Abstract

A recent paper by Sirois et al. in The Journal of Experimental Medicine reports that the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) promotes uptake of DNA into endosomes and lowers the immune recognition threshold for the activation of Toll-like receptor 9. Two crystal structures suggested that the DNA phosphate-deoxyribose backbone is recognized by RAGE through well-defined interactions. However, the electron densities for the DNA molecules are weak enough that the presented modeling of DNA is questionable, and models only containing RAGE account for the observed diffraction data just as well as the RAGE–DNA complexes presented by the authors.

To the Editor:

The structures of the RAGE–DNA complexes suggested that the DNA phosphate-deoxyribose backbone interacts with dimers of the RAGE ectodomain through intermolecular hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions or indirectly through water molecules (Sirois et al., 2013). Explicit and detailed RAGE–DNA interactions are shown in Fig. 3 of the Sirois et al. paper. One DNA site is described as being located at the N-terminal V domain of RAGE, whereas a second site is located at the junction of the RAGE V and C1 domains. These findings have also been highlighted by a comment in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology (Chen, 2013). However, the JEM paper did not contain a figure illustrating the electron density for the DNA, neither in the main text nor in the supplemental material. We therefore analyzed the RCSB protein data bank entries 3S58 and 3S59 underlying the presented structural work. Both contain a double-stranded DNA molecule with 22 bps and 2 copies of the RAGE ectodomain V–C1 fragment.

We noticed that the temperature factors for the DNA molecules are much higher (270 Å2) than for the protein (88 Å2), and standard 2mFo-DFc electron density maps calculated from the deposited coordinates and reflection files did not reveal significant density for the DNA in either of the entries. In particular, there is virtually no density for the electron-dense phosphate groups, even at a contour level of 1σ, whereas the density for the two RAGE molecules is of the quality to be expected for protein structures determined from diffraction data at 2.8 and 3.1 Å resolution. Despite this, there is no mention by the authors that the electron density for DNA is weak. This contrasts a recent structure of the mouse RAGE V–C1 fragment in complex with a bound heparin dodecasaccharide determined at 3.5 Å resolution, where the electron density is likewise weak and discontinuous for the heparin molecule (Xu et al., 2013). But here the heparin molecule is not deposited in the resulting entry 4IM8.

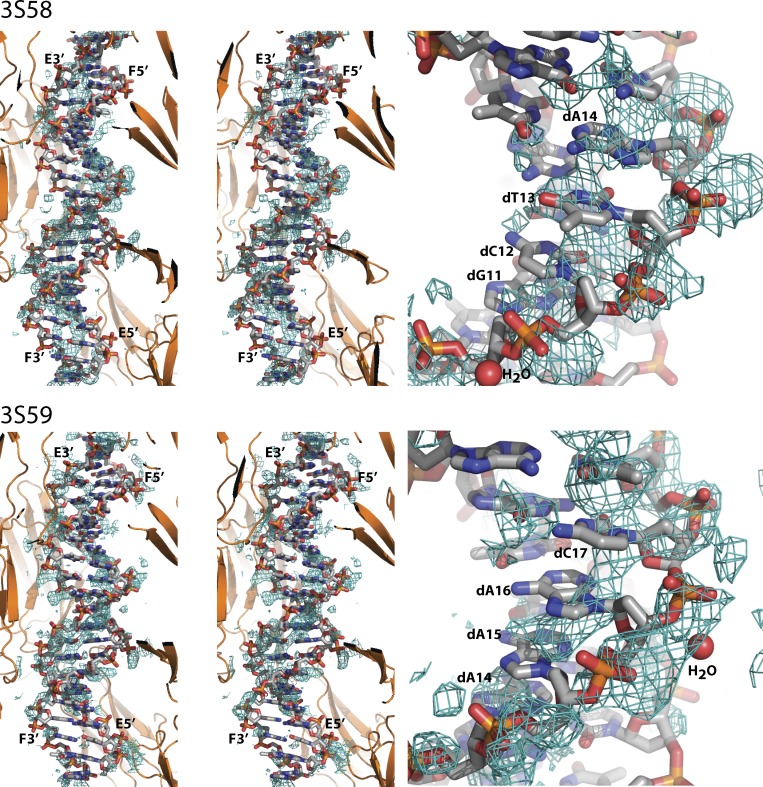

To test whether DNA significantly contributes to the observed diffraction data, we removed DNA, water molecules and ligands from the two entries leaving only RAGE molecules. We then performed standard refinement of atom positions, individual temperature factors and TLS parameters using PHENIX.REFINE (Adams et al., 2010). Throughout refinement, coordinates and temperature factors of the two copies of V and C1-domains were restrained by noncrystallographic symmetry. Our structure obtained by refinement against the 3S59 diffraction data were used as a reference model for refinement against the 3S58 data. The R-values after refinement measure the agreement between the observed diffraction data and the data calculated from the atomic model. Compared with the two structures presented in the JEM paper, we obtained fully comparable R/Rfree values, a better stereochemistry, and significantly smaller Rfree–R differences, indicating less over-fitting of the model (Table 1). Hence, the observed data can be explained nearly as well or better when DNA, water molecules, and ligands corresponding to 23% of the atoms (including 44 very electron-rich phosphorous atoms) are removed. Furthermore, the resulting omit 2mFo-DFc and mFo-DFc electron density maps we calculated based on the resulting models do not indicate density into which a double-stranded DNA molecule can be modeled (Fig. 1), and formation of the crystal lattice does not require DNA for either entry.

Table 1.

Comparison of refinement statistics for the models containing RAGE, DNA, ligands and water molecules reported by Sirois et al. with our refinement of a model only containing RAGE

| RCSB entry | 3S58 | 3S59 |

| Resolution (Å) | 3.1 | 2.8 |

| R/Rfree (%)(Sirois et al., 2013) | 19.1/23.1 | 19.6/23.8 |

| R/Rfree (%) (this study) | 22.0/24.0 | 22.0/23.5 |

| Rmsd bonds (Å)/angles (°) (Sirois et al., 2013) | 0.008/0.975 | 0.007/0.982 |

| Rmsd bonds (Å)/angles (°)(This study) | 0.002/0.673 | 0.002/0.627 |

| Atoms | ||

| Protein/DNA/water/ligands (Sirois et al., 2013) | 3274/896/16/45 | 3267/896/16/59 |

| Protein (this study) | 3274 | 3267 |

R-factor = Σh|Fo|-|Fc|/Σh|Fo|, where Fc is the calculated structure factor scaled to Fo. Rfree is identical to R-factor on a subset of test reflections not used in refinement. Coordinates for the rerefined structures are deposited at the RCSB protein data bank as entries 4OFV and 4OF5.

Figure 1.

Omit 2mFo-DFc electron density maps, contoured at 0.8σ, calculated after refinement of models devoid of DNA, water, and ligands against the deposited diffraction data. To the left, a stereo view for both structures showing the entire DNA double helix. The surrounding RAGE molecules are shown in cartoon representation. Only density within 4 Å of the shown DNA is displayed. The 5′- and 3′-ends of the two DNA chains E and F are labeled. To the right, a close-up of a selected region from each structure in which some density is observed that might represent backbone phosphates, but the density for the bases (labeled by nucleotide) does not allow sequence assignment. In both panels, DNA and water molecules (labeled H2O) were taken from the two coordinate entries, whereas the RAGE molecules result from our rerefinement against the deposited diffraction data.

Collectively, the diffraction data deposited by Sirois et al. (2013) do not support the presence of DNA in the analyzed crystals in a specific position, and their detailed description of the RAGE–DNA interaction, including even water-mediated contacts, may not be justified. The weak density evident in our omit electron density maps suggests that dsDNA could be present at rather low occupancy and possibly also in multiple orientations relative to RAGE (Fig. 1). The paper by Sirois et al. (2013) contains other lines of evidence for the significance of the RAGE–DNA interaction, and because the RAGE V–C1 tandem domain has a strongly positively charged surface patch suitable for interaction with nucleic acids and other negative ligands as previously discussed (Fritz, 2011; Yatime and Andersen, 2013), it is quite likely that DNA binding to RAGE is through the V–C1 domain tandem. This is also supported by mutagenesis data presented in Fig. 3 of the paper (Sirois et al., 2013). However, this may not involve specific and well-defined RAGE–DNA contacts; instead, it may be governed by overall and degenerated electrostatic attraction between DNA and RAGE akin to the RAGE–Heparin interaction (Xu et al., 2013).

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., et al. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:213–221 10.1107/S0907444909052925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I. 2013. DNA is all the RAGE. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20:1242–1242 10.1038/nsmb.2714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz G. 2011. RAGE: a single receptor fits multiple ligands. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36:625–632 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirois C.M., Jin T., Miller A.L., Bertheloot D., Nakamura H., Horvath G.L., Mian A., Jiang J., Schrum J., Bossaller L., et al. 2013. RAGE is a nucleic acid receptor that promotes inflammatory responses to DNA. J. Exp. Med. 210:2447–2463 10.1084/jem.20120201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Young J.H., Krahn J.M., Song D., Corbett K.D., Chazin W.J., Pedersen L.C., Esko J.D. 2013. Stable RAGE-heparan sulfate complexes are essential for signal transduction. ACS Chem. Biol. 8:1611–1620 10.1021/cb4001553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatime L., Andersen G.R. 2013. Structural insights into the oligomerization mode of the human receptor for advanced glycation end-products. FEBS J. 280:6556–6568 10.1111/febs.12556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]