Abstract

Purpose

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) can adversely affect fine motor control of the hand. Precision pinch between the thumb and index finger requires coordinated movements of these digits for reliable task performance. This study examined the impairment upon precision pinch function affected by CTS during digit movement and digit contact.

Methods

Eleven CTS subjects and 11 able-bodied (ABL) controls donned markers for motion capture of the thumb and index finger during precision pinch movement (PPM). Subjects were instructed to repetitively execute the PPM task, and performance was assessed by range of movement, variability of the movement trajectory, and precision of digit contact.

Results

The CTS group demonstrated shorter path-length of digit endpoints and greater variability in inter-pad distance and most joint angles across the PPM movement. Subjects with CTS also showed lack of precision in contact points on the digit-pads and relative orientation of the digits at contact.

Conclusions

Carpal tunnel syndrome impairs the ability to perform precision pinch across the movement and at digit-contact. The findings may serve to identify deficits in manual dexterity for functional evaluation of CTS.

Keywords: Carpal tunnel syndrome, precision pinch, kinematics

1 Introduction

Individuals with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) often suffer from numbness, tingling, pain, and clumsiness of the hand 1. These symptoms lead to notable impairments in the ability to perform fine motor tasks involving the thumb and index finger, thereby reducing quality of life by compromising the ability to execute activities of daily living such as manipulating buttons, writing, and using utensils 2. CTS is caused by compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel, but its etiology is not always readily evident and may develop from various precipitating factors including repetitive manual work, genetics, pregnancy, and injury 3. Treatment of CTS is often predicated on clinicians’ clinical assessment and patients’ performance at examination, and current diagnosis methods such as nerve conduction, imaging, sensation tests, and clinical maneuvers can produce inconclusive results 4; 5. Further reducing the reliance upon either subjective or qualitative measures for clinical assessment of CTS pathology upon hand function may improve diagnosis, which can also serve as a long-term objective of functional motion analysis of the hand.

Median nerve compression incites sensorimotor dysfunction of the digits of the hand, most notably the thumb and index finger 1. Since clinical tests for CTS typically evaluate symptoms and physiological consequences rather than function, examining the ramifications of median nerve impairment on coordinated force generation and movement of the hand is in need and has been attempted. Although diminished thumb abduction strength has been considered to be associated with CTS 6; 7, it was also shown that multi-directional force production at the thumb is largely preserved with CTS 8.When median a nerve block was administered to produce acute median neuropathy, several studies have reported decreases in grip strength and force production of the thumb 9-11. The ability to adjust submaximal force during precision grip also appears to be notably afflicted by median neuropathy 12; 13. While CTS may diminish force-coordination of grip, neuropathic effects on the ability to skillfully move the digits also can limit dexterous manipulation of objects.

The precision pinch movement (PPM) task signifies a functional daily task that focally involves the thumb and index finger to prepare for grasp and manipulation of small objects 14. Since the median nerve has notable motor (first and second lumbricals) and sensory (palmar-side sensation) innervation to the thumb and index finger, the PPM is well-posed for studying median nerve dysfunction. Previous studies have demonstrated deficiencies in PPM execution in the presence of median nerve dysfunction. Similar to behavior following anesthesia-block of the median nerve 15, it was observed that CTS individuals performing PPM exhibited increased variability of the tip positions and joint angles of the thumb and index finger at contact 16. However, the inability to precisely locate the digits would be preceded by deficit in dynamic control of the digits during the movement. Therefore, assessing the performance of the movement function of the thumb and index finger may better illuminate the sensorimotor deficit induced during functional tasks in response to median nerve dysfunction.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the trajectory kinematics of the thumb and index finger during PPM for individuals with CTS in addition to contact. Specifically, PPM is defined by the consistent and coordinated bringing together of the thumb and index finger pads into contact from an initially, open-hand configuration. While free of force constraints, this task specifically pertains to the basic movement capabilities of the digits affected by CTS. Characterizing differences in movement features during PPM for individuals with CTS versus healthy, able-bodied (ABL) controls demonstrates the functional consequences of CTS and provides insight into the related patho-mechanism.

We hypothesized that the sensorimotor deficit associated with CTS would produce pathokinematics of the thumb and index finger which reflect degraded movement performance. The variables characterized in this study indicate the capacity and consistency to perform the PPM movements from which to assess the dysfunction associated with CTS. Specifically, CTS would lead to impairment of precision pinch function with the following characteristics: (1) general movement restriction quantified by inter-pad distance, (2) relative increase in index finger path-length as compared to thumb path-length, (3) increased variability in pinch trajectory, (4) increased variability of the orientation angle between the distal segments of the thumb and index finger, and (5) decreased precision of digit-pad contact. For parameter (2), we initially expected that while path-length for both digits may decrease with CTS, the index-finger may act to compensate for the pronounced loss in thumb function following median nerve impairment 11. Confirmation of these hypotheses could serve as kinematic hallmarks of the impact of CTS on hand function.

2 Methods

Human Subjects

Subjects were age- and gender-matched between the two population groups of ABL (able-bodied) and CTS (carpal tunnel syndrome). Twenty-two subjects (11 ABL, 11 CTS) between the ages of 35-64 years participated in this study. Subjects volunteered after initially being informed of the study by their consulting physicians and then contacting our study coordinator for further details. Each group consisted of 9 females and 2 males with mean age of 49.5 ± 9.6 years for CTS and 48.6 ± 7.6 years for ABL. The subject distribution across gender and age in this study is consistent with notably higher incidence of confirmed CTS among women with mean age near 50 years 17. All participants were right-hand dominant, verified by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory 18. The CTS subjects were diagnosed upon positive confirmation of the following criteria: 1) history of parathesias, pain, and/or numbness in the median innervated hand territory persisting for at least 3 months; 2) positive provocative maneuvers including Tinel’s sign, Phalen’s test, and/or median nerve compression test; 3) abnormal electrodiagnostic testing consistent with median nerve neuropathy at/or distal to the wrist 19; 4) an overall CTS Severity Questionnaire 2 score greater than 1.5; (5) positive diagnosis according to clinical discretion 1. The ABL subjects did not previously report or demonstrate a history of disease, injury, or previous complications involving the hand and upper extremity. CTS and control subjects exclusion criteria included: 1) electrodiagnostic tests, which indicate ulnar, radial, or proximal median neuropathy; 2) existence of a central nervous system disease (e.g., multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, Parkinson’s disease); 3) pregnancy; 4) history of trauma or surgical intervention to the hand/wrist; 5) rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis of the hand/wrist; 6) diabetes; 7) recent steroid injection to the hand. The mean pinch strength values across the ABL and CTS subjects were 57.2±18N and 53.1±18N, respectively. All participants signed an informed consent approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Collection of Marker Position Data

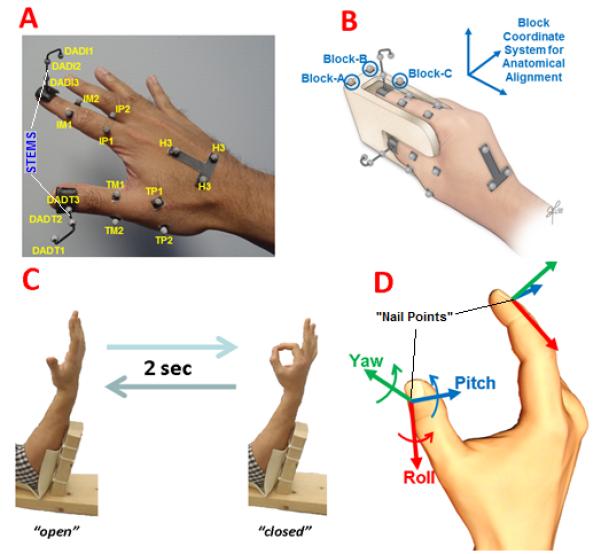

Retro-reflective markers were affixed to the dorsal surface of the right hand of each subject to derive thumb and index finger kinematics. The 3-D position of each marker was tracked at 100Hz using a motion capture system (Model 460, Vicon Motion Systems and Peak Performance, Inc., Oxford, UK). A marker set established in our laboratory was employed to compute joint kinematics with considerations of anatomical alignment (Figure 1A) 20. To explicitly define the position and orientation of the distal digit segment of the thumb and index finger, the marker set included a nail marker-cluster employed with a digit alignment device (DAD, Figure 1B) 21. The long-axis of the nail-cluster stem was approximately in-line with the central prominence of the finger-pad. The DAD block accommodates most hand sizes such that subjects typically are able to position the index finger and thumb along the long-axis of the block and palmar-side of the digits flush on the respective block planes. The marker-cluster on the back of the hand placed along the second metacarpal served as the local reference frame for the hand. It was assumed that the second metacarpal would serve as a stable proximal reference for both the index finger and thumb in order to utilize a minimal set of markers in computing angular kinematics 22.

Figure 1.

Experimental set-up A) Markers utilized for motion tracking and computing digit kinematics 20 B) Calibration using a digit alignment device 21 C) Subject with arm-support cyclically performing 2-sec cycle of precision pinch movement (markers not shown) D) Aligned axes about which relative rotation of distal thumb with respect to distal index finger defines distal orientation coordination angle (DOCA).

Note: Origin of axes located at respective “nail-point” estimated from the respective nail marker-cluster, which subsequently serves as center for digit-pad sphere model.

Experimental Protocol

After subjects donned the marker set and underwent the calibration procedure described in 20; 21, each subject performed trials involving consecutive cycles of PPM at a metronome pace to allow for performing a PPM cycle in 2 sec. For a cycle of PPM, a subject placed their arm in a splint (Figure 1C), while transitioning their hand from the open (all digits comfortably extended to maximally separate thumb and index finger-pads) to closed (thumb and index finger pads contacting in tip-pinch) back to open configuration. The subject initially was in the open position. After the “go” command, the subject would smoothly transition to the closed position following a metronome beep so as to reach the closed position on the following beep then smoothly return to open on the third beep to complete the cycle. The subject continued to perform a total of 10 consecutive PPM cycles to mark the end of the trial. The subject first underwent 5 practice trials with eyes open to accommodate to the protocol. The subject subsequently performed 5 test trials (10 cycles per trial) while visual feedback was blocked with an opaque sleeping mask to prevent visual compensation of proprioceptive deficit 23. Each subject was instructed to perform each cycle of PPM as naturally, but as consistently similar, as possible. A one-minute rest was provided between consecutive trials. All subjects reported not having notably worsened pain while performing the experiment compared to any pain or discomfort they felt prior to the session commencing.

Computation of Digit Kinematics

The protocol for computing joint angles from this marker set followed that described in 22. For adjacent segments of the same digit, aligned axes of rotations about the X, Y, and Z-axes were assumed to correspond to anatomical extension(+)/flexion(-), abduction(+)/adduction (-), and internal(+)/external(-) rotation, respectively, following the ISB (International Society of Biomechanics) convention 24. The joint angle degrees of freedom (DOFs) being characterized were the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) extension/flexion and abduction/adduction, proximal interphalangeal (PIP) extension/flexion, and distal interphalangeal (DIP) extension/flexion joints of the index finger. For the thumb, the DOFs included the interphalangeal (IP) extension/flexion, MCP extension/flexion abduction/adduction, and carpometacarpal (CMC) extension/flexion, abduction/adduction, and internal/external rotation. To assess relative orientation of the distal segments, the distal orientation coordination angle (DOCA) was defined as the Euler angles of the distal thumb segment relative to the distal index segment (Figure 1D). Rotations with respect to the distal index segment coordinate system about the X, Y, and Z-axes were denoted as Pitch, Yaw, and Roll, respectively 21. Ultimately, the three DOCA rotations comprehensively describe how the thumb is oriented relative to the index finger during the PPM. It should be noted that for the CMC joint, which connects the first metacarpal to the trapezium, the second metacarpal was used as a reference surrogate for the trapezium. This was done with the assumption that relative changes in orientation between the trapezium and second metacarpal would be minimal to obtain sufficiently accurate estimations of presumed pure rotations about orthogonal axes of rotation at the CMC joint according to convention specified in 22. The presumed axes of CMC rotation are orthogonal to those defined by the block coordinate system seen in (Figure 1B). Specifically, CMC extension/flexion, abduction/adduction, and internal/external rotation occur about axes pointing medially, dorsally, and proximally to the long-axis of the first metacarpal.

Computation of the Precision of Digit-Pad Contact

Using each nail marker-cluster (Figure 1A) as a reference for an aligned 3-D coordinate system (Figure 1B), a spherical model of the respective digit-pad was represented. A virtual “nail-point” is computed as a projection along the marker-cluster stem to the dorsal surface of the nail and served as the respective sphere “center”. Using digital calipers, the digit thickness was measured as the transverse distance from dorsal surface to digit-pad prominence of the distal segment for both the thumb and index finger and served as the sphere “radius”. The shortest distance between the digit-pad surfaces was subsequently denoted as “inter-pad” distance. The contact between the thumb and index finger was estimated to occur at initial intersection between the virtual spheres. A circular area of contact points (from multiple trials) projected upon each subject’s digit-pad model surface was also computed. The center of this contact area was the mean point of contact location, and the radius was the mean distance away from this location across all trials.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between the ABL and CTS groups were made using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon non-parametric test for variables. These variables include movement range, pinch contact location, and pinch contact DOCA. For comparing trial-to-trial trajectory variability, a paired t-test was used for mean trial-to-trial variability. Trajectory variability was defined as the 1 standard deviation (s.d.) band about the mean trajectory for each subject across equally-spaced points defined for each pinch cycle (i.e., open → closed → open). The initial open-portion of each pinch cycle was defined to begin at a local maximum observed in inter-pad distance for the corresponding PPM cycle that is one standard deviation greater than the mean inter-pad distance across all cycles for a given subject. When comparing between groups, the variability for one group should be “normalized” to be on the same scale of the other group since absolute variability generally increases proportionally with range of movement. Thus, the normalization factor multiplying the variability of group B to scale to group A is range(A)/range(B). To consider differences in hand sizes, variables of inter-pad distance and digit path-lengths were normalized by respective subject palm width.

In summary, the movement parameters being calculated include mean trajectory range (R), mean trial-to-trial trajectory variability (V), mean-value at contact (MC), and variability at contact (VC). The kinematic variables being observed with corresponding parameter calculations are as follows: inter-pad distance (R, V), joint angles (R, V), pinch contact location (MC, VC), and distal orientation coordination angle (R, V, MC, VC).

3 Results

The range for inter-pad distance across the PPM cycle was larger for ABL than CTS (Figure 2). On average, the peak inter-pad distance for CTS subjects was 26% lower than that for ABL subjects (p<0.01). In comparison to the ABL subjects, the CTS subjects had 16% greater cycle-to-cycle variability across the pinch trajectories (p<0.01). The three-dimensional (3-D) path-length values of the thumb and index finger nail-points across the PPM cycle for the ABL and CTS groups are shown in Figure 3. The path-length was significantly greater for the ABL than CTS groups for both the thumb (p<0.05) and index finger (p<0.001). On average, the ratio of index-to-thumb path-length for the CTS subjects (2.87±1.7) was greater than the ABL subjects (2.09±0.8), but the difference was not significant according to a two-sample t-test (p=0.17).

Figure 2.

LEFT: Mean trajectory (solid lines) and cycle variability (dashed lines) across condition types: ABL = able-bodied subject, CTS = carpal tunnel syndrome subject. RIGHT: Bar plots comparing range and range-normalized trajectory variability for ABL versus CTS.

Note: **p<0.01, distance normalized by “palm width”

Figure 3.

Bar plots comparing index and thumb path-lengths (left, middle) and ratio of index to thumb path-length (right) for ABL versus CTS.

Note: *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, distance normalized by “palm width”

The mean range and variability (based on the +/- 1 s.d. about the mean trajectory) values for the joint-DOF angles observed over the pinch cycle, and denoting of significant differences between ABL and CTS, are shown in the bar graphs of Figure 4. Overall, the angular ranges were greater for ABL than CTS, and significant differences (p<0.05) were found for Thumb-MCP extension/flexion (Δ = 17.0°), Index-MCP extension/flexion (Δ = 18.6°), and DOCA-Roll (Δ = 45.2°). For variability, significant increases were observed for CTS among the thirteen angular trajectories (p<0.001) reported except Thumb-CMC extension/flexion (no significant difference, p=0.10), Thumb-CMC abduction/adduction (decrease, p<0.01), and DOCA-Pitch (decrease, p<0.01).

Figure 4.

The range (R) and variability (V) between ABL and CTS for angular excursions at corresponding degrees-of-freedom (DOFs) are shown for comparison. Across all 13 DOF trajectories being observed, the CTS group demonstrated reduced range and greater variability at 12 and 10 DOFs, respectively.

The precision of pinch contact over all repetitive trials is described by the contact areas depicted in Figure 5 for both the ABL and CTS groups. The contact area on both digits was greater for the CTS group, and the area for the index finger was found to be significant (p<0.05) (Table 1). In comparing differences in mean contact location between ABL and CTS groups, the absolute difference in each X-Y-Z location dimension for each digit was not significantly different (p>0.05). For relative digit orientation at contact, only the DOCA-Roll component demonstrated a significant difference (p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Mean contact location and area on spherical models for thumb and index finger shown for ABL (blue) and CTS (red) groups relative to respective nail XYZ coordinate systems.

Note: contact area circle radius equals mean distance of contact points across all trials about mean contact point location (circle center).

Table 1.

Relative position and orientation of distal segments of digits at contact (mean across all subjects)

| Thumb-Pad (mm) | Index Finger-Pad (mm) | DOCA (deg) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | Area (mm2) | X | Y | Z | Area (mm2) | Pitch | Yaw | Roll | |

| ABL | 3.8±2 | −8.1±3 | −9.1±2 | 9.1±5 | −5.6±2 | −7.8±3 | −3.7±3 | 6.3±4 | 82±27 | −11±29 | 128±9 |

| CTS | 4.1±3 | −8.3±3 | −8.2±3 | 13.3±14 | −6.7±2 | −8.2±1 | −1.5±4 | 18.0±16 | 69±18 | −3±23 | 109±13 |

| Δ(CTS-ABL) | 0.3 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 4.2 | −1.1 | −0.4 | 2.2 | 11.7* | −13 | 8 | −19* |

Note: indicates significant difference between ABL and CTS at p<0.05

4 Discussion

In this study, the effects of CTS on the ability to perform precision pinch movement were investigated and compared to the ABL group by observing differences in (1) movement range, (2) variability of the dynamic movement, and (3) digit configuration at digit contact. The CTS group generally demonstrated reduced performance across these measures compared to the ABL controls. These quantitative observations support the central notion that CTS focally compromises movement dexterity during precision pinch function.

The physiological effects of CTS on functional precision pinch movements can be profound. Chronic symptoms of pain and tingling can produce motor behavior that promotes passive tissue rigidity and a functional disincentive to actively challenge the extremes of the ranges of movement 25. This phenomenon is supported by our finding that individuals with CTS demonstrated reduced range of inter-pad distance despite having similar pinch strength of the ABL group. Decreased inter-pad distance is a hallmark of the dynamic portion of the pinch task as it describes the overall effects of CTS on the functional ability to separate and bring the digits together in a coordinated manner. The reduction in inter-pad distance range can be attributed to a movement deficit at each individual digit as the path-lengths of the digit nail-points for both the thumb and index finger were reduced for the CTS group.

The significant deficit in range of inter-pad and path-length distances would also indicate a general reduction in range of the angle excursions at the contributing digit joints. Significant reductions in range due to CTS were indeed observed for extension/flexion of the MCP joint for both digits. Deficit at the MCP joint of the index finger may be explained by compromised median nerve innervation to the first lumbrical muscle, which inserts on the radial extensor mechanism near the MCP joint. Compromised motor output of this muscle may explain limited movement at the MCP joint, which as the most proximal joint in the kinematic chain of the index finger consequently reduced path-length of the index nail-point. However, CTS subjects did exhibit similar pinch strength as the ABL subject group. Therefore, if muscle-based contributions to ROM deficit exist, it may be more attributable to issues with sensory feedback such that muscles are being sub-maximally activated. Reduced range of movement at the thumb may be due to CTS effects on the thenar muscles (opponens pollicis, abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis) which produces flexion at the MCP and basal joint of the thumb. The range for DOCA-Roll was also significantly lower with CTS, and this observation is likely due to impaired median nerve innervation of the same thenar muscles which inadequately pronate the thumb into opposition with the index finger. The diminished movement range observed in this CTS study was prevalent across joints than observed by 15 following acute median nerve block. We observed reductions in movement range for all joint DOFs with CTS, while 15 reported notable compensatory increases in thumb-MCP, index-PIP, and index-DIP joint motions. This suggests that the restricted movement with CTS is not only due to sensorimotor dysfunction of the median nerve but may also entail chronic structural changes in conjunction with pain effects. With CTS, stiffening of soft tissue structures of the hand, such as myofascia, may lead to undesirable passive joint rigidity stemming from less daily movement due to persistent sensorimotor dysfunction.

Because the median nerve facilitates function of the muscles of the thenar eminence 26, we hypothesized that the effects on thumb path-length would be relatively greater to those of the index finger. For each group, path-length was expectedly greater for the index finger than the thumb since the index finger is capable of more versatile changes in posture that demonstrates its relatively greater role in thumb-index co-manipulation 27. The index-to-thumb path-length ratio was, on average, 32% greater for the CTS group, however, this difference was not observed to be significant, possibly due to the relatively small sample size and unequal variance. A statistical power analysis indicated that 41 subjects are needed to detect the difference.

While reduction in the range of movement is a clear and evident functional outcome of CTS, the effects of CTS on movement precision and coordination require examination of more kinematic details. In this study, the functional deficit from CTS was characterized by assessing the trajectory variability of the dynamic portions of the pinch movement in addition to pinch contact. Measurements at contact indicate an end result of the movement, but the functional impairment from CTS can manifest during the movement as well. While 16 suggested CTS increased the digit position variability at contact, the current study examined the cyclic variability of the index finger and thumb across the entire pinch movement trajectory. The CTS group exhibited increased dyscoordination in terms of significantly higher dynamic (or trajectory) variability for joint angles (7 out of 10), inter-pad distance, and DOCA (Yaw, Roll). This inability to consistently coordinate during the pinching motion prior to or following contact may result from sensorimotor dysfunction yielding both reduced motor output and compromised sensory feedback in dynamically regulating motor function 28.

At pinch contact, anecdotal increases in variability of the distal segments of the grasping digits with median nerve dysfunction were observed as similarly reported in 15; 16. Since differences were more notably observed in movement trajectories rather than in contact location, it may signify a compensatory adaptation by individuals with CTS to better locate their digits at pinch termination despite sensorimotor deficit throughout the movement. However, a significant decrease in the contact precision on the index finger with CTS was still demonstrated. A decreasing trend in thumb contact precision was also shown, although it was statistically insignificant. The decreased contact precision on the index finger could be related to impaired coordination between both the thumb and index finger. However, it may be focally attributable to dysfunction of the first lumbrical because its musculo-tendon unit has focal contribution to dynamic index finger action 29. The lumbricals act via the dorsal aponeurosis to control and enhance the stability of finger motion 30. Furthermore, the onus of the index finger to undergo larger excursions and changes in posture than the thumb make it more susceptible to undergoing variable contact. Since greater kinematic variability may accrue across the longer trajectories of the index finger, there is likely more inconsistency in converging upon the same contact location. Given the change in contact area, as expected, differences in the relative orientation of the distal digit segments (i.e., DOCA) were also observed. The DOCA-roll component was significantly lower for CTS, which may again indicate a compromised motor ability to reliably rotate the thumb in opposition to the index finger 31.

Compared to the previous studies investigating precision pinch contact, our study utilized a more stable reference for the digit end-points fixed to the nail 21, rather than the hand. This consideration in conjunction with a presumed spherical model for the digit-pad serves as a more rigorous measurement tool than direct placement of a marker on the digit. However, this methodology is still a limited approximation of the finger-pad. The true finger-pad is not perfectly spherical and has mechanical compression characteristics that also contribute to cutaneous sensation and regulation of motor performance 32. However, the geometrical model and parameters utilized in this study allows effective quantification and visualization to distinguish ABL and CTS groups on a functional level.

While CTS has notable effects at the MCP and CMC-basilar joint of the thumb and the MCP joint of the index finger, the relative functional effects of CTS upon the respective digits can be assessed from movement characteristics of the distal segments of the digits. In this study, we observed that ranges of movement and the path-lengths of the nail-points for both digits diminished with CTS. Furthermore, CTS led to increased variability in the movement of these digits in addition to subsequent variation of contact between the finger-pads. These results outline functional consequences of CTS upon movement of the digits in subsequent manipulation of objects. Limited ranges of movement suggest a reduced functional workspace while increased variability during the movement and contact indicate inability to efficiently operate within that workspace. As such, this provides a kinematic basis for manual clumsiness that extends beyond deficits in grip and pinch forces commonly used for functional evaluation for CTS.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01AR056964 from NIAMS/NIH. The authors would also like to thank Tamara Marquardt for coordinating recruitment of human subjects.

6 References

- 1.Keith MW, Masear V, Chung K, et al. Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:389–396. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200906000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine DW, Simmons BP, Koris MJ, et al. A self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of severity of symptoms and functional status in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1585–1592. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelsen H, Posner MA. Medical history of carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 2002;18:257–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0712(01)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amadio PC, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, et al. Outcome assessment for carpal tunnel surgery: the relative responsiveness of generic, arthritis-specific, disease-specific, and physical examination measures. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21:338–346. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(96)80340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bland JD. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:167–171. doi: 10.1002/mus.20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Partecke JT, Borkowski N, Dombert T, et al. Specific strength measurement of musculus abductor pollicis brevis in order to objectively evaluate muscle regeneration after carpal tunnel release surgery. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38:296–299. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu F, Carlson L, Watson HK. Quantitative abductor pollicis brevis strength testing: reliability and normative values. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25:752–759. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li ZM, Harkness DA, Goitz RJ. Thumb strength affected by carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:320–326. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000181143.93681.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boatright JR, Kiebzak GM. The effects of low median nerve block on thumb abduction strength. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:849–852. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozin SH, Porter S, Clark P, et al. The contribution of the intrinsic muscles to grip and pinch strength. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24:64–72. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.1999.jhsu24a0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li ZM, Harkness DA, Goitz RJ. Thumb force deficit after lower median nerve block. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2004;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nowak DA, Hermsdorfer J, Marquardt C, et al. Moving objects with clumsy fingers: how predictive is grip force control in patients with impaired manual sensibility? Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:472–487. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe BD, Freivalds A. Effect of carpal tunnel syndrome on grip force coordination on hand tools. Ergonomics. 1999;42:550–564. doi: 10.1080/001401399185469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domalain M, Vigouroux L, Danion F, et al. Effect of object width on precision grip force and finger posture. Ergonomics. 2008;51:1441–1453. doi: 10.1080/00140130802130225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li ZM, Nimbarte AD. Peripheral median nerve block impairs precision pinch movement. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:1941–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gehrmann S, Tang J, Kaufmann RA, et al. Variability of precision pinch movements caused by carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, et al. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA. 1999;282:153–158. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens JC, Smith BE, Weaver AL, et al. Symptoms of 100 patients with electromyographically verified carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:1448–1456. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199910)22:10<1448::aid-mus17>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nataraj R, Li ZM. Integration of marker and force data to compute three-dimensional joint moments of the thumb and index finger digits during pinch. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2013 doi: 10.1080/10255842.2013.820722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen ZL, Mondello TA, Nataraj R, et al. A digit alignment device for kinematic analysis of the thumb and index finger. Gait Posture. 2012;36:643–645. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nataraj R, Li ZM. Robust identification of three-dimensional thumb and index finger kinematics with a minimal set of markers. J Biomech Eng. 2013;135:91002–91009. doi: 10.1115/1.4024753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghez C, Gordon J, Ghilardi MF. Impairments of reaching movements in patients without proprioception. II. Effects of visual information on accuracy. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:361–372. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu G, van der Helm FC, Veeger HE, et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion--Part II: shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. J Biomech. 2005;38:981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverstein BA, Fine LJ, Armstrong TJ. Occupational factors and carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11:343–358. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700110310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman KR, An KN, Litchy WJ, et al. In-vivo function of the thumb muscles. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1999;14:141–150. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokogawa R, Hara K. Manipulabilities of the index finger and thumb in three tip-pinch postures. J Biomech Eng. 2004;126:212–219. doi: 10.1115/1.1691444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebied AM, Kemp GJ, Frostick SP. The role of cutaneous sensation in the motor function of the hand. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:862–866. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leijnse JN, Kalker JJ. A two-dimensional kinematic model of the lumbrical in the human finger. J Biomech. 1995;28:237–249. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00070-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Schroeder HP, Botte MJ. The dorsal aponeurosis, intrinsic, hypothenar, and thenar musculature of the hand. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001:97–107. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200102000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monzee J, Lamarre Y, Smith AM. The effects of digital anesthesia on force control using a precision grip. Journal of neurophysiology. 2003;89:672–683. doi: 10.1152/jn.00434.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moberg E. The role of cutaneous afferents in position sense, kinaesthesia, and motor function of the hand. Brain. 1983;106(Pt 1):1–19. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]