Abstract

Tissue fibrosis occurs as a result of the dysregulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis. Tissue fibroblasts, resident cells responsible for the synthesis and turnover of ECM, are regulated via numerous hormonal and mechanical signals. The release of intracellular nucleotides and their resultant autocrine/paracrine signaling have been shown to play key roles in the homeostatic maintenance of tissue remodeling and in fibrotic response post-injury. Extracellular nucleotides signal through P2 nucleotide and P1 adenosine receptors to activate signaling networks that regulate the proliferation and activity of fibroblasts, which, in turn, influence tissue structure and pathologic remodeling. An important component in the signaling and functional responses of fibroblasts to extracellular ATP and adenosine is the expression and activity of ectonucleotideases that attenuate nucleotide-mediated signaling, and thereby integrate P2 receptor- and subsequent adenosine receptor-initiated responses. Results of studies of the mechanisms of cellular nucleotide release and the effects of this autocrine/paracrine signaling axis on fibroblast-to-myofibroblast conversion and the fibrotic phenotype have advanced understanding of tissue remodeling and fibrosis. This review summarizes recent findings related to purinergic signaling in the regulation of fibroblasts and the development of tissue fibrosis in the heart, lungs, liver, and kidney.

Keywords: fibrosis, purinergic, P2X, P2Y, ATP, adenosine

the synthesis and turnover of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is essential for normal tissue organization and function, both during development and adaptive homeostasis, as well as in the tissue remodeling that occurs after injury. As described in detail in other articles in this Theme series and Call for Papers (6, 6a, 53, 88, 95, 142), tissue fibroblasts are the predominant cell type responsible for the generation, maintenance, and degradation of the ECM. Excessive or abnormal signaling by growth factors, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and angiotensin II (ANG II), which stimulate fibroblast proliferation, migration, and profibrogenic activity, typically underlies the development of tissue fibrosis (21, 86, 110). TGF-β and ANG II stimulate the synthesis of collagens and other matrix proteins, increase expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), a contractile protein and hallmark of profibrogenic fibroblast activation, and increase the expression of numerous profibrotic markers (Table 1), which include plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, also known as CCN2, a member of the Cyr61, CTGF, Nov family of cysteine-rich matricellular secreted proteins), interleukin-6 and monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 (2, 52, 110). In addition to the well-known profibrotic roles of TGF-β and ANG II, recent work has implicated extracellular nucleotides as important autocrine/paracrine signals that regulate fibroblast homeostasis.

Table 1.

Common genes/proteins involved in tissue fibrosis

| Gene | Expression (↑ or ↓) in Fibrotic Tissues |

|---|---|

| α-Smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) | ↑ (63) |

| Collagen I | ↑ (8, 20) |

| Fibronectin | ↑ (31) |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 | ↑ (52, 111) |

| Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) | ↑ (70) |

| Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β | ↑ (17, 86, 115) |

| Cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61/CCN1) | ↑ (70) |

| Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) | ↑ (36, 96) |

| Lysyl oxidase (LOX) | ↑ (91) |

| Periostin | ↑ (87) |

| Monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 | ↑ (35) |

| Interleukin (IL)-6 | ↑ (46) |

| IL-33 | ↑ (73, 147) |

| sST-2 | ↑ (73, 147) |

| Thrombospondin-1 | ↑ (137) |

| Relaxin | ↑ (118, 143) |

| Epac1 | ↓ (140) |

| Snail | ↑ (133) |

| Slug | ↑ (133) |

References shown in parentheses.

Extracellular Adenosine Triphosphate and Other Nucleotides As Signaling Molecules

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the ubiquitous source of energy in cells, achieves typical intracellular concentrations in the low millimolar range (58). In addition, ATP can be released from cells and then impact on cellular signaling and function. Burnstock was the first to show the release of ATP in his studies of nerves in the autonomic nervous system (125), yet 40 years later the precise roles for ATP and other extracellular nucleotides in signal transduction and cell regulation are still not fully understood. It is clear, however, that signaling by extracellular nucleotides plays important roles in virtually all tissues and organ systems (18, 139).

What is generally termed the “purinergic signaling” cascade is initiated by the release of cellular nucleotides from intracellular vesicles or the cytoplasm (139). Studies examining the pericellular space of airway epithelial cells have detected ATP in nanomolar concentrations around resting cells, but physical stimulation can increase pericellular ATP concentrations up to ∼1,000-fold (9, 104), concentrations sufficient to activate nucleotide receptors on the cell surface (1, 41, 85).

The release of nucleotides and the downstream signaling that results from the activation of plasma membrane nucleotide receptors on the cells from which nucleotides are released or on nearby cells can produce autocrine or paracrine effects, respectively, that alter cell and tissue homeostasis. Such effects include helping to establish the basal “set points” of signal transduction and functional activities (33, 93, 106). An important response influenced by nucleotide signaling that has garnered substantial recent interest is the regulation of tissue remodeling and, in pathological states, of tissue fibrosis. This review will discuss nucleotide release and the receptors that mediate its signaling, and in particular, the effects of purinergic signaling on fibroblasts and tissue fibrosis.

Mechanisms of ATP Release: Implications For the Regulation of Fibrosis

Mechanisms for cellular nucleotide release have been the subject of a number of comprehensive reviews (19, 33, 84, 85, 89, 128). Here, we briefly summarize the pathways relevant to tissue remodeling and fibrosis.

Tissue injury can trigger damage to the plasma membrane, apoptosis, or necrosis, all of which can lead to the release of intracellular ATP and other nucleotides (e.g., UTP, ADP, UDP), which can initiate the recruitment of inflammatory cells, such as polymorphonuclear neutrophils and macrophages, as well as platelet aggregation (26, 41, 66). Such findings have provided evidence that ATP released in response to cell injury is a chemotactic signal involved in wound repair and resolution as well as scar formation.

Aside from cell damage-promoted release of nucleotides, gap junction channels have been identified as a major route of cellular ATP release. Connexins (Cxs) are a family of plasma membrane-spanning proteins that form hexameric oligomers (connexons) constituting one-half of a gap junction channel (56, 89, 117). Relatively nonselective transport of signaling molecules of <1 kDa in size can occur through these hemichannels (89), which form a ∼1.4–1.8 nM diameter pore through which intracellular molecules can pass into the pericellular and extracellular spaces (80, 120).

Similar to Cxs, the pannexin (Panx) family are membrane-spanning proteins consisting of three isoforms, Panx-1, -2, and -3, which are thought to share functional homology with Cx proteins (107). Panx-1, which is expressed in most tissues, is the best understood of the three isoforms and has been implicated in the formation of hemichannels that can function as major conduits of ATP release (107). While understanding of the gating mechanisms of Cx and Panx hemichannels is incomplete, they include changes in membrane potential, low extracellular Ca2+ concentrations as well as mechanical stimulation that can promote hemichannel opening (7, 54, 117, 126).

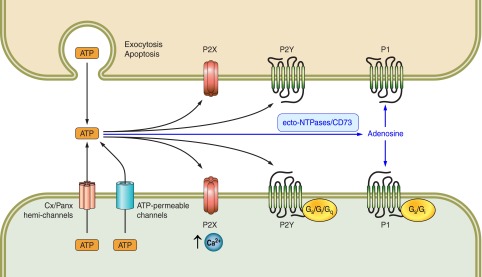

Together, these various mechanisms of ATP release initiate an autocrine/paracrine signaling cascade that can regulate the fibrotic tone and cellular response of tissue fibroblasts. This profibrotic signaling axis occurs in several organs, including the heart (13, 94, 101), lung (12, 113), kidney (21), and liver (95, 128). These ATP-initiated signaling pathways involve the activation of a diverse family of nucleotide receptors (to be described in the next section). Furthermore, hydrolysis of ATP to adenosine, a reaction catalyzed by cell surface enzymes (33, 139, 148), activates adenosine receptors, adding further complexity to the mechanisms controlling cellular homeostasis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Nucleotide and adenosine receptor-mediated signaling pathways activated in response to cellular nucleotide (e.g., ATP) release.

Nucleotide Receptors: Role in Tissue Fibroblasts

There are two types of nucleotide receptors: P2X and P2Y receptors. Expressed in nearly all mammalian tissues, the P2X receptors are ATP-gated ion channels of which there are seven subtypes, P2X1–7 (16, 82, 102). P2X receptor subunits are composed of two transmembrane domains, a single extracellular loop and intracellular amino- and carboxy-termini. Association of the subunits to form a trimer generates a functional P2X receptor (77). The affinity of P2X receptors for ATP and ATP-derived analogs is in the low micromolar range; other nucleotides or adenosine bind weakly or not at all (71, 78). ATP binding to P2X receptors opens their nonselective channel, allowing the passage of monovalent and divalent cations. As a consequence, membrane potential changes and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations increase, leading to the stimulation of Ca2+-dependent intracellular signaling pathways (71, 78).

The P2Y receptor subfamily consists of eight 7-transmembrane/G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that respond to a variety of extracellular nucleotides and have distinct patterns of coupling to different heterotrimeric G proteins. Unlike P2X receptors that show exquisite selectivity for ATP as their physiologic agonist, various P2Y receptors respond to both ATP and other nucleotides (e.g., P2Y2 to UTP) or preferentially to nucleotides other than ATP (Table 2). The Gq-coupled P2Y receptors, P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, and P2Y11, signal via the phospholipase C pathway and its products diacylglycerol and inositol triphosphate, which activate protein kinase C and increase intracellular Ca2+, respectively (129). P2Y11 is the only P2Y receptor that couples to Gs and activates adenylyl cyclase (AC), whereas the remaining P2Y receptors couple to Gi and inhibit AC activity (129). The role of β-arrestins in the signaling and responses of P2Y receptors is not well defined (64, 98, 119).

Table 2.

P2Y receptors, their preferred ligands, and G protein coupling

| P2Y Receptor | Preferred Ligand (EC50, µM) | Coupling |

|---|---|---|

| P2Y1 | ADP (1) > ATP (4) | Gq |

| P2Y2 | UTP (0.14) ≈ ATP (0.23) | Gq |

| P2Y4 | UTP (2.5) [rodent: UTP (2.6) ≈ ATP (1.8)] | Gq |

| P2Y6 | UDP (0.300) > UTP (6) > ADP (30) | Gq |

| P2Y11 | ATP (17.4) | Gq/Gs |

| P2Y12 | ADP (60.7) | Gi |

| P2Y13 | ADP (60) > ATP (261) | Gi |

| P2Y14 | UDP-glucose (80) > UDP-galactose (124) | Gi |

The P2 receptor subtype(s) that mediate fibrotic responses vary among tissues and cell types. Owing to tissue-specific receptor expression, subtype-specific ligand binding and, possibly, restricted membrane localization (72, 108, 127), the net effect of P2 receptor activation is likely the integration of numerous, parallel signaling pathways.

In the following sections, we describe the contribution of purinergic signaling in the regulation of tissue fibroblasts and the development of fibrosis in several major organ systems (heart, lungs, liver, and kidney).

Heart

In the myocardium, the ECM and collagen lattice, composed primarily of collagen types I and III, are essential for maintaining normal cardiac electrical conductance, myocyte contraction, and myocardial integrity (8, 43). Cardiac fibrosis leads to decreased myocardial compliance, arrhythmias, diastolic dysfunction, and accompanying heart failure (34).

ATP, ADP, UTP, and UDP can be released from endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, and fibroblasts in the heart following myocardial infarction (83, 132), vascular shear forces (83), hypoxia (30, 37, 50), and pressure overload (101). The released nucleotides act extracellularly to regulate cardiomyocyte hypertrophic responses and to promote fibroblast activity.

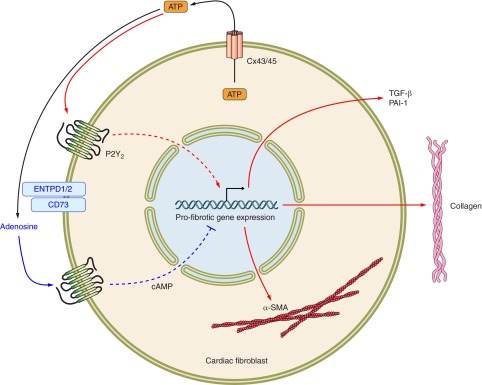

Cx and Panx hemichannels play a major role in nucleotide release in the heart. The release of ATP and UDP by mouse cardiomyocytes subjected to mechanical stretch occurs via Panx-1 hemichannels (101). Such release can stimulate the transformation of fibroblasts to activated (profibrogenic) myofibroblasts via paracrine ATP signaling (37, 101). We have shown that ATP is released from adult rat cardiac fibroblasts by hypotonic challenge (which likely produces mechanical stretching of the plasma membrane), a response that depends on Cx-43 and Cx-45 hemichannels (93, 94).

The fate of released ATP includes its binding and autocrine/paracrine activation of P2Y receptors on cardiac fibroblasts (65, 99, 100). P2Y2 receptors are highly expressed in adult rat ventricular cardiac fibroblasts (121), and activation of these receptors by ATP and UTP is strongly profibrotic, in terms of increasing synthesis of ECM proteins and of many of the genes and proteins associated with a profibrogenic phenotype (Table 1) (14, 37, 93, 94). P2Y2 receptors have an important role in the homeostasis of cardiac fibroblasts: constitutive P2Y2 signaling contributes to the establishment of the “set point” of fibrotic activity in cardiac fibroblasts (33, 93). In addition to P2Y2 receptors, ATP activates P2X4 and P2X7 receptors on cardiac fibroblasts to stimulate cell proliferation in an Akt and ERK1/2-dependent manner (25).

Profibrotic effects from UDP-mediated activation of P2Y6 receptors have been described by Nishida et al. (97). Activation of P2Y6 receptors by the autocrine/paracrine release of UDP initiates a fibrotic response that involves the upregulation of CTGF, TGF-β, periostin, and other profibrogenic factors. Treatment with apyrase, which hydrolyzes extracellular nucleotides, strongly reduces basal fibrogenic activity of cardiac fibroblasts (94). Moreover, the enhanced release of cellular nucleotides in pathologic conditions, such as pressure or volume overload, ischemia, hypoxia, or myocardial infarction, may help trigger fibrotic response in the myocardium. Thus, acute increases in interstitial nucleotide concentration following cardiac injury may contribute to remodeling and wound healing responses following myocardial infarction, as well as being a possible mechanism, which when dysregulated, leads to cardiac fibrosis (i.e., excessive scarring and stiffness) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ATP released by cardiac fibroblasts initiates counterbalancing pro- and antifibrotic signals mediated by ATP and adenosine, respectively.

Lung

Several different types of fibrosis occur in the lungs. These include fibrotic changes in the interstitium that is located between alveolae, airways, and vascular components, as well as fibrotic changes that can occur in the airways and in pulmonary vessels. Inflammatory events can contribute to fibrotic lung disease, but the role of inflammation is controversial (136). The greatest extent of fibrosis in humans occurs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a disease of unknown etiology and for which there is a lack of effective therapies (6a, 47, 92, 136). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of patients with IPF contains a higher concentration of ATP than does BAL fluid from control subjects; similarly, BAL fluid from mice whose airways are treated with bleomycin (an agent used to induce a model of pulmonary fibrosis) has a higher ATP concentration than does BAL fluid from control animals (113). Treatment with ATPγS enhances and with apyrase reduces inflammatory cell recruitment of bleomycin-treated mice. Lung inflammation, expression of fibrotic markers, and collagen content are lower in P2X7 receptor-deficient than in wild-type (WT) mice treated with bleomycin, thus implicating ATP release from bleomycin-injured lung cells as a “danger signal” that acts via P2X7 receptors to promote lung fibrosis (113). Other data suggest that PKC-β1 may contribute to the action of calcium and P2X7 receptors in airway epithelial cells and promote fibrosis in the bleomycin model (12). Inflammation in the lung can also induce release of ATP from airway epithelial cells; this release appears to occur by calcium-dependent vesicular mechanisms but not via Panx-1 (105).

Information regarding purinergic receptors in the lungs has been recently reviewed (19). Direct evidence for the presence of purinergic receptors in lung fibroblasts has been most clearly shown in studies of fibroblasts grown in explant cultures of excised lung parenchyma from WT mice and mice that have a knockout of P2Y2 receptors (65): In fibroblasts of WT mice, nucleotides (with a rank-order of potency: UTP >/= ATP >> ADP > UDP) increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration and inositol phosphate generation from phosphoinositides, responses that are absent in fibroblasts of P2Y2-knockout mice. P2Y2 thus appears to be the only functionally expressed nucleotide receptor in mouse lung fibroblasts. In human pulmonary fibroblasts, activation of P2Y receptors (by ATP, ADP, or UTP) increases calcium waves through ryanodine-insensitive channels and can enhance the expression of P2Y4 receptors, TGF-β, collagen A1, and fibronectin (68).

Studies with a different type of lung fibroblast, i.e., adventitial fibroblasts from the bovine lung pulmonary artery, have shown that acute hypoxia (3% O2) induces a ∼2-fold increase in the release of ATP within 10 min, that persistent increases in ATP release last at least 24 h, and that chronic hypoxia (for 14 to 30 days) attenuates extracellular ATP hydrolysis by ectonucleotidase(s) (50, 123). In addition, those investigators found that ATP, UTP, ADP-βS, and MeSATP increase [3H]thymidine incorporation in fibroblasts, a response that is additively increased by hypoxia. Hypoxia promotes the conversion of adventitial fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. In addition, ATP and/or hypoxia synergistically increases mitogen-induced DNA synthesis but P2 receptor antagonists [suramin, cibacron blue 3G-A, and pyridoxal phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,-4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS)] and apyrase (the nucleotide hydrolytic enzyme) attenuate ATP and hypoxia-induced DNA synthesis. Such findings suggest that P2 receptor activation by hypoxia may result from the release of endogenous ATP. ATP and hypoxia induce the expression and activation of the Egr-1 transcription factor and stimulate proliferation of adventitial fibroblasts via a mechanism that appears to involve multiple signaling components, including Gαi, PI3K, Akt, mTOR, p70 S6kinase, and ERK1/2 (51). Taken together [and as recently reviewed (124)], such data imply that hypoxia in the lung enhances the growth of adventitial fibroblasts and their transformation to myofibroblasts through the release of ATP, autocrine/paracrine activation of P2 receptors, and altered ATP hydrolysis. Such effects may contribute to the pathophysiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

A key question with respect to ATP and lung fibrosis relates to the precise identity of the nucleotide or metabolic product(s) that promote fibrosis. Substantial work has 1) implicated the ATP hydrolytic product adenosine as being profibrotic for lung fibroblasts and in promoting lung fibrosis in experimental animal models and in patients with IPF or with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and 2) suggested that increased expression of enzymes involved in the generation of adenosine generation from ATP and increased expression of A2B receptors, which may contribute to profibrotic effects of adenosine in the lung, occur in such patients (28, 74, 144–146).

Kidney

Renal fibrosis can lead to deteriorating organ function and eventually to renal failure. While TGF-β and ANG II are major regulators of ECM deposition and profibrotic remodeling in the kidney, there is much evidence that links nucleotide and adenosine signaling to the progression of renal fibrosis.

In the kidney, ATP release can be induced by hypotonic stimulation of tubular epithelial cells (134), sympathetic and adrenergic stimulation of the renal cortex (130), and activation of endothelial and smooth muscle cells (122). Cells in the nephron and renal vasculature express P2Y and P2X receptors that mediate numerous physiological actions, including glomerular pressure and renal vascular tone (11, 109, 112, 122).

Mesangial cells and renal fibroblasts, which are key contributors to the formation of ECM in the kidney, produce collagen, fibronectin, and other matrix proteins in response to TGF-β and ANG II signaling (116, 122). Additionally, activation of P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors on mesangial cells stimulates their proliferation (60), and P2X7 activation increases mesangial cell collagen synthesis (122) and interstitial fibrosis in vivo (55). Solini et al. (122) observed different effects of P2Y and P2X7 receptor activation and reported that UTP-mediated stimulation of P2Y2 receptors inhibits collagen synthesis. This pathway counterbalances P2X7 activation and highlights the contrasting effects that occur with different nucleotides and the responses they promote through activation of various purinergic receptors.

In cardiac fibroblasts, a pronounced upregulation of PAI-1 occurs in response to stimulation of P2Y2 receptors by either ATP or UTP (14, 94). This is notable because PAI-1 upregulation accompanies renal fibrosis and inhibits plasmin activation, thereby blocking the subsequent activation of proteases that degrade ECM (111). PAI-1-knockout mice are resistant to the fibrosis that results from ureteral obstruction, as manifest by less synthesis of collagen, TGF-β, and α-SMA than occurs in control mice (103).

In addition to the action of resident renal fibroblasts and mesangial cells in contributing to renal fibrosis, renal tubular epithelial cells can undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in response to injury, inflammation, and TGF-β signaling (21, 141). The contribution of EMT to renal fibrosis is controversial but has been readily demonstrated in cell culture (81). Cells that have undergone EMT have increased expression of matrix proteins, disrupted epithelial layers, and can be a precursor to pathologic scar formation (21, 67, 141). Limited data have suggested that extracellular nucleotides may promote EMT in renal epithelial cells (135). Adenosine A2A receptor activation has been found to inhibit renal inflammation and fibrosis by attenuating collagen deposition (48) and may also inhibit profibrotic EMT of renal tubular epithelial cells (138). Using the model of unilateral ureteral obstruction to induce renal fibrosis, Xiao et al. (138) have reported that A2A activation suppresses an upregulated expression of α-SMA while restoring expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin.

Liver

Numerous cell types in the liver express purinergic receptors, which can regulate functions that include glycogen metabolism, bile secretion, vascular tone, and hepatic remodeling (128). ATP can be released by hepatocytes via vesicular exocytosis in response to mechanical forces and osmotic stress, resulting in more than a 30-fold increase in extracellular ATP concentrations (44, 49). Furthermore, the release of ATP and other nucleotides by vascular endothelial cells and bile duct epithelial cells can act as a paracrine signal that can activate profibrogenic cells (10).

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) in the perisinusoidal space and portal fibroblasts are the major cell types responsible for ECM synthesis and turnover in the liver (15, 40, 95). The contribution of the P2Y family of nucleotide receptors to liver fibrosis is better understood than that of P2X receptors, about which little is known. P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors are expressed by rat HSCs, which respond to nucleotides, including UDP, by transforming into myofibroblasts that have greater expression of collagen and α-SMA than do resting HSCs (40). Blockade of P2 receptors with PPADS inhibits HSC proliferation and blunts ECM synthesis in a rodent model of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (38). Furthermore, P2Y2 activation stimulates the recruitment of neutrophils into the liver and causes hepatocyte death (5). In keeping with these data, P2Y2-knockout mice are protected from liver damage and necrosis in response to experimentally (concanavalin A)-induced hepatitis or acetaminophen-promoted liver injury (5).

The importance of nucleotide signaling in liver fibrosis has been demonstrated by experiments that have examined the effects of increasing extracellular nucleotide concentrations. Inhibiting the NTPases responsible for the hydrolysis and termination of nucleotide-mediated signaling exacerbates pathological remodeling and fibrosis (69), illustrating the profibrotic consequences of sustained nucleotide signaling (to be described further in the next section).

The hydrolysis of ATP by membrane-bound enzymes is a major source of extracellular adenosine generation and has functional significance in the liver (114). Adenosine A2A receptor activation activates HSCs and stimulates collagen production, promoting hepatic fibrosis (23), while antagonism of those receptors is protective against CCl4− and ethanol-induced liver fibrosis (27). In both primary HSCs and LX-2 cells (a cell line), A2A receptor activation upregulates the synthesis of collagens I and III in a PKA/ERK- and p38 MAPK-dependent manner, respectively (24).

Current evidence suggests that profibrotic nucleotide signaling in the liver involves the activation of both P2 purinergic receptors and P1 adenosine receptors (10, 39). The generation of extracellular adenosine and the subsequent activation of P1 receptors is dependent on the activity of extracellular NTPases, which integrate ATP/ADP and adenosine signaling and their functional consequences (114).

Hydrolysis of Extracellular Nucleotides: Role of NTPases

The lifetime of extracellular nucleotides, hydrolysis of which occurs by endogenously expressed nucleotidases, is another essential factor in the nucleotide signaling cascade. Such nucleotidases not only hydrolyze nucleotides and terminate ATP/UTP-mediated signaling but also can initiate ADP/UDP and adenosine-mediated signaling pathways (139). Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (ENTPDs) are endogenous Ca2+/Mg2+-dependent nucleotidases that hydrolyze tri- and diphosphate nucleotides into their monophosphate forms. Of the eight ENTPD isoforms (ENTPD1–8), four (ENTPD1–3, 8) are cell surface-localized (148). ENTPD-1 and -2 (CD39 and CD39L1, respectively) are the most studied subtypes; ENTPDs have roles in regulating inflammation, platelet activity, and vascular tone (4, 75, 76). Although ENTPDs do not hydrolyze nucleotide monophosphates, the sequential action of membrane-localized 5′-nucleotidases, such as CD73, on AMP, a product of ENTPD action, generates adenosine, which is an agonist for several GPCRs (A1–4 receptors) (22, 29, 32, 148). Increasing evidence indicates that ENTPD activity is an important aspect of P2 signaling in tissue fibrosis that is able to attenuate nucleotide-dependent responses and help initiate adenosine-mediated remodeling pathways (42, 90, 114).

ENTPD activity has been implicated in contributing to cardiac protection postischemia, likely by facilitating the generation of adenosine, which is cardioprotective (79). Köhler et al. (79) demonstrated that ENTPD1-deficient mice or mice treated with an ENTPD inhibitor were more susceptible to ischemic injury, largely as a consequence of impaired generation of adenosine. Conversely, hydrolysis of extracellular ATP with the nucleotidase apyrase increased adenosine generation and reduced infarct size after ischemic insult (79). We recently described the profibrotic effects of inhibiting ENTPD activity in cardiac fibroblasts (93). ENTPD inhibition increased cardiac fibroblast collagen synthesis and α-SMA expression by enhancing nucleotide (P2Y2 receptor) signaling while simultaneously diminishing counterbalancing antifibrotic adenosine-mediated (in particular, A2B receptor) signaling pathways (Fig. 2).

Similar mechanisms may regulate ischemic protection in the kidney. ENTPD1 inhibition decreases adenosine generation by ATP released during renal ischemia, thereby exacerbating ischemic injury (57). Thus, in both the heart and kidney, profibrotic nucleotide signaling and antifibrotic adenosine signaling (which, as noted above, may also blunt EMT of renal epithelial cells) represent dual points of control in the regulation of organ remodeling. These recent findings suggest that ENTPDs play a key role in controlling the extent of fibrosis via their ability to degrade nucleotides and ultimately, lead to the generation of adenosine.

Contrary to what is observed in the heart, adenosine signaling is profibrotic in the lung: adenosine initiates lung inflammation and promotes fibroblast-to-myofibroblast conversion (19). Adenosine and adenosine receptor levels are elevated in patients with asthma and COPD and contribute to pulmonary fibrosis (28). Mice that lack adenosine deaminase, the enzyme that mediates adenosine clearance, have pulmonary inflammation, fibrosis, myofibroblast proliferation, and alveolar damage as a result of chronically elevated adenosine signaling (28). Unlike in the heart and kidney (but more akin to what occurs in the liver), in the lung, activation of both ATP and adenosine receptors appears to contribute to myofibroblast conversion and the development of fibrosis (28, 113).

Although less is known about the roles of ENTPDs in the liver, ENTPD2 activity in liver portal fibroblasts attenuates bile duct epithelial cell proliferation (69). Loss of portal fibroblast ENTPD2 expression increases epithelial cell proliferation, implying the existence of a paracrine mechanism that involves nucleotide signaling and hydrolysis in the regulation of epithelial cell homeostasis (69). ENTPDs may also be involved in HSC and portal fibroblast proliferation and activation, potentially leading to the development of liver fibrosis by perpetuating purinergic signaling pathways (114).

Thus, results from studies in several tissues implicate ENTPD activity as likely an essential regulatory element in the progression and regulation of fibroblast homeostasis, myofibroblast conversion, and tissue remodeling.

Perspectives and Future Directions

Substantial recent progress illustrates the ubiquitous role of extracellular ATP and other nucleotides in regulating a diverse range of responses, which include inflammation (113), neutrophil migration (26), cellular homeostasis (33, 93), and organ remodeling. In most cases the precise receptors and pathways mediating such responses are not fully defined, but it is clear that cellular nucleotide release and subsequent autocrine/paracrine signaling are essential mediators of tissue homeostasis and organ function.

In addition to the systems described here, other data indicate the involvement of signaling by nucleotides and adenosine in the development of dermal fibrosis (45), pancreatic fibrosis (61, 131), and in the proliferation of cancer-associated fibroblasts (59, 62, 97). Thus, the mechanisms underlying organ remodeling may also prove applicable to tumor fibroblast physiology, leading to the production and maintenance of the stroma that surrounds malignant cells. Targeting these fibroblasts may thus provide a novel therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment.

Together, these discoveries highlight the importance of understanding the signaling pathways invoked by extracellular nucleotides and adenosine in the regulation of fibroblasts and tissue fibrosis. It is evident that extracellular nucleotides and adenosine are not simply “innocent bystander” signaling molecules, but instead are integral autocrine/paracrine messengers that have essential roles in tissue homeostasis, normal and pathological organ remodeling, and response to injury. Much is still unknown about this signaling axis, which for each tissue encompasses multiple stimuli and mechanisms of cellular nucleotide release, different subsets of receptors, NTPases, and downstream signaling cascades that govern cellular responses. We believe that efforts to elucidate these mechanisms will greatly expand understanding of organ homeostasis, tissue remodeling, and fibrosis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a predoctoral fellowship, F31AG39992, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and research grants from NIH.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.L. and P.A.I. prepared figures; D.L. and P.A.I. drafted manuscript; D.L. and P.A.I. edited and revised manuscript; D.L. and P.A.I. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev 58: 281–341, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed MS, Oie E, Vinge LE, Yndestad A, Oystein Andersen G, Andersson Y, Attramadal T, Attramadal H. Connective tissue growth factor–a novel mediator of angiotensin II-stimulated cardiac fibroblast activation in heart failure in rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol 36: 393–404, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarado-Castillo C, Harden TK, Boyer JL. Regulation of P2Y1 receptor-mediated signaling by the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase isozymes NTPDase1 and NTPDase2. Mol Pharmacol 67: 114–122, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson B, Dwyer K, Enjyoji K, Robson SC. Ecto-nucleotidases of the CD39/NTPDase family modulate platelet activation and thrombus formation: potential as therapeutic targets. Blood Cells Mol Dis 36: 217–222, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayata CK, Ganal SC, Hockenjos B, Willim K, Vieira RP, Grimm M, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM, Di Virgilio F, Pellegatti P, Diefenbach A, Idzko M, Hasselblatt P. Purinergic P2Y(2) receptors promote neutrophil infiltration and hepatocyte death in mice with acute liver injury. Gastroenterology 143: 1620–1629, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahammam M, Black SAJ, Sume SS, Assaggaf MA, Faibish M, Trackman PC. Requirement for active glycogen synthase kinase-3β in TGF-β1 upregulation of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) levels in human gingival fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305: C581–C590, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Barkauskas CE, Noble PW. Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Fibrosis. 7. New insights into the cellular mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 10.1152/ajpcell.00321.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batra N, Burra S, Siller-Jackson AJ, Gu S, Xia X, Weber GF, DeSimone D, Bonewald LF, Lafer EM, Sprague E, Schwartz MA, Jiang JX. Mechanical stress-activated integrin alpha5beta1 induces opening of connexin 43 hemichannels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 3359–3364, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baudino TA, Carver W, Giles W, Borg TK. Cardiac fibroblasts: friend or foe? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1015–H1026, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beigi R, Kobatake E, Aizawa M, Dubyak GR. Detection of local ATP release from activated platelets using cell surface-attached firefly luciferase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C267–C278, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beldi G, Enjyoji K, Wu Y, Miller L, Banz Y, Sun X, Robson SC. The role of purinergic signaling in the liver and in transplantation: effects of extracellular nucleotides on hepatic graft vascular injury, rejection and metabolism. Front Biosci 13: 2588–2603, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjaelde RG, Arnadottir SS, Overgaard MT, Leipziger J, Praetorius HA. Renal epithelial cells can release ATP by vesicular fusion. Front Physiol 4: 238, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blasche R, Ebeling G, Perike S, Weinhold K, Kasper M, Barth K. Activation of P2X7R and downstream effects in bleomycin treated lung epithelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44: 514–524, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonner F, Borg N, Jacoby C, Temme S, Ding Z, Flogel U, Schrader J. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase on immune cells protects from adverse cardiac remodeling. Circ Res 113: 301–312, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun OO, Lu D, Aroonsakool N, Insel PA. Uridine triphosphate (UTP) induces profibrotic responses in cardiac fibroblasts by activation of P2Y2 receptors. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 362–369, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner DA, Waterboer T, Choi SK, Lindquist JN, Stefanovic B, Burchardt E, Yamauchi M, Gillan A, Rippe RA. New aspects of hepatic fibrosis. J Hepatol 32: 32–38, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browne LE, Compan V, Bragg L, North RA. P2X7 receptor channels allow direct permeation of nanometer-sized dyes. J Neurosci 33: 3557–3566, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bujak M, Frangogiannis NG. The role of TGF-beta signaling in myocardial infarction and cardiac remodeling. Cardiovasc Res 74: 184–195, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnstock G. Discovery of purinergic signalling, the initial resistance and current explosion of interest. Br J Pharmacol 167: 238–255, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnstock G, Brouns I, Adriaensen D, Timmermans JP. Purinergic signaling in the airways. Pharmacol Rev 64: 834–868, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camelliti P, Borg TK, Kohl P. Structural and functional characterisation of cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 65: 40–51, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campanholle G, Ligresti G, Gharib SA, Duffield JS. Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Fibrosis. 3. Novel mechanisms of kidney fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C591–C603, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Adenosine in fibrosis. Mod Rheumatol 20: 114–122, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan ES, Montesinos MC, Fernandez P, Desai A, Delano DL, Yee H, Reiss AB, Pillinger MH, Chen JF, Schwarzschild MA, Friedman SL, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A(2A) receptors play a role in the pathogenesis of hepatic cirrhosis. Br J Pharmacol 148: 1144–1155, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Che J, Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptor occupancy stimulates collagen expression by hepatic stellate cells via pathways involving protein kinase A, Src, and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 signaling cascade or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol Pharmacol 72: 1626–1636, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JB, Liu WJ, Che H, Liu J, Sun HY, Li GR. Adenosine-5′-triphosphate up-regulates proliferation of human cardiac fibroblasts. Br J Pharmacol 166: 1140–1150, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science 314: 1792–1795, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiang DJ, Roychowdhury S, Bush K, McMullen MR, Pisano S, Niese K, Olman MA, Pritchard MT, Nagy LE. Adenosine 2A receptor antagonist prevented and reversed liver fibrosis in a mouse model of ethanol-exacerbated liver fibrosis. PLos One 8: e69114, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chunn JL, Molina JG, Mi T, Xia Y, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR. Adenosine-dependent pulmonary fibrosis in adenosine deaminase-deficient mice. J Immunol 175: 1937–1946, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clayton A, Al-Taei S, Webber J, Mason MD, Tabi Z. Cancer exosomes express CD39 and CD73, which suppress T cells through adenosine production. J Immunol 187: 676–683, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clemens MG, Forrester T. Appearance of ATP in the coronary sinus effluent from isolated working rat heart in response to hypoxia [proceedings]. J Physiol 295: 50P–51P, 1979 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleutjens JP, Creemers EE. Integration of concepts: cardiac extracellular matrix remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Card Fail 8: S344–S348, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corriden R, Chen Y, Inoue Y, Beldi G, Robson SC, Insel PA, Junger WG. Ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (E-NTPDase1/CD39) regulates neutrophil chemotaxis by hydrolyzing released ATP to adenosine. J Biol Chem 283: 28480–28486, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corriden R, Insel PA. Basal release of ATP: an autocrine-paracrine mechanism for cell regulation. Sci Signal 3: re1, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creemers EE, Pinto YM. Molecular mechanisms that control interstitial fibrosis in the pressure-overloaded heart. Cardiovasc Res 89: 265–272, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dewald O, Zymek P, Winkelmann K, Koerting A, Ren G, Abou-Khamis T, Michael LH, Rollins BJ, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ Res 96: 881–889, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobaczewski M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix as a modulator of the inflammatory and reparative response following myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 504–511, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolmatova E, Spagnol G, Boassa D, Baum JR, Keith K, Ambrosi C, Kontaridis MI, Sorgen PL, Sosinsky GE, Duffy HS. Cardiomyocyte ATP release through pannexin 1 aids in early fibroblast activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H1208–H1218, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dranoff JA, Kruglov EA, Abreu-Lanfranco O, Nguyen T, Arora G, Jain D. Prevention of liver fibrosis by the purinoceptor antagonist pyridoxal-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonate (PPADS). In Vivo 21: 957–965, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dranoff JA, Kruglov EA, Robson SC, Braun N, Zimmermann H, Sevigny J. The ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase NTPDase2/CD39L1 is expressed in a novel functional compartment within the liver. Hepatology 36: 1135–1144, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dranoff JA, Ogawa M, Kruglov EA, Gaca MD, Sevigny J, Robson SC, Wells RG. Expression of P2Y nucleotide receptors and ectonucleotidases in quiescent and activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G417–G424, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, Park D, Woodson RI, Ostankovich M, Sharma P, Lysiak JJ, Harden TK, Leitinger N, Ravichandran KS. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature 461: 282–286, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eltzschig HK, Sitkovsky MV, Robson SC. Purinergic signaling during inflammation. N Engl J Med 368: 1260, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan D, Takawale A, Lee J, Kassiri Z. Cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart disease. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 5: 15, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feranchak AP, Fitz JG, Roman RM. Volume-sensitive purinergic signaling in human hepatocytes. J Hepatol 33: 174–182, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez P, Perez-Aso M, Smith G, Wilder T, Trzaska S, Chiriboga L, Franks AJ, Robson SC, Cronstein BN, Chan ES. Extracellular generation of adenosine by the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 promotes dermal fibrosis. Am J Pathol 183: 1740–1746, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fredj S, Bescond J, Louault C, Delwail A, Lecron JC, Potreau D. Role of interleukin-6 in cardiomyocyte/cardiac fibroblast interactions during myocyte hypertrophy and fibroblast proliferation. J Cell Physiol 204: 428–436, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedman SL, Sheppard D, Duffield JS, Violette S. Therapy for fibrotic diseases: nearing the starting line. Sci Transl Med 5: 167sr1, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia GE, Truong LD, Chen JF, Johnson RJ, Feng L. Adenosine A(2A) receptor activation prevents progressive kidney fibrosis in a model of immune-associated chronic inflammation. Kidney Int 80: 378–388, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gatof D, Kilic G, Fitz JG. Vesicular exocytosis contributes to volume-sensitive ATP release in biliary cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 286: G538–G546, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerasimovskaya EV, Ahmad S, White CW, Jones PL, Carpenter TC, Stenmark KR. Extracellular ATP is an autocrine/paracrine regulator of hypoxia-induced adventitial fibroblast growth. Signaling through extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 and the Egr-1 transcription factor. J Biol Chem 277: 44638–44650, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerasimovskaya EV, Tucker DA, Weiser-Evans M, Wenzlau JM, Klemm DJ, Banks M, Stenmark KR. Extracellular ATP-induced proliferation of adventitial fibroblasts requires phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, mammalian target of rapamycin, and p70 S6 kinase signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 280: 1838–1848, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghosh AK, Vaughan DE. PAI-1 in tissue fibrosis. J Cell Physiol 227: 493–507, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goldsmith EC, Bradshaw AD, Spinale FG. Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Fibrosis. 2. Contributory pathways leading to myocardial fibrosis: moving beyond collagen expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C393–C402, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gomez-Hernandez JM, de Miguel M, Larrosa B, Gonzalez D, Barrio LC. Molecular basis of calcium regulation in connexin-32 hemichannels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 16030–16035, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goncalves RG, Gabrich L, Rosario AJ, Takiya CM, Ferreira ML, Chiarini LB, Persechini PM, Coutinho-Silva R, Leite MJ. The role of purinergic P2X7 receptors in the inflammation and fibrosis of unilateral ureteral obstruction in mice. Kidney Int 70: 1599–1606, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodenough DA, Goliger JA, Paul DL. Connexins, connexons, and intercellular communication. Annu Rev Biochem 65: 475–502, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grenz A, Zhang H, Hermes M, Eckle T, Klingel K, Huang DY, Muller CE, Robson SC, Osswald H, Eltzschig HK. Contribution of E-NTPDase1 (CD39) to renal protection from ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J 21: 2863–2873, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gribble FM, Loussouarn G, Tucker SJ, Zhao C, Nichols CG, Ashcroft FM. A novel method for measurement of submembrane ATP concentration. J Biol Chem 275: 30046–30049, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hale MD, Hayden JD, Grabsch HI. Tumour-microenvironment interactions: role of tumour stroma and proteins produced by cancer-associated fibroblasts in chemotherapy response. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 36: 95–112, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harada H, Chan CM, Loesch A, Unwin R, Burnstock G. Induction of proliferation and apoptotic cell death via P2Y and P2X receptors, respectively, in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int 57: 949–958, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hennigs JK, Seiz O, Spiro J, Berna MJ, Baumann HJ, Klose H, Pace A. Molecular basis of P2-receptor-mediated calcium signaling in activated pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas 40: 740–746, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herrera A, Herrera M, Alba-Castellon L, Silva J, Garcia V, Loubat-Casanovas J, Alvarez-Cienfuegos A, Garcia JM, Rodriguez R, Gil B, Citores MA, Larriba MA, Casal JI, de Herreros AG, Bonilla F, Pena C. Protumorigenic effects of Snail-expression fibroblasts on colon cancer cells. Int J Cancer 10.1002/ijc.28613 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hinz B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol 127: 526–537, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoffmann C, Ziegler N, Reiner S, Krasel C, Lohse MJ. Agonist-selective, receptor-specific interaction of human P2Y receptors with beta-arrestin-1 and -2. J Biol Chem 283: 30933–30941, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Homolya L, Watt WC, Lazarowski ER, Koller BH, Boucher RC. Nucleotide-regulated calcium signaling in lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells from normal and P2Y(2) receptor (−/−) mice. J Biol Chem 274: 26454–26460, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hrafnkelsdottir T, Erlinge D, Jern S. Extracellular nucleotides ATP and UTP induce a marked acute release of tissue-type plasminogen activator in vivo in man. Thromb Haemost 85: 875–881, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 110: 341–350, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Janssen LJ, Farkas L, Rahman T, Kolb MR. ATP stimulates Ca(2+)-waves and gene expression in cultured human pulmonary fibroblasts. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 2477–2484, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jhandier MN, Kruglov EA, Lavoie EG, Sevigny J, Dranoff JA. Portal fibroblasts regulate the proliferation of bile duct epithelia via expression of NTPDase2. J Biol Chem 280: 22986–22992, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jun JI, Lau LF. Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10: 945–963, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaczmarek-Hajek K, Lorinczi E, Hausmann R, Nicke A. Molecular and functional properties of P2X receptors–recent progress and persisting challenges. Purinergic Signal 8: 375–417, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaiser RA, Oxhorn BC, Andrews G, Buxton IL. Functional compartmentation of endothelial P2Y receptor signaling. Circ Res 91: 292–299, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kakkar R, Lee RT. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7: 827–840, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karmouty-Quintana H, Xia Y, Blackburn MR. Adenosine signaling during acute and chronic disease states. J Mol Med (Berl) 91: 173–181, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kauffenstein G, Drouin A, Thorin-Trescases N, Bachelard H, Robaye B, D'Orleans-Juste P, Marceau F, Thorin E, Sevigny J. NTPDase1 (CD39) controls nucleotide-dependent vasoconstriction in mouse. Cardiovasc Res 85: 204–213, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kauffenstein G, Furstenau CR, D'Orleans-Juste P, Sevigny J. The ecto-nucleotidase NTPDase1 differentially regulates P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptor-dependent vasorelaxation. Br J Pharmacol 159: 576–585, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kawate T, Michel JC, Birdsong WT, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of the ATP-gated P2X(4) ion channel in the closed state. Nature 460: 592–598, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Khakh BS, Burnstock G, Kennedy C, King BF, North RA, Seguela P, Voigt M, Humphrey PP. International union of pharmacology. XXIV. Current status of the nomenclature and properties of P2X receptors and their subunits. Pharmacol Rev 53: 107–118, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Köhler D, Eckle T, Faigle M, Grenz A, Mittelbronn M, Laucher S, Hart ML, Robson SC, Muller CE, Eltzschig HK. CD39/ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 provides myocardial protection during cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 116: 1784–1794, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koval M. Pathways and control of connexin oligomerization. Trends Cell Biol 16: 159–166, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kriz W, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in kidney fibrosis: fact or fantasy? J Clin Invest 121: 468–474, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kunapuli SP, Daniel JL. P2 receptor subtypes in the cardiovascular system. Biochem J 336: 513–523, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kunugi S, Iwabuchi S, Matsuyama D, Okajima T, Kawahara K. Negative-feedback regulation of ATP release: ATP release from cardiomyocytes is strictly regulated during ischemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 416: 409–415, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lazarowski ER. Vesicular and conductive mechanisms of nucleotide release. Purinergic Signal 8: 359–373, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC, Harden TK. Mechanisms of release of nucleotides and integration of their action as P2X- and P2Y-receptor activating molecules. Mol Pharmacol 64: 785–795, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leask A. TGFbeta, cardiac fibroblasts, and the fibrotic response. Cardiovasc Res 74: 207–212, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li L, Fan D, Wang C, Wang JY, Cui XB, Wu D, Zhou Y, Wu LL. Angiotensin II increases periostin expression via Ras/p38 MAPK/CREB and ERK1/2/TGF-beta1 pathways in cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 91: 80–89, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lieber RL, Ward SR. Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Fibrosis. 4. Structural and functional consequences of skeletal muscle fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305: C241–C252, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lohman AW, Billaud M, Isakson BE. Mechanisms of ATP release and signalling in the blood vessel wall. Cardiovasc Res 95: 269–280, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Longhi MS, Robson SC, Bernstein SH, Serra S, Deaglio S. Biological functions of ecto-enzymes in regulating extracellular adenosine levels in neoplastic and inflammatory disease states. J Mol Med (Berl) 91: 165–172, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lopez B, Gonzalez A, Hermida N, Valencia F, de Teresa E, Diez J. Role of lysyl oxidase in myocardial fibrosis: from basic science to clinical aspects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1–H9, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lota HK, Wells AU. The evolving pharmacotherapy of pulmonary fibrosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 14: 79–89, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lu D, Insel PA. Hydrolysis of extracellular ATP by ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (ENTPD) establishes the set point for fibrotic activity in cardiac fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 288: 19040–19049, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lu D, Soleymani S, Madakshire R, Insel PA. ATP released from cardiac fibroblasts via connexin hemichannels activates profibrotic P2Y2 receptors. FASEB J 26: 2580–2591, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mallat A, Lotersztajn S. Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Fibrosis. 5. Novel insights into liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305: C789–C799, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McCurdy S, Baicu CF, Heymans S, Bradshaw AD. Cardiac extracellular matrix remodeling: fibrillar collagens and Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC). J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 544–549, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mediavilla-Varela M, Luddy K, Noyes D, Khalil FK, Neuger AM, Soliman H, Antonia S. Antagonism of adenosine A2A receptor expressed by lung adenocarcinoma tumor cells and cancer associated fibroblasts inhibits their growth. Cancer Biol Ther 14. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Morris GE, Nelson CP, Everitt D, Brighton PJ, Standen NB, Challiss RA, Willets JM. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and arrestin2 regulate arterial smooth muscle P2Y-purinoceptor signalling. Cardiovasc Res 89: 193–203, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nakamura T, Iwanaga K, Murata T, Hori M, Ozaki H. ATP induces contraction mediated by the P2Y(2) receptor in rat intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts. Eur J Pharmacol 657: 152–158, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nishida M, Ogushi M, Suda R, Toyotaka M, Saiki S, Kitajima N, Nakaya M, Kim KM, Ide T, Sato Y, Inoue K, Kurose H. Heterologous down-regulation of angiotensin type 1 receptors by purinergic P2Y2 receptor stimulation through S-nitrosylation of NF-kappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 6662–6667, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nishida M, Sato Y, Uemura A, Narita Y, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Nakaya M, Ide T, Suzuki K, Inoue K, Nagao T, Kurose H. P2Y6 receptor-Galpha12/13 signalling in cardiomyocytes triggers pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. EMBO J 27: 3104–3115, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.North RA, Jarvis MF. P2X receptors as drug targets. Mol Pharmacol 83: 759–769, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oda T, Jung YO, Kim HS, Cai X, Lopez-Guisa JM, Ikeda Y, Eddy AA. PAI-1 deficiency attenuates the fibrogenic response to ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 60: 587–596, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Okada SF, Nicholas RA, Kreda SM, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Physiological regulation of ATP release at the apical surface of human airway epithelia. J Biol Chem 281: 22992–23002, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Okada SF, Ribeiro CM, Sesma JI, Seminario-Vidal L, Abdullah LH, van Heusden C, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Inflammation promotes airway epithelial ATP release via calcium-dependent vesicular pathways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 49: 814–820, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ostrom RS, Gregorian C, Insel PA. Cellular release of and response to ATP as key determinants of the set-point of signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem 275: 11735–11739, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Penuela S, Gehi R, Laird DW. The biochemistry and function of pannexin channels. Biochim Biophys Acta 1828: 15–22, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pfleger C, Ebeling G, Blasche R, Patton M, Patel HH, Kasper M, Barth K. Detection of caveolin-3/caveolin-1/P2X7R complexes in mice atrial cardiomyocytes in vivo and in vitro. Histochem Cell Biol 138: 231–241, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pochynyuk O, Rieg T, Bugaj V, Schroth J, Fridman A, Boss GR, Insel PA, Stockand JD, Vallon V. Dietary Na+ inhibits the open probability of the epithelial sodium channel in the kidney by enhancing apical P2Y2-receptor tone. FASEB J 24: 2056–2065, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Porter KE, Turner NA. Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther 123: 255–278, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rerolle JP, Hertig A, Nguyen G, Sraer JD, Rondeau EP. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 is a potential target in renal fibrogenesis. Kidney Int 58: 1841–1850, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rieg T, Bundey RA, Chen Y, Deschenes G, Junger W, Insel PA, Vallon V. Mice lacking P2Y2 receptors have salt-resistant hypertension and facilitated renal Na+ and water reabsorption. FASEB J 21: 3717–3726, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Riteau N, Gasse P, Fauconnier L, Gombault A, Couegnat M, Fick L, Kanellopoulos J, Quesniaux VF, Marchand-Adam S, Crestani B, Ryffel B, Couillin I. Extracellular ATP is a danger signal activating P2X7 receptor in lung inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182: 774–783, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Robson SC, Sevigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal 2: 409–430, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rosenkranz S. TGF-β1 and angiotensin networking in cardiac remodeling. Cardiovasc Res 63: 423–432, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ruiz-Ortega M, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Rodriguez-Vita J, Sanchez-Lopez E, Carvajal G, Egido J. Angiotensin II: a key factor in the inflammatory and fibrotic response in kidney diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 16–20, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Saez JC, Berthoud VM, Branes MC, Martinez AD, Beyer EC. Plasma membrane channels formed by connexins: their regulation and functions. Physiol Rev 83: 1359–1400, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Samuel CS, Unemori EN, Mookerjee I, Bathgate RA, Layfield SL, Mak J, Tregear GW, Du XJ. Relaxin modulates cardiac fibroblast proliferation, differentiation, and collagen production and reverses cardiac fibrosis in vivo. Endocrinology 145: 4125–4133, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schaff M, Receveur N, Bourdon C, Ohlmann P, Lanza F, Gachet C, Mangin PH. β-arrestin-1 participates in thrombosis and regulates integrin aIIbβ3 signalling without affecting P2Y receptors desensitisation and function. Thromb Haemost 107: 735–748, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schalper KA, Riquelme MA, Branes MC, Martinez AD, Vega JL, Berthoud VM, Bennett MV, Saez JC. Modulation of gap junction channels and hemichannels by growth factors. Mol Biosyst 8: 685–698, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Snead AN, Insel PA. Defining the cellular repertoire of GPCRs identifies a profibrotic role for the most highly expressed receptor, protease-activated receptor 1, in cardiac fibroblasts. FASEB J 26: 4540–4547, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Solini A, Iacobini C, Ricci C, Chiozzi P, Amadio L, Pricci F, Di Mario U, Di Virgilio F, Pugliese G. Purinergic modulation of mesangial extracellular matrix production: role in diabetic and other glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 67: 875–885, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Stenmark KR, Gerasimovskaya E, Nemenoff RA, Das M. Hypoxic activation of adventitial fibroblasts: role in vascular remodeling. Chest 122: 326S–334S, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Stenmark KR, Yeager ME, El Kasmi KC, Nozik-Grayck E, Gerasimovskaya EV, Li M, Riddle SR, Frid MG. The adventitia: essential regulator of vascular wall structure and function. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 23–47, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Su C, Bevan JA, Burnstock G. [3H]adenosine triphosphate: release during stimulation of enteric nerves. Science 173: 336–338, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Thimm J, Mechler A, Lin H, Rhee S, Lal R. Calcium-dependent open/closed conformations and interfacial energy maps of reconstituted hemichannels. J Biol Chem 280: 10646–10654, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Uehara K, Uehara A. P2Y1, P2Y6, and P2Y12 receptors in rat splenic sinus endothelial cells: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Histochem Cell Biol 136: 557–567, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Vaughn BP, Robson SC, Burnstock G. Pathological roles of purinergic signaling in the liver. J Hepatol 57: 916–920, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.von Kugelgen I. Pharmacological profiles of cloned mammalian P2Y-receptor subtypes. Pharmacol Ther 110: 415–432, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Vonend O, Oberhauser V, von Kugelgen I, Apel TW, Amann K, Ritz E, Rump LC. ATP release in human kidney cortex and its mitogenic effects in visceral glomerular epithelial cells. Kidney Int 61: 1617–1626, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang J, Haanes KA, Novak I. Purinergic regulation of CFTR and Ca2+-activated Cl− channels and K+ channels in human pancreatic duct epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C673–C684, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wihlborg AK, Balogh J, Wang L, Borna C, Dou Y, Joshi BV, Lazarowski E, Jacobson KA, Arner A, Erlinge D. Positive inotropic effects by uridine triphosphate (UTP) and uridine diphosphate (UDP) via P2Y2 and P2Y6 receptors on cardiomyocytes and release of UTP in man during myocardial infarction. Circ Res 98: 970–976, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Willis BC, Borok Z. TGF-β-induced EMT: mechanisms and implications for fibrotic lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L525–L534, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wilson PD, Hovater JS, Casey CC, Fortenberry JA, Schwiebert EM. ATP release mechanisms in primary cultures of epithelia derived from the cysts of polycystic kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 218–229, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wolff CI, Bundey RA, Insel PA. Involvement of P2Y receptors in TGFβ-induced EMT of MDCK cells (Abstract). FASEB J 22: 942.–5., 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wynn TA. Integrating mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med 208: 1339–1350, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xia Y, Dobaczewski M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Chen W, Biernacka A, Li N, Lee DW, Frangogiannis NG. Endogenous thrombospondin 1 protects the pressure-overloaded myocardium by modulating fibroblast phenotype and matrix metabolism. Hypertension 58: 902–911, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Xiao H, Shen HY, Liu W, Xiong RP, Li P, Meng G, Yang N, Chen X, Si LY, Zhou YG. Adenosine A2A receptor: a target for regulating renal interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. PLos One 8: e60173, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783: 673–694, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yokoyama U, Patel HH, Lai NC, Aroonsakool N, Roth DM, Insel PA. The cyclic AMP effector Epac integrates pro- and anti-fibrotic signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 6386–6391, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. The role of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in renal fibrosis. J Mol Med (Berl) 82: 175–181, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Fibrosis. 1. Common and organ-specific mechanisms associated with tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C216–C225, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhang J, Qi YF, Geng B, Pan CS, Zhao J, Chen L, Yang J, Chang JK, Tang CS. Effect of relaxin on myocardial ischemia injury induced by isoproterenol. Peptides 26: 1632–1639, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhou Y, Murthy JN, Zeng D, Belardinelli L, Blackburn MR. Alterations in adenosine metabolism and signaling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLos One 5: e9224, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhou Y, Schneider DJ, Blackburn MR. Adenosine signaling and the regulation of chronic lung disease. Pharmacol Ther 123: 105–116, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhou Y, Schneider DJ, Morschl E, Song L, Pedroza M, Karmouty-Quintana H, Le T, Sun CX, Blackburn MR. Distinct roles for the A2B adenosine receptor in acute and chronic stages of bleomycin-induced lung injury. J Immunol 186: 1097–1106, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Zhu J, Carver W. Effects of interleukin-33 on cardiac fibroblast gene expression and activity. Cytokine 58: 368–379, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Strater N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal 8: 437–502, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]