Abstract

The human 8q24 gene desert contains multiple enhancers that form tissue-specific long-range chromatin loops with the MYC oncogene, but how chromatin looping at the MYC locus is regulated remains poorly understood. Here we demonstrate that a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), CCAT1-L, is transcribed specifically in human colorectal cancers from a locus 515 kb upstream of MYC. This lncRNA plays a role in MYC transcriptional regulation and promotes long-range chromatin looping. Importantly, the CCAT1-L locus is located within a strong super-enhancer and is spatially close to MYC. Knockdown of CCAT1-L reduced long-range interactions between the MYC promoter and its enhancers. In addition, CCAT1-L interacts with CTCF and modulates chromatin conformation at these loop regions. These results reveal an important role of a previously unannotated lncRNA in gene regulation at the MYC locus.

Keywords: CCAT1-L lncRNA, super-enhancer, chromatin looping, MYC, CTCF

Introduction

The increased sensitivity of experimental assays has revealed that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) impact a variety of important biological processes (reviewed in1,2). Aberrant expression of lncRNAs has been linked to cancers with distinct modes of action (reviewed in3). For example, HOTAIR is highly expressed in breast tumors and has been reported to promote cancer metastasis by targeting chromatin repressor Polycomb proteins to specific genomic loci4. LincRNA-p21 in association with hnRNP-K serves as a repressor in p53-dependent transcriptional responses5 or suppresses target mRNA translation in coordination with the RNA-binding protein HuR6. MALAT1 has been implicated in the regulation of cell growth and tumor metastasis7,8. These findings suggest that lncRNAs may serve as important regulators in tumorigenesis although the expression regulation of lncRNAs in specific human tumors and their mechanisms involved in tumorigenesis remain to be explored.

Enhancers are a class of DNA regulatory sequences that can activate gene expression independent of their proximity or orientation to their target genes9. Enhancers often form long-range chromatin loops with their target genes to control temporal- and tissue-specific gene expression during development and their mis-regulation contributes to human diseases10. A large portion of enhancers can be transcribed into enhancer RNAs (eRNAs)11, which have been proposed to contribute to gene activation12,13,14,15,16. In addition, super-enhancers were recently identified and shown to consist of large clusters of transcriptional enhancers formed by binding of master transcription factors/mediators and to be associated with genes that control and define cell identity17,18. Thus, it would be interesting to know whether super-enhancers are transcribed and whether they are regulated by RNA transcripts.

The expression of the human MYC oncogene is complex and is regulated at multiple levels, including enhancers, promoters, transcription factors and chromatin state17,19,20,21. The human 8q24 region includes a gene desert containing enhancers forming chromatin loops with the MYC promoter located several hundred kilobases telomerically. These chromatin interactions are tissue-specific in prostate, breast and colorectal cancers19. In colorectal cancer (CRC), one well-characterized loop is between a locus 335 kb upstream of MYC (MYC-335) and the MYC promoter. MYC-335, the site harboring an important CRC risk SNP (rs6983267), is a transcriptional enhancer that promotes the binding of transcription factor 4 (TCF4) specifically in CRC22,23. Importantly, mice lacking MYC-335 were resistant to intestinal tumors, although MYC transcripts were only modestly reduced24. Very recently, the region upstream of MYC has been reported to contain an exceptionally large super-enhancer17 and such a super-enhancer is tumor type specific in cancer cells, but not in its healthy counterparts20. However, how these chromatin loops at the 8q24 MYC locus are regulated remains unknown.

Human 8q24 has recently been reported to express several lncRNAs in different human tumors. PRNCR1 (8q24)25 binds to the androgen receptor (AR) and is involved in the AR-mediated gene activation in prostate cancers26. However, it is not expressed in CRC (Supplementary information, Figure S1). Instead, two other CRC-specific lncRNAs transcribed from 8q24 were recently reported. CCAT1 (Colorectal Cancer Associated Transcript 1) is 2 600 nt in length and is a highly specific marker for CRC27, and its upregulation is evident in both pre-malignant conditions and through all disease stages in CRC28. CCAT2, a 340 nt ncRNA transcribed from the MYC-335 region, appeared to enhance invasion and metastasis through MYC-regulated miRNAs miR-17-5p and miR-20a29. However, we have been unable to detect CCAT2 in any human CRC tissue samples or CRC-derived cell lines examined (Supplementary information, Figure S1).

Here we report that a novel 5 200 nt CRC-specific lncRNA, CCAT1-L (CCAT1, the Long isoform), is transcribed from a locus 515 kb upstream of MYC (MYC-515), a super-enhancer region of MYC17,20, and plays a role in MYC transcriptional regulation. We demonstrate that CCAT1-L localizes to its site of transcription and functions in the maintenance of chromatin looping between the MYC promoter and its enhancers in coordination with CTCF. Together, these results reveal a novel connection between the chromatin organization regulated by a lncRNA and MYC expression in a specific human cancer.

Results

CCAT1-L, a novel CRC-specific lncRNA, is abundantly transcribed from a locus 515 kb upstream of MYC on 8q24

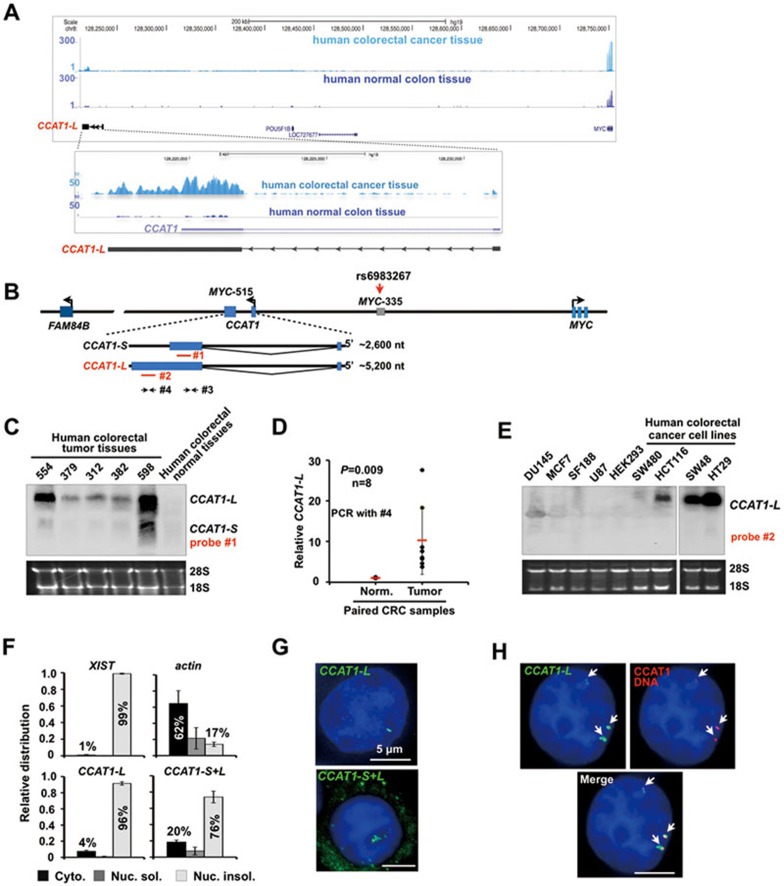

By sequencing paired CRC/control mucosa samples from a Chinese patient, we have identified a previously unreported lncRNA, CCAT1-L, that is abundantly and specifically expressed in CRC (Supplementary information, Table S1 and Figure S1). CCAT1-L is transcribed from 8q24.21 ― 515 kb upstream of the MYC locus (MYC-515) (Figure 1A). It is 5 200 nt in length, contains two exons and is polyadenylated as revealed by oligo (dT) selection followed by northern blot (Supplementary information, Figure S2A). 3′ RACE further confirmed its 3′ end and the splicing between the two exons (Supplementary information, Figure S1A and data not shown). Interestingly, CCAT1, a 2 600 nt lncRNA identified using Representational Difference Analysis (RDA) and cDNA cloning27, was shown to be highly associated with pre-malignant as well as all disease stages in colon cancer tumorigenesis27,28. Importantly, CCAT1-L that we identified here overlaps with CCAT1 (Figure 1A and 1B), suggesting a positive correlation of CCAT1-L expression with colon cancer. For clarity, we refer the 2 600 nt CCAT1 as CCAT1-S throughout this study.

Figure 1.

CCAT1-L, a nuclear-retained lncRNA, is specifically expressed in human CRC tissue samples. (A) RNA-seq of paired CRC/control mucosa samples from a Chinese patient revealed that a novel lncRNA, CCAT1-L, is transcribed from a locus 515 kb upstream of the MYC locus (MYC-515) on 8q24. Note that we refer the previously annotated 2 600 nt CCAT1 as CCAT1-S throughout this study27. (B) A schematic view of CCAT1 locus and its adjacent genomic information on 8q24. The locus 335 kb upstream of the MYC locus (MYC-335) contains an enhancer and a CRC risk SNP22,23. Red lines denote antisense (AS) probes recognizing either both CCAT1 isoforms (#1) or only CCAT1-L (#2) in northern blot; arrows denote PCR primer sets that recognize either both CCAT1 isoforms (#3) or only CCAT1-L (#4). (C) Northern blot validated CCAT1-L expression in human CRC patient samples. (D) The relative expression of CCAT1-L in CRC tissues and paired control mucosa samples from the same patients. The primer sets only recognizing CCAT1-L was used (#4 in B). P values from one-tailed t-test in the pairwise comparison are shown. (E) Northern blot confirmed CCAT1-L expression in human CRC cell lines. (F) CCAT1-L is associated with the nuclear insoluble fractions. Total RNAs from HT29 cells were separated into cytoplasmic, nuclear soluble, and nuclear insoluble fractions. Bar plots represent relative abundance of RNAs in the nuclear soluble and insoluble fractions as measured by RT-qPCR. #3 or #4 described in B were used to detect either both CCAT1 isofroms or CCAT1-L only. Error bars represent standard deviation (± SD) in triplicate experiments. (G) CCAT1-L is exclusively nuclear retained, while CCAT1-S is cytoplasmically distributed. RNA ISH (green) was performed with Dig-labeled probes (B) either recognizing CCAT1-L (top panel) or both isoforms of CCAT1 (bottom panel) in HT29 cells. (H) CCAT1-L accumulates at its site of transcription. Double FISH of CCAT1-L (green) and its adjacent DNA region (red). A single Z stack of representative images acquired with an Olympus IX70 DeltaVision Deconvolution System microscope is shown. DAPI is in blue and the white scale bar in all images denotes 5 μm. Representative images are shown (G, H). In C and E, 18S and 28S rRNAs were used as loading controls. Supportive data are included in Supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2.

We further confirmed extensive transcription of CCAT1-L in CRC tissue samples from several other patients by northern blots and CCAT1-L-specific RT-qPCR (Figure 1C and 1D). Consistent with the expression pattern of CCAT1-S27, the expression of CCAT1-L is undetectable or very low in paired mucosa samples (Figure 1C and 1D) and other normal human tissue samples (Supplementary information, Figure S2B). The same northern blot probe also recognizes CCAT1-S, but CCAT1-S is expressed at a much lower level compared to CCAT1-L in human CRC patient tissue samples examined (Figure 1C). In addition, we observed that CCAT1-L is specifically expressed in cultured CRC-derived cell lines, such as HCT116, HT29 and SW48 (Figure 1E). Finally, sequence conservation analysis revealed that CCAT1-L is human specific and no ortholog was seen in other species examined (data not shown).

The human 8q24 gene desert region has recently been shown to express distinct lncRNAs in different human tumors25,27,29 (Supplementary information, Figure S1B). However, these lncRNAs were undetectable in the sequencing data of paired CRC/control mucosa samples (Supplementary information, Table S1 and Figure S1C), or could not be detected in the CRC-derived cell lines that we examined (Supplementary information, Figure S1D). Thus, the significance and functional implications of these RNAs in CRC remain unclear.

CCAT1-L is a nuclear-retained lncRNA

As the two CCAT1 isoforms overlap, we decided to characterize them in greater detail. First, both RNAs are polyadenylated (Supplementary information, Figure S2A), with halflife of about 6-8 h in HT29 cells (data not shown). Second, knockdown of CCAT1-L by an optimized phosphorothioate-modified antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (ASO) led to the simultaneous disruption of CCAT1-S (Supplementary information, Figure S2C), suggesting that the short isoform may be derived from CCAT1-L. Further analysis revealed alternative polyadenylation (APA) sites in CCAT1-L at a genomic position close to the 3′ end of CCAT1-S (data not shown). Third, we observed that CCAT1-S and CCAT1-L are localized to different subcellular compartments. By nuclear/cytoplasmic RNA fractionation, we found that CCAT1-L shows an association with chromatin as tight as Xist, a lncRNA that regulates chromatin compaction during X-chromosome inactivation30 (Figure 1F). Fractions with both CCAT1 isoforms revealed a less tight association of these RNAs with chromatin (Figure 1F), suggesting that CCAT1-S is cytoplasmic. This was further confirmed by RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) with probes that either detect CCAT1-L only or both CCAT1 isoforms. CCAT1-L is exclusively located in the nucleus and accumulates in striking nuclear foci in CRC cell lines examined (Figure 1G, top panel, and data not shown). In contrast, when a probe recognizing both isoforms of CCAT1 was used in the ISH, we found that fluorescent signals appeared in both cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 1G, bottom panel), suggesting that CCAT1-S is located in the cytoplasm. This is in agreement with the previous report that CCAT1-S is a cytoplasm-located lncRNA31. Finally, we found that the nuclear-retained CCAT1-L does not colocalize with marker proteins of known nuclear bodies, including Cajal bodies, paraspeckles, nuclear speckles and PML bodies (data not shown). However, double DNA/RNA FISH (Figure 1H) clearly revealed that CCAT1-L accumulates at or near its site of transcription, suggesting a possible role of CCAT1-L in local gene expression or chromatin organization.

Knockdown of CCAT1-L reduces MYC expression

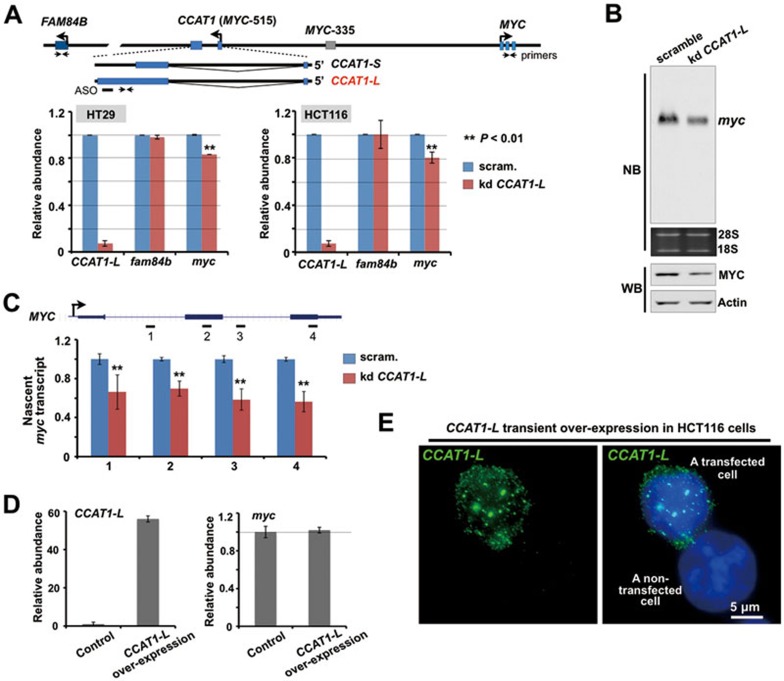

The in cis accumulation of CCAT1-L suggests a possible role in local gene expression. As only a few genes are expressed from the 8q24 region (Figure 1A and Supplementary information, Figure S1B), we examined the relative expression of their steady-state mRNAs after knockdown of CCAT1-L. While knockdown of CCAT1-L by ASO had no effect on the expression of FAM84B, which is located 667 kb centromeric to CCAT1-L, it led to modestly reduced expression of MYC, which is located 515 kb telomeric to CCAT1-L, as revealed by both RT-PCR and northern blot in HT29 cells (Figure 2A and 2B). In addition, we noticed a reduction of MYC protein after CCAT1-L ASO treatment (Figure 2B). This reduction was also observed at different times after the ASO treatment (data not shown) and in another CRC cell line HCT116 (Figure 2A). Importantly, we found that knockdown of CCAT1-L greatly reduced the transcription of nascent MYC RNA (Figure 2C), further suggesting that CCAT1-L regulates MYC expression at the transcriptional level. Nevertheless, while the reduction on the steady-state MYC mRNA that we observed was modest, it is possible that this at least partly reflects the known complexity of MYC regulation21.

Figure 2.

CCAT1-L regulates MYC expression in cis. (A) Knockdown of CCAT1-L led to modestly reduced expression of MYC in both HT29 and HCT116 cells. Top, bars represent ASO and arrows represent primer sets. Bottom, bar plots represent relative expression of CCAT1-L, MYC and FAM84B 36 h post the ASO treatment (normalized to actin). (B) Northern blot and western blot (WB) revealed the reduced expression of MYC after knockdown of CCAT1-L in HT29 cells. Actin was used as a loading control in WB. (C) CCAT1-L regulates MYC expression at the transcriptional level. A crude preparation of nuclei was subjected to nuclear run-on assay under the indicated conditions in HT29 cells. Nascent transcription of MYC detected from scramble ASO-treated nuclei was defined as one. (D) Overexpression of CCAT1-L in trans in expression vector resulted in no apparent activation of MYC. Left, RT-qPCR validated the increased expression of CCAT1-L in the pEGFP-C1 vector in HCT116 cells. Right, the overexpression of CCAT1-L in HCT116 cells did not lead to increase of MYC expression, as revealed by RT-qPCR. (E) Overexpression of CCAT1-L in vectors resulted in aberrant localization in the nucleus. RNA ISH (green) was performed with a probe recognizing CCAT1-L (Figure 1B) in HCT116 cells transfected with the CCAT1-L-expressing vector. Note that the overexpressed CCAT1-L produced from transfection vectors assembled as numerous nuclear dots. Representative images are shown. Scale bar, 5 μm. Error bars in A, C and D represent ± SD in triplicate experiments. In A and C, P values from one-tailed t-test in the pairwise comparison are shown.

We next expressed CCAT1-L from a plasmid expression vector to see whether it could raise MYC expression. However, we observed that transient overexpression of CCAT1-L in trans resulted in no apparent activation of MYC (Figure 2D) and that the overexpressed CCAT1-L from the expression vector localizes to numerous nuclear sites (Figure 2E) rather than to its endogenous in cis site of accumulation (Figure 1H). This lack of effect was not surprising, given that regulation of CCAT1-L on MYC may require an in-cis action. Also, we have previously reported that other nuclear-retained lncRNAs, when expressed from transfected vectors, did not localize to the sites of their genomic counterpart regions32,33 or exert their roles in cis33.

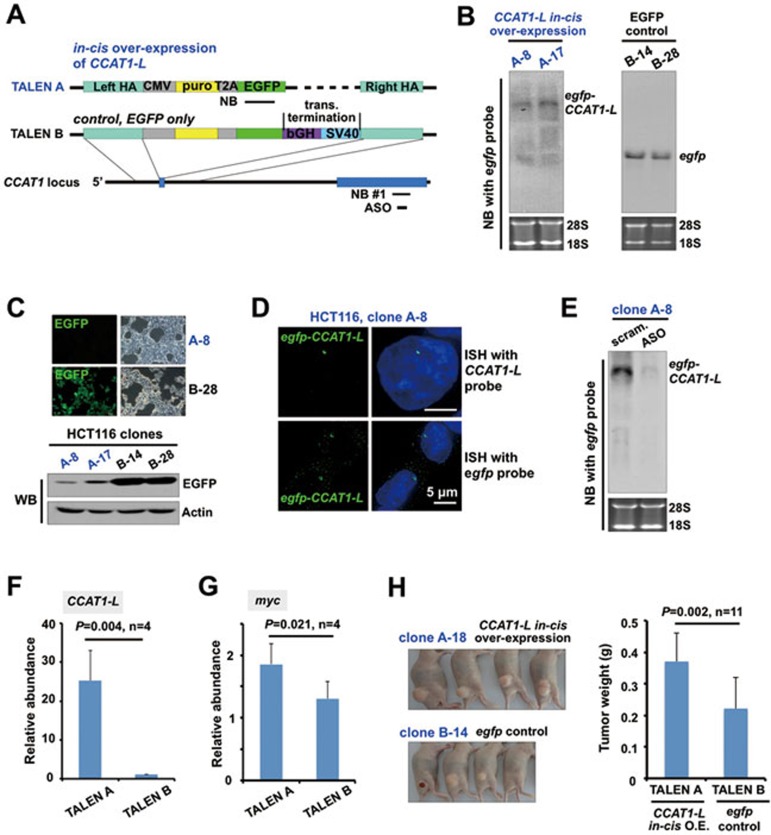

In cis overexpression of CCAT1-L enhances MYC expression and promotes tumorigenesis

Recently developed targeted genome-editing technologies using engineered nucleases, such as transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), provide a precise way to manipulate chromatin regions of interest (reviewed in34). We therefore applied TALENs to achieve in cis overexpression of CCAT1-L in HCT116 cells, which normally express a low level of CCAT1-L (Figure 1E). We inserted a CMV promoter and egfp just upstream of the CCAT1 genomic locus to achieve a single allele insertion to express the fusion egfp-CCAT1-L RNA in cis (Figure 3A and Supplementary information, Figure S3A and S3B, TALEN A). As it has been shown that the insertion of a double poly(A) site cassette into the genome by zinc finger nucleases (ZNF) led to an efficient transcriptional stop35, we inserted such a double poly(A) site cassette downstream of egfp to terminate the transcription of CCAT1-L at the same genomic locus to obtain the control cell line (Figure 3A, Supplementary information, Figure S3A and S3C, TALEN B). Thus, these two TALEN-engineered cell lines offered a convenient system to allow transcription of either egfp-CCAT1-L (TALEN A) or egfp (TALEN B) from the same promoter in cis. However, using similar approaches we have been unable to obtain complete knockdown of CCAT1-L, owing to amplification and hence multiple alleles of this locus in CRC lines.

Figure 3.

In cis overexpression of CCAT1-L enhances MYC expression and tumorigenesis. (A) A schematic view of the strategy to in cis express CCAT1-L in HCT116 cells by TALEN. TALEN A, the CCAT1-L in cis overexpression cell line. A cassette of CMV promoter and sequences of puromycin and egfp mRNAs was inserted just upstream of the first exon of CCAT1 by TALEN. TALEN B, the control cell line that overexpresses egfp. The same cassette of TALEN A but with two additional poly(A) sites to terminate the transcription downstream of egfp was inserted into the same genomic location as that in TALEN A (see Supplementary information, Figure S3 for details). Note that the transcription occurred in both egfp-CCAT1-L- and egfp-overexpressing cell lines. (B) Northern blot validated the overexpression of egfp-CCAT1-L (left panel) or egfp (right panel) in different TALEN lines by using a probe recognizing egfp shown in A. (C) In cis overexpressed egfp-CCAT1-L (B) was poorly translated into EGFP due to its nuclear retention, while the overexpressed egfp was efficiently translated into EGFP. Fluorescence microscopy (top) and WB (bottom) of representative TALEN A or TALEN B lines are shown. (D) Nuclear-retained egfp-CCAT1-L exclusively accumulated as a single nuclear dot, as revealed by ISH probes recognizing either CCAT1-L or egfp in the representative TALEN A clone. (E) Northern blot validated that egfp-CCAT1-L can be efficiently knocked down by the ASO that targets CCAT1-L, assayed with a probe recognizing egfp. (F) RT-qPCR revealed the overexpression of CCAT1-L in TALEN A lines, but not in control TALEN B lines (normalized to actin and the non-engineered HCT116 cells). Four lines of TALEN A and TALEN B cells were analyzed individually. (G) In cis overexpression of egfp-CCAT1-L enhanced MYC expression, as revealed by RT-qPCR (normalized to actin and the non-engineered HCT116 cells). The same lines of TALEN A and TALEN B cells in F were analyzed. (H) In cis overexpression of egfp-CCAT1-L increased tumor formation in a mouse xenograft model. Xenograft tumors were collected 4 weeks after inoculation of cells. Left, representative xenograft tumors generated from a TALEN A and a TALEN B line are shown. Right, comparison was made between the egfp-CCAT1-L in cis overexpressing TALEN A lines and the egfp in cis overexpressed TALEN B lines. Note that xenograft tumors raised from individual in cis egfp-CCAT1-L-overexpressing HCT116 cell lines were larger than those raised from control TALEN-engineered cell lines. Error bars in F-H represent ± SD in indicated multiple experiments. P values from one-tailed t-test in the pairwise comparison are shown. 18S and 28S rRNAs were used as loading controls in all northern blots. Supportive data are included in Supplementary information, Figures S1-S4.

As expected, with a northern blot probe that recognizes egfp, we found that egfp-CCAT1-L or egfp was expressed in the indicated TALEN lines (Figure 3B). Importantly, we observed that egfp-CCAT1-L was rarely exported to the cytoplasm for EGFP translation (Figure 3C, 3D and Supplementary information, Figure S3D), further confirming that it is a nuclear-retained lncRNA. In contrast, all control TALEN lines that only express egfp resulted in a strong EGFP fluorescence (Figure 3C and Supplementary information, Figure S3D). In addition, the expression of egfp-CCAT1-L was further confirmed by a northern blot probe that recognizes CCAT1 (Supplementary information, Figure S3E), while no overexpressed CCAT1-L was detected in the egfp-expressing control TALEN lines (Supplementary information, Figure S3F), suggesting that the transcriptional terminator after egfp is efficient. The egfp-CCAT1-L TALEN lines achieved a 15-30-fold increase in in cis expression of CCAT1-L, while CCAT1-L expression remained low in egfp-overexpressing control TALEN lines (Figure 3F and Supplementary information, Figure S3E and S3F). Finally, we found that the overexpressed egfp-CCAT1-L was not efficiently processed to CCAT1-S, as only the long isoform of CCAT1 appeared in all northern blots (Figure 3B, 3E and Supplementary information, Figure S3E). Although these results suggest that the biogenesis of two isoforms of CCAT1 requires further attention, they also reveal that the in cis overexpression offers a clear system to evaluate the function of CCAT1-L in the current study.

Importantly, egfp-CCAT1-L can also be knocked down by the same ASO that targets CCAT1-L, as revealed by northern blot with an egfp probe (Figure 3E). Furthermore, this ASO treatment also led to a consistent reduction of MYC transcripts in several in cis CCAT1-L-overexpressing HCT116 cell lines (Supplementary information, Figure S4A). It is worth noting that the in cis activated egfp-CCAT1-L RNA does not colocalize to known nuclear bodies (Supplementary information, Figure S4B), but instead locates as one single nuclear accumulation (Figure 3D) to its site of transcription (Figure 4E). These characteristics of egfp-CCAT1-L resemble known molecular features of the endogenous CCAT1-L (Figure 1F-1H).

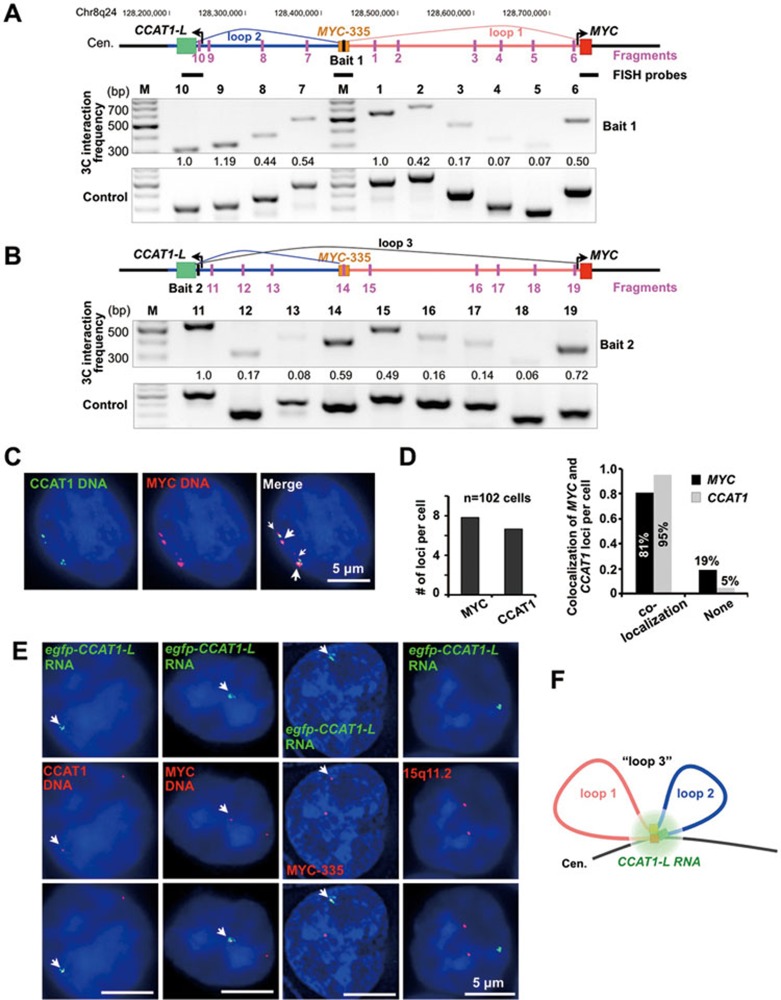

Figure 4.

The long-range interaction between the MYC promoter and its upstream regulatory elements. (A) The existence of multiple chromatin loops in the upstream region of MYC in HT29 cells. Physical map of the region spanning a 550 kb distance with CCAT1-L (MYC-515) at one end and MYC at the other, interrogated by 3C. Top, the position of the constant fragment containing MYC-335, a known region that is looping with the MYC promoter22, is marked by a black bar (bait 1); positions of HindIII restriction target fragments are marked by pink bars and primers were designed accordingly. Bottom, 3C interaction frequencies of the constant fragment with other fragments revealed the increased interaction between MYC-335 and MYC promoter and between MYC-335 and MYC-515. 3C products were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (examples were shown in Supplementary information, Figure S5B). The relative abundance of each 3C PCR product was determined using ImageJ, normalized by each corresponding input signal and the bait PCR product (set as 1.0), and labeled underneath. (B) The chromatin loops in the upstream region of MYC. Top, the position of the constant fragment containing CCAT1-L locus (MYC-515) is marked by a black bar (bait 2); see A for details. (C) Double DNA FISH of CCAT1-L (green) and MYC (red) genomic loci in HT29 cells. FISH probes are labeled as black bars in A. White arrows indicate the co-localized loci from a representative cell. (D) The majority of CCAT1-L and MYC genomic regions are spatially close. Left, each HT29 cell contains multiple CCAT1-L and MYC loci, and the number of each locus per cell was calculated from totally 102 cells counted. Right, the majority of CCAT1-L loci in HT29 cells co-localize with MYC loci. (E) CCAT1-L RNA accumulates to chromatin regions at or near the MYC locus. Double FISH of egfp-CCAT1-L (green) with CCAT1-L DNA region, MYC locus and MYC-335 region revealed the co-localization of egfp-CCAT1-L with these loci, but not with 15q11-13. Position-specific 10-15 kb probes (shown in A) or a probe recognizing15q11-1332 were used in DNA FISH. White arrows indicate the single-allele overexpressing egfp-CCAT1-L or its co-localized DNA regions in representative cells. (F) A schematic drawing of chromatin loops at the MYC locus. Loop 1 (pink line) is between the MYC promoter (red box) and MYC-335 (brown box); loop 2 (blue line) is between MYC-335 and MYC-515 (green box); the spatially close localization of loop 1 and loop 2 resulted in the chromatin looping between the MYC promoter and MYC-515, which is “loop 3”. In C and E, a single Z stack of representative images acquired with an Olympus IX70 DeltaVision Deconvolution System microscope is shown. Supportive data are included in Supplementary information, Figure S5.

Compared to the control engineered TALEN B HCT116 cells (Figure 3A), the in cis overexpressed egfp-CCAT1-L enhanced MYC expression (Figure 3G). Furthermore, we also observed that egfp-CCAT1-L-overexpressing HCT116 cells grew faster than the control cell lines under low serum culture conditions (data not shown). Moreover, transplantation of egfp-CCAT1-L-overexpressing HCT116 cell lines resulted in larger xenograft tumors in nude mice when compared to egfp-overexpressing control cell lines (Figure 3H). Taken together, we conclude that CCAT1-L plays a role in tumorigenesis by positively regulating MYC expression in cis.

The genomic locus encoding CCAT1-L is spatially close to the MYC locus

How does CCAT1-L regulate MYC transcription across a distance of 515 kb on 8q24? It is known that chromatin looping can juxtapose genes or enhancers to spatially distant regions36. For example, a well-characterized chromatin loop between a locus 335 kb upstream (MYC-335) and the MYC promoter in CRC was reported, and MYC-335 was proposed to act as a transcriptional enhancer for MYC22,23. We reasoned that the CCAT1-L-transcribing locus MYC-515 may also locate close to MYC by forming a chromatin loop. By using Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) to measure the chromatin interaction frequency of a constant fragment at MYC-335 with a number of target fragments between the MYC promoter and MYC-515, we found that the highest interaction frequencies were between MYC-335 and the MYC promoter, and between MYC-335 and MYC-515 (Figure 4A). The results were confirmed when a constant fragment was set at MYC-515 (Figure 4B) or in the MYC promoter (Supplementary information, Figure S5A) in 3C experiments. These results clearly suggest that the genomic locus encoding CCAT1-L (MYC-515) is spatially close to MYC and MYC-335 in addition to the known chromatin loop between the MYC promoter and MYC-335 (Figure 4B).

To further confirm our 3C results, we visualized the localization of the MYC promoter and MYC-515 by double DNA FISH in single HT29 cells. We designed two short probes (∼10 kb in length) that recognize either the MYC promoter or MYC-515 to achieve a higher resolution for double DNA FISH. The 8q24 region is amplified to at least 6 copies in HT29 cells37,38. We found that on average each probe can detect 6 copies of the CCAT1 locus and 8 copies of the MYC locus in HT29 cells (Figure 4C and 4D). Importantly, 95% of the detected CCAT1 loci colocalize with MYC loci (Figure 4D).

Although CRC-derived cancer cell lines usually contain multiple chromatin copies of 8q24 (Figure 4C and 4D), the in cis activated egfp-CCAT1-L HCT116 cell line provided a clearer system that allowed us to visualize the localization of CCAT1-L with its adjacent chromatin. In agreement with the spatially close localization of MYC-515, MYC-315 and the MYC locus, we found that these three loci, although separated by 515 kb in distance on 8q24, are associated with CCAT1-L RNA as revealed by the fact that in cis activated egfp-CCAT1-L exhibited the strong colocalization with all of these loci (Figure 4E, and a schematic view is shown in Figure 4F). Meanwhile, a control DNA FISH that recognizes 15q11-13 region32 showed no co-localization with the in cis activated egfp-CCAT1-L. Taken together, the chromatin organization at the MYC locus and the unique localization pattern of CCAT1-L strongly support the notion that CCAT1-L can regulate MYC expression in cis.

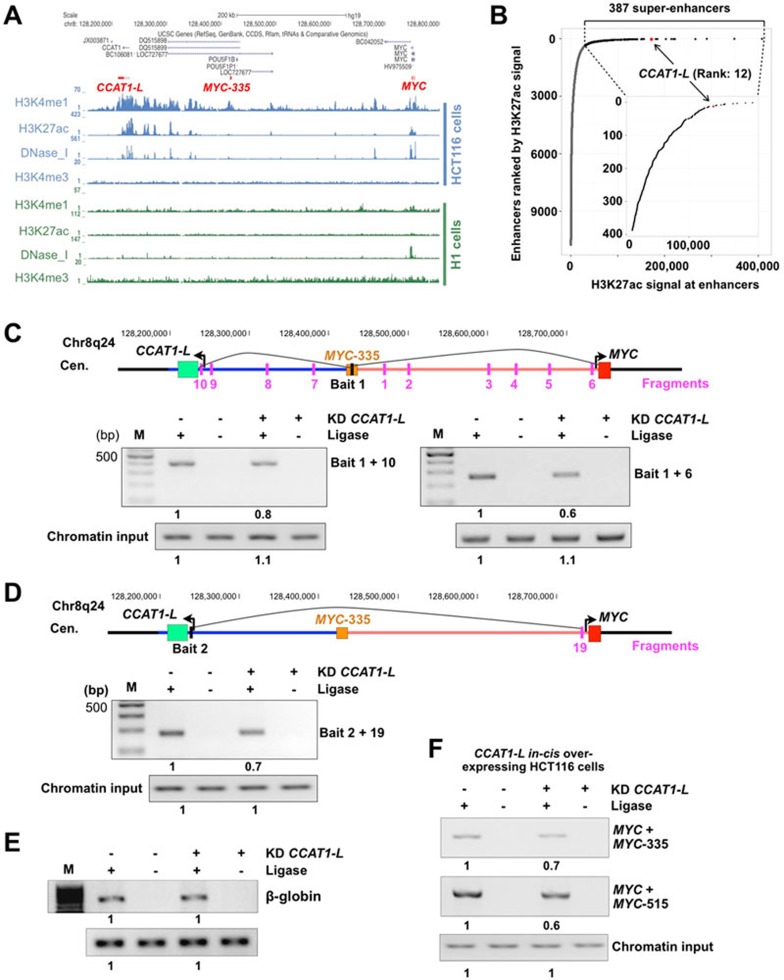

The genomic locus encoding CCAT1-L is a strong super-enhancer

One way to activate gene expression across large distances is by enhancer DNA elements that form long-range chromatin loops with their target genes9. Recent genome-wide analyses of chromatin markers in different human cell lines39 have provided a rich resource to allow us to analyze the chromatin modifications in the MYC-515 region. Genome-wide mapping of enhancers in HCT116 cells by searching for locations with high H3K27 acetylation (H3K27ac), high H3K4 mono-methylation (H3K4me1) but low H3K4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3)40 revealed that the genomic locus encoding CCAT1-L is an enhancer that spans up to 150 kb in length (Figure 5A). The size of this enhancer is distinct from that of a typical enhancer which is ∼1.5 kb in length on average17. Analyzing the distribution of H3K27ac signal across enhancers further revealed that this region is a strong super-enhancer in HCT116 cells20 (Figure 5B). Also consistent with a role as a super-enhancer, this region is enriched for CBP/P300 binding sites and hypersensitive to DNase I but is devoid of H3K27me3 modification (Figure 5A and data not shown). Moreover, in agreement with the highly cell- or tissue-specific feature of enhancers9, we found that this enhancer is associated with enhancer-specific histone modifications in CRC cell lines, but not in other cell lines, such as the human embryonic stem cell H1 line (Figure 5A). This is consistent with the very recent report that the gene desert surrounding MYC contains tumor type-specific super-enhancers in cancer cells, but not in their healthy counterparts20.

Figure 5.

CCAT1-L is required to maintain the chromatin looping at the MYC locus. (A) The chromatin region between MYC-515 and MYC-335 exhibits strong characteristics of a super-enhancer in HCT116 cells but not in H1 cells (histone modifications data were retrieved from ENCODE collection39). CCAT1-L, MYC-335 and MYC loci are highlighted in red. (B) Distribution of H3K27ac signal across enhancers (outer figure) and super-enhancers (inner figure) in HCT116 cells. Rank and H3K27ac signal of enhancers and super-enhancers were downloaded from the literature20. 387 super-enhancers (black points) were identified from uneven distribution of H3K27ac signal among normal enhancers (grey points), and the CCAT1-L-associated super-enhancer (red point) is ranked as #12 super-enhancers with high H3K27ac signals. (C, D) Knockdown of CCAT1-L reduced the chromatin looping at the MYC locus. The long-range interaction frequencies between three chromatin regions (MYC-335/MYC, MYC-335/MYC-515, and MYC/MYC-515) were reduced after knockdown of CCAT1-L as revealed by 3C assays in HT29 cells. Over 90% of CCAT1-L was depleted after the ASO treatment in 3C assays (data not shown). (E) Knockdown of CCAT1-L has no effect on the chromatin looping at the β-globin locus. The same HindIII restriction fragments were designed for 3C primers and PCRs were performed at the same time as C and D. (F) Knockdown of CCAT1-L reduced the chromatin looping at the MYC locus in HCT116 cell line with CCAT1-L in cis overexpression. The long-range interaction frequencies between the chromatin regions examined in B and C were also reduced after knockdown of CCAT1-L in the HCT116 cell line as revealed by 3C assays. In C-F, the relative abundance of each 3C PCR product was determined using ImageJ and labeled underneath. 3C experiments were repeated three times. Supportive data are included in Supplementary information, Figures S5 and S6.

CCAT1-L is required for the maintenance of chromatin looping at the MYC locus

Recent studies have suggested that a large fraction of enhancers can be bidirectionally transcribed into eRNAs11 which have been proposed to contribute to gene activation at a distance12,13,14,15,16, presumably by the establishment or maintenance of enhancer-promoter looping. We asked whether the CRC-specific super-enhancer region-transcribed CCAT1-L plays a role in the maintenance of chromatin looping between the MYC promoter and its enhancers.

We measured the relative chromatin interaction frequency at the known interaction regions on 8q24 (Figure 4) by 3C experiments before and after knockdown of CCAT1-L. Strikingly, we observed that the interaction frequencies between MYC-335 and the MYC promoter and between MYC-335 and MYC-515 were significantly reduced after CCAT1-L knockdown (Figure 5C). The interaction frequency between MYC-515 and the MYC promoter was also greatly reduced under the same treatment (Figure 5D). In contrast, another known loop at the β-globin locus was not altered (Figure 5E). Moreover, knockdown of CCAT1-L in the CCAT1-L-in cis overexpressing cell line also reduced the interaction frequencies between the looping regions upstream of MYC (Figure 5F). Importantly, these observations were further supported by 3C-Seq41 with bait fragment recognizing the CCAT1-L locus (MYC-515) in control and CCAT1-L-depleted cells (Supplementary information, Figure S6). Many long-range chromatin interactions were detected within the 500-kb region between the CCAT1-L and MYC loci (Supplementary information, Figure S6), which was consistent with available 5C datasets generated by the University of Washington ENCODE GROUP (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTrackUi?db=hg19&g=wgEncodeUw5C). Importantly, loops between MYC and MYC-335, and between MYC-335 and MYC-515 were most significantly affected by knockdown of CCAT1-L (Supplementary information, Figure S6). Together, these results suggest that the super-enhancer region-transcribed CCAT1-L is required for the maintenance of certain chromatin loops at the MYC locus in CRC cancer cells. We observed the same phenomenon when the same chromatin loops between the MYC promoter and its enhancers were assayed using different sets of “bait” and “fragment” PCR primer sets (data not shown) and in two additional biological repeats (data not shown). In all assays, 3C PCR products were Sanger sequenced to confirm that they mapped to the designed separated chromatin regions with a HindIII cutting site (Supplementary information, Figure S5B).

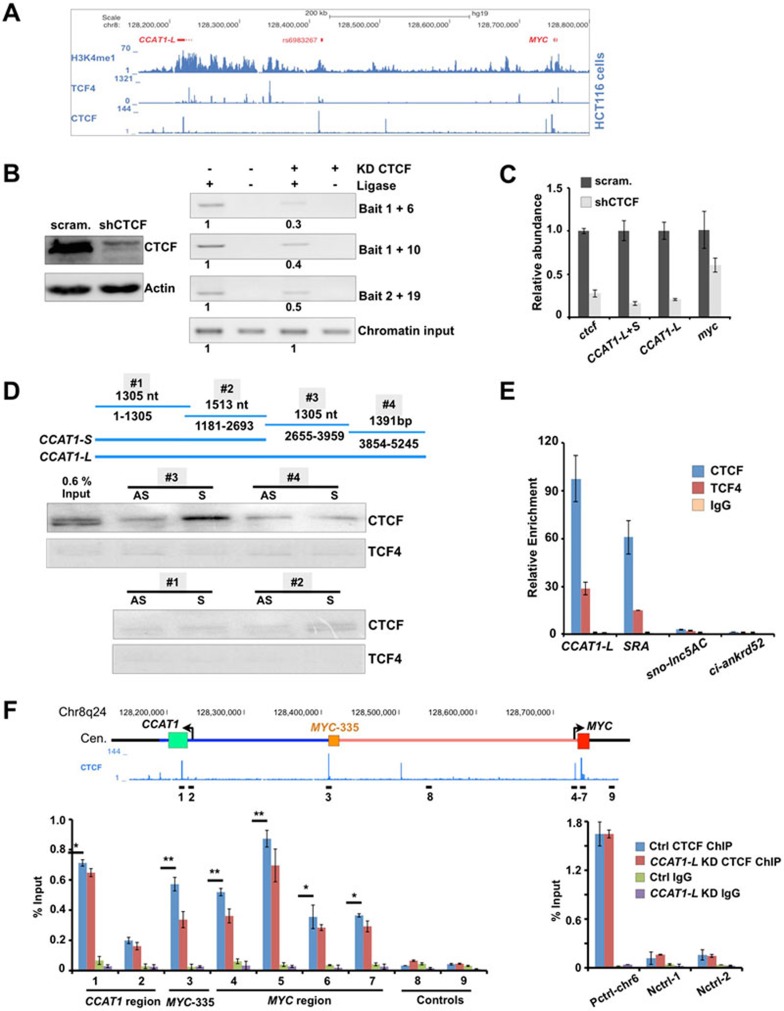

CTCF plays a role in mediating long-range chromatin interactions between the MYC promoter and its enhancers

Analyses of the available ChIP-seq datasets39 revealed that TCF4 and CTCF are highly enriched in this 8q24 region in HCT116 cells (Figure 6A). Extensive TCF4 binding in the chromatin region between MYC-515 and MYC-335 was consistent with the notion that this chromatin region is a super-enhancer that can recruit transcriptional factors (Figure 5A). Expression of a dominant-negative TCF4 in HT29 cells resulted in reduced expression of both MYC and CCAT1-L (Supplementary information, Figure S7A), confirming a role of TCF4 in both MYC42 and CCAT1-L regulation, and suggesting that the transcription of CCAT1-L is responsive to TCF4 signaling in CRC.

Figure 6.

CCAT1-L interacts with CTCF and modulates CTCF binding to chromatin. (A) ChIP-seq revealed that TCF4 and CTCF are enriched at 8q24 in HCT116 cells (ChIP-seq data were retrieved from ENCODE collection39). (B) CTCF is required for chromatin looping at 8q24. Left, knockdown of CTCF was achieved using shRNA against CTCF as confirmed by WB. Right, the long-range interaction frequencies between three chromatin regions (MYC-335/MYC, MYC-335/MYC-515, and MYC/MYC-515, primers used in Figure 4) were reduced after knockdown of CTCF as revealed by 3C assays in HT29 cells. The relative abundance of each 3C PCR product was determined using ImageJ and labeled underneath. 3C experiments were repeated for three times. (C) CTCF is required for MYC and CCAT1-L expression. The relative abundance of MYC and CCAT1-L was analyzed by RT-qPCR in control and CTCF-knockdown HT29 cells. (D) CCAT1-L and CTCF interact in vitro. Top, a schematic view of four overlapping CCAT1-L RNA fragments for IVT. Bottom, biotin-labeled RNA pull-down assay using different fragments of CCAT1-L transcript in HT29 nuclear extracts showed that one fragment of CCAT1-L binding to CTCF. No CCAT1-L fragment was specifically associated with TCF4. (E) Interaction between endogenous CCAT1-L and CTCF was confirmed by RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP). RIP was performed with HT29 cells after UV crosslinking by using anti-CTCF, anti-TCF4 and anti-IgG, followed by RT-qPCR. Bar plots represent fold enrichments of RNAs immunoprecipitated by each indicated antibody over anti-IgG. SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator54; sno-lnc5AC, H/ACA sno-lncRNA32; ci-ankrd52, a circular intronic RNA33. (F) CCAT1-L modulates CTCF binding to chromatin. Knockdown of CCAT1-L reduced the interaction of CTCF to its occupied sites in chromatin. ChIP with anti-CTCF in scramble- and CCAT1-L ASO-treated HT29 cells. Data were expressed as the percentage of CTCF co-precipitating DNAs in MYC promoter, MYC-335, MYC-515 regions and negative CTCF binding sites on 8q24, versus input under each indicated condition (left). Control CTCF ChIPs were performed on positive and other negative CTCF binding sites (right). P values from one-tailed t-test in the pairwise comparison are shown (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). In E and F, error bars represent ± SD in triplicate experiments. Supportive data are included in Supplementary information, Figure S6.

In addition, the specific enrichment of CTCF at sites for chromatin looping formation in the MYC promoter, MYC-335 and MYC-515 regions (Figure 6A) suggests that these chromatin loops observed at the MYC locus are CTCF-mediated. It is in agreement with a critical role of CTCF in mediating chromatin looping (rather than only functioning as an “insulator”)43,44,45. This is what we have observed for the 8q24 region. Knockdown of CTCF disrupted these chromatin loops, as revealed by reduced chromatin interaction frequencies between the MYC promoter and its enhancers (Figure 6B). Importantly, knockdown of CTCF led to reduced expression of MYC and CCAT1-L (Figure 6C and Supplementary information, Figure S7B), supporting the notion that CTCF and CTCF-mediated chromatin looping are required to maintain proper transcription of both MYC and CCAT1-L. This also indicates the possibility that CTCF and CCAT1-L may participate in a positive regulatory network in control of MYC transcription by regulating the higher chromatin organization of 8q24 surrounding the MYC locus.

CCAT1-L interacts with CTCF and modulates CTCF binding to chromatin at the MYC locus

As CCAT1-L is required for the maintenance of chromatin looping at the MYC locus (Figure 5 and Supplementary information, Figure S6), we set up analyses to understand the underlying mechanisms by searching for CCAT1-L-interacting proteins using biotin-labeled RNA pull-down assays. TCF4 and CTCF are enriched at MYC-515 (Figure 6A) and it is known that many DNA-binding proteins can also bind to RNAs46,47. As a first step to examine CCAT1-L-associated proteins, we asked whether CCAT1-L is associated with TCF4 and CTCF.

CCAT1-L is 5 200 nt in length, which is too long to achieve an efficient biotin-labeled in vitro transcription (IVT) with a proper folding in denatured buffer (data not shown). Therefore, we generated several sense and antisense biotin-labeled IVT fragments that span the full sequence of CCAT1-L, each overlapping another by 100 nt at both ends (Figure 6D). After incubation with nuclear extracts isolated from HT29 cells with individual biotin-labeled RNA fragments, we found that only the sense biotin-labeled 2 655-3 959 fragment of CCAT1-L, which does not overlap with CCAT1-S, specifically interacted with CTCF (Figure 6D). In contrast, no fragment could specifically bring down TCF4 or another abundant nuclear protein p54nrb (Figure 6D and data not shown), confirming the specificity of this pull-down assay. Furthermore, we confirmed the specific interaction between CCAT1-L and CTCF by RNA immunoprecipitation (Figure 6E). We found that CCAT1-L was efficiently co-precipitated with antisera directed against CTCF, but much less efficiently with those targeting TCF4 (Figure 6E). Other abundant ncRNAs, H/ACA sno-lncRNA32 or ciRNA33 , could not be pulled down by these antibodies, demonstrating the specificity of the RNA precipitation assays. Together, these analyses strongly indicate that CCAT1-L specifically interacts with CTCF.

We finally asked whether the interaction of CCAT1-L and CTCF contributes to the observed role of CCAT1-L in the maintenance of the long-range chromatin interactions between the MYC promoter and its enhancers (Figures 4, 5 and Supplementary information, Figure S6). Knockdown of CCAT1-L led to a modest reduction of CTCF binding to chromatin at their occupied chromatin sites in loop-forming regions at the MYC locus (Figure 6F). This suggests that CCAT1-L lncRNA may act to locally concentrate CTCF or allosterically modify CTCF binding to chromatin to maintain the chromatin looping in the 8q24 region surrounding the MYC locus in CRC cancers. We have consistently observed only modest effects on CTCF binding to chromatin after knockdown of CCTA1-L, which is in agreement with the recent report that CTCF-occupied chromatin sites often anchor constitutive chromatin interactions44.

Discussion

Recent studies reported that many enhancers can bidirectionally express non-polyadenylated noncoding RNAs (eRNAs) with very low copy numbers11,48,49. Such eRNAs have been proposed to play an enhancer-like role in transcriptional activation at a distance, presumably by the establishment or maintenance of enhancer-promoter looping12,13,14,15,16. In addition, AR-associated lncRNAs PRNCR1 and PCGEM1 were shown to be involved in the regulation of AR-dependent gene activation events by a sequential recruitment of PRNCR1 and PCGEM1 to AR and the recognition of H3K4me3 marks by PCGEM1-recruited PYGO2 to enhance interactions of AR-bound enhancers with target gene promoters genome-widely26. In the current study, we found that the locus 515 kb upstream of MYC is a super-enhancer (Figure 5A and 5B), which is about 150 kb in length and forms chromatin loops with MYC (Figures 4, 5, Supplementary information, Figures S5 and S6). Interestingly, it has been very recently highlighted as a tumor type-specific super-enhancer20. Our results showed that this MYC locus-related super-enhancer (Figure 5A) expresses a human colorectal cancer-specific lncRNA CCAT1-L (Figure 1). This lncRNA is polyadenylated and is specifically accumulates in cis in the nucleus (Figure 1). It positively regulates MYC transcription (Figures 2 and 3) by promoting chromatin interactions between MYC and its upstream regulatory elements (Figures 4, 5 and Supplementary information, Figure S6). Different from the reported eRNAs or PCGEM1 that are associated with components of Mediators, cohesin or chromatin modification enzymes12,13,14, or directly open the chromatin accessibility15, our data suggest that CCAT1-L interacts with CTCF and modulates CTCF binding to chromatin to maintain the looping at the MYC locus (Figure 6).

CTCF has been proposed to act as one of the master candidates as a global genome organizer to coordinate chromatin structures and regulate gene expression50. Recent analyses of CTCF-associated higher-order chromatin structures by ChIA-PET43 and the long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters by 5C44,45 have revealed a primary role of CTCF in mediating chromatin looping, rather than only functioning as an insulator51. CTCF is particularly involved in the formation of the intermediate-length chromatin loops at scales of 100 kb-1 Mb in a more constitutive way44. Consistent with this notion, we showed here that CTCF plays an important role in MYC expression and in mediating 300-550 kb long-range chromatin interactions between enhancers and the MYC promoter (Figure 6A-6C). However, importantly, we also observed that the association of CTCF with its occupied chromatin sites was influenced by additional context in cancers, such as the presence of the lncRNA CCAT1-L in CRC (Figure 6). CTCF has been shown to bind to RNAs52,53,54. Depletion of RNAs either affected its binding to cohesin54 or altered CTCF binding to chromatin52. We found that knockdown of CCAT1-L led to the modest reduction of CTCF binding to chromatin (Figure 6F). This observation not only further confirmed that the CTCF-occupied sites at the MYC locus are constitutive, but also was consistent with the notion that these chromatin loops at the MYC locus are under regulation19,20. However, we do not yet know how precisely CTCF coordinates with CCAT1-L to regulate the chromatin looping at the MYC locus. Also, it is possible that CCAT1-L may interact with other chromatin organizers or modifiers in addition to CTCF.

MYC regulation is extremely complex. The physiologic transcriptional control of this gene still is not fully understood due to the lack of a complete annotation of regulatory elements across different tissue types21. Our study presented here, as well as others19,20, has demonstrated that the megabase-sized region of gene desert around MYC contains many regulatory elements (enhancers and super-enhancers) that form looping interactions with MYC in a tissue-/tumor type-specific manner. Thus, the proper chromatin organization of 8q24 gene desert region can be the key to precisely regulate MYC transcription under different physiologic conditions. In agreement with this notion, MYC transcripts in mice lacking MYC-335 were modestly reduced24. Knockdown of CTCF led to the reduced interactions between the MYC promoter and its enhancers (Figure 6B) and a decreased MYC transcription as well (Figure 6C). In addition, knockdown of CCAT1-L RNA reduced the enhancer-promoter interactions at the MYC locus (Figures 5 and Supplementary information, Figure S6) and MYC transcription (Figure 2A-2C). The in cis overexpression of this lncRNA promoted MYC transcription and enhanced tumorigenesis (Figure 3 and Supplementary information, Figure S4), presumably by modulating enhancer-promoter interactions (Figure 5 and Supplementary information, Figure S6). Thus, we propose that the expression of CCAT1-L RNA may influence the chromatin organization of 8q24 at the MYC locus, contributing in part to the aberrant expression of MYC in human colorectal cancer pathogenesis. However, as it has been reported that transcriptional recruitment at certain locus may affect the expression of adjacent genes55, we do not exclude the possibility that the acquirement of the transcription activity in the CCAT1-L locus during CRC pathogenesis may also contribute to the regulation of MYC transcription.

Although we do not know to what extent CCAT1-L-regulated looping cross-talks with other aspects of MYC regulation, this study represents yet another component of the complicated MYC region. Finally, as this region also expresses distinct lncRNAs in other types of human cancers, it will be of interest to learn whether other 8q24 lncRNAs behave in a similar way in MYC transcription in different cancers.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and ASO treatment

Human cell lines were cultured using standard protocols provided by ATCC. Phosphorothioate-modified oligodeoxynucleotide (ASO) were synthesized at BioSune, Shanghai, China. The ASO was introduced into HT29 or HCT116 cells by nucleofection (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The scramble- and ASO-treated cells were collected for the following experiments.

Total RNA isolation, human tissue RNA samples, RT-PCR, RT-qPCR and northern blot

Total RNAs from cultured cells with different treatments were extracted with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen). Twenty human tissue RNA samples were purchased from Ambion. For RT-PCR, after treatment with DNase I (Ambion, DNA-free TM kit), the cDNA was transcribed with SuperScript II (Invitrogen), followed by PCR. For qPCR, the relative expression of genes was quantified to actin mRNA from three independent experiments. Primers for PCR and qPCR are listed in Supplementary information, Table S2. For northern blot, equal amounts of total RNAs collected from cultured cells and primary tissue samples from patients were resolved on 1.5% agarose gels and northern blot was carried out as described previously33. Digoxigenin-labeled antisense CCAT1-L probe and egfp probe were made using either SP6 or T7 RNA polymerases by IVT with the DIG Northern Starter Kit (Roche). Primers for northern blot probes are listed in Supplementary information, Table S2.

Patient samples and RNA extractions from tissues and deep sequencing for gene expression analysis

Human paired CRC/control mucosa samples were obtained from Changzheng Hospital, Shanghai under the strict guidance of ethical committee. After frozen tissue samples were powdered in liquid nitrogen, Trizol was added to extract RNA. RNA quality was examined by gel electrophoresis and only paired RNA with high quality was used for following analyses, including RNA-seq. RNA-seq libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and then applied to sequencing on Illumina HiSeq 2000 in CAS-MPG Partner Institute for Computational Biology Omics Core, Shanghai and Genergy, Shanghai. In all, 52 and 59 million 1 × 100 single reads of the paired CRC/control mucosa RNA samples were obtained and were uniquely mapped to the hg19 genome with over 85% of mapping rates for both cases. The gene expression analysis was carried out as described previously32 and genes (mRNAs and lncRNAs) altered significantly in both samples are listed in Supplementary information, Table S1.

Nuclear/cytoplasmic RNA fractionation, nuclear soluble/insoluble RNA fractionation and polyadenylated/non-polyadenylated RNA separation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA isolation in HT29 cells, nuclear soluble and insoluble RNA fractionation were performed as described before32. Polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA separation in HT29 cells was carried out as described previously in HeLa cells56. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was then used to evaluate the relative abundance of both CCAT1s, XIST and actin in each sample.

RNA ISH and immunofluorescence microscopy

To detect CCAT1-L and CCAT1-S, RNA ISH was carried out as previously described with in vitro transcribed digoxigenin-labeled antisense probes32. For colocalization studies, cells were co-stained with rabbit anti-Nucleolin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-p54nrb (BD) and mouse anti-Coilin (Sigma). The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were taken with a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope or with an Olympus IX70 DeltaVision RT Deconvolution System microscope.

RNA/DNA double FISH

Sequential RNA/DNA double FISH experiments were carried out as described previously32. After RNA ISH, cells were denatured at 80 °C for 5 min in prewarmed 2× SSC and 70% deionized formamide, pH 7.0. Next, cells were hybridized with denatured labeled DNA probe prepared by Nick Translation (Empire Genomics) overnight. After hybridization, two washes of 10 min at 37 °C with 2× SSC/50% deionized formamide, pH 7.0, followed by two washes of 15 min at 37 °C with 1× SSC and two washes of 15 min at 37 °C with 2× SSC were performed. Slides were then mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI. Analyses were performed on single Z stacks acquired with an Olympus IX70 DeltaVision RT Deconvolution System microscope. Colocalization signals were detected in > 95% double-positive cells.

Double DNA FISH and statistical analyses

Double DNA FISH experiments were carried out as described above with minor modifications. Position-specific 10-15 kb probes were amplified by long-range PCR directly from genomic DNAs with primers listed in Supplementary information, Table S2. These DNA FISH probes that target the specific looping interactions of 8q24 were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (green) or 594 (red) by Nick Translation (Empire Genomics). After fixation and permeabilization, cells were denatured at 80 °C for 5 min in prewarmed 2× SSC and 70% deionized formamide pH 7.0. Next, cells were hybridized overnight at 37 °C with denatured labeled DNA probes. After hybridization, two washes of 10 min at 37 °C with 2× SSC/50% deionized formamide, pH 7.0, followed by two washes of 15 min at 37 °C with 1× SSC and two washes of 15 min at 37 °C with 2× SSC were performed. Slides were then mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI. Pictures were taken with an Olympus IX70 DeltaVision RT Deconvolution System microscope. Colocalization signals were analyzed in double-positive cells.

UV crosslinking RNA immunoprecipitation

UV crosslinking RIP was carried out as described before33. Two 10 cm2 dishes of HT29 cells with 90%-100% confluence were washed twice with 5 ml cold PBS and irradiated at 300 mJ/cm2 at 254 nm in a Stratalinker. Cells were collected and resuspended in 1 ml RIP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mM VRC, protease inhibitor cocktail). Then cells were homogenized by 3 rounds of sonication on ice. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was pre-cleared with Dynabeads G (Invitrogen) with 20 μg/ml yeast tRNA at 4 °C for 30 min. The pre-cleared lysate was incubated with Dynabeads G that were pre-coated with 2 μg antibodies of anti-CTCF (Millipore), anti-TCF4 (Millipore) or IgG (Sigma) for 4 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed sequentially with washing buffer I (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM VRC) and washing buffer II (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM VRC, 1 M urea) for multiple times. The immunoprecipitated complex was eluted from Dynabeads G by adding 140 μl elution buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 1% SDS). 5 μl of 10 mg/ml proteinase K was then added to the retrieved RNA samples and incubated at 55 °C for 30 min, followed by RNA extraction and qPCR.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

1 × 107 cultured cells with each treatment were washed with ice-cold PBS, crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde and quenched by 0.125 M glycine. After being resuspended with 1 ml ChIP lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA), cells were sonicated to achieve the majority of DNA fragments with 200-500 bp. Supernatants were collected and pre-cleared with Dynabeads G in ChIP lysis buffer with the supplement of 100 μg BSA and 100 μg ssDNA. Then, the pre-cleared cell lysates were used for ChIP with 2 μg CTCF antibody (Millipore) for overnight incubation at 4 °C. The beads were then washed with 600 μl ChIP lysis buffer, 600 μl high salt wash buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA), 600 μl of LiCl immune complex wash buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 0.5% Igepal, 0.5% deoxycholate, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA), followed by two washes with 600 μl 1× TE Buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitated complex was eluted from Dynabeads G by adding 200 μl fresh-prepared elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3) with rotation at room temperature (RT) for 15 min. Then the reverse crosslinking was carried out by adding 8 μl of 5 M NaCl and incubating at 65 °C for 4 h, followed by incubating with the supplement of 4 μl of 0.5 M EDTA and 10 μl proteinase K (10 mg/ml) at 55 °C for 2 h. DNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, followed by qPCR with the primers listed in Supplementary information, Table S2.

Biotin-labeled RNA pull-down assay

Biotin-labeled RNAs pull-down assay was performed as described33,57,58 with minor modifications. Biotin-labeled CCAT1-L truncation probes were in vitro transcribed with the Biotin RNA Labeling Mix (Roche) and AmpliScripe T7/SP6-flash Transcription Kit (Epicentre). 4 μg biotinylated RNA was denatured for 5 min at 65 °C in PA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl) and slowly cooled down to RT. 2 × 107 HT29 cell pellet was used for each assay. Briefly, HT29 cell nuclei33 were resuspended in 1 ml RIP buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mM VRC, protease inhibitor cocktail). The nuclei were sonicated on ice followed by centrifugation at 13 000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and pre-cleared by applying 40 μl Streptavidin Dynabeads for 20 min at 4 °C. Then 20 μg/ml yeast tRNA was added to block nonspecific binding and incubated for 20 min at 4 °C. Folded RNAs were then added and incubated for 1.5 h at RT, followed by the addition of 40 μl Streptavidin Dynabeads to incubate for 1.5 h. Beads were washed with RIP buffer containing 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and denatured in 1× SDS loading buffer. The retrieved proteins were analyzed by western blot with anti-CTCF (Millipore) and anti-TCF4 (Millipore) antibodies.

Nuclear run-on (NRO)

The NRO assay in HT29 cells was performed as described previously33 with minor modifications. In brief, HT29 cells were washed with cold PBS quickly and collected for NRO assay 24 h post nucleofection with ASOs. Collected cells were incubated in swelling buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl2, 3 mM CaCl2) on ice for 5 min and were then collected by centrifugation. Cell pellets were subjected to lysis twice with 1.5 ml lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 2mM MgCl2, 3 mM CaCl2, 0.5% Igepal, 10% glycerol, and 2 U/ml RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor) to obtain purer nuclei. The resulting nuclear pellets were resuspended in 100 μl NRO buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl, 0.1% sarkosyl, 2 U/ml RNase inhibitor and 10 mM DTT) containing 0.1 mM ATP, GTP, CTP and BrUTP (Sigma). Transcription was performed for 3 min on ice and then 5 min at RT. The reaction was stopped by addition of 600 μl Trizol to extract RNA, followed by the DNase I (Ambion, DNA-free TM kit) treatment to remove genomic DNA. Purified RNAs were incubated with 2 μg anti-BrdU antibody (Sigma) or equal amount of IgG antibody (Sigma) at 4 °C for 2 h and were then immunoprecipitated with Dynabeads G pre-coated with yeast tRNA (Sigma). Precipitated RNAs were extracted by Trizol and were used for cDNA synthesis and qPCR analysis.

Chromosome conformation capture (3C)

3C was performed as described59 with modifications. HT29 cells and HT29 cells under different treatments were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at RT, followed by quenching the crosslinking with addition of 0.125 M glycine. The nuclei were collected and dounced in lysis buffer, followed by adding 400 U of HindIII restriction enzyme for overnight digestion at 37 °C with shaking. Ligation was performed for 4 h at 16 °C followed by 1 h incubation with 50 U of T4 DNA ligase at RT. Reverse crosslinking was performed in the presence of proteinase K overnight at 65 °C. The genomic DNA was then extracted by phenol-chloroform. After RNase A treatment, the genomic DNA was qualified with an input primer to balance the input chromatin across different samples. After normalization with input, equal amount of chromatin DNA was used in each PCR reaction to identify the chromatin loops and to compare the alterations between the targeted chromatin loops under different treatments. All 3C primers were designed according to a previous report60 and listed in Supplementary information, Table S2. The PCR products with expected sizes were Sanger sequenced to ensure that a specific product is exactly the sequence of the ligation event. The 3C control chromatin loop (β-globin) was also examined in the same way as described above.

3C Sequencing

The 3C-Seq libraries were prepared step by step as described by Stadhouders R et al.41. HindIII and DpnII were used as the primary and secondary restriction endonuclease. The 3C-Seq library was sequenced (70 bp reads) with Illumina HiSeq 2000. The 3C sequencing signals were normalized with both the total sequencing reads and the highest frequency signal nearby the bait primer. The relative signals were shown in a “CCAT1-to-MYC” viewpoint in Supplementary information, Figure S6.

In cis overexpression of CCAT1-L or EGFP with TALEN

All TALENs were designed and assembled according to literature61. The TALEN assembly kit was obtained from Addgene. The target sequence of CCAT1-L TALEN is TCATCATTACCAGCTGCCGT and TTTCTGTGAATCGTGAGCGT. The homologous arm sequences for donor plasmids are chr8: 128231306-128232194 and chr8: 128230503–128231297. After insertion of the homologous arms amplified from the genomic DNA of HCT116 cells into pCRII vector (backbone for Donor plasmid construction), the different regulatory modules (CMV/Puro/egfp and the BGH/SV40 poly(A) sites) were amplified from commercially available expression vectors including pEGFP-C1 and pLKO.1, followed by the insertion into the donor plasmid by overlapping PCRs to obtain desired TALEN vectors (Figure 3C and Supplementary information, Figure S4A). All plasmids were validated by Sanger sequencing. After transfection of individual sets of TALEN vectors and donor plasmids into HCT116 cells, puromycin was added to facilitate positive single clone screening. Genomic DNAs of selected single clones were extracted for the genotyping validation with appropriate sets of primers listed in Supplementary information, Table S2. The positive clones were scaled up for banking and detailed experiments (Figures 3, Supplementary information, Figures S4 and S5).

Tumor xenograft assay

Female nude mice between 4 and 6 weeks were obtained from SLAC laboratory animal company and bred in SPF animal house. All animal work was done in accordance with a protocol approved by the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center (Chinese Academy of Sciences). After 1 week feeding after reaching the animal house, mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 3-4 × 106 indicated cells of individual TALEN-engineered cell lines. Mice were maintained in SPF animal house and were sacrificed for tumor weight analyses when the xenografts reached about 1.5 cm in diameter (at 4 weeks).

Accession numbers

Raw sequencing dataset and bigWig track file of paired human CRC/control mucosa samples and 3C-Seq datasets are available for download from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession numbers GSE55259 and GSE55261.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs G Wei and R Stadhouders for assistance in 3C and 3C-seq experiments; Dr GG Carmichael for critical reading of the manuscript; Drs L Li, H Yao, YA Zeng and G Wang for materials; YJ Jiang, H Wu, S Zhu for technical support; and all other lab members for helpful discussion. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2014CB964800 and 2014CB910600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31271376 and 31322018), and the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (2012OHTP08 and 2012SSTP01).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Genome organization of 8q24 region lncRNAs (related to Figure 1).

Characterization of CCAT1-L (related to Figure 1).

Generation of CCAT1-L in-cis over-expressed cell lines and the control cell lines (related to Figure 3).

Characterization of CCAT1-L in-cis over-expression cell lines and the control cell lines (related to Figure 3).

Characterization of the long-range chromatin interaction between the MYC promoter and its upstream regulatory elements (related to Figures 4 and 5).

CCAT1-L regulates the long-range genomic interactions within the MYC-CCAT1 locus (related to Figures 4–5).

TCF4 and CTCF regulates MYC transcription in CRC-derived cell lines (related to Figure 6).

List of genes with altered expression pattern samples (related to Figure 1).

List of primers used in this study.

References

- Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulitsky I, Bartel DP. lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell. 2013;154:26–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Diederichs S. The hallmarks of cancer: a long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol. 2012;9:703–719. doi: 10.4161/rna.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010;142:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, et al. LincRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Mol Cell. 2012;47:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Eissmann M, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1180–1189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi V, Shen Z, Chakraborty A, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 controls cell cycle progression by regulating the expression of oncogenic transcription factor B-MYB. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulger M, Groudine M. Functional and mechanistic diversity of distal transcription enhancers. Cell. 2011;144:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orom UA, Shiekhattar R. Long noncoding RNAs usher in a new era in the biology of enhancers. Cell. 2013;154:1190–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, et al. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature. 2010;465:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature09033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai F, Orom UA, Cesaroni M, et al. Activating RNAs associate with Mediator to enhance chromatin architecture and transcription. Nature. 2013;494:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature11884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam MT, Cho H, Lesch HP, et al. Rev-Erbs repress macrophage gene expression by inhibiting enhancer-directed transcription. Nature. 2013;498:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nature12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Notani D, Ma Q, et al. Functional roles of enhancer RNAs for oestrogen-dependent transcriptional activation. Nature. 2013;498:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nature12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi K, Zare H, Dell'orso S, et al. eRNAs promote transcription by establishing chromatin accessibility at defined genomic loci. Mol Cell. 2013;51:606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orom UA, Derrien T, Beringer M, et al. Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell. 2010;143:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loven J, Hoke HA, Lin CY, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell. 2013;153:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte WA, Orlando DA, Hnisz D, et al. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadiyeh N, Pomerantz MM, Grisanzio C, et al. 8q24 prostate, breast, and colon cancer risk loci show tissue-specific long-range interaction with MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9742–9746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910668107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, et al. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell. 2013;155:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levens D. How the c-myc promoter works and why it sometimes does not. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2008;39:41–43. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz MM, Ahmadiyeh N, Jia L, et al. The 8q24 cancer risk variant rs6983267 shows long-range interaction with MYC in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:882–884. doi: 10.1038/ng.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuupanen S, Turunen M, Lehtonen R, et al. The common colorectal cancer predisposition SNP rs6983267 at chromosome 8q24 confers potential to enhanced Wnt signaling. Nat Genet. 2009;41:885–890. doi: 10.1038/ng.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur IK, Hallikas O, Vaharautio A, et al. Mice lacking a Myc enhancer that includes human SNP rs6983267 are resistant to intestinal tumors. Science. 2012;338:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.1228606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Nakagawa H, Uemura M, et al. Association of a novel long non-coding RNA in 8q24 with prostate cancer susceptibility. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Lin C, Jin C, et al. lncRNA-dependent mechanisms of androgen-receptor-regulated gene activation programs. Nature. 2013;500:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissan A, Stojadinovic A, Mitrani-Rosenbaum S, et al. Colon cancer associated transcript-1: a novel RNA expressed in malignant and pre-malignant human tissues. Int J Cancer J. 2012;130:1598–1606. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaiyan B, Ilyayev N, Stojadinovic A, et al. Differential expression of colon cancer associated transcript1 (CCAT1) along the colonic adenoma-carcinoma sequence. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H, Spizzo R, Atlasi Y, et al. CCAT2, a novel noncoding RNA mapping to 8q24, underlies metastatic progression and chromosomal instability in colon cancer. Genome Res. 2013;23:1446–1461. doi: 10.1101/gr.152942.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augui S, Nora EP, Heard E. Regulation of X-chromosome inactivation by the X-inactivation centre. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:429–442. doi: 10.1038/nrg2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam Y, Rubinstein A, Naik S, et al. Detection of a long non-coding RNA (CCAT1) in living cells and human adenocarcinoma of colon tissues using FIT-PNA molecular beacons Cancer Letters 2013 Feb 14. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yin QF, Yang L, Zhang Y, et al. Long noncoding RNAs with snoRNA ends. Mol Cell. 2012;48:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang XO, Chen T, et al. Circular intronic long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 2013;51:792–806. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Baas M, Diederichs S. Noncoding RNA gene silencing through genomic integration of RNA destabilizing elements using zinc finger nucleases. Genome Res. 2011;21:1944–1954. doi: 10.1101/gr.122358.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maston GA, Evans SK, Green MR. Transcriptional regulatory elements in the human genome. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 2006;7:29–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corzo C, Petzold M, Mayol X, et al. RxFISH karyotype and MYC amplification in the HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cell line. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:425–426. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Viars C, Arden K, et al. Comprehensive karyotyping of the HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cell line. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34:1–8. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium EP, Bernstein BE, Birney E, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CT, Corces VG. Enhancer function: new insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:283–293. doi: 10.1038/nrg2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadhouders R, Kolovos P, Brouwer R, et al. Multiplexed chromosome conformation capture sequencing for rapid genome-scale high-resolution detection of long-range chromatin interactions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:509–524. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, et al. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handoko L, Xu H, Li G, et al. CTCF-mediated functional chromatin interactome in pluripotent cells. Nat Genet. 2011;43:630–638. doi: 10.1038/ng.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Cremins JE, Sauria ME, Sanyal A, et al. Architectural protein subclasses shape 3D organization of genomes during lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;153:1281–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A, Lajoie BR, Jain G, Dekker J. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature. 2012;489:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdach J, O'Connell MR, Mackay JP, Crossley M. Two-timing zinc finger transcription factors liaising with RNA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiday LA, Maher LJ. Having it both ways: transcription factors that bind DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4118–4126. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santa F, Barozzi I, Mietton F, et al. A large fraction of extragenic RNA pol II transcription sites overlap enhancers. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hah N, Murakami S, Nagari A, Danko CG, Kraus WL. Enhancer transcripts mark active estrogen receptor binding sites. Genome Res. 2013;23:1210–1223. doi: 10.1101/gr.152306.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, Corces VG. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell. 2009;137:1194–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold M, Bartkuhn M, Renkawitz R. CTCF: insights into insulator function during development. Development. 2012;139:1045–1057. doi: 10.1242/dev.065268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Del Rosario BC, Szanto A, et al. Jpx RNA activates Xist by evicting CTCF. Cell. 2013;153:1537–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft RJ, Hawkins PG, Mattick JS, Morris KV. The relationship between transcription initiation RNAs and CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) localization. Epigenet Chromatin. 2011;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Brick K, Evrard Y, et al. Mediation of CTCF transcriptional insulation by DEAD-box RNA-binding protein p68 and steroid receptor RNA activator SRA. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2543–2555. doi: 10.1101/gad.1967810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Arun G, Mao YS, et al. The lncRNA Malat1 is dispensable for mouse development but its transcription plays a cis-regulatory role in the adult. Cell Rep. 2012;2:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Duff MO, Graveley BR, Carmichael GG, Chen LL. Genomewide characterization of non-polyadenylated RNAs. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R16. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff CA, Scheuermann JC, Surface LE, et al. Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;152:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagege H, Klous P, Braem C, et al. Quantitative analysis of chromosome conformation capture assays (3C-qPCR) Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1722–1733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostie J, Dekker J. Mapping networks of physical interactions between genomic elements using 5C technology. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:988–1002. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucl Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Genome organization of 8q24 region lncRNAs (related to Figure 1).

Characterization of CCAT1-L (related to Figure 1).

Generation of CCAT1-L in-cis over-expressed cell lines and the control cell lines (related to Figure 3).

Characterization of CCAT1-L in-cis over-expression cell lines and the control cell lines (related to Figure 3).