Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis expresses the 28-kDa protein HupB (Rv2986c) and the Fe3+-specific high-affinity siderophores mycobactin and carboxymycobactin upon iron limitation. The objective of this study was to understand the functional role of HupB in iron acquisition. A hupB mutant strain of M. tuberculosis, subjected to growth in low-iron medium (0.02 μg Fe ml−1), showed a marked reduction of both siderophores with low transcript levels of the mbt genes encoding the MB biosynthetic machinery. Complementation of the mutant strain with hupB restored siderophore production to levels comparable to that of the wild type. We demonstrated the binding of HupB to the mbtB promoter by both electrophoretic mobility shift assays and DNA footprinting. The latter revealed the HupB binding site to be a 10-bp AT-rich region. While negative regulation of the mbt machinery by IdeR is known, this is the first report of positive regulation of the mbt operon by HupB. Interestingly, the mutant strain failed to survive inside macrophages, suggesting that HupB plays an important role in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent for tuberculosis, is one of the most successful pathogens of the human host that has adapted to the inhospitable environment of the macrophages in which it resides. One of the contributing virulence determinants is the ability to acquire iron from the iron-restricted macrophage environment, where the amount of free iron (Fe3+) is 1 to 10 ng ml−1 (1). Most of the iron is chelated by transferrin and lactoferrin (2), and this, coupled to the inherent insolubility of iron at biological pH (3), contributes to the low availability of iron in vivo, a key defense mechanism of the mammalian host defined as nutritional immunity (4). Pathogenic mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis, express the Fe3+-specific high-affinity siderophores mycobactin (MB) and carboxymycobactin (CMB) upon iron limitation (5, 6). The former is located in the cell envelope, and CMB is the extracellular siderophore that is released to the outside to chelate the insoluble/protein-bound iron (7, 8). A remarkable milestone in the understanding of iron acquisition in M. tuberculosis was the unraveling of the mbt biosynthetic machinery for MB and CMB, which have the same core nucleus (9), and the demonstration of the essentiality of this machinery for survival of the pathogen within macrophages (10).

We first reported HupB as a cell wall-associated 28-kDa iron-regulated protein in axenic cultures of M. tuberculosis; maximal expression was seen in cultures with 0.02 μg Fe ml−1. Increased iron levels resulted in the decreased synthesis of the protein, until at 8 μg Fe ml−1 it was negligible and barely detectable in the cell wall fraction (11). Recently, another study (12) linked the protein (referred to as MDP1) to iron homeostasis; it was shown to bind Fe3+ and function as an iron storage protein like the ferritin superfamily of proteins. Here, we present evidence to prove the role of HupB in siderophore biosynthesis and prove the essentiality of this gene (13) by demonstrating the failure of a mutant strain, defective in HupB biosynthesis, to grow inside macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth.

Mycobacterial strains, listed in Table 1, were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium (with 10% [vol/vol] albumin-dextrose-catalase enrichment [ADC; Difco, MD, USA], 0.2% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80). Middlebrook 7H11 agar medium (with 10% [vol/vol] oleic acid-ADC enrichment [OADC; Difco, MD, USA] and 0.5% glycerol) was used for the growth and maintenance of these strains; for genetic manipulations, they were grown in the media described above with the inclusion of the respective antibiotic (25 μg ml−1 kanamycin [Hi-Media, Mumbai, India] and250 μg ml−1 hygromycin [Invitrogen, CA, USA]). For iron-regulated growth, they were grown in Proskauer and Beck medium under low-iron (0.02 μg Fe ml−1) and high-iron (8 μg Fe ml−1) conditions as reported previously (11). All of the mycobacterial cultures were grown in triplicate for the different experiments detailed below.

TABLE 1.

Mycobacterial strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterial strains | ||

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | Type strain | VLA Weybridge collection |

| M. tuberculosis ΔhupB | hupB knockout strain of M. tuberculosis H37Rv | This study |

| M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 | M. tuberculosis ΔhupB complemented with pMS101 plasmid (see below) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSMT100 | Mycobacterial suicide vector utilized to create mutant strain based on homologous recombination | VLA Weybridge collection |

| pMS1 | 1,074-bp left-flanking region cloned into pSMT100 | This study |

| pMS2 | 1,048-bp right-flanking region cloned into pMS1 to generate pMS2 containing both the left- and right-flanking regions of hupB | This study |

| pSM96 | Mycobacterial high-level expression vector with Kanr and Hygr; contains a strong dnaK mycobacterial promoter upstream of multiple cloning site | VLA Weybridge collection |

| pMS101 | hupB of M. tuberculosis cloned into pSM96 | This study |

Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium with 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin-250 μg ml−1 hygromycin.

Generation of hupB knockout strain of M. tuberculosis.

The upstream (left flank) and downstream (right flank) regions of hupB from M. tuberculosis H37Rv chromosomal DNA were amplified with the Advantage-HF PCR kit (Clontech, CA, USA) using primer pairs listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. PCR was done with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 1 min), annealing, and extension at 68°C (3 min). These amplicons were cloned stepwise into the suicide vector pSMT100 (Table 1) on either end of the hygromycin cassette to generate pMS2. Plasmid pMS2 was introduced into M. tuberculosis by electroporation at 2.5 kV, 25 μF, and 2,000 W (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and plated on Middlebrook 7H11 hygromycin plates.

Confirmation of M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain.

Twelve colonies were selected randomly and screened by PCR using five primer pairs listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material; three were hupB-based primer pairs, and two were hygR-based primer pairs. One of the positive clones, here referred to as the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, was used for further studies.

Southern blotting was done to confirm the loss of hupB in the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB strain. Using the wild-type chromosomal DNA as the template, a 521-bp probe was amplified using a forward primer (5′-CGC AGC GTA AGG GCT ATA TC-3′) and reverse primer (5′-GAA GCC TTT CAC ACC CAC TC-3′) that annealed at positions −285 and −806 upstream of the start point of hupB (within the leuD gene). The probe was labeled using the nonradioactive digoxigenin (DIG) high-prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit (version 10.0; Roche Applied Sciences, Mannheim, Germany). In two separate reactions, genomic DNA isolated from M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant were subjected to digestion with PvuII overnight at 37°C, and the digested fragments were separated on a 1% Tris-acetate-EDTA (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) agarose gel. After denaturation, the DNA fragments were transferred onto a nylon membrane and fixed in a UV cross-linker (UV Stratalinker 1800; Stratagene, CA, USA) at a dosage of 120 mJ cm−2. The membrane was incubated with the probe overnight after 30 min of incubation in the prehybridization buffer (DIG Easy Hyb) at 42°C. The subsequent development of the membrane was done per the instructions in the kit. Briefly, the membrane was washed, incubated in blocking buffer for 30 min, and then incubated with anti-digoxigenin antibody for 30 min. After suitable washes to remove the unbound antibody, the blot was developed with nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate solution. The reaction was stopped by adding Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0).

Complementation of M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain with hupB.

Full-length, 645-bp hupB was amplified from the chromosomal DNA of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (see Table S1 in the supplemental material for primer sequences) using the conditions described above. The purified DNA fragment was cloned into the pSM96 vector (Table 1) and transformed into E. coli DH5α, and transformants were selected using hygromycin as the selectable marker. After screening and confirmation of the clones, the recombinant plasmid pMS101 was isolated and electroporated into the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain as described above, and the complemented strains were selected on kanamycin plates.

Assay of the siderophores mycobactin and carboxymycobactin.

Mycobactin and carboxymycobactin were extracted as ferrisiderophores per published protocols (11, 14). Ferrimycobactin and ferricarboxymycobactin were estimated from their absorbance in ethanol at 450 nm using A1%450 values of 43 and 48, respectively, and their yields were expressed as mg (g cell dry weight)−1.

Expression of HupB by immunoblot analysis.

Expression of HupB was studied by immunoblot analysis as described earlier (11), except that the whole-cell sonicates, instead of the cell wall fraction, were used.

Transcriptional profiling.

High- and low-iron organisms, harvested in mid-log phase upon addition of guanidine thiocyanate solution (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), were resuspended in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and subjected to ribolysis (ZR bashing bead lysis tubes; Zymo Research, CA, USA). Four hundred μl of chloroform was added and centrifuged, and the RNA in the aqueous phase was transferred into a new tube and precipitated at −20°C overnight after the addition of a 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate and a 0.8 volume of isopropanol. The RNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, dried at room temperature, dissolved in 100 μl of RNase-free water, and purified using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Contaminating genomic DNA was removed using a TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion, TX, USA). The concentration of the RNA was determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, DE, USA), and an aliquot was tested for the integrity of 16S and 23S rRNA by agarose gel electrophoresis.

(i) Microarray analysis.

Microarray analysis and data normalization were done commercially by Genotypic Technology Pvt. Ltd. (authorized service provider for Agilent, Bangalore, India) according to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) entry GSE53254.

(ii) qRT-PCR.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of the iron-regulated genes mbtA, mbtB, and bfrB was done to validate the microarray data. One μg of the total RNA was converted to cDNA using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, CA, USA) per the manufacturer's instructions. These three genes and 16S rRNA (internal control) were amplified using primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 4 μl of cDNA (diluted 1:10), 5 pmol of each primer, and 5 μl of 2× SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). Real-time PCR was done with the ABI 7500 fast sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) using the following program: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The difference in gene expression, expressed as fold change, was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method using 16S rRNA as the internal control.

EMSA.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was done to study the binding of HupB/IdeR to the upstream DNA region of mbtB per a published protocol (15), with some modifications. The mbtB promoter DNA (216 bp) was PCR amplified using primers (forward, 5′-ACT GGG TCG GCG GCC ATC TG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCC AAG CTT GGT GCA GAG CAT CGG CGC GG-3′) and end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Board of Radiation and Isotope Technology [BRIT], BARC, Navi Mumbai, India) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Fermentas, Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The reaction mixture contained 1 μM the respective protein and 0.5 ng of labeled probe in a 20-μl reaction mix containing 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT; used only in experiments with IdeR), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 10% glycerol. Divalent metal ions, namely, Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+, were added at a final concentration of 200 μM to the respective reaction mixtures, and Fe2+ was added to the different reaction mixtures as indicated in Results. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, they were run on a 4% polyacrylamide gel at 110 V for 2 h. The gel was dried and exposed to storage phosphor image plates for 3 h and scanned in a storage phosphor imaging workstation (Typhoon Trio+ variable mode imager; GE Healthcare, NJ, USA).

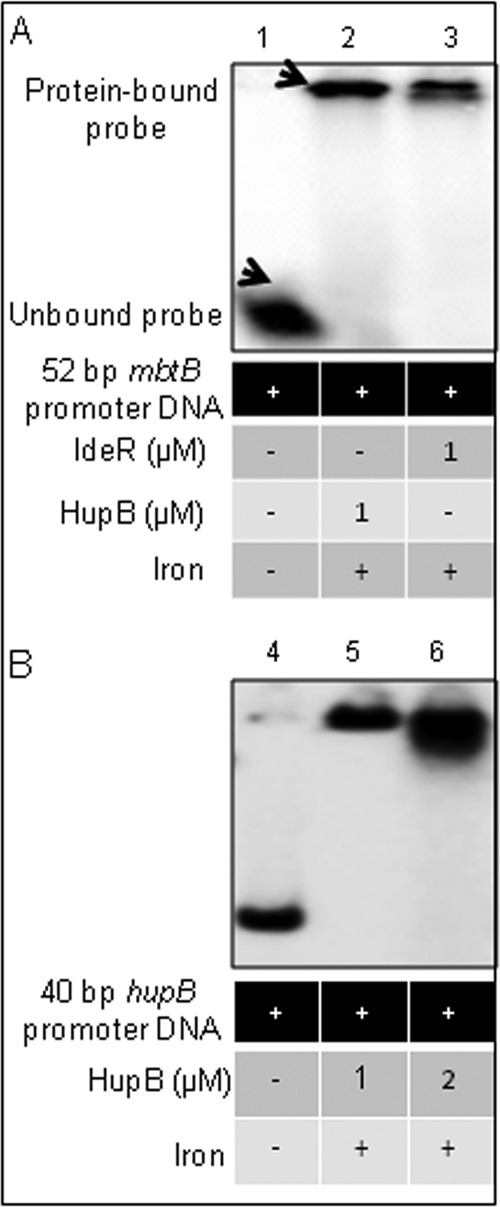

EMSA was also done with the 52-bp mbtB promoter DNA (with IdeR box and HupB-binding domain) and the 40-bp hupB promoter DNA (with HupB-binding domain); details of these two chemically synthesized oligonucleotides are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

DNA footprinting assay.

The [γ-32P]ATP-labeled 216-bp mbtB promoter DNA was digested with HindIII to generate the single-strand-labeled probe. A DNase I protection assay was performed in the presence of purified IdeR/HupB in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing ∼80 kcpm of labeled DNA. Reaction volumes were adjusted to 100 μl with Ca2+ and Mg2+ solutions (final concentrations, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM MgCl2). After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the reaction mixture was treated with 2 μg of DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for 60 s at room temperature, followed by termination of the reaction by the addition of 90 μl of stop solution (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, and 100 μg ml−1 yeast tRNA). The DNA was subsequently extracted with phenol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol), precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in 8 μl of formamide dye mix. Samples were heated at 99°C for 5 min and loaded on a 6% Tris-borate-EDTA polyacrylamide-urea sequencing gel (BROVIGA sequencing gel electrophoresis apparatus; Balaji Scientific Services, Chennai, India), dried at 80°C for 1 h, and subjected to autoradiography. Sanger dideoxy sequencing reactions were performed to identify the protected regions.

Infection of mouse macrophage cell line with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, and the hupB-complemented M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 strains.

The murine peritoneal macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, NY, USA) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Infection of the macrophages was carried out per published protocols (16). The cells were released from the monolayer with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, NY, USA) and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4). Cells (1 × 106 per well) were seeded into 6-well plates (Corning, NY, USA) and allowed to adhere overnight. Organisms of the wild-type, mutant, and complemented strains grown under high and low iron concentrations were harvested at mid-log phase, washed, resuspended in RPMI medium, and vortexed for 2 min with 3-mm glass beads to break up the clumps. The bacterial suspension was then diluted with RPMI medium to achieve a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1. After 4 h, the infected cells were washed twice with warm RPMI to remove nonphagocytosed bacteria, followed by the addition of 1 ml of medium with 10 μg ml−1 gentamicin (HiMedia, Mumbai, India). After incubation for 2 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then maintained in complete RPMI for the rest of the experiment. Cells were processed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 after infection. The macrophage monolayers were washed with PBS and lysed with 500 μl 0.06% SDS in 7H9, and the released bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in 100 μl 7H9 medium. The intracellular bacteria were quantified by ATP assay, qRT-PCR, and plating on solid agar plates to determine CFU, as described below. Two identical experiments were done, with each performed in duplicate to assay each of the three parameters described above.

(i) ATP assay.

The ATP assay was done with the luminescence-based BacTiter-Glo microbial cell viability assay kit (Promega) per the manufacturer's instructions. The luminescence was reported as relative light units (RLU) with a GloMax 96 microplate luminometer (Promega) (17).

(ii) qRT-PCR.

A standard curve was first generated with a known amount of genomic DNA from the wild-type strain. Genomic DNA from the isolated bacterial pellets was extracted as follows. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of 7H9 media, and then 200 μl TE9 buffer (500 mM Tris, 20 mM EDTA, pH 9, containing 10 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, and 2 mg ml−1 proteinase K) was added (18). The mixture was incubated at 58°C for 60 min and then at 97°C for 30 min. The DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol) and precipitated with ethanol, and the dried pellet was resuspended in 25 μl of sterile Milli-Q water. The reaction mixture for qRT-PCR contained 4 μl of the extracted DNA, 5 pmol of the 16S rRNA forward and reverse primers, and 5 μl of 2× SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom).

(iii) Determination of CFU.

Twenty μl of the cell suspension was plated on Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates; hygromycin was included in plates used for plating the mutant and hupB-complemented strains. After 3 weeks, the bacterial colonies on plates were counted.

In silico identification of HupB boxes.

The 10-bp HupB-binding sequence in the mbtB promoter, identified by DNA footprinting, was used to identify homologous sequences in the promoter DNA of several randomly chosen HupB-regulated genes from microarray analysis. The region encompassing bp +20 to −220 relative to the start point of these genes was subjected to multiple-sequence alignment with ClustalW to identify the HupB box.

GEO accession number.

Experimental data and methods determined in the course of this work have been deposited in GEO under accession number GSE53254.

RESULTS

Generation of the mutant strains.

The generation of the hupB knockout mutant and complementation of the mutant strain with hupB is detailed in the supplemental material (see Fig. S1, S2, and S3).

HupB-deficient mutant strain shows altered growth in axenic cultures.

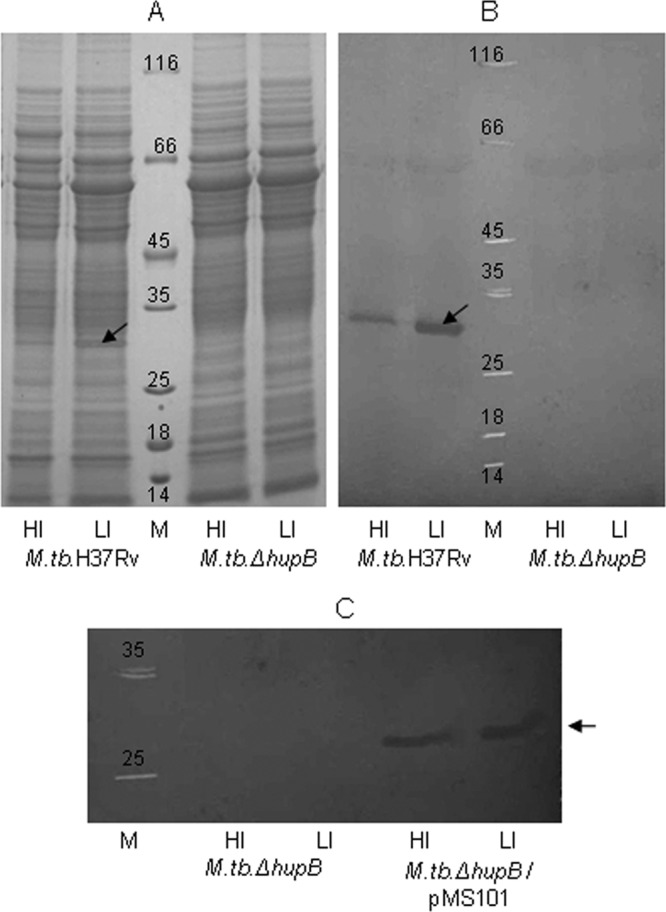

The M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain was defective in the expression of HupB, as demonstrated by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1B). Expression of the protein was regulated by iron in M. tuberculosis H37Rv and was constitutive in the hupB-complemented strain (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

HupB is not expressed by M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant but is constitutively expressed in the hupB-complemented strain. Fifty-μg total protein samples of the whole-cell sonicates of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant grown under high-iron (HI; 8 μg Fe ml−1) and low-iron (LI; 0.02 μg Fe ml−1) conditions were separated electrophoretically by SDS-PAGE (A), transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and developed with rabbit anti-HupB antibodies diluted 1:2,500 (B). (C) Immunoblot showing the constitutive expression of HupB in M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 in both HI and LI organisms (mutant strain is shown for comparison). The arrow indicates HupB, and M is the molecular size marker.

There was a prolonged lag phase in the growth of the mutant strain that was more pronounced in low-iron media (Fig. 2). This was restored in the hupB-complemented strain, which showed growth characteristics similar to those of wild-type M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

FIG 2.

Growth of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, and M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 strains in high- and low-iron media. The three strains were grown under high-iron (HI; 8 μg Fe ml−1) and low-iron (LI; 0.02 μg Fe ml−1) conditions in Proskauer and Beck medium. Growth was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm over a period of 21 days. The experiment was repeated thrice, and the figure represents data from one experiment. The double-headed arrow (↔) represents the lag phase seen in the growth of the mutant strain.

M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain expressed low levels of MB and CMB in low-iron medium.

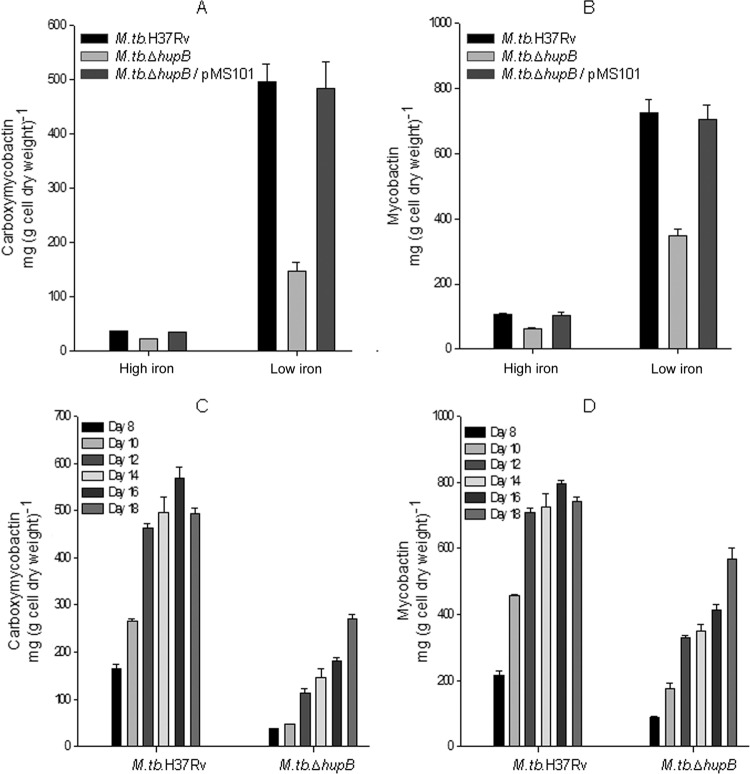

The iron-limited M. tuberculosis ΔhupB strain showed a 3- to 5-fold lower expression of CMB and MB (Fig. 3A and B) than M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The low levels of MB and CMB in the mutant were evident in cultures analyzed over a period of 8 to 18 days (Fig. 3C and D). The levels were restored upon complementation of the mutant with hupB, with almost identical levels seen in iron-limited M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 and M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG 3.

Expression of low levels of mycobactin and carboxymycobactin by the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain and their restoration to normal levels upon hupB complementation. M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, and M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 strains were grown in high (HI, 8 μg Fe ml−1)- and low (LI, 0.02 μg Fe ml−1)-iron media. (A and B) Carboxymycobactin and mycobactin expressed by these organisms harvested after 14 days of growth. (C and D) The time course expression of the two siderophores by M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the mutant strain studied until day 18. The vertical bars represent the standard deviations of the means from three identical experiments.

The mbt biosynthetic machinery is downregulated in the iron-limited M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain: transcriptional profiling by microarray analysis and qRT-PCR.

Microarray analysis showed that all of the mbt genes were downregulated in the low-iron mutant strain; the fold differences of these genes were significant compared to those of the low-iron wild-type strain. Tables 2 and 3 list the mbt genes and all of the other genes influenced by iron and HupB; fold differences of ≥2 were considered. The opposite was true for the iron storage genes; they were downregulated in low-iron wild-type organisms and showed higher transcript levels in the hupB mutant strain (Table 2). qRT-PCR analysis (discussed below) confirmed the microarray data. Table 2 lists the other iron-regulated genes in the wild type, also reported by others (19), whose expression was reversed in the mutant strain. Table 3 shows the three genes Rv1181, Rv1182 (papA3, encoding polyketide synthase associated protein), and Rv1183, possibly organized as an operon, to be downregulated only in the mutant strain. Table 3 also lists those genes whose transcript levels were high upon loss of the hupB gene.

TABLE 2.

Genes influenced by iron and HupB

| Gene and function | Locus no. | Fold change in transcript levela |

Gene productd | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis LI versus HIb | P valuec | LI M. tuberculosis ΔhupB versus LI M. tuberculosis | P valuec | |||

| Mycobactin biosynthesis and iron storage | ||||||

| mbtI | Rv2386c | 5.7123 | 0.0001 | −2.9955 | 0.0014 | Isochorismate synthase MbtI |

| mbtD | Rv2381c | 4.6057 | 0.0000 | −3.0568 | 0.0001 | Polyketide synthetase MbtD |

| mbtB | Rv2383c | 4.5971 | 0.0000 | −3.2997 | 0.0000 | Phenyloxazoline synthase MbtB |

| mbtC | Rv2382c | 4.4677 | 0.0000 | −3.2378 | 0.0000 | Polyketide synthetase MbtC |

| mbtE | Rv2380c | 4.2260 | 0.0000 | −2.5399 | 0.0007 | Peptide synthetase MbtE |

| mbtG | Rv2378c | 4.1033 | 0.0028 | −2.1138 | 0.0045 | Lysine-N-oxygenase MbtG |

| mbtA | Rv2384 | 4.0104 | 0.0001 | −2.2350 | 0.0295 | Bifunctional enzyme MbtA |

| mbtH | Rv2377c | 3.8216 | 0.0000 | −2.2790 | 0.0001 | Putative conserved protein MbtH |

| mbtF | Rv2379c | 2.9341 | 0.0007 | −1.9214 | 0.0008 | Peptide synthetase MbtF |

| bfrB | Rv3841 | −4.3759 | 0.0002 | 2.1293 | 0.0008 | Bacterioferritin BfrB |

| bfrAe | Rv1876 | −1.1001 | 0.0187 | 1.0505 | 0.0473 | Bacterioferritin BfrA |

| Other | ||||||

| esxR | Rv3019c | 1.7064 | 0.0003 | −3.3496 | 0.0001 | Secreted ESAT-6-like protein |

| hisE | Rv2122c | 4.4240 | 0.0000 | −3.2940 | 0.0012 | AMP pyrophosphatase HisE |

| rv0678 | Rv0678 | 1.1304 | 0.0115 | −3.2729 | 0.0012 | CHP |

| mmpS5 | Rv0677c | 1.7504 | 0.0119 | −3.2452 | 0.0010 | CMP, MmpS5 |

| mmpL5 | Rv0676c | 2.7267 | 0.0000 | −3.1554 | 0.0000 | CTMP |

| rv3402c | Rv3402c | 4.3656 | 0.0001 | −3.0883 | 0.0005 | CHP |

| ppe4 | Rv0286 | 1.8776 | 0.0208 | −3.0091 | 0.0044 | PPE family protein |

| eccD3 | Rv0290 | 1.9662 | 0.0013 | −2.9816 | 0.0004 | ESX conserved component EccD3; ESX-3 type VII secretion system protein |

| rv3839 | Rv3839 | 4.5804 | 0.0000 | −2.8439 | 0.0001 | CHP |

| mycP3 | Rv0291 | 1.9005 | 0.0088 | −2.7333 | 0.0021 | Mycosin MycP3 |

| espG3 | Rv0289 | 1.7913 | 0.0167 | −2.7083 | 0.0088 | ESX-3 secretion-associated protein EspG3 |

| rv2028c | Rv2028c | 1.5179 | 0.0004 | −2.6419 | 0.0002 | Universal stress protein family protein |

| rv2030c | Rv2030c | 1.1573 | 0.0043 | −2.5301 | 0.0000 | CHP |

| ppe37 | Rv2123 | 4.5183 | 0.0000 | −2.5139 | 0.0023 | PPE family protein |

| irtA | Rv1348 | 3.8448 | 0.0000 | −2.3819 | 0.0001 | Iron-regulated transporter IrtA |

| irtB | Rv1349 | 3.7224 | 0.0000 | −2.2015 | 0.0001 | Iron-regulated transporter IrtB |

Fold changes of ≥2 in transcript levels were considered.

HI and LI represent high (8 μg Fe ml−1)- and low (0.02 μg Fe ml−1)-iron conditions of growth.

The P values were calculated based on multiple probes used for each gene using the t test method.

Gene products are indicated as described by Mycobacterial Browser (Mycobrowser; Tuberculist version 2.6; http://tuberculist.epfl.ch/), except that the terms “probable” and “possible” are removed. CHP, conserved hypothetical protein; CMP, conserved membrane protein; CTMP, conserved transmembrane protein.

This gene is included even though the fold change is <2.

TABLE 3.

Genes influenced by HupB

| Gene and regulation in M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain | Locus no. | Fold change in transcript levelsa |

Gene productd | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis LI versus HIb | P valuec | LI M. tuberculosis ΔhupB versus LI M. tuberculosis | P valuec | |||

| Downregulated | ||||||

| papA3 | Rv1182 | −0.3505 | 0.6086 | −4.6442 | 0.0008 | Polyketide synthase PapA3 |

| pks4 | Rv1181 | −0.2466 | 0.5339 | −2.8671 | 0.0012 | Polyketide β-ketoacyl synthase Pks4 |

| mmpL10 | Rv1183 | 0.2518 | 0.5756 | −2.7384 | 0.0001 | CTMP |

| Upregulated | ||||||

| rv2087 | Rv2087 | 0.0753 | 0.9265 | 5.6351 | 0.0000 | CHP |

| adh | Rv1530 | 0.0130 | 0.9160 | 4.3850 | 0.0005 | Alcohol dehydrogenase Adh |

| rv0368c | Rv0368c | −0.1614 | 0.3291 | 4.2487 | 0.0001 | CHP |

| phyA | Rv3397c | −0.0639 | 0.6855 | 3.8625 | 0.0005 | Phytoene synthase PhyA |

| rv1128c | Rv1128c | 0.0709 | 0.9691 | 3.8387 | 0.0000 | CHP |

| wbbL2 | Rv1525 | 0.1132 | 0.6176 | 3.3595 | 0.0001 | Rhamnosyltransferase |

| rv0370c | Rv0370c | 0.4890 | 0.7476 | 3.3381 | 0.0003 | Oxidoreductase |

| rv2813 | Rv2813 | −0.3329 | 0.6245 | 3.3066 | 0.0001 | CHP |

| rv3468c | Rv3468c | 0.4669 | 0.0427 | 3.1401 | 0.0000 | Glucose 4,6-dehydratase |

| rv2650c | Rv2650c | −0.3239 | 0.2691 | 3.0965 | 0.0002 | PhirV2 prophage protein |

| rv0369c | Rv0369c | 0.0473 | 0.9359 | 3.0357 | 0.0001 | Membrane oxidoreductase |

| rv1672c | Rv1672c | −0.4033 | 0.3545 | 2.8369 | 0.0030 | CMP |

| rv3467 | Rv3467 | 0.3043 | 0.4444 | 2.7850 | 0.0001 | CHP |

| ppe63 | Rv3539 | −0.2336 | 0.2688 | 2.7844 | 0.0001 | PPE family protein |

| rv1531 | Rv1531 | −0.1800 | 0.5454 | 2.7837 | 0.0017 | CHP |

| rv1371 | Rv1371 | −0.4599 | 0.0010 | 2.7471 | 0.0039 | CMP |

| eccD4 | Rv3448 | 0.1652 | 0.5485 | 2.7374 | 0.0720 | ESX conserved component EccD4; ESX-4 type VII secretion system protein |

| ppsC | Rv2933 | 0.2150 | 0.1214 | 2.7292 | 0.0084 | Polyketide synthase PpsC |

| ptrBa | Rv0781 | −0.1376 | 0.1433 | 2.7287 | 0.0000 | Protease oligopeptidase B |

| ugpC | Rv2832c | 0.1324 | 0.6836 | 2.6397 | 0.0000 | Sn-glycerol-3-phosphate transport ATP-binding protein |

| vapB18 | Rv2545 | 0.2859 | 0.5003 | 2.6258 | 0.0001 | Possible antitoxin VapB18 |

| rv1730c | Rv1730c | 0.4089 | 0.6665 | 2.6037 | 0.0086 | Penicillin-binding protein |

| rv3529c | Rv3529c | 0.0210 | 0.8116 | 2.6024 | 0.0000 | CHP |

| nat | Rv3566c | −0.0945 | 0.6782 | 2.5998 | 0.0009 | Arylamine N-acetyltransferase |

| rv3530c | Rv3530c | −0.0996 | 0.6622 | 2.5953 | 0.0006 | Oxidoreductase |

| iunH | Rv3393 | 0.4561 | 0.0181 | 2.5347 | 0.0000 | Nucleoside hydrolase |

| rv3376 | Rv3376 | 0.2323 | 0.2552 | 2.5015 | 0.0000 | CHP |

Fold changes of ≥2 in transcript levels were considered.

HI and LI represent high (8 μg Fe ml−1)- and low (0.02 μg Fe ml−1)-iron conditions of growth.

The P values were calculated based on multiple probes used for each gene using the t test method.

Gene products are indicated as described by Mycobacterial Browser (Mycobrowser; Tuberculist version 2.6; http://tuberculist.epfl.ch/), except that the terms “probable” and “possible” are removed. CHP, conserved hypothetical protein; CMP, conserved membrane protein; CTMP, conserved transmembrane protein.

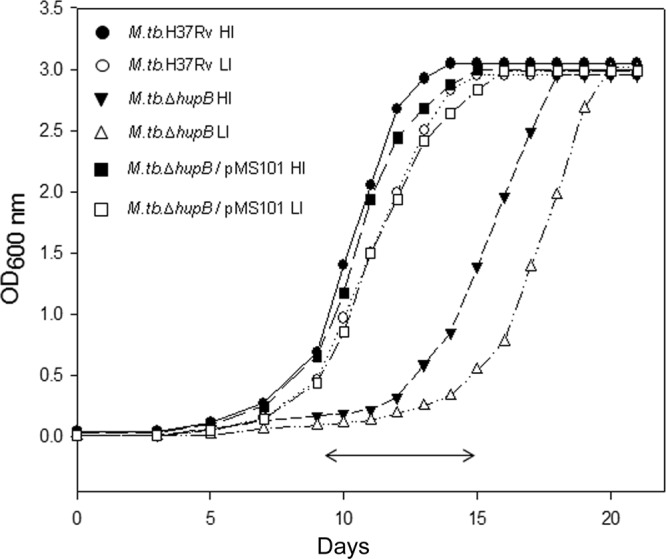

The transcript levels of mbtA and mbtB, representative of the mbt biosynthetic machinery, were confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 4). The fold change of mbtB under low- versus high-iron conditions was 27 ± 0.37 (means ± standard deviations [SD]) in M. tuberculosis H37Rv but decreased to 2.6 ± 0.18 in the mutant strain; the transcript levels were restored in the hupB-complemented strain in which a fold change of 24 ± 0.16 was observed. These transcript levels correlated well with the changes observed in the levels of the two siderophores in cultures. A similar pattern was observed with mbtA (Fig. 4). The reverse was observed for the transcript level of bfrB encoding the iron storage protein BfrB, i.e., a negative fold change of the transcript levels of low- versus high-iron-grown organisms of both M. tuberculosis H37Rv (−12.8 ± 1.57) and the hupB-complemented (−12.5 ± 4.55) strains with a fold change of 1.97 ± 0.57 in the mutant strain correlated with the microarray data. These observations indicated beyond doubt that HupB played a role in the expression of the iron acquisition machinery in M. tuberculosis.

FIG 4.

qRT-PCR analysis of transcript levels of the iron-regulated genes mbtA, mbtB, and bfrB. RNA was prepared from high (HI; 8 μg Fe ml−1)- and low (LI; 0.02 μg Fe ml−1)-iron organisms of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, and the hupB-complemented strains. The mRNA transcript levels of mbtA, mbtB, and bfrB in HI and LI organisms were normalized with 16S rRNA. The graph shows the fold changes of their levels in M. tuberculosis H37Rv LI versus HI, M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant LI versus HI, LI M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant versus LI M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and the hupB-complemented strain M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 LI versus HI.

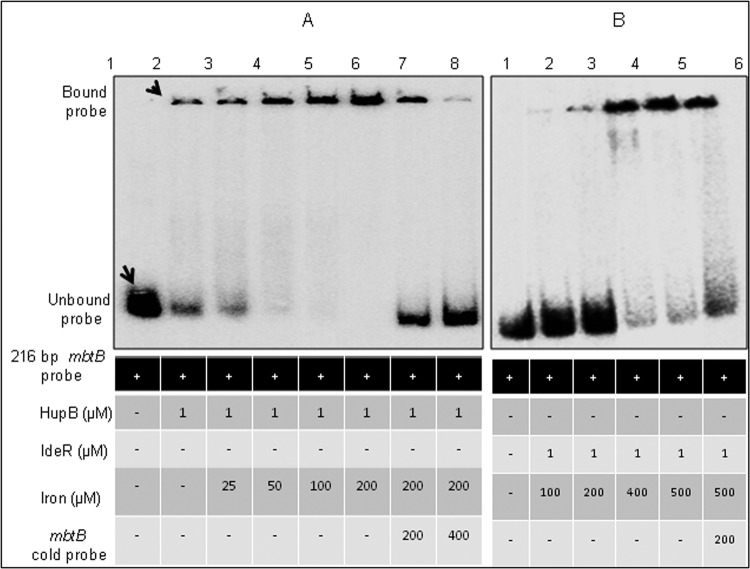

HupB binds mbtB promoter DNA strongly in the presence of iron.

Reduced transcripts of the mbt genes and markedly low levels of MB and CMB in the mutant in low-iron medium clearly indicated a role for HupB in siderophore biosynthesis. Hence, we explored the regulatory role of HupB by assessing its ability to bind the promoter region of mbtB, the first gene in the mbt biosynthetic machinery. IdeR, a known repressor of the mbt genes (15), was used as a positive control, as it is proved to bind the IdeR box in the mbtB promoter. Since electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) with IdeR are done with divalent metal ions like Zn2+, a similar procedure was adopted for HupB-binding studies. It was observed that iron, but no other divalent metal ion, facilitated the binding of HupB with the mbtB promoter DNA (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Figure 5 shows that increasing levels of iron promoted the binding of HupB to the mbtB promoter. It may be noted that low levels of the bound probe could be detected even in the absence of iron (lane 2), and low concentrations of added iron (25 and 50 μM; lanes 3 and 4) strongly promoted the binding of HupB to the promoter DNA. The specificity of this binding was proved by the displacement of the label upon addition of cold probe (lanes 7 and 8). It was interesting that IdeR, which did not bind DNA in the absence of iron (Fig. 5B, lane 1), required an almost 10-fold higher concentration of iron (200 μM) in the reaction mixture to bind the mbtB promoter. This observation supports our proposed hypothesis on the positive regulation of HupB on siderophore biosynthesis.

FIG 5.

EMSA of iron levels and the binding of HupB/IdeR to the mbtB promoter DNA. (A and B) EMSA performed with HupB (A) and IdeR (B). One μM the respective purified protein was added to the 216-bp [γ-32P]ATP-labeled mbtB promoter DNA in the presence of various concentrations of iron. Lane 1 shows the unbound probe in both panels. The intensity of the HupB-bound probe, also detected in the absence of iron (A, lane 2), increased with iron added from 25 to 200 μM (A, lanes 3 to 6). The high level of the bound probe in lane 6 was displaced upon addition of cold probe (lanes 7 and 8). In panel B, lanes 2 to 5 represent IdeR with iron added from 100 to 500 μM. The reaction products were resolved on 4% Tris-acetate polyacrylamide gel.

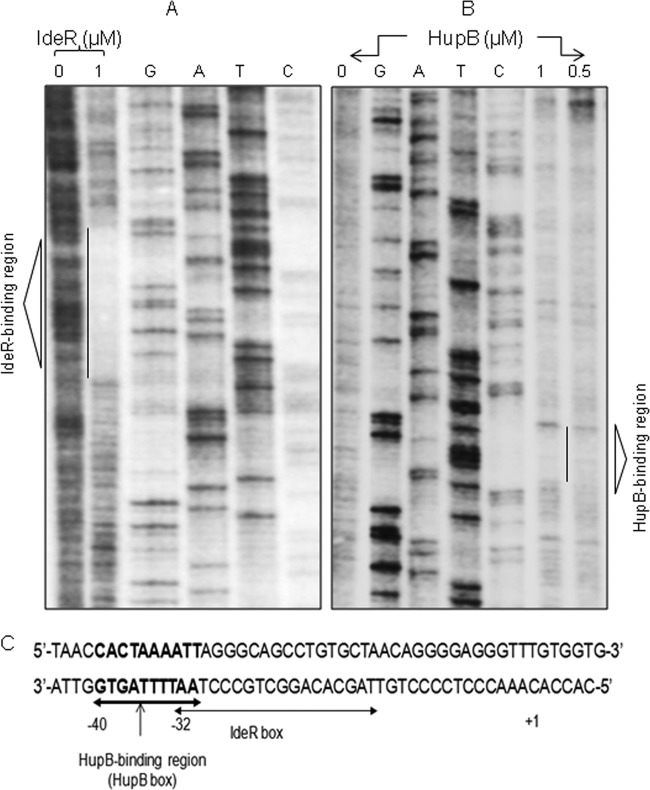

Identification of the 10-bp HupB-binding domain by DNA footprinting analysis.

A DNase I protection assay was performed with the 216-bp mbtB promoter DNA that carried the 19-bp IdeR box (5′-TTA GGG CAG CCT GTG CTA A-3′) located −32 bp upstream of the predicted open reading frame (ORF) start site of mbtB. In agreement with the published data, IdeR bound this region (Fig. 6A), and interestingly, we observed that HupB bound to a 10-bp AT-rich domain (5′-CAC TAA AAT T-3′) further upstream of the IdeR box (Fig. 6B and C). We refer to this region as the HupB box. This sequence was identified in 16 randomly chosen HupB-influenced genes identified in the microarray analysis (Table 4). Interestingly, the HupB box was also identified in the hupB promoter region.

FIG 6.

Identification of the AT-rich HupB box by DNA footprinting. (A and B) Footprint of the [γ-32P]ATP-labeled 216-bp reverse strand of the mbtB promoter DNA protected by IdeR and HupB, respectively, from DNase I digestion. Concentrations of the respective proteins and control (no protein) are indicated. G, A, T, and C represent the ladder generated by Sanger's dideoxy method, as resolved on a 6% Tris-borate-EDTA polyacrylamide sequencing gel containing 8 M urea. The protected regions are indicated by vertical lines and marked as the IdeR box and the HupB-binding region (HupB box) in the respective gels. (C) mbtB promoter DNA and the positions of the IdeR box and HupB box with reference to the start site, indicated by +1.

TABLE 4.

Presence of HupB box in the promoter region of HupB-regulated genes

| Misa | Gene | Locus no. | HupB boxb | Locc | Gene productd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | mbtB | Rv2383c | CACTAAAATT | −40 | Phenyloxazoline synthase |

| 1 | ptrBa | Rv0781 | AACTAAAATT | −34 | Protease oligopeptidase b |

| 1 | rv1578c | Rv1578c | GACTAAAAAT | −24 | phiRv1 phage protein |

| 2 | hupBe | Rv2986c | CAGTGAAATT | −99 | HupB 28–kDa iron–regulated protein (11) |

| 2 | rv1733c | Rv1733c | CAATAAAACT | −121 | Conserved transmembrane protein |

| 3 | mbtA | Rv2384 | CCCTAATTTT | −72 | Salicyloyl-AMP ligase |

| 3 | mmpS5 | Rv0677c | CTCTGAAATC | −71 | Conserved membrane protein |

| 3 | rv0678 | Rv0678 | CAGTGAAACT | −11 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 3 | rv3468c | Rv3468c | CGCGAAAAGT | −76 | Glucose 4,6-dehydratase |

| 3 | papA3 | Rv1182 | CACAAAGATC | −131 | Polyketide synthase protein |

| 3 | ppe63 | Rv3539 | CGCTAAAGGT | −124 | PPE family protein |

| 3 | rv1730c | Rv1730c | CAACCAAATT | −210 | Penicillin-binding protein |

| 4 | rv0368c | Rv0368c | CGCTAGAAGC | −190 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 4 | phyA | Rv3397c | CACCGTAGTT | −20 | Phytoene synthase |

| 5 | rv2087 | Rv2087 | CACCGATGCT | −5 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 5 | bfrB | Rv3841 | TATTATCATC | −91 | Bacterioferritin |

| 5 | esxR | Rv3019c | CGCCAAGGTC | −143 | Secreted ESAT-6-like protein |

Mismatch with the 10-bp HupB box (HupB-binding motif) in the mbtB promoter DNA experimentally proved in this study.

Putative HupB boxes (5′ to 3′).

Location of putative HupB box with reference to the start site.

Gene products are indicated as described by Mycobacterial Browser (Mycobrowser; Tuberculist version 2.6; http://tuberculist.epfl.ch/), except that the terms “probable” and “possible” are removed.

This was used to prove the functionality of the HupB box in this study (Fig. 7B).

EMSA showing the strong interaction of HupB and IdeR with the 52-bp mbtB promoter DNA (Fig. 7A) reaffirmed the presence of both the IdeR and HupB boxes in this region of the mbtB promoter. As the two boxes are adjacent to each other and it is difficult to synthesize a fragment containing only the HupB box in the mbtB promoter, a 40-bp chemically synthesized DNA from the hupB promoter region (Table 4) was used in EMSA, and Fig. 7B unambiguously confirms the presence of the HupB box in this DNA fragment.

FIG 7.

EMSA confirmation of the binding of HupB to the 10-bp AT-rich HupB box. (A) A chemically synthesized 52-bp mbtB promoter region, containing the IdeR box and the HupB box, was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and subjected to EMSA (as done earlier; iron was added at 200 μM) in the presence of HupB (lane 2) and IdeR (lane 3); lane 1 served as a control showing the unbound probe in the absence of any added protein. (B) To confirm further the binding of HupB to the 10-bp HupB-binding motif, a 40-bp oligonucleotide containing the putative HupB box in the hupB promoter (identified by in silico analysis; Table 4) was subjected to EMSA. Lane 4 shows the unbound probe, and lanes 5 and 6 show increasing amounts of the bound 40-bp probe upon addition of increasing amounts of the HupB protein.

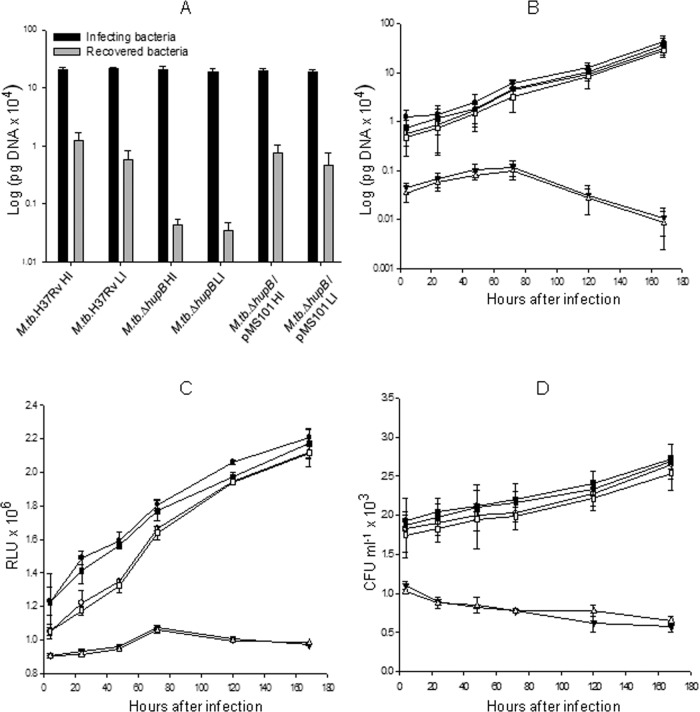

Essentiality of the hupB gene for survival inside macrophages.

The recovery of the wild-type, mutant, and hupB-complemented M. tuberculosis strains 4 h after infection of the mouse macrophage cell line (Fig. 8A) clearly demonstrated the failure of the mutant to gain entry into the macrophage that was reversed in the hupB-complemented strain. Further, those mutant organisms that gained entry failed to survive inside the macrophages. This was evident in the number of bacteria recovered from days 0 to 7 as assayed by qRT-PCR, ATP assay, and CFU analysis (Fig. 8B, C, and D, respectively).

FIG 8.

Infectivity and survival of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, and the hupB-complemented M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 strains inside macrophages. Cells (106) of the mouse peritoneal macrophages (RAW 264.7 cell line) seeded in a 6-well plate were infected with high-iron-grown M. tuberculosis H37Rv (●), M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant (▼), and M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 (■) strains and the respective low-iron-grown organisms (M. tuberculosis H37Rv, ○; M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, Δ; M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101, □) at an MOI of 10:1. (A) The number of cells recovered from the macrophages 4 h after infection (determined by qRT-PCR) was considered the number of cells that gained entry into the macrophages (and time zero for studying the viability inside macrophages), and subsequent isolation of bacilli from the macrophages was done on days 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7. The number of viable bacilli in each of the wells was assayed by both ATP assay (B) and qRT-PCR analysis based on 16S rRNA (C); this was assayed in triplicate. Two such identical experiments were done for each of the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant and M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 strains. (D) The number of viable bacilli determined as CFU.

DISCUSSION

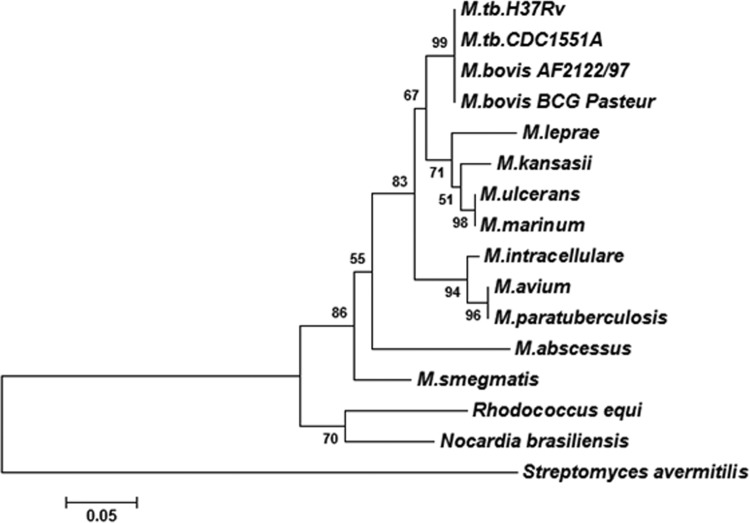

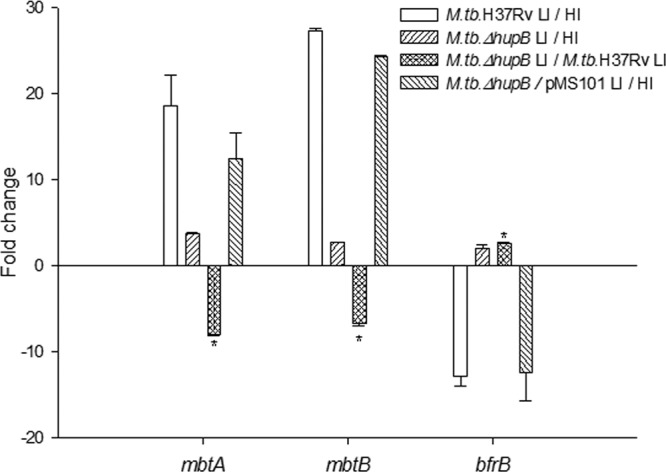

HupB is expressed by many mycobacterial species, including M. leprae, in which it is conserved despite a severe reduction in genome size relative to other mycobacteria. In M. tuberculosis, HupB is a 22-kDa protein that migrates as a 28-kDa protein due to the net positive charge contributed by the lysine and arginine residues in the C-terminal end. The latter is unique to mycobacteria, while the N-terminal region shows strong homology with the 90-amino-acid-rich HU-binding protein of E. coli. The HupB orthologs in mycobacterial species differ by about 20 to 30% in their primary sequence, and Fig. 9 shows a phylogenetic tree depicting the relatedness among these orthologs. HupB is 214 amino acids long in M. tuberculosis and shows deletions of approximately 9 to 14 amino acids in the C-terminal region in other mycobacteria. It is not clear if these deletions (9 in BCG strains and 14 in M. leprae) play a role in the function of the protein. Its role in iron metabolism, first reported by us (11), was strengthened by the recent report on the ferritin-like role of HupB due to its ability to chelate Fe3+ (12). Based on our earlier observation of the coexpression of HupB with MB and CMB in iron-deprived M. tuberculosis, we explored the functional role of the protein in this study. We generated a hupB knockout strain of M. tuberculosis and compared the expression profiles of iron-limited M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant and M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The salient observations in this study are the following: (i) the HupB-deficient M. tuberculosis ΔhupB strain expressed low levels of MB and CMB upon iron limitation, and complementation of the mutant with hupB restored the siderophore production to normal; (ii) HupB binds the mbtB promoter upstream of the IdeR box, and DNA footprinting identified the HupB box (HupB-binding region) to be a 10-bp AT-rich sequence; and (iii) the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant strain failed to survive within macrophages, indicating the essentiality of the hupB gene in vivo.

FIG 9.

Phylogenetic tree of HupB in mycobacteria. The figure shows the evolutionary relatedness of HupB in different mycobacterial species. The tree was generated using the MEGA tool (version 5). ClustalW software (built into MEGA5) utilizing the BLOSUM score matrix was used for pairwise and multiple-sequence alignment. The phylogenetic tree was constructed utilizing the neighbor-joining method. The robustness of the tree was determined using bootstrapping with 5,000 replicates.

There was a notable decrease in MB and CMB in M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant versus wild-type organisms grown under low-iron conditions. This was reflected both in the transcript levels of the mbt genes (microarray and qRT-PCR analyses) and the levels of the two siderophores in active cultures. This led us to study the role of HupB in siderophore production, and we provide evidence to show that HupB exerted a positive regulatory role on the mbt biosynthetic machinery. The mbt genes are located at two loci. The first, called the mbt1 cluster and spanning 24 kb of the M. tuberculosis genome, consists of 10 genes, mbtA-J (9), while the second locus is denoted the mbt-2 cluster (20) and consists of four genes, mbtK-N. The mbt1 cluster contains the core components necessary for mycobactin biogenesis, and the mbt2 cluster is involved in the incorporation of the lipophilic aliphatic side chain. MbtB (encoded by mbtB in the mbt1 cluster) catalyzes the first step in this biosynthetic machinery; hence, mbtB has been used as a target gene for studying the regulation of the mbt operon in M. tuberculosis (15) and for demonstrating the essentiality of this operon for the pathogen's survival in low-iron media and inside macrophages (10). The iron regulator IdeR negatively regulates mbtB expression, as the IdeR-Fe2+ complex formed under high-iron conditions binds the IdeR box, thereby blocking the transcription of mbtB (15). In this study, using DNA footprinting analysis, we identified the 10-bp AT-rich HupB box (5′-CAC TAA AAT T-3′) at the bp −40 position upstream of the IdeR box (located at bp −32 upstream) relative to the transcriptional start point of mbtB. Binding of HupB to the identical HupB box in the hupB promoter region (Fig. 7B) confirms the functionality of the HupB box.

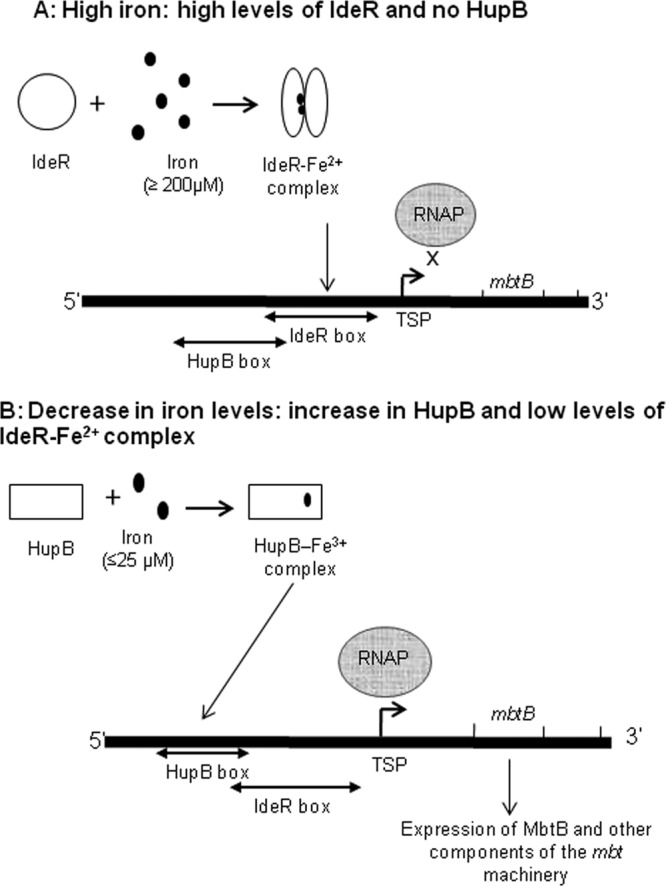

The influence of HupB on the expression of MB and CMB and its ability to bind the mbtB promoter lead us to propose that HupB functions as a positive regulator of siderophore production. Figure 10 is a diagrammatic representation of the sequence of events occurring under high- and low-iron conditions that explains the repressor effect of IdeR and the positive regulatory role of HupB on the expression of mbtB. Figure 10A shows the sequence of events that occur under high-iron conditions when IdeR is present and HupB is absent: the IdeR-Fe2+ complex binds the IdeR box and blocks transcription of mbtB by RNA polymerase. When there is a drop in the iron levels inside the cell, IdeR can no longer form the complex, as we demonstrated (Fig. 5), as it requires a high concentration of iron (200 μM) to form this complex. Iron-regulated expression of HupB in M. tuberculosis, reported earlier (11), showed that the protein can be detected even at 144 μM (8 μg Fe ml−1), with complete repression occurring only at 216 μM (12 μg Fe ml−1) iron in the medium of growth. Thus, when IdeR and iron levels start falling, HupB levels rise and can bind the HupB box in the presence of available iron. HupB was demonstrated to bind the mbtB promoter (Fig. 5) even in the presence of very low levels of iron (25 μM). It is likely that the organism ensures adequate levels of HupB even at moderate iron concentrations in order to immediately trigger the mbt machinery without any delay upon sensing a fall in the iron levels. It may be pointed out that the presence of iron profoundly influenced the binding of the protein to the mbtB promoter DNA, as negligible label was seen in the presence of the desferri form of the protein. The binding is specific to iron, as other divalent metal ions do not promote the binding of HupB to the HupB box. It is likely that HupB binds the mbtB promoter DNA as a HupB-iron complex at the HupB box, located upstream of the IdeR box, that is empty due to the absence of the IdeR-Fe2+ complex; therefore, transcription by RNA polymerase can occur and mycobactin is synthesized. This proposed function of HupB is strengthened by the ability of the low-iron-grown HupB-complemented M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 strain to produce amounts of MB and CMB equivalent to those of the iron-limited wild-type M. tuberculosis H37Rv. It may be mentioned that the M. tuberculosis ΔhupB/pMS101 strain, which constitutively expresses HupB, does not produce siderophores under high-iron conditions; this may be explained in light of the fact that, despite the expression of HupB, the IdeR-Fe2+ complex formed under iron-sufficient conditions binds the IdeR box and prevents transcription of the mbt machinery. It remains to be ascertained if there is an alternative possibility of a direct interaction of HupB with RNA polymerase. Matsumoto and his group (21), in their first report on the HupB protein (which they called MDP1), demonstrated the protein on 50S rRNA as well as on the cell surface, as also reported by us (11). It remains to be studied if the protein in the different locations shows any posttranslational modification(s), such as methylation/acetylation, due to the large number of lysine residues in its C-terminal region. Also, it would be worthwhile to study whether any additional functional role(s) of HupB exists that is linked to its presence in different locations. Of particular interest would be the role of the protein on the transport of iron, specifically on the ESX-3 locus, as the latter has been proved to play an important role in the mycobactin-mediated iron transport in mycobacteria (22). The downregulation of esxR and espG3 (Table 2), components of the ESX-3 locus, and the presence of the HupB box upstream of esxR clearly warrant further studies to understand better the iron acquisition machinery and the role of HupB on siderophore (iron) transport.

FIG 10.

Role of IdeR and HupB in the regulation of the mbt biosynthetic machinery in M. tuberculosis and the sequence of events occurring under high- and low-iron conditions. (A) Using mbtB as the representative gene for the mbt operon, the events occurring under high-iron conditions are represented. When iron is present in sufficient amounts (≥200 μM), there is no transcription of mbtB, as the IdeR-Fe2+ complex that is formed occupies the 19-bp IdeR box in close vicinity of the transcriptional start point (TSP). HupB is not expressed under these conditions. (B) Sequence of events that occur when the iron levels begin to fall. IdeR is unable to form the IdeR-Fe2+ complex in the presence of decreasing levels of iron, and the induced HupB, detectable at 144 μM iron, now can bind the HupB box in the presence of available iron (it can bind even at 25 μM, as shown in Fig. 5). The empty IdeR box and the presence of HupB at the HupB box, located upstream of the IdeR box, favors transcription of mbtB by RNA polymerase (RNAP).

The M. tuberculosis ΔhupB mutant, first isolated from hygromycin plates after transformation of wild-type organisms, failed to grow in low-iron axenic medium (results not shown) but did grow when organisms were passaged in media with a stepwise decrease of iron adapted to the in vitro conditions. However, the growth rate of the mutant, even under high-iron conditions, was low, and it took longer for the mutant to reach a cell density equivalent to that of the wild-type organism. Interestingly, the low-iron mutant strain failed to grow inside the macrophages, proving that HupB is essential in vivo. Our observations are in agreement with Sassetti et al. (13), who reported the essentiality of the hupB gene. Thus, HupB is essential for survival, as it plays an important role in siderophore production. In the wake of these observations and the observations by others (mentioned above), it is highly likely that HupB has an additional role(s) in the growth of the pathogen. Also, it will be worthwhile to evaluate the ability of the mutant strain to survive within an animal model. HupB certainly must play a role in vivo, as it is expressed in tuberculosis patients (11). In a recent study (23), we showed a statistically significant (P < 0.01) negative correlation of high levels of anti-HupB antibodies in tuberculosis patients with low serum iron status, implying that HupB is upregulated in the iron-limited environment of the human host. The in vivo expression of the protein coupled with the essentiality of this protein to survive in vivo points to the potential of HupB as a vaccine candidate.

In conclusion, this study has contributed to a better understanding of the iron acquisition machinery, particularly the role of HupB in iron homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S.D.P. and S.Y. acknowledge a Senior Research Fellowship by the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR; Government of India), and M.C. acknowledges a Senior Research Fellowship by the University Grants Commission (UGC; Government of India). A.R. acknowledges the Department of Biotechnology (DBT; Government of India), and M.S. acknowledges the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (DBT Centre of Excellence, BT/01/COE/07/02), for financial assistance and UGC-SAP & DBT-CREBB (Government of India) for infrastructural facilities. M.S. and S.D.P. acknowledge the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU), United Kingdom, for funding the research in the Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency (AHVLA; United Kingdom).

S.D.P. thanks Paul Golby (AHVLA, United Kingdom) for his help with molecular techniques.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 March 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01483-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ratledge C. 2004. Iron, mycobacteria and tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 84:110–130. 10.1016/j.tube.2003.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberg ED. 2003. The therapeutic potential of lactoferrin. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 12:841–851. 10.1517/13543784.12.5.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chipperfield JR, Ratledge C. 2000. Salicylic acid is not a bacterial siderophore: a theoretical study. Biometals 13:165–168. 10.1023/A:1009227206890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochan I. 1973. The role of iron in bacterial infections, with special consideration of host-tubercle bacillus interaction. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 60:1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratledge C, Dover LG. 2000. Iron metabolism in pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:881–941. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sritharan M. 2006. Iron and bacterial virulence. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 24:163–164 http://www.ijmm.org/text.asp?2006/24/3/163/26987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macham LP, Ratledge C, Nocton JC. 1975. Extracellular iron acquisition by mycobacteria: role of the exochelins and evidence against the participation of mycobactin. Infect. Immun. 12:1242–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quadri LE, Ratledge C. 2005. Iron metabolism in the tubercle bacillus and other mycobacteria, p 341–357 In Cole ST, Eisenach KD, McMurray DN, Jacobs WRJ. (ed), Tuberculosis and the tubercle bacillus. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quadri LE, Sello J, Keating TA, Weinreb PH, Walsh CT. 1998. Identification of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene cluster encoding the biosynthetic enzymes for assembly of the virulence-conferring siderophore mycobactin. Chem. Biol. 5:631–645. 10.1016/S1074-5521(98)90291-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Voss JJ, Rutter K, Schroeder BG, Su H, Zhu Y, Barry CE., III 2000. The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:1252–1257. 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeruva VC, Duggirala S, Lakshmi V, Kolarich D, Altmann F, Sritharan M. 2006. Identification and characterization of a major cell wall-associated iron-regulated envelope protein (Irep-28) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13:1137–1142. 10.1128/CVI.00125-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takatsuka M, Osada-Oka M, Satoh EF, Kitadokoro K, Nishiuchi Y, Niki M, Inoue M, Iwai K, Arakawa T, Shimoji Y, Ogura H, Kobayashi K, Rambukkana A, Matsumoto S. 2011. A histone-like protein of mycobacteria possesses ferritin superfamily protein-like activity and protects against DNA damage by Fenton reaction. PLoS One 6:e20985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sassetti C, Boyd D, Rubin E. 2001. Comprehensive identification of conditionally essential genes in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:12712–12717. 10.1073/pnas.231275498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratledge C, Ewing M. 1996. The occurrence of carboxymycobactin, the siderophore of pathogenic mycobacteria, as a second extracellular siderophore in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 142(Part 8):2207–2212. 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold B, Rodriguez GM, Marras SA, Pentecost M, Smith I. 2001. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis IdeR is a dual functional regulator that controls transcription of genes involved in iron acquisition, iron storage and survival in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 42:851–865. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar D, Nath L, Kamal MA, Varshney A, Jain A, Singh S, Rao KV. 2010. Genome-wide analysis of the host intracellular network that regulates survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell 140:731–743. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewin A, Baus D, Kamal E, Bon F, Kunisch R, Maurischat S, Adonopoulou M, Eich K. 2008. The mycobacterial DNA-binding protein 1 (MDP1) from Mycobacterium bovis BCG influences various growth characteristics. BMC Microbiol. 8:91. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goelz SE, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B. 1985. Purification of DNA from formaldehyde fixed and paraffin embedded human tissue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 130:118–126. 10.1016/0006-291X(85)90390-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez GM, Voskuil MI, Gold B, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. 2002. ideR, an essential gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of IdeR in iron-dependent gene expression, iron metabolism, and oxidative stress response. Infect. Immun. 70:3371–3381. 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3371-3381.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krithika R, Marathe U, Saxena P, Ansari MZ, Mohanty D, Gokhale RS. 2006. A genetic locus required for iron acquisition in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:2069–2074. 10.1073/pnas.0507924103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto S, Yukitake H, Furugen M, Matsuo T, Mineta T, Yamada T. 1999. Identification of a novel DNA-binding protein from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Microbiol. Immunol. 43:1027–1036. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegrist MS, Unnikrishnan M, McConnell MJ, Borowsky M, Cheng TY, Siddiqi N, Fortune SM, Moody DB, Rubin EJ. 2009. Mycobacterial Esx-3 is required for mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:18792–18797. 10.1073/pnas.0900589106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivakolundu S, Mannela UD, Jain S, Srikantam A, Peri S, Pandey SD, Sritharan M. 2013. Serum iron profile and ELISA-based detection of antibodies against the iron-regulated protein HupB of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in TB patients and household contacts in Hyderabad (Andhra Pradesh), India. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 107:43–50. 10.1093/trstmh/trs005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.