Abstract

Critical consciousness, the awareness of social oppression, is important to investigate as a buffer against HIV disease progression in HIV-infected African American women in the context of experiences with discrimination. Critical consciousness comprises several dimensions, including social group identification, discontent with distribution of social power, rejection of social system legitimacy, and a collective action orientation. The current study investigated self-reported critical consciousness as a moderator of perceived gender and racial discrimination on HIV viral load and CD4+ cell count in 67 African American HIV-infected women. Higher critical consciousness was found to be related to higher likelihood of having CD4+ counts over 350 and lower likelihood of detectable viral load when perceived racial discrimination was high, as revealed by multiple logistic regressions that controlled for highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence. Multiple linear regressions showed that at higher levels of perceived gender and racial discrimination, women endorsing high critical consciousness had a larger positive difference between nadir CD4+ (lowest pre-HAART) and current CD4+ count than women endorsing low critical consciousness. These findings suggest that raising awareness of social oppression to promote joining with others to enact social change may be an important intervention strategy to improve HIV outcomes in African American HIV-infected women who report experiencing high levels of gender and racial discrimination.

Keywords: Critical consciousness, HIV, African American women, Protective factor, Perceived racial discrimination, Perceived gender discrimination

Introduction

Despite the reduction in AIDS and mortality with the introduction of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), there are still about 50,000 new HIV infections annually and over 1 million people living with HIV in the United States [1]. African American women have one of the highest incidence rates of HIV infection and comprise 35 % of new HIV diagnoses among African Americans and 65 % of new infections among women [2]. HIV/AIDS is also one of the leading causes of death of African American women ages 25–44 [3].

Perceived racial and gender discrimination (PRD and PGD) refer to the awareness of unfair, unequal, or demeaning treatment by others toward the self based on race and gender. Discrimination is rooted in social inequality that gives rise to structural factors such as lack of access to health care, education, and other resources that may contribute to racial HIV health disparities [4]. PRD and PGD have been conceptualized as chronic, everyday stressors that relate to poor health outcomes and behaviors in community samples [5, 6]. Among African Americans, higher PRD has been linked to poor health behaviors such as cigarette smoking [7–9], increased alcohol consumption [10], and lower adherence to physician recommendations [11] as well as to higher depressive symptoms [12] and hypertension [13, 14]. PGD has been consistently associated with poor psychological adjustment [6, 15–17], illicit drug use [18], decreased adherence to mammography recommendations [19], and heavier smoking and binge-drinking [20] in diverse samples of women.

A few studies have examined PRD and PGD in relation to health behaviors and perceived health in communities affected by HIV. Higher PRD was found to significantly relate to lower ART adherence [21], greater depressive, posttraumatic stress, and HIV-related symptoms, and to lower perceived general health and health care satisfaction [22]. Higher PRD in an urban sample of African American men was found to relate to higher risk sex behaviors [23]. Substance use, depressive symptoms, and decreased adherence to medical recommendations associated with PRD and PGD have also been found to relate to higher risk for poor HIV health outcomes, including detectable HIV viral load, lower CD4+ cell count, lower ART adherence, and increased risk of mortality among HIV infected individuals [24–32].

Critical consciousness (CC), the awareness of social oppression that promotes joining with others to enact social change, may be an “antidote” to the effects of social oppression and discrimination [33, 34] and contribute to better health in African American women. CC has been conceptualized as having four dimensions: social group identification, discontent with distribution of social power, rejection of system legitimacy (system-blame), and collective action orientation (belief in working on a collective level for social change versus individual-level action) [35]. Among African Americans, denial of racial inequality, the opposite of CC, was found to relate to victim-blaming attributions for racial inequality, internalized oppression, justification of social roles, and social dominance orientation (a preference for hierarchical, over more egalitarian, social organization) [36]. Further, higher African American ethnic consciousness, defined as recognition of structural inequalities faced by one’s ethnic group, was found to relate to greater system-blame as opposed to self-blame [37]. Accurately understanding the effects of social inequality in maintaining discrimination and oppression, as opposed to attributing its effects to individual characteristics, may protect against the deleterious effects of perceived discrimination.

HIV prevention initiatives in resource-challenged communities have used CC to promote individual and community empowerment and collaboration. For example, the Ukwazana program in Cape Town, South Africa trained men who have sex with men (MSM) to be ambassadors to their local communities to work with MSM in HIV prevention efforts. High CC in the ambassadors was found to be a tool that aided in their ability to engage MSM in local communities. The ambassadors high in CC were able to link broader societal issues, such as homophobia, to consequences for individuals, such as isolation, that contributed to greater sexual risk behaviors. This understanding was instrumental in developing strategies that addressed risk behaviors in the contexts in which they arose (e.g., providing safe spaces for MSM to meet) [38]. Other programs in South Africa, such as the Intervention for Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equality (IMAGE) program, included CC training as part of a larger HIV prevention program for a group of women in a resource-challenged, high HIV risk community and found that at the end of the training women began to critically analyze social and gender norms and explore their relationships to HIV risk [39]. Although CC has been recognized in HIV prevention programming as a powerful tool to promote greater understanding about sexual risk behaviors and to build community alliances to develop appropriate interventions, no work to date has examined CC in HIV-infected individuals in relation to specific HIV health outcomes either internationally or in the United States.

Several studies have examined aspects of CC in relation to health behavior and outcomes in community samples. Feminist consciousness, defined in part as having high gender identification and positive evaluation of women as a group, was found to relate to a higher likelihood of never having smoked cigarettes in a predominantly white sample of women [40]. In addition, ex-smokers endorsed a more critical perspective about sexist advertising than did current smokers. College-educated African American men who experienced “goal-striving stress,” discrepancies between aspirations and achievement, and who attributed their lack of success to system biases reported lower psychological distress than did men who made attributions to individual factors [41]. Further, data from the National Survey of Black Americans, a study of over 2,000 participants ages 18 and older from urban and rural areas, showed that Black Americans who perceived higher levels of racism and had a greater system-blaming orientation were less likely to die in the 13-year follow-up period compared to African Americans who reported low levels of exposure to racism and had a greater self-blaming orientation [42].

In the current study we investigated (1) the relationships among PRD, PGD, CC and HIV disease markers (detectable versus undetectable viral load; CD4+ cell counts [CD4] at a cutoff of 350 cells/μL, as an indicator for the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [43]; and the difference between nadir, defined as the lowest CD4 prior to initiation of HAART, and current CD4) and (2) CC as a moderator of the associations between PGD and PRD with HIV disease markers in African American women with HIV. We hypothesized that (1) higher PRD and PGD would relate to markers of greater HIV disease progression or severity; (2) higher CC would be associated with markers of slower HIV disease progression and lower severity; and (3) higher CC would significantly moderate the associations of PGD and PRD with markers of HIV disease progression, such that having higher CC at higher levels of perceived discrimination would be protective in that it would relate to better HIV outcomes than having lower CC.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Study participants were recruited from the CORE Center site of the Chicago Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), an ongoing longitudinal multi-center cohort study of HIV-infected and demographically-matched uninfected women enrolled during either 1994–95 or 2001–02. Characteristics of the national WIHS cohort have been published previously [44, 45]. Sixty-seven HIV-infected African American women enrolled in the current study during a WIHS semi-annual visit between 10/1/09 and 3/31/10. Nearly half of the participants in the current sample were enrolled during the first enrollment wave (1994–95). The current sample was characteristically similar to the larger African American Chicago cohort in terms of age, education, income, marital status, CD4, and viral load. Those who were excluded due to missing partial data (n = 6) were similar to the final sample in terms of age, education, income, employment, marital status, and CD4, but had higher viral load.

Participants complete a detailed, structured interview, brief physical and gynecologic examination, and specimen collection semi-annually. Trained research staff collected self-report data about general and HIV health history, HAART use and adherence, and for the current study, PRD and PGD and CC. The measures of perceived discrimination and CC were adapted from standard measures in the literature [35, 40, 46]. To increase cultural sensitivity and relevance, the measures were pilot tested with WIHS staff, investigators, and members of the Chicago WIHS Community Advisory Board and adapted based on their feedback. Discrimination and CC measures were read aloud to participants, as per standard WIHS procedures. The Institutional Review Board of each institution involved and the WIHS Executive Committee approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Covariates

Demographic characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics for this analysis were drawn from visit 31 or if data from that visit were not available, from the visit closest in time to that visit. Age was calculated from date of birth and used as a continuous measure. Education categories were: completion of grades 1–6, 7–11, high school, and some or all of college. The three categories of income were: less than $6,000; $6,001 to $12,000; and $12,001 or more. Employment was dichotomized.

HAART adherence

Participants estimated the percentage of time they took their HAART medications as prescribed during the 6 months prior to the current study visit. Responses were coded with five categories: 1 = 100 %, 2 = 95–99 %, 3 = 75–94 %, 4 = <75 %, 5 = 0 %. A 95 % HAART adherence rate has been found to significantly inhibit HIV viral replication [47]. Thus, we created a categorical variable for ≥95 % medication adherence versus <95 %; the latter group included 10 participants who reported that they had not been on HAART medications in the past 6 months even though it was medically indicated by CD4 count.

Predictors

Perceived racial and gender discrimination

PRD and PGD were assessed with a modified Detroit Area Study-Discrimination Scale (DAS-DQ; [46]), providing the frequency of perceived general discrimination in day-to-day life. The original nine DAS-DQ items ask about lifetime experiences with discrimination (e.g., “People act as if you are not as good as they are”), rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = never/less than once a year to 5 = almost everyday). The DAS-DQ has shown high levels of internal consistency [46, 48] and convergent and divergent validity [49] in samples of African American men and women and has excellent predictive validity for symptoms of depression and anxiety, environmental mastery, and coronary artery calcification [48, 50, 51].

The current study assessed PRD and PGD with 12 items for each type of discrimination. After each general perceived discrimination item, as described above, a question measuring PRD on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = nothing to 5 = everything) was asked: “How much do you think your race had to do with this?” Another question assessing PGD on a 5-point Likert-type scale was also asked: “How much do you think your gender had to do with this?” Three additional items per type of discrimination asked questions about PRD and PGD more directly and included, for example, “How often do people treat you unfairly because of your gender?” and “How often do people treat you unfairly because of your race?” Mean scores were calculated across relevant items for PRD and PGD. Higher scores reflected higher PRD and PGD. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.93 for PRD and 0.88 for PGD.

Critical consciousness

Twenty-four items were developed for the present study that assessed CC based on Gurin et al.’s [35] four-dimensional theoretical model of identification, power discontent, rejection of system legitimacy, and collective action orientation. Identification was measured with two items, adapted from Zucker, Stewart, Pomerleau, and Boyd’s item assessing group identification [40], and included identification with women and African Americans, rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (e.g., “How much do you identify with other women/African Americans? In other words, how much do you think you have in common with women/African Americans?”). Items assessing the remaining three dimensions were modified from those used in Gurin et al. [35] to apply to contexts relevant to our sample of African American women with and at risk for HIV. Power discontent was measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale asking about whether each of six social groups (i.e., men, women, rich people, poor people, African/Black Americans, people of other races) had 1 = too little to 5 = too much power. Scores for women, poor people, and African/Black Americans were reversed such that higher scores indicated greater power discontent. Rejection of system legitimacy was measured with four pairs of opposing statements each answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale, representing emphases on structural inequities versus individual culpability (e.g., “African/Black American women get HIV because they are irresponsible” versus “African/Black American women get HIV for a number of reasons, including less access to healthcare information and other resources and a higher rate of HIV in the community”). Individual culpability scores were reverse-coded so that higher scores on the four question pairs reflected greater rejection of system legitimacy. Collective action orientation was measured by asking participants to rank order six activities in order of preference for how they might engage in action to promote social change on behalf of women and on behalf of African Americans. Three options were individually-oriented (e.g., voting) and three were collectively-oriented (e.g., participating in rallies). Only the collective action orientation rankings were used in the total score. Two items were added to assess the extent to which participants believed that social change was necessary for women and for African Americans: “How much do you think that political and social change is necessary for women of all races (e.g., black, white, Latina, Asian, etc.)?” and “How much do you think that political and social change is necessary for African/Black American men and women?” A total CC score was calculated by standardizing individual items so that all were on the same metric prior to summing for a total score. Collective action orientation ranked scores were excluded from the calculation of internal consistency of the scale because by nature they would not be consistent with other items. The Cronbach’s alpha for the relevant 18 items was 0.70.

Outcomes

HIV disease markers

CD4+ cells/mm3 were determined by immunofluorescence using flow cytometry performed in AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) certified laboratories. CD4 was dichotomized at the cutoff of <350, which indicates a marker of HIV disease. The change between nadir and the current CD4 was also calculated and analyzed, with a greater positive difference indicating better HIV health. HIV-1 RNA viral load was measured by an isothermal nucleic acid sequence-based amplification method with a lower limit of detection at 48 in laboratories participating in the National Institutes of Health Viral Quality Assurance Program. HIV viral load was dichotomized as detectable (≥50 copies/ml) or undetectable (<50 copies/ml) for the present analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Pearson correlations were used to examine relationships among demographic, HAART adherence, enrollment wave, predictor, and outcome variables. Multiple regression analyses were used to examine CC as a moderator of relationships between PRD and PGD with HIV health markers. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with an alpha level of 0.05. All data analyses used SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, Inc., Chicago IL).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The mean age of participants was 45.96 years (SD = 8.93). The sample was low-income, with the majority (69 %) reporting an annual income of below $12,000 and unemployment (>80 %). Forty-eight percent of the participants completed junior or partial high school and an additional 27 % completed high school. Median CD4 was 425, median nadir CD4 was 330 with counts ranging from 21 to 802, and 65 % of women were HAART adherent 95 % or more of the time. Ninety-five and one-half percent of participants reported HAART initiation 4 or more years prior to the current visit while three participants (4.5 %) reported that their last visit prior to initiating HAART was 6 months earlier. Independent sample t test results for difference in current CD4 cell count, t (65) = 0.10, p = 0.92, and nadir CD4 count, t (65) = −0.11, p = 0.91, between the three participants who reported that their last visit prior to initiating HAART was 6 months earlier and the other participants were not significant.

Means for PGD and PRD were 1.99 (SD = 0.80, minimum = 1/maximum = 4.17) and 2.20 (SD = 0.98, minimum = 1/maximum = 4.42), respectively. Eighty-five percent of participants reported at least some perceptions of discrimination “a few times a year;” 87.3 % attributed at least some of the perceived discrimination to gender and 91.5 % attributed at least some of the perceived discrimination to race (as indicated by scores >1).

Correlations Between Covariates and Outcomes

Enrollment in 1994–95 compared to enrollment in 2001–02 was significantly associated with greater positive CD4 difference from nadir after HAART initiation, r = −0.36, p = 0.003, undetectable viral load, r = 0.32, p = 0.01, higher PGD, r = −0.30, p = 0.01, PRD, r = −0.36, p = 0.003, CC, r = −0.25, p = 0.04, and tended to relate to CD4>350, r = −0.24, p = 0.05 (see Table 1). HAART adherence was significantly associated with greater positive CD4 difference from nadir after HAART initiation, r = 0.30, p = 0.01, undetectable viral load, r = −0.42, p < 0.001, and CD4 >350, r = 0.29, p = 0.02. Age was significantly related to the CD4 difference score, r = 0.29, p = 0.02, PGD, r = 0.31, p = 0.01, and PRD, r = 0.32, p = 0.01, and tended to relate to undetectable viral load, r = −0.23, p = 0.06. Education was significantly correlated with undetectable viral load, r = 0.25, p = 0.046, and higher CC, r = 0.31, p = 0.01. Income was significantly related to undetectable viral load, r = −0.37, p = 0.002, CD4 >350, r = 0.35, p = 0.003, and a greater CD4 difference score, r = 0.36, p = 0.003. Age, education, income, HAART adherence, and enrollment wave were chosen as covariates in subsequent analyses based on their significant correlations with predictor and outcome variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

| Zero-order correlation |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M/n | SD/ % | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Age (m, SD) | 45.96 | 8.93 | – | ||||||||||

| Education (grades 7–11; n, %) |

32 | 47.8 % | 0.22† | – | |||||||||

| Income (≤$12,000/year; n, %) |

46 | 67.6 % | −0.07 | 0.25* | – | ||||||||

| Enrollment wave (1994/95; n, %) |

29 | 43.3 % | −0.46** | −0.15 | −0.22† | – | |||||||

| HAART adherence (<95 %; n, %) |

23 | 34.3 % | 0.28* | 0.13 | 0.22† | −0.12 | – | ||||||

| Detectable viral load (n, %) | 33 | 49 | −0.23† | −0.25* | −0.36** | 0.32** | −0.42*** | – | |||||

| CD4 <350 (n, %) | 25 | 37.3 % | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.35** | −0.24† | 0.29* | −0.66*** | – | ||||

| CD4 difference (M, SD) | 139.15 | 327.70 | 0.29* | 0.02 | 0.36** | −0.36** | 0.30* | −0.48*** | 0.61*** | – | |||

| PGD (M, SD) | 1.99 | 0.80 | 0.31* | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.30* | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.17 | – | ||

| PRD (M, SD) | 2.20 | 0.98 | 0.32** | 0.16 | 0 | −0.36** | 0.14 | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.88*** | – | |

| Critical consciousness (M, SD) |

−0.09 | 7.53 | 0.17 | 0.31* | −0.03 | −0.25* | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.32** | 0.41** | – |

N = 67. PGD perceived gender discrimination, PRD perceived racial discrimination

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

PRD, PGD, CC and HIV Disease Markers

As displayed in Table 1, Pearson correlations showed that PGD, PRD, and CC were not significantly correlated with the changes in CD4 count after HAART initiation, current CD4 <350, detectable viral load or HAART adherence. Multiple regression analyses adjusting for age, baseline-collected education, enrollment wave, income, and HAART did not reveal significant main effects of PGD, PRD, or CC on HIV health markers.

CC as a Moderator of PGD and PRD with HIV Viral Load

Critical consciousness was examined as a moderator of the relationships of PGD and PRD with viral load. Hierarchical logistic regression models were used to test the interactions of PRD × CC and PGD × CC in predicting detectable viral load. Predictors were mean-centered prior to creating interaction terms. The covariates age, education, enrollment wave, income, and HAART adherence were entered in block 1; PGD/PRD was entered in block 2; CC was entered in block 3, and a dummy variable representing the interaction of CC and PGD/PRD (created by multiplying standardized scores on each variable) was entered in block 4.

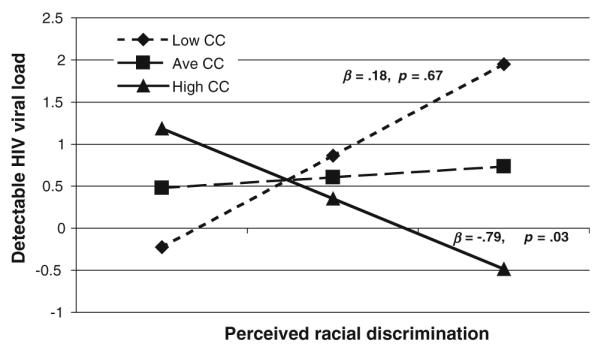

The interaction between CC and PRD was significantly related to detectable versus undetectable viral load, β = −0.13, p = 0.046. The CC and PGD interaction approached significance in predicting detectable versus undetectable viral load, β = −0.11, p = 0.09. Following Holmbeck’s [52] methods for probing significant interaction effects, post hoc regressions were used to compute slopes of the conditional effects of PRD on detectable viral load for participants with high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of CC. As displayed in Fig. 1, at higher levels of PRD, participants with high CC had significantly decreased likelihood of detectable viral load, B = −0.79, p = 0.03, odds ratio = 0.45, while participants endorsing low CC had a non-significant increased likelihood of detectable viral load, B = 0.18, p = 0.67, odds ratio = 1.19.

Fig. 1.

Regression lines for associations between perceived racial discrimination and detectable viral load as moderated by critical consciousness

CC as a Moderator of PGD and PRD with CD4 Cell Count

Critical consciousness was examined as a moderator of the relationships of PGD and PRD with CD4 cell count. Hierarchical multiple linear regressions were performed with the difference between nadir and current CD4, a continuous variable, as the outcome. Hierarchical multiple logistic regressions were performed with the binary variable CD4 <350 as the outcome. With CD4 difference score as the outcome, the covariates age, enrollment wave, income, and ART were entered in block 1; and with CD4 <350 as the outcome, the covariates income, enrollment wave, and ART were entered in block 1. For both outcomes, PGD/PRD was entered in block 2, CC was entered in block 3, and a dummy variable representing the interaction of CC and PGD/PRD was entered in block 4.

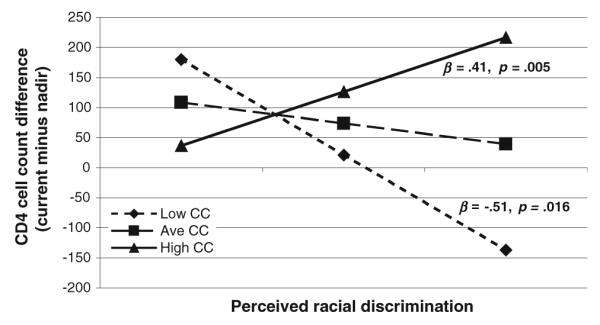

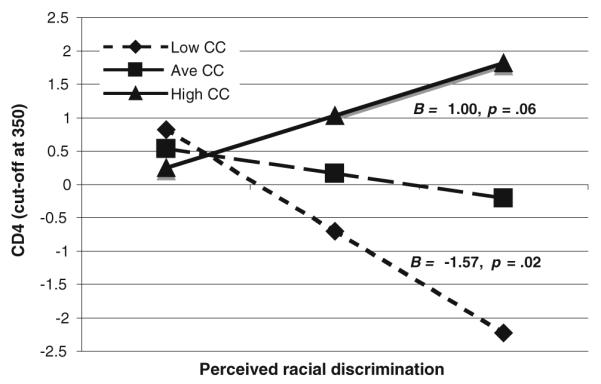

The CC and PRD interaction was significantly associated with the CD4 difference score, β = 0.40, p = 0.002, and CD4 <350, β = 0.16, p = 0.04. Post hoc simple slopes regressions of the conditional effects of PRD on the CD4 difference score and on CD4 <350 with high and low CC were performed. As displayed in Fig. 2, at high levels of PRD, participants endorsing high CC had significantly larger or positive differences in CD4 cell count, β = 0.41, p = 0.01, while participants endorsing low CC had significantly smaller or negative differences in CD4 cell count, β = −0.51, p = 0.02. As displayed in Fig. 3, at high levels of PRD, participants endorsing high CC tended to have a higher likelihood of having a CD4 count over 350, B = 1.00, p = 0.06, odds ratio = 2.72, while participants endorsing low CC had a significantly decreased likelihood of having a CD4 cell count over 350, B = −1.57, p = 0.02, odds ratio = 0.21.

Fig. 2.

Regression lines for associations between perceived racial discrimination and CD4 cell count difference as moderated by critical consciousness

Fig. 3.

Regression lines for associations between perceived racial discrimination and likelihood of CD4 cell counts above 350 as moderated by critical consciousness

The CC and PGD interaction was significantly associated with CD4 difference score, β = 0.39, p = 0.001. Post hoc analyses were also conducted to examine the conditional effects of PGD on CD4 difference score. The pattern of results was similar to that of CC moderating the relationship between PRD and CD4 difference. At high levels of PGD, participants endorsing high CC had significantly larger or positive difference in CD4 cell count, β = 0.42, p = 0.004, while those endorsing low CC tended to have a smaller or negative difference in CD4 cell count, β = −0.32, p = 0.08.

Discussion

The present study was the first to examine CC in relation to perceived discrimination and health outcomes. The results showed that when perceiving high levels of racial and gender discrimination, African American HIV-infected women with high CC were less likely to demonstrate HIV disease progression compared to women with low CC. Specifically, women who perceived high racial discrimination and reported high CC were significantly less likely to have detectable viral load, more likely to have CD4 cell counts above 350, and more likely to have a greater increase in CD4 cell count from their nadir CD4 count, compared to women who reported high PRD and low CC. Women who perceived high gender discrimination and reported high CC had a significantly greater increase in CD4 cell count from their nadir CD4 count compared to women who perceived high gender discrimination and reported low CC. These findings that CC served as a protective factor in HIV-related health in the context of high perceived discrimination contribute to the increasing body of literature that shows that dimensions of CC significantly relate to positive health behavior and outcomes. For example, the National Survey of Black Americans found that higher system blame related to decreased mortality after 13 years [42]; and cross-sectional studies demonstrated that system blame moderated stress and psychological outcomes [41] and that feminist consciousness, a corollary of CC, was related to quitting cigarette smoking or never having smoked [40].

While we did not find direct relationships of PRD and PGD or CC with HIV disease markers, our data are the first to show that when perceptions of discrimination are high, having high CC is related to markers of better HIV-related health. The mechanisms through which CC moderates perceived gender and racial discrimination and CD4 count and viral load, particularly when controlling for HAART, have yet to be elucidated. Factors related to decreased stress and increased self-efficacy through accurate cognitions of the social world and ability to work for social change are important to consider and investigate further.

Critical consciousness may be viewed as a way of coping with stress [53], and the types of strategies used to cope with perceived discrimination have been found to be better predictors of physical health and psychological adjustment than the severity and/or type of discrimination. For example, in a study of discrimination and blood pressure in women, Krieger [13] found that African American women who endorsed taking action in response to unfair treatment or discrimination reported having lower blood pressure than those who endorsed acceptance and “remaining quiet.” African American women who denied any instances of discrimination had a higher risk of hypertension than those who reported at least one instance. In general, use of denial or avoidance as general coping strategies has been linked to greater HIV disease progression [54–56] while active, confrontational coping styles have been found to be related to slower HIV disease progression [57]. These results suggest that the acknowledgement of discrimination and taking action against it, key components of CC, may relieve the burdens of suppressed anger, resentment, fear, shame, anxiety, powerlessness and other emotions that may accompany discrimination. CC is similar to other approach-oriented coping styles that have been found to relate to better physical and HIV-related health.

Critical consciousness involves the acknowledgment of social inequality and its effects on individual behavior. This is in contrast to the denial of inequities or alternatively, to self-blame and blaming individuals for poor conditions in their lives. Among African Americans, greater denial of systemic inequities for different racial groups has been related to higher levels of victim-blaming attributions for racial inequality, internalized oppression, and justification of social roles or social dominance orientation [36]. Accurate externalization of causes of discrimination has been found to relate to lower psychological distress [58]. CC may help to challenge feelings of powerlessness that can lead to psychological distress, negative health behaviors and outcomes. CC allows people to acknowledge racial and gender disparities but to reject the validity of the structural power imbalances that produce and maintain discrimination and stress. Moreover, CC involves not only an awareness of sociopolitical inequality but also the empowerment of individuals to engage in social change [33]. The hope and self-efficacy that can emerge from joining with others for change may have direct influence on immune functioning.

It is noteworthy that the significant moderating relationships of CC on the relationship between discrimination and viral load as well as CD4 levels were direct and not mediated by HAART. Psychoneuroimmunological models posit that psychosocial factors and cognitive appraisals can impact endocrine and immune function that, in turn, may influence viral replication [59]. There is some evidence from randomized controlled trials of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, that shifting negative cognitive attributions and learning effective stress management strategies are associated with improved neuroendocrine regulation and immune status in HIV-infected individuals [60]. Therefore, it is possible that the active and externalized attributions characteristic of CC can interrupt the pathways between chronic stress, poor health behaviors, and disease progression in African American women with HIV and work as an “antidote” [34] to the physiological effects of social oppression. A limitation of the current study is that the small sample size does not provide a definitive understanding of the impact of these factors on immune functioning.

It is also noteworthy that both PRD and PGD were significantly positively correlated with CC. Having higher CC may relate to heightened awareness of discrimination because by definition, CC involves perceptions of system imbalances and their consequences for individual and group experiences [35]. Contrary to expectations, PRD and PGD were not significantly related to HIV disease markers. However, some literature is consistent with this finding. Studies examining relationships of PRD and PGD with psychological outcomes such as depression and distress have shown consistent significant relationships [6, 8], but studies of PRD in relation to physical health indicators have been less consistent, with some studies showing significant relationships between PRD and hypertension [14,61] and others showing no relationship between PRD and hypertension [62, 63].

Many factors could have contributed to the lack of relationships of PRD and PGD with HIV disease in the current study. Perhaps the self-report measure of discrimination was limited in assessing experiences of micro-aggression that may be outside participants’ awareness, with micro-aggression defined as, “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” [64]. In addition, other social-structural factors may be more salient than racial and gender discrimination as perceived stressors for this population, including HIV-related discrimination and stress related to poverty, although research has shown that in HIV-infected men, PRD, but not perceived HIV discrimination, was a significant predictor of ART adherence [30].

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that CC moderated relationships between PRD and PGD and clinically available markers of HIV disease progression. CC may play an important role in promoting HIV health in HIV-infected African American women. Providing opportunities for gathering, discussing, and strategizing for change on individual and community levels would be helpful for promoting CC. Promoting CC can include acknowledging and being open to discussing power imbalances in the system and its effects on those who have relatively more and relatively less power in a provider/client relationship or in a community action group [65], discussing the impact of racism and sexism in women’s lives, and developing individual and group strategies to address these issues. Qualitative studies have shown that intentional development of CC can lead to more critical thinking about factors that impact women’s daily lives [39], and that promotion of CC in samples of MSM can contribute to more appropriate strategies that address issues leading to risky sex behaviors [38]. It has also been suggested that CC is necessary in building collaborations that effectively outreach to those most vulnerable to HIV infection [65]. Our results specifically indicate the importance of implementing interventions for raising CC among women who perceive high levels of racial (and to some extent gender) discrimination as a buffer against poor HIV health. While this paper focused on CC as tool that related to better HIV-related health for women experiencing multiple forms of discrimination within a hierarchical system, it must be emphasized that societal level change is also imperative. CC and group empowerment along with broader social interventions to address racism, sexism, poverty, and their effects are needed to reduce not only acts of discrimination but to address structural inequities.

Acknowledgments

The Chicago site of the Women’s Interagency HIV study (WIHS) collected data for this study. WIHS is funded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Grant 5U01A1034993 (PI: Mardge Cohen, M.D.) and co-funded by National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Drug Abuse. Kathleen Weber is also funded in part by P30- AI 082151. Sannisha Dale is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Research Service Award Grant F31MH095510. These funding sources had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of manuscript. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health. We acknowledge the valuable contributions of Cheryl Watson, Crystal Winston, and Darlene Jointer for their commitment and compassion in their work with WIHS participants, Sally Urwin, Maria Pyra, and Jane Burke-Miller for their tireless help with the data, and of the women of WIHS for their generous dedication to the research.

Contributor Information

Gwendolyn A. Kelso, Department of Psychology, Boston University, 648 Beacon Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA

Mardge H. Cohen, Department of Medicine, Cook County Health and Hospital System and Rush University, 2225 W. Harrison, Suite B, Chicago, IL 60612, USA; The CORE Center/Cook County Health and Hospital Systems and Hektoen Institute of Medicine, Chicago, IL 60612, USA

Kathleen M. Weber, The CORE Center/Cook County Health and Hospital Systems and Hektoen Institute of Medicine, Chicago, IL 60612, USA

Sannisha K. Dale, Department of Psychology, Boston University, 648 Beacon Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA

Ruth C. Cruise, Department of Psychology, Boston University, 648 Beacon Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA

Leslie R. Brody, Department of Psychology, Boston University, 648 Beacon Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Surveillance Report. 2011:21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Prevalence Estimates—United States, 2006. MMWR. 2008;57(39):1073–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics (2011b). Deaths: final data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Report. 2011;60(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman PA, Williams CC, Massaquoi N, Brown M, Logie C. HIV prevention for Black women: structural barriers and opportunities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):829–41. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broman CL, Mavaddat R, Hsu S-Y. The experience and consequences of perceived racial discrimination: a study of African Americans. J Black Psychol. 2000;26(2):165–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Gibbs J, Manning V, Lund M. Physical and psychiatric correlates of gender discrimination: an application of the schedule of sexist events. Psychol Women Q. 1995;19(4):473–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett GG, Wolin KY, Robinson EL, Fowler S, Edwards CL. Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):238–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie BJ, Young AM, Williams DR, Boyd CJ, Kintner EK. African American girls’ smoking habits and day-to-day experiences with racial discrimination. Nurs Res. 2002;51(3):183–90. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broman CL. Perceived discrimination and alcohol use among Black and White college students. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2007;51(1):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Edmondson D, et al. The experience of discrimination and Black-White health disparities in medical care. J Black Psychol. 2009;35(2):180–203. doi: 10.1177/0095798409333585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: a measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. J Black Psychol. 1996;22(2):144–68. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(12):1273–81. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90307-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DR, Neighbors HW. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: evidence and needed research. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(4):800–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greer TM. Coping strategies as moderators of the relationship between race-and gender-based discrimination and psychological symptoms for African American women. J Black Psychol. 2010;37(1):42–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landry LJ, Mercurio AE. Discrimination and women’s mental health: the mediating role of control. Sex Roles. 2009;61(3–4):192–203. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szymanski DM, Stewart D. Racism and sexism as correlates of African American women’s psychological distress. Sex Roles. 2010;63(3–4):226–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ro A, Choi K-H. Effects of gender discrimination and reported stress on drug use among racially/ethnically diverse women in Northern California. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(3):211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dailey AB, Kasl SV, Jones BA. Does gender discrimination impact regular mammography screening? findings from the race differences in screening mammography study. J Womens Health. 2008;17(2):195–206. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zucker AN, Landry LJ. Embodied discrimination: The relation of sexism and distress to women’s drinking and smoking behaviors. Sex Roles. 2007;56(3–4):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boarts JM, Bogart LM, Tabak MA, Armelie AP, Delahanty DL. Relationship of race-, sexual orientation-, and HIV-related discrimination with adherence to HIV treatment: a pilot study. J Behav Med. 2008;31(5):445–51. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bird ST, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. Health-related correlates of perceived discrimination in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.1089/108729104322740884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed E, Santana MC, Bowleg L, Welles SL, Horsburgh C, Raj A. [Accessed December 5, 2012];Experiences of racial discrimination and relation to sexual risk for HIV among a sample of urban African American men. J Urban Health. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9690-x. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11524-012-9690-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Applebaum AJ, Richardson MA, Brady SM, Brief DJ, Keane TM. Gender and other psychosocial factors as predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in adults with comorbid HIV/AIDS, psychiatric and substance-related disorder. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(1):60–5. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chander G, Himelhoch S, Moore RD. Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in HIV-positive patients: epidemiology and impact on antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2006;66(6):769–89. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen MH, French AL, Benning L, et al. Causes of death among women with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Am J Med. 2002;113(2):91–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01169-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen MH, Cook JA, Grey D, et al. Medically eligible women not on highly active antiretroviral therapy: the importance of abuse, drug use and race. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1147–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook JA, Grey DD, Burke-Miller JD, et al. Illicit drug use, depression and their association with highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook JA, Grey DD, Burke-Miller JK, et al. Effects of treated and untreated depressive symptoms on highly active antiretroviral therapy use in a US multi-site cohort of HIV-positive women. AIDS Care. 2006;18(2):93–100. doi: 10.1080/09540120500159284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook RL, Zhu F, Belnap BH, et al. Longitudinal trends in hazardous alcohol consumption among women with human immunodeficiency virus infection, 1995–2006. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(8):1025–32. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner BJ, Laine C, Cosler L, Hauck WW. Relationship of gender, depression, and health care delivery with antiretroviral adherence in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(4):248–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. Seabury Press; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watts RJ, Griffith DM, Abdul-Adil J. Sociopolitical development as an antidote for oppression—theory and action. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27(2):255–71. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurin P, Miller AH, Gurin G. Stratum identification and consciousness. Soc Psychol Q. 1980;43(1):30–47. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neville HA, Coleman MN, Falconer JW, Holmes D. Color-blind racial ideology and psychological false consciousness among African Americans. J Black Psychol. 2005;31(1):27–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown LM, Johnson SD. Ethnic consciousness and its relationship to conservatism and blame among African Americans. J Applied Soc Psychol. 1999;29(12):2465–80. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tucker A, de Swardt G, Struthers H, McIntyre J. [Accessed December 5, 2012];Understanding the needs of township men who have sex with men (MSM) health outreach workers: Exploring the interplay between volunteer training, social capital and critical consciousness. AIDS Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0287-x. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10461-012-0287-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Hatcher A, de Wet J, Bonell CP. Promoting critical consciousness and social mobilization in HIV/AIDS programmes: lessons and curricular tools from a South African intervention. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(3):542–55. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zucker AN, Stewart AJ, Pomerleau CS, Boyd CJ. Resisting gendered smoking pressures: critical consciousness as a correlate of women’s smoking status. Sex Roles. 2005;53(3/4):261–72. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sellers SL, Neighbors HW, Bonham VL. Goal-striving stress and the mental health of college-educated Black American men: the protective effects of system-blame. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(4):507–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaVeist TA, Sellers R, Neighbors HW. Perceived racism and self and system blame attribution: consequences for longevity. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(4):711–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization [Accessed 20 December 2012];Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach. (2010 revision). http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 44.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The women’s interagency HIV study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1013–9. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The women’s interagency HIV study: the WIHS collaborative study group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson J, Anderson N. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, Spencer M. An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Comm Mental Health J. 2006;42:555–70. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor TR, Kamarck TW, Shiffman S. Validation of the Detroit area study discrimination scale in a community sample of older African American adults: the Pittsburgh healthy heart project. Int J Beh Med. 2004;11:88–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keith VM, Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Discriminatory experiences and depressive symptoms among African-American women: do skin tone and mastery matter? Sex Roles. 2010;62:48–59. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9706-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis TT, Everson-Rose SA, Powell LH, et al. Chronic exposure to everyday discrimination and coronary artery calcification in African-American women: the SWAN heart study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:362–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221360.94700.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(1):87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leserman J, Petitto JM, Golden RN, et al. The effects of depression, stressful life events, social support, and coping on the progression of HIV infection. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2(6):495–502. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Antoni MH, Schneiderman N, Esterling B, Ironson G. Stress management and adjustment to HIV-1 infection. Homeost Health Dis. 1994;35(3):149–60. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active anti-retroviral treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):1013–21. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulder CL, Antoni MH, Duivenvoorden HJ, Kauffmann RH, Goodkin K. Active confrontational coping predicts decreased clinical progression over a 1 year period in HIV-infected homosexual men. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(8):957–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: the self-protective properties of stigma. Psychol Review. 1989;96(4):608–30. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cole S. Psychosocial influences on HIV-1 disease progression: neural, endocrine, and virologic mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):562–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181773bbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carrico AW, Antoni MH. Effects of psychological interventions on neuroendocrine hormone regulation and immune status in HIV-positive persons: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):575–84. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817a5d30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA study of young Black and White women and men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(10):1370–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown C, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT, Chang Y. The relation between perceived unfair treatment and blood pressure in a racially/ethnically diverse sample of women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(3):257–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matthews KA, Salomon K, Kenyon K, Zhou F. Unfair treatment, discrimination, and ambulatory blood pressure in Black and White adolescents. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):258–65. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271–86. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Champeau DA, Shaw SM. Power, empowerment and critical consciousness in community collaboration: lessons from an advisory panel for an HIV awareness media campaign for women. Women Health. 2002;36(3):31–50. doi: 10.1300/J013v36n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]