Abstract

In Escherichia coli, aromatic compound biosynthesis is the process that has shown the greatest sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide stress. This pathway has long been recognized to be sensitive to superoxide as well, but the molecular target was unknown. Feeding experiments indicated that the bottleneck lies early in the pathway, and the suppressive effects of fur mutations and manganese supplementation suggested the involvement of a metalloprotein. The 3-deoxy-d-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (DAHP synthase) activity catalyzes the first step in the pathway, and it is provided by three isozymes known to rely upon a divalent metal. This activity progressively declined when cells were stressed with either oxidant. The purified enzyme was activated more strongly by ferrous iron than by other metals, and only this metalloform could be inactivated by hydrogen peroxide or superoxide. We infer that iron is the prosthetic metal in vivo. Both oxidants displace the iron atom from the enzyme. In peroxide-stressed cells, the enzyme accumulated as an apoprotein, potentially with an oxidized cysteine residue. In superoxide-stressed cells, the enzyme acquired a nonactivating zinc ion in its active site, an apparent consequence of the repeated ejection of iron. Manganese supplementation protected the activity in both cases, which matches the ability of manganese to metallate the enzyme and to provide substantial oxidant-resistant activity. DAHP synthase thus belongs to a family of mononuclear iron-containing enzymes that are disabled by oxidative stress. To date, all the intracellular injuries caused by physiological doses of these reactive oxygen species have arisen from the oxidation of reduced iron centers.

INTRODUCTION

Loew discovered catalase by chance while studying tobacco exudates in 1900 (1); McCord and Fridovich discovered superoxide dismutase as a contaminant of cytochrome c preparations in 1969 (2). In neither case was the raison d'etre of these enzymes known, although the investigators logically inferred that reactive oxygen species must be by-products of aerobic metabolism that, if not scavenged, would be toxic. Subsequent work confirmed that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide (O2−) are continuously generated in aerobic cells because redox enzymes accidently transfer electrons to molecular oxygen (3).

Exogenous hydrogen peroxide was shown to create DNA lesions, albeit at a rate that was only modestly mutagenic and usually nonlethal (4). This damage results from the Fenton reaction, in which electron transfer from ferrous iron to H2O2 generates the toxic hydroxyl radical, which in turn attacks nearby biomolecules, including DNA. Hydrogen peroxide is more effective at blocking growth, with low-micromolar doses being bacteriostatic, but the underlying injury was not obvious. While exogenous H2O2 can oxidize protein cysteine and methionine residues, the rate constants are typically so low that millimolar concentrations are required to cause a significant enzymatic deficit (5).

The postulated toxicity of O2− was controversial for quite a while. Although O2− is a radical, its oxidizing force is held in check by its anionic status, which inhibits its approach to electron-rich biomolecules. Early in vitro trials did not identify any biomolecules that it could damage (6–9). Then in 1986 Carlioz and Touati generated Escherichia coli mutants that lacked cytoplasmic superoxide dismutase (SOD) (10). These mutants exhibited several clear catabolic and biosynthetic defects: they were unable to use tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle substrates as primary carbon sources, and they could not grow unless the cultures were supplemented with branched-chain, aromatic, and sulfur-containing amino acids. The TCA cycle and branched-chain amino acid defects were subsequently shown to result from the ability of O2− to damage a family of iron-sulfur cluster-containing dehydratases (11–15). These enzymes include aconitase and fumarase of the TCA cycle and isopropylmalate isomerase and dihydroxyacid dehydratase of the branched-chain amino acid pathway. Such dehydratases use their solvent-exposed clusters to coordinate and activate substrates. Superoxide poisons those enzymes by directly complexing and then oxidizing the cationic cluster. In its oxidized form, the cluster is unstable, iron dissociates, and activity is lost.

Complementary experiments seeking H2O2 targets were then performed by creating E. coli mutants that lack its H2O2 scavengers: NADH peroxidase (also called alkylhydroperoxide reductase, encoded by ahpCF) and catalases G and E (encoded by katG and katE) (16). These triple (Hpx−) mutants grow well anaerobically. When they are inoculated into aerobic medium, they gradually accumulate up to ∼1 μM H2O2. This dose slightly exceeds the dose that activates the OxyR stress response to H2O2 (17, 18), and thus, it is likely to be within the range that E. coli occasionally encounters in nature. Notably, the Hpx− mutants, like SOD mutants, proved unable to grow in aerobic minimal medium without supplementation with aromatic amino acids (10, 19). As in the case of SOD mutants, the basis of the aromatic defect was unknown.

If aromatic amino acids are supplied, the nonscavenging mutants can grow. The exogenous addition of a higher dose of H2O2 again arrests growth, unless branched-chain amino acids are provided. This defect was tracked to oxidation by H2O2 of the isopropylmalate isomerase [4Fe-4S] cluster (19). Since this enzyme belongs to the same family of [4Fe-4S] dehydratases that O2− damages, other members of the family were tested. All were rapidly damaged by H2O2. Thus, this group of enzymes is a primary target of both oxidants.

The Hpx− mutants were subsequently shown to be additionally defective in the pentose phosphate pathway, due to inhibition of ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase (20). This nonredox enzyme employs a single ferrous iron atom, to which substrate binds during the catalytic reaction. Hydrogen peroxide can oxidize the iron atom, triggering its dissociation from the polypeptide and the consequent loss of activity. Several other mononuclear iron-containing enzymes were subsequently found to be similarly affected (21). Further, O2− was then shown to exert a similar effect (22).

Thus, several of the phenotypes of oxidative stress result from the ability of H2O2 and O2− to oxidize the exposed iron cofactors of metabolic enzymes. To learn whether this represents the full range of oxidative toxicity, it is necessary to identify the causes of other growth defects. In this study, we sought the basis of the aromatic auxotrophy of stressed cells. We found that both H2O2 and O2− disable the first enzyme in the aromatic biosynthetic pathway, and we demonstrated that this is a mononuclear iron-containing enzyme. This injury constitutes the growth-limiting target in H2O2-stressed cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Amino acids, antibiotics, catalase (from bovine liver), catechol, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), EDTA, d-erythrose 4-phosphate sodium salt, phospho(enol)pyruvic acid tri(cyclohexylammonium) salt, ferrous ammonium sulfate hexahydrate, horseradish peroxidase (HRP), imidazole, manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate, zinc chloride, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG), d-penicillamine, trichloroacetic acid, sodium (meta)periodate, sodium arsenite, thiobarbituric acid, cyclohexanone, xanthine, xanthine oxidase, catalase, and 30% H2O2 were from Sigma. Tris-HCl was purchased from Fisher. Amplex ultrared was from Life Technologies. d-Erythrose 4-phosphate sodium salt was obtained from Sigma, Omicron Biochemicals, and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Tris-HCl was from Fisher.

Bacterial growth.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium contained 10 g tryptone, 10 g NaCl, and 5 g yeast extract per liter. Minimal medium was composed of minimal A salts (23) supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.5 μg/ml thiamine, and 0.5 mM histidine. Other amino acids were added at 0.5 mM where indicated.

Anoxic growth was carried out in a Coy anaerobic chamber, which contained an atmosphere consisting of 85% nitrogen, 10% hydrogen, and 5% carbon dioxide. Cultures were maintained at 37°C. Aerobic cultures were aerated by vigorous shaking.

Strains and strain construction.

A comprehensive strain list is provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Constructions in the Hpx− background were carried out in an anaerobic chamber to ensure that no suppressor mutations were selected. Null mutations were constructed using the λ Red recombinase method (24). All mutations were then moved into the desired strain backgrounds by P1 transduction (23) and confirmed by PCR. Antibiotic cassettes were finally removed by transformation of pCP20, followed by removal of the plasmid (24).

Single-copy lacZ fusions to the aroF promoter were made by integration of the construct into the lambda attachment site; thus, the native aroF gene was retained on the chromosome (25, 26). The promoter region was amplified using the primers 5′-GCATCGCTGCAGTTCTTTCTCCTTTTTCAAAG-3′ and 5′-GCATCGGAATTCCATGATGGCGATCCTGTTTA-3′ with PstI and EcoRI restriction sites, respectively. This region begins 160 bases upstream of the transcriptional start site and extends for 211 bases up to and including the start codon. The modified CRIM (conditional-replication, integration, and modular) plasmid pSJ501, which contains a chloramphenicol resistance cassette, was used to allow anaerobic selections. The aroF promoter region was inserted into pSJ501 and confirmed by sequencing. The construct was then integrated into the chromosome and transduced into the desired recipient strains.

Growth curves.

Cells were first grown overnight to stationary phase in anoxic minimal medium containing glucose (minimal glucose medium). Cultures were then inoculated to ∼0.010 optical density (OD) and grown anaerobically to 0.200 OD. The cells were then used to inoculate fresh oxic minimal medium to 0.005 OD, and optical density was monitored at 600 nm.

H2O2 accumulation.

Cells were first grown overnight to stationary phase in anoxic minimal glucose medium. Cultures were then inoculated to ∼0.01 OD and grown anaerobically to 0.2 OD. The cells were then used to inoculate fresh oxic minimal glucose medium to 0.005 OD. Aliquots were removed periodically, cells were removed by filtration, and the filtrate was frozen on dry ice. After all samples were collected, H2O2 concentrations of the filtrates were measured by the Amplex red/horseradish peroxidase method (16). Fluorescence was measured using a Shimadzu RF Mini-150 fluorometer. Note that H2O2 quickly equilibrates across the cytoplasmic membranes of nonscavenging cells, so that measurements of extracellular H2O2 concentration indicate the intracellular concentration as well (17).

Purification of DAHP synthase.

3-Deoxy-d-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (DAHP synthase) was purified by cloning the open reading frame (ORF) of the E. coli aroG gene into the T7-containing pET42a vector, which fuses the inserted open reading frame with an N-terminal His tag. The aroG ORF was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CGACCTACCATGGGCAGCATCGAAGGTCGTATGAATTATCAGAACGACGATTTACGCATC-3′, which includes an NcoI restriction site, and the reverse primer 5′-GCTGGATGGATCCTTACCCGCGACGCGCTTTTACTGCATTC-3′, which includes a BamHI restriction site. After ligation, plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α and selected on LB plates containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin. A transformant found to have the correct aroG sequence was chosen for DAHP synthase purification. This plasmid was purified and transformed into E. coli strain BL21. This strain, containing plasmid pAroG-His, was grown to stationary phase in LB medium containing glucose (LB glucose medium) containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin, diluted to 0.006 OD into fresh LB glucose medium containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin, and grown to 0.200 OD at 37°C. This preculture was then used to inoculate to 0.005 OD 1 liter of fresh LB glucose medium containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin, and cells were grown at 37°C to 0.6 OD. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was then added to a final concentration of 0.4 mM, and the culture was shifted to 15°C and incubated for 18 h.

The purification of DAHP synthase was performed under oxic conditions as follows. The buffers used were sample buffer (50 mM KPi [pH 7.4], 0.5 M NaCl, 200 μM phosphoenolpyruvate [PEP], and 20 mM imidazole), elution buffer (50 mM KPi [pH 7.4], 0.5 M NaCl, 200 μM PEP, and 0.5 M imidazole), cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 M NaCl, 200 μM PEP, and 5 mM CaCl2), and storage buffer (50 mM KPi [pH 6.4], 200 μM PEP, and 1 mM EDTA). Cells were centrifuged and washed with 30 ml ice-cold sample buffer, resuspended in 20 ml ice-cold sample buffer, and sonicated. Cell extracts were cleared by centrifugation for 15 min at 4,000 × g at 4°C. Two His Gravitrap prepacked columns (GE Healthcare) were equilibrated aerobically at 4°C using 10 ml sample buffer. Each column was loaded with 5 ml cleared extract and washed with 10 ml sample buffer. Elution was conducted by adding 3 ml elution buffer to each column. This step was repeated to ensure all protein had been eluted from the column. The eluates were pooled, and 3 ml was dialyzed against 3 liters cleavage buffer at 4°C for 8 h.

To remove the 10-His tag, dialysate was cleaved using a Novagen factor Xa cleavage/capture kit. The cleavage mixture contained 10 μl factor Xa (2 U/μl) and 990 μl dialysate per ml. This mixture was incubated at 4°C for 72 h. Factor Xa was then removed according to the kit instructions. Flowthrough from multiple columns was pooled. Next, to remove uncleaved AroG with the His10 tag (AroG-His10), a His Gravitrap column was equilibrated with 10 ml sample buffer at 4°C. Flowthrough from factor Xa removal was then loaded onto the column and washed with 5 ml sample buffer. The resulting purified DAHP synthase was dialyzed against a 1,000-fold excess of storage buffer for 8 h at 4°C and stored on ice. Pure DAHP synthase obtained was 0.48 mg/ml and at least 90% pure as determined by SDS-PAGE. Due to metal chelation by storage buffer, the purified protein was recovered in the inactive apoprotein form.

Continuous assay of purified DAHP synthase.

Purified DAHP synthase was assayed as described previously (27). The purified enzyme was diluted 4-fold, thus reducing EDTA levels to 0.25 mM, and treated with 50 μM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and 0.75 mM each metal in 0.1 M KPi (pH 6.4) under anoxic conditions for 10 min at ambient temperature. This mixture was then diluted 1:20 into a 0.5-ml reaction mixture containing saturating amounts of PEP and erythrose 4-phosphate with or without 100 μM H2O2. This sample was assayed by measuring the disappearance of the PEP signal at 232 nm over a period of at least 30 min. The extinction coefficient for PEP is 2.84 mM−1 cm−1. The specific activity obtained from Fe-metallated DAHP synthase was approximately 2.4 ΔA/min/mg of protein (A stands for absorbance).

DAHP synthase assays. (i) In vivo H2O2 or O2− exposure.

Cells for assays were grown in minimal medium without aromatic amino acids to ensure good expression of DAHP synthase. Samples of aerated cells were collected by centrifugation of 50-ml culture for 10 min at 6,000 × g at 4°C in a bench-top centrifuge, and pellets were transferred into the anaerobic chamber; all subsequent steps were performed under anoxic conditions. The supernatants were discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in 25 ml cold 0.1 M KPi, pH 6.4. The samples were spun again for 10 min at 6,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatants were again discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in 1 ml cold anoxic 0.1 M KPi, pH 6.4, containing 9 mM PEP and 100 μM DTPA. The PEP stabilizes extant metal centers, while DTPA prevents the postlysis metallation of apoprotein. The samples were then lysed by sonication for 1 min using 3-s pulses. The extracts were then spun for 1 min at 20,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatants were then assayed immediately.

The assay of DAHP synthase activity uses periodate treatment to generate a cleavage product of DAHP. This product is then visualized by formation of a chromophore upon the addition of thiobarbituric acid. The method described below is a variation of the method of Weissbach and Hurwitz (28) and modified by Doy and Brown (29).

(ii) Part I of the DAHP synthase activity assay.

In part I of the assay of DAHP synthase activity, anoxic tubes were prepared containing 0.1 M KPi (pH 6.4), 0.75 mM PEP, and 0.6 mM erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P), unless otherwise indicated, and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Treated extracts were added to a final volume of 500 μl in order to start the reaction. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 min, and then a 150-μl aliquot from the reaction mixture was pipetted directly into a 1.5-ml tube containing 50 μl ice-cold 10% tricarboxylic acid (TCA). Samples were kept on ice while the remaining samples were harvested, until the final sample had been on ice for 5 min. The samples were then centrifuged 10 min at 20,000 × g at 4°C to remove debris and removed from the anaerobic chamber.

(iii) Part II of the DAHP synthase activity assay.

In part II of the assay of DAHP synthase activity, 125 μl of each sample in TCA was pipetted into a glass test tube containing 125 μl of 25 mM periodate in 0.075 M H2SO4, and the mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Next, 250 μl of 2% arsenite in 0.5 M HCl was added to each sample. The samples were then shaken well for a few seconds by hand until the yellow color disappeared. Next, 1 ml of 0.6% thiobarbituric acid in 0.5 M Na2SO4 was added to each sample and mixed well by shaking by hand for a few seconds. The tubes were then capped, heated vigorously (slowly boiling in a 110°C heating block) for 15 min, and then placed in a water bath at room temperature for 5 min. One milliliter of cyclohexanone was added to a 15-ml glass centrifuge tube for each sample before 1 ml of each reaction mixture was added to the centrifuge tubes. The samples were mixed well by shaking gently back and forth for a few seconds, and then they were centrifuged at 1,000 × g at room temperature to separate layers. The absorbance of 500 μl of the top organic layer was measured at 549 nm using a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 25 spectrophotometer. The extinction coefficient for the chromogen is 8.0 × 10−4 M−1 cm−1. The activity of the enzyme in extracts from anaerobically grown wild-type cells was 0.24 ΔA/min/mg.

In vitro H2O2 exposure of cell extracts.

Cultures were grown anaerobically overnight in minimal glucose medium containing minimal A salts (minimal A glucose medium), subcultured anaerobically for Hpx− cells or aerobically for Kat− cells (16) in the same medium, and grown to 0.2 OD. Cells were harvested as described above, and anoxic extracts were prepared in 0.1 M KPi, pH 6.4, containing 9 mM PEP and 0.1 mM DTPA as described above. Samples were challenged anoxically in the presence or absence of 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min at ambient temperature before being added to the reaction mixture, as was done for in vivo exposure. The remainder of the assay was identical to in vivo exposure determinations of DAHP synthase activity.

In vitro H2O2 exposure of pure DAHP synthase.

Purified apo-DAHP synthase was diluted 3-fold into anaerobic 0.1 M KPi (pH 6.4) and metallated by the addition of 50 μM TCEP and 750 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 for 10 min at room temperature. Metallated DAHP synthase (50 μl) was then added to a continuous assay mixture with or without 100 μM H2O2 and assayed for activity by the continuous assay method.

In vitro reactivation of DAHP synthase.

Reactivation of DAHP synthase damaged in vivo or in vitro was carried out as described above, except that 100 μl extract was treated with 0.1 mM H2O2 for 5 min or 5 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM TCEP for 15 min. Where indicated, protein damaged in vivo was additionally exposed to 6 mM penicillamine for 20 min. Penicillamine-treated samples were then treated with either 5 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 or ZnCl2 prior to assay.

Inactivation rate determination.

Rates of inactivation of DAHP synthase by H2O2 were measured as for in vitro measurements, using Hpx− cells, except that the inactivation was carried out using 5, 20, or 100 μM H2O2 for 2 min before 10 μl of a 1:1,000 dilution of catalase was added, and the activity was determined. These measurements were done in triplicate at 4, 10, and 20°C.

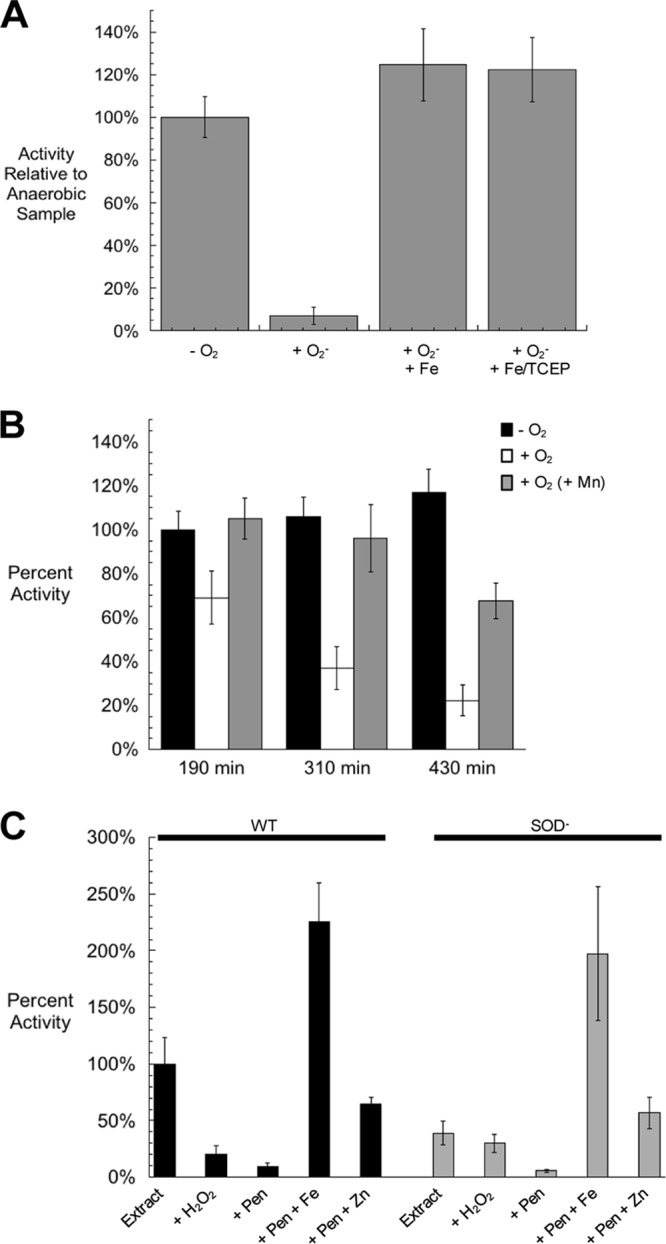

In vitro O2− exposure.

Purified DAHP synthase was diluted 1:3 into anaerobic 0.1 M KPi buffer (pH 6.4) and metallated for 10 min with 750 μM Fe(NH4)2(SO4) in the presence of 100 μM TCEP. O2− was generated in vitro by adding 70 μl of the Fe-metallated DAHP synthase to an aerobic mixture of 120 μl of 0.1 M KPi (pH 6.4), 10 μl of catalase diluted 1:200, 30 μl of 1 mM xanthine, and 10 μl xanthine oxidase; the mixture was then incubated aerobically for 3 min. To stop the O2− exposure, 10 μl of SOD (20,000 U/ml) was added; in control reactions, SOD was added in the same concentration prior to the addition of xanthine oxidase. The enzyme was then assayed as described above using 70 μl of the treated DAHP synthase mixture.

Determination of metal content.

Cells were grown overnight in the anaerobic chamber in minimal A glucose medium containing thiamine and 17 amino acids (Phe, Trp, and Tyr were omitted) to 0.2 OD. Cells were harvested as described above, and extracts were prepared anaerobically in 0.1 M KPi, pH 6.4, containing 9 mM PEP and 0.1 mM DTPA. Samples were assayed as described above except that either 3 μM or 180 μM erythrose 4-phosphate was used in the reaction. The remainder of the assay was identical to in vivo exposure determinations of DAHP synthase activity. The ratio of reaction rates at the two different concentrations of erythrose 4-phosphate was calculated for each of the three metals using published Km values for DAHP synthase (30).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Expression of aroF was monitored using a lacZ transcriptional fusion. Cells were grown anaerobically overnight in minimal A glucose medium, subcultured in 10 ml of the same medium anaerobically, and grown at 37°C to 0.15 OD. Cultures were then used to inoculate 30 ml of the same medium to either 0.040 OD (for Hpx− cells without supplements) or 0.010 OD (all others). The medium was prepared fresh aerobically, with or without 0.5 mM aromatic amino acids and with or without 50 mM Mn, as indicated. Cells were grown aerobically at 37°C for 4 h. The cell densities at harvesting were between 0.100 and 0.150 OD.

The cells were harvested by centrifuging 20-ml culture samples at 6,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatants were discarded, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 20 ml ice-cold 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0). The samples were centrifuged again for 10 min to wash the pellets, and the supernatants were discarded. The cell pellets were then resuspended in 2 ml of 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) and lysed by a French press. The samples were then spun for 20 min at 4°C at 12,000 × g to remove cell debris. The supernatants were then assayed for β-galactosidase activity.

Assays were run in 1.2-ml reaction volumes containing 0.2 ml of 4-mg/ml o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, 0, 20, 40, or 80 μl cell extract, and the balance of Z buffer. Reactions were started by the addition of the cell extract and monitored for 8 min at 420 nm.

Enterochelin assay.

Cultures were grown anaerobically overnight in minimal A glucose medium and subcultured anaerobically in the same medium. Cells were diluted to 0.005 OD in the same aerobic medium with or without aromatic amino acids or 19 amino acids as indicated at time zero, and cultures were incubated aerobically overnight at 37°C. Cells were removed by spinning 1.5-ml cultures for 10 min at 6,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was used to assay for catechol (31).

RESULTS

DAHP synthase is damaged by H2O2 in vivo.

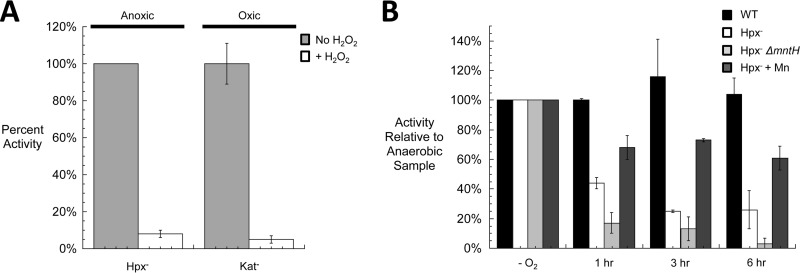

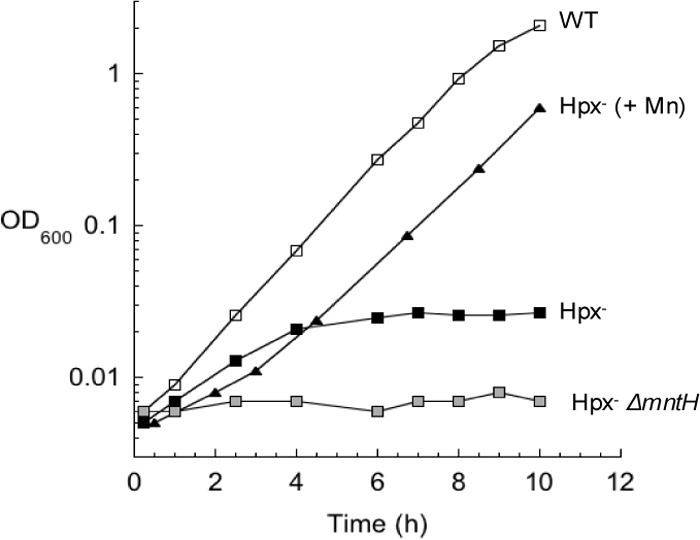

Hpx− (ahpCF katG katE) strains lack the ability to efficiently scavenge H2O2. When anaerobic cultures are aerated, the H2O2 that is formed as a by-product of metabolism rapidly equilibrates across the membrane and accumulates in the growth medium, gradually rising to about 1 μM (19). Under these conditions, the Hpx− strain could not grow unless aromatic amino acids were supplied exogenously (Fig. 1A). The growth defect became apparent by the time that 0.3 μM H2O2 had accumulated, making this the most H2O2-sensitive cell process yet known (Fig. 1B). As a point of comparison, ∼8 μM H2O2 is needed to disrupt the synthesis of branched-chain amino acids (19).

FIG 1.

Submicromolar intracellular H2O2 disrupts the initial stage of aromatic amino acid synthesis. (A) At time zero, wild-type (WT) and mutant cultures growing exponentially in anoxic medium containing glucose (glucose medium) were diluted into aerobic medium. Where indicated, three aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine) were added to the medium [(+ FWY)]. OD600, optical density at 600 nm. (B) Accumulation of H2O2 in the medium of Hpx− mutants. The H2O2 equilibrates across the membrane sufficiently quickly that the extracellular and intracellular H2O2 concentrations are effectively the same (17). Error bars represent the standard deviations from the means of three independent replicate cultures. (C) Cultures growing exponentially in anoxic glucose medium were diluted at time zero into aerobic medium. Where indicated, 50 μM shikimate (shik) was added to the medium.

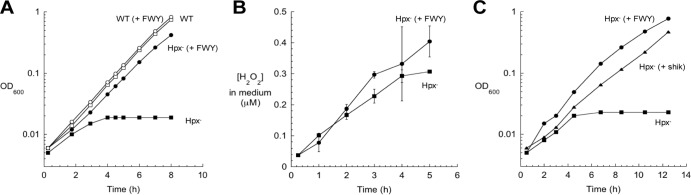

To restore growth, all three aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine) had to be added to the medium (data not shown). The most parsimonious explanation is that H2O2 poisons a part of the common pathway for aromatic biosynthesis. This pathway begins with the condensation of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P), progresses through a series of three additional reactions to shikimate, and then ends with three more steps to chorismate (Fig. 2). Chorismate is the end product that branches not only to the individual biosynthetic pathways for the three aromatic amino acids but also to those for folate, ubiquinone, menaquinone, and siderophores. In fact, assays demonstrated that Hpx− mutants secreted no siderophores, confirming that the block preceded chorismate (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Shikimate is a common pathway member that can be imported from growth medium (32), and when it was supplied, Hpx− cells were able to grow almost as quickly as when all three aromatic amino acids were provided (Fig. 1C). This indicated that the block in the pathway was upstream of shikimate.

FIG 2.

Enzymes and intermediates of the shikimate pathway. The solid black arrows represent reactions, dashed arrows represent multiple reactions, chemical intermediates are named, and enzymes are denoted in brackets next to the reactions that they catalyze. Abbreviations: PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; DAHP, 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate; DHQ, dehydroquinate; DHS, dehydroshikimate; Shikimate 3-P, Shikimate 3-phosphate; 5-EPS-3-P, 5-enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-phosphate; Trp, tryptophan; Tyr, tyrosine; Phe, phenylalanine.

The aromatic pathway contains no enzymes of the [4Fe-4S] dehydratase class that is known to be H2O2 sensitive (19). However, recent work has demonstrated that some iron-dependent mononuclear enzymes can also be inactivated by H2O2 (20, 21). These nonredox proteins use a single iron atom to bind and activate substrate; because the iron is solvent exposed, it can be contacted and oxidized by small oxidants. The first activity of the common biosynthetic pathway, 3-deoxy-d-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate (DAHP) synthase, is supplied by three isozymes, and each is cofactored by a divalent metal. The identity of this metal has been debated (30, 33–37); one possibility is ferrous iron, making it a plausible target of H2O2. Extracts were prepared from cells that were grown anaerobically and had thereby been shielded from oxidative stress. When these fresh extracts were exposed to H2O2 in vitro, the DAHP synthase was inactivated (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

DAHP synthase enzymes are inactivated by H2O2 in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cultures were grown exponentially to 0.2 OD in anoxic medium (Hpx− cells) or oxic medium (catalase-deficient cells). Extracts were prepared anoxically. Where indicated, extracts were exposed to 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min prior to the assay of DAHP synthase activity. (B) Cultures growing exponentially in anoxic medium were diluted at time zero into oxic medium. At various intervals (time shown in hours), aliquots were shifted to the anaerobic chamber, and extracts were prepared and assayed. Where indicated, 1 μM MnCl2 was added to the medium. For both panels, the error bars represent the standard deviations from the means of three independent experiments.

Control experiments were performed to determine which of the three isozymes of DAHP synthase contributed to the H2O2-sensitive activity. The three isozymes are each feedback inhibited by a different aromatic amino acid, and so the activity of each isozyme could be evaluated by supplying the two noninhibiting amino acids to the reaction mixture. Under the growth conditions that were used, 80 to 90% of the activity arose from Phe-sensitive AroG, 10 to 15% from Tyr-sensitive AroF, and <10% from Trp-sensitive AroH. Similar ratios have been reported by others (38). In vitro measurements indicated that the AroG and AroF isozymes were sensitive to H2O2 treatment and suggested that AroH is also (data not shown).

To appraise whether this sensitivity could explain the aromatic auxotrophy of Hpx− cells, DAHP synthase activity was tracked after aeration. The activity progressively diminished to a final level of only 20 to 25% of the wild-type activity on the same time frame as the appearance of the auxotrophy (Fig. 3B). This result confirmed that DAHP synthase is sensitive to H2O2 in vivo.

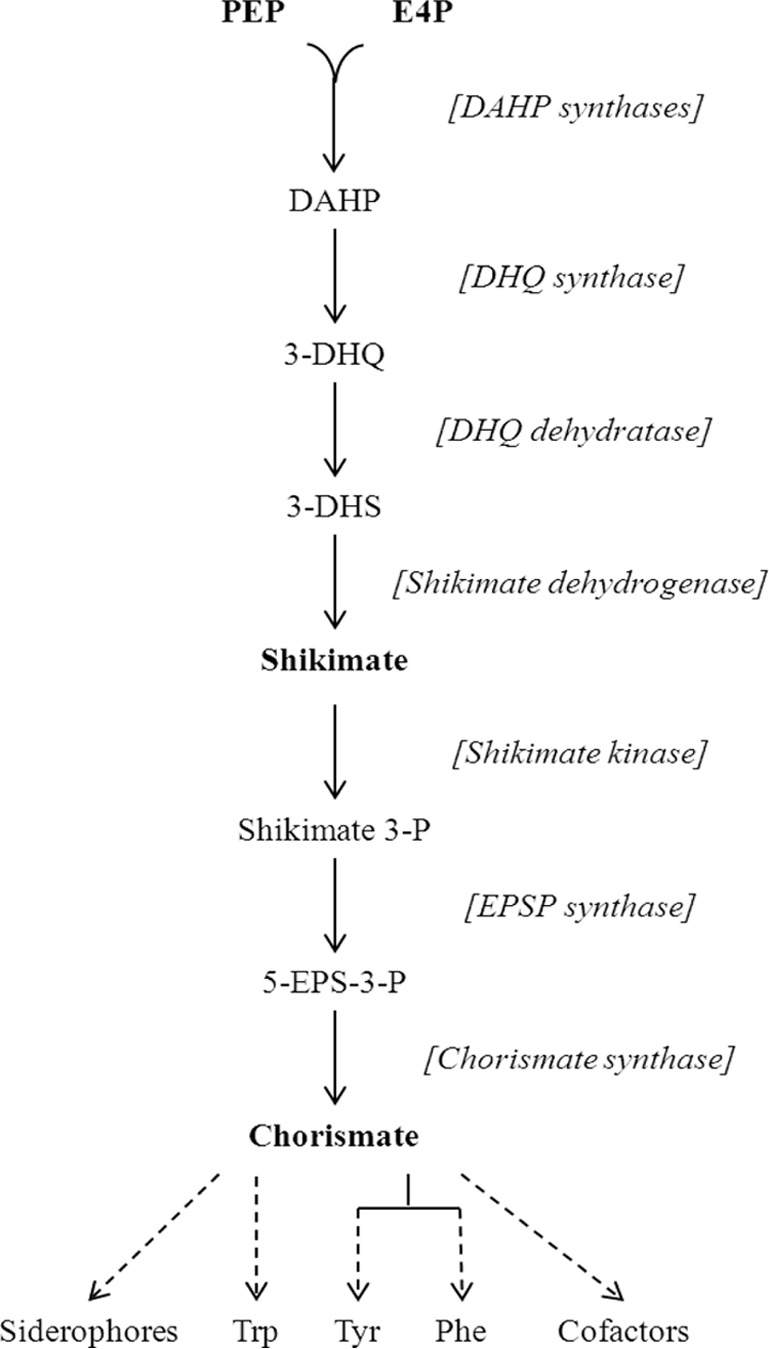

DAHP synthase is a mononuclear iron enzyme that is sensitive to Fenton chemistry.

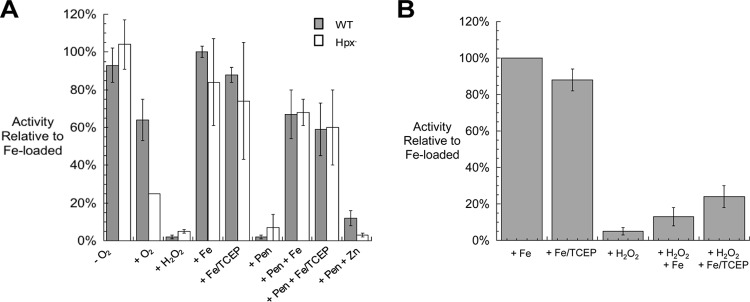

We purified the AroG (Phe-inhibitable) isozyme of DAHP synthase, which is the predominant isozyme under normal growth conditions. As for most mononuclear enzymes (21), its physiological metal cofactor cannot be reliably identified by analysis of the metal content of the purified protein, because its constituent metal dissociates easily and is lost during purification. The apoprotein regained activity when it was incubated with any of three transition metals that are available in E. coli: iron, manganese, and zinc (Fig. 4). Iron conferred the highest activity, whereas manganese was able to activate DAHP synthase to about 70% of the iron-activated sample. Zinc appeared to be a less suitable metal, conferring only 20% of the activity obtained using iron. These three metalloforms were also assayed for their sensitivity to H2O2. Only the iron-metallated isoform was sensitive to H2O2 (Fig. 4). This outcome is chemically reasonable, as only ferrous iron is efficiently oxidized by H2O2. Further, since this behavior matches that of the enzyme in fresh cell extracts and in vivo, this result indicates that under routine growth conditions, iron metallates DAHP synthase in vivo.

FIG 4.

Activities of pure DAHP synthase activated with various metals. Purified apo-DAHP synthase was treated with 50 μM TCEP and 500 μM each metal. The enzyme activities were then determined with or without exposure to 100 μM H2O2. Activities are given relative to Fe-loaded DAHP synthase without H2O2 challenge. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the means of three independent samples.

Metal dissociated from the purified protein more rapidly than from the protein in crude extracts, confounding measurements of inactivation rate. Therefore, cell extracts from anaerobically grown Hpx− cells were used to quantify the rate of inactivation of DAHP synthase by H2O2. The apparent inactivation rate constant was found to be about 500 to 1,000 M−1 s−1 at 0°C. This is slightly lower than the inactivation rate constants (2,000 to 7,000 M−1 s−1 at 0°C) previously measured for three other mononuclear iron-containing proteins: peptide deformylase, threonine dehydrogenase, and ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase (20, 21).

At physiological temperatures, the rate was too rapid to measure. However, measurements from 0 to 20°C indicated an activation energy for the reaction of 10.9 kcal. This value is close to that which we deduced from reference 39 for H2O2 oxidation of DNA-bound ferrous iron (11.8 kcal), with the modest difference probably arising from the effect of the ligand environment upon the reduction potential of the iron atom. Extrapolation of the DAHP synthase value to 37°C predicts a rate constant of 8,000 M−1 s−1. The calculated half-time of DAHP synthase inactivation by 0.3 μM H2O2 would be 5 min.

Damage to DAHP synthase in vivo is different than damage in vitro.

The predicted damage rate contrasts with the much more gradual onset of the growth defect, suggesting that some oxidation events may be reversible. A Fenton reaction between ferrous iron and H2O2 initially generates a ferryl radical, which can decompose into ferric iron and a hydroxyl radical. In principle, hydroxyl radicals that are released into the active site might be expected to irreversibly damage the enzyme. However, a previous study indicated that when the iron atom is coordinated by a cysteine residue, the nascent ferryl radical may immediately oxidize that sulfur ligand, leaving a sulfenic acid moiety but circumventing other polypeptide damage by a hydroxyl radical (21). Sulfenic acid residues can be restored to the native thiolate form by chemical reductants in vitro and by glutaredoxin and/or thioredoxin systems in vivo. The catalytic iron atom of DAHP synthase is in fact liganded by a cysteine residue (Cys61, in addition to His268, Glu302, and Asp326) (40). We tested whether inactivated DAHP synthase could be reactivated after H2O2 damage and whether that reactivation required the reducing agent tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). When DAHP synthase activity was diminished in vivo through the aeration of Hpx− cells, the activity could be recovered completely by the addition of iron to extracts; TCEP was without additional effect (Fig. 5A). This result indicates that by the point of cell lysis, the protein was in its apoprotein form. This outcome may be misleading though, since cellular glutaredoxins/thioredoxins may have reduced cysteine sulfenic derivatives during extract preparation, when oxidative stress ceased as cells were concentrated in pellets. (Because some remetallation may also have occurred, we regard the measured activity as an upper limit of what was present in vivo.) We also tested whether any of the enzyme had been mismetallated with poorly catalytic metals such as zinc; extracts were treated with penicillamine, an avid chelator of zinc (22), prior to reconstitution. This step did not improve the recovery of activity. We conclude that the damaged enzyme accumulates inside H2O2-stressed cells in either the simple apoprotein or sulfenic forms. That is, the diminution of activity during oxidative stress was primarily due to the dissociation of ferric iron after the Fenton reaction, and no firm conclusion can be made regarding concomitant oxidation of the cysteine ligand.

FIG 5.

Reactivation of DAHP synthase that has been inactivated by H2O2 in vivo and in vitro. (A) Cultures were grown exponentially in anoxic glucose medium. An anaerobic sample was harvested, and the remaining cells were diluted to 0.05 OD into oxic medium and cultured to 0.15 OD before harvesting. Where indicated, samples were treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min; 500 μM Fe, Zn, or both Fe and TCEP (Fe/TCEP) for 15 min; or 5 mM penicillamine (Pen) for 20 min followed by Zn, Fe, or Fe/TCEP treatments, prior to the assay. (B) Cell extracts were prepared from anoxically grown cells. Where indicated, samples were treated in vitro with 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min and then with either 500 μM Fe or Fe/TCEP for 15 min prior to the assay. For both panels, the error bars represent the standard deviations from the means of three independent cultures.

In contrast, when DAHP synthase was inactivated in vitro using 100 μM H2O2, only 13% of the activity could be recovered through the simple addition of iron (Fig. 5B). When TCEP was included, up to 24% of the activity was recovered, implying that at least some of the cysteine residues were oxidized to sulfenic acid forms during the H2O2 challenge. This experiment obviously differs from the in vivo study in that the H2O2 concentration was much higher, due to the need for the added H2O2 to stoichiometrically exceed the high-iron pool that was required to ensure metallation (see Materials and Methods). The failure to achieve full reactivation suggests that sulfenic acid residues may have been further oxidized by the high H2O2 level to sulfinic and sulfonic forms. Further work is under way to resolve this question.

E. coli threonine dehydrogenase and peptide deformylase are mononuclear iron-containing enzymes that, like DAHP synthase, use cysteine residues to coordinate the metal. In the apoprotein form, their cysteine residues are exceedingly sensitive to oxidation by H2O2, with rate constants of 1,000 M−1 s−1 and 13,000 M−1 s−1, respectively (21). This is in marked contrast to typical cysteine residues (k = 2 M−1 s−1), and it has the effect of ensuring that apoprotein generated either by demetallation or by new synthesis is quickly converted by H2O2 to a nonmetallatable form. To test whether DAHP synthase exhibits the same behavior, apoprotein was prepared by treating cell extracts with chelator for 30 min. The protein was then exposed to H2O2, and we monitored its conversion to a form that could not be activated by the simple addition of a metal. In contrast to the other two enzymes, the apparent rate constant for oxidation of the apoprotein was only ∼5 M−1 s−1. This rate constant is so low that 0.3 μM H2O2 would require 5 days to oxidize half of the apoprotein. Thus, although physiological doses of H2O2 can rapidly inactivate the DAHP synthase holoenzyme, they have no significant effect upon the apoprotein.

Manganese is able to protect DAHP synthase.

The ability of manganese to protect cells from oxidative environments has long been noted (41–47). Recent data show that manganese specifically protects mononuclear iron-containing enzymes from H2O2 (20, 21). Our standard minimal medium contains very little manganese. As seen in Fig. 6, the addition of manganese enabled Hpx− mutants to grow without aromatic amino acid supplements. As little as 0.5 μM manganese eradicated the aromatic phenotype. The DAHP synthase activity in these cells was between 60 and 70% that of wild-type cells (Fig. 3B), which matched the amount of activity obtained when pure DAHP synthase was metallated with manganese versus iron (Fig. 4). Conversely, when the manganese importer, MntH, was deleted from the Hpx− strain, DAHP synthase activity was even lower than in the Hpx− strain itself, falling to less than 5% of the wild-type activity, near the limit of detection (Fig. 3B). These data are consistent with the notion that in H2O2-stressed cells, the OxyR-induced import of manganese (48) allows it to substitute for iron in DAHP synthase. Direct evidence is currently lacking, however, since the rapid dissociation rate in extracts did not allow us to confirm that manganese itself occupies the active sites of the enzymes recovered from these cells.

FIG 6.

Manganese supplements suppress the aromatic biosynthetic defect of Hpx− cells. Exponentially growing Hpx− cells in anoxic glucose medium were diluted at time zero into oxic medium. Where indicated, 50 μM Mn was added to the medium.

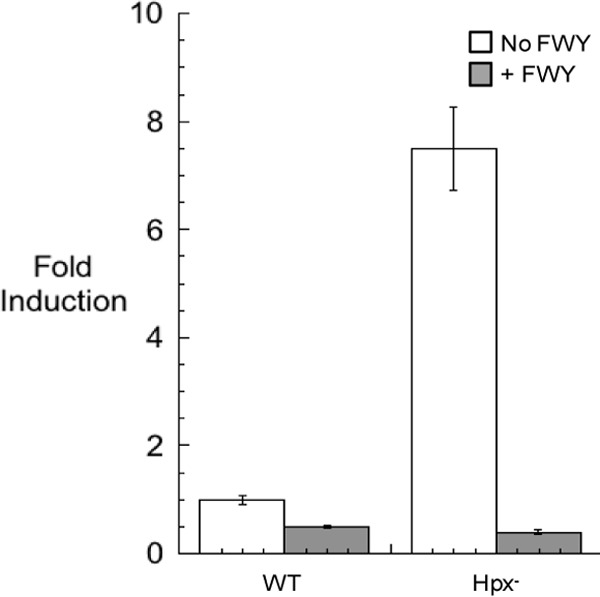

E. coli attempts to compensate for diminished DAHP synthase activity by increasing expression.

The TyrR transcription factor binds tyrosine and represses expression of aroG and aroF, which encode the primary and secondary DAHP synthase isozymes (38). We anticipated that H2O2-stressed cells might partially compensate for the decreased output of the aromatic amino acid biosynthetic pathway by inducing transcription of these genes. Transcriptional fusions to lacZ were constructed and integrated into the lambda attachment site. The β-galactosidase activity arising from the aroG::lacZ fusion was not measurably higher in Hpx− mutants than in wild-type cells, which may reflect the fact that TyrR exerts a very mild (<2-fold) impact on aroG transcription (38). In contrast, in Hpx− strains, transcription of the aroF gene increased by 7.5-fold over wild-type levels (Fig. 7). In a ΔtyrR null strain, aroF expression increased about 28-fold (not shown), consistent with the greater responsiveness that others have reported. Thus, the TyrR response to H2O2 is not complete, but it is apparent that expression increases as a way to compensate for diminished activity of the pathway. Since the aroF-encoded enzyme provides a small fraction of the basal DAHP synthase activity, its induction has a modest effect on total activity.

FIG 7.

aroF transcription increases in response to H2O2 stress. Hpx− strain JS299 containing an aroF::lacZ transcriptional fusion in the lambda attachment site was subcultured into oxic glucose medium and grown for 4 h. Extracts were prepared, and β-galactosidase activity was determined. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the means of three independent cultures.

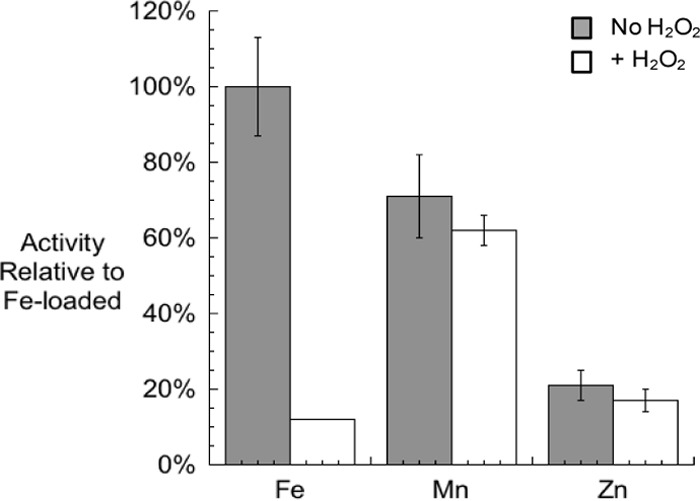

Superoxide stress promotes the mismetallation of DAHP synthase.

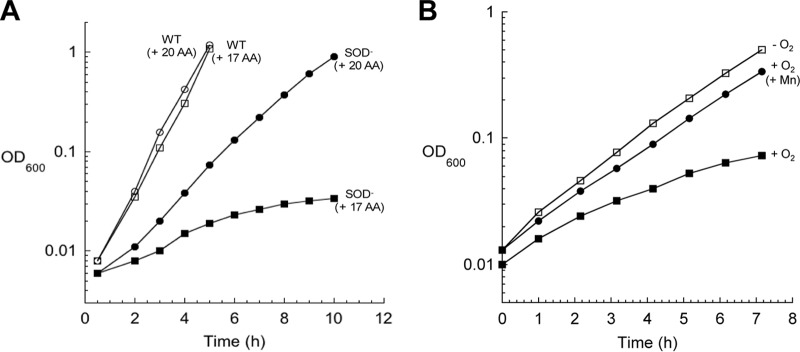

When E. coli superoxide dismutase (SOD) mutants are grown aerobically in defined medium, these cells, like Hpx− mutants, cannot grow without the three aromatic amino acids (Fig. 8A). In 1999, Benov and Fridovich proposed that O2− might oxidize the 1,2-dihydroxyethyl thiamine pyrophosphate reaction intermediate of transketolase (49). Transketolase is the sole pentose phosphate enzyme that is essential for synthesis of erythrose 4-phosphate, the precursor metabolite for aromatic synthesis. We confirmed that the transketolase activity of SOD mutants is approximately half that of wild-type cells (data not shown). However, during growth on glucose, the flux through the pentose phosphate pathway exceeds 30% of the total carbon flux (calculated from reference 50), whereas the branch into the aromatic pathway consumes only ∼1% (51). Therefore, it did not seem possible that a moderate loss of transketolase activity or pentose phosphate flux would impede aromatic synthesis. Furthermore, the aromatic auxotrophy was largely suppressed by the deletion of the fur locus, which leads to rapid import of iron and manganese (52). This observation implied that the phenotype involves transition metals, which transketolase does not use. In fact, when manganese was added to the growth medium, SOD mutants were able to grow nearly as well as wild-type cells (Fig. 8B).

FIG 8.

SOD− mutants are aromatic amino acid auxotrophs. (A) Cultures were grown anaerobically overnight in glucose medium supplemented with 17 amino acids [(+ 17 AA)] (lacking Phe, Tyr, and Trp). At time zero, cells were diluted into oxic medium with or without aromatic amino acids. (B) Cultures were treated as in panel A. Where indicated, 25 μM MnCl2 was added to the medium.

These results suggested that O2− and H2O2 might disable aromatic biosynthesis in similar ways. Recent findings showed that O2− can inactivate several mononuclear iron enzymes by oxidizing the ferrous cofactor to the ferric form, which then dissociates, leaving apoprotein (22). To test whether O2− can directly inactivate the enzyme, purified DAHP synthase that had been metallated with iron was treated with xanthine/xanthine oxidase (to generate O2−) in vitro. This exposure resulted in the loss of 90% of DAHP synthase activity (Fig. 9A). The protein was fully reactivated by the addition of iron, indicating that the in vitro damage was solely due to metal loss. Superoxide cannot oxidize cysteine residues, which likely explains why O2−-treated enzyme was easily reactivatable, while H2O2-treated enzyme was not.

FIG 9.

O2− damages purified DAHP synthase in vitro and in vivo. (A) Purified Fe-loaded DAHP synthase was exposed to O2− generated by xanthine and xanthine oxidase. Catalase was included in all samples. Superoxide stress was terminated by the addition of SOD. All superoxide-treated samples were returned to anoxic conditions and, where indicated, treated with ferrous iron with or without TCEP prior to the assay. Error bars represent the standard deviations from the means of three independent samples. (B) Exponentially growing cultures were diluted from anoxic to oxic glucose medium containing 17 amino acids (lacking Phe, Tyr, and Trp) at time zero. Where indicated, 25 μM MnCl2 was added to the medium. At three different time points, DAHP synthase activity was assayed. (C) Extracts were prepared from wild-type and SOD− cultures after growth to 0.2 OD in oxic medium. Where indicated, samples were treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min, 5 mM penicillamine for 20 min, and 750 μM Fe or Zn for 15 min, prior to the assay. For all panels, the error bars represent the standard deviations from the means of three independent experiments.

This phenomenon also occurred in vivo. When SOD mutants were shifted into an oxic environment, the DAHP synthase activity progressively declined (Fig. 9B). Activity remained much higher in manganese-supplemented cells.

The condition of the DAHP synthase enzyme was also examined after damage in vivo (Fig. 9C). The activity in extracts from SOD mutants was fully restored when the enzyme was treated with penicillamine and iron, confirming that the polypeptide itself was undamaged. The enzyme that was recovered from wild-type cells was sensitive to H2O2, in accordance with iron occupancy of its active site, but the lower residual activity in extracts from SOD mutants was resistant. This result parallels what was observed in an earlier study of ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase and threonine dehydrogenase, in which it was concluded that in SOD mutants, the enzymes were mismetallated with zinc in place of iron (22). Indeed, metallation with zinc after penicillamine treatment generated the starting activity of SOD mutants. To test this idea more directly, theoretical ratios between DAHP synthase reaction rates at two concentrations of E4P were calculated using published Km values (30) and compared to values measured for the DAHP synthase activity recovered from wild-type cells and SOD mutants. As expected, DAHP synthase from wild-type cells was metallated by iron in vivo, while the ratio for SOD mutants indicated that zinc was in the active site (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

DAHP synthase in SOD mutants is mismetallated by Zna

| Protein or source of protein | V (180 μM)/V (3 μM) |

|---|---|

| Metallated proteins | |

| Fe-DAHPS | 17 |

| Mn-DAHPS | 30 |

| Zn-DAHPS | 6 |

| DAHPS from cell extracts | |

| Wild-type cells | 18 (5) |

| SOD− cells | 4.6 (1.4) |

For metallated proteins, the ratio of reaction rates (V) at 180 μM and 3 μM erythrose 4-phosphate was calculated for each of the three metals using published Km values for DAHP synthase: 67 μM for Fe2+, 170 μM for Mn2+, and 16 μM for Zn2+ (30). For DAHPS from cell extracts, extracts were prepared from aerobic SOD− mutants as described in the legend to Fig. 9. Assay reactions were run for 1 min using either 180 μM or 3 μM E4P. The ratios of activity shown are the averages with the standard deviations of three replicates shown in the parentheses.

DISCUSSION

Life arose in an anoxic environment that was rich in iron (53). Iron is facile at catalyzing both redox and surface chemistry, and primordial pathways evolved around its capabilities. Contemporary organisms inherited this common metabolic plan from their forebears—and, with it, a dependence upon iron as a catalytic cofactor. E. coli relies upon iron for its respiratory pathways, pentose phosphate shunt, and TCA cycle; for nitrogen and sulfur assimilation; and for the syntheses of many amino acids, virtually all cofactors, and reduced nucleotides. The few microbes that use scant iron pay the price in terms of limited metabolic capabilities; their energy yields are low, and their biosynthetic deficiencies compel them to assimilate biomolecules from their environment.

The gradual accumulation of oxygen more than 2 billion years ago (53) converted iron usage into a liability. Thus far, all explicated phenotypes of ROS stress involve reactions between oxygen species and iron. DNA damage arises from reactions between H2O2 and DNA-associated ferrous iron (4, 54). Inhibition of the TCA cycle, Entner-Doudoroff pathway, and branched-chain biosynthesis stems from the oxidation of [4Fe-4S] clusters by superoxide or H2O2 (11–15, 19). Failure of the pentose phosphate and aromatic pathways results from the oxidative demetallation of mononuclear iron-containing enzymes (20). Further, it is likely that the disruption of the Isc iron-sulfur assembly system (55) and of iron control (56) stem from analogous ROS-mediated oxidation of scaffold clusters and of the iron-loaded Fur protein, respectively. It may be too soon to determine that oxidative stress is exclusively an iron pathology, but to date, the data support that conclusion.

Why is the aromatic pathway more sensitive than other pathways?

Interestingly, despite the similarity in the underlying chemistry, not all phenotypes arise at the same doses of oxidants. The aromatic auxotrophy that was explored in this study appears at a much lower dose of intracellular H2O2 (∼0.3 μM) than does the branched-chain auxotrophy (∼8 μM)—even though the rate constant with which H2O2 damages DAHP synthase in vitro (500 to 1,000 M−1 s−1) is slightly lower than that for isopropylmalate isomerase (3,800 M−1 s−1 at 0°C) (19). Several factors other than these rate constants come into play in vivo, and these highlight mechanisms that countervail the inhibition of pathways. First, biosynthetic pathways are typically feedback inhibited by end products—so that the initial loss of activity may be offset by the relief of inhibition. The relaxation of transcriptional and translational controls may also compensate; in this study, as DAHP synthase was damaged, repression of aroF by tyrosine-bound TyrR was relieved. However, another, less obvious effect can be mediated by the accumulation of substrate. Isopropylmalate isomerase lies midway in a linear pathway, and so its progressive inactivation is expected to cause isopropylmalate to accumulate. This has two effects. The first is that since physiological substrate concentrations typically do not saturate enzymes, the elevated concentration of the substrate will increase the turnover number of the residual enzyme molecules. That is, since flux control coefficients for midpathway enzymes can be quite low, a moderate diminution of activity may have no impact at all upon pathway flux. Second, the cluster of isopropylmalate isomerase cannot be oxidized when it is complexed by substrate, as the latter occupies all the available iron coordination sites (19). Thus, the rate constant for inactivation progressively decreases as the substrate builds up.

In contrast, DAHP synthase is the first enzyme in the aromatic pathway, and it draws upon a substrate pool that will not increase when the enzyme fails. During growth on glucose, erythrose 4-phosphate is formed by the oxidative pentose pathway, and far more of it is consumed by dissimilation into glycolysis than by entry into aromatic synthesis (50, 51). Bottlenecks in the latter pathway will therefore have no effect upon erythrose 4-phosphate concentration. We speculate that the lack of substrate accumulation means that a protective mechanism that automatically shields isopropylmalate isomerase is unavailable to DAHP synthase.

Protection by manganese.

The genes that are part of the OxyR regulon (57) encode proteins that E. coli uses to minimize the impact of oxidative stress. Key among these strategies are the induction of Dps, an iron-sequestering ferritin, and of MntH, the manganese importer (39, 48, 58, 59). Measurements show that MntH allows cytoplasmic manganese levels to rise by an order of magnitude at the same time that Dps lowers the free-iron level. We suspect that the collective effect is to switch the metals occupying mononuclear enzymes from iron to manganese. Indeed, mutations in either dps or mntH cause general protein carbonylation to rise substantially during periods of H2O2 stress, presumably due to enzyme-associated Fenton chemistry (59). Manganese confers oxidant-resistant activity to DAHP synthase, and in fact the crystal structure of the E. coli AroG isozyme was determined with manganese in the metal site (60).

The same substitution may protect the pathway during periods of (nonoxidative) iron deficiency. The use of iron to activate the enzymes that start the pathway of siderophore biosynthesis is hard to explain unless another metal can substitute under this condition. In fact, MntH induction (but not Dps induction) is a Fur-mediated response to iron starvation (48), and defects in mntH can block the growth of iron-starved cells (61). This change from iron to manganese metallation, which we think is adaptive in E. coli, may be constitutive in lactic acid bacteria, which typically do not import significant iron (62). These bacteria initiate aromatic synthesis using a DAHP synthase whose sequence is homologous to those of the E. coli enzymes and that retains their metal-binding ligands; it seems likely that the enzyme is cofactored by the high (millimolar) intracellular concentrations of manganese that are distinctly characteristic of lactic acid bacteria (41). These ideas will need to be experimentally tested. At present, such experiments are complicated by the tendency of manganese to dissociate from enzymes during the preparation of extracts. We note, in addition, that Daly and coworkers have proposed that complexes of manganese with small biomolecules may also quench oxidative stress (63), perhaps by reducing ferryl or hydroxyl radicals before they produce damage. In any case, lactic acid bacteria have leveraged their resistance to oxidants into a competitive advantage: in oxic environments, many of them excrete copious amounts of H2O2 that can poison other bacteria in their habitats (64).

So why do not all microbes switch to manganese-centered metabolism? A simple answer might be that manganese is less available in many habitats, possibly including the anoxic gut environment that E. coli usually occupies. Beyond this, however, manganese provides enzymes like DAHP synthase with less activity than does iron, which means that more enzyme must be synthesized. Manganese also sticks more poorly to active sites—a consequence of its generally weaker binding to organic ligands, as represented by its position on the Irving-Williams series (65). Thus, intracellular manganese concentrations must be high to ensure full enzyme metallation. Yet high manganese concentrations can be problematic for cells that must use iron for other purposes; for example, excess manganese can hinder the loading of iron into porphyrins and thereby impair the activities of heme enzymes (J. E. Martin and J. A. Imlay, unpublished data).

The nature of damage in vivo depends upon the oxidant.

While O2− and H2O2 appear to target the same classes of proteins, the mechanisms by which the damage occurs are not identical. Superoxide simply displaces iron from DAHP synthase, presumably by oxidizing it to a dissociable ferric form. The apoprotein thus formed is likely to be reactivated by metallation as rapidly as would a newly synthesized apoprotein. However, during each cycle of this process, there is a finite chance that zinc will bind in place of iron—and, once bound, zinc is slow to dissociate. The outcome is the gradual accumulation of less-active zinc-cofactored enzyme. Manganese can protect the aromatic pathway, and we believe that it probably does so by competing with zinc for the active site of the apoprotein. This pattern matches that seen for other mononuclear enzymes (20, 21).

Damage by H2O2 is clearly more complicated. Oxidation of DAHP synthase in vitro generated apoprotein that could not recover activity through the addition of metal. The Fenton reaction generates a strong oxidant within the active site, which we believe can directly oxidize the coordinating cysteine ligand. The ability of TCEP to afford partial reactivation lends support to this view. However, the protein can also be damaged beyond the point of easy repair—either because the sulfenic acid is further oxidized or because hydroxyl radicals can damage other active site residues. The extracts from H2O2-stressed cells suggested that the enzyme was predominantly in an apoprotein form. However, sulfenic residues may have been reduced during cell concentration. Rigorous characterization of the damaged enzyme will require further work.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grant GM49640 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 March 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01573-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loew O. 1900. A new enzyme of general occurrence in organisms. Science 11:701–702. 10.1126/science.11.279.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCord JM, Fridovich I. 1969. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244:6049–6055 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imlay JA. 2013. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11:443–454. 10.1038/nrmicro3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imlay JA, Chin SM, Linn S. 1988. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240:640–642. 10.1126/science.2834821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winterbourn CC, Metodiewa D. 1999. Reactivity of biologically important thiol compounds with superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 27:322–328. 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00051-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bielski BHJ, Richter HW. 1977. A study of the superoxide radical chemistry by stopped-flow radiolysis and radiation induced oxygen consumption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99:3019–3023. 10.1021/ja00451a028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fee JA. 1982. Is superoxide important in oxygen poisoning? Trends Biochem. Sci. 7:84–86. 10.1016/0968-0004(82)90151-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzsimons DW. (ed). 1979. Oxygen free radicals in tissue damage. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawyer DT, Valentine JS. 1981. How super is superoxide? Acct. Chem. Res. 14:393–400. 10.1021/ar00072a005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlioz A, Touati D. 1986. Isolation of superoxide dismutase mutants in Escherichia coli: is superoxide dismutase necessary for aerobic life? EMBO J. 5:623–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo CF, Mashino T, Fridovich I. 1987. α,β-Dihydroxyisovalerate dehydratase: a superoxide-sensitive enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 262:4724–4727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner PR, Fridovich I. 1991. Superoxide sensitivity of the Escherichia coli aconitase. J. Biol. Chem. 266:19328–19333 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner PR, Fridovich I. 1991. Superoxide sensitivity of the Escherichia coli 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase. J. Biol. Chem. 266:1478–1483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liochev SI, Fridovich I. 1992. Fumarase C, the stable fumarase of Escherichia coli, is controlled by the soxRS regulon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:5892–5896. 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flint DH, Tuminello JF, Emptage MH. 1993. The inactivation of Fe-S cluster containing hydro-lyases by superoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 268:22369–22376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. 2001. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:7173–7181. 10.1128/JB.183.24.7173-7181.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. 2001. Hydrogen peroxide fluxes and compartmentalization inside growing Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:7182–7189. 10.1128/JB.183.24.7182-7189.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aslund F, Zheng M, Beckwith J, Storz G. 1999. Regulation of the OxyR transcription factor by hydrogen peroxide and the cellular thiol-disulfide status. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:6161–6165. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang S, Imlay JA. 2007. Micromolar intracellular hydrogen peroxide disrupts metabolism by damaging iron-sulfur enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 282:929–937. 10.1074/jbc.M607646200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobota JM, Imlay JA. 2011. Iron enzyme ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase in Escherichia coli is rapidly damaged by hydrogen peroxide but can be protected by manganese. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:5402–5407. 10.1073/pnas.1100410108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anjem A, Imlay JA. 2012. Mononuclear iron enzymes are primary targets of hydrogen peroxide stress. J. Biol. Chem. 287:15544–15556. 10.1074/jbc.M111.330365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu M, Imlay JA. 2013. Superoxide poisons mononuclear iron enzymes by causing mismetallation. Mol. Microbiol. 89:123–134. 10.1111/mmi.12263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 24.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haldimann A, Wanner BL. 2001. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183:6384–6393. 10.1128/JB.183.21.6384-6393.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasan N, Koob M, Szybalski W. 1994. Escherichia coli genome targeting, I. Cre-lox-mediated in vitro generation of ori- plasmids and their in vivo chromosomal integration and retrieval. Gene 150:51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furdui C, Zhou L, Woodward RW, Anderson KS. 2004. Insights into the mechanism of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (Phe) from Escherichia coli using a transient kinetic analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:45618–45625. 10.1074/jbc.M404753200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weissbach A, Hurwitz J. 1959. The formation of 2-keto-3-deoxyheptonic acid in extracts of Escherichia coli B. I. Identification. J. Biol. Chem. 234:705–709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doy CH, Brown KD. 1965. Control of aromatic biosynthesis: the multiplicity of 7-phospho-2-oxo-3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptonate d-erythrose-4-phosphate-lyase (pyruvate-phosphorylating) in Escherichia coli W. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 104:377–389. 10.1016/0304-4165(65)90343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephens CM, Bauerle R. 1991. Analysis of the metal requirement of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266:20810–20817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnow LE. 1937. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine tyrosine mixtures. J. Biol. Chem. 118:531–537 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prevost K, Salvail H, Desnoyers G, Jacques JF, Phaneuf E, Masse E. 2007. The small RNA RyhB activates the translation of shiA mRNA encoding a permease of shikimate, a compound involved in siderophore synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1260–1273. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staub M, Denes G. 1969. Purification and properties of the 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase (phenylalanine sensitive) of Escherichia coli K12. I. Purification of enzyme and some of its catalytic properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 178:588–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCandliss RJ, Herrmann KM. 1978. Iron, an essential element for biosynthesis of aromatic compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75:4810–4813. 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baasov T, Knowles JR. 1989. Is the first enzyme of the shikimate pathway, 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase (tyrosine sensitive), a copper metalloenzyme? J. Bacteriol. 171:6155–6160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ray JM, Bauerle R. 1991. Purification and properties of tryptophan-sensitive 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:1894–1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramilo CA, Evans JNS. 1997. Overexpression, purification, and characterization of tyrosine-sensitive 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonic acid 7-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 9:253–261. 10.1006/prep.1996.0690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tribe DE, Camakaris H, Pittard J. 1976. Constitutive and repressible enzymes of the common pathway of aromatic biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12: regulation of enzyme synthesis at different growth rates. J. Bacteriol. 127:1085–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park S, You X, Imlay JA. 2005. Substantial DNA damage from submicromolar intracellular hydrogen peroxide detected in Hpx− mutants of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9317–9322. 10.1073/pnas.0502051102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shumilin IA, Kretsinger RH, Bauerle RH. 1999. Crystal structure of phenylalanine-regulated 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli. Structure 7:865–875. 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80109-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Archibald F. 1986. Manganese: its acquisition by and function in the lactic acid bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 13:63–109. 10.3109/10408418609108735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang EC, Kosman DJ. 1989. Intracellular Mn(II)-associated superoxide scavenging activity protects Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae against dioxygen stress. J. Biol. Chem. 264:12172–12178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kehres DG, Zaharik ML, Finlay BB, Maguire ME. 2000. The NRAMP proteins of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli are selective manganese transporters involved in the response to reactive oxygen. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1085–1100. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01922.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tseng HJ, Srikhanta Y, McEwan AG, Jennings MP. 2001. Accumulation of manganese in Neisseria gonorrhoeae correlates with resistance to oxidative killing by superoxide anion and is independent of superoxide dismutase activity. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1175–1186. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02460.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tseng HJ, McEwan AG, Paton JC, Jennings MP. 2002. Virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: PsaA mutants are hypersensitive to oxidative stress. Infect. Immun. 70:1635–1639. 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1635-1639.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Maghrebi M, Fridovich I, Benov L. 2002. Manganese supplementation relieves the phenotypic deficits seen in superoxide-dismutase-null Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 402:104–109. 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00065-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daly MJ, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Valilenko A, Zhai M, Venkateswaran A, Hess M, Omelchenko MV, Kostandarithes HM, Makarova KS, Wackett LP, Fredrickson JK, Ghosal D. 2004. Accumulation of Mn(II) in Deinococcus radiodurans facilitates gamma-radiation resistance. Science 306:1025–1028. 10.1126/science.1103185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kehres DG, Janakiraman A, Slauch JM, Maguire ME. 2002. Regulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mntH transcription by H2O2, Fe2+, and Mn2+. J. Bacteriol. 184:3151–3158. 10.1128/JB.184.12.3151-3158.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benov L, Fridovich I. 1999. Why superoxide imposes an aromatic amino acid auxotrophy in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4202–4206. 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fraenkel DG, Levisohn SR. 1967. Glucose and gluconate metabolism in an Escherichia coli mutant lacking phosphoglucose isomerase. J. Bacteriol. 93:1571–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neidhardt FC, Ingraham JL, Schaechter M. 1990. Physiology of the bacterial cell: a molecular approach. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maringanti S, Imlay JA. 1999. An intracellular iron chelator pleiotropically suppresses enzymatic and growth defects of superoxide dismutase-deficient Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3792–3802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anbar AD. 2008. Elements and evolution. Science 322:1481–1483. 10.1126/science.1163100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rai P, Cole TD, Wemmer DE, Linn S. 2001. Localization of Fe2+ at an RTGR sequence within a DNA duplex explains preferential cleavage by Fe2+ and H2O2. J. Mol. Biol. 312:1089–1101. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang S, Imlay JA. 2010. Hydrogen peroxide inactivates the Escherichia coli Isc iron-sulphur assembly system, and OxyR induces the Suf system to compensate. Mol. Microbiol. 78:1448–1467. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07418.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varghese S, Wu A, Park S, Imlay KRC, Imlay JA. 2007. Submicromolar hydrogen peroxide disrupts the ability of Fur protein to control free-iron levels in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 64:822–830. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05701.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng M, Wang X, Templeton LJ, Smulski DR, LaRossa RA, Storz G. 2001. DNA microarray-mediated transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 183:4562–4570. 10.1128/JB.183.15.4562-4570.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altuvia S, Almiron M, Huisman G, Kolter R, Storz G. 1994. The dps promoter is activated by OxyR during growth and by IHF and sigma S in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 13:265–272. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anjem A, Varghese S, Imlay JA. 2009. Manganese import is a key element of the OxyR response to hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 72:844–858. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06699.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shumilin IA, Bauerle R, Kretsinger RH. 2003. The high-resolution structure of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase reveals a twist in the plane of bound phosphoenolpyruvate. Biochemistry 42:3766–3776. 10.1021/bi027257p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grass G, Franke S, Taudte N, Nies DH, Kucharski LM, Maguire ME, Rensing C. 2005. The metal permease ZupT from Escherichia coli is a transporter with a broad substrate spectrum. J. Bacteriol. 187:1604–1611. 10.1128/JB.187.5.1604-1611.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baureder M, Hederstedt L. 2013. Heme proteins in lactic acid bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 62:1–43. 10.1016/B978-0-12-410515-7.00001-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daly MJ, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Kiang JG, Fukumoto R, Lee DY, Wehr NB, Viteri GA, Berlett BS, Levine RL. 2010. Small-molecule antioxidant proteome-shields in Deinococcus radiodurans. PLoS One 5:e12570. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pericone CD, Park S, Imlay JA, Weiser JN. 2003. Factors contributing to hydrogen peroxide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae include pyruvate oxidase (SpxB) and avoidance of the toxic effects of the Fenton reaction. J. Bacteriol. 185:6815–6825. 10.1128/JB.185.23.6815-6825.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Irving H, Williams RJP. 1948. Order of stability of metal complexes. Nature 162:746–747. 10.1038/162746a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.