tissue in lean animals increases uptake of glucose relative to fat, yet these glands in the obese are unresponsive (Fig.1C, left panels). Conversely, mammary tumors from lean animals do not show a preference for glucose over fat with overfeeding, while those in the obese show a significant glucose preference (Fig. 1C, right panels), characteristic of an “aggressive” metabolic phenotype described as the Warburg effect (38).

Small mammary adipocytes in lean rats may explain increased glucose uptake

Small adipocytes are more responsive to insulin stimulated glucose uptake and inhibition of lipolysis (39). We compared adipocyte size in both lean and obese animals during OVX-induced weight gain. Lean rats had a higher proportion of small adipocytes (<30μm) in their mammary glands, when compared to the obese animals (Fig. 1D). This is consistent with the increased glucose uptake observed in the mammary gland of these animals during overfeeding.

Obesity increases tumor PR expression

Tumor FNAs, obtained immediately prior to OVX, were evaluated for expression of ERα, PR, and HER2, and RNA levels of ERα and HER2 were not different between the lean and obese groups. However, tumors from obese rats had a significantly higher expression of PR than those from the Lean (Fig. 2A). PR expression did not appear estrogen dependent, as expression of classical estrogen responsive genes were not similarly induced (data not shown). These data demonstrate that obesity prior to OVX enhances tumor expression of PR.

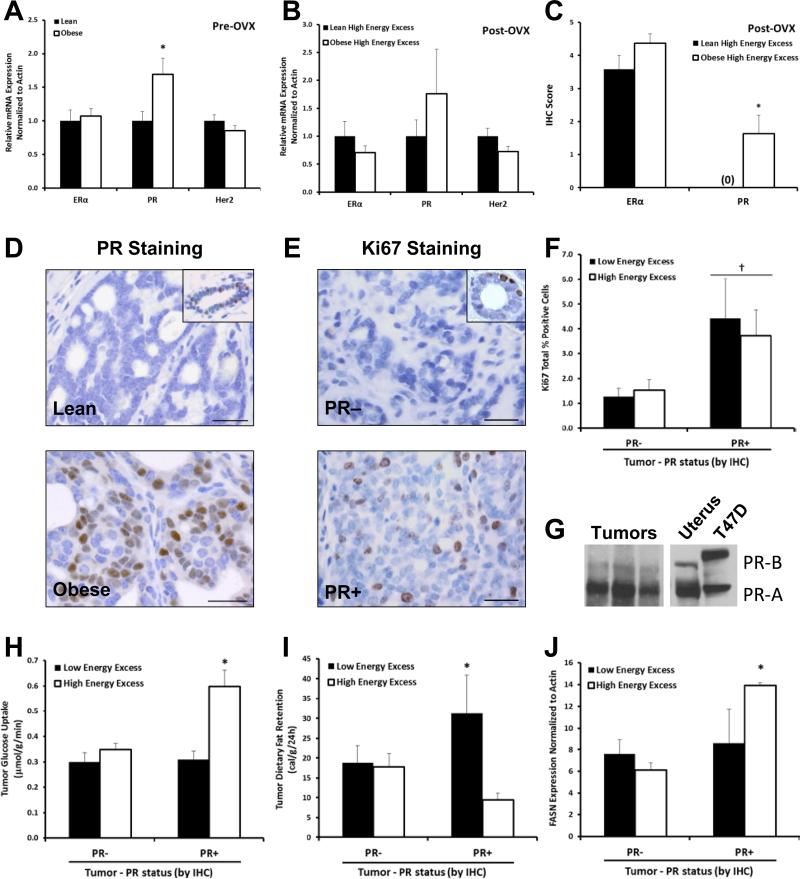

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of tumors. mRNA level of ERα, PR, and Her2 in (A)tumor biopsies taken prior to OVX (n=34 tumors) and (B)tumors during OVX-induced weight gain, under high energy excess conditions (~27kcal/day excess). (C)Levels of ERα and PR in tumors measured with IHC (n=12-19 tumors/group). (D-E)Representative images of PR and Ki67 immunostaining, with insets showing normal duct as positive control; Bar = 25μm.(F)Quantification of Ki67 staining. (G)Representative western blot showing PR−A predominance in mammary tumors; uterus and T47D cells as positive controls. (H-J)Quantification of in vivo uptake of glucose(3H-2DOG) and dietary fat (14C-oleate/14C-palmitate), and FASN expression in PR+ and PR− tumors under low (~9kcal/day excess) or high (~27kcal/day excess) energy excess (n=55 tumors). (*p<0.05)

The expression of ERα, PR, and HER2 was also analyzed at end of study (Fig. 2B). Similar to the pre-OVX expression, PR RNA expression trended and staining by IHC was increased significantly only in the Obese High Energy Excess group compared to the Lean High Energy Excess group, with no differences observed under Low Energy Excess conditions (Fig. 2B-D). WB confirmed PR−A as the dominant isoform present (Fig. 2G).

PR expression correlates with tumor glucose uptake, proliferation, and a glycolytic profile

Having identified tumor PR expression as a distinguishing characteristic of obese animals, we examined the proliferative and metabolic characteristics associated with PR+ tumors based on IHC classification. PR+ tumors had 2.4 times more Ki67 positive cells compared to PR− tumors (Fig. 2E-F, p<0.05), suggesting a higher rate of proliferation in PR+ tumors. PR+ tumors exhibited ~50% increase in glucose uptake and lower retention of dietary fat under High Energy Excess conditions, when compared to PR− tumors (Fig. 2G-H), suggesting a putative role for PR in mediating glucose uptake. Additionally, fatty acid synthase (FASN) expression was higher in the PR+, High Energy Excess tumors (Fig. 2I); in contrast, expression of the fatty acid transporter Slc27a3 was lower in these same tumors (p<0.05; data not shown).

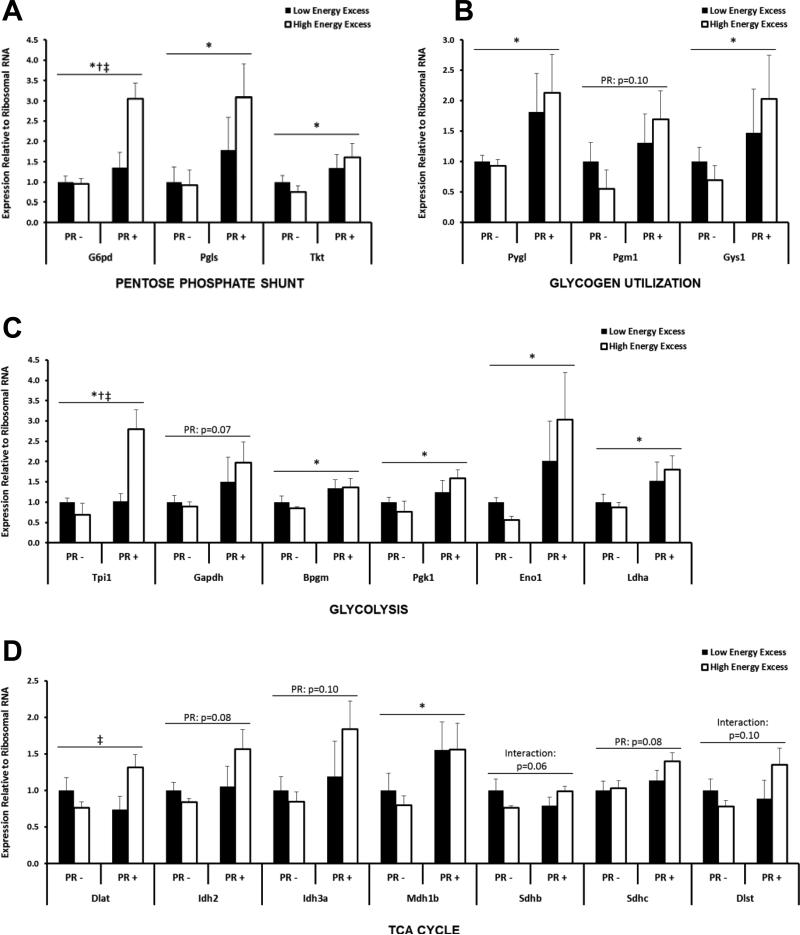

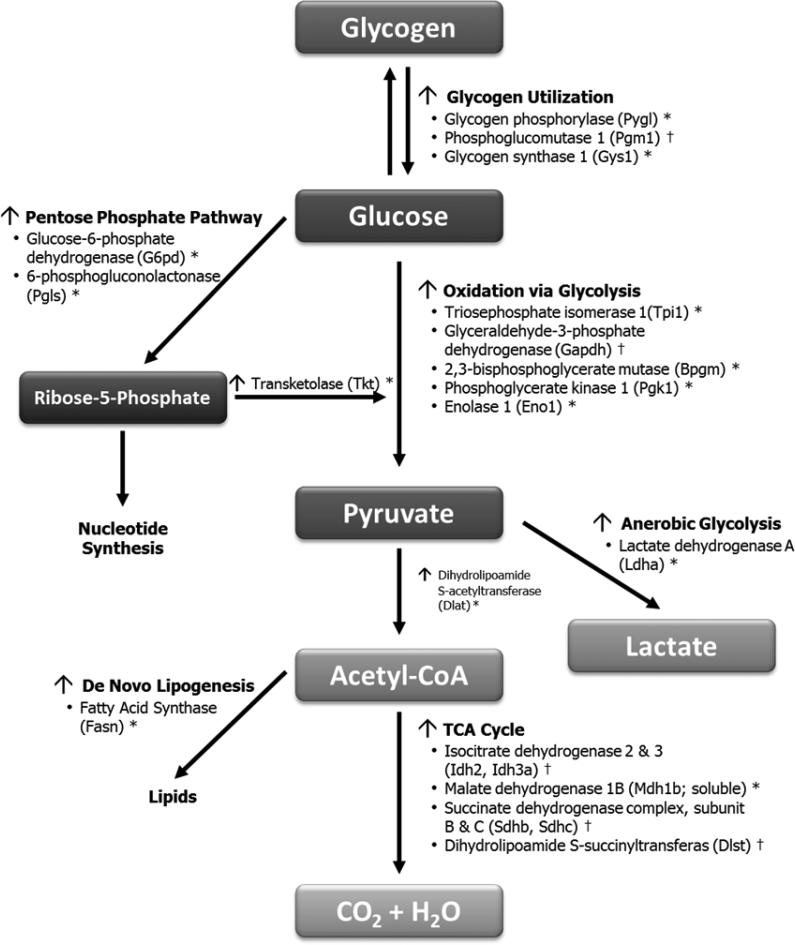

To further understand the relationship between PR and fuel metabolism in tumors, we measured expression of genes involved in glucose and fatty acid metabolism pathways. PR+ tumors exhibited higher expression of genes involved in glycogen utilization (Fig. 3A), the pentose phosphate pathway (Fig. 3B), glycolysis (Fig. 3C), and the TCA cycle (Fig. 3D). Many of these genes were further increased in response to overfeeding. These differences (summarized in Fig. 4) suggest that tumor PR expression is associated with a higher glycolytic capacity, an increased ability to produce energy via the pentose phosphate shunt, and enhanced capacity for de novo lipogenesis, thereby allowing PR+ tumors to use any available fuel source for survival and growth.

Fig. 3.

Expression of metabolism-related genes in tumors at sacrifice. 20 genes were affected by PR (*), Energy Excess (†), or their interaction (‡).including those involved in (A)glycogen utilization, (B)pentose phosphate pathway, (C)glycolysis, and (D)TCA cycle.

Fig. 4.

Summary of changes in PR+ tumors, relative to PR− tumors following OVX-induced weight gain. Data represents significant changes (*p<0.05) and trends († p<0.10) as identified via qPCR or PCR Arrays.

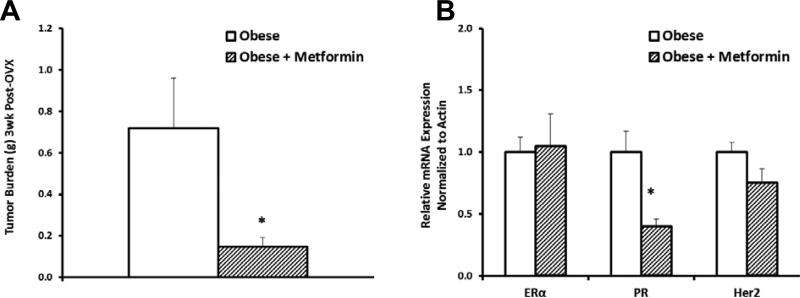

Metformin treatment improves tumor outcomes

Given that tumor uptake of excess nutrients in obese rats was correlated with the inability of peripheral tissues to clear and store excess nutrients, we hypothesized that improving the whole-body metabolic response to overfeeding would decrease tumor burden. To test this hypothesis, obese animals were treated with the commonly used anti-diabetic drug metformin, which improves insulin sensitivity in individuals with type-2 diabetes (40). Tumor burden 3-weeks post-OVX was significantly lower in animals receiving metformin (Fig. 5A). Metformin treatment also significantly lowered tumor PR expression without affecting ERα or HER2 expression (Fig. 5B). Together, these data suggest a potential role for metformin in targeting PR−driven tumor metabolism and reducing tumor burden during OVX-induced weight gain.

Fig. 5.

Effects of metformin on tumors in obese animals. (A)Tumor burden after treatment with metformin for 3 weeks post-OVX. (B)Tumor receptor status after 1week of metformin. (*p<0.05)

Human PR+ tumors have enhanced metabolic capacity

To determine whether the metabolic changes identified in PR+ tumors from our rodent model extended to human breast cancers, we analyzed 7 publicly available microarray datasets of breast tumors (29-35), resulting in a combined 1434 tumors, with 585 cases identified as occurring in postmenopausal women (55–75 years of age; Supplementary Table S3). Patients included in our analysis were diverse with respect to time since menopause, BMI, genetic background, and energy balance under which the tumors were obtained. When compared to PR− tumors, PR+ tumors showed increased expression of genes involved in carbohydrate and protein metabolism, nucleotide synthesis, heme synthesis, ATP production, and cell growth (Table 2). Notably, this enrichment in carbohydrate and protein metabolic genes indicates that PR+ tumors from postmenopausal women have developed the metabolic infrastructure to use any fuel source that becomes available for subsequent energy production and to generate the building blocks required for cell growth/proliferation, thus corroborating our findings in the rat model.

Table 2.

Metabolic pathways enriched in PR+ breast tumors. GSEA of microarrays from human breast tumors (585 tumors from postmenopausal women). KEGG-defined pathways that were enriched(p <0.05) or tended to be enriched(p <0.1) in PR+ tumors vs. PR− tumors, are shown.

| KEGG-defined Pathway | Normalized Enrichment Score | Nominal p-value | Significant in PR+ tumors from all ages | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosome | 2.60 | 0 | * | Protein Metabolism |

| Butanoate Metabolism | 1.88 | 0 | * | Carbohydrate Metabolism |

| Valine Leucine and Isoleucine Degradation | 1.77 | 0 | * | Protein Metabolism |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation | 1.75 | 0 | ATP Production | |

| Parkinsons Disease | 1.64 | 0 | Oxidative Phosphorylation and Mitochondrial Genes | |

| TGF Beta Signaling Pathway | 1.61 | 0 | * | Cell Growth |

| Glycosylphosphatidylinositol GPI Anchor Biosynthesis | 1.68 | 0.008 | * | Carbohyrdate Metabolism (Glycoloysis and Pentose Phosphate Shunt) |

| Propanoate Metabolism | 1.63 | 0.009 | * | Carbohydrate Metabolism |

| Alzheimers Disease | 1.38 | 0.009 | Mitochondrial Genes | |

| Porphyrin and Chlorophyll Metabolism | 1.68 | 0.020 | Heme Synthesis (Electron Carriers for Oxidative Phosphorylation) | |

| ECM Receptor Interaction | 1.45 | 0.026 | * | Metastatic Potential |

| Purine Metabolism | 1.38 | 0.027 | Nucleotide Metabolism | |

| Valine Leucine and Isoleucine Biosynthesis | 1.53 | 0.034 | * | Protein Metabolism |

| Nitrogen Metabolism | 1.45 | 0.053 | * | Protein Metabolism |

| Circadian Rhythm Mammal | 1.54 | 0.056 | Cell Proliferation | |

| Pentose and Glucuronate Interconversions | 1.47 | 0.064 | * | Carbohydrate Metabolism |

| Drug Metabolism Cytochrome P450 | 1.33 | 0.066 | * | Related to Tamoxifen Metabolism |

| Beta Alanine Metabolism | 1.46 | 0.067 | * | Protein Metabolism |

| Peroxisome | 1.30 | 0.068 | * | Membrane Protein Import; Fatty Acid Oxidation; Phospholipid Biosynthesis |

| Pyruvate Metabolism | 1.35 | 0.069 | * | Gluconeogenesis |

| Nucleotide Excision Repair | 1.32 | 0.083 | Nucleotide Metabolism | |

| Ascorbate and Aldarate Metabolism | 1.42 | 0.091 | * | Carbohydrate Metabolism |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the combined effects of obesity and overfeeding on the molecular and metabolic characteristics of tumors after the loss of ovarian function. In lean animals, peripheral tissues, including the mammary gland, respond to a positive energy imbalance with increased uptake of both glucose and fat, while their tumors showed no change in nutrient uptake. In contrast, peripheral tissues from obese animals showed little response in glucose or fat uptake but their tumors exhibited much higher glucose uptake. The impaired metabolic response to excess energy in peripheral tissues of the obese animals was accompanied by higher circulating levels of growth factors and metabolites known to promote tumor survival and growth. In addition, tumors that developed in an obesogenic environment had increased expression of PR prior to OVX that was maintained during the critical window of OVX-induced weight gain. The elevated tumor PR expression was associated with increased glucose uptake, a glycolytic-lipogenic gene expression profile, and higher proliferation. Metformin is associated with increased breast cancer survival in diabetic patients (41) and is known to improve metabolic regulation (40). While causality was not established, a role for PR in enhancing the metabolic capacity of tumors is supported by our findings in both rodents and human tumors. Together, these observations support a dual impact of obesity on postmenopausal tumor promotion by: 1) altering the metabolic and proliferative characteristics of tumors prior to OVX through increased PR expression; and 2) impairing the metabolic response to excess energy in peripheral tissues while enhancing nutrient uptake by tumors. Thus, obesity and overfeeding may converge to enhance tumor survival and growth, despite the loss of ovarian sex hormone production.

We have previously reported that obese rodents experience fluctuations in energy balance over the estrous cycle that are longer in duration and larger in magnitude than those experienced by their lean counterparts (22). This repeated cycle of metabolic extremes, with nutrient excess and deprivation coinciding with low and high levels of estrogen and progesterone, respectively, may elicit adaptations in tumors that make them more flexible to the dramatic environmental changes during menopause. Obesity-induced PR expression in tumors could be one such adaptation. PR is a well-known target of estrogen, raising the possibility that higher levels of estrogens in the obese could be responsible for the PR phenotype of tumors. However, we have found no differences in levels of circulating estrogens between lean and obese animals after OVX in this model (22, 23), and PR expression was observed in the absence of estrogen responsive genes. These data demonstrate that the obesogenic state prior to OVX influences tumor expression of PR, and this increase in PR is sustained during OVX-induced weight gain. Estrogen-independent changes in PR are not without precedent. In normal mammary epithelial cells, PR expression has been demonstrated in ER−negative cells (42). Additionally, IGF has been shown to downregulate PR expression in an ER−independent manner (43). Thus while both our data, and the work of others, support the possibility for estrogen-independent increases in PR in tumors with obesity, local tissue measurements of estrogen that are focused in tumor-bearing glands (44) or stromal vascular subfractions enriched with preadipocytes (45) may provide additional insight into estrogen's role in this effect.

High tumor PR expression, as observed in obese animals with overfeeding, is associated with a glycolytic-lipogenic phenotype typical of aggressive tumors (46, 47). Independent of tumor type, the transformed state is characterized by the ability of tumor cells to consume glucose at a higher rate than normal cells. Much of this glucose is metabolized through glycolysis to lactate, which occurs even under conditions where oxygen concentrations are sufficient to support mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. This attribute of tumors is generally referred to as the “Warburg Effect” (38, 47). Importantly, we show that the association between tumor PR expression and a glycolytic-lipogenic gene expression profile is not limited to our rodent model, as our analysis of clinical tumor datasets demonstrates that PR+ tumors from postmenopausal women also have a gene expression profile consistent with enhanced metabolic flexibility. Data from both the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) and the Nurses’ Health Study further support progesterone and/or PR's role in postmenopausal breast cancer. Postmenopausal women receiving the combination of estrogen and progesterone, but not estrogen alone, have a reported 24% increased risk of invasive breast cancer compared to placebo (48), and PR, but not ER expression, has been independently associated with body mass index (BMI) after menopause (49).

In addition to “priming” the tumor, obesity may also “prime” the body to create an environment conducive to tumor survival and growth during OVX-induced weight gain. Obesity is commonly associated with metabolic dysregulation, reflected by insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, dyslipidemia, and inflammation. Collectively, these factors underlie the metabolically inflexible state associated with obesity (9), in which there is little or no regulatory response to common metabolic challenges (fasting, exercise, insulin infusions). We have also observed this impaired response with obesity during sustained periods of overfeeding (10, 24, 25). The consequence of an impaired response to OVX-induced overfeeding in the present study is that tumors in obese animals would be bathed in high levels of nutrients and growth factors known to promote tumor survival and growth. For example, leptin, which has been shown to activate proliferative pathways and upregulate expression of ERα (reviewed in (17)), has been implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of breast cancer (48, 50). Our data showed an increase in circulating leptin in obese rats prior to OVX, and a trend for higher leptin during OVX-induced weight gain. Similarly, obese animals in this study had higher insulin levels than lean animals, which has also been associated with tumor promotion and increased cancer risk (50). Our observations, however, likely underestimate the tumorigenic potential of serum factors as blood was collected in the latter part of the rats’ light cycle, when food consumption is lowest. Additional studies that obtain hormone, cytokine, and metabolite measurements during the dark cycle, when food consumption is greatest may reveal more profound postprandial differences between lean and obese animals and could speak to the differences in tumor promotion we have reported.

Together with our previous work, these studies provide evidence that obesity promotes breast cancer after menopause in two ways. First, by increasing tumor expression of PR, obesity may make tumors better prepared to adapt to the extreme metabolic state of excess nutrients and loss of sex hormone production during menopause. Second, the impaired metabolic state that is characteristic of obesity decreases the ability for peripheral tissues to respond to an influx of excess energy, effectively providing tumors with greater exposure and/or access to nutrients and circulating factors that facilitate tumor survival and growth. These effects of obesity likely converge during OVX/menopause-induced weight gain to enhance tumor survival and growth, despite the loss of ovarian sex hormone production. The window of menopausal weight gain may, therefore, provide a narrowed window during which insulin sensitizers and other interventions that improve metabolic control could be highly efficacious for the treatment and prevention of postmenopausal breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Drs. J. Higgins and M. Jackman and for intellectual discussions and assistance with tracer studies, and G. Johnson, J. Houser, K. Hedman, A. Lewis, K. P. Bell, and S. Edgerton for technical assistance.

Support:

This work was primarily supported by the Komen Foundation (KG081323; SMA), Cancer League of Colorado (SMA), American Institute for Cancer Research (EDG), and Colorado Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NORC) pilot award (NIH DK048520; EDG).

Additional support was provided by the Department of Defense (BCRP BC098051; EAW), NIH (DK038088; PSM), the Colorado NORC Energy Balance Laboratory and Metabolic Core (NIH DK048520), and the University of Colorado Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core (NIH P30-CA046934).

Footnotes

Authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang Z, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Rosner B, et al. Waist circumference, waist:hip ratio, and risk of breast cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:1316–24. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335:1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poortman J, Thijssen JH, de Waard F. Plasma oestrone, oestradiol and androstenedione levels in post-menopausal women: relation to body weight and height. Maturitas. 1981;3:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(81)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feigelson HS, Patel AV, Teras LR, Gansler T, Thun MJ, Calle EE. Adult weight gain and histopathologic characteristics of breast cancer among postmenopausal women. Cancer. 2006;107:12–21. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sellers TA, Davis J, Cerhan JR, Vierkant RA, Olson JE, Pankratz VS, et al. Interaction of Waist/Hip Ratio and Family History on the Risk of Hormone Receptor-defined Breast Cancer in a Prospective Study of Postmenopausal Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:225–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris PG, Hudis CA, Giri D, Morrow M, Falcone DJ, Zhou XK, et al. Inflammation and increased aromatase expression occur in the breast tissue of obese women with breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1021–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta RR, Valcourt L, Graves J, Green R, Das Gupta TK. Subcellular concentrations of estrone, estradiol, androstenedione and 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17-beta-OH-SDH) activity in malignant and non-malignant human breast tissues. Int J Cancer. 1987;40:305–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910400304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Gass M, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women's Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70075-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storlien L, Oakes ND, Kelley DE. Metabolic flexibility. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:363–8. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackman MR, Steig A, Higgins JA, Johnson GC, Fleming-Elder BK, Bessesen DH, et al. Weight regain after sustained weight reduction is accompanied by suppressed oxidation of dietary fat and adipocyte hyperplasia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1117–29. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00808.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal Hormones Determine Sensitivity to Central Leptin and Insulin. Diabetes. 2006;55:978–87. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gambacciani M, Ciaponi M, Cappagli B, De Simone L, Orlandi R, Genazzani AR. Prospective evaluation of body weight and body fat distribution in early postmenopausal women with and without hormonal replacement therapy. Maturitas. 2001;39:125–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Z, Jiang W, Zacher JH, Neil ES, McGinley JN, Thompson HJ. Effects of energy restriction and wheel running on mammary carcinogenesis and host systemic factors in a rat model. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:414–22. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogozina OP, Bonorden MJ, Seppanen CN, Grande JP, Cleary MP. Effect of chronic and intermittent calorie restriction on serum adiponectin and leptin and mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:568–81. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong KR, Sims AH, Harvie M, Chapman M, Dunn WB, Broadhurst D, et al. Biomarkers of dietary energy restriction in women at increased risk of breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:720–31. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azrad M, Chang PL, Gower BA, Hunter GR, Nagy TR. Reduced mitogenicity of sera following weight loss in premenopausal women. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:916–23. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.594209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ray A, Cleary MP. Obesity and breast cancer: a clinical biochemistry perspective. Clin Biochem. 2012;45:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLean PS, Higgins JA, Johnson GC, Fleming-Elder BK, Peters JC, Hill JO. Metabolic adjustments with the development, treatment, and recurrence of obesity in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R288–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00010.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacLean PS, Higgins JA, Jackman MR, Johnson GC, Fleming-Elder BK, Wyatt HR, et al. Peripheral metabolic responses to prolonged weight reduction that promote rapid, efficient regain in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1577–88. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00810.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schedin PJ, Strange R, Singh M, Kaeck MR, Fontaine SC, Thompson HJ. Treatment with chemopreventive agents, difluoromethylornithine and retinyl acetate, results in altered mammary extracellular matrix. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1787–94. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.8.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson HJ, Adlakha H, Singh M. Effect of carcinogen dose and age at administration on induction of mammary carcinogenesis by 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:1535–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.9.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giles ED, Jackman MR, Johnson GC, Schedin PJ, Houser JL, MacLean PS. Effect of the estrous cycle and surgical ovariectomy on energy balance, fuel utilization, and physical activity in lean and obese female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R1634–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00219.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacLean PS, Giles ED, Johnson GC, McDaniel SM, Fleming-Elder BK, Gilman KA, et al. A surprising link between the energetics of ovariectomy-induced weight gain and mammary tumor progression in obese rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:696–703. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steig AJ, Jackman MR, Giles ED, Higgins JA, Johnson GC, Mahan C, et al. Exercise reduces appetite and traffics excess nutrients away from energetically efficient pathways of lipid deposition during the early stages of weight regain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R656–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00212.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wahlig JL, Bales ES, Jackman MR, Johnson GC, McManaman JL, Maclean PS. Impact of High-Fat Diet and Obesity on Energy Balance and Fuel Utilization During the Metabolic Challenge of Lactation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudolph MC, Wellberg EA, Anderson SM. Adipose-depleted mammary epithelial cells and organoids. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:381–6. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9161-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young S, Hallowes RC. Tumours of the mammary gland. IARC Sci Publ. 1973:31–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyons TR, O'Brien J, Borges VF, Conklin MW, Keely PJ, Eliceiri KW, et al. Postpartum mammary gland involution drives progression of ductal carcinoma in situ through collagen and COX-2. Nat Med. 2011;17:1109–15. doi: 10.1038/nm.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Klijn JG, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, Yang F, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. LANCET. 2005;365:671–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller LD, Smeds J, George J, Vega VB, Vergara L, Ploner A, et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13550–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabatier R, Finetti P, Cervera N, Lambaudie E, Esterni B, Mamessier E, et al. A gene expression signature identifies two prognostic subgroups of basal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:407–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popovici V, Chen W, Gallas BG, Hatzis C, Shi W, Samuelson FW, et al. Effect of training-sample size and classification difficulty on the accuracy of genomic predictors. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R5. doi: 10.1186/bcr2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatzis C, Pusztai L, Valero V, Booser DJ, Esserman L, Lluch A, et al. A genomic predictor of response and survival following taxane-anthracycline chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:1873–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chin K, DeVries S, Fridlyand J, Spellman PT, Roydasgupta R, Kuo WL, et al. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:529–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morimoto C, Tsujita T, Okuda H. Antilipolytic actions of insulin on basal and hormone-induced lipolysis in rat adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:957–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stumvoll M, Nurjhan N, Perriello G, Dailey G, Gerich JE. Metabolic effects of metformin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:550–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, Morgan CL. Mortality After Incident Cancer in People With and Without Type 2 Diabetes: Impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:299–304. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilton HN, Graham JD, Kantimm S, Santucci N, Cloosterman D, Huschtscha LI, et al. Progesterone and estrogen receptors segregate into different cell subpopulations in the normal human breast. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2012;361:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui X, Zhang P, Deng W, Oesterreich S, Lu Y, Mills GB, et al. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Inhibits Progesterone Receptor Expression in Breast Cancer Cells via the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Pathway: Progesterone Receptor as a Potential Indicator of Growth Factor Activity in Breast Cancer. Molecular Endocrinology. 2003;17:575–88. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson ER, Misso M, Hewitt KN, Hill RA, Boon WC, Jones ME, et al. Estrogen--the good, the bad, and the unexpected. Endocrine Reviews. 2005;26:322–30. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price T, Aitken J, Head J, Mahendroo M, Means G, Simpson E. Determination of aromatase cytochrome P450 messenger ribonucleic acid in human breast tissue by competitive polymerase chain reaction amplification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:1247–52. doi: 10.1210/jcem.74.6.1592866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno-Sanchez R, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Marin-Hernandez A, Saavedra E. Energy metabolism in tumor cells. FEBS J. 2007;274:1393–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young CD, Anderson SM. Sugar and fat - that's where it's at: metabolic changes in tumors. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:202. doi: 10.1186/bcr1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu MH, Chou YC, Chou WY, Hsu GC, Chu CH, Yu CP, et al. Circulating levels of leptin, adiposity and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:578–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE. Risk Factors for Breast Cancer According to Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:218–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng Q, Dunlap SM, Zhu J, Downs-Kelly E, Rich J, Hursting SD, et al. Leptin deficiency suppresses MMTV-Wnt-1 mammary tumor growth in obese mice and abrogates tumor initiating cell survival. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:491–503. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.