Abstract

Objectives. We evaluated associations between current asthma and birthplace among major racial/ethnic groups in the United States.

Methods. We used multivariate logistic regression methods to analyze data on 102 524 children and adolescents and 255 156 adults in the National Health Interview Survey (2001–2009).

Results. We found significantly higher prevalence (P < .05) of current asthma among children and adolescents (9.3% vs 5.1%) and adults (7.6% vs 4.7%) born in the 50 states and Washington, DC (US-born), than among those born elsewhere. These differences were among all age groups of non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics (excluding Puerto Ricans) and among Chinese adults. Non–US-born adults with 10 or more years of residency in the United States had higher odds of current asthma (odds ratio = 1.55; 95% confidence interval = 1.25, 1.93) than did those who arrived more recently. Findings suggested a similar trend among non–US-born children.

Conclusions. Current asthma status was positively associated with being born in the United States and with duration of residency in the United States. Among other contributing factors, changes in environment and acculturation may explain some of the differences in asthma prevalence.

Asthma affects an estimated 300 million persons globally, and in the United States, asthma prevalence increased 74% from 1980 to 1996.1,2 In 2009, an estimated 26.4 million persons (7.7% of adults and 9.6% of children) in the United States had asthma.3 Asthma is a disease of complex traits, with interactions between multiple genetic and environmental factors. Place of birth has often been associated with asthma. Studies on immigrants have shed light on the roles of environmental and acculturation factors in the development and exacerbation of asthma as well as in global variations in asthma prevalence.4–7 These findings are particularly relevant for a country such as the United States, where asthma prevalence is among the highest in the world and which saw a 22% increase in its foreign-born population from 2000 to 2008.8 Previous studies found higher asthma prevalence among Mexican American, Black, and Asian participants who were born in the United States than who were born elsewhere.4,6,9,10 Asthma prevalence differences within ethnicities between native- and foreign-born populations highlight the role of environment in the development and exacerbation of asthma.7 However, the extent to which these differences can be explained by access to health care, differential diagnostic practices, bias in self-reports, migration from a low- to a high-allergen area, or other social acculturation factors remains an area of active research.4,6,7,11–14

We comprehensively examined the association between current asthma and birthplace among other factors for all major racial/ethnic groups in the United States in 9 years (2001–2009) of nationally representative data from the National Health and Interview Survey.

METHODS

The National Health and Interview Survey is an in-person annual health survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States.15 A representative sample of households and noninstitutional group quarters (e.g., college dormitories) is included via multistage probability sampling.15 A randomly selected adult (aged ≥ 18 years) from each household is included in the Sample Adult Core file; an adult family member is selected as a proxy respondent for children and adolescents younger than 18 years in the Sample Child Core file.15 We analyzed data from the 2001 to 2009 surveys.

We based current asthma status on affirmative responses to both of the following questions: “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have asthma?” and “Do you still have asthma?” We classified respondents as either US-born (born in the 50 US states or Washington, DC) or non–US-born (born elsewhere) according to their reported place of birth. Although persons born in the US territories (e.g., Puerto Rico, Guam) are not immigrants to the United States, we considered place of birth to be a proxy reflecting different physical environment. We analyzed data for children and adolescents (aged < 18 years) and adults (aged ≥ 18 years) separately. We included age, health insurance coverage, home ownership status, and region of residence in the analysis. Poverty levels were calculated using ratio of income to federal poverty thresholds published by the US Census Bureau.16 Missing values were imputed using standard methods.17 Poverty levels were categorized as poor (≤ 0.99), near poor (1.00–1.99), or not poor (≥ 2.00).16 We included birth weight information (low birth weight defined as ≤ 2500 g) for children and adolescents. We also incorporated information on education level, smoking status, body mass index (defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters; ≤ 24.9 = normal or underweight, 25.0–29.9 = overweight, ≥ 30.0 = obese), usual source of medical care, and comorbidities (e.g., heart disease, emphysema, bronchitis) for adults.

We used logistic regression to determine the association between current asthma and birthplace. We collapsed some racial/ethnic categories in the children and adolescents’ multivariate analysis because of small numbers (n < 20) with current asthma. We developed additional stratum-specific models of US-born and non–US-born adults with a forward-selection approach to determine the association between sociodemographic factors, duration of US residency (< 10 years vs ≥ 10 years), and current asthma. We included age and gender in all models. We performed the chunk test to identify significant 2-way interactions. We reported model-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and prevalence estimates (i.e., predicted marginals) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We did not assess the association between duration of residency in the United States and current asthma among non–US-born children and adolescents because of the categorical nature of the residency duration data and lack of data in the higher-duration group (≥ 10 years) for younger age groups (e.g., ≤ 5 years). However, we reported the frequencies of residency duration categories for all age groups. We used SAS-Callable SUDAAN software (release 10.0, Research Triangle Institute, NC) to generate prevalence estimates. We considered estimates derived from fewer than 20 events in a single stratum unreliable and either did not report them or identified them where applicable. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design and data weights.15

RESULTS

Our sample comprised 102 524 children and adolescents and 255 156 adults; 2.5% of the children and adolescents and 15.5% of the adults were born outside the United States. A total of 9187 children and adolescents (8.9%) and 18 363 adults (7.1%) reported currently having asthma. The largest group (38.4%) of US-born and the majority (55.7%) of non–US-born children and adolescents with current asthma were aged 12 to 17 years (Table 1). Most adults with current asthma were aged 35 to 64 years. Most children and adolescents with current asthma were male, and most adults with current asthma were female. A higher proportion of non–US-born than US-born respondents with current asthma were poor or near poor, renters, and uninsured. More non–US-born than US-born children and adolescents with current asthma had had a low birth weight (20% vs 12.6%). Among adults with current asthma, a higher proportion of US-born than non–US-born participants had at least a high school diploma, were obese, were current smokers, had a usual place of medical care, and had at least 1 comorbidity (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of US Children and Adolescents and Adults With Current Asthma by Birthplace: National Health Interview Survey, 2001–2009

| Children and Adolescents (aged < 18 y; n = 9187) |

Adults (Aged ≥ 18 y; n = 18 363) |

|||

| Variable | US-Born, % | Non–US-Born, % | US-born, % | Non–US-Born, % |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 25.3 | 15.7 | … | … |

| 6–11 | 36.3 | 28.7 | … | … |

| 12–17 | 38.4 | 55.7 | … | … |

| 18–34 | … | … | 32.3 | 26.3 |

| 35–64 | … | … | 52.4 | 53.3 |

| ≥ 65 | … | … | 15.4 | 20.4 |

| Male gender | 58.9 | 56.0 | 35.3 | 37.8 |

| Poverty levela | ||||

| Poor | 23.7 | 29.8 | 16.6 | 22.6 |

| Near poor | 22.8 | 21.8 | 19.6 | 23.6 |

| Not poor | 53.5 | 48.4 | 63.8 | 53.9 |

| Home ownership | ||||

| Own | 62.2 | 52.8 | 67.3 | 54.5 |

| Rent | 28.3 | 38.6 | 27.4 | 35.0 |

| Rental assistance | 9.5 | 8.6 | 5.3 | 10.5 |

| Health insurance | 94.0 | 81.8 | 86.3 | 82.6 |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Northeast | 20.3 | 26.7 | 19.1 | 28.9 |

| Midwest | 25.3 | 11.3 | 26.8 | 12.5 |

| South | 36.0 | 42.3 | 33.5 | 25.5 |

| West | 18.4 | 19.7 | 20.7 | 33.1 |

| Low birth weightb | 12.6 | 20.0 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Some high school | … | … | 16.7 | 33.2 |

| ≥ high school diploma | … | … | 83.3 | 66.8 |

| Body mass indexc | ||||

| Normal or underweight | NA | NA | 33.1 | 33.9 |

| Overweight | NA | NA | 30.5 | 32.7 |

| Obese | NA | NA | 36.4 | 33.5 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current | NA | NA | 25.2 | 14.7 |

| Former | NA | NA | 24.4 | 20.8 |

| Never | NA | NA | 50.5 | 64.4 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| 0 | NA | NA | 34.3 | 39.6 |

| 1–2 | NA | NA | 42.1 | 39.3 |

| ≥ 3 | NA | NA | 23.6 | 21.1 |

| Usual place of medical cared | … | … | 90.9 | 87.4 |

| Residence in the United States, y | ||||

| < 10 | … | NA | … | 17.2 |

| ≥ 10 | … | NA | … | 82.9 |

Note. NA = data fully or partially not available for all categories or survey years; US-born = born in the 50 US states or Washington, DC. Ellipses indicate not applicable.

Ratio of income to US Census Bureau federal poverty level16 defined as poor (≤ 0.99), near poor (1.00–1.99), or not poor (≥ 2.00).

Defined as ≤ 2500 g.

Defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (≤ 24.9 = normal or underweight, 25.0–29.9 = overweight, ≥ 30.0 = obese).

Data for children and adolescents not included in the analysis.

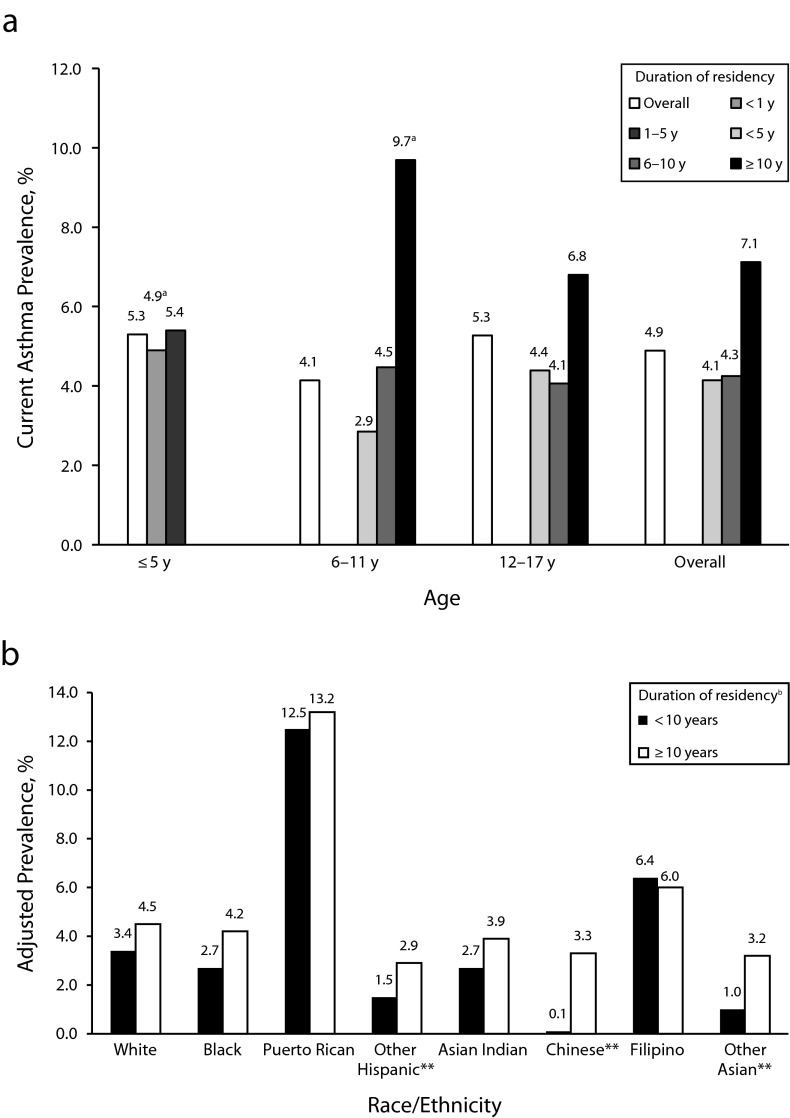

The adjusted current asthma prevalence was higher among US-born (9.3%) than non–US-born (5.1%) children and adolescents (P < .001). We observed a similar difference among adults (7.6% vs 4.7%). US-born White, Black, and Hispanic children and adolescents and adults and Chinese adults had higher prevalence of current asthma than their non–US-born counterparts (Figure 1; P < .05).

FIGURE 1—

Adjusted current asthma prevalence by race/ethnicity among US-born and non–US-born (a) children and adolescents (aged < 18 years) and (b) adults (aged ≥ 18 years): National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2001–2009.

Note. US-born = born in the 50 US states or Washington, DC. For children and adolescents, multivariate model adjusted for age, gender, poverty level, home ownership status of primary caregiver, low birth weight, region of residence, and birthplace, averaged over significant 2-way interactions between all variables in the model (other race category not included in the figure). For adults, multivariate model adjusted for age, gender, education level, poverty level, home ownership status, smoking status, body mass index, health insurance coverage, having a usual place of medical care, comorbidities, region of residence, and birthplace, averaged over significant 2-way interactions between birthplace, race/ethnicity and other variables. American Indian/Alaska Native and other race categories not included in the figure. The overall adjusted prevalence was (a) 9.3% for US-born and 5.1% for non–US-born (P < .001) and (b) 7.6% for US-born and 4.7% for non–US-born (P < .001)

aStatistically unreliable (unweighted n < 20).

*P < .05.

Hispanic adults (excluding Puerto Ricans) had lower odds of current asthma than non-Hispanic Whites (US-born, OR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.72, 0.88; non–US-born, OR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.58, 0.92), and Puerto Ricans had higher odds (US-born, OR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.40, 1.94; non–US-born, OR = 2.37; 95% CI = 1.86, 3.03). Non–US-born Filipino adults also had higher odds (OR = 1.58; 95% CI = 1.11, 2.24) than non–US-born Whites. In stratum-specific (US-born and non–US-born) multivariate models, for both US- and non–US-born adults being younger than 65 years, female, a renter, or obese or having at least 1 comorbid condition increased the odds of reporting current asthma (data not shown).

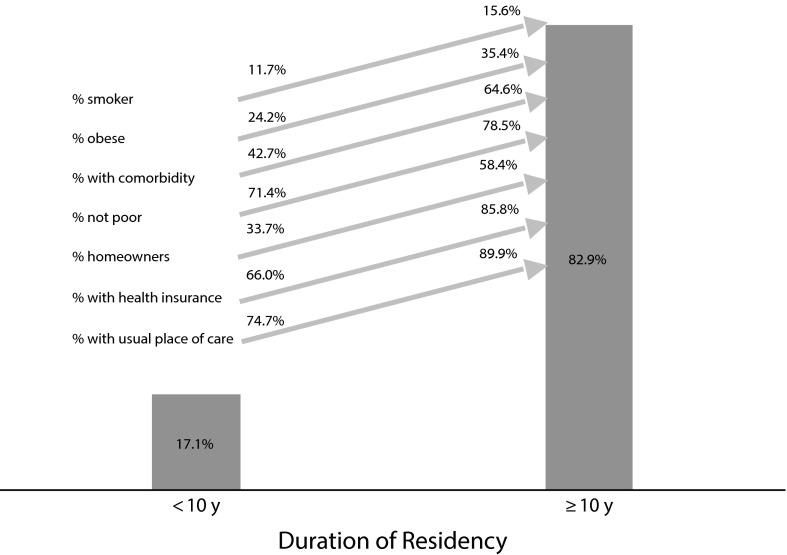

Non–US-born children and adolescents were more likely to have current asthma if they had resided in the United States for 10 years or more (Figure 2). We also observed a trend of increased current asthma prevalence with duration of residency in the younger age groups. In a multivariate model that included all the variables in Table 1, non–US-born adults who had resided in the United States for 10 years or more had higher odds of current asthma (OR = 1.55; 95% CI = 1.25, 1.93) than those who had arrived more recently (data not shown). This difference was significant among Hispanic, Chinese, and Asian persons (Figure 2). Most non–US-born adults with current asthma (82.9%) had resided in the United States for 10 years or more, and prevalences of smoking, obesity, comorbidity, home ownership, health insurance coverage, and having a usual place of medical care were also higher among this group (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2—

Current asthma prevalence among non–US-born (a) children and adolescents (aged < 18 years) by age and duration of US residency and (b) adults (aged ≥ 18 years) by race/ethnicity and duration of US residency: National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2001–2009.

Note. US-born = born in the 50 US states or Washington, DC. For adults, multivariate model adjusted for age, gender, poverty level, home ownership status, smoking status, body mass index, health insurance coverage, having a usual place of medical care, comorbidities, and region of residence. American Indian/Alaska Native and other race categories not included in the figure.

aMight be statistically inconsistent because of small sample size in the stratum.

bFor ≥ 10 years vs < 10 years residency, adjusted odds ratio = 1.55 (95% confidence interval = 1.25, 1.93).

**P < .001.

FIGURE 3—

Distribution of current asthma prevalence among non–US-born adults and changes in individual and sociodemographic factors with duration of US residency: National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2001–2009.

Note. US-born = born in the 50 US states or Washington, DC.

DISCUSSION

Asthma prevalence is higher in Westernized, economically developed countries than in developing countries.18,19 This global variation can be explained to some extent by differential level of exposure to environmental risk factors.6,20 Studies around the world have found lower rates of asthma, atopy, or respiratory symptoms among immigrants from developing countries.21–39 The sudden shift in micro and macro environments resulting from migration and changes in disease status and patterns among populations with similar genetic makeups might help identify environmental factors that are associated with or protective against asthma.40

Ours was the first study to incorporate all major US racial/ethnic groups in a large, nationally representative sample with a wide age span. Among our sample, non–US-born children and adolescents and adults had significantly lower asthma prevalence than their US-born counterparts, and this difference persisted after adjustment for a range of potential confounding variables. Multiple factors could play a role in driving this difference. On the whole, immigrants from developing countries have been found to have lower rates of asthma, heart disease, cancer, and other chronic diseases than the local population; this is known as the nativity effect.41–43 Migrants are also generally healthier than the population they left behind in their home countries, which is known as the healthy migrant effect.40,42,44,45 One study attributed a lower prevalence of childhood asthma in immigrant Turkish children in Germany to a selection bias: migrant parents were healthier than general population.28 Children born to healthy parents share a similar health advantage and are less likely to have a family history of atopy or allergic disease.21,25,31,37

The hygiene hypothesis postulates that in utero or early childhood microbial exposure protects against atopy and asthma. This protection might originate from individual, behavioral, and lifestyle factors such as rural location, early childhood infections, pet ownership, multiple siblings, day care attendance, and exposure to farm animals.46–57 Nearly 45% of immigrant Mexicans in the United States were reported to be from rural areas in Mexico.4 This protection conferred by nativity might gradually wane in the face of a host of new allergens, pollution, and other factors, because immigrants usually develop atopic and allergic disorders at rates similar to or higher than the host population several years after migration.21 Generally immigrants come from a country with low asthma prevalence,36,37 and their new environment may expose them not only to a high level of allergens, but also to new types of allergens. As a result, the disease status and the spectrum of allergy among immigrants changes over time and becomes similar to that of the local population.21,22,25,26,31,32,36 Mexican American children who lived in the United States the first year of their life or moved to the country before they reached 2 years of age were significantly more likely to have physician-diagnosed asthma than their peers who lived in Mexico for the first year or migrated at an older age.58,59 Hispanic children who were brought to the United States before entering first grade had a higher prevalence of allergy and current asthma than children who arrived later.60 Immigrant children have also been found to manifest asthma symptoms at a later age.25,31 In our sample, 55.7% of non–US-born children and adolescents and only 38.4% of US-born children and adolescents with current asthma were aged 12 to 17 years. By contrast, 15.7% of non–US-born and 25.3% of US-born minors with current asthma were 5 years old or younger. Although the environmental exposures these children experienced were not known, it is possible that early childhood exposure in the country of origin might have had some protective effect on children younger than 12 years. Also, immigrant children aged 5 years or younger might not have lived in the United States long enough for an adaptive immune response to a new environment to occur and asthma symptoms to manifest. Similar to adults, children and adolescents with longer US residency had higher reported current asthma prevalence. US-born children and adolescents had higher frequency of hay fever and respiratory allergy in the past 12 months than non–US-born children and adolescents, but this advantage decreased with longer residence in the country (data not shown).

Our findings suggest a possible role of acculturation in asthma. Among non–US-born adults, 68% to 99% of those with current asthma in different racial/ethnic groups had lived in the United States 10 years or longer. In a cohort of children in El Paso, Texas, Hispanic children from more acculturated families had higher a prevalence of asthma and allergy than those from less acculturated families.60 Changes in asthma status among Mexican American immigrants and an increase in asthma prevalence with residency duration in the United States have been associated with changes in protective dietary practices (e.g., consumption of fruits and vegetables).4 Similarly, Asian immigrants to Australia tend to replace their native low-salt, high-fiber diet of fish and vegetables with a less healthy Western diet that is high in salt and saturated fat.23 We found that US-born adults were more likely than their non–US-born counterparts to be obese, but obesity increased among non–US-born adults with current asthma with longer US residence. An increase in obesity was previously implicated in the increase of asthma prevalence among the migrant Mexican American population born in Mexico.4 We found that smoking also increased among non–US-born individuals with longer US residence. Increases in obesity and smoking suggest that behavior and lifestyle change over time, which may affect asthma status adversely.

Maternal asthma and pre- and postnatal exposures to tobacco have been associated with asthma and have been found to be differentially distributed among immigrant populations by degree of acculturation.61 Hispanic children from highly acculturated families had higher prevalence of maternal asthma and prenatal exposure to smoking than Hispanic families with low acculturation.62 In our study, the prevalence of current smoking was lower among non–US-born adults as a whole but higher among persons with current asthma and with longer US residency. Mothers of Mexican American children born in the United States were more likely than mothers whose children were born in Mexico to be smokers.61 However, differences in asthma prevalence by birthplace among children persist even after accounting for the effects of smoking exposure.4,6 Our results were consistent with this finding. Increases in smoking among non–US-born adults with duration of residency suggest that the probability of non–US-born children being exposed to secondhand smoke from smoking parents, guardians, or relatives is likely to increase with longer residence in the United States.

Access to health care, differential diagnostic practices, and health care–seeking behavior might explain some differences between US- and Mexican-born Mexican Americans because immigrants who had lived in the United States for 10 years or longer were more likely to have a usual place of medical care.4 In our study, fewer non–US-born than US-born children and adolescents and adults had health insurance coverage, and more non–US-born adults reported not having a usual place of care. However, among non–US-born adults who had lived in the country 10 years or more, the proportions with health insurance and a usual place of care were similar to those of US-born adults. Differences in current asthma prevalence remained after adjusting for these factors. This suggests that health care access or reporting bias could account for some of the observed heterogeneity but could not explain it all. Previous studies have reported that low asthma prevalence among immigrant populations might not be explained by health care access issues6,44,63 or diagnostic bias.6 However, whether either a change in health care–seeking behavior or perception of wheezing occurs over time, resulting in relatively higher asthma prevalence in long-term immigrants, needs to be investigated further.4,7

Current asthma prevalence was also highest among long-term immigrants (Figure 3). Members of this group had higher socioeconomic status but were more likely to be obese, to smoke, and to have comorbidities. The increase of both favorable and unfavorable factors with duration of residency might result in ambidirectional changes in risk, and some individual and social factors may have more influence on asthma status than others and may more amenable to intervention. For example, increases in smoking and obesity with duration of US residence suggest that public health programs might usefully focus on smoking cessation and healthier lifestyle interventions among early immigrants.

The differences in current asthma prevalence between US- and non–US-born respondents were not consistent among all racial/ethnic groups. Non–US-born Hispanic children and adolescents and adults had significantly lower asthma prevalence than US-born Hispanics and Whites. Hispanics are known to experience favorable health outcomes despite adverse socioeconomic status—a phenomenon known as the Hispanic epidemiological paradox.42,43,64 However, Hispanic subgroups with different backgrounds might not have a similar advantage in avoiding asthma.44,65,66 Puerto Rican children and adults had the highest asthma prevalence61,65–68 and the highest asthma mortality rate7,69 among all racial/ethnic groups. In our study, non–US-born and US-born Puerto Rican participants had similar asthma prevalence. Puerto Ricans in our sample also had higher levels of education, home ownership, health insurance coverage, and usual place of care than other Hispanics but were more likely to be smokers and to have at least 1 comorbid condition (data not shown). Higher asthma prevalence among Puerto Ricans has previously been attributed to certain biological, social, and environmental factors, but the exact cause remains poorly understood.67,68 Puerto Ricans also maintain close ties with their home communities and travel there periodically; this may lead to commonalities in exposures (e.g., allergens, microbial agents, air pollutants) and behaviors (e.g., smoking, eating, physical activity) both on the island and on the mainland.70 Similarly, factors specific to each racial/ethnic group might explain the difference or lack of difference among US- and non–US-born residents.

Limitations

Our data were cross-sectional, which limited our ability to draw any conclusions about causality because of uncertain temporal direction and other issues. The use of birthplace as a proxy for immigration status or migration into a different physical environment might be problematic. Persons born in the US territories and some western European countries might have experienced physical environments or lifestyles similar to those of people born in the United States. In addition, short-term immigrants differ from long-term immigrants in region of residence, occupation, and socioeconomic status, possibly leading to different indoor and outdoor environmental exposures and levels of adaptation that were not captured in cross-sectional data.4,7,32

Many important variables, such as family history of atopy, actual exposure to indoor and outdoor allergens, outdoor traffic and air pollution, and treatment received were not available in our data. Data were self-reported and therefore subject to recall or reporting bias. However, the direction and magnitude of recall bias, if present, could not be ascertained. Ideally, longitudinal data with comprehensive family and exposure history and with accurate tracking of environmental and acculturation changes might be the most appropriate mechanism to understand disease development and exacerbation.7,42

Our data on asthma prevalence should be interpreted in the context of differential diagnostic practices and difficulty in diagnosing asthma in very young children and among the elderly. However, a sensitivity analysis that excluded children aged 5 years and younger and adults aged 65 years and older did not yield significant differences in current asthma prevalence by place of birth.

Language barriers and cultural beliefs might lead to differential understanding, reporting, and diagnoses, because many epidemiological studies are self-reported.36,40,42 Some African languages have no word for asthma.40 Lower prevalence of asthma and wheezing among recent immigrants to Italy was attributed to underreporting of symptoms, among other factors.36,40 Mexican American mothers with low acculturation were less likely to report asthma than highly acculturated Hispanic, European American, or Black mothers.61 Belief systems specific to particular cultures might inhibit reporting of socially undesirable outcomes (e.g., asthma) or overly immodest status (e.g., excellent health).45,61 Our data did not allow us to explore this issue further. However, a study that relied on multilingual questionnaires to assess asthma and asthma symptoms independently of the effects of cultural variation in language reported that the observed differences were not likely attributable to differential reporting.63,71,72

Conclusions

It is difficult, if not impossible, to explain the recent rapid increase of asthma prevalence globally by genetic factors alone.46 Among other factors, environmental exposures and acculturation in developed countries might influence asthma outcomes in a cumulative and time-dependent manner that could result in spatial and temporal heterogeneity among immigrant groups. Assessing asthma prevalence in communities with large non–US-born populations without accounting for nativity might result in incomplete understanding of the asthma burden that may subsequently affect public health prevention strategies.10 However, heterogeneity among immigrant populations might not be explained by 1 or 2 environmental or acculturation factors. A host of genetic, individual, environmental, and acculturation factors, and the interplay among them, need to be considered.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required because the study used secondary, deidentified, publicly available data.

References

- 1.Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130(1 suppl):4S–12S. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Gwynn C, Redd SC. Surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: asthma prevalence, disease characteristics, and self-management education—United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(17):547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holguin F, Mannino DM, Antó J et al. Country of birth as a risk factor for asthma among Mexican Americans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):103–108. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-143OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Country of birth, acculturation status and abdominal obesity in a national sample of Mexican-American women and men. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(3):470–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eldeirawi K, McConnell R, Freels S, Persky VW. Associations of place of birth with asthma and wheezing in Mexican American children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold DR, Acevedo-Garcia D. Immigration to the United States and acculturation as risk factors for asthma and allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(1):38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Migration Policy Institute. The United States: social and demographic characteristics. Available at: http://www.migrationinformation.org/datahub/state.cfm?ID=US. Accessed July 15, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brugge D, Lee AC, Woodin M, Rioux C. Native and foreign born as predictors of pediatric asthma in an Asian immigrant population: a cross sectional survey. Environ Health. 2007;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brugge D, Woodin M, Schuch TJ, Salas FL, Bennett A, Osgood ND. Community-level data suggest that asthma prevalence varies between U.S. and foreign-born Black subpopulations. J Asthma. 2008;45(9):785–789. doi: 10.1080/02770900802179957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drake KA, Galanter JM, Burchard EG. Race, ethnicity and social class and the complex etiologies of asthma. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(4):453–462. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.4.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum E. Racial/ethnic differences in asthma prevalence: the role of housing and neighborhood environments. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49(2):131–145. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold DR, Wright R. Population disparities in asthma. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen RT, Celedón JC. Asthma in Hispanics in the United States. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27(3):401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Health Interview Survey: research for the 1995–2004 redesign. Vital Health Stat 2. 1999;Jul(126):1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics. Survey Description Document, National Health Interview Survey, 2007. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenker N, Raghunathan TE, Chiu PL, Makuc DM, Zhang G, Cohen AJ. Multiple imputation of missing income data in the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Stat Assoc. 2006;101(475):924–933. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beasley R International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. World-wide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjuctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351(9111):1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai CK, Beasley R, Crane J, Foliaki S, Shah J, Weiland S International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Three Study Group. Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. 2009;64(6):476–483. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.106609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Netuveli G, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A. Ethnic variations in incidence of asthma episodes in England & Wales: national study of 502,482 patients in primary care. Respir Res. 2005;6:120. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rottem M, Szyper-Kravitz M, Shoenfeld Y. Atopy and asthma in migrants. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;136(2):198–204. doi: 10.1159/000083894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg R, Vinker S, Zakut H, Kizner F, Nakar S, Kitai E. An unusually high prevalence of asthma in Ethiopian immigrants to Israel. Fam Med. 1999;31(4):276–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung R. Asthma and migration. Respirology. 1996;1(2):123–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.1996.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson PG, Henry RL, Shah S, Powell H, Wang H. Migration to a western country increases asthma symptoms but not eosinophilic airway inflammation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36(3):209–215. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung RC, Carlin JB, Burdon JG, Czamy D. Asthma, allergy, and atopy in Asian immigrants in Melbourne. Med J Aust. 1994;161(7):418–425. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1994.tb127522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell CV, Nolan TM, Carlin JB, Bennett CM, Johnson PD. Respiratory symptoms and duration of residence in immigrant teenagers living in Melbourne, Australia. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81(2):159–162. doi: 10.1136/adc.81.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang HY, Wong GW, Chen YZ et al. Prevalence of asthma among Chinese adolescents living in Canada and in China. CMAJ. 2008;179(11):1133–1142. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabesch M, Schaal W, Nicolai T, Mutius E. Lower prevalence of asthma and atopy in Turkish children living in Germany. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(3):577–582. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13357799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalyoncu AF, Stalenheim G. Survey on the allergic status in a Turkish population in Sweden. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 1993;21(1):11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grüber C, Illi S, Plieth A, Sommerfeld C, Wahn U. Cultural adaptation is associated with atopy and wheezing among children of Turkish origin living in Germany. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32(4):526–531. doi: 10.1046/j.0954-7894.2002.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Partridge MR, Gibson GJ, Pride NB. Asthma in Asian immigrants. Clin Allergy. 9(5):489–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1979.tb02513.x. 197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalyoncu AF, Stålenheim G. Serum IgE levels and allergic spectra in immigrants to Sweden. Allergy. 1992;47(4 pt 1):277–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1992.tb02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tedeschi A, Barcella M, Bo GA, Miadonna A. Onset of allergy and asthma symptoms in extra-European immigrants to Milan, Italy: possible role of environmental factors. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):449–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lombardi C, Penagos M, Senna G, Cannonica GW, Passalacqua G. The clinical characteristics of respiratory allergy in immigrants in northern Italy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2008;147(3):231–234. doi: 10.1159/000142046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ventura MT, Munno G, Giannoccaro F et al. Allergy, asthma and markers of infections among Albanian migrants to Southern Italy. Allergy. 2004;59(6):632–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Migliore E, Pearce N, Bugiani M et al. SIDRIA-2 Collaborative Group. Prevalence of respiratory symptoms in migrant children to Italy: the results of SIDRIA-2 study. Allergy. 2007;62(3):293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcon A, Cazzoletti L, Rava M et al. Incidence of respiratory and allergic symptoms in Italian and immigrant children. Respir Med. 2011;105(2):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lombardi C, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G IGRAM, Italian Group on Respiratory Allergy in Migrants. The possible influence of the environment on respiratory allergy: a survey on immigrants to Italy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(5):407–411. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burastero SE, Masciulli A, Villa AM. Early onset of allergic rhinitis and asthma in recent extra-European immigrants to Milan, Italy: the perspective of a non-governmental organisation. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2011;39(4):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalyoncu AF. Symptoms of asthma, bronchial responsiveness and atopy in immigrants and emigrants in Europe. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(5):980–981. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00305302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anikeeva O, Bi P, Hiller JE, Ryan P, Roder D, Han GS. The health status of migrants in Australia: a review. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22(2):159–193. doi: 10.1177/1010539509358193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huh J, Prause JA, Dooley CD. The impact of nativity on chronic diseases, self-rated health and comorbidity status of Asian and Hispanic immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(2):103–118. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, LeClere FB. Race/ethnicity, nativity, and US adult mortality (statistical data included) Soc Sci Q. 1999;780:136–153. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Subramanian SV, Jun HJ, Kawachi I, Wright RJ. Contribution of race/ethnicity and country of origin to variations in lifetime reported asthma: evidence for a nativity advantage. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):690–697. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pernice R. Methodological issues in research with refugees and immigrants. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1994;25(3):207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Douwes J, Pearce N. Asthma and the westernization “package.”. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6):1098–1102. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holt PG, Sly PD, Björkstén B. Atopic versus infectious diseases in childhood: a question of balance? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1997;8(2):53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1997.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez FD, Holt PG. Role of microbial burden in aetiology of allergy and asthma. Lancet. 1999;354(suppl 2):SII12–SII15. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)90437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene and household size. BMJ. 1989;299(6710):1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strachan DP. Allergy and family size: a riddle worth solving. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27(3):235–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krämer U, Heinrich J, Wjst M, Wichmann HE. Age of entry to day nursery and allergy in later childhood. Lancet. 1999;353(9151):450–454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ball TM, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Griffith KA, Holberg CJ, Martinez FD, Wright AL. Siblings, day care attendance, and the risk of asthma and wheezing during childhood. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(8):538–543. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez FD. Role of viral infections in the inception of asthma and allergies during childhood: could they be protective? Thorax. 1994;49(12):1189–1191. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.12.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S et al. Early childhood infectious diseases and the development of asthma up to school age: a birth cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):390–395. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gereda JE, Leung DYM, Thatayatikom A et al. Relation between house-dust endotoxin exposure, type 1 T-cell development, and allergen sensitisation in infants at high risk of asthma. Lancet. 2000;355(9216):1680–1683. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Svanes C, Jarvis D, Chinn S, Burney P. Childhood environment and adult atopy: results from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(3 pt 1):415–420. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hesselmar B, Aberg N, Aberg B, Eriksson-B, Björkstén B. Does early exposure to cat or dog protect against allergy development? Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29(5):611–617. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Eldeirawi K, McConnell R, Furner S et al. Associations of doctor-diagnosed asthma with immigration status, age at immigration, and length of residence in the United States in a sample of Mexican American school children in Chicago. J Asthma. 2009;46(8):796–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eldeirawi KM, Persky VW. Associations of physician-diagnosed asthma with country of residence in the first year of life and other immigration-related factors: Chicago asthma school study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99(3):236–243. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60659-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Svendsen ER, Gonzales M, Ross M, Neas LM. Variability in childhood allergy and asthma across ethnicity, language, and residency duration in El Paso, Texas: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2009;8:55. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klinnert MD, Price MR, Liu AH, Robinson JL. Unraveling the ecology of risks for early childhood asthma among ethnically diverse families in the Southwest. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):792–798. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eldeirawi KM, Persky VW. Associations of acculturation and country of birth with asthma and wheezing in Mexican American youths. J Asthma. 2006;43(4):279–286. doi: 10.1080/0277090060022869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Litt JS, Goss C, Diao L et al. Housing environments and child health conditions among recent Mexican immigrant families: a population-based study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(5):617–625. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wei M, Valdez RA, Mitchell BD, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP. Migration status, socioeconomic status, and mortality rates in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites: the San Antonio Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(4):307–313. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lara M, Akinbami L, Flores G, Morgenstern H. Heterogeneity of childhood asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican children bear a disproportionate burden. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):43–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA et al. National surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980 – 2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007;56(8):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mendoza FS, Ventura SJ, Valdez RB et al. Selected measures of health status for Mexican-American, mainland Puerto Rican, and Cuban-American children. JAMA. 1991;265(2):227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lara M, Morgenstern H, Duran N, Brook RH. Elevated asthma morbidity in Puerto Rican children: a review of possible risk and prognostic factors. West J Med. 1999;170(2):75–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Homa DM, Mannino DM, Lara M. Asthma mortality in US Hispanics of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban heritage, 1990–1995. Am J Respir Crit Care. 2000;161(2 pt 1):504–509. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9906025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Plant J, Keating HJ., III Puerto Rican patients to Puerto Rico: assessing the effect on clinical care. Conn Med. 1997;61(11):713–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galant SP, Crawford LJ, Morphew T, Jones CA, Bassin S. Predictive value of a cross-cultural asthma case-detection tool in an elementary school population. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e307–e316. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0575-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sunyer J, Basagnaña X, Burney P, Anto JM. International assessment of the internal consistency of respiratory symptoms. European Community Respiratory Health Study (ECRHS) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3 pt 1):930–935. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9911062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]