Abstract

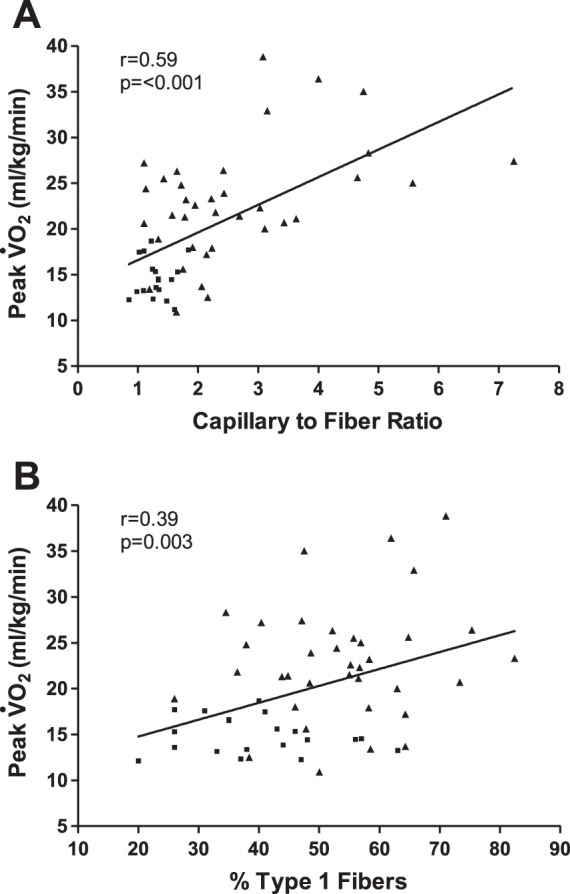

Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF) is the most common form of HF in older persons. The primary chronic symptom in HFPEF is severe exercise intolerance, and its pathophysiology is poorly understood. To determine whether skeletal muscle abnormalities contribute to their severely reduced peak exercise O2 consumption (V̇o2), we examined 22 older HFPEF patients (70 ± 7 yr) compared with 43 age-matched healthy control (HC) subjects using needle biopsy of the vastus lateralis muscle and cardiopulmonary exercise testing to assess muscle fiber type distribution and capillarity and peak V̇o2. In HFPEF versus HC patients, peak V̇o2 (14.7 ± 2.1 vs. 22.9 ± 6.6 ml·kg−1·min−1, P < 0.001) and 6-min walk distance (454 ± 72 vs. 573 ± 71 m, P < 0.001) were reduced. In HFPEF versus HC patients, the percentage of type I fibers (39.0 ± 11.4% vs. 53.7 ± 12.4%, P < 0.001), type I-to-type II fiber ratio (0.72 ± 0.39 vs. 1.36 ± 0.85, P = 0.001), and capillary-to-fiber ratio (1.35 ± 0.32 vs. 2.53 ± 1.37, P = 0.006) were reduced, whereas the percentage of type II fibers was greater (61 ± 11.4% vs. 46.3 ± 12.4%, P < 0.001). In univariate analyses, the percentage of type I fibers (r = 0.39, P = 0.003), type I-to-type II fiber ratio (r = 0.33, P = 0.02), and capillary-to-fiber ratio (r = 0.59, P < 0.0001) were positively related to peak V̇o2. In multivariate analyses, type I fibers and the capillary-to-fiber ratio remained significantly related to peak V̇o2. We conclude that older HFPEF patients have significant abnormalities in skeletal muscle, characterized by a shift in muscle fiber type distribution with reduced type I oxidative muscle fibers and a reduced capillary-to-fiber ratio, and these may contribute to their severe exercise intolerance. This suggests potential new therapeutic targets in this difficult to treat disorder.

Keywords: heart failure, exercise, aging

approximately 50% of heart failure (HF) patients living in the community have preserved left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (HFPEF) (33, 52, 68). HFPEF is nearly exclusively a disorder of older persons and is most common in women. The primary symptom in patients with chronic HFPEF is severe exercise intolerance, measured objectively as decreased peak exercise O2 uptake (peak V̇o2) (2, 3, 5, 26, 30, 34, 35, 41), and this is associated with a reduced quality of life. Despite its importance, the pathophysiology of exercise intolerance in HFPEF is not well understood.

Several lines of evidence suggest that in older HFPEF patients, noncardiac factors may contribute to reduced peak V̇o2 and may be major contributors to the improvement in peak V̇o2 after endurance exercise training (2, 5, 23, 24, 26, 36, 47, 54). It is known that aging results in alterations in skeletal muscle, including a reduction in the relative number of type II fibers (40) and in capillary density (9), and that these are associated with a decline in physical performance (51). Furthermore, it is well established that patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFREF) have multiple skeletal muscle abnormalities (12, 39, 42, 43, 45, 58, 64, 66, 72), including a reduced percentage of type I (oxidative) fibers and a decreased number of capillaries per fiber, and that these contribute significantly to their severe exercise intolerance (49, 64, 65). However, despite the high prevalence of HFPEF and the impact of exercise intolerance as its key chronic symptom, there is no information available regarding skeletal muscle phenotype and its relationship to peak V̇o2 in HFPEF. Therefore, we performed thigh skeletal muscle needle biopsies in HFPEF patients to test the hypothesis that older HFPEF patients, compared with age-matched healthy controls (HC), have reduced type I oxidative fibers and a decreased capillary-to-fiber ratio, which contribute to their exercise intolerance.

METHODS

Participants.

The HFPEF patients in this report are a subset from a previously reported randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the effect of enalapril on exercise capacity (32). This ancillary study for a muscle biopsy before study entry was offered to 40 consecutive participants, with 22 patients agreeing to participate. As previously described in studies from our laboratory (24–26, 32, 35, 37, 60), HFPEF was defined as symptoms and signs of HF according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey HF clinical score of ≥3 and criteria of Rich et al. (56, 59), preserved resting LV systolic function (ejection fraction ≥ 50% and no segmental wall motion abnormalities), and no significant ischemic or valvular heart disease, pulmonary disease, anemia, or other disorder that could explain the patients' symptoms (26, 35, 37). Age-matched, sedentary HC subjects were recruited and screened and excluded if they had any chronic medical illness, were on any chronic medication, had current complaints or an abnormal physical examination (including blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg), had abnormal results on the screening tests (electrocardiogram, cardiopulmonary exercise, and spirometry), or regularly undertook vigorous exercise (23, 62). This protocol was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board for Protection of Human Subjects, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Exercise testing.

As previously described, exercise testing was performed in the upright position on an electronically braked cycle ergometer using a staged protocol starting at 12.5 W for 2 min, increasing to 25 W for 3 min, and with 25 W per 3-min increments thereafter to exhaustion (24, 26, 29, 35, 37, 44, 60). Expired gas analysis was conducted using a commercially available system (CPX-2000 and Ultima, MedGraphics, Minneapolis, MN) that was calibrated before each test with a standard gas of known concentration and volume. Breath-by-breath gas exchange data were measured continuously during exercise and averaged every 15 s, and peak values were averaged from the last two 15-s intervals during peak exercise. A 6-min walk test was performed according to methods previously described by Guyatt et al. (20). The test-retest reliability for 6-min walk distance in our laboratory was good (r = 0.90, P < 0.001).

Skeletal muscle biopsy.

As previously described, skeletal muscle biopsies were performed in the early morning after an overnight fast (51). Subjects were asked to refrain from taking aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other compounds that may affect bleeding, platelets, or bruising for the week before the biopsy and to refrain from any strenuous activity for at least 36 h before the biopsy. Muscle was obtained from the vastus lateralis using the percutaneous needle biopsy technique with a University College Hospital needle under local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine (51). There were no medical complications or other reported adverse events from the procedure.

Visible blood and connective tissue were removed from the muscle specimen, and portions for fiber typing and the capillary-to-fiber ratio were partitioned (51). The muscle portion used for histology analysis was oriented such that the fibers ran longitudinally, were mounted on cork in embedding medium (OCT compound, Miles Laboratory, Naperville, IL), and frozen in isopentane cooled to its freezing point with liquid nitrogen. The muscle portion for capillary density was placed in a histology cassette and quick frozen in isopentane, which was first precooled in liquid nitrogen for 20–30 min. The mounted sample and cassette were stored at −80°C and transported on dry ice to the laboratories of W. E. Kraus at Duke University School of Medicine for processing (51).

Fiber typing.

Fiber type histological analyses were performed following published procedures (16, 19, 51). Monoclonal antibodies against myosin heavy chain were used to identify muscle fiber subtypes. Transverse muscle sections of 10 μm thickness, obtained with a cryostat, were mounted on a glass slide (∼5 sections/slide). Slides were exposed to the primary antibody (Novocastra, Newcastle, Tyne, UK, and Alexis, San Diego, CA) at 1:20 dilution in PBS for 4 h, rinsed in PBS, and exposed for another 4 h in the secondary antibody (FITC-conjugated IgG rabbit anti-mouse, Sigma). Immunostained cross-sections were analyzed using an inverted Axiovert microscope (Zeiss) equipped with fluorescence filters. Images were digitized using a Photometric charge-coupled device camera and Isee software (Inovision, Durham, NC).

Capillary-to-fiber ratio.

Endothelial cells were identified using immunohistochemistry and cell-specific monoclonal (CD31) antibodies (15, 16, 51). CD31 is a mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. AM232-5M, Biogenex) designed for specific localization of the human endothelium. Slides were brought to room temperature and placed in ice-cold acetone for 2 min and PBS for 5 min. Blocking solution (10% horse serum in PBS) was applied for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were applied for 1 h followed by sequential incubation with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG and ABC reagent, according to the manufacturer's specifications (Vectastain ABC, Vector Laboratories). Levamisole was added to block endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity, and immune complexes were localized using the chromogenic alkaline phosphatase substrate Vector red (Vector Laboratories). When counterstained with hematoxolin, dehydrated, and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific), the antigen appears red and nuclei appear blue. Murine IgG monoclonal antibody served as a negative control. The capillary-to-fiber ratio (mean number of capillaries/muscle fiber) was measured by counting endothelial cells and muscle fibers in at least three random ×100 magnification fields per sample (13–15, 31, 51). A minimum of 100 muscle fibers was counted.

Statistical methods.

Descriptive statistics of the participants for the variables of interest are reported as means and SDs for continuous variables and as the number in each category (n) and percentages for categorical variables. Intergroup comparisons of participant characteristics were made by independent-sample t-tests for continuous variables, by Fisher's exact tests for binomial variables, and by χ2-tests for general categorical variables. Comparisons of all outcome measures between groups were made by analysis of covariance, adjusting for sex. Relationships between muscle fiber type and the capillary-to-fiber ratio and peak V̇o2 were assessed by Pearson correlations. Finally, a multivariate regression model was used to assess predictors of peak V̇o2. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was required for significance.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics.

Patients had characteristics typical of chronic HFPEF with New York Heart Association class II–III symptoms, with greater resting systolic blood pressure, abnormal Doppler LV diastolic function, increased LV mass and mass-to-volume ratio, and concentric hypertrophic LV remodeling compared with HC subjects (Table 1). HFPEF patients were clinically stable and New York Heart Association class II (77%) and class III (23%). Chronic systemic hypertension was present in 73% of HFPEF patients. Key characteristics (age, sex, body mass index, and peak V̇o2) did not differ between this subset of HFPEF patients and the larger cohort (32). HFPEF and HC patients were well matched for age, although a greater number of women were in the HC group. Body weight and body surface area were similar between the groups, although body mass index was higher in HFPEF compared with HC patients. The sex and body mass index characteristics of the HFPEF group were consistent with previous reports from large population-based studies (33, 52, 68).

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics

| HFPEF Patients | HC Subjects | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 22 | 43 | |

| Age, yr | 69.8 ± 6.6 | 69.2 ± 7.4 | 0.76 |

| Number of women/men, n (%) | 18/4 (82) | 22/21 (51) | 0.03 |

| Number in the white ethnic group, n (%) | 19 (86) | 41 (95) | 0.33 |

| Height, cm | 163.9 ± 6.7 | 170.7 ± 8.3 | 0.002 |

| Weight, kg | 79.9 ± 15.1 | 78.0 ± 16.9 | 0.67 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.7 ± 5.2 | 26.7 ± 5.1 | 0.03 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.86 ± 0.18 | 1.85 ± 0.36 | 0.90 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 140 ± 22 | 124 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75 ± 9 | 75 ± 7 | 0.92 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 64 ± 6 | 65 ± 7 | 0.67 |

| Left ventricular mass, g | 227 ± 58 | 138 ± 36 | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular mass-to-end-diastolic volume ratio | 3.7 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Lateral mitral annulus velocity, cm/s | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 9.5 ± 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Early mitral flow velocity/lateral mitral annulus velocity | 9.9 ± 2.7 | 7.2 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic filling pattern, n (%) | |||

| Normal | 0 (0) | 33 (77) | <0.001 |

| Impaired relaxation | 18 (82) | 10 (23) | |

| Pseudonormal | 4 (18) | 0 (0) | |

| Restrictive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| B-type natriuretic peptide | 70 ± 46 | 34 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 16 (73) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (14) | ||

| New York Heart Association class, n (%) | |||

| II | 17 (77) | ||

| III | 5 (23) | ||

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Diuretics | 12 (55) | ||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 0 (0) | ||

| β-Blockers | 8 (36) | ||

| Ca2+ channel blockers | 5 (23) |

Values are means ± SD or numbers of patients/subjects per group (n) with percentages.

HFPEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HC, healthy age-matched control.

Exercise performance.

Peak exercise V̇o2, exercise time, workload, CO2 production, and heart rate were significantly reduced in HFPEF versus HC patients (Table 2). Peak exercise systolic and diastolic blood pressures were significantly increased in HFPEF versus HC patients. The peak exercise respiratory exchange ratio was not different in HFPEF versus HC patients, and the mean was ≥1.13 in both groups. Furthermore, the 6-min walk distance was significantly reduced in HFPEF compared with HC patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cardiorespiratory and hemodynamic responses during peak cycle exercise and distance walked in 6 min

| Raw Data |

Adjusted Data* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFPEF patients | HC subjects | HFPEF patients | HC subjects | P Value | |

| Peak exercise | |||||

| Exercise time, min | 9.9 ± 2.6 | 14.8 ± 4.8 | 11.8 ± 0.8 | 14.8 ± 0.6 | 0.004 |

| Workload, W | 73 ± 23 | 116 ± 39 | 89 ± 7 | 115 ± 4 | 0.002 |

| O2 uptake, ml/min | 1192 ± 281 | 1743 ± 530 | 1432 ± 83 | 1734 ± 55 | 0.004 |

| O2 uptake, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 14.7 ± 2.1 | 22.9 ± 6.6 | 16.6 ± 1.2 | 22.8 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| CO2 production, ml/min | 1332 ± 302 | 2016 ± 601 | 1586 ± 97 | 2007 ± 65 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory exchange ratio | 1.13 ± 0.07 | 1.16 ± 0.09 | 1.12 ± 0.02 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 134 ± 16 | 148 ± 16 | 134 ± 4 | 148 ± 3 | 0.004 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 193 ± 24 | 175 ± 23 | 201 ± 5 | 175 ± 3 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 90 ± 8 | 77 ± 7 | 91 ± 2 | 77 ± 1 | <0.001 |

| Ventilatory threshold, ml/min | 696 ± 156 | 929 ± 356 | 817 ± 65 | 925 ± 42 | 0.17 |

| 6-min walk distance, m | 454 ± 72 | 573 ± 71 | 461 ± 17 | 573 ± 11 | <0.001 |

Raw data are presented as means ± SD.

Adjusted for sex and presented as least-square means ± SE. P values correspond to adjusted data.

Skeletal muscle fiber type distribution and capillary-to-fiber ratio.

Compared with HC subjects, older HFPEF patients had a reduced percentage of type I fibers (39.0 ± 11.4% vs. 53.7 ± 12.4%, P < 0.001), a greater percentage of type II fibers (61.0 ± 11.4% vs. 46.3 ± 12.4%, P < 0.001), and a reduced type I-to-type II fiber ratio (0.72 ± 0.39 vs. 1.36 ± 0.85, P = 0.001; Table 3). The capillary-to-fiber ratio was also significantly reduced in HFPEF compared with HC patients (1.35 ± 0.32 vs. 2.53 ± 1.37, P = 0.006; Table 3).

Table 3.

Skeletal muscle fiber type distribution and capillary-to-fiber ratio

| Raw Data |

Adjusted Data* |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFPEF patients | HC subjects | HFPEF patients | HC subjects | ||

| Type I fibers, % | 39.0 ± 11.4 | 53.7 ± 12.4 | 37.4 ± 2.8 | 53.8 ± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Type II fibers, % | 61.0 ± 11.4 | 46.3 ± 12.4 | 62.6 ± 2.8 | 46.2 ± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Type I-to-type II fiber ratio | 0.72 ± 0.39 | 1.36 ± 0.85 | 0.64 ± 0.18 | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Capillary-to-fiber ratio | 1.35 ± 0.32 | 2.53 ± 1.37 | 1.60 ± 0.26 | 2.51 ± 0.17 | 0.006 |

Raw data are presented as means ± SD.

Adjusted for sex and presented as least-square means ± SE. P values correspond to adjusted data.

Relationships between skeletal muscle characteristics and exercise performance.

In univariate analyses with all subjects combined, the capillary-to-fiber ratio (r = 0.59, P < 0.001; Fig. 1A), percentage of type I fibers (r = 0.39, P = 0.003; Fig. 1B), and type I-to-type II fiber ratio (r = 0.33, P = 0.02) were significantly correlated with peak V̇o2 (in ml·kg−1·min−1). Among patient characteristics, the strongest univariate correlants of peak V̇o2 were sex (r = 0.55, P < 0.001) and age (r = −0.31, P = 0.02). In a multivariate model that included the variables of age, sex, body surface area, capillary-to-fiber ratio, and percentage of type I fibers as competing predictors of peak V̇o2, both the capillary-to-fiber ratio (partial r = 0.34, P = 0.02) and percentage of type I fibers (partial r = 0.40, P = 0.004) were independent predictors of peak V̇o2.

Fig. 1.

Relationship of capillary-to-fiber ratio (A) and percentage of type I muscle fibers (B) with peak O2 uptake (V̇o2) in older patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (■) and age-matched healthy control subjects (▲).

Furthermore, in univariate analyses, the capillary-to-fiber ratio (r = 0.48, P < 0.001), percentage of type I fibers (r = 0.35, P = 0.006), sex (r = 0.31, P = 0.01), and age (r = −0.40, P = 0.001) were significantly correlated with 6-min walk distance. In multivariate analyses, the percentage of type I fibers (partial r = 0.28, P = 0.046) remained as a significant, independent predictor of 6-min walk distance.

DISCUSSION

The primary symptom in patients with chronic HFPEF, even when well compensated, is severe exercise intolerance, and it is associated with a reduced quality of life (24, 26, 35); however, its pathophysiology is not well understood. Multiple lines of evidence have suggested that in addition to cardiac function, noncardiac “peripheral” factors are also important contributors to the severe exercise intolerance observed in older HFPEF patients (2, 5, 24, 26, 36, 54). The major novel finding of this study is that compared with HC subjects, older HFPEF patients exhibited a shift in skeletal muscle fiber type distribution with a reduced percentage of slow twitch type I fibers and reduced type I-to-type-II fiber ratio as well as a reduced capillary-to-fiber ratio. Furthermore, both the capillary-to-fiber ratio and percentage of type I fibers were significant, independent predictors of peak V̇o2. The intrastudy comparison with age-matched HC subjects indicated that these abnormalities were in addition to alterations that would be expected from aging alone, and comparisons with reports from others (discussed below) indicate that the abnormalities are similar to those seen in HFREF (12, 39, 42, 43, 45, 58, 64–66, 72). Taken together, these findings may help explain why older HFPEF patients have such severely reduced exercise capacity.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of skeletal muscle fiber composition and capillarity in HFPEF and their relationships with peak V̇o2. However, our results are believable given what is known from many reports regarding skeletal muscle fiber composition and capillarity in patients with HFREF and other populations. Specifically, several investigators have reported that HFREF patients have decreased type I fibers compared with HC subjects (12, 39, 42, 45, 64, 66, 67) and that this is related to peak V̇o2 (49). Moreover, several investigators have reported that the capillary-to-fiber ratio is also reduced in HFREF patients compared with HC subjects (42, 43, 58, 64, 72).

These results build on reports from our group and others (2, 5, 23, 24, 26, 47, 54). We (26) have previously reported that compared with age-matched healthy subjects, older HFPEF patients have a reduced peak exercise arteriovenous O2 difference and that this contributes, along with reduced cardiac output, to their severely reduced peak V̇o2. We also found that noncardiac peripheral factors were a major contributor to the improvement in peak V̇o2 after endurance training (24). In a preliminary analysis, Bhella et al. (2), using 31P magnetic spectroscopy, reported that during static leg exercise, HFPEF patients had impaired skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism compared with HC subjects. Recently, we (23) reported that older HFPEF patients had reduced percent total and leg lean body mass compared with age-matched HC subjects. Moreover, the slope of the relationship of peak V̇o2 with percent leg lean mass was markedly reduced in HFPEF patients versus age-matched HC subjects, suggesting that skeletal muscle hypoperfusion or impaired O2 utilization by the active muscles may play an important role in limiting exercise performance in elderly HFPEF patients. Finally, we (22) recently showed that HFPEF patients have increased thigh intermuscular fat and an intermuscular fat-to-skeletal muscle ratio and that these are related to peak V̇o2. Together with the present report, this suggests that older HFPEF patients have significant skeletal muscle abnormalities and that these may be important contributors to their severely reduced peak V̇o2.

Although not addressed by our study, potential causes for the skeletal muscle abnormalities we observed include neuroendocrine activation, sympathetic overdrive, oxidative stress, inflammation, abnormal Ca2+ cycling and excitation-contraction coupling, and deconditioning (49). Chronic elevations in sympathetic neural activity and decreased nitric oxide bioavailability result in increased vasoconstriction and reduced skeletal muscle blood flow. A consequence of skeletal muscle hypoperfusion is that it leads to the generation of ROS, which is an important stimulus for TNF-α activation, systemic inflammation, and skeletal muscle myopathy (49).

We cannot exclude a potential contribution of physical deconditioning to the skeletal muscle abnormalities we observed in our HFPEF patients. However, multiple studies in animal models and humans have indicated that the skeletal muscle abnormalities found in HFREF patients are not due solely to deconditioning (13, 18, 49, 61, 70). Furthermore, deconditioning primarily decreases type II fibers rather than type I fibers (49).

How might these skeletal muscle alterations contribute to exercise intolerance in older HFPEF patients? V̇o2 kinetics strongly relate to peak exercise capacity (57). In aging and in HF, muscle blood flow (perfusive and diffusive O2 delivery) assumes an important role in limiting V̇o2 kinetics (57). Furthermore, in an animal model, the reduction in maximal V̇o2 resulted primarily from reduced O2 delivery (10). Therefore, the reduced capillary-to-fiber ratio in HFPEF patients would be expected to result in a decreased diffusive capacity for O2 transport to active skeletal muscle during exercise and limit exercise capacity (53). Likewise, increased capillarity and therefore red blood cell volume acts to elevate diffusive O2 conductance and elevate the arteriovenous O2 difference, thus elevating peak V̇o2.

Compared with type II fibers, type I fibers, which we found to be reduced in HFPEF, have greater oxidative capacity and mitochondrial density and contribute disproportionately to the ability to perform sustained aerobic exercise. While speculative, a reduction in the percentage of type I fibers could be associated with reduced oxidative capacity and mitochondrial density and thereby contribute to the reduced peak V̇o2 in HFPEF. Indeed, Coen et al. (8) recently reported that thigh muscle oxidative capacity (measured as maximal stage 3 respiration of permeabilized fibers) is a major determinant of peak V̇o2 in healthy older sedentary adults, and, in a preliminary report, Bhella et al. (2) found reduced leg muscle oxidative metabolism by MRI during exercise in HFPEF patients. Furthermore, Drexler et al. (12) reported that the volume density of mitochondria and the surface density of mitochondrial cristae were significantly reduced in HFREF patients compared with HC subjects and that both were positively related to peak V̇o2. However, Mettauer et al. (48) reported that despite 60% lower peak V̇o2, the maximal vastus lateralis mitochondrial oxidative capacity was similar in HFREF patients compared with sedentary HC subjects. Thus, a prospective study with direct assessments is needed to determine whether HFPEF patients have abnormalities in mitochondrial function and oxidative metabolism and, if so, whether they contribute to their severely reduced peak V̇o2.

Limitations.

Although we found significant correlations, due to the cross-sectional design, we cannot determine whether the reduced percentage of type I fibers and capillary-to-fiber ratio in our HFPEF patients are causes or consequences of their severely reduced peak V̇o2.

Sex, a known potential confounder of both exercise capacity and skeletal muscle characteristics, was significantly different between groups. However, we adjusted all analyses for sex, a well-established and accepted method for controlling for the potential confounder's effect in the group comparison (38). Furthermore, all key results, including fiber type, capillary-to-fiber ratio, and their relationships to peak V̇o2, were confirmed in an additional case control analysis whereby control subjects and patients were carefully matched by sex. The body mass index was also different between groups. However, our results were unchanged after we adjusted for body mass index.

Our control group was, by design, healthy subjects without comorbidities. As such, we cannot exclude a contribution of the comorbidities that are common in HFPEF, such as hypertension and diabetes (63). However, the pattern of altered skeletal muscle fiber type and capillary-to-fiber ratio we observed in our elderly HFPEF patients is strikingly similar to that reported by others in HFREF patients (12, 39, 42, 43, 45, 49, 58, 64–67, 72), and the fiber type alteration is dissimilar to that seen with aging alone (40).

By study design, HFPEF patients were ambulatory, stable, well compensated, had no recent acute hospitalization, and were physically able to participate in exhaustive exercise testing. Our B-type natriuretic peptide levels were similar to other studies of stable HFPEF patients able to undergo maximal exercise testing (4, 5, 32, 50) and, as we have previously shown (35), were significantly twofold increased in HFPEF patients compared with HC subjects. Doppler LV diastolic function parameters were also abnormal in our HFPEF patients versus HC subjects. However, our results may not apply to HFPEF patients who are sicker, poorly compensated, or less clinically stable.

Finally, another limitation is that peak V̇o2 was determined as the highest O2 consumed at volitional exhaustion. Although not performed in the present study, a second square-wave test performed at a higher exercise attained than completed by our subjects during the incremental test would verify unambiguously whether a true maximal V̇o2 was reached.

Perspectives.

Regardless of the underlying mechanisms, these skeletal muscle abnormalities may be reversible with exercise training (1, 11, 16, 21, 27, 28, 49, 69, 71). In health and disease, exercise training can reverse the reduction in type I fibers, increase skeletal muscle mitochondrial volume density, and increase capillarity, and these changes are positively related to the training-related improvement in peak V̇o2 (1, 16, 21, 27, 69). In particular, increases in capillarity and therefore red blood cell volume caused by exercise training would be expected to elevate the diffusive O2 conductance and arteriovenous O2 difference. These favorable adaptations might also occur in older patients with HFPEF, since after endurance exercise training, the change in exercise arteriovenous O2 difference was strongly related to the increase in peak V̇o2 (24). There are a number of other intervention strategies that may potentially improve skeletal muscle function as well (6, 7, 49). These new potential therapeutic targets may be valuable since trials of exercise intolerance in HFPEF to date have been directed primarily at improving cardiovascular function and have largely been ineffective (17, 32, 46, 55).

Summary.

Older HFPEF patients have a significantly reduced percentage of slow twitch type I oxidative fibers, type I-to-type II fiber ratio, and capillary-to-fiber area ratio, and these alterations are associated with their severely reduced peak exercise V̇o2. Interventions designed to reverse these skeletal muscle abnormalities may improve the severe exercise intolerance in older HFPEF patients.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the following research grants: National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R37-AG-18915 and R01-AG-020583, The Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center of Wake Forest University NIH Grant P30-AG-021332, General Clinical Research Center of the Wake Forest School of Medicine NIH Grant MO1-RR-07122, and The Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center of Duke University NIH Grant P30-AG-028716 (to W. E. Kraus).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.W.K., B.J.N., and W.E.K. conception and design of research; D.W.K., B.J.N., W.E.K., M.F.L., J.E., and M.J.H. interpreted results of experiments; D.W.K. and M.J.H. drafted manuscript; D.W.K., B.J.N., W.E.K., M.F.L., J.E., T.M.M., and M.J.H. edited and revised manuscript; D.W.K., B.J.N., W.E.K., M.F.L., J.E., T.M.M., and M.J.H. approved final version of manuscript; W.E.K. and M.F.L. performed experiments; J.E. and T.M.M. analyzed data; J.E. prepared figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen P, Henriksson J. Capillary supply of the quadriceps femoris muscle of man: adaptive response to exercise. J Physiol 270: 677–690, 1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhella PS, Prasad A, Heinicke K, Hastings JL, Arbab-Zadeh A, Adams-Huet B, Pacini EL, Shibata S, Palmer MD, Newcomer BR, Levine BD. Abnormal haemodynamic response to exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 13: 1296–1304, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Russell SD, Kessler K, Pacak K, Becker LC, Kass DA. Impaired chronotropic and vasodilator reserves limit exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 114: 2138–2147, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CSP, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 3: 588–595, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CSP, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 56: 845–854, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caminiti G, Volterrani M, Iellamo F, Marazzi G, Massaro R, Miceli M, Mammi C, Piepoli M, Fini M, Rosano GM. Effect of long-acting testosterone treatment on functional exercise capacity, skeletal muscle performance, insulin resistance, and baroreflex sensitivity in elderly patients with chronic heart failure: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 919–927, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cittadini A, Saldamarco L, Marra AM, Arcopinto M, Carlomagno G, Imbriaco M, Del Forno D, Vigorito C, Merola B, Oliviero U, Fazio S, Saccá L. Growth hormone deficiency in patients with chronic heart failure and beneficial effects of its correction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 3329–3336, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coen PM, Jubrias SA, Distefano G, Amati F, Mackey DC, Glynn NW, Manini TM, Wohlgemuth SE, Leeuwenburgh C, Cummings SR, Newman AB, Ferrucci L, Toledo FGS, Shankland E, Conley KE, Goodpaster BH. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics are associated with maximal aerobic capacity and walking speed in older adults. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci 68: 447–455, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coggan AR, Spina RJ, King DS. Histochemical and enzymatic comparison of the gastrocnemius muscle of young and elderly men and women. J Gerontol 47: B71–B76, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies KJ, Donovan CM, Refino CJ, Brooks GA, Packer L, Dallman PR. Distinguishing effects of anemia and muscle iron deficiency on exercise bioenergetics in the rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 246: E535–E543, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downing J, Balady GJ. The role of exercise training in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 561–569, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drexler H, Riede J, Munzel T, Konig H, Funke E, Just H. Alterations of skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Circulation 85: 1751–1759, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duscha BD, Annex BH, Green HJ, Pippen AM, Kraus WE. Deconditioning fails to explain peripheral skeletal muscle alterations in men with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 1170–1174, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duscha BD, Annex BH, Keteyian SJ, Green HJ, Sullivan MJ, Samsa GP, Brawner CA, Schachat FH, Kraus WE. Differences in skeletal muscle between men and women with chronic heart failure. J Appl Physiol 90: 280–286, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duscha BD, Kraus WE, Keteyian SJ, Sullivan MJ, Green HJ, Schachat FH, Pippen AM, Brawner CA, Blank JM, Annex BH. Capillary density of skeletal muscle: a contributing mechanism for exercise intolerance in class II–III chronic heart failure independent of other peripheral alterations. J Am Coll Cardiol 33: 1956–1963, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duscha BD, Robbins JL, Jones WS, Kraus WE, Lye RJ, Sanders JM, Allen JD, Regensteiner JG, Hiatt WR, Annex BH. Angiogenesis in skeletal muscle precede improvements in peak oxygen uptake in peripheral artery disease patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2742–2748, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edelmann F, Aldo investigators -DHF. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the ALDO-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA 309: 781–791, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franssen F, Wouters E, Schols A. The contribution of starvation, deconditioning and ageing to the observed alterations in peripheral skeletal muscle in chronic organ diseases. Clin Nutr 21: 1–14, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez E, Messi ML, Zheng Z, Delbono O. Insulin-like growth factor-1 prevents age-related decrease in specific force and intracellular Ca2+ in single intact muscle fibres from transgenic mice. J Physiol 552: 833–844, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt GH, Sullivan M, Thompson PJ, Fallen EL, Pugsley SO, Taylor DW, Berman LD. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J 132: 919–923, 1985 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hambrecht R, Fiehn E, Yu J, Niebauer J, Weigl C, Hilbrich L, Adams V, Riede U, Schuler G. Effects of endurance training on mitochondrial ultrastructure and fiber type distribution in skeletal muscle of patients with stable chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 29: 1067–1073, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haykowsky M, Kouba EJ, Brubaker PH, Nicklas BJ, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Skeletal muscle composition and its relation to exercise intolerance in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol 113: 1211–1216, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Kritchevsky SB, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Impaired aerobic capacity and physical functional performance in older heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: role of lean body mass. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68: 968–975, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 120–128, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haykowsky MJ, Herrington DM, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Hundley WG, Kitzman DW. Relationship of flow mediated arterial; dilation and exercise capacity in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68: 161–167, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, John JM, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Kitzman DW. Determinants of exercise intolerance in elderly heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 265–274, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holloszy JO, Coyle EF. Adaptations of skeletal muscle to endurance exercise and their metabolic consequences. J Appl Physiol 56: 831–838, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingjer F. Effects of endurance training on muscle fibre ATP-ase activity, capillary supply and mitochondrial content in man. J Physiol 294: 419–432, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John JM, Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker P, Stewart K, Kitzman DW. Decreased let ventricular distensibility in response to postural change in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H883–H889, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz SD, Maskin C, Jondeau G, Cocke T, Berkowitz R, LeJemtel T. Near-maximal fractional oxygen extraction by active skeletal muscle in patients with chronic heart failure. J Appl Physiol 88: 2138–2142, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keteyian SJ, Duscha BD, Brawner CA, Green HJ, Marks CRC, Schachat FH, Annex BH, Kraus WE. Differential effects of exercise training in men and women with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J 145: 912–918, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitzman DW, Hundley WG, Brubaker P, Stewart K, Little WC. A randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial of enalapril in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction; effects on exercise tolerance, and arterial distensibility. Circ Heart Fail 3: 477–485, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Gottdiener JS, Arnold A, Boineau R, Aurigemma G, Marino EK, Lyles M, Cushman M, Enright PL; Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. Importance of heart failure with preserved systolic function in patients > or = 65 years of age. CHS Research Group. Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Cardiol 87: 413–419, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR, Sheikh KH, Sullivan M. Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular systolic function: failure of the Frank-Starling mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol 17: 1065–1072, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, Anderson RT, Hundley WG, Marburger CT, Brosnihan B, Morgan TM, Stewart KP. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA 288: 2144–2150, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Herrington DM, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Hundley WG, Abdelhamed A, Haykowsky MJ. Effect of endurance exercise training on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 62: 584–592, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Little WC. Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 3: 659–667, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Nizam A, Muller KE. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole, 2008, p. 198–202 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larsen A, Lindal S, Aukrust P, Toft I, Aarsland T, Dickstein K. Effect of exercise training on skeletal muscle fibre characteristics in men with chronic heart failure. Correlation between skeletal muscle alterations, cytokines and exercise capacity. Int J Cardiol 83: 25–32, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsson L, Sjodin B, Karlsson J. Histochemical and biochemical changes in human skeletal muscle with age in sedentary males, age 22–65 years. Acta Physiol Scand 103: 31–39, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maeder MT, Thompson BR, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Kaye DM. Hemodynamic basis of exercise limitation in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 56: 855–863, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magnusson G, Kaijser L, Rong H, Isberg B, Sylven C, Saltin B. Exercise capacity in heart failure patients: relative importance of heart and skeletal muscle. Clin Physiol 16: 183–195, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mancini DM, Walter G, Reichek N, Lenkinski R, McCully KK, Mullen JL, Wilson JR. Contribution of skeletal muscle atrophy to exercise intolerance and altered muscle metabolism in heart failure. Circulation 85: 1364–1373, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marburger CT, Brubaker PH, Pollock WE, Morgan TM, Kitzman DW. Reproducibility of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in elderly heart failure patients. Am J Cardiol 82: 905–909, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massie BM, Simonini A, Sahgal P, Wells L, Dudley GA. Relation of systemic and local muscle exercise capacity to skeletal muscle characteristics in men with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 27: 140–145, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, Anderson S, Donovan M, Iverson E, Staiger C, Ptaszynska A; I-PRESERVE Investigators. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 359: 2456–2467, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maurer MS, Schulze PC. Exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: shifting focus from the heart to peripheral skeletal muscle. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 129–131, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mettauer B, Zoll J, Sanchez H, Lampert E, Ribera F, Veksler V, Bigard X, Mateo P, Epailly E, Lonsdorfer J, Ventura-Clapier R. Oxidative capacity of skeletal muscle in heart failure patients versus sedentary or active control subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 947–954, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Middlekauff HR. Making the case for skeletal myopathy as the major limitation of exercise capacity in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 3: 537–546, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mottram PM, Haluska B, Leano R, Cowley D, Stowasser M, Marwick TH. Effect of aldosterone antagonism on myocardial dysfunction in hypertensive patients with diastolic heart failure. Circulation 110: 558–565, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicklas B, Leng I, Delbono O, Kitzman DW, Marsh A, Hundley WG, Lyles M, O'Rourke KS, Annex BH, Kraus WE. Relationship of physical function to vastus lateralis capillary density and metabolic enzyme activity in elderly men and women. Aging Clin Exper Res 20: 302–309, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 355: 251–259, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poole DC, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Musch TI. Muscle oxygen transport and utilization in heart failure: implications for exercise (in)tolerance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1050–H1063, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puntawangkoon C, Kitzman D, Kritchevsky S, Hamilton C, Nicklas B, Leng X, Brubaker P, Hundley WG. Reduced peripheral arterial blood flow with preserved cardiac output during submaximal bicycle exercise in elderly heart failure. J Cardiovasc Mag Reson 11: 48, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Redfield M, Chen H, Borlaug B, Semigran M, Lee K, Lewis G, LeWinter M, Rouleau J, Bull D, Mann D, Deswal A, Stevenson L, Givertz M, Ofili E, O'Conner C, Felker G, Goldsmith S, Bart B, McNulty S, Ibarra J, Lin G, Oh J, Patel M, Kim R, Tracy R, Velazquez E, Anstrom K, Hernandez A, Mascette A, Braunwald E; RELAX Trial. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 309: 1268–1277, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney R. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 333: 1190–1195, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rossiter HB. Exercise: kinetic considerations for gas exchange. Compr Physiol 1: 203–244, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schaufelberger M, Andersson G, Eriksson BO, Grimby G, Held P, Swedberg K. Skeletal muscle changes in patients with chronic heart failure before and after treatment with enalapril. Eur Heart J 17: 1678–1685, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schocken DD, Arrieta MI, Leaverton PE, Ross EA. Prevalence and mortality rate of congestive heart failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol 20: 301–306, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scott JM, Haykowsky MJ, Eggebeen J, Morgan TM, Brubaker PH, Kitzman DW. Reliability of peak exercise testing in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol 110: 1809–1813, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simonini A, Long CS, Dudley GA, Yue P, McElhinny J, Massie BM. Heart failure in rats causes changes in skeletal muscle morphology and gene expression that are not explained by reduced activity. Circ Res 79: 128–136, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stehle JR, Jr, Leng X, Kitzman DW, Nicklas BJ, Kritchevsky SB, High KP. LPS binding protein (LBP), a surrogate marker of microbial translocation is associated with physical function in healthy older adults. J Gerontol Med Sci 67: 1212–1218, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stuart CA, McCurry MP, Marino A, South MA, Howell MEA, Layne AS, Ramsey MW, Stone MH. Slow-twitch fiber proportion in skeletal muscle correlates with insulin responsiveness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98: 2027–2036, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sullivan MJ, Green HJ, Cobb FR. Skeletal muscle biochemistry and histology in ambulatory patients with long-term heart failure. Circulation 81: 518–527, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sullivan MJ, Green HJ, Cobb FR. Altered skeletal muscle metabolic response to exercise in chronic heart failure. Relation to skeletal muscle aerobic enzyme activity. Circulation 84: 1597–1607, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sullivan MJ, Duscha BD, Klitgaard H, Kraus WE, Cobb F, Saltin B. Altered expression of myosin heavy chain in human skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29: 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toth M, Matthews DE, Ades PA, Tischler MD, Van Buren P, Previs M, LeWinter MM. Skeletal muscle myofibrillar protein metabolism in heart failure: relationship to immune activation and functional capacity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E685–E692, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Evans JC, Reiss CK, Levy D. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 33: 1948–1955, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ventura-Clapier R, Mettauer B, Bigard X. Beneficial effects of endurance training on cardiac and skeletal muscle energy metabolism in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 73: 10–18, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vescovo G, Serafini F, Facchin L, Tenderini P, Carraro U, Dalla Libera L, Catani C, Ambrosio GB. Specific changes in skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain composition in cardiac failure: differences compared with disuse atrophy as assessed on microbiopsies by high resolution electrophoresis. Heart 76: 337–343, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vogiatzis I, Zakynthinos SG. The physiological basis of rehabilitation in chronic heart and lung disease. J Appl Physiol 115: 16–21, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams A, Selig S, Hare D, Hayes A, Krum H, Patterson J, Geerling R, Toia D, Carey MF. Reduced exercise tolerance in CHF may be related to factors other than impaired skeletal muscle oxidative capacity. J Card Fail 10: 141–148, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]