Abstract

Introduction

Monitoring and reduction of aversive tension is a core issue in dialectical behaviour therapy of patients. It has been shown that aversive tension is increased in adult borderline personality disorder and is linked to low emotion labelling ability. However, until now there is no documented evidence that patients with anorexia nervosa suffer from aversive tension as well. Furthermore the usability of a smartphone application for ambulatory monitoring purposes has not been sufficiently explored.

Methods and analysis

We compare the mean and maximum self-reported aversive tension in 20 female adolescents (12–19 years) with anorexia nervosa in outpatient treatment with 20 healthy controls. They are required to answer hourly, over a 2-day period, that is, about 30 times, four short questions on their smartphone, which ensures prompt documentation without any recall bias. At the close out, the participants give a structured usability feedback on the application and the procedure.

Ethics and dissemination

The achieved result of this trial has direct relevance for efficient therapy strategies and is a prerequisite for trials regarding dialectical behaviour therapy in anorexia nervosa. The results will be disseminated through peer-review publications. The ethics committee of the regional medical association in Mainz, Germany approved the study protocol under the reference number 837.177.13.

Trial Registration number

The trial is registered at the German clinical trials registration under the reference number DRKS00005228.

Keywords: Mental Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First controlled trial observing aversive tension in individuals with anorexia nervosa.

Momentary assessment for recognition bias reduction.

Using the personal smartphone devices of the participants for better compliance and fewer participation burden than in a trial using paper-based assessment methods.

Owing to the ambulatory monitoring design, only outpatients can participate.

The monitoring software was not primarily developed for ambulatory monitoring trials and therefore the usability could be improved.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a very severe disorder with the highest lethality in mental disorders.1 Owing to the often less than promising therapy outcomes,2 new ways to treat AN is still a developing research topic.3 4 Recently, an adaptation of the dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) for the treatment of eating disorders has been made,5 which was originally developed by Linehan6 7 for the treatment of chronically suicidal patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). DBT focuses mainly on emotion regulation problems as the core reason for BPD. In line with this model, commitment to changing dysfunctional behaviour, direct contact to therapists in acute crisis (for example, telephone coaching). and understanding of aversive tension as a consequence of missing emotion regulation strategies are therefore important parts of DBT. As DBT is currently discussed as a possible treatment solution for AN,5 empirical research on the importance of its core assumptions (inter alia emotion dysregulation, aversive tension) in AN is clearly needed.

In regard to BPD, states of aversive tension have been reported previously.8–11 Although in literature those states have been described using many different terms such as ‘psychological distress’,10 ‘heightened emotional arousal’,12 ‘tension’13 or ‘aversive tension’,9 14 we will use the term ‘aversive tension’ for clarity reasons. Aversive tension refers to an emotional state that is perceived as negative and normally attended by high arousal,15 but is not linked to a specific emotion. Hence the experience of aversive tension urges the subject to terminate this state immediately. Patients with BPD often use non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) as a maladaptive strategy to reduce aversive tension16 17 and to feel rapid relief from corresponding negative emotions.18

There are studies examining actual perceived aversive tension of patients with BPD.8–10 Using ambulatory monitoring methods in two of their studies, both research groups could show that patients with BPD differ in the experience of aversive tension from healthy controls regarding mean levels and variation over time (higher levels, more frequent and rapid increases, longer persistence and slower refraction of aversive tension). Stiglmayr et al9 could also examine that applied DBT skills led to a reduction of aversive tension. Moreover, states of high-aversive tension seem to be linked to an inability to label emotions at the same time, but only for patients with BPD.10 14 Even the previous value of aversive tension seems to be in some way related to emotion identification difficulties 1 h later,14 which suggests that aversive tension impairs the ability to name experienced emotions immediately and for a certain time span.

The previous mentioned findings are in line with the transactional model of BPD proposed by Fruzzetti et al19 understanding BPD as a disorder of emotion regulation. Clear and brief, biological vulnerability together with invalidating responses from others regarding the emotional state of the subject will lead to aversive tension. To reduce these states of aversive tension, patients with BPD will then most likely use dysfunctional emotion regulation strategies like NSSI. Recently Haynos and Fruzetti12 adapted this model for AN, emphasising the idea that AN is also a disorder of emotion regulation. They suggest that a person with AN will experience aversive tension especially after events related to food intake or body exposure. Instead of using NSSI as an emotion regulation strategy like patients with BPD, persons suffering from AN will tend to excessively exercise (after food intake) or display starvation behaviour (after eg, body exposure, criticism by intimates) for a brief reduction in arousal. This will thereby lead, via negative reinforcement, to a circulus vitiosus with more frequent starvation behaviour and body weight reduction. This is supported by a recent study relating lower body mass indices (BMIs) in women with acute AN to fewer emotion regulation problems, although this association was not observed in other subsamples.20

Although clinical practice indicates that patients with AN benefit from DBT skills training, empirical research is still scarce. So far, there has been only one controlled trial conducted comparing DBT with treatment as usual in adolescent patients with AN.21 Few pilot studies on adapted DBT programmes for patients with AN and a comorbid BPD exist,22 23 but all of these findings are promising regarding the effectiveness of DBT in the therapy of AN. As previously mentioned, DBT focuses on emotion regulation. The previous studies regarding DBT treatment of AN suppose by adopting DBT for AN that emotion regulation problems and aversive tension are the main factors for starvation behaviour, but surprisingly the occurrence of aversive tension in AN was never questioned in an empirical study before. Neither is there any literature on the experience of aversive tension of adolescents, although DBT manuals for the treatment of adolescents with high risk for NSSI have been published recently.24 25 Regarding the inability to label emotions, it is also unclear if this is a specific BPD problem, a general psychopathology phenomenon or a consequence of aversive tension. Therefore, the main aim of this study is to show if adolescent patients with AN differ from control subjects in their report of experienced aversive tension. Additionally, we will investigate a possible relation to the ability to label emotions on an exploratory level.

In the past the observance of mood or behaviour in everyday life was mostly conducted by filling in paper-based diaries or more recently by using hand-held computers distributed by the research group.26 Owing to the lack of high quality and reasonably priced software, usually the programming for the hand-held computer devices was performed by the researcher himself. Currently, the wide distribution of smartphone devices especially in the population of adolescents offers a new way for an ambulatory monitoring of mood changes in daily course. For the most common smartphone software, Android and iOS, there are low priced and user-friendly monitoring software solutions available.27 The benefit of using the participants’ own devices may not only be the lower research costs. Especially in the research with adolescent participants, a software application run on their smartphone instead of a less accessible and old fashioned research device could be preferred and lead to less missing data.

Aims

The aim of this study is to investigate for the first time the experience of aversive tension of patients with an AN diagnosis. We hypothesise that in a period of 2 days the patient subsample will report (1) higher average values and (2) higher maximum values of aversive tension.

Methods and analysis

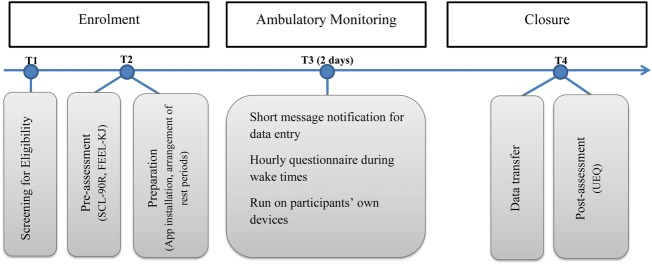

The current study will be an observational case–control study with a sample size of at least 40 participants. Figure 1 provides a brief overview of the assessment schedule.

Figure 1.

Study schedule.

Participants and recruitment

The study is taking place at the medical centre Rheinhessen-Fachklinik Mainz in cooperation with the Department for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. The entity will invite outpatients with AN to participate in the study. Control participants are recruited in the local region by word-of-mouth invitation of the study coordinator.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Owing to the low prevalence of AN in the male population28 and to avoid confounding variables by gender, only female outpatients between 12 and 19 years with a current diagnosis of AN (according to the International Classification of Diseases, V.10; ICD-10) will be included. The diagnosis must be made by the outpatient clinic of the medical centre Rheinhessen-Fachklinik Mainz with the German version of the Eating Disorder Examination adapted for children (chEDE),29 a structured interview for the assessment of eating disorders. Comorbidity will be assessed with the German Kiddie-Sads-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL), a reliable and valid semistructured interview for the assessment of mental disorders.30 Participants of the patient group will be excluded in case of or presumed diagnosis of a personality disorder. In case of a BMI under the third centile, patients will be referred to inpatient treatment and will not be included in the study. Other comorbid disorders will be allowed if AN is the primary diagnosis. Control participants with any diagnosis of a mental disorder in the past 5 years will be excluded, as well as control participants with a high symptom burden based on the global severity index. For a summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria, see table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Patient group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | ||

| Gender | Female | Female |

| Age | 12–19 years | 12–19 years |

| Disorder | Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (F50.0), based on the chEDE | Healthy controls |

| Experience with smartphones | Existent | Existent |

| Exclusion criteria | ||

| Disorder | (presumed) diagnosis of a personality disorder BMI <3rd BMI centile |

Any diagnosis of a mental disorder in the past 5 years High symptom burden (T≥63 on the global severity index of the SCL90-R) |

BMI, body mass index;chEDE, eating disorder examination adapted for children; SCL90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-R.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome of the study is the mean value of aversive tension; coprimary is the maximum value of aversive tension.

Main secondary outcome is the daily course of aversive tension (eg, increases, decreases), the ability to label emotions and reported emotions and occupations. To assess the acceptance of the method, we will report differences in the compliance of both groups.

In addition we will explore the usability of the smartphone application and the acceptance of using a personal smartphone. Influencing factors are sociodemographic data, mental symptom burden, emotion regulation strategies (FEEL-KJ) and the actual experienced emotion as well as the actual occupation at each assessment moment.

Assessments

Both control participants and patients will participate in a prequestionnaire (sociodemographics, SCL90-R, FEEL-KJ) before the actual ambulatory monitoring and a postquestionnaire (adapted version of the UEQ) afterwards, measuring the user experience of the applied software. In addition to a short sociodemographic questionnaire, participants will fill in an electronic version of the following questionnaires:

Symptom Checklist-90-R

The symptom checklist (German version) is a measure of general psychopathological symptom severity and has been widely used in studies and clinical practice.31 Besides three global indices, the SCL90-R measures the intensity of specific symptom groups on nine subscales. The internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) for the scales are in the range of and α=0.97 and the test has shown a test–retest reliability of r≥0.69 In a large German adolescent survey, the SCL90-R showed a high general validity for the use as an instrument for measuring general symptom burden.32 The manual of the SCL90-R proposes a cut-off at T≥63 at the global severity index for participants with a high symptom burden.

FEEL-KJ

The FEEL-KJ is a German instrument for the measurement of emotion regulation of children and adolescents.33 It measures multidimensional and emotion-specific emotion regulation strategies for the emotions anxiety, anger and grief providing both adaptive (eg, cognitive problem solving, acceptance) and maladaptive strategies (eg, perseverance, resignation). Internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) for the two secondary strategies are good (α=0.82 for maladaptive, α=0.93 for adaptive strategies). Six week test–retest reliabilities for all strategies are between r=0.62 and r=0.81. Regarding construct validity, adaptive emotion regulation strategies show generally low correlations with maladaptive strategies which indicate independent secondary strategies. Factorial analysis supports the two component structure. Correlations with other scales show sufficient construct validity of the questionnaire.

User experience questionnaire

The user experience questionnaire (UEQ) is a questionnaire primarily developed for measuring the usability of websites34 and one of the few reliable scales for measuring usability. This is conducted by rating the website or application on various dimensions on a seven-point scale (eg, if an application is rather attractive than unattractive, more creative than dull).

The UEQ contains six subscales of different facets of user experience. Internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) for the German version of the subscales are between α=0.73 and α=0.89. Participants will fill in the UEQ after the ambulatory monitoring when they meet again with the study coordinator at the medical centre to copy the data from their smartphones. Owing to technical reasons, this questionnaire will be provided as a paper version.

Ambulatory monitoring

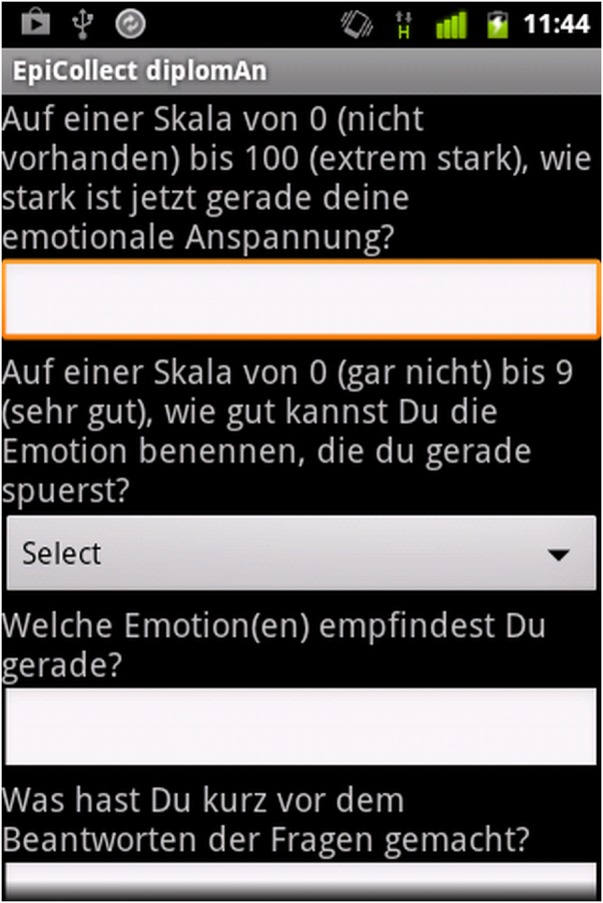

Both groups will participate in an ambulatory monitoring for 2 days assessing data on their own smartphones after they have filled in a prequestionnaire. The free data collecting software Epicollect35 developed at the Imperial College London will be used on the participants’ own devices. A screenshot of the application can be seen in figure 2. After informing the participants about how to use the application, researchers will download the software and the questionnaire form on the smartphone and arrange the individual sleeping periods with the participants when they will not be asked for data entry. Additionally, the participants will receive a short briefing regarding aversive tension. The participants will be advised that aversive tension is a state of unpleasant and high arousal which is only randomly accompanied by a specific emotion in line with the DBT manuals.7 25 They will be told that on a scale from 0 to 100, the range of 70–100 stands for high tension normally only experienced in traumatic situations. Furthermore, participants will be told to imagine two exemplary events and their respective range of aversive tension that could possibly be provoked by such events. Data will be assessed during school days only, to prevent confounding the data by participants who participate on weekends. Earlier studies9 suggest that a 2-day monitoring provides sufficient data for analysis without the risk of loss of interest. During the 48 h of the monitoring, participants will receive hourly text messages to their mobile phones which prompt to fill in the questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of four items which can be seen in table 2.

Figure 2.

Ambulatory monitoring questionnaire as seen in the smartphone application.

Table 2.

Items, answer categories and outcome variables of the ambulatory monitoring questionnaire

| Item (original German version) | Answer category | Outcome variable |

|---|---|---|

| On a scale from 0—not present to 100—extremely intense, at this time, how intense is your emotional tension? (Auf einer Skala von 0 [nicht vorhanden] bis 100 [extrem stark], wie stark ist jetzt gerade deine emotionale Anspannung?) | 0–100, answered by filling in the number in a text field | Aversive tension |

| On a scale from 0—not at all to 9—very good, how well can you name the emotion that you are feeling right now? (Auf einer Skala von 0 [gar nicht] bis 9 [sehr gut], wie gut kannst Du die Emotion benennen, die Du gerade spürst?) | 0–9, answered by single choice in a drop down selection menu | Ability to label emotions |

| Which emotion(s) are you experiencing right now? (Welche Emotion[en] verspürst du gerade?) | Open text field | Emotions |

| What have you done immediately before responding to the questions? (Was hast du kurz vor dem Beantworten der Fragen gemacht?) | Open text field | Occupation |

Sample size calculation

In this study, aversive emotional tension is scored between 0 and 100. An earlier study9 compared the experienced aversive tension of patients with BPD with mentally healthy control participants finding that the adult control participants reported mean values of tension near 0 on a scale from 0 to 9. In another study, Ebner-Priemer et al10 used a scale from 0 to 10 to measure aversive tension. Different from them, we will use a broader scale (0 to 100) as used in DBT manuals.7 25 Furthermore, we will examine adolescent participants who might experience more aversive tension than adults. Therefore, we expect slightly increased mean levels and variances of aversive tension compared to the former mentioned study both in patient and control group. We expect an effect size of d≥0.8 to be a clinically relevant.36 As to the best knowledge of the investigators, there is no literature on the experience of aversive tension either of individuals with a history of AN or of adolescents. Hence, based on previous findings regarding adults and BPD,9 we suppose mean levels of 60 (patient group; SDpatients=20) and 40 (control group, SDcontrols=15) regarding aversive tension. To achieve a statistical power of 80% of a two-sided t test, a group sample size of at least 16 participants (with α=0.05/2 for testing two separate hypotheses, two-sided test) will be necessary. Furthermore, we will calculate with an overhead of 25% and therefore include at least 20 participants in each group.

Statistical analyses

Data will be assessed using SPSS software (V.21; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Correctness of the paper-submitted data will be assured by double entry of the data. All three hypotheses will be tested separately. To ensure a global α error of α=0.05 we will adjust with the Holm37 procedure by organising hypotheses regarding their obtained p values.

To test for group differences in aversive tension (1), we will first conduct mean values of aversive tension for every participant. Group means of patient and control group will then be tested using Welch's t test for unequal variances. For hypothesis (2), we will test for differences in the reported individual maximum values using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

On an exploratory level we will analyse the time course of aversive tension, its relation to the ability to label emotions and possible group differences regarding the valence of named emotions. We will then analyse differences regarding the compliance (missing values). Furthermore, we will group the named emotions in positive and negative to compute an index of valence. Regarding the usability of the method, we will analyse the reported usability of the software.

Dissemination

The study will be conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Data protection protocol was approved by the commissioner for data protection of the Rheinhessen-Fachklinik Mainz, Germany. Participation will require informed consent by participants and legal guardians in case of minority. Participants and legal guardians can withdraw from the study at any time without further explanation and any negative consequences.

Results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and presentations at conferences.

Discussion

In this protocol we have presented the first controlled trial for studying aversive tension in patients with AN in an ambulatory monitoring setting. Thereby, the experience of aversive tension in patients with AN and adolescent control participants will be observed hourly in a 48 h monitoring using the participants’ own devices. We hope that our study will provide data for a better understanding of how aversive tension and emotion regulation are part of this specific eating disorder. In contrast to paper-based documentation, the presented concept is an advantage due to reduced reminding efforts and recall bias. The achieved result of this trial will furthermore have direct relevance for DBT and will be a basis for further research regarding efficiency and therapy outcomes of DBT for AN.

Owing to the ambulatory monitoring design, there are some limitations of the study such as observance of outpatients only, as inpatients might experience stronger states of aversive tension. Conversely, comparing outpatients and control participants allows us to collect data in a daily life setting including school times.

A possible trigger for aversive tension in patients with AN might be meal situations. We decided not to assess the last food intake, as this might cause aversive tension itself and therefore confound the data. Additionally, there is no literature on which situations or emotions could trigger aversive tension in patients with AN. Therefore, we decided to conduct a naturalistic trial.

An additional challenge is the technical aspect of the ambulatory monitoring. As the software was not designed for ambulatory monitoring purposes in particular, the handling is somewhat more complex than a simple paper-based diary or an expensive commercial software solution. However, we expect that the possible benefits, such as more privacy during filling in the items, of the software will outweigh any possible drawbacks. If the usability outcomes are positive, this might encourage other researchers to use this free available application or to further develop it, therefore making it more suitable for ambulatory monitoring purposes, for example, by implementing a notification function. The principle of using the smartphone as a tool in therapy for promptly self-reflection has to be developed in further investigations. A transfer of the concept to further conditions and disorders is welcomed.

Regarding the statistical analysis, group comparisons of aggregated measures only permit analysis on one data level.38 As in this study, we are primarily interested in a general group difference and not on interactions with other variables, standard group comparisons are the most economic statistical analysis regarding sample size and data structure requirements. However, if group differences appear to be significant, subsequent analyses using more advanced techniques, for example, graphical vector analysis39 or mixed model approaches38 are recommended.

After this trial has been successfully conducted and if a difference in the experience of aversive tension of patients with AN compared to control participants has been observed, the relevance of aversive tension in other eating disorders could be examined and effects of DBT for patients with AN or adolescent patients in general on aversive tension could be investigated more thoroughly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dr Eva Möhler and Andrea Dixius of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the SHG Klinik Idar-Oberstein for their participation in the development of this study. Patricia Meinhardt conducted proof reading. The authors are also thankful to all participants.

Footnotes

Contributors: DRK carried out the acquisition of data, participated in the design of the study and coordination and drafted the manuscript. AB and FH conceived the study, participated in its design and revised the manuscript. EJ participated in the design of the study and coordination and involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors are employees of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy Mainz (Michael Huss), a collaboration unit between University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz and Rheinhessen Fachklinik Mainz.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the regional medical association in Mainz, Germany under the reference number 837.177.13.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zipfel S, Löwe B, Reas DL, et al. Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: lessons from a 21-year follow-up study. Lancet 2000;355:721–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:293–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zipfel S, Wild B, Groß G, et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:127–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt U, Renwick B, Lose A, et al. The MOSAIC study—comparison of the Maudsley Model of Treatment for Adults with Anorexia Nervosa (MANTRA) with Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM) in outpatients with anorexia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified, anorexia nervosa type: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sipos V, Bohus M, Schweiger U. Dialektisch-behaviorale Therapie für Essstörungen (DBT-E). Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2011;61:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press, 1993a [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linehan MM. Skill training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press, 1993b [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stiglmayr CE, Shapiro DA, Stieglitz RD, et al. Experience of aversive tension and dissociation in female patients with borderline personality disorder—a controlled study. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35:111–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stiglmayr CE, Grathwol T, Linehan MM, et al. Aversive tension in patients with borderline personality disorder: a computer-based controlled field study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:372–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Schlotz W, et al. Distress and affective dysregulation in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2008;196:314–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, DeLuca CJ, et al. The pain of being borderline: dysphoric states specific to borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1998;6:201–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynos AF, Fruzetti AE. Anorexia nervosa as a disorder of emotion dysregulation: evidence and treatment implications. Clin Psychol 2011;18:183–202 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coid J. An affective syndrome in psychopaths with borderline personality-disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1993;162:641–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff S, Stiglmayr C, Bretz HJ, et al. Emotion identification and tension in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Br J Clin Psychol 2007;46:347–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980;39:1161–78 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2002;111:198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reitz S, Krause-Utz A, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, et al. Stress regulation and incision in borderline personality disorder—a pilot study modeling cutting behavior. J Pers Disord 2012;26:605–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:371–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fruzzetti AE, Shenk C, Hoffman PD. Family interaction and the development of borderline personality disorder: a transactional model. Dev Psychopathol 2005;17:1007–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brockmeyer T, Grosse Holtforth M, Bents H, et al. Starvation and emotion regulation in anorexia nervosa. Compr Psychiatr 2012;53:496–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salbach-Andrae H, Bohnekamp I, Bierbaum T, et al. Dialektisch Behaviorale Therapie (DBT) und Kognitiv Behaviorale Therapie (CBT) für Jugendliche mit Anorexia und Bulimia nervosa im Vergleich. Kindheit und Entwicklung 2009;18:180–90 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kröger C, Schweiger U, Sipos V, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy and an added cognitive behavioural treatment module for eating disorders in women with borderline personality disorder and anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa who failed to respond to previous treatments. An open trial with a 15-month follow-up. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2010;41:381–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Federici A, Wisniewski L. An intensive DBT program for patients with multidiagnostic eating disorder presentations: a case series analysis. Int J Eat Disord 2013;46:322–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan M. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. New York: Guilford Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleischhaker C, Sixt B, Schulz E. DBT-A: Dialektisch-behaviorale Therapie für Jugendliche. Berlin: Springer, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fahrenberg J, Myrtek M, Pawlik K, et al. Ambulatory assessment—monitoring behavior in daily life settings. Eur J Psychol Assess 2007;23:206–13 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubiak T, Krog K. Computerized sampling of experience and behavior. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, eds. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York: Guilford, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjelsås E, Bjørnstrøm C, Götestam KG. Prevalence of eating disorders in female and male adolescents (14–15 years). Eat Behav 2004;5:13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilbert A, Buerger A, Hartmann AS, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination adapted for children. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2013;21:330–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delmo C, Weiffenbach O, Gabriel M, et al. Kiddie-SADS—present and lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Deutsche Forschungsversion. Frankfurt: University of Frankfurt/M, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franke GH. SCL-90-R. Die Symptom-Checkliste von Derogatis—Deutsche Version. Göttingen: Beltz Test, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Essau CA, Groen G, Conradt J, et al. Validität und Reliabilität der SCL-90-R: Ergebnisse der Bremer Jugendstudie. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie 2001;22: 139–52 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grob A, Smolenski C. Fragebogen zur Erhebung der Emotionsregulation bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (FEEL-KJ). Bern: Verlag Hans Huber, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laugwitz B, Held T, Schrepp M. Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In: Holzinger A, ed. HCI and usability for education and work. Berlin: Springer, 2008:63–76 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aanensen DM, Huntley DM, Feil EJ, et al. EpiCollect: linking smartphones to web applications for epidemiology, ecology and community data collection. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian journal of statistics. Scand Stat Theory Appl 1979;6:65–70 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nezlek JB, Schröder-Abé M, Schütz A. Mehrebenenanalysen in der psychologischen Forschung. Psychologische Rundschau 2006;4:213–23 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wild B, Eichler M, Friedrich HC, et al. A graphical vector autoregressive modeling approach to the analysis of electronic diary data. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.