Abstract

C4 grasses are favoured as forage crops in warm, humid climates. The use of C4 grasses in pastures is expected to increase because the tropical belt is widening due to global climate change. While the forage quality of Paspalum dilatatum (dallisgrass) is higher than that of other C4 forage grass species, digestibility of warm-season grasses is, in general, poor compared with most temperate grasses. The presence of thick-walled parenchyma bundle-sheath cells around the vascular bundles found in the C4 forage grasses are associated with the deposition of lignin polymers in cell walls. High lignin content correlates negatively with digestibility, which is further reduced by a high ratio of syringyl (S) to guaiacyl (G) lignin subunits. Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) catalyses the conversion of cinnamoyl CoA to cinnemaldehyde in the monolignol biosynthetic pathway and is considered to be the first step in the lignin-specific branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway. We have isolated three putative CCR1 cDNAs from P. dilatatum and demonstrated that their spatio-temporal expression pattern correlates with the developmental profile of lignin deposition. Further, transgenic P. dilatatum plants were produced in which a sense-suppression gene cassette, delivered free of vector backbone and integrated separately to the selectable marker, reduced CCR1 transcript levels. This resulted in the reduction of lignin, largely attributable to a decrease in G lignin.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11248-014-9784-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: C4 forage grass, Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, Lignin, Paspalum dilatatum

Introduction

Dallisgrass (Paspalum dilatatum Poir.) is a C4 grass native to South America, but widely grown for forage in tropical, subtropical and warm temperate regions of the world. Several polyploid biotypes, including sexual tetraploids, apomictic pentaploids and hexaploids have been described (Casa et al. 2002). Valued for its vigour, dallisgrass produces yields of up to 15 tons of dry matter per hectare (Cook et al. 2005) with crude protein concentrations of up to 18.6 % (Baréa et al. 2007). It can withstand heavy grazing and is somewhat tolerant to frost and water stress (Hutton and Nelson 1968; Robinson et al. 1988).

With the widening of the tropical belt due to global climate change (for review see Seidel et al. (2008) the market for C4 forages grasses is set to increase. However, while the forage quality of P. dilatatum is higher than that of other C4 forage grass species, digestibility of warm-season grasses is, in general, poor compared with most temperate grasses (Wilson 1994). This is due to the presence of lignin deposits in the thick-walled parenchyma bundle-sheaths around each vascular bundle (Wilson 1993). Lignin acts as a physical barrier to the microbial enzymes that digest polysaccharides, limiting the achievable degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose and limiting the digestible energy available to ruminants (Jung and Allen 1995). Consequently, modification of the lignin biosynthetic pathway, either by analyses of mutants or by genetic modification, is of great interest (Gordon and Neudoerffer 1973; Barrière et al. 1994; Halpin et al. 1994; Bernard-Vailh et al. 1996; Guo et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2004; Li et al. 2008; Hisano et al. 2009; Tu et al. 2010).

Lignin, found in the cell walls of vascular plants, is a complex heteropolymer resulting from radical coupling reactions of three main monolignols: p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol and sinapyl alcohol. The degree of methoxylation of the phenyl ring differs in each subunit giving rise to hydroxyphenyl (H), guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) lignin, respectively (Rogers and Campbell 2004).

The first step in the lignin-specific branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway is catalysed by cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR). This enzyme regulates the carbon flux towards lignin and is thus a viable target to alter lignin levels (Lacombe et al. 1997; Baucher et al. 1998). Genes encoding CCR have been studied in many species including the model plants Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa and Populus tremuloides (Costa et al. 2003; Li et al. 2003; Kawasaki et al. 2006). CCR1 genes have been found to be preferentially expressed in the stems of Panicum virgatum, A. thaliana, Medicago truncatula, Triticum aestivum, Lolium perenne and Zea mays (Pichon et al. 1998; Lauvergeat et al. 2001; Goujon et al. 2003; Larsen 2004; Ma and Tian 2005; Escamilla-Treviño et al. 2010; Tu et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2010) and are thus thought to be involved in lignification. A reduction in the total lignin level and changes in monolignol composition were positively correlated with improved digestibility in the brown-midrib (bm) mutants of Z. mays as well as in transgenic plants in which caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase (COMT) was down-regulated (Baucher et al. 1998; Casler and Vogel 1999; Piquemal et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2004; Hisano et al. 2009; Tu et al. 2010; Tamasloukht et al. 2011). Down-regulation of CCR1 expression has been achieved in Nicotiana tabacum (Dauwe et al. 2007), Medicago sativa (Jackson et al. 2008), Solanum lycopersicon (Van der Rest et al. 2006) Z. mays (Park et al. 2012) and hybrid poplar (Populus tremula × Populus alba) (Leplé et al. 2007) as well as in the C3 forage, L. perenne, in which a decrease in total lignin was observed to correlate with improved digestibility (Tu et al. 2010).

Even moderate increases in digestibility have significant economic consequences; in L. perenne a 5–6 % increase in digestibility was estimated to increase summer milk production in southern Australia by up to 27 % (Smith et al. 1998). In this study we have isolated and characterised putative CCR1 cDNAs from P. dilatatum cv. Primo, a tetraploid sexually reproductive commercial cultivar. We describe the pattern of lignin deposition and CCR1 transcript levels during plant development and analyse the impact of down-regulating CCR1 on lignin composition and digestibility. Gene silencing was triggered by expression of a frame-shift mutant of a CCR gene, which was delivered separately to the selectable marker cassette. Both cassettes were delivered free of vector backbone.

Experimental procedures

Plant material

Seeds of P. dilatatum cv. Primo, a tetraploid (2n = 4x = 40) sexually reproductive cultivar, kindly provided by Gustavo Schrauf, Facultad de Agronomía de la Universidad de Buenos Aires (FAUBA), were grown in glasshouses (21 °C, 14 h photoperiod/14 °C, 10 h dark period) or growth cabinets (21 °C, 14 h photoperiod/16 °C, 10 h dark period).

Isolation of putative cinnamoyl-CoA cDNAs from P. dilatatum

Reference sequences of CCR1 genes from Sorghum bicolor, Z. mays, P. virgatum and L. perenne were aligned and the consensus sequence was used to design primers to conserved regions. Sequences of all primers are provided as supporting information (Online Resource 1). Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of ground tissue (stems, roots, leaf blades and inflorescences) from the final reproductive stage of P. dilatatum cv. Primo plants using the RNeasy® Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. A cDNA library was prepared from pooled RNA using the SMART™ cDNA Synthesis kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA). First strand cDNA was reverse transcribed using SMARTScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase and SMART IV™ oligonucleotides (Clontech Laboratories) and putative CCR genes were amplified from this template. Further transcripts were identified using the SMARTer™ RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech Laboratories). After re-amplification with proofreading polymerases, full-length coding sequences were cloned and sequenced using ABI Sanger Sequencing and Big Dye Terminator v3.1 (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, USA).

Southern hybridisation analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from leaf tissue using a standard cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol (Doyle and Doyle 1987) and 10 μg was digested with one or more of the restriction enzymes HindIII, EcoRI and SacI in separate reactions and separated on a 0.8 % (w/v) agarose gel. Following electrophoresis, DNA was transferred to a Hybond N membrane (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) using established protocols (Sambrook et al. 1989). A PdCCR-specific probe was generated using a PCR-based digoxigenin (DIG) Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Probes specific to the promoter of the polyubiquitin gene from Z. mays, present in the CCR-frameshift transgene cassette, and to the nptII selection gene were also made. Sequences of all primers are provided in Online Resource 1. Hybridisation with the PdCCR-specific probe was performed at 58 °C overnight and with the Z. mays polyubiquitin gene promoter and nptII gene probes at 55 °C overnight. A chemiluminescent detection protocol was used as per manufacturer’s instructions (DIG Luminescent Detection Kit, Roche).

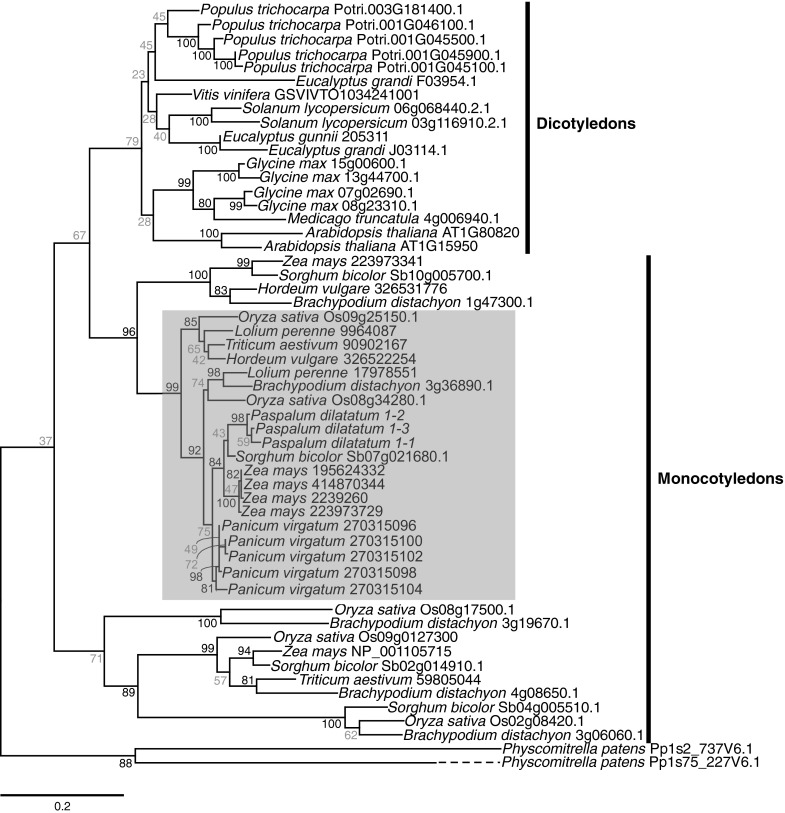

Phylogenetic analysis

The deduced amino acid sequences of the PdCCR transcripts identified in this study were aligned with previously derived CCR gene sequences as well as with sequences identified from publically available complete plant genomes using BLASTx and tBLASTn (cut-off of e−4). Reciprocal BLAST was performed against the A. thaliana and O. sativa genomes. Alignments were made using ClustalX (Larkin et al. 2007) and imported into Mesquite (Maddison and Maddison 2011) for refinement. A preliminary phylogenetic analysis showed that the clade containing the conserved NWYCY motif was monophyletic. Sequences from this clade were then subjected to rigorous analyses using the two most-closely related genes encoded in the genome of the bryophyte, Physcomitrella patens (from which no genes containing the conserved motif were identified) as an out-group. Ambiguously aligned characters were excluded in Mesquite, resulting in a matrix of 54 taxa and 313 characters. A maximum likelihood phylogeny was inferred using PhyML v3.0 (Guindon and Gascuel 2003) with the LG substitution model and eight categories of substitution rates. The alpha value and number of invariable sites were calculated from the data sets. Branch support was assessed using ML bootstrap analysis (PhyML with eight categories and 100 replications).

Expression analysis

RNA was purified from plant tissue using the ZR Plant RNA MiniPrep™ Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) or the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Expression of PdCCR during development of non-transgenic plants was analysed by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) designed to amplify all CCR transcripts identified. Data was normalised using expression values of elongation factor-1 alpha (EF1α) as a reference gene (Silveira et al. 2009). Quantification was performed using SYBR Green Mastermix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with 200 nM of each primer for PdCCR amplification and with 300 nM of each primer for EF1α expression analysis. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, and 60 °C (EF1α) or 63 °C (PdCCR) for 1 min, and 1 cycle of 95 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 30 s and 95 °C for 30 s. Expression of PdCCR in transgenic plants was determined in the same way except that a set of primers spanning the coding and 3’ untranslated region was designed to amplify all CCR transcripts but to exclude amplification of transcript from the transgene cassette. Cycling conditions for this assay were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, and 60 °C (EF1α) or 68 °C (PdCCR) for 1 min, and a hold of 95 °C for 1 min followed by a dissociation curve (60 °C to 95 °C). Sequences of all primers are provided in Online Resource 1. A tenfold dilution series of standard templates (linear double-stranded DNA) was prepared for absolute quantification. Standard error was calculated from three biological replicates. Amplification was performed on either an Mx3005P (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or a C1000 thermal cycler with the CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Results were analysed using the MxPro (Stratagene) or CFX Manager (Bio-Rad) software packages. Relative quantification was calculated according to the 2−∆∆Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Construction of expression cassettes

Expression cassettes consisting of the promoter and 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the polyubiquitin (Ubi) gene from Z. mays (Toki et al. 1992), followed by the entire coding sequence of PdCCR1-1 with a frame-shift created by deleting the seventh base-pair downstream of the start codon and the 3′ UTR comprising transcriptional terminator and polyadenylation site from the fructosyltransferase 4 (FT4) gene from L. perenne were synthesised (GeneArt, Life Technologies, Regensberg, Germany). A plant selectable marker cassette consisting of the promoter and 5′ UTR from the actin (act1) gene from O. sativa (McElroy et al. 1990) followed by the neomycin phosphotransferase (npt2) gene was also synthesised. This cassette was terminated with the 3′ UTR, comprising transcriptional terminator and polyadenylation site, from the octopine synthase (oct) gene from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Cassettes were liberated from the vector backbones by restriction digestion and separated from the plasmid DNA fragment using the Elutrap system (Whatman, Maidstone, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of transgenic P. dilatatum plants

A single genotype, Primo-11, was selected on the basis of observing shoot regeneration from embryogenic callus (EC) derived from mature seeds of P. dilatatum cv. Primo. This approach, including methods for surface sterilisation, callus induction from mature seed and vegetative in vitro tillers, shoot regeneration and maintenance of vegetative in vitro tillers, was adapted from Bajaj et al. (2006). Modifications to this method include a 15 min immersion of seeds in 50 % (v/v) sulphuric acid, the omission of endophyte control treatments, Murashige and Skoog (MS) media (Murashige and Skoog 1962) solidified with 0.7 % (w/v) agar (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), the use of MS supplemented with 3 % (w/v) sucrose and 1 μM Kinetin (MSK) for shoot regeneration, the use of MS supplemented with 3 % (w/v) sucrose and 15 μM 6-benzylaminopurine (BA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for maintenance medium and the use of MS supplemented with 3 % (w/v) sucrose and 22.6 μM 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for callus induction medium.

Five to seven days prior to transformation EC were preconditioned by osmotic treatment on MS medium supplemented with 3 % sucrose, 64 g/L mannitol and 6 μM 2,4-D and incubated in the dark for 4 h at 24 ± 2 °C. EC were then bombarded with 0.6 μm gold particles coated with equal quantities of cassette DNA using the PDS 1000/He system (Bio-Rad) with a system pressure of 1,100 psi and a vacuum degree of 9.5 kPa (28 inches of mercury). Bombarded EC were kept in the dark for 16 h at 24 ± 2 °C before transfer to callus induction medium supplemented with 50 mg/L paromomycin as the selective agent. After 1 week, EC were transferred to regeneration medium supplemented with 50 mg/L paromomycin and incubated for 2 weeks at 24 ± 2 °C under a 16 h photoperiod at a photon flux density of 75 μM m−2 s−1. EC were subcultured every 2 weeks for 6 weeks on regeneration medium supplemented with 50 mg/L paromomycin. Putative transgenic plants with established roots were transferred to potting mix and grown in the glasshouse in conditions described above. Transgene was confirmed using qPCR to detect the endogenous gene EF1α, the selectable marker cassette and the PdCCR frameshift cassette. Sequences of all primers are provided as supporting information (Online Resource 1). Transgenic status was verified and copy number was determined by Southern hybridisation analysis as described above. Each transgenic line and two non-transgenic lines of the same genetic background, also regenerated in tissue-culture, were cloned into three biological replicates. Tissue samples of leaf blades and pseudostems of equivalent maturity were taken from each clone. Each sample was frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground and divided to provide material for expression and biochemical analyses. Each sample was analysed in triplicate to provide technical replicates.

Histochemical staining of lignin

The Mäule reagent specifically stains syringyl (S) lignin subunits red and guaiacyl (G) subunits brown (Iiyama and Wallis 1990; Lin and Dence 1992). Transverse sections of stems at different development stages were stained as previously described (Chen et al. 2002). Images were captured using a Leica MZ FLIII stereo fluorescence microscope with a Leica DFC300F colour camera (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Lignin content and composition analysis

Tissue samples were freeze-dried and homogenised to a fine powder using a mixer mill (MM400, Retsch Technology, Haan, Germany) at 25 Hz for two minutes. For isolation of cell walls, 100 mg of powdered leaf blade or stem tissue was sequentially extracted with hot water, ethanol and acetone. The remaining cell wall extract was used for determination of total lignin content and subunit composition analysis. The lignin content of leaf and stem tissues was quantified using the acetyl bromide soluble lignin method (Iiyama and Wallis 1990) with 6 mg of cell wall extract used per assay. Monolignol composition was determined with the thioacidolysis method (Rolando et al. 1992) using 8 mg of each cell wall extract per assay. Statistical analysis (Student t Test, P < 0.05) was carried out using Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA).

Metabolite analysis of transgenic Paspalum dilatatum plants relative to control plants

Tissue samples were freeze-dried and homogenised to a fine powder. For the analysis of intermediate metabolites involved in monolignol synthesis, 50 mg of powdered leaf-blade tissue was extracted twice with one mL of 80 % methanol. The supernatants were combined and used directly for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation was achieved using a 150 × 2.1 mm Agilent Eclipse XDB 1.9 μm C18 column fitted to an Agilent 1290 Infinity HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Metabolites were eluted from the column using a gradient mobile phase (containing water and acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The compounds were detected with a LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a heated electrospray ionisation source and a positive–negative switching scanning mode (both over the 80–2,000 m/z range). Standard compounds, namely p-coumaric acid, phenylalanine, ferulic acid, sinapic acid, and caffeic acid (all from Sigma-Aldrich) were analysed under the same conditions to identify metabolites of interest within the samples. Quantification of metabolites was performed using LCquan 2.0 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and statistical analysis (Student t Test, P < 0.05) was carried out using Excel 2003 (Microsoft).

Near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS)

Vegetative herbage samples (cut 50 mm above the soil surface) were dried for 72 h at 55 °C and ground to a fine powder using a MM400 mixer mill (Retsch Technology) at 30 Hz for 2 min. Spectral data analysis was obtained and analysed and nutritive value estimated as described by Tu et al. (2010).

Results

Isolation and characterisation of PdCCR1

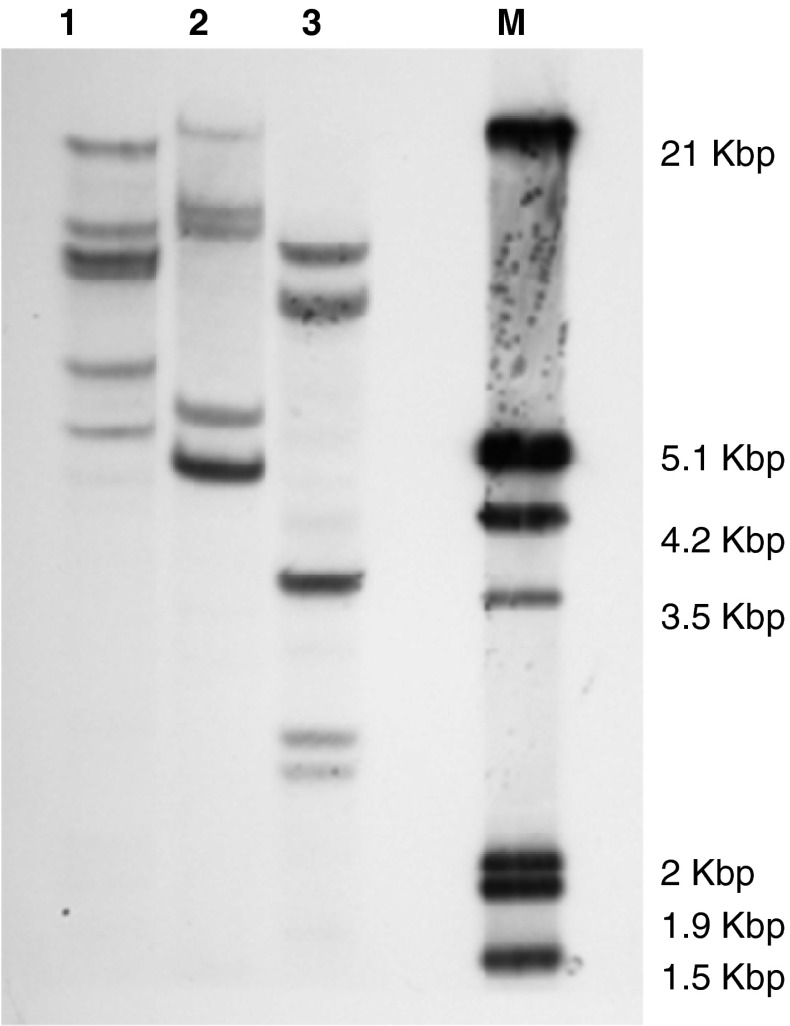

Transcripts encoding open reading frames, from which the inferred translations suggested functional CCR proteins, were isolated by use of primers designed to conserved regions (NPDDPK and DYDAI; RV/MVFTS and EQMVEP; VVNPVL and TVNASI) of the coding sequences of CCR genes from monocotyledonous species and rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE). Three cDNAs with high identity (97–99 %) in the coding region but divergent in the 3′ UTRs were identified. Southern hybridisation analysis with a probe from the coding region revealed four clear bands and one doublet band in DNA digested with HindIII and five bands, one having twice the intensity of the others, can be seen in DNA digested with EcoRI and SacI (Fig. 1). The simplest interpretation is that there are three loci on each of the two sub-genomes although it possible that the bands are different alleles of fewer loci.

Fig. 1.

Southern hybridisation analysis of genomic DNA (10 μg per lane) purified from P. dilatatum plants digested with HindIII (1), EcoRI (2), SacI (3) and probed with a 337 bp DIG-labelled fragment of a CCR gene amplified from P. dilatatum. M DIG Marker III

The inferred amino acid sequences of the coding regions from the three full-length cDNAs isolated were compared to previously characterised CCR proteins. The motif NWYCY, previously suggested as the catalytic site for the enzymatic activity, was present in all cloned cDNAs. A βαβ secondary structure at the N-terminus, which corresponds to the conserved binding fold domain NAD/NADP(H)-dependent dehydrogenases and reductases, was located between residues 22 and 51 of the predicted proteins encoded in the cDNAs amplified from P. dilatatum. Phylogenetic analysis of CCR proteins encoded in plant genomes revealed three major clades: one comprised of dicotyledons and two comprised of monocotyledons, each with moderate support (Fig. 2). A separation that would support the functional divergence of CCR in higher plants into those with roles in defense-related lignin deposition and others involved in developmentally related lignification was not observed. In dicotyledons, the proteins associated with each function, for example CCR1 and CCR2 from A. thaliana, were shown to be the result of duplications that occurred post-speciation (Fig. 2). The sequences from P. dilatatum grouped with strong (99 bootstraps) support with proteins from monocotyledons described as CCR1, including those from L. perenne, T aestivum and Z. mays (accession numbers 17978551, 90902167 and 2239260, respectively), for which function has been linked to lignin deposition. Within this clade, the P. dilatatum proteins are closely related to proteins encoded in the genomes of other C4 species (P. virgatum, Sorghum bicolor and Z. mays) (Fig. 2). We have therefore named the three coding sequences cloned from P. dilatatum as PdCCR1-1, PdCCR1-2 and PdCCR1-3 (KC886283-5).

Fig. 2.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny of deduced CCR protein sequences from Viridaeplantae. Numbers at nodes correspond to ML bootstrap support. Moderate to strong support (>80) is shown in black, and weak support (>79) is shown in grey. The shaded box highlights CCR1 proteins from monocotyledons. The dashed line indicates a long branch

The spatio-temporal pattern of PdCCR1 expression during plant development correlates with lignification

Three developmental stages of P. dilatatum cv. Primo, vegetative (V), early reproductive (R1) and late reproductive (R2), were selected for analysis of PdCCR1 expression, lignin deposition and composition. At V stage true stems have not yet formed and the plant is described as juvenile. Pseudostems are composed of the folded or rolled bases of leaves that have yet to emerge within a sheath. The reproductive stage is divided into early reproductive, R1, defined by the emergence of an inflorescence and late reproductive, R2, when the inflorescence is fully emerged and anthesis has commenced. At R1 and R2 stages almost all stems contain three internodes, basal (I1), middle (I2) and upper (I3), into which tissue was divided for analysis.

The spatio-temporal expression pattern of PdCCR1 expression through plant development was determined by qRT-PCR analysis of leaf blades and pseudostems sampled from the V stage and in the stem internodes and corresponding leaf from each internode at the R1 and R2 developmental stages using primers that detected all of the transcripts identified. The content of lignin as percentage of cell wall residue from the same tissues was quantified using an acetyl bromide soluble lignin assay.

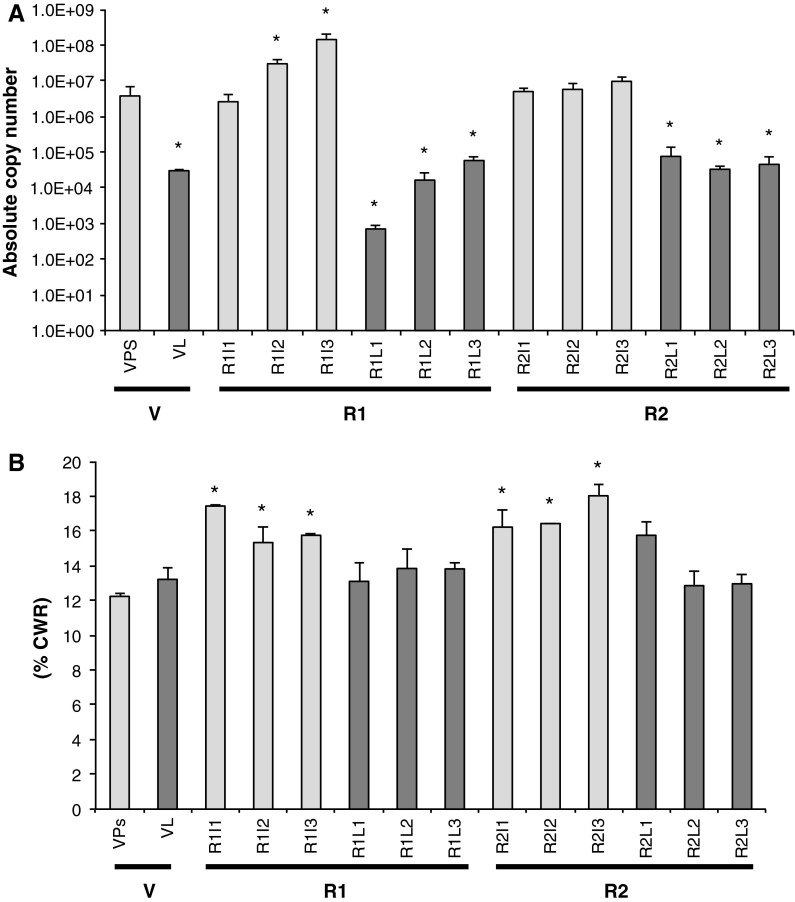

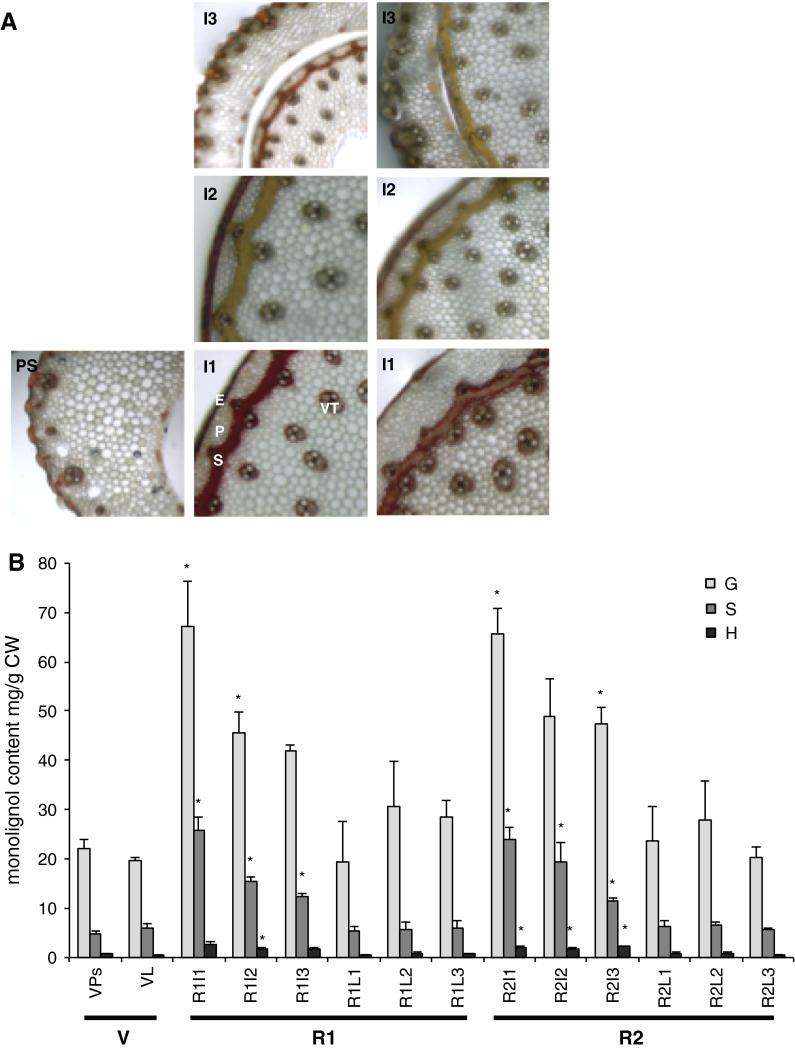

PdCCR1 transcripts were detected in leaf blades and pseudostem tissues sampled from plants at the V stage and also in all internodes of the stem and in all leaf blades from plants at both reproductive stages. The highest levels of expression were observed in tissues sampled from the uppermost internodes of stems at the early reproductive stage (R1I3) (Fig. 3A). There was a correlation between lignin deposition and the development of true stems. Significantly more lignin was found in all R1 and R2 stage internodes than in V stage pseudostems (Fig. 3B). Lower levels of PdCCR1 transcripts were observed in tissues in which lignification was minimal but also in highly lignified tissues such as stems at R2 stage, the latter of which were the most lignified tissues analysed (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference in the lignin content of pseudostems and leaf blades sampled at the vegetative stage although PdCCR1 expression in leaf blades was significantly lower than in pseudostems (Fig. 3). This indicates that lignin deposition occurs early in V stage leaf development and that expression of PdCCR1 declines after the emergence of the blade. To determine lignin composition, transverse sections of stems were taken from all three internodes at the R1 and R2 stages and also from pseudostems sampled at the V stage. Sections were stained histochemically using Mäule reagent, which stains G and S lignin brown and red, respectively. Lignin accumulation was observed in vascular, epidermal and sclerenchyma cells. The transition from vegetative to reproductive development was associated with an increase in the number of Mäule-stained cells and a colour shift from brownish-yellow to red indicating an increase in S lignin as the plant matures (Fig. 4A). Within the R1 and R2 stages an increasing amount of red coloration was observed in sections from the basal parts of the stems compared to the less-developed upper internodes (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 3.

a PdCCR1 expression and b lignin content of cell wall extracts as percentage of cell wall residue (% CWR) quantified using an acetyl bromide soluble lignin assay in P. dilatatum tissues through development. Values are average and standard errors of three biological replicates. V Vegetative stage (Ps Pseudostem, L leaf), R1 early reproductive stage, R2 late reproductive stage (I1 internode 1, I2 internode 2, I3 internode 3, L1 leaf 1, L2 leaf 2, L3 leaf 3). Asterisks indicate a significant difference (t test) relative to V stage pseudostems (P < 0.05)

Fig. 4.

Composition of lignin in P. dilatatum stems and leaf blades through development as determined by a Mäule staining of transverse sections and b thioacidolysis of cell wall extracts. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (t test) relative to V stage pseudostems (P < 0.05). V Vegetative stage (Ps Pseudostem, L leaf), R1 early reproductive stage, R2 late reproductive stage (I1 internode 1, I2 internode 2, I3 internode 3, L1 leaf 1, L2 leaf 2, L3 leaf 3). Epidermal cells (E), Parenchyma cells (P), Sclerenchyma cells (S), Vascular tissue (VT), scale bar = 100 μm. mg/g CW = mg per gram of dry cell wall residues (mean and standard error of three biological replicates) G guaiacyl lignin, H hydroxyphenyl lignin, S syringyl lignin

Thioacidolysis of cell wall extracts to determine lignin subunit composition also showed that the content of G- and S-lignin increased as plants transitioned to the reproductive stage (Fig. 4B). In particular, the basal internodes of stems at the early reproductive stage (R1I1) contained five times as much S-lignin and twice as much G-lignin as pseudostems at V stage. This resulted in a change in S/G ratio from 0.19 to 0.35. Within reproductive stems the content of G- and S-lignin decreased with height. The S/G ratio was greatest in basal internodes (0.35 at R1 stage and 0.33 at R2 stage) and lowest in uppermost internodes (0.27 at R1 stage and 0.23 at R2 stage) (Fig. 4B). Conversely, no significant difference was observed in the lignin composition of leaf blades with the S/G ratio remaining between 0.20 and 0.26 in samples taken at all stages of development (Fig. 4B). The content of H-lignin remained low, typically 2–3 % of total lignin, in all tissues sampled (Fig. 4B).

Downregulation of PdCCR in transgenic P. dilatatum plants

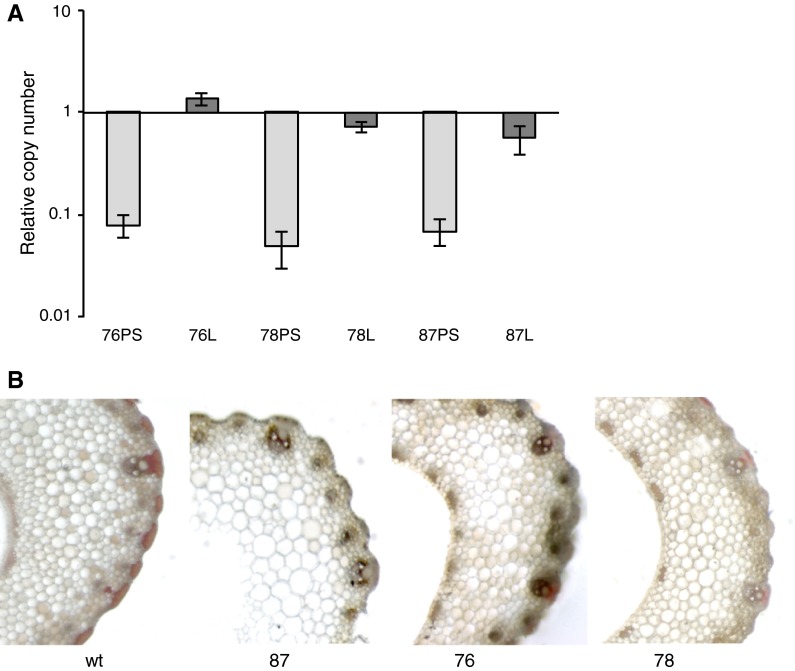

Putative transgenic P. dilatatum plants, resistant to paromomycin were initially tested for the presence of transgenes by Southern hybridisation analysis (see Online Resource 2). Probes specific to the promoter of the polyubiquitin gene from Z. mays, designed to detect the PdCCR cassette, and to the nptII gene indicated that >5, 2 and 5 copies of the PdCCR cassette and >5, 1 and 6 copies of the nptII cassette were integrated in lines 76, 78 and 87 respectively (see Online Resource 2). In each line, the pattern of bands obtained with the two probes differed, indicating separate integrations of the PdCCR and nptII cassettes (see Online Resource 2), which suggests that the selectable marker may be removed by segregation in subsequent generations.

In all three transgenic lines, the abundance of PdCCR transcripts in pseudostem tissue was found to be at least ten-fold lower than that of wild-type control plants (Fig. 5) indicating that the frame-shift cassettes had successfully induced gene-silencing. In leaf blades the reduction was more moderate with two lines showing only a two to three fold reduction in PdCCR transcript level (Fig. 5). However, expression of PdCCR1 transcripts in V stage leaf blades declines during development and lignin deposition is likely to have taken place when the young leaf was still rolled and part of the pseudostem (Fig. 4). Therefore, although leaf blades and pseudostems show comparable lignin content (Fig. 3B) and composition (Fig. 4), pseudostem tissue is the most appropriate V-stage tissue in which to compare PdCCR1 expression levels.

Fig. 5.

a Expression of CCR1 in pseudostems and leaf blades of transgenic lines of P. dilatatum normalised to the wild-type. Data shown is mean and standard error of three replicates of each line. PS pseudostem, L leaf blade b Mäule staining of transverse sections of pseudostems from wild-type and transgenic lines of P. dilatatum. All samples were taken from plants at the vegetative stage

Although lignin content is lower in the vegetative stage than in reproductive stages,

subsequent analysis of lignin content and composition focussed on leaf blades from plants at the V stage, since this is the typical stage where grazing occurs and where gains in digestibility will be of greatest consequence. Lignin content in leaf blades was reduced by 20 % in line 76 (Table 1). Thioacidolysis analysis detected a decrease in the level of guaiacyl (G) subunits leading to a significant change in the S/G ratio all three lines (Table 1). This reduction in lignin in pseudostems sampled at the V stage was also observed histochemically using Mäule reagent. Transgenic lines were less intensely stained when compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 5B). Additionally, metabolic profiling showed that the hydroxycinnamates p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid and caffeic acid were present at significantly higher levels in transgenic lines compared to the wild-type plants, indicating that intermediates of lignin-biosynthesis were re-directed into other pathways (see Online Resource 3).

Table 1.

Lignin content (% dry cell wall residues), composition (mg/g dry cell wall residues), and S/G ratio in leaf blades of transgenic lines and wild-type controls

| AcBr-soluble Lignin | G Lignin | S Lignin | H Lignin | S/G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type control | 15.07 ± 0.38 | 6.47 ± 0.79 | 1.69 ± 0.23 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.26 |

| 78 | 13.94 ± 0.31 | 5.28 ± 0.63 | 1.70 ± 0.24 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.32* |

| 87 | 15.39 ± 0.55 | 5.07* ± 0.17 | 1.57 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0.31* |

| 76 | 12.28* ± 0.59 | 4.11 ± 0.45 | 1.63 ± 0.13 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.40* |

Error bars indicate standard errors (n = 3). Asterisks indicate a significant difference (t test) relative to the wild-type control (P < 0.05)

Estimation of in vivo dry matter digestibility (IVVDMD) was performed using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS) as per Tu et al. (2010). Two transgenic lines showed a significant increase in IVVDMD in leaf blades (up to 4 %) in comparison to wild-type control lines, which correlated with a reduction in lignin (Online Resource 4).

Discussion

The influence of lignin composition on cell wall digestibility has been studied in a number of forage species (Jung and Vogel 1986; Buxton and Russell 1988; Akin 1989; Jung and Deetz 1993; Grabber 2005). Increases in global mean temperature and expansion of the tropical zone mean that C4 grasses will become suitable forage crops in some regions that have historically been temperate. P. dilatatum, which is already grown for forage in sub-tropical regions, is a candidate species. In general, the lignin content (% dry cell wall) of C4 grasses is higher than that of C3 grasses (Jung and Vogel 1986). The lignin content of pseudostems from P. dilatatum plants at the early reproductive stage was found to be 5 % higher than that reported for equivalent tissues in the C3 grass L. perenne (Tu et al. 2010). Similarly, the basal internodes of stems at the late reproductive stage were found to have 5 % more lignin than equivalent tissue from F. arundinacea (Chen et al. 2002). Lignin composition in monocotyledons changes as plants transition from vegetative to reproductive developmental stages with S-lignin increasing and G-lignin decreasing upon flowering (Anterola and Lewis 2002; Chen et al. 2002; Guillaumie et al. 2008; Tu et al. 2010). In P. dilatatum, total lignin content increased through development with the percentage of H-lignin remaining constant but that of S- and G-lignin increasing five- and two-fold respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the putative CCR1 predicted proteins isolated from P. dilatatum in this study are closely related to CCR1 proteins involved in lignin deposition from other monocotyledonous plants, including those from wheat and L. perenne. The complete genomes of the monocotyledons Z. mays, O. sativa and B. distachyon all encode additional CCR proteins that resolved outside of the clade containing the CCR1 predicted proteins from P. dilatatum (Fig. 2). These include a protein annotated as CCR2 from T. aestivum (59805044) (Fig. 2). It is therefore likely that the P. dilatatum genome encodes CCR proteins additional to those described in this study.

Using primers designed to detect the three full length cDNAs isolated from P. dilatatum, it was found that transcripts of PdCCR1 were most abundant in tissues undergoing active lignification (R1, internodes two and three) and were less abundant in tissues such as R2 stage internodes and V stage leaf blades (Fig. 3) in which lignin had already accumulated. These observations are consistent with the idea that CCR1 is involved in constitutive lignification. This is similar to results reported for other species including L. perenne (Tu et al. 2010) and Leucaena leucocephala (Sirvastava et al. 2011).

Transgenic technologies have been widely used over the last decade to modify lignin content and composition in various model plants and crop species. Down-regulation of CCR in species such as N. tabacum (Piquemal et al. 1998; Ralph et al. 1998; Chabannes et al. 2001; O’Connell et al. 2002; Dauwe et al. 2007), S. lycopersicum (Van der Rest et al. 2006) M. sativa (Jackson et al. 2008), A. thaliana (Goujon et al. 2003) and L. perenne (Tu et al. 2010), has generally resulted in a reduction in lignin content. A reduction of lignin content, in particular large reductions of more than 30 %, have been associated with phenotypic abnormalities such as a reduction in plant size (Piquemal et al. 1998; Ralph et al. 1998; Chabannes et al. 2001; Goujon et al. 2003; Van der Rest et al. 2006; Dauwe et al. 2007; Prashant et al. 2011), delayed senescence (Mir Derikvand et al. 2008), delayed flowering (Prashant et al. 2011) and retarded seed development (Jones et al. 2001) or compromised pathogen defence (Prashant et al. 2011). These deleterious phenotypes infer that a very large reduction in lignin content is incompatible with normal growth and plant development. This suggests that there may be an optimal level to which lignin can be decreased for enhanced digestibility without an adverse effect on plant growth. P. dilatatum plants in which CCR was down-regulated showed no obvious deleterious developmental phenotypes compared to non-transgenic control plants when grown in standard glasshouse conditions. A moderate reduction in total lignin content (up to 20 %) was achieved in leaf blades. A decrease in levels of guaiacyl (G) subunits (up to 37 %) was observed in leaf blades, leading to an increase in the S/G ratio since syringyl (S) and hydroxyphenyl (H) subunit levels were not affected. These changes in composition are consistent with those observed in the ZmCCR1 − mutant of Z. mays which showed only a 10 % reduction in lignin content while the S/G ratio increased (Tamasloukht et al. 2011).

In addition to changes in lignin composition, concentrations of p-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid and sinapic acid were observed to increase in the transgenic P. dilatatum lines. Similar results were observed in L. perenne transgenic lines (Tu et al. 2010) as well as in lignin-modified N. tabacum plants (Chabannes et al. 2001; Dauwe et al. 2007; Prashant et al. 2011), P. tremula × P. alba (Leplé et al. 2007) and A. thaliana (Goujon et al. 2003; Mir Derikvand et al. 2008). This increase indicates that metabolic intermediates have been re-directed into other pathways such as flavonoid biosynthesis, presumably as a result of reduced flux from coumaroyl-CoA, caffeoyl-CoA, and feruloyl-CoA to H- G-, and S- lignin (Leplé et al. 2007; Tu et al. 2010).

Our results suggest that PdCCR1 is involved in monolignol formation, most notably the production of G-lignin subunits. NIRS analysis estimated that a moderate reduction in total lignin and an increase in the S/G ratio correlate with an increase in digestibility. Similar results were also observed in the ZmCCR1 − Z. mays mutant where cell wall digestibility improved by 24–28 % with only a 10 % reduction in lignin content (Tamasloukht et al. 2011).

The production of low-lignin C4 grasses with enhanced digestibility is desirable for the forage industry where they are considered more vigorous alternatives to temperate forage species and may increase milk production in the expanding tropical and warm temperate regions (Li et al. 2008; Seidel et al. 2008; Hisano et al. 2009). Engineering of C4 grasses with enhanced digestibility may also provide additional substrates for the cellulosic biofuel production industry. While further experiments are required to identify additional PdCCR gene family members, to investigate their roles and to isolate and characterise other enzymes in the lignin-biosynthesis pathway, it is clear that down-regulation of CCR1 is an effective strategy for the production of C4 forage grasses with decreased lignin content. Future studies will remove the selectable marker cassette by molecular breeding and assess the growth, fertility and agronomic performance of P. dilatatum germplasm with enhanced digestibility due to modification of lignin biosynthesis under field conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Noel Cogan, Matthew Hayes and Daniel Isenegger for critical reading of the manuscript; Gustavo Schrauf from Facultad de Agronomía de la Universidad de Buenos Aires (FAUBA) for kind provision of P. dilatatum cv. Primo; Noel Cogan for advice with identification of CCR transcripts; Maiko Nakajima and Helen Huxley for purification of transgene cassette DNA; Roovini Weerasinghe for assistance with tissue culture; Pippa Kay for advice with quantitative real time PCR assays; Suzan Georges for advice on Southern hybridisation protocols; Carly Elliott for NIRS scanning and Larry Jewell, Alix Malthouse and Darren Callaway for growth and maintenance of all plants used in this study. This work was funded by the Dairy Futures Cooperative Research Centre, Australia. German Spangenberg and Aidyn Mouradov are inventors on US patent 2010/028766, ‘Modification of Lignin Biosynthesis Via Sense Suppression’.

References

- Akin DE. Histological and physical factors affecting digestibility of forages. Agron J. 1989;81:17–25. doi: 10.2134/agronj1989.00021962008100010004x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anterola A, Lewis N. Trends in lignin modification: a comprehensive analysis of the effects of genetic manipulations/mutations on lignification and vascular integrity. Phytochem. 2002;61:221–294. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00211-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj S, Ran Y, Phillips J, Kularajathevan G, Pal S, Cohen D, Elborough K, Puthigae S. A high throughput Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation method for functional genomics of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25:651–659. doi: 10.1007/s00299-005-0099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baréa K, Scheffer-Basso SM, Dall’Agnol M, Oliveira BN. Management of Paspalum dilatatum Poir. biotype Virasoro. 1. Production, chemical composition and persistence. R Bras Zootec. 2007;36:992–999. doi: 10.1590/S1516-35982007000500002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrière Y, Argillier O, Chabbert B, Tollier MT, Monties B. Breeding silage maize with brown-midrib genes. Feeding value and biochemical characteristics. Agronomie. 1994;13:865–876. doi: 10.1051/agro:19931001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baucher M, Monties B, Van Montagu M, Boerjan W. Biosynthesis and genetic engineering of lignin. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1998;17:125. doi: 10.1016/S0735-2689(98)00360-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard-Vailh MA, Mign C, Cornu A, Maillot MP, Grenet E. Effect of modification of the O-methyltransferase activity on cell wall composition, ultrastructure and degradability of transgenic tobacco. J Sci Food Agric. 1996;72:385–391. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199611)72:3<385::AID-JSFA664>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton D, Russell JR. Lignin constituents and cell-wall digestibility of grass and legume stems. Crop Sci. 1988;28:553–558. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1988.0011183X002800030026x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casa AM, Mitchell SE, Lopes CR, Valls JFM. RAPD analysis reveals genetic variability among sexual and apomictic Paspalum dilatatum Poiret Biotypes. J Hered. 2002;93:300–302. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casler MD, Vogel KP. Accomplishments and impact from breeding for increased forage nutritional value. Crop Sci. 1999;39:12–20. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1999.0011183X003900010003x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chabannes M, Barakate A, Lapierre C, Marita JM, Ralph J, Pean M, Danoun S, Halpin C, Grima-Pettenati J, Boudet AM. Strong decrease in lignin content without significant alteration of plant development is induced by simultaneous down-regulation of cinnamoyl CoA reductase (CCR) and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) in tobacco plants. Plant J. 2001;28:257–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Auh C, Chen F, Cheng X, Aljoe H, Dixon RA, Wang Z. Lignin deposition and associated changes in anatomy, enzyme activity, gene expression, and ruminal degradability in stems of tall fescue at different developmental stages. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:5558–5565. doi: 10.1021/jf020516x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Auh C, Dowling P, Bell J, Lehmann D, Wang Z. Transgenic down-regulation of caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) led to improved digestibility in tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) Funct Plant Biol. 2004;31:235–245. doi: 10.1071/FP03254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BG, Pengelly BC, Brown SD, Donnelly JL, Eagles DA, Franco MA, Hanson J, Mullen BF, Partridge IJ, Peters M, Schultze-Kraft R (2005) Tropical forages: an interactive selection tool (CSIRO, DPI&F(Qld), CIAT and ILRI, Brisbane) http://www.tropicalforages.info

- Costa MA, Collins RE, Anterola A, Cochrane F, Davin L, Lewis N. An in silico assessment of gene function and organization of the phenylpropanoid pathway metabolomic networks in Arabidopsis thaliana and limitations thereof. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:1097–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00517-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauwe R, Morreel K, Goeminne G, Gielen B, Rohde A, Van Beeumen J, Ralph J, Boudet AM, Kopka J, Rochange SF, Halpin C, Messens E, Boerjan W. Molecular phenotyping of lignin-modified tobacco reveals associated changes in cell-wall metabolism, primary metabolism, stress metabolism and photorespiration. Plant J. 2007;52:263–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Escamilla-Treviño L, Shen H, Uppalapati S, Ray T, Tang Y, Hernandez T, Yin Y, Xu Y, Dixon R. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) possesses a divergent family of cinnamoyl CoA reductases with distinct biochemical properties. New Phytol. 2010;185:143–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AJ, Neudoerffer TS. Chemical and in vivo evaluation of a brown midrib mutant of Zea mays. I. Fibre, lignin and amino acid composition and digestibility for sheep. J Sci Food Agric. 1973;24:565–577. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740240510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon T, Ferret V, Mila I, Pollet B, Ruel K, Burlat V, Joseleau J, Barriere Y, Lapierre C, Jouanin L. Down-regulation of the AtCCR1 gene in Arabidopsis thaliana: effects on phenotype, lignins and cell wall degradability. Planta. 2003;217:218–228. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-0987-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabber JH. How do lignin composition, structure, and cross-linking affect degradability. A review of cell wall model studies. Crop Sci. 2005;45:820–831. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2004.0191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumie S, Goffner D, Barbier O, Martinant JP, Pichon M, Barrière Y. Expression of cell wall related genes in basal and ear internodes of silking brown-midrib-3, caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) down-regulated and normal maize plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo DJ, Chen F, Inoue K, Blount JW, Dixon RA. Downregulation of caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase and caffeoyl CoA 3-O-methyltransferase in transgenic alfalfa: impacts on lignin structure and implications for the biosynthesis of G and S lignin. Plant Cell. 2001;13:73–88. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin C, Knight M, Foxon G, Campbell BD, Chabbert B, Tollier MT, Schuch W. Manipulation of lignin quality by downregulation of cinnamoyl alcohol dehydrogenase. Plant J. 1994;6:339–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.06030339.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano N, Nandakumar R, Wang Z. Genetic modification of lignin biosynthesis for improved biofuel production. In vitro cellular and developmental biology. Plant. 2009;45:306–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton EM, Nelson CJ (1968) Plant breeding and genetics. In: CSIRO TSotCL (ed) Some concepts and methods in sub-tropical pasture research. CSIRO, Brisbane, Australia

- Iiyama K, Wallis AFA. Determination of lignin in herbaceous plants by an improved acetyl bromide procedure. J Sci Food Agric. 1990;51:145–161. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740510202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L, Shadle G, Zhou R, Nakashima J, Chen F, Dixon R. Improving saccharification efficiency of alfalfa stems through modification of the terminal stages of monolignol biosynthesis. BioEnergy Res. 2008;1:180–192. doi: 10.1007/s12155-008-9020-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Ennos AR, Turner SR. Cloning and characterization of irregular xylem4 (irx4): a severely lignin-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2001;26:205–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HG, Allen MS. Characteristics of plant cell walls affecting intake and digestibility of forages by ruminants. J Animal Sci. 1995;73:2774–2790. doi: 10.2527/1995.7392774x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HG, Deetz DA (1993) Cell wall lignification and degradability. In: Jung H, Buxton D, Hatfield R, Ralph J (eds) Forage cell wall structure and digestibility. Am Soc Agron, Madison, WI, pp 315–346

- Jung HG, Vogel KP. Influence of lignin on digestibility of forage cell wall material. J Animal Sci. 1986;62:1703–1712. doi: 10.2527/jas1986.6261703x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Koita H, Nakatsubo T, K H, Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Umemura K, Yumezawa T, Shimamoto K. Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in lignin biosynthesis, is an effector of small GTPase Rac in defense signaling in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:230–235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509875103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe E, Simon H, Doorsselaere JV, Piquemal J, Goffner D, Poeydomenge O, Boudet A-M, Grima-Pettenati J. Cinnamoyl CoA reductase, the first committed enzyme of the lignin branch biosynthetic pathway: cloning, expression and phylogenetic relationships. Plant J. 1997;11:429–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11030429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K. Molecular cloning and characterization of cDNA encoding sinnamoyl CoA reductase (CCR) from barley (Hordeum vulgare) and potato (Solanum tuberosum) J Plant Physiol. 2004;161:105–112. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauvergeat V, Lacomme C, Lacombe E, Lasserre E, Roby D, Grima-Pettenati J. Two cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) genes from Arabidopsis thaliana are differentially expressed during development and in response to infection with pathogenic bacteria. Phytochemistry. 2001;57:1187–1195. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00053-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leplé J-C, Dauwe R, Morreel K, Storme V, Lapierre C, Pollet B, Naumann A, Kang K-Y, Kim H, Ruel K, Lefebvre A, Joseleau J-P, Grima-Pettenati J, De Rycke R, Andersson-Gunneras S, Erban A, Fehrle I, Petit-Conil M, Kopka J, Polle A, Messens E, Sundberg B, Mansfield SD, Ralph J, Pilate G, Boerjan W. Downregulation of cinnamoyl-Coenzyme A reductase in poplar: multiple-level phenotyping reveals effects on cell wall polymer metabolism and structure. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3669–3691. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kajita S, Kawai S, Katayama Y, Morohshi N. Down-regulation of an anionic peroxidase in transgenic aspen and its effect on lignin characteristics. J Plant Res. 2003;116:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Weng JK, Chapple C. Improvement of biomass through lignin modification. Plant J. 2008;54:569–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SY, Dence CW (1992) Methods in lignin chemistry. Springer, Berlin, Germany

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QH, Tian B. Biochemical characterization of a cinnamoyl-CoA reductase from wheat. J Biol Chem. 2005;386:553–560. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP and Maddison DR (2011) Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.75 http://mesquiteproject.org

- McElroy D, Zhang W, Cao J, Wu R. Isolation of an efficient actin promoter for use in rice transformation. Plant Cell. 1990;2:163–171. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir Derikvand M, Sierra JB, Ruel K, Pollet B, Do CT, Thevenin J, Buffard D, Jouanin L, Lapierre C. Redirection of the phenylpropanoid pathway to feruloyl malate in Arabidopsis mutants deficient for cinnamoyl-CoA reductase 1. Planta. 2008;227:943–956. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell A, Holt K, Piquemal J, Grima-Pettenati J, Boudet A. Improved paper pulp from plants with suppressed cinnamoyl-CoA reductase or cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase. Transgenic Res. 2002;11:495–503. doi: 10.1023/A:1020362705497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S-H, Mei C, Pauly M, Ong RG, Dale BE, Sabzikar, R, Fotoh H, Nguyen T, Sticklen M (2012) Downregulation of maize cinnamoyl-coenzyme A reductase via RNA interference technology causes brown midrib and improves ammonia fiber expansion-pretreated conversion into fermentable sugars for biofuels. Crop Sci 52:2687–2701

- Pichon M, Courbou I, Beckert M, Boudet AM, Grimapettenati J. Cloning and characterization of two maize cDNAs encoding cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) and differential expression of the corresponding genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:671–676. doi: 10.1023/A:1006060101866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquemal J, Lapierre C, Myton K, O’Connell A, Schuch W, Grima-Pettenati J, Boudet AM. Down-regulation of cinnamoyl-CoA reductase induces significant changes of lignin profiles in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant J. 1998;13:71–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00014.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piquemal J, Chamayou S, Nadaud I, Beckert M, Barrire Y. Down-regulation of caffeic acid O-methyltransferase in maize revisited using a transgenic approach. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:1675–1685. doi: 10.1104/pp.012237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashant S, Srilakshmi Sunita M, Pramod S, Ranadheer K, Gupta K, Anil Kumar S, Rao Karumanchi S, Rawal SK, Kavi Kishor PS. Downregulation of Leucaena leucocephala cinnamoyl CoA reductase (LiCCR) gene induces significant changes in phenotype, soluble phenolic pools and lignin in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;12:2215–2231. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph J, Hatfield RD, Piquemal J, Yahiaoui N, Pean M, Lapierre C, Boudet AM. NMR characterization of altered lignins extracted from tobacco plants down-regulated for lignification enzymes cinnamylalcohol dehydrogenase and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12803–12808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DL, Wheat KG, Hubbert NL, Henderson M, Savoy HJ. Dallisgrass yield, quality and nitrogen recovery responses to nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1988;19:529–542. doi: 10.1080/00103628809367957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LA, Campbell MM. The genetic control of lignin deposition during plant growth and development. New Phytol. 2004;164:17–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolando C, Monties B, Lapierre C. Thioacidolysis. In: Stephen SY, Dence CW, editors. Methods in lignin chemistry. Heidelberg: Springer; 1992. pp. 334–349. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel DJ, Fu Q, Randel WJ, Reichler TJ. Widening of the tropical belt in a changing climate. Nat Geosci. 2008;1:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira ED, Alves-Ferreira M, Guimaraes LA, Rodriguez da Silva F, Campos Carneiro V. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR expression studies in the apomictic and sexual grass Brachiaria brizantha. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirvastava S, Gupta K, Arha M, Vishwakarma K, Rawal SK, Kavi Kishor PB, Khan BM. Expression analysis of cinnamoyl-CoA rreductase (CCR) gene in developing seedlings of Leucaena leucocephala: a pulp yielding tree species. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2011;49:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KF, Simpson RJ, Oram RN, Lowe KF, Kelly KB, Evans PM, Humphreys MO. Seasonal variation in the herbage yield and nutritive value of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) cultivars with high or normal herbage water-soluble carbohydrate concentrations grown in three contrasting Australian dairy environments. Aust J Exp Agric. 1998;38:821–830. doi: 10.1071/EA98064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamasloukht B, Wong Quai Lam MS, Martinez Y, Tozo K, Barbier O, Jourda C, Jauneau A, Borderies G, Balzergue S, Renou JP, Huguet S, Martinant JP, Tatout C, Lapierre C, Barriere Y, Goffner D, Pichon M. Characterization of a cinnamoyl-CoA reductase 1 (CCR1) mutant in maize: effects on lignification, fibre development, and global gene expression. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:3837–3848. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Takamatsu S, Nojiri C, Ooba S, Anzai H, Iwata M, Christensen AH, Quail PH, Uchimiya H. Expression of a maize ubiquitin gene promoter-bar chimeric gene in transgenic rice plants. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1503–1507. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y, Rochfort S, Liu Z, Ran Y, Griffith M, Badenhorst P, Louie G, Bowman M, Smith K, Noel J, Mouradov A, Spangenberg G. Functional analysis of Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase and cinnamoyl-CoA-reductase genes from perennial reygrass (Lolium perenne) Plant Cell. 2010;22:3357–3373. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Rest B, Danoun S, Boudet A-M, Rochange SF. Down-regulation of cinnamoyl-CoA reductase in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) induces dramatic changes in soluble phenolic pools. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:1399–1411. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR (1993) Organisation of forage plant tissues. In: Jung H (ed) Forage cell wall structure and digestibility, American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America, Madison, WI, pp 1–32

- Wilson JR. Cell wall characteristics in relation to forage digestion by ruminants. J Agric Sci. 1994;122:173–182. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600087347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Jackson L, Shadle G, Nakashima J, Temple S, Chen F, Dixon R. Distinct cinnamoly CoA reductases involved in parallel routes to lignin in Medicago truncatula. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;41:17803–17808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.