ABSTRACT

The type VII secretion systems are conserved across mycobacterial species and in many Gram-positive bacteria. While the well-characterized Esx-1 pathway is required for the virulence of pathogenic mycobacteria and conjugation in the model organism Mycobacterium smegmatis, Esx-3 contributes to mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition in these bacteria. Here we show that several Esx-3 components are individually required for function under low-iron conditions but that at least one, the membrane-bound protease MycP3 of M. smegmatis, is partially expendable. All of the esx-3 mutants tested, including the ΔmycP3ms mutant, failed to export the native Esx-3 substrates EsxHms and EsxGms to quantifiable levels, as determined by targeted mass spectrometry. Although we were able to restore low-iron growth to the esx-3 mutants by genetic complementation, we found a wide range of complementation levels for protein export. Indeed, minute quantities of extracellular EsxHms and EsxGms were sufficient for iron acquisition under our experimental conditions. The apparent separation of Esx-3 function in iron acquisition from robust EsxGms and EsxHms secretion in the ΔmycP3ms mutant and in some of the complemented esx-3 mutants compels reexamination of the structure-function relationships for type VII secretion systems.

IMPORTANCE

Mycobacteria have several paralogous type VII secretion systems, Esx-1 through Esx-5. Whereas Esx-1 is required for pathogenic mycobacteria to grow within an infected host, Esx-3 is essential for growth in vitro. We and others have shown that Esx-3 is required for siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. In this work, we identify individual Esx-3 components that contribute to this process. As in the Esx-1 system, most mutations that abolish Esx-3 protein export also disrupt its function. Unexpectedly, however, ultrasensitive quantitation of Esx-3 secretion by multiple-reaction-monitoring mass spectrometry (MRM-MS) revealed that very low levels of export were sufficient for iron acquisition under similar conditions. Although protein export clearly contributes to type VII function, the relationship is not absolute.

INTRODUCTION

One of the many strategies evolved by Mycobacterium tuberculosis to prevent clearance by the host is protein export via Esx-1 (1–3), a specialized secretion system that is also required for conjugation in M. smegmatis (4, 5). There are four paralogous esx loci in the M. tuberculosis genome (6–8), but the functions of these Esx systems are just beginning to be revealed (9–19, 55).

Whereas Esx-1 is essential for the in vivo growth of pathogenic mycobacteria, there is strong evidence that Esx-3 is essential for in vitro growth (12, 13, 19, 20). Building on observations that esx-3 expression responds to iron and zinc availability (21, 22), we and others have demonstrated that Esx-3 is required for mycobacterial growth in low iron (12, 13, 19). Mycobacteria acquire iron by at least two siderophore pathways—exochelin, present in fast-growing species, such as M. smegmatis, and mycobactin, present in nearly all species (23–25)—in addition to a porin-based, low-affinity iron transport system (26) and the heme uptake system (27, 28). Epistasis experiments using M. smegmatis strains with deficiencies in Esx-3 and in the production of exochelin or mycobactin show that Esx-3 functions in iron acquisition via the mycobactin pathway (13). Moreover, addition of purified, iron-bound mycobactin does not rescue the low-iron growth defect, suggesting that Esx-3 is required for optimal utilization of the siderophores (13).

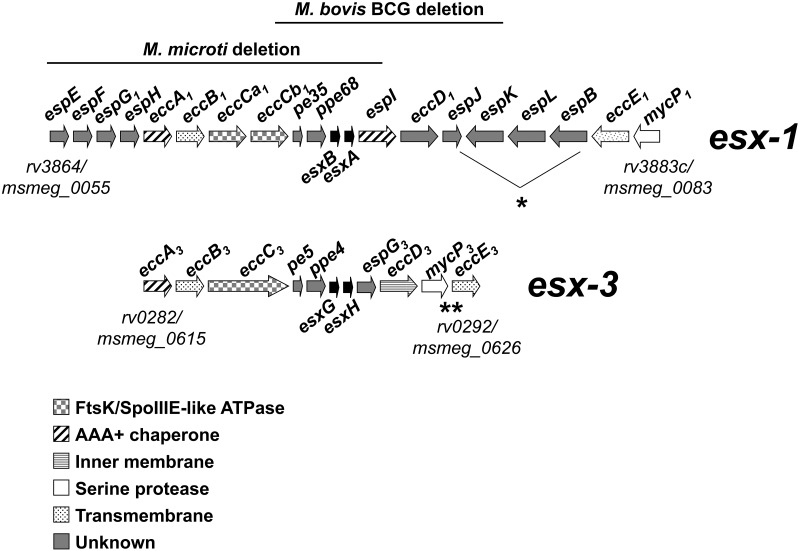

The organizations and contents of the esx-1 and esx-3 loci are similar (8). Both encode small, secreted proteins; Esx-1 contains EsxB (Cfp-10) and EsxA (Esat-6), and Esx-3 contains the paralogous EsxG and EsxH proteins (Fig. 1). We use the systematic nomenclature proposed by Bitter et al. (29). Genes that flank esxB/A and esxG/H include those encoding EccC3 (a putative FtsK/SpoIIIE ATPase that is paralogous to EccCa1/EccCb1 [where the “a” and “b” suffixes indicate the parts of the split gene and the subscript number refers to the esx-1 gene cluster]), EspG3 (a putative soluble protein of unknown function that is paralogous to EspG1), EccD3 (paralogous to the hypothesized secretion channel protein EccD1), and MycP3 (paralogous to the membrane-bound protease MycP1) (8).

FIG 1 .

Schematic diagram of gene conservation in mycobacterial esx-1 and esx-3 loci. ∗, the M. smegmatis esx-1 locus has a slightly different organization than the M. tuberculosis region from espJ to espB (5, 8); ∗∗, there is no MSMEG_0625, mycP3ms is MSMEG_0624, and eccE3ms is MSMEG_0626. We use the nomenclature proposed by Bitter et al. (29). Briefly, the terms ecc and esp, respectively, stand for esx conserved component and Esx-1 secretion-associated protein. The alphabetic suffix of conserved esx genes follows the gene order in the esx-1 locus. The numerical subscript at the end of the gene name refers to the esx cluster to which the gene belongs. We also provide the standard M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis gene numbers at the beginning and end of each locus for comparison. Although not listed in the NCBI or SmegmaList databases, MSMEG_0620 is esxGms and MSMEG_0621 is esxHms.

Multiple studies on the Esx-1 system support a model in which the FtsK/SpoIIIE ATPase EccCa1/EccCb1 provides energy to propel EsxB and EsxA across the cytoplasmic membrane via a translocation pore composed of EccD1 (30–32). It is not yet clear how type VII substrate proteins cross the cell envelope. Esx-1 may simply export these proteins across the cell envelope into the extracellular space. Alternatively, it may act only across the cytoplasmic membrane and require a mechanism for driving substrates across the remainder of the thick mycobacterial cell wall. Such a structure may be composed of yet-unidentified components or of EsxA, EsxB, and possibly other unlinked Esx-1 substrates (33, 34).

EspG1, EccCa1/EccCb1, EccD1, and MycP1 are required for both EsxB and EsxA export and Esx-1 function in most mycobacterial species tested (3, 5, 35–41), prompting early speculation that EsxB and EsxA are the effector proteins of the secretion system. However, there have since been reports of several Esx-1 mutations that abolish function without affecting EsxB and EsxA export (4, 35, 42, 43), as well as two genetic perturbations that prevent M. tuberculosis EsxB (EsxBmt) and EsxAmt secretion but do not alter M. tuberculosis virulence (44). These studies suggest that the relationship between protein export and Esx function may be more complicated than previously assumed.

Esx-3 exports EsxH (13) and, as we show here, EsxG. We found that several M. smegmatis Esx-3 components were individually required for export of EsxHms and EsxGms and for iron acquisition. However, we also observed low or even no detectable secretion for some strains that were able to grow to wild-type levels in low iron. The apparent separation of the phenotypes suggests new models for the associations between Esx structure and function.

RESULTS

Esx-3 components are required for low-iron growth.

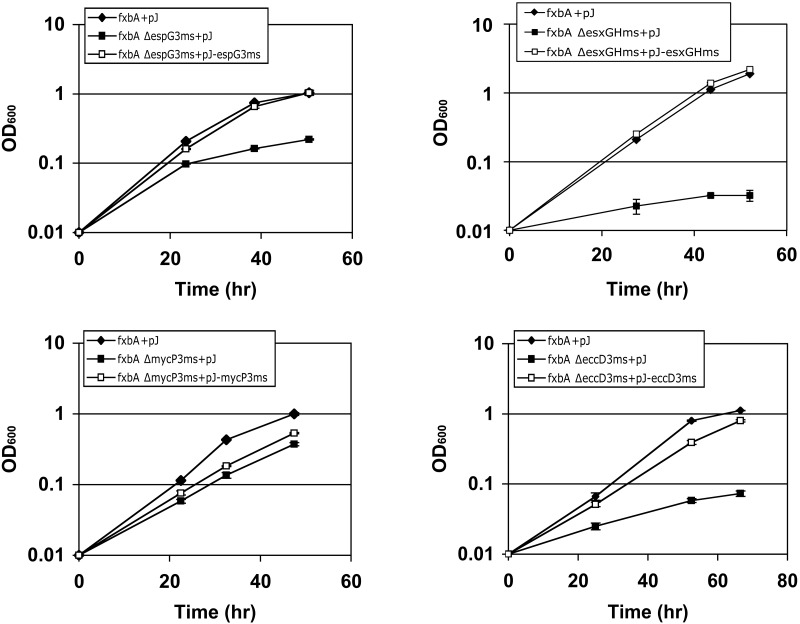

We have previously shown that Esx-3 is required for mycobacterial growth in low-iron medium via the mycobactin pathway (13). The secretion system is essential for growth in M. tuberculosis (12, 13, 20), however, complicating efforts to test the contributions of individual Esx-3 components to the function of the entire system. The model organism M. smegmatis can grow without functional Esx-3 in normal growth medium. We therefore constructed unmarked, in-frame deletions of esx-3 genes in M. smegmatis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Because M. smegmatis has partially redundant siderophore-based iron acquisition mechanisms, i.e., the mycobactin and exochelin pathways (24), we combined each esx-3 deletion with an insertional mutation in fxbA, which encodes a formyl transferase required for exochelin synthesis. Previously, we found that the fxbA ΔeccC3ms mutant grows significantly more slowly than the fxbA strain in low-iron medium (13). Although the fxbA ΔesxGHms, fxbA ΔespG3ms, and fxbA ΔeccD3ms mutants display similar low-iron growth deficiencies, the fxbA ΔmycP3ms strain has a less pronounced defect (Fig. 2 and 3). These strains are rescued by the presence of iron (Fig. S2) and upon reintroduction of the corresponding esx-3 gene (13) (Fig. 2). Thus, M. smegmatis growth in low iron requires the Esx-3 components EccC3ms, EsxGms/EsxHms, EspG3ms, and EccD3ms, with a more minor contribution from MycP3ms.

FIG 2 .

Esx-3 components contribute to low-iron growth. The growth of the fxbA and fxbA esx-3 M. smegmatis mutants in low-iron medium was monitored by determining their optical densities at 600 nm. pJ, pJEB402 vector; pJ-[gene name], pJEB402 containing the indicated M. smegmatis gene. The experiments were performed 2 to 6 times in triplicate. Representative data are shown, and error bars represent the standard deviations from the replicates.

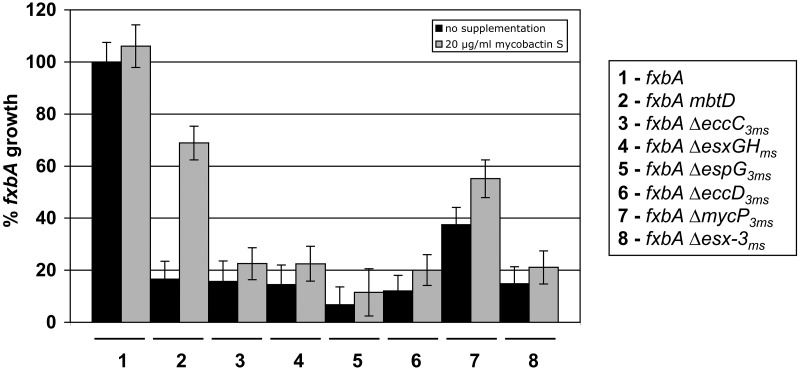

FIG 3 .

Loss of Esx-3 components is not rescued by exogenous mycobactin. Growth of fxbA, fxbA mbtD, and fxbA esx-3 mutants in unsupplemented, low-iron medium or in low-iron medium containing 20 µg/ml mycobactin S at 48 h. The experiment was performed at least three times in triplicate. Representative data are shown and are expressed as percentages of the fxbA mutant’s growth in low-iron medium. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the proportions.

Esx-3 components contribute to optimal mycobactin utilization.

Previously, we constructed an M. smegmatis strain that contains insertions in both fxbA, described above, and mbtD, which encodes a polyketide synthase required for mycobactin synthesis (13). This mutant, which lacks both means of high-affinity iron uptake, does not grow in iron-depleted medium but can be rescued by the addition of purified, iron-bound mycobactin or carboxymycobactin (13). However, the siderophores fail to rescue the fxbA Δesx-3 mutant, suggesting that Esx-3 is required for optimal utilization of iron bound to mycobactins (13). In the absence of the exochelin pathway, deletion of the esx-3 gene eccC3ms, esxGHms, espG3ms, or eccD3ms impairs iron-bound mycobactin utilization in M. smegmatis to an extent similar to that after removal of the entire Esx-3 system, whereas deletion of mycP3ms has a more modest effect (Fig. 3). We conclude that the Esx-3 components EccC3ms, EsxGms/EsxHms, EspG3ms, and EccD3ms are critical to the function of the M. smegmatis Esx-3 system in mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition.

Secretion of EsxHms and EsxGms requires Esx-3 components.

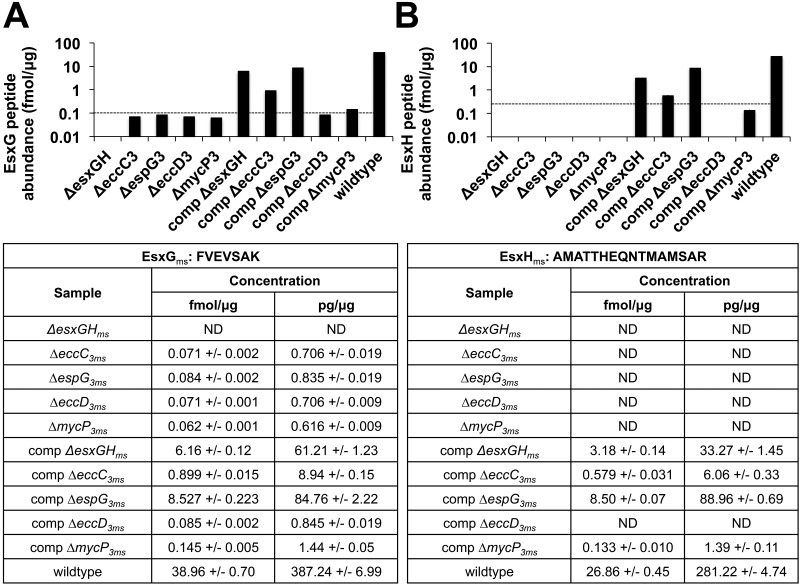

Secretion of EsxB and EsxA is generally linked to Esx-1 function; that is, most mutations that abolish export of these proteins also inhibit virulence (M. tuberculosis and M. marinum) or conjugation (M. smegmatis) (3–5, 35–40). Our work on the Esx-3 system demonstrates that EccC3ms, EsxGms/EsxHms, EspG3ms, and EccD3ms are required for function in mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition and that MycP3ms plays a more limited role (Fig. 2 and 3). Previously, we showed that export of heterologously expressed, myc-tagged EsxH depends on iron levels and on the presence of an intact Esx-3 locus (13). To test whether the loss of individual Esx-3 components similarly influences protein export, we monitored the abundance of representative EsxGms and EsxHms peptides in culture filtrates and selected whole-cell extracts by targeted, quantitative mass spectrometry (MS). Assays for peptides from each of these proteins were constructed using stable-isotope dilution MS (SID-MS) and multiple-reaction-monitoring MS (MRM-MS) (45, 46). For these experiments, we grew strains with intact exochelin production in medium with a level of iron chelation that induces EsxH secretion (13) but does not produce differences in growth. Deletion of the esx-3 gene eccC3ms, esxGHms, espG3ms, or eccD3ms results in supernatant levels of EsxHms and EsxGms that are below the limit of quantitation (LOQ) across two biological replicates (Fig. 4 and S3 to S5 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, although the mycP3ms mutation causes a much smaller defect in low-iron growth than the other mutations (Fig. 2), there is a comparable decrease in supernatant peptides in three of the four data sets to levels below the LOQ (Fig. 4 and S3 to S5).

FIG 4 .

EsxGms (A) and EsxHms (B) abundances in wild-type and esx-3 mutant supernatants. Protein concentrations for EsxGms and EsxHms were approximated, respectively, by measuring the concentration of the FVEVSAK peptide alone and by summing the individual concentrations above the LOD of three of the methionine forms of AMATTHEQNTMAMSAR peptides (Fig. S4). Dotted lines show the LOQ (Fig. S4). The experiments were performed in technical replicate across two biological replicates. The protein abundance data from one of the biological replicates are shown here in graphical and table format, and the data from the other replicate are reported in the Fig. S5 table. comp, complemented; ND, none detected.

We find most of the detectable EsxHms and EsxGms in the supernatant fraction of wild-type M. smegmatis (Fig. 4 and S5). To test whether the observed lack of secretion by the esx-3 mutants reflects a general decrease in protein expression, we also compared the whole-cell extracts of the wild type, ΔespG3ms mutant, and complemented ΔespG3ms strain. The amounts of EsxHms and EsxGms were similar across the samples (Fig. S5), suggesting that the observed change in supernatant abundance accurately reports an export defect. The general lack of protein accumulation in the whole-cell extract, furthermore, implies that the cell tightly regulates the abundance of what we hypothesize is a small, cytoplasmic pool of EsxHms and EsxGms.

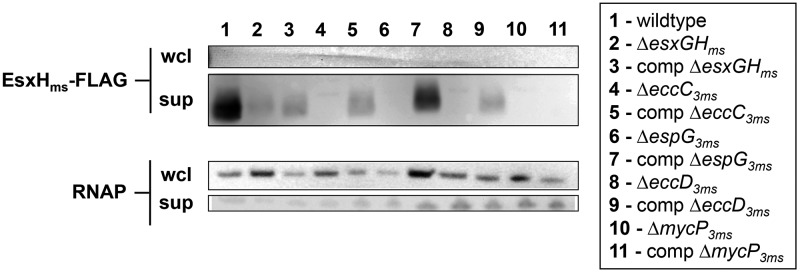

These data were consistent with our previous findings that Esx-3 is required for the export of EsxHms-myc (13). Unlike native EsxGms and EsxHms, however, the tagged protein accumulates in the bacterial cytoplasm to robust levels (13). Therefore, we confirmed the mass spectrometry findings by constructing a new plasmid that constitutively expresses esxGms and FLAG-tagged esxHms and comparable amounts of EsxHms-FLAG in cell-associated and supernatant fractions of wild-type and esx-3 mutant M. smegmatis strains. In agreement with the MRM-MS results, we were consistently unable to detect EsxHms-FLAG from the supernatants of the ΔeccC3ms, ΔespG3ms, ΔeccD3ms, and ΔmycP3ms mutants or from any of the whole-cell extracts (Fig. 5).

FIG 5 .

Export of epitope-tagged EsxHms in the presence or absence of Esx-3 components. Anti-FLAG immunoblotting of whole-cell lysates (wcl) and culture supernatants (sup) from wild-type and esx-3 M. smegmatis containing pSYMP-esxGHms-FLAG in low-iron medium. All strains contain either the empty pJEB402 vector or pJEB402 containing the complementing gene. The antibody against the intracellular protein RNAP is a loading and lysis control. The experiment was performed twice with similar results.

DISCUSSION

We found that EccC3ms, EspG3ms, and EccD3ms are core Esx-3 components that are required for both mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition and EsxGms and EsxHms export. The M. tuberculosis homologs EccC3mt, EspG3mt, and EccD3mt are all predicted to be necessary for in vitro growth (20, 47, 48). The Esx-1 paralogs EccCa1/EccCb1, EspG1, and EccD1 are required for virulence in pathogenic mycobacteria and conjugation in M. smegmatis and, with the exception of EspG1mt (35, 42), for EsxB and EsxA export (3–5, 35–40).

We have also identified a potential accessory Esx-3 component, MycP3, that is necessary for EsxG and EsxH export (Fig. 4 and 5) but not absolutely required for mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition (Fig. 2 and 3). The first observation is not unexpected, as mutants that lack MycP1 fail to secrete EsxB and EsxA (36, 41). The data on the contribution of MycP to Esx function are less clear; although MycP1ms is required for DNA transfer in M. smegmatis to the same or greater extent as other Esx-1 components (4, 36), mycP1mt disruption in M. tuberculosis results in a delayed phenotype in mice compared to the phenotypes resulting from transposon insertions in other esx-1 genes (49). More recent work corroborates an in vivo growth defect from loss of MycP1mt (41), but the lack of a direct comparison to other esx-1 mutant strains precluded analysis of the relative defect. Like the other esx-3 genes, mycP3mt is essential for M. tuberculosis growth in vitro (47). Given that MycP1 and MycP3 likely have different substrate specificities (41, 50, 51), it may be that the relative importance of MycP as an Esx component varies according to the secretion apparatus with which it associates.

Despite our attempts to avoid polar effects by constructing in-frame, unmarked, full gene deletions, it is possible that the mutations altered the expression of downstream genes. However, this does not appear to be the case for at least the ΔmycP3ms mutant, as neither mycP3ms alone nor mycP3ms alongside the downstream eccE3ms restored EsxHms-FLAG export (not shown). Transcription of the esx-3 locus varies according to iron and zinc availability (13, 21, 22). It is possible that expression of the complementing genes from a heterologous, constitutive promoter altered the stoichiometry of Esx-3 components, which in turn resulted in suboptimal protein secretion.

We attempted to measure secreted proteins using native antibodies and Western blotting. However, the antisera that we were able to obtain had low affinity and poor specificity, making quantitation difficult. Given the tendency of secretion systems to be refractory to reporter fusions (52), we turned to MRM-MS to measure bacterial protein export. This label-free method is highly specific and sensitive and is likely to have broad applicability to bacterial protein secretion studies (53).

Precise quantitation of secretion by MRM-MS revealed a surprising dynamic range in the levels of EsxG and EsxH export that support iron acquisition. We were able to restore esx-3 mutant growth to wild-type levels by adding iron to the growth medium (Fig. S2) or by complementing the deleted genes (Fig. 2). However, the same genetic constructs varied widely in their abilities to restore EsxGms and EsxHms export (Fig. 4 and 5). Only a fraction of secreted wild-type EsxGms and EsxHms levels appeared necessary for complementation; we observed robust low-iron growth (Fig. 2) concomitant with protein export that spanned 3 orders of magnitude, from <1% to approximately 40% of wild-type levels (Fig. 4). We recently found that the essential drug targets dihydrofolate reductase and d-alanine racemase are present in excess (54). It is possible that wild-type M. smegmatis exports EsxGms and EsxHms at levels much greater than those needed to support low-iron growth. This raises the possibility that the locus has multiple functions, each with different secretion requirements.

Indeed, there is growing appreciation that the relationship between Esx protein export and function is more complex than initially assumed. There are now numerous reports of Esx-1 mutations that attenuate pathogenic mycobacteria without impacting secretion. For example, complementation of the natural esx-1 mutant M. microti (Fig. 1) with a panel of cosmids containing intact or mutant versions of the M. tuberculosis esx-1 region revealed that espF1mt and espG1mt are required for virulence but not EsxBmt and EsxAmt export (35). Deletion of these genes from M. tuberculosis also resulted in attenuation without impacting the secretion of EsxBmt and EsxAmt (42). In a different example, disruption of disulfide bond formation in the Esx-1 substrate EspA attenuated M. tuberculosis virulence but had no effect on EsxBmt or EsxAmt secretion (43). Finally, transposon insertions in espJms, espKms, and espBms impaired conjugation but not EsxBms export (4). In aggregate, these studies show that secretion of EsxB and EsxA is not sufficient for Esx-1 function in virulence.

Recently, Chen and coworkers isolated two point mutations of EspAmt that block EsxBmt and EsxAmt export in vitro but do not attenuate M. tuberculosis (44). Although they did not rule out a role for the host environment in permitting secretion in vivo, these data suggest that export of these proteins, at least in large amounts, may not be strictly required for virulence. Similarly, we found a mutation that inhibits Esx protein secretion but permits partial function: loss of mycP3ms blocked the export of native EsxGms and EsxHms and FLAG-tagged EsxHms (Fig. 4 and 5), yet the fxbA ΔmycP3ms mutant retained some ability to grow in low iron (Fig. 2). We also found that very low quantities of EsxGms and EsxHms secretion were sufficient to reinstate low-iron growth to some of our complemented esx-3 mutants (Fig. 2 and 4). Importantly, dissection of the Esx-3 system in the model organism M. smegmatis allowed us to compare the two phenotypes, EsxG and EsxH export and mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition, under similar in vitro conditions.

Why are not protein secretion and iron utilization completely congruent in our mutant strains? This is especially puzzling given that the genome of M. smegmatis, unlike M. tuberculosis, does not encode the closely related paralogs EsxR and EsxS, which might otherwise be hypothesized to substitute for EsxG and EsxH function (8). One reason may be the existence of multiple Esx substrates, each with its own requirements for export and contributions to function. The roles of EspG and EspB are particularly informative in this regard. Inactivation of the paralogous espG1, espG5, or, as we show in Fig. 4, espG3 gene generally prevents the export of Esx substrate proteins (11, 17, 37, 42). However, in M. tuberculosis, loss of EspG5mt did not produce an obvious phenotype (55), while EspG1mt was required for full virulence but not EsxBmt or EsxAmt secretion (35, 42). Interestingly, EspG1 and EspG5 have been shown to interact specifically with cognate Pro-Glu (PE)/Pro-Pro-Glu (PPE) proteins (56, 57) and have been proposed to serve as chaperones for Esx secretion of these substrates (57). These data suggest that the PE/PPE proteins have export requirements and functional contributions distinct from those of other type VII substrates. Similarly, the secretion and activity of the Esx-1 substrate EspB appear to be independent of EsxA (58, 59) and EsxB (60).

Our data are consistent with at least three general models. It is conceivable that loss of Esx-3 function produces global changes in cell wall structure such that protein localization is affected by changes both in secretion and in the compartment into which translocation occurs. We note that while esx-3 mutants do not have altered sensitivities to SDS, vancomycin, rifampin (Fig. S5), ampicillin, or kanamycin (19), at least when iron is not limiting, we are unable to rule out this model. A second possibility is that Esx-3 secretes a protein or proteins necessary for iron acquisition and that this protein requires the core components EccC3, EccD3, and EspG3 but not EsxG, EsxH, or MycP3 for export. Although it is possible that Esx-3 function in iron acquisition does not require any EsxG and EsxH secretion, we think that this is unlikely given that the fxbA ΔesxGHms strain has a complementable growth phenotype in low iron. A third model is that both EsxG and EsxH are substrates and structural components of or chaperones for the Esx-3 machinery. In this scenario, EsxG and EsxH are exported across the cytoplasmic membrane via EccD3 into the periplasm, where they are poised to deliver yet-unidentified effectors of ferri-mycobactin uptake across the remainder of the cell wall (Fig. 6). If EsxG and EsxH indeed act within or across the mycobacterial envelope, some of the protein detected in the supernatants of broth-grown mycobacteria may represent sloughing of protein associated with the cell wall (33, 34).

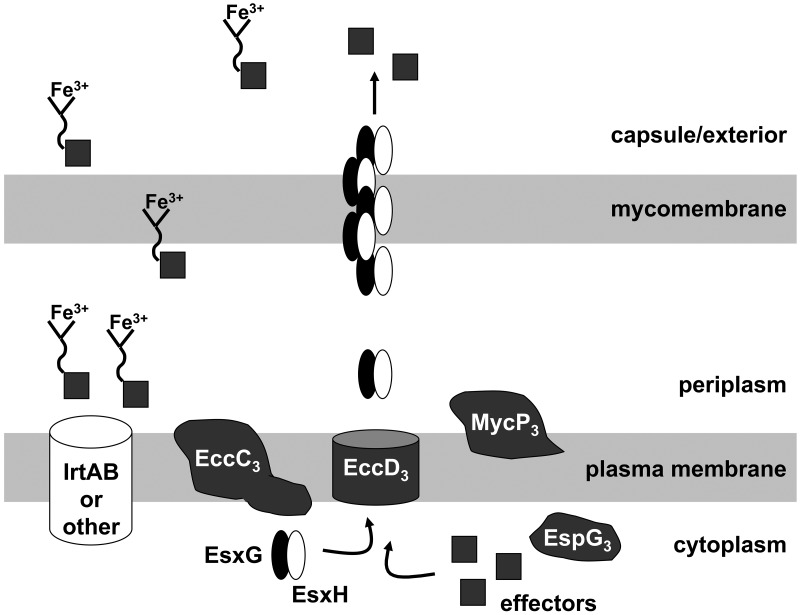

FIG 6 .

One model for Esx-3 function in which EsxG and EsxH are both substrates and chaperones or structural components of the secretion apparatus. IrtA and IrtB are components of a mycobactin transporter system (63–65). We hypothesize that at least one of the functions of EsxG and EsxH is to ferry effectors of iron-loaded mycobactin uptake within or across the mycobacterial cell wall. In the absence of an Esx-3 core component, such as EccD3, we do not detect EsxG or EsxH in culture supernatants. We hypothesize that the proteins are not exported across the cytoplasmic membrane under this condition and therefore are completely unable to contribute to iron acquisition. In contrast, although supernatants from fxbA ΔmycP3ms cultures do not contain detectable EsxG or EsxH, the strain itself retains intermediate growth under low-iron conditions. We suggest the MycP3 protease may be an accessory Esx-3 component that is required either for a stable EsxG-EsxH structure or for optimal chaperone activity. Thus, in the absence of this accessory factor, EsxG and EsxH may still traverse the cytoplasmic membrane to the periplasm but be only partially functional.

While type VII secretion systems have important functions both in vitro and in vivo, their molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Clearly, protein export contributes to but does not entirely account for type VII function. More complete models for type VII structure-function relationships will require better characterization of secreted components and assays for protein-protein interactions that occur between Esx components in the cytosol or membrane (55, 61).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

M. smegmatis was cultured in chelated Sauton’s medium containing 60 ml glycerol, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 2.2 g citric acid monohydrate, 4 g asparagine, and 0.05% Tween 80 per liter. After adjusting the pH to 7.4, the medium was stirred for 1 to 2 days at room temperature with 10 g Chelex 100 resin (Sigma). The medium was filtered, and 1 g MgSO4⋅7H2O was added as a sterile solution. For iron starvation experiments, bacteria were first inoculated from frozen stocks into 7H9 medium, subcultured once in chelated Sauton’s medium, and then diluted 1:1,000 in chelated Sauton’s medium without antibiotics containing either 100 µM 2,2′-dipyridyl or 12.5 µM FeCl3. For mycobactin complementation experiments, bacteria were directly diluted 1:1,000 from a 7H9 starter culture into chelated Sauton’s medium with or without ferri-mycobactin S.

Strain construction.

To create the M. smegmatis esx-3 gene deletions, 1-kb regions flanking eccC3ms, espG3ms, eccD3ms, mycP3ms, and esxGHms were amplified from M. smegmatis genomic DNA, stitched together by PCR, and cloned into the suicide vector pJM1. The pJM1 vector contains a hygromycin-chloramphenicol resistance cassette and the counterselectable marker sacB. M. smegmatis transformants were screened by PCR using primers specific to the flanks as well as to regions within the putative deletion. Candidates were confirmed by PCR using multiple primers outside the flanks. To construct fxbA insertional mutants, the esx-3 deletion strains were transformed with the pSES-fxbA suicide vector (13) and screened by standard methods. The absence of exochelin production was confirmed for candidate mutants by patching them to chrome azurol (CAS) agar.

Complementing constructs for each mutant were constructed by amplifying the regions from genomic M. smegmatis DNA and cloning them under the MOP promoter in the integrative pJEB402 plasmid (38). The construct containing esxGms and esxHms C-terminally tagged with FLAG was generated by amplifying the region from genomic M. smegmatis DNA and cloning it under the control of the hsp60 promoter of pSYMP (62).

SID, MRM-MS. (i) Labeled-peptide internal standards.

Figure S3 shows the amino acid sequences of the proteins EsxGms and EsxHms and the peptides that were selected for quantitative analysis of these proteins by multiple-reaction-monitoring mass spectrometry (MRM-MS). A peptide from each of the proteins was selected based on their detection in the discovery data by high electrospray MS signal responses and because they have unique sequences as determined by a search of the nonredundant M. tuberculosis protein database (NCBI nr). Four different versions of the peptide AMATTHEQNTMAMSAR for the EsxHms protein were selected, all of which were observed in the discovery data.

(ii) Peptide synthesis.

Five signature peptides from the two proteins, EsxGms (FVEVSAK) and EsxHms (AMATTHEQNTMAMSAR, with four forms of differing oxidized methionine states), were synthesized with a single, uniformly labeled [13C6]lysine or [13C6]arginine at their C termini by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). Unlabeled 12C-labeled forms of each peptide were also synthesized by New England Peptide. Synthetic peptides were purified to >99% purity and analyzed by amino acid analysis (New England Peptide). Calculations of concentrations were based upon amino acid analysis.

(iii) MRM-MS assay configuration.

The limits of detection and quantification (LOD and LOQ, respectively) for the signature peptides used to obtain quantitative measurements in each of the 22 samples (5 mutants, 5 complemented mutants and 1 wild-type strain in each of two biological process replicates) are shown in Fig. S4. A 12-point response curve was generated by spiking light peptide versions of the 5 analyte peptides over a range of 0 to 50 fmol/1 µg of digested supernatant protein and a fixed amount of heavy, internal-standard peptides (1 fmol/1 µg) of the supernatant protein mix from the ΔesxGHms sample. This supernatant of the ΔesxGHms sample was used as the background matrix for response curve generation, as it does not express the proteins of interest. Each concentration point was analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)–MRM-MS on a Waters Xevo TQ mass spectrometer (Milford, MA) in three technical replicates. The LOD was determined by the Linnet statistical method, and the lower LOQ was calculated as 3 times the LOD. The blank sample consists of the ΔesxGHms sample with only the isotopically labeled (heavy) peptides spiked in.

(iv) Nano-LC–MRM-MS.

Tryptic peptides were prepared from culture supernatants (see below) and reconstituted in 80 µl of 0.1% formic acid, and 1 µg/µliter of each sample was used for MRM-MS analysis. Nano-LC–MRM-MS was performed on a Xevo TQ mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) coupled to a Nano Acuity LC system. Chromatography was performed with solvent A (0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (100% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid). Each sample was injected with a full-loop injection of 1 µl on a Waters, packed, Reprosil, 3-µm-bead column (75-µm internal diameter [ID], 10-µm ID tip opening) with a 2.5-in by 20-µm ID spray needle. Sample was eluted at 300 nl/min, with a gradient of 3 to 7% solvent B for 8 min, 7 to 40% solvent B for 34 min, and 40 to 90% solvent B for 3 min, with a total data acquisition time of 80 min. Data were acquired with a stable column temperature of 35°C. Collision energy (CE) was optimized for the maximum transmission and sensitivity of each MRM transition by LC–MRM-MS. Three transitions were monitored per peptide and acquired at unit resolution both in the first and in the third quadrupole (Q1 and Q3). In general, transitions were chosen based upon relative abundance and a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) greater than the precursor m/z in the full-scan tandem MS (MS/MS) spectrum recorded on the Xevo TQ mass spectrometer. The final MRM-MS method consisted of 10 optimized transitions for each of the five selected peptides from the two target proteins. One of the four peptides (AMATTHEQNTMAMSAR) was not used for data analysis due to a weak signal.

(v) MRM-MS data analysis.

Data analysis was performed using the Skyline Software Module (https://skyline.gs.washington.edu/). The relative ratios of the three transitions selected and optimized for the final MRM assay were predefined in the absence of the target proteins (i.e., in buffer) for each peptide using the 13C-labeled internal standards. The most abundant transition for each pair was used for quantification unless interference in this channel was observed. The 12C/13C peak area ratios were used to calculate concentrations of the target peptides in each sample by the following equation: measured concentration = peak area ratio × (1 fmol/µl internal standard).

Sample preparation for MRM-MS analysis.

Strains were inoculated from frozen stocks in 7H9 medium with appropriate antibiotics and grown with shaking for 48 h. The cells were then washed twice in chelated Sauton’s medium, normalized by their optical densities at 600 nm (OD600s), and inoculated 1:500 into chelated Sauton’s medium. Cultures were grown for 48 h to log phase, and 8 OD units were harvested. Bacteria in the pellets were lysed by bead beating, and the lysates were stored at −80°C. Protein from the supernatant was precipitated by the trichloroacetic acid (TCA) method and dissolved in urea-ammonium-bicarbonate buffer (8 M urea, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate). Protein concentration was measured by the Bradford assay of diluted samples.

One hundred micrograms of protein was reduced by 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylated using 50 mM iodoacetamide. Prior to being digested with trypsin, samples were diluted to a urea concentration of 0.6 M by the addition of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Trypsin (Promega Gold) digestion was carried out at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:50. The peptides were desalted using Sep-Pak cartridges (Sep-Pak C18 1-cc [50-mg] Vac cartridges; Waters) as described by the manufacturer. In the final step, samples were eluted in 80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid and evaporated to complete dryness in a vacuum centrifuge.

Immunoblotting.

Strains were inoculated from frozen stocks into 7H9 medium and grown to saturation. They were then diluted 1:500 in chelated Sauton’s medium, grown to saturation, and diluted 1:100 in chelated Sauton’s medium. Proteins from cell pellets and supernatants of cultures grown for 12 h in this fashion were run on 10 to 20% Tris-Tricine gels (Invitrogen) and revealed using an anti-FLAG antibody. An antibody to RNA polymerase (RNAP; Neoclone W0023), an intracellular protein, served as a loading and lysis control.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Confirmation of individual esx-3 deletion mutants by PCR. (A) Primers that amplify within the specified gene (internal) and primers outside the given gene that amplify across (across). Primers to MSMEG_0611 are positive controls; (B) primers outside the specified gene that amplify across. Download

Growth of fxbA and fxbA Δesx-3 M. smegmatis mutants in iron-replete medium. pJ, pJEB402 vector. Representative data from at least three independent experiments are shown. Download

Amino acid sequences of the proteins EsxGms and EsxHms and the peptides selected for quantitative analysis of these proteins by MRM-MS. Download

Limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) for the peptides shown. Values are based on the most abundant interference-free transition ion from each peptide. The units are in fmol or pg of protein per input μg of cell culture protein. Download

Supernatant and whole-cell (wcl) peptide concentrations for one of two biological replicates. ND, the measured peptide concentration was below the limit of detection (LOD). Download

MICs for sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), vancomycin, and rifampin. Log-phase cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 and grown in 7H9 medium containing serial dilutions of the given compound. The MICs were recorded as the lowest concentration of compound that prevented visible growth after 3 days. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice, with the same results. Download

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Colin Ratledge for providing ferri-mycobactin S and Jeff Murry for constructing the pJM1 vector. We gratefully acknowledge the helpful advice and insight from Meera Unnikrishnan, Sarah Fortune, and Jeff Murry. We also thank Mike Burgess for his help in running the MRM-MS assays.

This research was supported in part by the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard (S.A.C.) and by grants to E.J.R. (NIH/NIAID grant 1P01 AI074805-01A1), J.A.P. (NIH/NIAID grant 1R01 AI087682-01A1 and a Clinical Scientist Development Award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation), and M.S. (Research Council of Norway grants 220836/H10 and 223255/F50).

Footnotes

Citation Siegrist MS, Steigedal M, Ahmad R, Mehra A, Dragset MS, Schuster BM, Philips JA, Carr SA, Rubin EJ. 2014. Mycobacterial Esx-3 requires multiple components for iron acquisition. mBio 5(3):e01073-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01073-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lewis KN, Liao R, Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Smith S, Behr MA, Sherman DR. 2003. Deletion of RD1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis mimics Bacille Calmette-Gu érin attenuation. J. Infect. Dis. 187:117–123. 10.1086/345862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pym AS, Brodin P, Brosch R, Huerre M, Cole ST. 2002. Loss of RD1 contributed to the attenuation of the live tuberculosis vaccines Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium microti. Mol. Microbiol. 46:709–717. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pym AS, Brodin P, Majlessi L, Brosch R, Demangel C, Williams A, Griffiths KE, Marchal G, Leclerc C, Cole ST. 2003. Recombinant BCG exporting ESAT-6 confers enhanced protection against tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 9:533–539. 10.1038/nm859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coros A, Callahan B, Battaglioli E, Derbyshire KM. 2008. The specialized secretory apparatus ESX-1 is essential for DNA transfer in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 69:794–808. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06299.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Flint JL, Kowalski JC, Karnati PK, Derbyshire KM. 2004. The RD1 virulence locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulates DNA transfer in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:12598–12603. 10.1073/pnas.0404892101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, III, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544. 10.1038/31159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tekaia F, Gordon SV, Garnier T, Brosch R, Barrell BG, Cole ST. 1999. Analysis of the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in silico. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:329–342. 10.1054/tuld.1999.0220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gey Van Pittius NC, Gamieldien J, Hide W, Brown GD, Siezen RJ, Beyers AD. 2001. The ESAT-6 gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other high G+C Gram-positive bacteria. Genome Biol. 2:RESEARCH0044. 10.1186/gb-2001-2-10-research0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abdallah AM, Savage ND, van Zon M, Wilson L, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, van der Wel NN, Ottenhoff TH, Bitter W. 2008. The ESX-5 secretion system of Mycobacterium marinum modulates the macrophage response. J. Immunol. 181:7166–7175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abdallah AM, Verboom T, Hannes F, Safi M, Strong M, Eisenberg D, Musters RJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Appelmelk BJ, Luirink J, Bitter W. 2006. A specific secretion system mediates PPE41 transport in pathogenic mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 62:667–679. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abdallah AM, Verboom T, Weerdenburg EM, Gey van Pittius NC, Mahasha PW, Jiménez C, Parra M, Cadieux N, Brennan MJ, Appelmelk BJ, Bitter W. 2009. PPE and PE_PGRS proteins of Mycobacterium marinum are transported via the type VII secretion system ESX-5. Mol. Microbiol. 73:329–340. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06783.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Serafini A, Boldrin F, Palù G, Manganelli R. 2009. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESX-3 conditional mutant: essentiality and rescue by iron and zinc. J. Bacteriol. 191:6340–6344. 10.1128/JB.00756-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Siegrist MS, Unnikrishnan M, McConnell MJ, Borowsky M, Cheng TY, Siddiqi N, Fortune SM, Moody DB, Rubin EJ. 2009. Mycobacterial Esx-3 is required for mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:18792–18797. 10.1073/pnas.0900589106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sweeney KA, Dao DN, Goldberg MF, Hsu T, Venkataswamy MM, Henao-Tamayo M, Ordway D, Sellers RS, Jain P, Chen B, Chen M, Kim J, Lukose R, Chan J, Orme IM, Porcelli SA, Jacobs WR., Jr. 2011. A recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis induces potent bactericidal immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 17:1261–1268. 10.1038/nm.2420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ilghari D, Lightbody KL, Veverka V, Waters LC, Muskett FW, Renshaw PS, Carr MD. 2011. Solution structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis EsxG-EsxH complex: functional implications and comparisons with other M. tuberculosis Esx family complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 286:29993–30002. 10.1074/jbc.M111.248732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abdallah AM, Bestebroer J, Savage ND, de Punder K, van Zon M, Wilson L, Korbee CJ, van der Sar AM, Ottenhoff TH, van der Wel NN, Bitter W, Peters PJ. 2011. Mycobacterial secretion systems ESX-1 and ESX-5 play distinct roles in host cell death and inflammasome activation. J. Immunol. 187:4744–4753. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Daleke MH, Cascioferro A, de Punder K, Ummels R, Abdallah AM, van der Wel N, Peters PJ, Luirink J, Manganelli R, Bitter W. 2011. Conserved Pro-Glu (PE) and Pro-Pro-Glu (PPE) protein domains target LipY lipases of pathogenic mycobacteria to the cell surface via the ESX-5 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 286:19024–19034. 10.1074/jbc.M110.204966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mehra A, Zahra A, Thompson V, Sirisaengtaksin N, Wells A, Porto M, Koster S, Penberthy K, Kubota Y, Dricot A, Rogan D, Vidal M, Hill DE, Bean AJ, Philips JA. 2013. Mycobacterium tuberculosis type VII secreted effector EsxH targets host ESCRT to impair trafficking. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003734. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Serafini A, Pisu D, Palu G, Rodriguez GM, Manganelli R. 2013. The ESX-3 secretion system is necessary for iron and zinc homeostasis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 8:e78351. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. 2003. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 48:77–84. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rodriguez GM, Voskuil MI, Gold B, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. 2002. ideR, an essential gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of IdeR in iron-dependent gene expression, iron metabolism, and oxidative stress response. Infect. Immun. 70:3371–3381. 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3371-3381.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maciag A, Dainese E, Rodriguez GM, Milano A, Provvedi R, Pasca MR, Smith I, Palù G, Riccardi G, Manganelli R. 2007. Global analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Zur (FurB) regulon. J. Bacteriol. 189:730–740. 10.1128/JB.01190-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ratledge C, Dover LG. 2000. Iron metabolism in Pathogenic Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:881–941. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ratledge C, Ewing M. 1996. The occurrence of carboxymycobactin, the siderophore of pathogenic mycobacteria, as a second extracellular siderophore in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 142:2207–2212. 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodriguez GM. 2006. Control of iron metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 14:320–327. 10.1016/j.tim.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones CM, Niederweis M. 2010. Role of porins in iron uptake by Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 192:6411–6417. 10.1128/JB.00986-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tullius MV, Harmston CA, Owens CP, Chim N, Morse RP, McMath LM, Iniguez A, Kimmey JM, Sawaya MR, Whitelegge JP, Horwitz MA, Goulding CW. 2011. Discovery and characterization of a unique mycobacterial heme acquisition system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:5051–5056. 10.1073/pnas.1009516108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones CM, Niederweis M. 2011. Mycobacterium tuberculosis can utilize heme as an iron source. J. Bacteriol. 193:1767–1770. 10.1128/JB.01312-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bitter W, Houben EN, Bottai D, Brodin P, Brown EJ, Cox JS, Derbyshire K, Fortune SM, Gao LY, Liu J, Gey van Pittius NC, Pym AS, Rubin EJ, Sherman DR, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2009. Systematic genetic nomenclature for type VII secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000507. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abdallah AM, Gey van Pittius NC, Champion PA, Cox J, Luirink J, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Appelmelk BJ, Bitter W. 2007. Type VII secretion—mycobacteria show the way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:883-891. 10.1038/nrmicro1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Champion PA, Cox JS. 2007. Protein secretion systems in Mycobacteria. Cell. Microbiol. 9:1376–1384. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simeone R, Bottai D, Brosch R. 2009. ESX/type VII secretion systems and their role in host-pathogen interaction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:4–10. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacGurn JA, Raghavan S, Stanley SA, Cox JS. 2005. A non-RD1 gene cluster is required for Snm secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1653–1663. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04800.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fortune SM, Jaeger A, Sarracino DA, Chase MR, Sassetti CM, Sherman DR, Bloom BR, Rubin EJ. 2005. Mutually dependent secretion of proteins required for mycobacterial virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:10676–10681. 10.1073/pnas.0504922102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brodin P, Majlessi L, Marsollier L, de Jonge MI, Bottai D, Demangel C, Hinds J, Neyrolles O, Butcher PD, Leclerc C, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2006. Dissection of ESAT-6 system 1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and impact on immunogenicity and virulence. Infect. Immun. 74:88–98. 10.1128/IAI.74.1.88-98.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Converse SE, Cox JS. 2005. A protein secretion pathway critical for Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence is conserved and functional in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 187:1238–1245. 10.1128/JB.187.4.1238-1245.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gao LY, Guo S, McLaughlin B, Morisaki H, Engel JN, Brown EJ. 2004. A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1677–1693. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Mathur SK, Zakel KL, Grotzke JE, Lewinsohn DM, Smith S, Sherman DR. 2004. Individual RD1-region genes are required for export of ESAT-6/CFP-10 and for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 51:359–370. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03844.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hsu T, Hingley-Wilson SM, Chen B, Chen M, Dai AZ, Morin PM, Marks CB, Padiyar J, Goulding C, Gingery M, Eisenberg D, Russell RG, Derrick SC, Collins FM, Morris SL, King CH, Jacobs WR., Jr. 2003. The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:12420–12425. 10.1073/pnas.1635213100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stanley SA, Raghavan S, Hwang WW, Cox JS. 2003. Acute infection and macrophage subversion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis require a specialized secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:13001-13006. 10.1073/pnas.2235593100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ohol YM, Goetz DH, Chan K, Shiloh MU, Craik CS, Cox JS. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis MycP1 protease plays a dual role in regulation of ESX-1 secretion and virulence. Cell Host Microbe 7:210–220. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bottai D, Majlessi L, Simeone R, Frigui W, Laurent C, Lenormand P, Chen J, Rosenkrands I, Huerre M, Leclerc C, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2011. ESAT-6 secretion-independent impact of ESX-1 genes espF and espG1 on virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 203:1155–1164. 10.1093/infdis/jiq089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Garces A, Atmakuri K, Chase MR, Woodworth JS, Krastins B, Rothchild AC, Ramsdell TL, Lopez MF, Behar SM, Sarracino DA, Fortune SM. 2010. EspA acts as a critical mediator of ESX1-dependent virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by affecting bacterial cell wall integrity. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000957. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen JM, Zhang M, Rybniker J, Basterra L, Dhar N, Tischler AD, Pojer F, Cole ST. 2013. Phenotypic profiling of Mycobacterium tuberculosis EspA point mutants reveals blockage of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 secretion in vitro does not always correlate with attenuation of virulence. J. Bacteriol. 195:5421–5430. 10.1128/JB.00967-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Addona TA, Shi X, Keshishian H, Mani DR, Burgess M, Gillette MA, Clauser KR, Shen D, Lewis GD, Farrell LA, Fifer MA, Sabatine MS, Gerszten RE, Carr SA. 2011. A pipeline that integrates the discovery and verification of plasma protein biomarkers reveals candidate markers for cardiovascular disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 29:635–643. 10.1038/nbt.1899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gillette MA, Carr SA. 2013. Quantitative analysis of peptides and proteins in biomedicine by targeted mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 10:28–34. 10.1038/nmeth.2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Griffin JE, Gawronski JD, Dejesus MA, Ioerger TR, Akerley BJ, Sassetti CM. 2011. High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002251. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang YJ, Ioerger TR, Huttenhower C, Long JE, Sassetti CM, Sacchettini JC, Rubin EJ. 2012. Global assessment of genomic regions required for growth in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002946. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. 2003. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:12989-12994. 10.1073/pnas.2134250100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wagner JM, Evans TJ, Chen J, Zhu H, Houben EN, Bitter W, Korotkov KV. 2013. Understanding specificity of the mycosin proteases in ESX/type VII secretion by structural and functional analysis. J. Struct. Biol. 184:115–128. 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Solomonson M, Huesgen PF, Wasney GA, Watanabe N, Gruninger RJ, Prehna G, Overall CM, Strynadka NC. 2013. Structure of the mycosin-1 protease from the mycobacterial ESX-1 protein type VII secretion system. J. Biol. Chem. 288:17782–17790. 10.1074/jbc.M113.462036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McCann JR, McDonough JA, Pavelka MS, Braunstein M. 2007. Beta-lactamase can function as a reporter of bacterial protein export during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of host cells. Microbiology 153:3350–3359. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/008516-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Champion MM, Williams EA, Kennedy GM, Champion PA. 2012. Direct detection of bacterial protein secretion using whole colony proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11:596–604. 10.1074/mcp.M112.017533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wei JR, Krishnamoorthy V, Murphy K, Kim JH, Schnappinger D, Alber T, Sassetti CM, Rhee KY, Rubin EJ. 2011. Depletion of antibiotic targets has widely varying effects on growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4176–4181. 10.1073/pnas.1018301108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bottai D, Di Luca M, Majlessi L, Frigui W, Simeone R, Sayes F, Bitter W, Brennan MJ, Leclerc C, Batoni G, Campa M, Brosch R, Esin S. 2012. Disruption of the ESX-5 system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes loss of PPE protein secretion, reduction of cell wall integrity and strong attenuation. Mol. Microbiol. 83:1195–1209. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Teutschbein J, Schumann G, Möllmann U, Grabley S, Cole ST, Munder T. 2009. A protein linkage map of the ESAT-6 secretion system 1 (ESX-1) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Res. 164:253-259. 10.1016/j.micres.2006.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Daleke MH, van der Woude AD, Parret AH, Ummels R, de Groot AM, Watson D, Piersma SR, Jiménez CR, Luirink J, Bitter W, Houben EN. 2012. Specific chaperones for the type VII protein secretion pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 287:31939–31947. 10.1074/jbc.M112.397596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chen JM, Zhang M, Rybniker J, Boy-Röttger S, Dhar N, Pojer F, Cole ST. 2013. Mycobacterium tuberculosis EspB binds phospholipids and mediates EsxA-independent virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 89:1154–1166. 10.1111/mmi.12336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Champion PA, Champion MM, Manzanillo P, Cox JS. 2009. ESX-1 secreted virulence factors are recognized by multiple cytosolic AAA ATPases in pathogenic mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 73:950–962. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06821.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McLaughlin B, Chon JS, MacGurn JA, Carlsson F, Cheng TL, Cox JS, Brown EJ. 2007. A mycobacterium ESX-1-secreted virulence factor with unique requirements for export. PLoS Pathog. 3:e105. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Houben EN, Bestebroer J, Ummels R, Wilson L, Piersma SR, Jiménez CR, Ottenhoff TH, Luirink J, Bitter W. 2012. Composition of the type VII secretion system membrane complex. Mol. Microbiol. 86:472-484. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Festa RA, McAllister F, Pearce MJ, Mintseris J, Burns KE, Gygi SP, Darwin KH. 2010. Prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [corrected]. PLoS One 5:e8589. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Farhana A, Kumar S, Rathore SS, Ghosh PC, Ehtesham NZ, Tyagi AK, Hasnain SE. 2008. Mechanistic insights into a novel exporter-importer system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis unravel its role in trafficking of iron. PLoS One 3:e2087. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rodriguez GM, Smith I. 2006. Identification of an ABC transporter required for iron acquisition and virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 188:424–430. 10.1128/JB.188.2.424-430.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ryndak MB, Wang S, Smith I, Rodriguez GM. 2009. Mycobacterium tuberculosis high affinity iron importer, IrtA, contains an FAD-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 192:861–869. 10.1128/JB.00223-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confirmation of individual esx-3 deletion mutants by PCR. (A) Primers that amplify within the specified gene (internal) and primers outside the given gene that amplify across (across). Primers to MSMEG_0611 are positive controls; (B) primers outside the specified gene that amplify across. Download

Growth of fxbA and fxbA Δesx-3 M. smegmatis mutants in iron-replete medium. pJ, pJEB402 vector. Representative data from at least three independent experiments are shown. Download

Amino acid sequences of the proteins EsxGms and EsxHms and the peptides selected for quantitative analysis of these proteins by MRM-MS. Download

Limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) for the peptides shown. Values are based on the most abundant interference-free transition ion from each peptide. The units are in fmol or pg of protein per input μg of cell culture protein. Download

Supernatant and whole-cell (wcl) peptide concentrations for one of two biological replicates. ND, the measured peptide concentration was below the limit of detection (LOD). Download

MICs for sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), vancomycin, and rifampin. Log-phase cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 and grown in 7H9 medium containing serial dilutions of the given compound. The MICs were recorded as the lowest concentration of compound that prevented visible growth after 3 days. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice, with the same results. Download