Abstract

In Chile, workers are mandated to choose either public or private health insurance coverage. Although private insurance premiums depend on health risk, public insurance premiums are solely linked to income. This structure implies that individuals with higher health risks may tend to avoid private insurance, leaving the public insurance system responsible for their care. This article attempts to explore the determinants of health insurance selection (private vs public) by individuals in Chile and to test empirically whether adverse selection indeed exists. We use panel data from Chile’s ‘Encuesta de Proteccion Social’ survey, which allows us to control for a rich set of individual observed and unobserved characteristics using both a cross-sectional analysis and fixed-effect methods. Results suggest that age, sex, job type, income quintile and self-reported health are the most important factors in explaining the type of insurance selected by individuals. Asymmetry in insurance mobility caused by restrictions on pre-existing conditions may explain why specific illnesses have an unambiguous relationship with insurance selection. Empirical evidence tends to indicate that some sorting by health risk and income levels takes place in Chile. In addition, by covering a less healthy population with higher utilization of general health consultations, the public insurance system may be incurring disproportionate expenses. Results suggest that if decreasing segmentation and unequal access to health services are important policy objectives, special emphasis should be placed on asymmetries in the premium structure and inter-system mobility within the health care system. Preliminary analysis of the impact of the ‘Garantias Explicitas de Salud’ plan (explicit guarantees on health care plan) on insurance selection is also considered.

Keywords: Health insurance, adverse selection, public/private

KEY MESSAGES.

The structure of health insurance premiums in Chile, which is linked to health risk in the private system and to income in the public system, may imply that individuals with higher health risks may tend to prefer the public insurance system, possibly affecting its financial sustainability.

This article uses panel data, which allows us to control for a rich set of individual observed and unobserved characteristics, to explore the determinants of health insurance selection in Chile, using both a cross-sectional analysis and fixed-effect methods.

Results confirm that some sorting by health risk and income levels takes place in Chile as age, sex, job type, income quintile and self-reported health appear to be the most important factors in explaining insurance selection by individuals.

Evidence on health insurance selection and switching patterns presented in this study suggests that when decreasing segmentation and unequal access to health services are important policy objectives, special emphasis should be placed on making the premium structure of public insurance more symmetric and in improving inter-system mobility.

Introduction

In many countries, private health insurance co-exists with public health insurance. Private insurance may provide either principal or supplementary coverage to their population, and participation in it is often voluntary. In addition, private health insurance premiums tend to depend on health risk, whereas public insurance premiums often depend solely on income (Savedoff and Sekhri 2004). Consequently, if private insurance charges higher rates for less healthy people, then these individuals may tend to avoid private insurance, leaving the public system responsible for their care. If so, the public health system may incur higher health expenditures for providing care to the less healthy population, an issue of concern for policymakers charged with the financial sustainability of publicly provided health services.

In Chile, workers and pensioners are required to purchase employment-based health insurance, and may choose either public or private coverage. The public system is known as ‘Fondo Nacional de Salud’ (FONASA), and the private system is composed of a number of private insurers known as ‘Instituciones de Salud Previsional’ (ISAPRE). While the insurance premium in the private system depends on basic health risk indicators, the premium for public coverage depends exclusively on one’s salary. In particular, the public health insurance premium is 7% of an individual’s salary, regardless of any health indicator or publicly available information on age, sex and the number of dependents. At the same time, public insurance provides a single fixed standard benefits package that does not change with income. That is, the quality of the benefits package does not improve as the premium in the public system increases.

In addition, public insurance may completely or partially cover the enrollee and his or her family’s out-of-pocket medical costs. Eligibility is based on the household’s income and family structure, but not on risk characteristics. Moreover, public insurance automatically covers the unemployed and very low-income individuals. The public system, however, relies on public hospitals (and some associated private facilities), which are sometimes associated with longer wait times, higher variability in quality and more stringent restrictions on the locations where care may be obtained.

In contrast, private insurance plans typically include more benefits as the premium increases, and premiums are based on the insured individual’s and his or her dependents’ health risk. Although the premiums are set by the insurer, they are directly linked to a ‘table of factors’ that captures the ‘relative values for each enrollee as a function of whether the person is the head of the family or a dependent, sex and age’ (Sanchez and Munoz 2008) and the level of coverage. Private plans typically provide access to better technology, faster service and more alternatives with respect to facilities and doctors, though more expensive, in particular for more serious health conditions (Henriquez 2006). Unlike the public system, individuals must report all pre-existing conditions before enrolling in private plans. Failure to do so may imply the denial of partial or complete coverage.

As a result of Chile’s health insurance structure, those with higher income are more likely to select a private plan simply because they can get more for their money, whereas those who have higher health risks may be more likely to choose public health insurance due to usually lower out-of-pocket medical costs. Thus, the structure of Chile’s health insurance industry tends to favour the accumulation of riskier and poorer individuals in the public system, a phenomenon called ‘segmentation’.

In addition, the asymmetry in mobility between systems due to the fact that individuals can switch freely to the public system but with certain restrictions back to the private system may favour strategic behaviour. For instance, people may purchase private insurance for outpatient treatment when healthy and switch to the public system when costlier treatment is needed. That is, healthy individuals may purchase private insurance for outpatient treatment only, while holding the public system as free insurance against more serious illnesses (Sapelli and Torche 2001). It is worth noting, however, that changes in legislation over the last decade have prevented individuals from enrolling in both systems simultaneously. That is, individuals now ‘can only make sequential use of both insurance policies’ (Kifmann 1998).

The article’s objective is to explore the determinants behind households’ health insurance decisions (public or private). In addition, we try to test empirically the hypothesis that the public health system in Chile serves more high risk individuals, controlling for a rich set of individual characteristics, using panel data from the ‘Encuesta de Proteccion Social’ (EPS) survey for 2004 and 2006.1

‘Segmentation’, or the fact that the structure of Chile’s health care system implies that riskier and poorer individuals tend to self-select into the public system, has been an important subject of study and a priority policy objective for Chilean authorities for more than a decade. The ‘Garantias Explicitas de Salud’ (GES) plan2 is a set of guarantees included in Chile’s health care reforms that began to be implemented in 2003 whose main purpose is to transform health care in Chile into a better, more efficient and more equitable social protection system. The plan offers guarantees in terms of minimum coverage and quality, maximum waiting time and, with some restrictions, maximum out-of-pocket costs for certain medical conditions.

Prior to implementation, the expected direction of change in mobility between systems implied by these reforms is ambiguous. For instance, the guarantee that private plans cannot offer less coverage than the public system may attract higher-risk individuals to the private system but, at the same time, may discourage low-risk individuals to purchase private plans as they are now required to pay for coverage they do not need. In addition, given a particular income level, new guarantees in quality, waiting time and possible lower out-of-pocket medical costs make the public system relatively more attractive without increases in premiums. On the other hand, guarantees in coverage for certain medical conditions and caps on out-of-pocket costs, which, all else equal, would make the private sector more attractive, are likely to be accompanied with higher premiums (though a ‘compensation fund’ that subsidizes insurers enrolling riskier individuals is expected to partially alleviate this effect). Dawes (2010) finds that, though the reform does ease ‘segmentation’ in Chile’s health care, the net result is that the plan increases the likelihood for an average person to choose public insurance. We do not expect the reform to show major impacts on the probability for an individual to choose either system in 2004 and 2006, given that this plan began to be gradually introduced only in mid-2005. However, we will discuss the possible influence of the reform on our findings.

Results show that household size, age, some measures of health risk, income levels and job types are significant factors associated with health insurance selection in Chile, given the current structure of the health system. In particular, larger families tend to select public insurance due to its decreasing premium per household member; young workers tend to move towards the private system, whereas retirees tend to move in the opposite direction; individuals with higher incomes are more likely to select private insurance, being self-employed is linked to a higher likelihood of having public insurance due to the disconnection between income and health benefits; and having good to excellent self-rated health status and exercising frequently are significantly associated with having private insurance. In addition, some changes in the odds of selecting private insurance between 2004 and 2006 can be seen consistent with the impact of the GES plan on insurance selection in Chile. That is, though too early to consider the changes in the marginal effects of some variables as consequences of the reform, they seem to provide some preliminary evidence of possible changes.

With respect to the panel analysis, changes in health status and insurance selection show fewer robust relationships, perhaps due to the asymmetry in insurance mobility in Chile caused by the existence of pre-existing condition restrictions. By comparing the estimates from a cross-sectional regression to those using fixed effects, we can consider whether cross-sectional estimates may be misleading due to omitted variable bias.3

Other studies have attempted to confirm such prediction for the Chilean health care system. For instance, using a simple theoretical model and cross-sectional data from the ‘Encuesta de Caracterizacion Socioeconomica Nacional’ (CASEN) survey,4 Sapelli and Torche (2001) show that the very structure of the health insurance system favours adverse selection against the public programme. However, their model includes no health risk indicators apart from age and sex and relies on cross-sectional data. Sanhueza and Ruiz-Tagle (2002) also use CASEN data to examine the determinants of insurance choice in Chile. By placing special emphasis on the endogeneity of this choice with respect to expected service utilization, the authors identify selection bias as a result of individuals’ private information on their health risks. Likewise, Henriquez (2006) estimates the determinants that jointly affect both health insurance selection and health care utilization decisions using a large set of explanatory variables. He finds that factors such as age, gender, marital status, education, income and employment status are important in explaining insurance choice.

While the previous literature on insurance choice in the Chilean health system has highlighted issues of adverse selection and health insurance, they rely almost exclusively on cross-sectional data. However, with panel data, we can control for unobserved characteristics that may affect this decision. For example, knowledge of healthy habits could lead to individuals both choosing private insurance (perhaps for a better benefits package) and taking fewer health risks. Individual characteristics affecting the outcome variables that are not observed (and therefore captured in the error term) may be correlated with observed characteristics (included in the model as regressors) and cause simple estimates to be biased. We believe that controlling for an important array of individual observed and unobserved characteristics over time constitutes our article’s main contribution.

Evidence on health insurance selection and switching patterns such as the one found in this study must be considered for policies aiming to further reform the health care system in Chile and other countries. For instance, if segmentation and unequal access to health services are important issues for policymakers, special emphasis should be placed on asymmetries in the premium structure of the health care system, asymmetries in inter-system mobility and the financial sustainability of publicly provided health services.

Conceptual framework

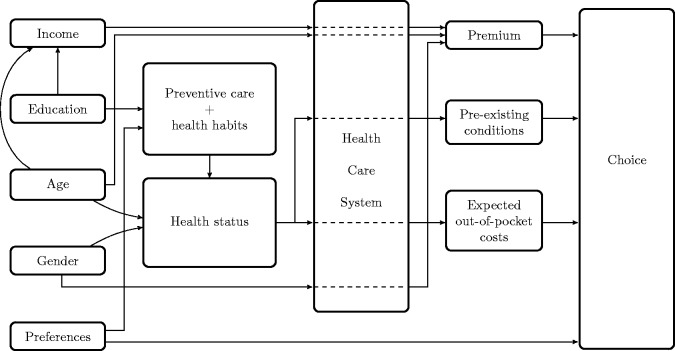

Figure 1 shows the relevant factors behind our model’s choice of health insurance by individuals within the Chilean health care system. There are demand, supply and regulation factors, and with the exception of preferences, they interact with one another to determine this choice. For instance, the health care structure in Chile implies that people’s income affects premiums for both systems but corresponding increases in benefits take place only in the private system. Therefore, higher income tends to favour private insurance.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

In our model, education affects decisions through two channels. More years of schooling tend to increase income, and so premiums.5 Furthermore, higher education is also correlated with decisions on preventive care and health habits (such as exercising, drinking, smoking and so on), which in turn are factors that contribute to determining health status.6 People’s health conditions interact with the health care structure by, first, determining the expected out-of-pocket cost of treatments, which may substantially differ between systems and second, if qualifying conditions were contracted outside the private system, they could be considered pre-existing conditions and individuals may only have access to the public system.

Age affects insurance choice through several paths. For instance, age and health status are directly correlated. For that reason, age also affects premiums, though only in the private system. Therefore, the probability of choosing private insurance decreases as individuals age. In addition, age tends to positively affect income due to its correlation with labour experience. Gender may also affect people’s choices through its impact on health status and premiums. Females, all else equal, tend to present higher observed morbidity rates.7 The structure of the health care system is also crucial in that female enrollees pay higher premiums in the private system but not in the public system. Therefore, all else equal, females should have a lower probability of choosing private insurance than males.

Finally, preferences may influence insurance decisions through both their impact on people’s lifestyle and preventive care decisions, and simply due to different subjective tastes towards either system. In our model, preferences are considered as an unobservable variable.

Data and methods

The EPS survey, conducted nationwide in Chile, in 2004 and 2006, follows a panel of individuals over time. The survey includes questions on health and insurance status at each point in time, as well as household demographic characteristics, labour market status, income and extensive information on participation and knowledge of the country’s private pension programme. The combined panel for this analysis consists of 18 474 distinct individuals, of whom there are observations for both years for 14 696 individuals. Table 1 shows a list of the insurance status of the entire sample.

Table 1.

Insurance status, EPS 2004 and 2006

| 2004 |

2006 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | % | Observations | % | |

| Public | 12 614 | 75.4 | 12 852 | 78.2 |

| Private | 2134 | 12.8 | 2018 | 12.3 |

| None | 1472 | 8.8 | 953 | 5.8 |

| Other | 507 | 3 | 620 | 3.8 |

| Total | 16 727 | 100 | 16 443 | 100 |

In the following analysis, we limit the sample to those who have either private or public insurance and, thus, we exclude individuals who report having either no insurance (‘none’) or ‘other’ insurance. We justify this decision due to the fact that, first, health insurance in Chile is mandatory and second, the option ‘other’ corresponds to health insurance plans provided by the armed forces and police exclusively to their members. Therefore, the only relevant alternatives of health insurance for the civilian population are the public provider or any of the private insurers. Consequently, removing these observations should not produce biased results. Table A1 presents descriptive statistics for the sample of individuals with public or private insurance.

The methodological approach to the article is as follows. To examine characteristics correlated with having private health insurance, we first conduct logistic regressions on cross-sectional data for 2004 and 2006. Using the logistic approach, we can explore what characteristics may be associated with the ‘odds’ of having private insurance (priv) as opposed to public insurance (pub) in a cross-sectional framework. The logit model of the probability that an individual i would choose private takes the form:

| (1) |

where X is a vector of demographic and socioeconomic variables that are hypothesized to affect the insurance choice, and  for

for  are the vectors of the unknown parameters associated with each of vector X's elements. Equation (1) can be re-written as the following logit equation to be estimated:

are the vectors of the unknown parameters associated with each of vector X's elements. Equation (1) can be re-written as the following logit equation to be estimated:

| (2) |

where  is the dichotomous dependent variable that takes the value of 1 when the household chooses private insurance, and 0 otherwise,

is the dichotomous dependent variable that takes the value of 1 when the household chooses private insurance, and 0 otherwise,  is the individual error term, and n is the number of explanatory variables that include the household’s demographic and socioeconomic variables (such as size, income, education, gender, marital status, location, employment situation and so on) and health-related variables (such as self-assessed health status, health behaviour, weight category and having being diagnosed some chronic or severe illnesses).

is the individual error term, and n is the number of explanatory variables that include the household’s demographic and socioeconomic variables (such as size, income, education, gender, marital status, location, employment situation and so on) and health-related variables (such as self-assessed health status, health behaviour, weight category and having being diagnosed some chronic or severe illnesses).

Next, to see what factors may be relevant for changes from public to private insurance (or vice versa) over that period, we conduct a logistic regression with ‘fixed effects’ using the pooled data. Fixed effects allow us to control for factors that are unobserved, such as individual preferences, and other characteristics that are important for the determination of health insurance choice, but that are effectively time-invariant. Consequently, the fixed-effect approach focuses on the explanatory power of changes in the data on the change of an explanatory variable over time and, by controlling for unobserved characteristics, the use of the fixed-effects approach allows us to reduce omitted-variable bias.

The econometric specification is similar to Equation (2) with the addition of the time subscript t in the variables and the error term:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where  captures the time-invariant unobserved characteristics associated to household i that affect insurance selection, and

captures the time-invariant unobserved characteristics associated to household i that affect insurance selection, and  is a time-variant error term.

is a time-variant error term.

Results

Cross-sectional estimates

Table 2 shows the results of the cross-sectional logistic analysis for 2004 and 2006. Overall, measures of income, wealth and having higher status jobs are associated with private insurance selection, as expected. In particular, higher incomes are linked to increased odds of having private insurance for both years. Unlike in the private system, as individuals pay a fixed percentage of their salaries for health insurance in the public system, premiums increase with income without a corresponding improvement in the benefits package. That is, private plans may offer more for the money. Note that the odds of choosing private increase in 2006 for some quintiles but not for others. This result is consistent with the fact that the implementation of the GES plan is ambiguous with regard to the expected direction of change in the selection of health insurance.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of private health insurance on regressors

| 2004 |

2006 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio |  |

Odds ratio |  |

|

| Ages 25–44 | 1.515 | 0.000 | 1.174 | 0.231 |

| Ages 45–64 | 1.924 | 0.000 | 1.635 | 0.001 |

| Ages 65 or older | 0.845 | 0.322 | 0.688 | 0.045 |

| Female | 0.687 | 0.000 | 0.730 | 0.000 |

| Completed education = 12 years | 0.145 | 0.000 | 0.098 | 0.000 |

Completed education  12 years 12 years |

0.430 | 0.000 | 0.325 | 0.000 |

| Married/cohabitating | 1.191 | 0.009 | 1.405 | 0.000 |

| Household size | 0.827 | 0.000 | 0.821 | 0.000 |

| Urban | 1.845 | 0.000 | 1.552 | 0.000 |

| Own home | 1.232 | 0.004 | 1.458 | 0.000 |

| Self-employed | 0.382 | 0.000 | 0.472 | 0.000 |

| Domestic worker | 0.278 | 0.001 | 0.092 | 0.000 |

| Unemployed | 0.567 | 0.000 | 0.514 | 0.000 |

| Not in labour force | 1.099 | 0.278 | 0.906 | 0.272 |

| Income quintile 2 | 1.229 | 0.200 | 2.481 | 0.000 |

| Income quintile 3 | 2.057 | 0.000 | 7.052 | 0.000 |

| Income quintile 4 | 3.720 | 0.000 | 14.93 | 0.000 |

| Income quintile 5 | 11.107 | 0.000 | 9.091 | 0.000 |

| Health status poor | 0.730 | 0.172 | 0.691 | 0.063 |

| Health status good to excellent | 1.583 | 0.000 | 1.491 | 0.000 |

| Any activities of daily living (ADL) | 0.706 | 0.129 | 0.704 | 0.032 |

| Medium to heavy smoker | 0.941 | 0.408 | 0.967 | 0.690 |

| Heavy drinker | 0.938 | 0.408 | 0.956 | 0.551 |

| Frequent exercise | 0.931 | 0.386 | 0.962 | 0.645 |

| Diagnosed arthritis | 1.164 | 0.354 | 0.817 | 0.222 |

| Diagnosed stroke | 1.102 | 0.889 | 0.870 | 0.832 |

| Diagnosed cancer | 1.138 | 0.633 | 1.242 | 0.378 |

| Diagnosed cardiovascular disease | 0.962 | 0.833 | 0.940 | 0.720 |

| Diagnosed depression | 0.951 | 0.695 | 0.932 | 0.553 |

| Diagnosed diabetes | 0.723 | 0.065 | 0.937 | 0.663 |

| Diagnosed high blood pressure | 0.798 | 0.027 | 0.873 | 0.158 |

| Diagnosed mental illness | 0.126 | 0.052 | 0.809 | 0.663 |

| Diagnosed asthma/emphysema | 0.935 | 0.730 | 1.328 | 0.083 |

| Diagnosed renal disease | 1.075 | 0.738 | 0.842 | 0.468 |

| Disabled | 0.496 | 0.001 | 0.861 | 0.357 |

Underweight ( ) ) |

1.042 | 0.893 | 1.009 | 0.978 |

| Overweight (BMI 25–30) | 1.090 | 0.183 | 1.036 | 0.583 |

Obese ( ) ) |

0.876 | 0.169 | 1.047 | 0.609 |

| Log likelihood | −3868.6 | −4028.6 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.326 | 0.306 | ||

Similarly, owning one’s home and living in the Santiago metropolitan area are also associated with higher odds of having private insurance. Equity in housing is a major component of household wealth in Chile [in our sample, more than 75% of households own their property in 2006, which is consistent with the 70% cited by Torche and Spilerman (2006) for 2000]. The observed steady increase in housing prices over the last decade has created important gains in household wealth among homeowners. Parrado et al. (2009) find a high correlation between housing value and disposable income in Chile during the period 2002–7. Therefore, it is not surprising that home ownership is associated with the selection of private health insurance. In addition, the availability of health care providers in Chile is much larger in urban zones than in rural areas. In fact, the only health providers available in most rural areas are state-provided public hospitals (Sanhueza and Ruiz-Tagle 2002). Therefore, the benefit of having private health insurance in rural areas is much lower than in urban zones, where most of the private networks are concentrated. Consequently, one would expect a strong correlation between location and insurance selection.

On the other hand, being a domestic worker or unemployed is associated with lower odds of having private insurance when compared with public and private employees. Domestic workers tend to have lower incomes and are often hired without a formal contract. Though workers without formal contracts are less likely to participate in programmes linked to employment, such as health insurance or pension programmes, health insurance coverage in Chile is almost full given that health insurance in Chile is universal and guaranteed for all workers through the public system (FONASA). In fact, 94% of domestic workers are reported to have health benefits, most of them through FONASA (Tokman 2010), which in addition automatically covers individuals with no income, including the unemployed.

Being self-employed is also associated with lower odds of having private insurance. Self-employment in Chile, as in most of the developing world, is also linked to lower incomes and less participation in social protection programmes. Puentes et al. (2007), for instance, find that most self-employed individuals in developing economies work informal jobs that offer ‘no social security, severance pay, minimum wage or working condition standards’. In fact, Bravo et al. (2010) show that <10% of self-employed workers in Chile could be considered high-skilled. In addition, self-employment tends to be riskier than salaried employment. Pardo and Ruiz-Tagle (2011), for instance, show that the standard deviation of income for self-employed workers in Chile is significantly higher than for salaried workers. Given the health insurance premium is linked to a standard benefits package in the public system, regardless of one’s income, the higher variability of income linked to self-employment may lead workers in this sector to choose public insurance more often. The introduction of the GES plan, however, implies a drastic reduction in the variety of plans offered by private insurers (and the possibility that they can be modified in the future). Therefore, the drop in the uncertainty over the coverage included in private plans may attract self-employed individuals towards the private system. The finding that the odds of choosing private for self-employed workers increase in 2006 relative to 2004 is consistent with this contention.

The expected impact of family size on insurance selection is clear ex ante. Given that FONASA’s premium structure is independent from the household’s socioeconomic status (including its size), the higher the number of dependents, the more attractive the public system is in terms of premium cost per member. As expected, we find a strong negative correlation between family size and the odds of private insurance selection.

Cross-sectional results show somewhat unclear associations between poorer health and private insurance selection. For instance, data show that individuals diagnosed with some illnesses that might qualify as pre-existing conditions, such as mental illness or disability, are significantly less likely to have private insurance in 2004 but not in 2006. In contrast, individuals diagnosed with asthma or emphysema have higher odds of having private insurance in 2006 but not in 2004. These results are consistent with the fact that mobility between the private and public system in Chile is asymmetric. Illnesses that qualify as pre-existing conditions may prevent individuals from being covered by private insurers if the illness was diagnosed prior to entry into the private system. Therefore, several conflicting forces come into play. On one hand, individuals in worse health may tend to accumulate in the public health system, as mobility from public to private is limited. On the other hand, workers in the private system may maintain private coverage, even if, in an unrestricted scenario, they might optimally choose to move to the public system, due to the fear that unforeseen negative future health shocks may prevent them from ever switching back (Pardo and Schott 2012). In addition, there is an adverse selection problem. Individuals who expect to have those diseases may choose to switch to (or remain in) the private sector due to its potentially better coverage and access to newer technology. At the same time, however, for serious health conditions requiring expensive treatment, the public system may become more appealing due to its lower out-of-pocket cost (Henriquez 2006). In addition, the GES plan guarantees coverage in the private system of several conditions that formerly were absent from cheaper private plans. While greater coverage may increase the odds that individuals with those conditions select private insurance, results suggest little evidence of this scenario. Therefore, there is no unambiguous reason that an individual with worse health would ex ante tend to prefer one system or the other.

Obesity is a primary health-risk indicator, as people who are obese are more likely to contract conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, elevated blood pressure, high cholesterol, coronary artery disease, strokes and so on later in life (Raman 2002). Sturm and Wells (2001) found that chronic conditions and out-of-pocket medical care costs are more closely linked to obesity than to more conventional risk behaviours such as smoking or drinking. The choice of public vs private health insurance is ambiguous for households with obese individuals in Chile. On one hand, selection of private insurance may secure access to better quality services later in life. On the other hand, obese individuals may prefer the public system, as treatments tend to be less expensive. Ex ante, we do not anticipate a clear correlation between obesity and insurance selection. The cross-sectional results suggest that obese individuals have lower odds of having private health insurance in the 2004 cross-section, while there is no significant link in 2006. The same rationale applies to other health behaviour factors, such as heavy smoking, heavy drinking, low exercise frequency or being over- or underweight. We do not find significant correlations between private insurance and these health behaviours.

Studies in many countries have found that females, all else equal, tend to present higher observed morbidity than men (though, lower mortality rates). Case and Paxson (2005), for instance, confirm the hypothesis that differences towards worse self-rated health in women can be entirely explained by sex differences in the distribution of health conditions. Therefore, women may be inclined to select public insurance due to its lower medical costs. Our results show that, in fact, females have lower odds of having private insurance in both samples.

With respect to age, while health risk increases with age (increasing the likelihood of choosing public), individuals tend to earn more as they get older, due to the correlation between age and labour experience (increasing the likelihood of choosing private). Pardo and Schott (2012) find that age is significantly associated with insurance selection through three mechanisms: lower health status at older ages, higher private premiums at older ages and higher incomes (and, thus, higher public premiums) at older ages. Income and health risk effects are already accounted for by other variables, thus the only effect that is left is the effect of age on premium. In fact, in our findings, individuals aged 25–65 have higher odds of private insurance, whereas those individuals older than 65 have lower odds of private insurance. The drop in the odds of choosing private for individuals aged 45–65 is consistent with the general trend observed with the implementation of the health reform.

The most significant health risk variable in the cross-sectional analysis is self-reported health status. In both years, reporting good to excellent general health status is significantly associated with private insurance status. In the 2006 data, having poor self-rated health is associated with decreased odds of having private health insurance. In addition, note that there is a significant drop in the odds that individuals with good to excellent health status select private plans in 2006 vs 2004. This finding is consistent with the fact that the reform eliminated cheap outpatient-only private plans that were usually preferred by people with good health. The effective increase in premium in private plans may have influenced some to select the potentially cheaper public system.

In summary, in the cross-section, holding health risk constant, individuals in higher income quintiles are more likely to participate in private insurance programmes, possibly due to the direct income-to-premium-to-health-coverage link in the private system. Similarly, larger households are strongly linked to the public insurance due to this system’s complete disconnection between the number of dependents and premiums. However, we see varied results by health risk, and the most likely explanation is related to the asymmetry in mobility between health systems by individuals. While individuals can freely move from the private system to the public system, the reverse direction is much more restricted due to the existence of pre-existing condition clauses. Consequently, depending on health status expectations and the current system, individuals may choose to move or stay in either system to avoid higher costs (premiums and/or medical costs) or enjoy better services. Individuals appear to prefer the private system in their productive years, and then the public system when they retire (as raises in private premiums become more relevant). Finally, the variables for health status in the cross-section with the most significance are self-reported health status and sex. Given that the GES plan is quite new, evidence on its impact on insurance selection is far from conclusive. Nevertheless, some changes in the odds of selecting private insurance may be possibly attributed to the reform, such as those for self-employed, middle-aged and healthy individuals.

Panel data and fixed-effects estimates

To examine the relationship between the regressors and a change in insurance status from public to private or vice versa, we run a fixed-effects logit regression.8 As there are so few cases of individuals with changes in insurance status that are likely to have particular diseases, we grouped all individual diagnoses into one dummy variable for having been diagnosed with any of the illnesses.

Few of the individual characteristics that appear important in cross-sectional estimates maintain significance in fixed-effects estimates (table 3). This result is not surprising, as we are focusing on factors influencing a change in insurance choice, and in Chile, loyalty to one’s current system is fairly high (Sanchez 2005). From our sample, we observe slightly more than 2% of people enrolled changing from public in 2004 to private in 2006, while ∼20% moved in the opposite direction, making it more difficult for differences to have statistical significance. However, we find that several variables are significant in the fixed-effects model. The age category of between 25 and 44 years old, when most individuals are in the early-to-mid stages of their careers and in good health, is significantly associated with higher odds of switching to a private insurer, while being 65 or older, when most have retired and health status usually worsens, is associated with switching to the public system. Given that the marginal effects of income and health status are captured by other variables, the impact of age on selection goes solely through private premiums, which increase with age.

Table 3.

Logistic regression of private insurance status with fixed effects

| Odds ratio |  |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 25–44 | 1.868 | 0.088 | ||

| Ages 45–64 | 0.883 | 0.828 | ||

| Ages 65 or older | 0.149 | 0.142 | ||

| Married/cohabitating | 0.864 | 0.563 | ||

| Household size | 0.976 | 0.707 | ||

| Urban | 2.367 | 0.338 | ||

| Own home | 1.302 | 0.204 | ||

| Self-employed | 0.480 | 0.009 | ||

| Domestic worker | 0.000 | 0.977 | ||

| Unemployed | 0.705 | 0.189 | ||

| Not in labour force | 0.854 | 0.568 | ||

| Income quintile 2 | 0.734 | 0.379 | ||

| Income quintile 3 | 1.139 | 0.688 | ||

| Income quintile 4 | 1.821 | 0.058 | ||

| Income quintile 5 | 1.507 | 0.190 | ||

| Health status poor | 1.104 | 0.869 | ||

| Health status good to excellent | 1.574 | 0.044 | ||

| Any activities of daily living (ADL) | 0.915 | 0.855 | ||

| Medium to heavy smoker | 1.192 | 0.414 | ||

| Heavy drinker | 1.081 | 0.682 | ||

| Frequent exercise | 1.681 | 0.011 | ||

| Diagnosed any illness | 1.069 | 0.760 | ||

| Disabled | 1.179 | 0.742 | ||

Underweight ( ) ) |

5.185 | 0.151 | ||

| Overweight (BMI 25–30) | 1.879 | 0.002 | ||

Obese ( ) ) |

1.366 | 0.317 | ||

| Log likelihood | −360.8 | |||

Not surprisingly, income and income variability continue to be important. Being in the fourth income quintile is significantly associated with changes to private insurance status. This suggests that individuals in the first three quintiles tend to stay in the public system, whereas individuals in the fifth quintile tend to remain in the private system, leaving the fourth quintile as the most dynamic one. Similarly, being self-employed also continues to be significantly associated with lower odds of having private insurance.

While certain health risk factors are significant in cross-sectional estimates, very few are significant in describing the variation in changes from private to public insurance (or vice versa) from 2004 to 2006. Two health risk factors imply adverse selection into public insurance at a significant confidence level: individuals who exercise frequently have 68% higher odds of being enrolled in private insurance, and those who describe themselves as having good to excellent general health have 57% higher odds of having private insurance.

Having been diagnosed with a specific illness, having a disability, having difficulty with activities of daily living, being a heavy smoker or drinker or being obese are not significant in explaining moves to private insurance. However, it appears that being overweight (and to lesser extent, underweight) is associated with higher odds of private insurance status. This association, in principle, seems not to support the hypothesis of adverse selection for public insurance on the basis of body mass index (BMI) as a risk factor. However, as explained earlier, some of the conditions mentioned earlier may qualify as pre-existing conditions or be linked to illnesses that can be contracted later in life that do qualify as pre-existing conditions. Consequently, even if, in an unrestricted scenario, some individuals would optimally choose to move to one system or the other, in reality some of them may be ‘captive’ to their systems. Due to a current pre-existing condition, an individual may not be able to switch from the public system to a private insurer, and those who are in the private system and worry about getting ill in the future may not want to switch to the public system for fear of not being able return to private insurance if their conditions worsen and become pre-existing. Pardo and Schott (2012), for instance, predict that an elimination of restrictions on pre-existing conditions would imply movements of individuals between systems in both directions. In particular, those who switch to the private sector tend to have worse health and those who switch to the public insurer tend to have good health.

Overall, the fixed-effects approach allows us to control for relevant time-invariant, unobserved individual characteristics and thus minimize omitted variable bias. In particular, evidence of changes in health status contributing to adverse selection for public insurance in the 2-year time horizon is not as strong as suggested by cross-sectional estimates, implying that the simple cross-sectional estimates may be overestimated. In addition, having had a specific disease diagnosis or needing assistance with activities of daily living are not significant in this model. However, the lack of statistical significance could also be due to the asymmetry in insurance mobility in Chile caused by the existence of restrictions on pre-existing conditions. Nonetheless, having good to excellent self-reported health status is associated with switching to private insurance, and maintains almost the same level across all estimates, signalling some degree of adverse selection for public insurance.

Health behavioural factors, such as drinking and smoking, are not significant in any of the models, though exercising frequently becomes important in the fixed-effects estimates. In addition, being between the ages of 25 and 44 is significantly associated with switching to a private insurer, while being 65 or older is somewhat linked to the opposite movement. This model also suggests that the fourth income quintile is the most dynamic in terms of mobility from the public to the private sector.

Interestingly, the EPS survey asks individuals who change insurance provider the reason behind changes. Table 4 shows the reasons behind their decisions.

Table 4.

Top four reasons for changing health insurance type

| Type of change | Top four reasons | Per cent reporting reason |

|---|---|---|

| Public to private | Improved plan for the same premium | 32 |

| Some other reason | 22 | |

| Prefer the private health system | 18 | |

| Income increased | 15 | |

| Private to public | Health plan premium increased | 22 |

| Became unemployed | 21 | |

| Prefer the public health system | 21 | |

| Some other reason | 21 |

These answers point to the importance of price and income in affecting an individual’s choice of type of insurance, as well as the importance of personal preference. Presumably, reasons related to the quality of services would be included in a person’s preference, so we may suggest that access to and quality of services could be important. The fixed-effect method has a relative advantage to the cross-sectional approach in this framework, as it accounts for relevant unobserved individual characteristics, such as preferences.

Based on regression results and survey answers, we can suggest that income (and, to some extent, age and job status) and having good to excellent self-rated health status may be robust explanatory factors in insurance switching.

Concluding remarks

Comparing the estimates from a cross-sectional regression to that of a regression using fixed effects allows us to consider whether cross-sectional estimates may be misleading. Were we to have examined only cross-sectional estimates, we would have concluded that having specific diseases or disability is significant in explaining insurance status. Indeed, ordinary least squares estimates from the cross-sectional data might lead one to conclude there is a strong case for adverse selection for public insurance. However, the importance of some variables goes away with fixed-effects estimates, suggesting that the cross-sectional estimates may be biased due to unobserved heterogeneity or omitted variable bias. At the same time, as movement between systems is limited by pre-existing conditions, it may be that the lack of significance of particular diseases in predicting movement between systems reflects that these pre-existing conditions bind individuals to their current insurance programme.

Only a few characteristics, including age, good to excellent health status, being self-employed and being in a high income quintile, are significant in models both using cross-sectional and panel data. In particular, young workers tend to switch to private insurance, and older individuals tend to switch to public insurance. Having good to excellent health status maintains its significance in the fixed-effects model. Therefore, the fixed-effects model confirms the cross-sectional finding that the private insurance system indeed serves a more healthy population, suggesting that there is indeed adverse selection for public insurance.

Being self-employed, which is associated with less stability in income and linked to a lower likelihood of having private insurance, maintains significance and magnitude in both analyses. In both the cross-sectional and the panel estimates, at least one income quintile is significant, suggesting that indeed the public insurance system serves a less wealthy population. Again, these findings confirm the hypothesis of segmentation, or that the public system serves a less healthy and wealthy population.

While fixed-effect estimates are more consistent than cross-sectional estimates, the relatively short time horizon may be a limitation for the analysis of type of insurance selected, since only variables that change are relevant to the analysis. In addition, for some individual characteristics, such as sex, that do not change over time but are bound to have a significant relationship with insurance type, dependable estimates must rely on the cross-sectional approach.

Overall, this analysis provides evidence that some sorting by health risk and income levels may well take place in Chile, given the current structure of the health system. Such evidence should be considered in the design of policies aimed at further reforming the health system in Chile and other countries. If decreasing segmentation and improving access to health services are important policy objectives, special emphasis should be placed on asymmetries in the premium structure of the health care system and imbalanced mobility across systems. Though there is some preliminary evidence that the GES plan has eased segmentation in Chile, our findings also point to an increase in the probability that a person would choose public insurance under the new health reforms. This outcome raises questions about the financial consequences of the GES plan and of any policy changes affecting publicly provided health services.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Development at the National Institutes of Health (grant number HD007242).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Appendix

Table A1.

Variable means, individuals with public or private insurance, EPS 2004 and 2006

| 2004 |

2006 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Private insurance* | 14.5% | 13.6% | ||

| Female | 51.1% | 51.2% | ||

| Age** | 46.25 | 16.3 | 47.46 | 15.6 |

Schooling  years** years** |

56.5% | 54.7% | ||

Schooling  years** years** |

23.3% | 24.9% | ||

Schooling  years years |

19.9% | 20.4% | ||

| Married/cohabitating* | 61.7% | 63.0% | ||

| Household size | 4.08 | 1.8 | 4.08 | 1.9 |

| Santiago residence | 38.5% | 38.2% | ||

| Own home** | 78.1% | 75.5% | ||

| Self-employed** | 12.4% | 13.9% | ||

| Domestic worker* | 3.20% | 2.70% | ||

| Unemployed* | 9.50% | 10.4% | ||

| Not in labour force** | 32.1% | 29.4% | ||

| Health status poor* | 8.60% | 9.40% | ||

| Health status good+ | 63.5% | 63.0% | ||

| Any Activities of daily living (ADL)** | 6.90% | 10.4% | ||

| Medium to heavy smoker** | 18.9% | 12.2% | ||

| Heavy drinker | 19.2% | 19.7% | ||

| Frequent exercise | 13.3% | 12.6% | ||

| Diagnosed arthritis* | 6.50% | 7.10% | ||

| Diagnosed stroke | 0.40% | 0.40% | ||

| Diagnosed cancer | 1.50% | 1.70% | ||

| Diagnosed Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)** | 5.50% | 6.30% | ||

| Diagnosed depression** | 7.40% | 9.70% | ||

| Diagnosed diabetes** | 6.00% | 7.10% | ||

| Diagnosed HIV | 0.00% | 0.00% | ||

| Diagnosed high blood pressure** | 18.8% | 21.5% | ||

| Diagnosed mental illness | 0.70% | 0.70% | ||

| Diagnosed asthma/emphysema* | 3.80% | 4.30% | ||

| Diagnosed renal disease | 2.60% | 2.70% | ||

| Diagnosed any illness** | 34.8% | 37.3% | ||

| Disabled** | 8.90% | 9.90% | ||

Underweight ( )* )*

|

1.30% | 1.10% | ||

Overweight (BMI  )** )** |

39.4% | 42.4% | ||

Obese ( )* )*

|

16.7% | 17.7% | ||

| Number of general health consultations, last 2 years | 2.31 | 5.8 | 3.02 | 6.2 |

| Number of specialist visits, last 2 years | 2.01 | 5.7 | 2.18 | 5.7 |

| Number of emergency visits, last 2 years | 0.55 | 2.9 | 0.90 | 3.7 |

| Number of surgeries, last 2 years | 0.07 | 0.4 | 0.11 | 0.5 |

| Number of hospitalizations, last 2 years | 0.13 | 0.7 | 0.18 | 0.8 |

* and ** means significantly different at 5 and 1% margins of error, respectively.

Endnotes

Footnotes

1 Social protection survey.

2 Explicit health guarantees that was formerly known as ‘Plan de Acceso Universal de Garantias Explicitas’ (Plan AUGE).

3 Note that since we have two waves of data, it is possible to analyse only one instance of changes in health insurance. Therefore, the analysis of the impact of the GES plan on changes in health insurance over time is limited to the cross-sectional approach only.

4 National socioeconomic characterization survey.

5 Earning tend to systematically vary across individuals and over time due to differences in human capital accumulation, as given by schooling and experience. See Mincer (1974).

6 As in Ross and Wu (1995) and Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2006), education can be linked to health both directly (more educated people tend to be more informed and therefore take better care of themselves) and indirectly (more education implies more income and, thus, more preventive medical care, since health care is a normal good).

7 See, for instance, Verbrugge (1985).

8 A Hausman test suggests that fixed-effects estimates are more appropriate than random effects estimates, despite any efficiency gains from random effects.

References

- Bravo D, Ruiz-Tagle J, Vasquez J. Caracterizacion y participation de los trabajadores independientes en el sistema de pensiones chileno. 2010. Working Paper, Centro de Microdatos, Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Paxson C. Sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Demography. 2005;42:189–214. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence. 2006. Working Paper 12352, Cambridge Massachusetts, USA: NBER. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes A. 2010. Health care reform and its effect on the choice between public and private health insurance: evidence from Chile. Master in Economics Thesis, PUC Economics Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Henriquez R. Private health insurance and utilization of health services in Chile. Applied Economics. 2006;38:423–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kifmann M. Private health insurance in Chile: basic or complementary insurance for outpatient services? International Social Security Review. 1998;51:137–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer JA. Schooling, Experience, and Earnings. New York, USA: Columbia University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo C, Ruiz-Tagle J. The Dynamic Role of Specific Experience in the Selection of Self-Employment versus Wage-Employment. 2011. Working Paper, Chile: Mimeo, Centro de Microdatos, Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo C, Schott W. Public versus private: evidence on health insurance selection. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics. 2012;12:39–61. doi: 10.1007/s10754-012-9105-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado E, Cox P, Fuenzalida M. El sector inmobiliario chileno. Economa Chilena. 2009;12:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes E, Contreras D, Sanhueza C. Self-employment in Chile, long run trends and education and age structures changes. Estudios de Economia. 2007;34:203–47. [Google Scholar]

- Raman RP. Obesity and health risks. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2002;21:134S–9S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Wu C-L. The links between education and health. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:719–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M. Migracion de Afiliados en el Sistema Isapre. 2005. Working Paper, Superintendencia de Salud, Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M, Munoz A. Producto y Precios en el Sistema ISAPRE. 2008. Working Paper, Superintendencia de Salud, Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza R, Ruiz-Tagle J. Choosing health insurance in a dual health care system: the Chilean case. Journal of Applied Economics. 2002;V:157–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sapelli C, Torche A. The mandatory health insurance system in Chile: explaining the choice between public and private insurance. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics. 2001;1:97–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1012886810415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savedoff W, Sekhri N. Private Health Insurance: Implications for Developing Countries. 2004. Discussion paper no. 3-2004, World Health Organization, Geneva. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Wells K. Does obesity contribute as much to morbidity as poverty or smoking? Public Health. 2001;115:229–35. doi: 10.1038/sj/ph/1900764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokman V. Domestic Workers in Latin America: Statistics for New Policies. 2010. Working Paper 17, Cambridge, MA, USA: WIEGO. [Google Scholar]

- Torche F, Spilerman S. Household Wealth in Latin America. 2006. Working Papers RP2006/114, Helsinki, Finland: World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNU-WIDER) [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM. Gender and health: an update on hypotheses and evidence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1985;26:156–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]