Abstract

Objectives:

To investigate national trends in percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement for hospitalized elderly patients from 1993to 2003.

Methods:

Retrospective analysis of patients ≥65 years of age with PEG tube placement from 1993 to 2003 from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was utilized to calculate PEG placement rates per 1000 people.

Results:

Placement of PEG tube increased by 38% in elderly patients during the study period, from 2.71 procedures during hospitalization per 1000 people to 3.75 procedures during hospitalization per 1,000 people. Placement of PEG tube in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia doubled (5%-10%) over the study period.

Conclusion:

Over a 10-year period, PEG tube use in hospitalized elderly patients increased significantly. More importantly, approximately 1 in 10 PEG tube placements occurred in patients with dementia.

Keywords: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube, elderly, dementia

Background

Since its introduction in the early 1980s, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes are increasingly being placed among the elderly individuals as an alternative to nasogastric tubes and surgically placed gastrostomy tubes. While only 15 000 PEG tubes were placed in 1989, its placement frequency had increased significantly to 216 000 tubes by the year 2000, 1 and this trend is projected to continue 2 especially in elderly patients with cognitive impairment.

Cognitive impairment affects more than 5 million Americans and is projected to increase to 13.2 million by the year 2050. It is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among the elderly individuals. 3,4 Elderly patients with advanced dementia frequently develop feeding problems 5,6 related to memory loss, indifference/resistance to food intake, and failure to appropriately coordinate chewing and swallowing of the food bolus. Placement of PEG tube is increasingly being advocated in these patients to provide nutrition, hydration, and to administer medications with the long-term goal of improving quality of life and life span. Nationally, the prevalence of PEG tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment is high (18%-34%), 7 –9 and approximately 30% of these tubes are placed annually in patients with dementia. 10 However, despite widespread use, benefits associated with PEG placed in patients with dementia or significant cognitive impairment (SCI) remain unclear. 11 –14

In this study, we investigated temporal trends in the use of PEG tube among the elderly individuals with dementia, in the United States using a large national administrative database.

Research Design and Methods

Data source

This study was based on a retrospective analysis of data obtained from 10 years (1993-2003) of hospital discharge data using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 15 The HCUP family of databases is derived from a partnership between the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and statewide data organizations. The NIS includes 100% of discharges for all age groups and all payers from each sampled hospital. It contains data from approximately 1000 hospitals and includes 7 to 8 million hospital discharges annually. The NIS data are available from 1988 to 2003, which allows analysis of trends over time. However, fewer states participated prior to 1993 and could reduce the ability to capture rare conditions. In 1988, eight states were included in the NIS, representing approximately 30% of the US population. By 2005, 38 states were included, representing approximately 90% of the US population. 15 –18

The database contains information related to diagnosis and procedure codes, hospital length of stay, insurance status, median household income for the patient’s zip code of residence, and patient disposition including in-hospital death. Hospital-level data such as teaching status, ownership, region of the country, and hospital size also are included. The database contains weights for constructing national estimates and requires attention to the complex survey design to obtain correct standard errors. Complex survey design refers to nationally representative databases typically created by the Federal government. Observations are sampled in a specific manner and failure to account for this sampling leads to imprecise standard errors where everything would be significantly different. The NIS sampling frame permits the development of national estimates of incidence, in-hospital mortality, and information on disease trends. The NIS data are publicly available and are exempt from human participants review.

Study Population

All patients 65 years of age or older with a primary or secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedure code for PEG tube placement were included in the study. Rates per 1000 people were calculated using current population statistics. We calculated the number of elderly individuals in each year from the current population statistics and the number of hospitalizations involving a PEG tube from the NIS in each year to allow the calculation of rates. Patients were classified according to presence of several comorbid conditions, including Alzheimer’s dementia using their primary and secondary ICD-9-Clinical Modification (CM) diagnosis codes. The ICD-9 codes have been used in prior studies and were consistently followed. There was no evidence that they changed over the study period. Hospitalizations involving a transfer to another acute care hospital (pretransfer hospitalizations) were not included in the analysis in order to prevent double counting of the included participants. 19 Those participants were captured in the subsequent hospitalization at the receiving hospital.

Statistical Analysis

The HCUP database generates nationally representative estimates of inpatient hospitalizations when appropriately weighted. Statistical analyses using the weighting variables require the use of Stata software programs that is capable of accommodating the complex survey design to obtain appropriate standard errors. Significance testing was based on t tests for continual variables and chi-square statistics for dichotomous variables. All analyses were performed using the survey command suite in Stata statistical software (Version 9; College Station, Texas).

Results

Patient demographic characteristics subdivided by 2 periods (1993-1997 and 1998-2003) are presented in Table 1. The data were split into 2 time periods to assess whether there was any difference between the 5-year period before and after Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) in 1997. In-hospital mortality rates remained constant during the study period at approximately 12%, and no differences were noted between the 2 periods. More elderly patients were hospitalized from the emergency room in the 1998 to 2003 period compared to those in the 1993 to 1997 period (62.6% vs 55.2%; P < .001). The patient length of hospital stay (LOS) was significantly higher in the earlier period as compared to the 1998 to 2003 cohort (21 days vs 18.4 days; P < .001).

Table 1.

Characteristics in Hospitalizations With a Procedure Code of PEG Tube Among the Elderly Patients by Era From 1993 to 2003

| Variable | 1993-1997 | 1998-2003 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 80.2 | 80.1 | .086 |

| Female (%) | 56.3 | 54.9 | <.001 |

| Race (%) | |||

| Black | 17.0 | 18.0 | .223 |

| White | 74.2 | 68.8 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 5.9 | 7.9 | .004 |

| Other | 2.8 | 5.3 | <.001 |

| Admit source (%) | |||

| ED | 55.2 | 62.6 | <.001 |

| Transfer (hospital) | 5.2 | 5.3 | .805 |

| Transfer (facility) | 9.9 | 7.0 | <.001 |

| Routine | 29.7 | 25.0 | <.001 |

| Died (%) | 12.4 | 12.1 | .146 |

| Hospital region (%) | |||

| Midwest | 17.4 | 20.0 | .001 |

| South | 46.2 | 43.4 | .003 |

| West | 12.9 | 14.4 | .026 |

| Northeast | 23.5 | 22.3 | .131 |

| Patient LOS | 21.0 | 18.4 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; ED, emergency department; LOS, length of stay;

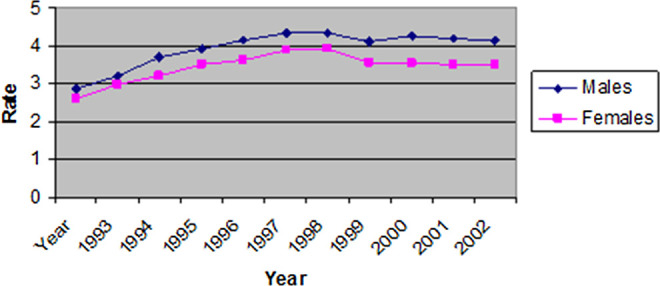

Rate of PEG tube placement increased by 38% over the study period (Figure 1). The rate of increase was 2.71 PEG placements per 1000 patients in 1993 to 3.75 PEG placements per 1000 hospitalized patients in 2003. The increase in PEG tube placement rates was more for males (44%) than for females (33%).

Figure 1.

Temporal trends in PEG tube placement in the hospitalized elderly individuals by gender from 1993 to 2003.

Table 2 shows the frequency of select primary diagnoses in those with PEG tube over the study period. The primary diagnosis associated with PEG tube placement were cerebrovascular disease in 13.7%, aspiration pneumonia in 12%, pneumonia in 3.11%, malnutrition was 1.94%, congestive heart failure in 1.78%, and dysphagia was 1.36%.

Table 2.

Primary Diagnosis Among All Patients Who Got PEG Tubes Over the Study Over a 10-Year Period

| Primary diagnosis | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrovascular disease | 37 533 | 13.66 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 33 021 | 12.02 |

| Pneumonia | 8539 | 3.11 |

| Malnutrition | 5334 | 1.94 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4877 | 1.78 |

| Dysphagia | 3725 | 1.36 |

Abbreviation: PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

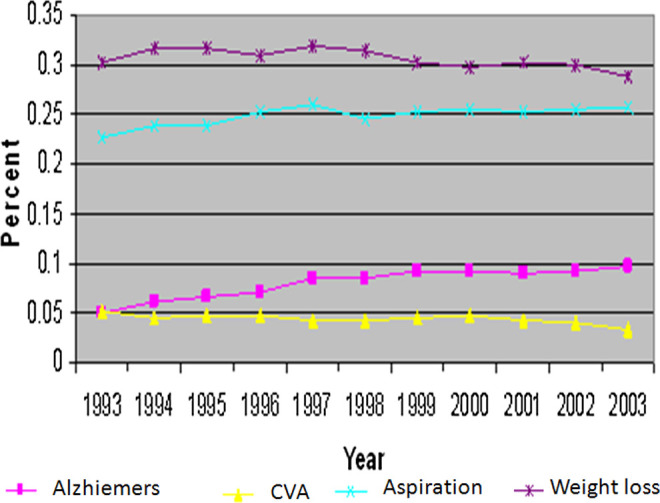

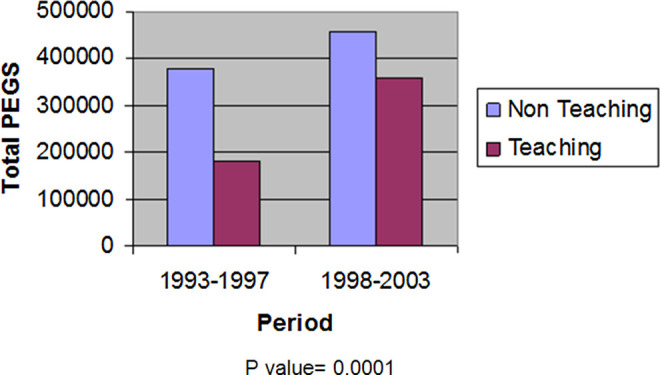

Patients with Alzheimer’s dementia who received a PEG tube doubled from 5% to 10% over the study period (Figure 2). In comparison, over the same period, PEG tube placement decreased in patients with cerebrovascular disease from 5% to 3%, and in patients with weight loss from 31% to 28%. In patients with aspiration, an increase in PEG tube placement from 22% to 26% was noted. During the study period, the adjusted length of stay decreased by approximately 7 days but the mortality remained essentially unchanged. Between the 2 time periods, there were significant increase in PEG tube placement in the teaching hospitals (P value .0001) but not among nonteaching hospitals (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Temporal trends in PEG tube placement in the hospitalized elderly individuals in selected by comorbid conditions from 1993 to 2003.

Figure 3.

Total PEG tube placement by era comparing teaching versus nonteaching hospitals.

Discussion

This study provides a unique perspective on national temporal trends in PEG tube placement within United States. We report that PEG tube placement continues to rise among elderly patient and placement rates have doubled among hospitalized elderly individuals with dementia over the 10-year study period. Despite increases in PEG tube placement study period, adjusted length of stay decreased (by ∼7 days) whereas mortality remained essentially unchanged.

Despite inconclusive evidence that enteral tube feeding provides any benefit in patients with dementia (in terms of survival time, mortality risk, quality of life, nutritional parameters, physical functioning, and improvement or reduced incidence of pressure ulcers), we show that PEG tube placement in patients with dementia continues to rise. 20 In a recent study, Teno and colleagues 10 reported that more than one-third of severely cognitively impaired residents in US nursing homes have feeding tubes. The decision to start enteral tube feeding is not evidence based and is influenced by complex ethical issues. 21 Common justifications given may include prolongation of life by correcting malnutrition, reducing risk of aspiration and pressure ulcers, pneumonia and other infections, and/or optimizing quality of life by promoting physical comfort.

Some studies suggest that enteral tube feeding may actually increase mortality, morbidity, and reduce quality of life. 22,23 Placement of PEG tube is an invasive surgical procedure with significant risk of postoperative adverse events including aspiration pneumonia, esophageal perforation, tube migration, bleeding, and wound infection. 22 Up to one-third of the older tube-fed patients experience transient gastrointestinal adverse effects (ie, vomiting, diarrhea). 24 Serious mechanical problems, such as bowel perforations, are rare (<1%). 25 However, tube dislodgement, blockage, and leakage are quite common (4-11%) and often necessitate transfer to an acute care facility. 24,26 It may also increase pulmonary secretions, cause increased agitation leading to the need for physical or chemical restraint to avoid self-extubation. Agitated demented patients may require physical or chemical restraints to prevent tube dislodgment, and tube feeding has been shown to be associated with greater restraint use. Thus, the best available evidence fails to demonstrate significant health benefits of tube feeding in advanced dementia. 27

There are several limitations of the current study. The database does not have patient identifiers, thereby limiting further detailed analysis of their individual hospital stays. This study is limited in being able to detail residents’ clinical characteristics, the nursing homes’ fiscal, organizational, and other demographic features that may provide more information on the rate of PEG tube placement. The study encompasses the period from 1993 to 2003 and does not look at more recent trends.

Conclusions

Over a 10-year period, the PEG tube use in hospitalized elderly patients increased significantly. More importantly, approximately 1 in 10 PEG tubes placed are in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Further consideration of these trends of PEG tube placement and the potential for its overuse in future patients with advanced dementia appears warranted.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to John A. Williams for manuscript assistance. Dr Tilford is supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000039-04).

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: supported in part by PHS (NIH AG028718), GRECC, and CAVHS. Dr Tilford is supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000039-04).

References

- 1. Roche V. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Clinical care of PEG tubes in older adults. Geriatrics 2003;58(11):22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer’s disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alzheimer’s Association. 2009. Alzheimer’s Disease: Facts and Figures. http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/report_alzfactsfigures2010.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2011.

- 4. National Vital Statistics National Center for Health Statistics. Reports. Deaths: Final Data for 2007. 2010;58(19). http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morrison RS, Siu AL. Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA. 2000;284(1):47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teno JM, Mor V, DeSilva D, Kabumoto G, Roy J, Wetle T. Use of feeding tubes in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2002;287(24):3211–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gessert CE, Mosier MC, Brown EF, Frey B. Tube feeding in nursing home residents with severe and irreversible cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1593–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, Kabumoto G, Mor V. Clinical and organizational factors associated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290 ( 1 ):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Gozalo PL, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2010;303(6):544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alvarez-Fernandez B, Garcia-Ordonez MA, Martinez-Manzanares C, Gomez-Huelgas R. Survival of a cohort of elderly patients with advanced dementia: nasogastric tube feeding as a risk factor for mortality. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, Baskin-Lyons S, Morrison RS. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(4):594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murphy LM, Lipman TO. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1351–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nair S, Hertan H, Pitchumoni CS. Hypoalbuminaemia is a poor predictor of survival after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in elderly patients with dementia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(1):133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS); 2005. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

- 16. Holman RC, Curns AT, Belay ED, Steiner CA, Schonberger LB. Kawasaki syndrome hospitalizations in the United States, 1997 and 2000. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 pt 1):495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2002 Nationwide Inpatient Sample Technical Documentation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18. O'Malley KJ, Cook KF, Price MD, Wildes KR, Hurdle JF, Ashton CM. Measuring diagnoses: ICD code accuracy. H ealth Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1620–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Westfall JM, McGloin J. Impact of double counting and transfer bias on estimated rates and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Med Care. 2001;39(5):459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sampson EL, Candy B, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;15(2):CD007209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Angus F, Burakoff R. The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube: medical and ethical issues in placement. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abuksis G, Mor M, Segal N, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: high mortality rates in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(1):128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peck A, Cohen CE, Mulvihill MN. Long-term enteral feeding of aged demented nursing home patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(11):1195–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schrag SP, Sharma R, Jaik NP, et al. Complications related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. A comprehensive clinical review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16(4):407–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Attansasio A, Bedin M, Stocco S, et al. Clinical outcomes and complications of enteral nutrition among older adults. Minerva Med. 2009;100(2):159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenberger LH, Newhook T, Schirmer B, Sawyer RG. Late accidental dislodgement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube: an underestimated burden on patients and the health care system. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(10):3307–3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sampson EL, Candy B, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;15(2):CD007209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer’s disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grant MD, Rudberg MA, Brody JA. Gastrostomy placement and mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 1998;279(24):1973–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rabeneck L, Wray NP, Petersen NJ. Long-term outcomes of patients receiving percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(5):287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]