Abstract

When carbon sources become limiting for growth, bacteria must choose which of the remaining nutrients should be used first. We have identified a nutrient-sensing signaling network in Escherichia coli that is activated at the transition to stationary phase. The network is composed of the two histidine kinase/response regulator systems YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB and their target proteins, YjiY and YhjX (both of which are membrane-integrated transporters). The peptide/amino acid-responsive YehU/YehT system was found to have a negative effect on expression of the target gene, yhjX, of the pyruvate-responsive YpdA/YpdB system, while the YpdA/YpdB system stimulated expression of yjiY, the target of the YehU/YehT system. These effects were confirmed in mutants lacking any of the genes for the three primary components of either system. Furthermore, an in vivo interaction assay based on bacterial adenylate cyclase detected heteromeric interactions between the membrane-bound components of the two systems, specifically, between the two histidine kinases and the two transporters, which is compatible with the formation of a larger signaling unit. Finally, the carbon storage regulator A (CsrA) was shown to be involved in posttranscriptional regulation of both yjiY and yhjX.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli contains 30 histidine kinases (HKs) and 32 response regulators (RRs) (1), some of which are still not very well understood. The YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB systems have recently been characterized in more detail in our laboratory (2, 3). Both HKs and RRs are over 30% identical at the amino acid sequence level and share the same pattern of structural domains (4, 5). Both of these two-component systems comprise an LytS-like HK and an LytTR-like RR and thus belong to the LytS/LytTR family. Many bacterial pathogens express LytS/LytTR family members that regulate crucial host-specific mechanisms during infection of their human and plant hosts (6). LytS HKs harbor at least five transmembrane helices (5TMs) within the input domain of the 5TM Lyt (LytS-YhcK) type (4). In addition, YehU and YpdA each possess a GAF domain, which is potentially capable of binding cyclic GMP, proteins, or ions (7, 8), although its function remains unclear in most of the proteins in which it is found (9). The YehU/YehT system is activated in response to the presence of peptides or amino acids (2), while the available evidence suggests that the stimulus sensed by YpdA is pyruvate (3).

YehT and YpdB are each composed of an N-terminal CheY-like receiver domain and a C-terminal LytTR-like effector domain with DNA-binding affinity (10). Under activating conditions, YehT induces yjiY, which codes for a transporter belonging to the CstA superfamily (2). YpdB regulates the expression of yhjX, which encodes a transporter of unknown function belonging to the major facilitator superfamily (3).

In this study, we demonstrate that these two systems are functionally interconnected. In vivo reporter studies detected crosswise stimulus-dependent alterations in the expression of their respective target genes, and mutational analyses revealed that deletion of any of the components of the signal transduction cascade affects the function of the other. Furthermore, in vivo protein-protein interaction assays suggest that both systems together form a single large signaling unit. Finally, the carbon storage regulator A (CsrA) was found to serve as an additional checkpoint, regulating the expression of both yjiY and yhjX at the posttranscriptional level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides.

The E. coli strains used in this study and their genotypes are listed in Table 1. Mutants were constructed by using an E. coli Quick-and-Easy gene deletion kit (Gene Bridges) and a BAC modification kit (Gene Bridges), as reported elsewhere (11). Both kits rely on the Red/ET recombination technique. The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1, and oligonucleotide sequences are available on request. DNA fragments for plasmid construction were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| MG1655 | F− λ− ilvG rfb50 rph-1 | 33 |

| MG3 | MG1655 rpsL150 ΔyehT::rpsL-neo Kanr Strs | 2 |

| MG6 | MG1655 rpsL150 ΔyehU::rpsL-neo Kanr Strs | 2 |

| MG22 | MG1655 rpsL150 ΔypdB::rpsL-neo Kanr Strs | 3 |

| MG23 | MG1655 rpsL150 ypdA-H371Q Kans Strr | 3 |

| MG26 | MG1655 ΔyhjX | 3 |

| MG31 | MG1655 ΔyjiY | This work |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | 34 |

| BTH101 | F− cyaA-99 araD139 galE15 galK16 rpsL1 hsdR2 mcrA1 mcrB1 | 35 |

| DH5α | F− endA1 glnV44 thi-1 recA1 relA1 gyrA96 deoR nupG ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 hsdR17(rK− mK+) λ− | 36 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1-MCS5-TT-RBS-lux | luxCDABE and terminators bacteriophage lambda T0 and rrnB1 T1 cloned into pBBR1-MCS5 for plasmid-based transcriptional fusions, Gmr | 37 |

| pBBR yjiY-lux | PyjiY−212/+88a cloned in the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pBBR1-MCS5-TT-RBS-lux, Gmr | 2 |

| pBBR yhjX-lux | PyhjX−264/+36 cloned in the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pBBR1-MCS5-TT-RBS-lux, Gmr | 3 |

| pBBR yjiY′-lux | PyjiY−212/+187 cloned in the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pBBR1-MCS5-TT-RBS-lux, Gmr | This work |

| pBBR yhjX′-lux | PyhjX−264/+135 cloned in the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pBBR1-MCS5-TT-RBS-lux, Gmr | This work |

| pBAD24 | Arabinose-inducible pBAD promoter, pBR322 ori, Ampr | 38 |

| pBAD24-CsrA | csrA cloned in the EcoRI and SphI sites of pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pBAD24-CsrB | csrB cloned in the EcoRI and SphI sites of pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pBAD24-CsrC | csrC cloned in the EcoRI and SphI sites of pBAD24, Ampr | This work |

| pUT18 | Expression vector, Ampr | 14 |

| pUT18C | Expression vector, Ampr | 14 |

| pKT25 | Expression vector, Kanr | 14 |

| pKNT25 | Expression vector, Kanr | 14 |

| pUT18C-zip | Control plasmid, N-terminal CyaA-T18-yeast leucine zipper fusion, Ampr | 14 |

| pKT25-zip | Control plasmid, N-terminal CyaA-T25-yeast leucine zipper fusion, Kanr | 14 |

| pUT18-gene | Gene of interest cloned in XbaI and BamHI sites of pUT18, resulting in C-terminal CyaA-T18-protein fusions (T18-gene) | This work |

| pUT18C-gene | Gene of interest cloned in XbaI and BamHI sites of pUT18C, resulting in N-terminal CyaA-T18-protein fusions (gene-T18) | This work |

| pKT25-gene | Gene of interest cloned in XbaI and BamHI sites of pKT25, resulting in N-terminal CyaA-T25-protein fusions (gene-T25) | This work |

| pKNT25-gene | Gene of interest cloned in XbaI and BamHI sites of pKNT25, resulting in C-terminal CyaA-T25-protein fusions (T25-gene) | This work |

Numbers are according to the transcriptional start site of the corresponding gene.

Molecular biological techniques.

Plasmid DNA and genomic DNA were isolated using a HiYield plasmid minikit (Suedlaborbedarf) and a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen), respectively. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels using a HiYield PCR cleanup and gel extraction kit (Suedlaborbedarf). Q5 DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) was used according to the supplier's instructions. Restriction enzymes and other DNA-modifying enzymes were also purchased from New England BioLabs and used according to the manufacturer's directions.

Growth conditions.

E. coli MG1655 strains (Table 1) were grown overnight in lysogeny broth (LB) or M9 minimal medium with 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose as the C source. After inoculation, bacteria were routinely grown in LB medium or M9 minimal medium with the C sources indicated below under agitation (200 rpm) at the designated temperature. For solid medium, 1.5% (wt/vol) agar was added. Where appropriate, media were supplemented with antibiotics (ampicillin sodium salt, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin sulfate, 50 μg/ml; gentamicin sulfate, 50 μg/ml; streptomycin, 50 μg/ml).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR.

At the time points indicated below, cells were harvested, and total RNA was isolated essentially as described previously (12) and treated with DNase I for 30 min to remove residual chromosomal DNA. Subsequently, the RNA was purified using an RNA Pure kit (Suedlaborbedarf) and used as the template for randomly primed first-strand cDNA synthesis according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR; iQ5 real-time PCR detection system; Bio-Rad) was performed using the synthesized cDNA, a SYBR green detection system (Bio-Rad), and internal primers specific for yjiY, yhjX, and recA. Duplicate samples from three independent biological experiments were used, and the cycle threshold (CT) value was determined after 40 cycles using iQ software (Bio-Rad). Values were normalized with reference to the value for recA, and relative changes in transcript levels were calculated using the comparative CT method (13).

In vivo protein-protein interaction studies using BACTH.

Protein-protein interactions were assayed with the bacterial adenylate cyclase-based two-hybrid system (BACTH) essentially as described previously (14). E. coli BTH101 was transformed with different pUT18C and pKNT25 derivatives (Table 1) to test for interactions. We used LysP fusion constructs (15) to exclude false-positive results, whereas leucine zipper fusion constructs were used to test assay functionality (Table 1). Cells were grown under aeration overnight in LB medium supplemented with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 30°C and harvested for determination of β-galactosidase activities, which are expressed in Miller units (16).

In vivo expression studies.

In vivo expression of yhjX and yjiY was quantified by means of luciferase-based reporter gene assays, using E. coli MG1655 cells that had been transformed with plasmid pBBR yjiY-lux, pBBR yhjX-lux, pBBR yjiY′-lux, or pBBR yhjX′-lux (Table 1).

Cells of an overnight culture grown in M9 minimal medium with 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose as the C source were inoculated into M9 minimal medium (supplemented with pyruvate or Casamino Acids [20 mM or 0.4%]) to give a starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05. Cells were then incubated under aerobic growth conditions at 37°C, and the OD600 and luminescence were measured continuously. The optical density was determined in a microplate reader (Tecan Sunrise) at 600 nm. Luminescence levels were determined in a luminescence reader (Centro LB960; Berthold Technology) for 0.1 s and are reported as relative light units (RLU; counts s−1).

RESULTS

Evidence for cross-activation of the target genes of the YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB systems.

YehT- and YpdB-dependent genes were identified in two transcriptome studies in which the corresponding RRs were overproduced (2, 3). Overproduction of YehT was found to induce expression of yjiY but also correlated with repression of yhjX. However, while YehT bound tightly to the yjiY promoter, little or no binding of YehT to the yhjX promoter was detectable, ruling out the possibility that the latter gene is a direct target of the YehU/YehT system (2). Unexpectedly, our subsequent studies identified yhjX as the sole direct target of the YpdA/YpdB system. Moreover, overproduction of YpdB resulted in a 4-fold induction of yjiY, in spite of the fact that YpdB bound very poorly, if at all, to its promoter region (3) (see Fig. 6). These results suggested functional interconnectivity between the YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB systems, and the present study was designed to analyze this issue in more detail.

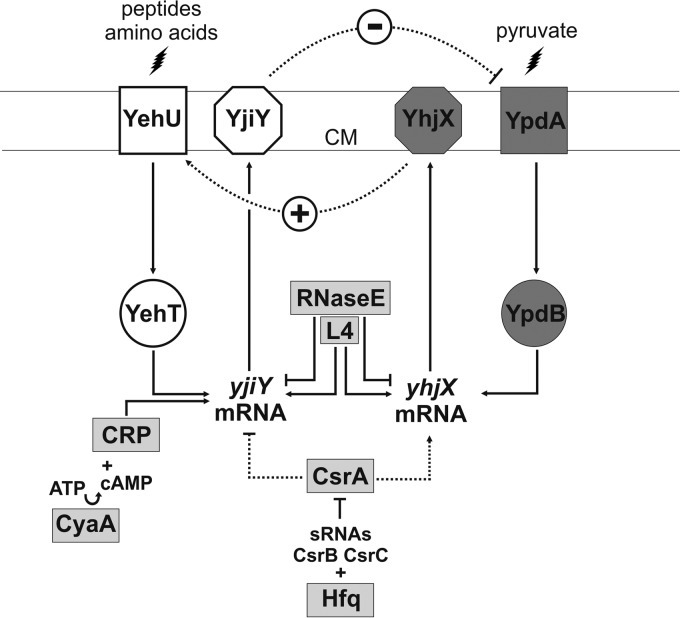

FIG 6.

Model for the nutrient-sensing histidine kinase/response regulator network in Escherichia coli. The scheme summarizes the interconnectivity between the two histidine kinase/response regulator systems YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB and their target transporter proteins, YjiY and YhjX, the influence of the global regulators CRP and CsrA, and the impact of L4/RNase E on target gene expression. Activating (↑) or inhibitory (⊥) effects are indicated (2, 3, 21, 31). Dotted lines are solely based on in vivo evidence. Membrane proteins are integrated into the cytoplasmic membrane (CM). See the text for details. sRNAs, small RNAs; cAMP, cyclic AMP.

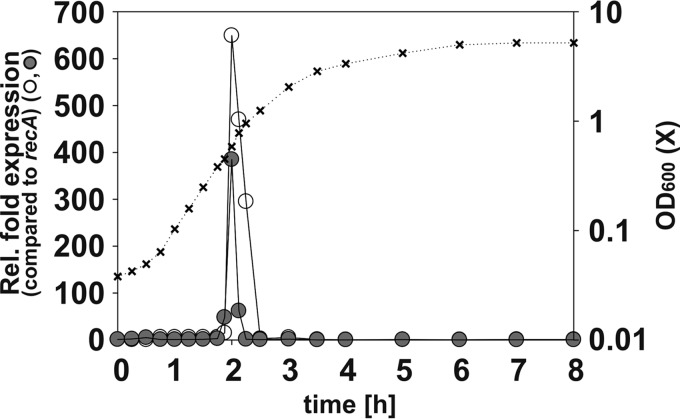

yjiY and yhjX are transiently induced at the onset of stationary phase.

The YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB systems are both known to be activated when E. coli is grown in an amino acid-rich milieu, such as LB medium. Furthermore, we had previously shown, using promoter luciferase activity assays, that expression of yjiY and yhjX begins at the onset of the transition into stationary phase (3). In this study, we quantitatively analyzed the levels of yjiY and yhjX mRNAs in a growing culture over time. For this purpose, E. coli strain MG1655 was shifted from noninducing conditions (minimal medium with glucose as the C source) into LB medium to follow the growth-dependent induction of these genes. At the indicated times, RNA was isolated, cDNA was synthesized, and the levels of the transcripts were determined by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1). Changes in mRNA levels relative to the level of the recA transcript were calculated using the CT method (13). yjiY and yhjX expression was first detected at an OD600 of 0.4 and reached a maximum at an OD600 of 0.6 (increase for yjiY, about 600-fold; increase for yhjX, about 400-fold). The mRNA levels subsequently dropped, and by the time the cell density had exceeded an OD600 of 1.2, transcripts were no longer detectable (Fig. 1). We analyzed mRNA levels into late stationary phase, but no additional induction was observed (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Transcriptional analysis of yhjX and yjiY, the target genes of YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB, respectively. Wild-type (MG1655) cells from a culture grown to stationary phase in M9 medium with glucose as the C source were transferred into fresh LB medium and cultured as described in Materials and Methods. Total RNA was isolated at various time points (crosses), and cDNA was synthesized. The levels of yjiY (open circles), yhjX (filled circles), and recA (as a reference) transcripts were determined by qRT-PCR for each time point. Changes in transcript levels (expressed relative [Rel.] to the level of recA expression) were calculated using the CT method. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and mean values are shown. Standard deviations were below 15%.

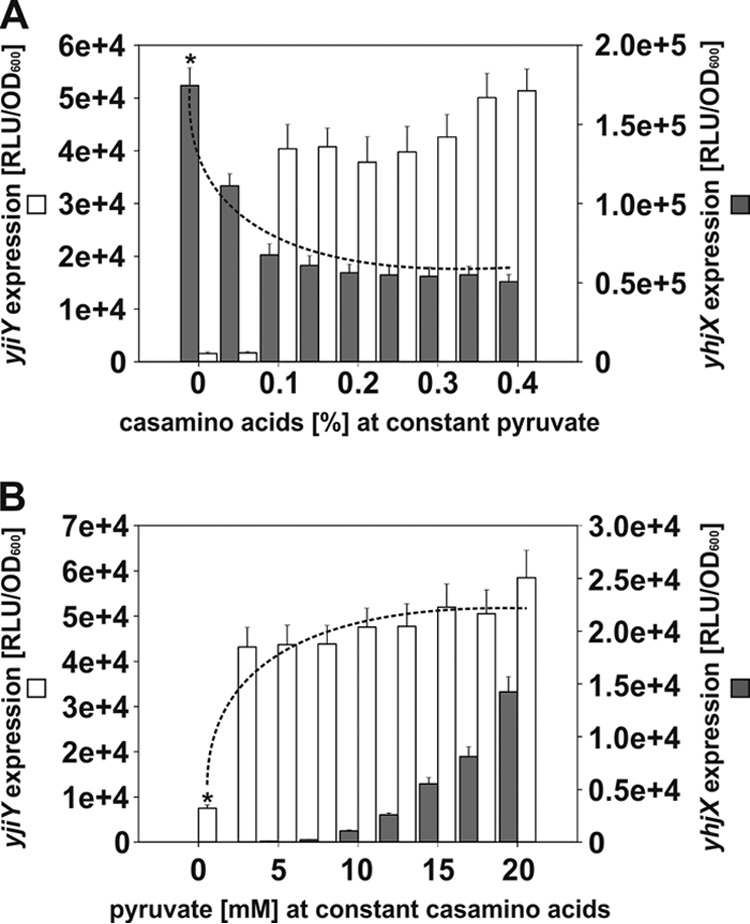

Stimulus-dependent crosswise alterations of yhjX and yjiY expression.

We have seen that both systems become active at the same time during growth of E. coli. Moreover, our previous studies had indicated that the two systems somehow behave in a coordinate fashion (2, 3). We therefore wanted to know how the stimulus-dependent activation of one system affects the expression of the target of the other. For this purpose, E. coli MG1655 was transformed with the reporter plasmids pBBR yjiY-lux and pBBR yhjX-lux. Cells were cultivated under aerobic conditions in M9 minimal medium, using as C sources succinate and either a constant level of pyruvate with increasing amino acid concentrations (Fig. 2A) or a constant level of amino acids and increasing pyruvate concentrations (Fig. 2B). The OD600s of all cultures were determined and showed no significant differences in overall growth rates. Luciferase activities were determined separately for the two reporter genes and normalized to the optical density (RLU/OD600).

FIG 2.

Stimulus-dependent crosswise alterations of yjiY and yhjX expression. E. coli MG1655/pBBR yjiY-lux and MG1655/pBBR yhjX-lux were cultivated in M9 medium containing succinate and various concentrations of Casamino Acids and pyruvate. The luciferase activities of the two reporter strains were measured after induction for 120 min. (A) Cells were cultivated under yhjX-inducing conditions in the constant presence of 20 mM pyruvate, and the influence of increasing concentrations of Casamino Acids on the expression of yhjX (filled bars) and yjiY (open bars) was monitored. (B) Cells were cultivated under yjiY-inducing conditions in the constant presence of 0.4% Casamino Acids, and the impact of increasing concentrations of pyruvate on expression of yjiY (open bars) and yhjX (filled bars) was assessed. Average values from three independent experiments are plotted, and error bars indicate standard deviations of the means. Asterisks, estimated maximal expression levels reached in the presence of a single stimulus; dotted lines, modulatory effect of the presence of the stimulus sensed by the other system.

YehU/YehT-mediated activation of yjiY is strongly dependent on amino acids (Fig. 2A and B) (10,000-fold induction) and was boosted 5- to 6-fold by the addition of pyruvate, irrespective of the concentration used (Fig. 2B). In contrast, yhjX expression was significantly downregulated in the presence of amino acids (2.6-fold) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, much higher concentrations of pyruvate were needed to induce yhjX expression when the medium contained amino acids (Fig. 2B). Whereas in the absence of amino acids the threshold pyruvate concentration was determined to be 600 μM (3), addition of amino acids to the medium raised this threshold value to 10 mM (Fig. 2B). These results not only reveal cross talk between the two systems but also show that they have opposite effects on each other. Activating conditions for YehU/YehT have a negative effect on the activation of the YpdA/YpdB system, whereas activating conditions for YpdA/YdpB boost activation of the YehU/YehT system.

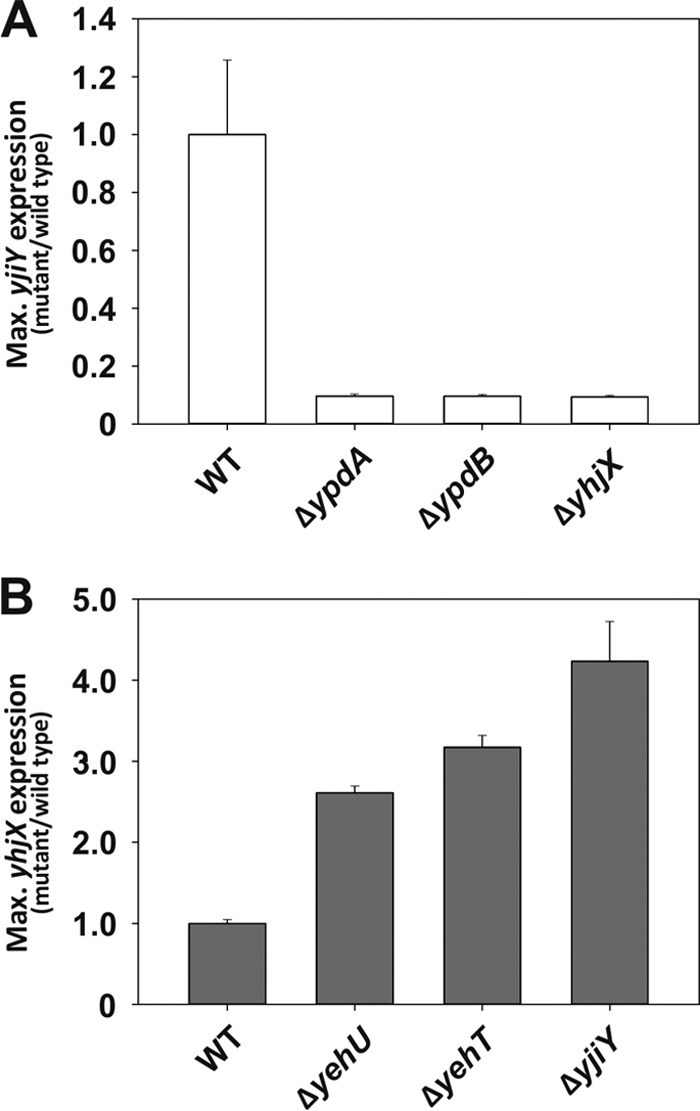

Expression of yjiY and yhjX in various deletion mutants.

To corroborate these cross-talk effects, we systematically analyzed the effect of deletion of individual signaling components or their target genes on yjiY and yhjX expression. The mutants were cultivated under activating conditions, i.e., in amino acid-containing medium in the case of the yjiY reporter strains (Fig. 3A) and pyruvate-containing medium in the case of the yhjX reporter strains (Fig. 3B). The two mutant strains for the YpdA/YpdB signaling cascade (the ΔypdA and ΔypdB mutants), as well as the transporter-negative mutant (the ΔyhjX mutant), displayed significantly reduced yjiY promoter activity compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 3A). In contrast, in mutants lacking the YehU/YehT signaling cascade or the YjiY transporter, yhjX promoter activity was significantly increased (the increases were 2.6-fold for the ΔyehU mutant, 3.2-fold for the ΔyehT mutant, and 4.2-fold for the ΔyjiY mutant) relative to that for the wild type (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results confirm that activation of the YehU/YehT signaling cascade, which results in YjiY production, suppresses YpdA/YpdB-mediated yhjX induction, whereas activation of the YpdA/YpdB signaling cascade, as well as inducing the synthesis of YhjX, promotes expression of yjiY. These observations are in agreement with the transcriptome data, which had indicated that overproduction of one response regulator and subsequent expression of the corresponding target gene were sufficient to alter the output of the other two-component system (2, 3). However, the observation that, in each case, deletion of the transporter has the same effect as the elimination of either of the signaling components is unexpected, as it implies that the transporters themselves exert feedback effects on the signaling systems.

FIG 3.

Influence of deletions in the signal transduction relay or target transporter of one LytS/LytTR two-component system on the expression of target genes of the other. Maximal (Max.) luciferase activities (RLU/OD600) were determined for yjiY (open bars) (A) and yhjX (filled bars) (B) under inducing conditions (0.4% Casamino Acids for yjiY and 20 mM pyruvate for yhjX) for each mutant and expressed relative to the values for wild-type (WT) E. coli MG1655 (normalized to 1.0). Experiments were performed at least three times, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means.

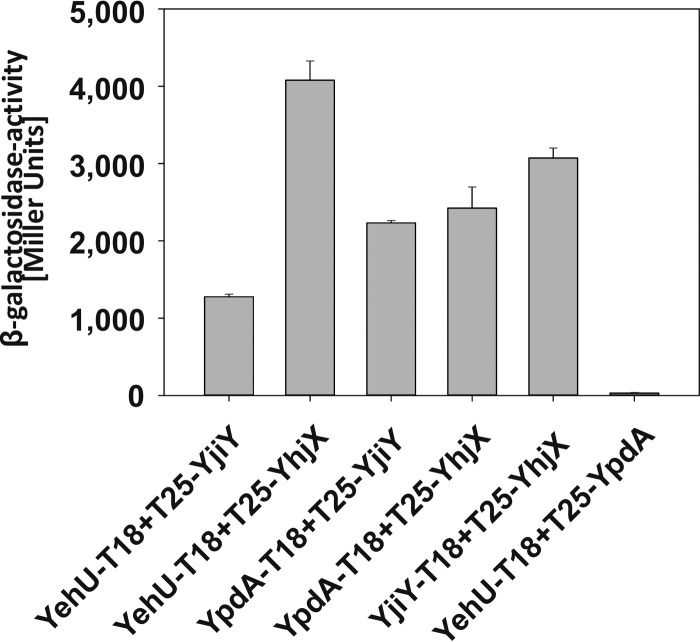

Detection of protein-protein interactions between histidine kinases and transporters.

The confirmation of cross talk between the two signaling systems and their target proteins described above focused our attention on its physical basis. To uncover possible interactions between the proteins of interest, we screened all combinations of the membrane-integrated components using the bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid system. All possible N- and C-terminal CyaA-hybrid constructs were generated and tested in all possible combinations. We used the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast leucine zipper fusion constructs zip-T18 and T25-zip (14) as positive controls (3,000 Miller units) (data not shown). We found a strong interaction between the HK YehU and both transporters, YjiY and YhjX (Fig. 4). The HK YpdA likewise interacted strongly with both transporters (Fig. 4). LysP fusion constructs (LysP is a lysine-specific secondary transporter) were used as negative controls (15), and these showed no interaction with either HKs or transporters (<250 Miller units). Moreover, we found that the transporters could form YjiY-YhjX hetero-oligomers, but none of the tested combinations indicated an interaction between YehU and YpdA (Fig. 4). In addition, all four proteins were observed to be capable of homo-oligomerization (data not shown).

FIG 4.

A two-hybrid assay based on fragmented bacterial adenylate cyclase (Cya) was used to identify protein-protein interactions in vivo. For this purpose, fragments T18 and T25 of Bordetella pertussis CyaA were fused to the proteins of interest, as indicated, while fusions to yeast leucine zipper fragments were used as a positive control (3,000 Miller units). E. coli BTH101 was cotransformed with plasmid pairs encoding the N-terminal T18 and C-terminal T25 hybrids. Cells were grown under aerobic conditions in LB medium supplemented with 0.5 mM IPTG at 30°C overnight. The activity of the reporter enzyme β-galactosidase was determined and served as a measure of the interaction strength (16). The experiment was performed in triplicate, and error bars indicate standard deviations of the means.

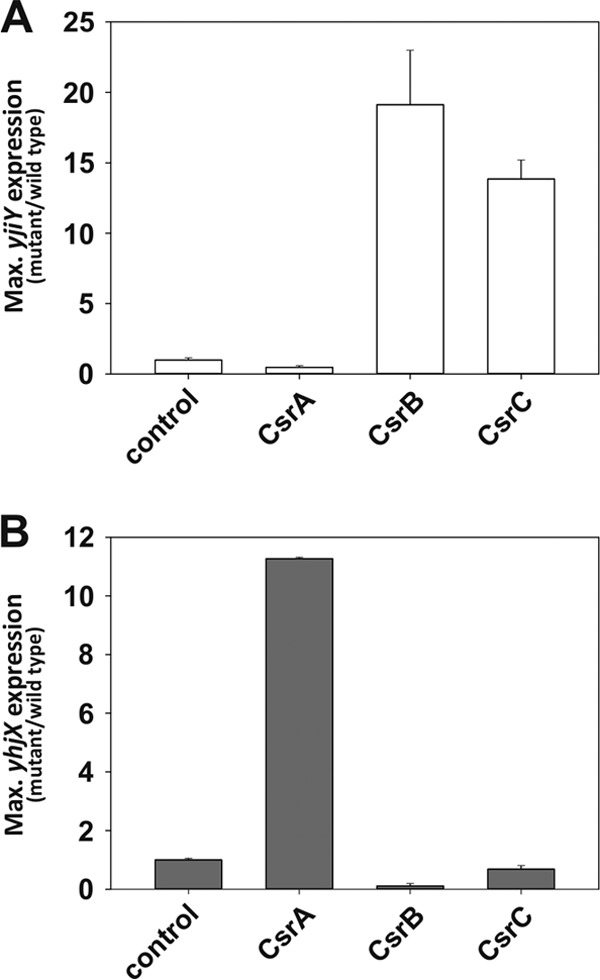

Influence of CsrA on yjiY and yhjX expression.

Carbon storage regulator A (CsrA) is an RNA-binding protein that regulates gene expression posttranscriptionally by modulating ribosome binding and/or mRNA stability (17). Members of the CsrB family of noncoding regulatory RNA molecules (CsrB and CsrC in E. coli) contain multiple CsrA-binding sites and function as antagonists by sequestering the protein (17). Depending on the particular organism, the Csr system participates in global regulatory circuits that control central carbon flux, the production of extracellular compounds, cell motility, biofilm formation, quorum sensing, and/or pathogenesis (18).

Synthesis of CstA, a putative peptide transporter (19) which shares a high degree of sequence identity (62%) and similarity (76%) with the target product of the YehU/YehT system, YjiY, is subject to CsrA regulation (20). Therefore, we searched the 5′ untranslated leader region (5′ UTR) of both the yhjX and yjiY mRNAs for CsrA-binding sites. In comparison to the previously described CsrA-binding site (21), the 5′ UTRs of yhjX and yjiY, respectively, contain one and two core motifs of the CsrA-binding site (20).

To gain insight into the impact of the Csr system on yhjX and yjiY, luciferase-based translational fusions (plasmids pBBR yjiY′-lux and pBBR yhjX′-lux) were constructed. Expression of yhjX and yjiY upon overproduction of CsrA, CsrB, and CsrC and in comparison to that for a negative control (empty vector) was analyzed. Overproduction of CsrB and CsrC caused an increase in yjiY expression (19-fold and 14-fold, respectively), whereas overproduction of CsrA led to a 2-fold decrease (Fig. 5A). Accordingly, deletion of csrA resulted in the constitutive expression of yjiY (data not shown). In contrast, expression of yhjX was increased 11-fold when CsrA was overproduced (Fig. 5B). Overproduction of CsrB and CsrC (1.5-fold) significantly reduced yhjX expression (9-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively). The deletion of csrA completely prevented yhjX expression (data not shown). These data thus indicate the participation of the Csr system as an additional checkpoint in the expression of yjiY and/or yhjX.

FIG 5.

CsrA influences the expression of yjiY and yhjX. A luciferase-based reporter assay was used to determine the pattern of yjiY (A) and yhjX (B) expression. Bacteria were cultivated under aerobic conditions, and the growth and activity of the reporter enzyme luciferase were monitored continuously. E. coli LMG194 was cotransformed with pBBR yjiY′-lux (open bars) or pBBR yhjX′-lux (filled bars), encoding translational fusions, and pBAD24-CsrA, pBAD24-CsrB, pBAD24-CsrC, or pBAD24 (control). Cells were grown in LB medium supplemented with l-arabinose (0.2% [wt/vol]). The maximal luciferase activity (RLU/OD600) was used as a measure of the degree of expression of yjiY or yhjX. All experiments were performed at least three times, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means.

DISCUSSION

YehU/YehT and YpdA/YpdB, two of the 30 histidine kinase/response regulator pairs in Escherichia coli K-12, belong to the LytS/LytTR family (22). Both systems are widespread among proteobacteria and show a high degree of conservation in gammaproteobacteria (5). The YehU/YehT system is activated upon growth of E. coli in medium containing peptides/amino acids as the C source. The YpdA/YpdB system has been shown to respond to extracellular pyruvate. In cells cultured in LB medium, which leads to the short-term release of pyruvate (3), both systems are activated, and expression of the corresponding target genes was found to occur at the same time as the onset of the stationary phase (Fig. 1). These results underline the importance of growth phase-dependent regulation of yjiY and yhjX expression as well as the interconnectedness of the two signaling systems. It appears that alterations in growth conditions due to a shortage of certain C sources may influence E. coli selectivity among the remaining nutrients. This might explain why signaling occurs in a single pulse sufficient to induce the expression of the two transporters YjiY and YhjX.

By growing E. coli in medium that had a more defined carbon source composition, we found that external pyruvate not only activates the YpdA/YpdB system but also promotes YehU/YehT-mediated induction of yjiY. In contrast, peptide/amino acid-dependent activation of YehU/YehT downregulates YpdA/YpdB-mediated yhjX expression. Remarkably, the phenotypes of mutants lacking the corresponding transporter perfectly mimicked these phenotypes. On the basis of these results, it appears that the cross-regulatory effects may be attributable to the respective transporters (Fig. 6). If this hypothesis is true, then regulation might take place either at the protein level (15) or at the level of the transported low-molecular-weight substrates (23). In this regard, it is important to note that in vivo protein-protein interaction studies revealed that each HK can interact with both transporters. Moreover, although each HK can form homo-oligomers, the two HKs do not show hetero-oligomerization. These findings are in agreement with the results of an unbiased screen for interacting HKs, in which YehU and YdpA were not among the interacting pairs (24). Interactions between sensory proteins and transporters, the so-called trigger transporter mechanism, have already been described (25). Well-characterized examples include the bacitracin resistance module BceS/BceAB in Bacillus subtilis (26) and the cosensory systems DctA/DcuS (27) and CadC/LysP in E. coli (15).

Furthermore, the domain architecture of YehU or YpdA, with at least five transmembrane helices and no obvious periplasmic ligand-binding domain, supports the idea of cosensory functions for YjiY and YhjX. However, detailed biochemical analyses will be required to obtain proof for it. Moreover, it is unclear whether YjiY and YhjX are, like LacY, constitutively produced at a very low copy number and involved in inducer uptake (28). A slight hint into this direction was provided in the crosswise regulatory experiment (Fig. 2): a low level of Casamino Acids (0.05%) that did not activate yjiY expression was sufficient to significantly downregulate yhjX expression (Fig. 2A), and vice versa, and at low pyruvate concentrations, yhjX was repressed but yjiY was already upregulated (Fig. 2B).

The interconnected response of the two signaling systems seems to be important for nutrient selection at a stage in the growth phase when C sources become limiting. Peptides and amino acids provide E. coli metabolism with sufficient amounts of pyruvate from alanine, glycine, or cysteine degradation. Under these conditions, any additional response to pyruvate would seem to offer E. coli no further benefit, and, therefore, yhjX expression is reduced. In contrast, an abundance of pyruvate, which results in strong yhjX expression, might lead to depletion of certain vital precursors, e.g., for the tricarboxylic acid cycle, or might affect the C/N ratio. In such a situation, it would be advantageous to concurrently activate YehU/YehT-mediated expression of yjiY, which codes for a putative peptide transporter, as uptake of peptides or amino acids could circumvent this limitation. Other examples of the coordinated regulation of metabolic pathways are known. For example, the expression of E. coli formate dehydrogenase operons (fdnGHI and fdhF) varies depending upon the relative abundance of nitrate, nitrite, and formate (29). The regulatory proteins NarL and NarP mediate complementary expression of these two operons depending on the nitrate concentration. It was suggested that such a dual adjustment is necessary for cells to quickly respond to environmental changes in levels of nitrate and formate (29). Hence, E. coli LytS/LytTR systems could participate in maintaining an optimal cellular carbon supply in preparation for nutrient limitation.

We have previously shown that yjiY expression is also dependent on cyclic AMP/cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) regulation (2) (Fig. 6). Here we found that CsrA also affects expression of yjiY and yhjX. CsrA is regulated via sequestration by the Hfq-dependent small RNAs CsrB and CsrC (18) (Fig. 6). We observed CsrA-mediated downregulation of yjiY and upregulation of yhjX expression (Fig. 6). Such dual regulation by CsrA is already known, as it positively influences enzymes of glycolysis while exerting a negative effect on glycogen biosynthesis and gluconeogenesis (30). Furthermore, degradation of yjiY and yhjX transcripts is not only under the control of CsrA, but it is also dependent on the interplay between ribosomal protein L4 and RNase E (31). RNase E has been shown to bind and degrade yjiY and yhjX transcripts, but when L4 interacts with the catalytic domain of RNase E, the enzyme activity is restrained, which results in increased yjiY and yhjX transcript levels (31). These data thus indicate the existence of further checkpoints at the posttranscriptional level before YjiY and YhjX are produced.

In conclusion, we have identified a novel nutrient-sensing regulatory network in E. coli composed of two histidine kinase/response regulator systems and two transporters. We propose that this unusual linkage is necessary to coordinate nutrient scavenging and the readjustment of bacterial metabolism in preparation for the stationary phase (32).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Exc114/2).

We thank Ingrid Weitl for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Heermann R, Jung K. 2010. Stimulus perception and signaling in histidine kinases, p 135–161 In Krämer R, Jung K. (ed), Bacterial signaling. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraxenberger T, Fried L, Behr S, Jung K. 2012. First insights into the unexplored two-component system YehU/YehT in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 194:4272–4284. 10.1128/JB.00409-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried L, Behr S, Jung K. 2013. Identification of a target gene and activating stimulus for the YpdA/YpdB histidine kinase/response regulator system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 195:807–815. 10.1128/JB.02051-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anantharaman V, Aravind L. 2003. Application of comparative genomics in the identification and analysis of novel families of membrane-associated receptors in bacteria. BMC Genomics 4:34. 10.1186/1471-2164-4-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C. 2013. STRING v9. 1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D808–D815. 10.1093/nar/gks1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galperin MY. 2008. Telling bacteria: do not LytTR. Structure 16:657–659. 10.1016/j.str.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cann M. 2007. Sodium regulation of GAF domain function. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35:1032–1034. 10.1042/BST0351032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoraghi R, Corbin JD, Francis SH. 2004. Properties and functions of GAF domains in cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and other proteins. Mol. Pharmacol. 65:267–278. 10.1124/mol.65.2.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. 2009. Structure and signaling mechanism of Per-ARNT-Sim domains. Structure 17:1282–1294. 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikolskaya AN, Galperin MY. 2002. A novel type of conserved DNA-binding domain in the transcriptional regulators of the AlgR/AgrA/LytR family. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2453–2459. 10.1093/nar/30.11.2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heermann R, Zeppenfeld T, Jung K. 2008. Simple generation of site-directed point mutations in the Escherichia coli chromosome using Red®/ET® recombination. Microb. Cell Fact. 7:14. 10.1186/1475-2859-7-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aiba H, Adhya S, de Crombrugghe B. 1981. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 256:11905–11910 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3:1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karimova G, Ladant D. 2005. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a cyclic AMP signaling cascade, p 499–515 In Golemis E. (ed), Protein-protein interactions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauschmeier M, Schüppel V, Tetsch L, Jung K. 2014. New insights into the interplay between the lysine transporter LysP and the pH sensor CadC in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 426:215–229. 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller JH. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria, 4th ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2007. CsrB sRNA family: sequestration of RNA-binding regulatory proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:156–163. 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romeo T, Vakulskas CA, Babitzke P. 2013. Post-transcriptional regulation on a global scale: form and function of Csr/Rsm systems. Environ. Microbiol. 15:313–324. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02794.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultz JE, Matin A. 1991. Molecular and functional characterization of a carbon starvation gene of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 218:129–140. 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90879-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubey AK, Baker CS, Suzuki K, Jones AD, Pandit P, Romeo T, Babitzke P. 2003. CsrA regulates translation of the Escherichia coli carbon starvation gene, cstA, by blocking ribosome access to the cstA transcript. J. Bacteriol. 185:4450–4460. 10.1128/JB.185.15.4450-4460.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards AN, Patterson-Fortin LM, Vakulskas CA, Mercante JW, Potrykus K, Vinella D, Camacho MI, Fields JA, Thompson SA, Georgellis D, Cashel M, Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2011. Circuitry linking the Csr and stringent response global regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1561–1580. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07663.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulrich LE, Zhulin IB. 2010. The MiST2 database: a comprehensive genomics resource on microbial signal transduction. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:D401–D407. 10.1093/nar/gkp940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson C, Zhan H, Swint-Kruse L, Matthews K. 2007. The lactose repressor system: paradigms for regulation, allosteric behavior and protein folding. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64:3–16. 10.1007/s00018-006-6296-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sommer E. 2012. In vivo study of the two-component signaling network in Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis Ruperto-Carola University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tetsch L, Jung K. 2009. How are signals transduced across the cytoplasmic membrane? Transport proteins as transmitter of information. Amino Acids 37:467–477. 10.1007/s00726-009-0235-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dintner S, Staroń A, Berchtold E, Petri T, Mascher T, Gebhard S. 2011. Coevolution of ABC transporters and two-component regulatory systems as resistance modules against antimicrobial peptides in Firmicutes bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 193:3851–3862. 10.1128/JB.05175-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witan J, Bauer J, Wittig I, Steinmetz PA, Erker W, Unden G. 2012. Interaction of the Escherichia coli transporter DctA with the sensor kinase DcuS: presence of functional DctA/DcuS sensor units. Mol. Microbiol. 85:846–861. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buttin G, Cohen G, Monod J, Rickenberg H. 1956. Galactoside-permease of Escherichia coli. Ann. Inst. Pasteur 91:829–857 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Gunsalus RP. 2003. Coordinate regulation of the Escherichia coli formate dehydrogenase fdnGHI and fdhF genes in response to nitrate, nitrite, and formate: roles for NarL and NarP. J. Bacteriol. 185:5076–5085. 10.1128/JB.185.17.5076-5085.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabnis NA, Yang H, Romeo T. 1995. Pleiotropic regulation of central carbohydrate metabolism in Escherichia coli via the gene csrA. J. Biol. Chem. 270:29096–29104. 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh D, Chang SJ, Lin PH, Averina OV, Kaberdin VR, Lin-Chao S. 2009. Regulation of ribonuclease E activity by the L4 ribosomal protein of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:864–869. 10.1073/pnas.0810205106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson CN, Mandel MJ, Silhavy TJ. 2005. Escherichia coli starvation diets: essential nutrients weigh in distinctly. J. Bacteriol. 187:7549–7553. 10.1128/JB.187.22.7549-7553.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blattner FR, Plunkett G, III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1462. 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Studier FW, Moffatt BA. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189:113–130. 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. 1998. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:5752–5756. 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meselson M, Yuan R. 1968. DNA restriction enzyme from E. coli. Nature 217:1110–1114. 10.1038/2171110a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Godeke J, Heun M, Bubendorfer S, Paul K, Thormann KM. 2011. Roles of two Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 extracellular endonucleases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:5342–5351. 10.1128/AEM.00643-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guzman L, Belin D, Carson M, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]