Abstract

To provide insight and to identify the occurrence of mechanistic changes in relation to variance in solvent-type, the solvent effects on the rates of solvolysis of three substrates, 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate, 2,2,2-trichloroethyl chloroformate, and 1-chloroethyl chloroformate, are analyzed using linear free energy relationships (LFERs) such as the extended Grunwald-Winstein equation, and a similarity-based LFER model approach that is based on the solvolysis of phenyl chloroformate. At 25.0 °C, in four common solvents, the α-chloroethyl chloroformate was found to react considerably faster than the two β,β,β-trichloro-substituted analogs. This immense rate enhancement can be directly related to the proximity of the electron-withdrawing α-chlorine atom to the carbonyl carbon reaction center. In the thirteen solvents studied, 1-chloroethyl chloroformate was found to strictly follow a carbonyl addition process, with the addition-step being rate-determining. For the two β,β,β-trichloro-substrates, in aqueous mixtures that are very rich in a fluoroalcohol component, there is compelling evidence for the occurrence of side-by-side addition-elimination and ionization mechanisms, with the ionization pathway being predominant. The presence of the two methyl groups on the α-carbon of 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate has additive steric and stereoelectronic implications, causing its rate of reaction to be significantly slower than that of 2,2,2-trichloroethyl chloroformate.

Keywords: Solvolysis; Addition-Elimination; Grunwald-Winstein Equation; Ionization; 2,2,2-Trichloroethyl Chloroformate; 2,2,2-Trichloro-1,1-Dimethylethyl Chloroformate; 1-Chloroethyl Chloroformate; Phenyl Chloroformate; Linear Free Energy Relationships (LFERs)

1. INTRODUCTION

Chloroformates are synthetically useful carboxylic acid esters whose chemistry [1–3] acquiesces them to have wide ranging applications as solvents, or industrial precursors, in myriad agricultural and pharmaceutical manufacturing processes [4–7]. Moreover the presence of syn geometry [8,9] in their structure, induces efficient chemoselective methods for cleaving and/or removing protecting groups [6,10–12]. For alkyl chloroformates, the aqueous binary solvolytic displacement behavior at the electrophilic carbonyl carbon was shown to be directly linked to both the type of alkyl group present, and to the dielectric constant of the participating solvents [13–34]. Conclusions for the majority of such solvolytic studies [19–24, 26–34], were obtained through detailed analyses procured when experimental kinetic rate data were incorporated into linear free energy relationships (LFERs), such as the extended Grunwald-Winstein (G-W) equation (equation 1) [35].

| (1) |

In equation 1, k and ko are the specific rates of solvolysis in a given solvent and in 80% ethanol (the standard solvent). The sensitivity to changes in solvent nucleophilicity (NT) are approximated by l, m represents the sensitivity to changes in the solvent ionizing power YCl, and c is a constant (residual) term. The NT scale developed for considerations of solvent nucleophilicity is based on the solvolyses of the S-methyldibenzothiophenium ion [36,37]. The solvent ionizing power YCl scale is based on the solvolysis of 1- or 2-adamantyl derivatives [38–42]. Equation 1 can also be applied to substitutions at an acyl carbon [43].

Whenever there is the possibility of the presence of charge delocalization due to anchimeric assistance resulting from 1,2-Wagner-Meerwein-type migrations or when, conjugated π-electrons are adjacent to the developing carbocationic center, an additional hI term [26,34,44–46] is added to the shown as equation 1, to give equation 2. In equation 2, h represents the sensitivity of solvolyses to changes in the aromatic ring parameter I [44–46].

| (2) |

In a recent review chapter [34], we discuss in detail, the equations 1 and 2 analyses obtained for several examples of alkyl, aryl, alkenyl, and alkynyl chloroformate solvolyses. All of the considerations [34] indicated the immense usefulness of equations 1 and 2. We have strongly suggested [26,34,43,47] that the l (1.66) and m (0.56) values (l/m ratio of 2.96) obtained for the solvolysis of phenyl chloroformate (PhOCOCl, 1) in the 49 solvents studied, be used as a standard indicator for chloroformate solvolysis pathways that incorporate a rate-determining formation of the tetrahedral intermediate in a carbonyl addition process (Scheme 1).

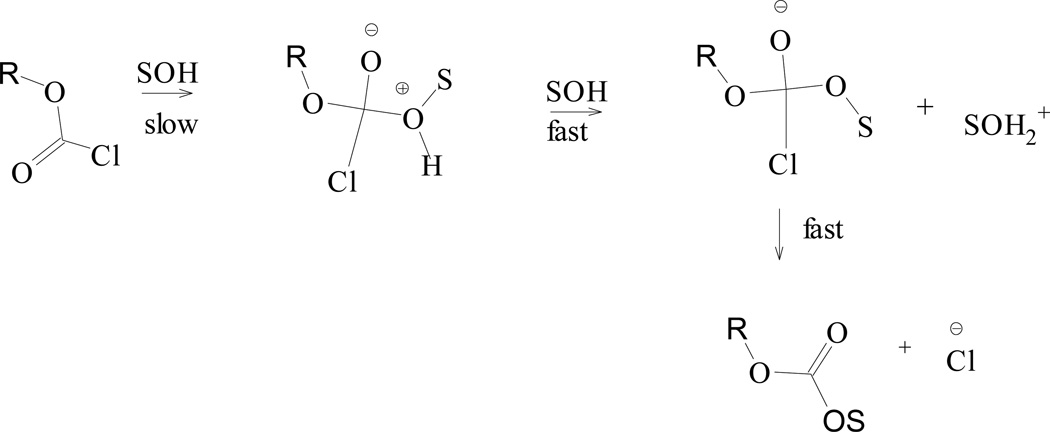

Scheme 1.

A carbonyl addition process for chloroformate esters

Substituting both oxygen atoms in 1 with sulfur, yields the dithioester phenyl chlorodithioformate (PhSCSCl, 2). Application of equations 1 and 2 to solvolytic rate data for 2 results in l values of 0.69 and 0.80, and m values of 0.95 and 1.02 [47,48], respectively. The l/m ratios (0.73 and 0.78) can be considered [26,33] as good indicators for ionization (SN1 type) mechanisms with significant solvation at the developing thioacylium ion. (or acylium ion in the case of the chloroformate analog) The accompanying h value of 0.42 obtained [47,48] for 2 (using equation 2), suggests that there is a minimal charge delocalization into the aromatic ring.

Scheme 2 depicts a simple probable ionization with the formation of an acyl cation. There is justifiable evidence [19,23,26,27,29,34] for a concerted solvolysis-decomposition process occurring, such that the cation involved in product formation is the alkyl cation.

Scheme 2.

A possible unimolecular solvolytic pathway for chloroformate esters

Likewise, several groups [9,16,17,25,28,32] have used kinetic solvent isotope effect (KSIE) studies to further probe the pseudo-first-order kinetic mechanisms of chloroformates and have provided very strong evidence, that the solvolysis of these substrates does include some general-base assistance (as indicated in Scheme 1). Our recent 2013 review chapter [34] documented the many methodical solvolytic investigations completed (to date) for structurally diverse alkyl, aryl, alkenyl, and alkynyl chloroformates. We showed that their solvolytic behavior varied between concurrent bimolecular addition-elimination (A-E) and unimolecular (SN1 type) ionization (or solvolysis-decomposition) pathways. The dominance of one pathway over the other was shown to be very strongly dependent on type of substrate employed, and on the solvent’s nucleophilicity and ionizing power ability [34 and references therein].

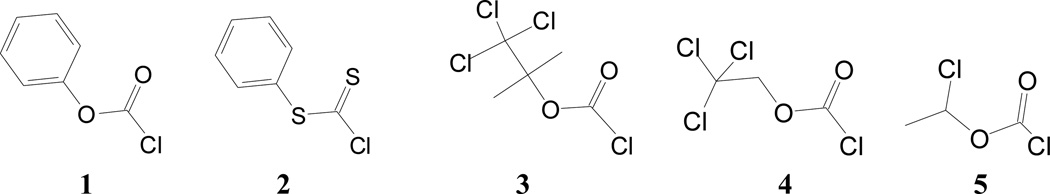

Common marketable β,β,β-trichloroalkyl chloroformates are, 2,2,2-trichloro-1-1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (3), and 2,2,2-trichloro-1-1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (4). A readily available and widely used α-chloro substituted chloroformate, is 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (5). All three compounds have substantial commercial use in peptide synthesis containing secondary and tertiary amines [49,50], as the carbamates developed for protection using these base-labile protection groups are easily cleaved by solvolysis [51].

Koh and Kang [28,32] followed the course of the solvolysis reactions in 3 and 4, by measuring the change in conductivity that occurred during the reaction. They used equation 1, to analyze the kinetic rate data for 3 and 4 and obtained l values of 1.42 and 1.34, and m values of 0.39 and 0.50 in 33 and 34 different mixed solvents respectively. Additionally, they obtained relatively large kinetic solvent isotope effects (kMeOH/kMeOD) of 2.14 and 2.39. Based on these experimental results, Koh and Kang [28,32] proposed a bimolecular SN2 mechanism for the two β,β,β-trichloroethyl chloroformate substrates (3 and 4). They stipulated that the mechanism had a transition-state (TS) where the bond-making component was more progressed, and based on their experimental kMeOH/kMeOD values, suggested that this SN2 TS is assisted by general-base catalysis. When the report of the Koh and Kang study of 3 appeared [28], the Wesley College undergraduate research group was independently following the rates of its reaction using a titrimetric method of analysis [52].

2. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

The 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (3, 96%, Sigma-Aldrich) and the 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (5, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich) were used as received. Solvents were purified as described previously [20]. For 3 and 5, a substrate concentration in the 0.003 – 0.009 M range in a variety of solvents was employed. For 3, the 25.0 mL binary solution mixtures were first allowed to equilibrate in a 35.0 °C constant-temperature water bath and then, the progress of the reaction was monitored by titrating aliquots of the solution using a lacmoid indicator. The rapid kinetic runs of 5 were followed using a conductivity cell containing 15 mL of solvent which was first allowed to equilibrate in a 25.0 °C constant-temperature water bath, with stirring. The specific rates and associated standard deviations, as presented in Table 1, are obtained by averaging all of the values from, at least, duplicate runs. Multiple regression analyses were carried out using the Excel 2007 package from the Microsoft Corporation. The molecular structures (syn geometry) presented in Figure 1, were drawn using the KnowItAll® Informatics System, ADME/Tox Edition, from BioRad Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA.

Table 1.

Specific rates of solvolysis (k) of 3 at 35.0 °C and 5 at 25.0 °C in several pure and binary solvents respectively. Also listed are the literature values for NT and YCl

| Solvent (%)a | 3; 104k, s−1b | 5; 104k, s−1b | NTc | YCld |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% EtOH | 6.49 ± 0.27 | 54.3 ± 0.8 | 0.37 | −2.50 |

| 90% EtOH | 7.24 ± 0.10 | 118 ± 3 | 0.16 | −0.90 |

| 80% EtOH | 8.18 ±0.11 | 226 ± 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 100% MeOH | 14.5 ± 0.6 | 509 ± 2 | 0.17 | −1.2 |

| 90% MeOH | 21.5 ± 0.1 | 682 ± 0 | −0.01 | −0.20 |

| 80% MeOH | 25.5 ± 0.2 | 953 ± 1 | −0.06 | 0.67 |

| 70% MeOH | 30.1 ± 0.7 | −0.40 | 1.46 | |

| 90% Acetone | 1.27 ± 0.07 | 3.62 ± 0.08 | −0.35 | −2.39 |

| 80% Acetone | 2.11 ± 0.09 | 18.1 ± 0.1 | −0.37 | −0.83 |

| 70% Acetone | 2.48 ± 0.08 | −0.42 | 0.17 | |

| 97% TFE (w/w) | 0.00217 ± 0.00022 | −3.30 | 2.83 | |

| 90% TFE (w/w) | 0.0150 ± 0.0009 | 0.215 ± 0.000 | −2.55 | 2.85 |

| 80% TFE (w/w) | 1.77 ± 0.01 | −2.19 | 2.90 | |

| 70% TFE (w/w) | 0.165 ± 0.009 | 3.09 ± 0.01 | −1.98 | 2.96 |

| 70T-30E | 0.0839 ± 0.0021 | −1.34 | 1.24 | |

| 60T-40E | 0.319 ± 0.007 | 2.59 ± 0.00 | −0.94 | 0.63 |

| 40T-60E | 10.2 ± 0.0 | −0.34 | −0.48 | |

| 20T-80E | 1.59 ± 0.17 | 0.08 | −1.42 | |

| 97% HFIP (w/w) | 0.00178 ± 0.00023 | −5.26 | 5.17 | |

| 90% HFIP (w/w) | 0.00273 ± 0.00021 | −3.84 | 4.41 | |

| 70% HFIP (w/w) | 0.0858 ± 0.0024 | −2.94 | 3.83 |

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of phenyl chloroformate (1), phenyl chlorodithioformate (2), 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (3), 2,2,2-trichloroethyl chloroformate (4), and 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (5)

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

In Table 1, we report the pseudo first order rate coefficients obtained for 3 at 35.0 °C, and for 5 at 25.0 °C, in 19 and 13 diverse binary aqueous organic solvents, respectively. Also presented in Table 1, are the NT and YCl values that are needed in equation 1 to compute the necessary bond-making (l value), bond-breaking (m value), and residual (c value) components.

The data in Table 1 shows that the specific rates of solvolysis of 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (3) gradually increases with the increase in water-content in ethanol (EtOH), methanol (MeOH), acetone, 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE), and 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluro-2-propanol (HFIP) mixtures. In the pure organic mixtures of 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol and ethanol (T-E), the rate increases with an increase in ethanol content. These broad observations on the solvent influences of the rate constants for 3 suggest that the solvent nucleophilic component (sensitivity indicated by l value) plays an important role in rate-determining step of the reaction. The experimental values of our rate determinations (for 3) are within an acceptable 2–10% range when compared to those obtained by Koh and Kang [28] in 60T-40E, and in the aqueous mixtures of ethanol, methanol, acetone, and TFE. However, in ethanol, methanol, 20T-80E and 70% HFIP at 35.0 °C, our results differed from the Koh and Kang [28] values by 15%, 18%, 33% and 61% respectively. In these four solvents, the rate data that we report in Table 1 are the average specific rates obtained after 4–8 different independent determinations; using different batches of solvents and containing multiple samples of varying concentrations of 3 that were purchased at different times. It is of utmost interest that the most significant deviations have occurred in solvents where sensitivity to general-base catalysis is the greatest. This is due to the solvents hydrogen-bond donating ability (typically in the order of HFIP > TFE > MeOH > water > ethanol) being a factor in the stabilizing of the developing transition-state [54].

For 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (5), the specific rate increase is much more pronounced with increases in the solvents nucleophilic ability (NT value). In the strongly hydrogen-bonding fluoroalcohols, we obtained rates in three aqueous TFE solutions and two TFE-EtOH mixtures, but were unable to obtain reliable and repeatable rates in the highly ionizing HFIP mixtures.

In Table 2, we list the specific rates of reaction for the previously examined primary and secondary alkyl chloroformates that follow similar mechanistic patterns in five common solvents at 25.0 °C. Included are methyl chloroformate (MeOCOCl) [21], ethyl chloroformate (EtOCOCl) [20], 2,2,2-trichloroethyl chloroformate (4) [32], n-propyl chloroformate (n-PrOCOCl) [24], iso-propyl chloroformate (i-PrOCOCl) [27], iso-butyl chloroformate (i-BuOCOCl) [30], and n-octyl chloroformate (n-OctOCOCl) [53]. Data for 3 and 5 are also shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

A comparison of the specific rates of solvolysis (105k, s−1) of methyl chloroformate (MeOCOCl) [21], ethyl chloroformte (EtOCOCl) [20], 3 [28], 4 [32], 5, n-propyl chloroformate (n-PrOCOCl) [24], iso-propyl chloroformate (i-PrOCOCl) [22,27], iso-butyl chloroformate (i-BuOCOCl) [30], and n-octyl chloroformate (n-OctOCOCl) [53] in common solvents at 25.0 °C

| Solvent (%) |

MeOCOCl | EtOCOCl | 3 | 4 | 5 | n-PrOCOCl | i-PrOCOCl | i-BuOCOCl | n-OctOCOCl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeOH | 15.6 | 8.24 | 85.7 | 605 | 5093 | 8.88 | 4.19 | 9.89 | 8.51 |

| EtOH | 3.51 | 2.26 | 25.8 | 231 | 543 | 2.20 | 1.09 | 2.36 | 2.39 |

| 80EtOH | 17.2 | 7.31 | 42.0 | 711 | 2264 | 7.92 | 3.92 | 8.17 | 7.37 |

| 97TFE | 0.023 | 0.062 | 12.3 | 0.086 | |||||

| 70TFE | 0.857 | 0.611 | 0.838 | 3.29 | 30.9 | 0.591 | 19.7 | 0.481 |

The 1-adamantyl and 2-adamantyl chloroformate (1-AdOCOCl and 2-AdOCOCl) [19,23] favor a solvolysis-decomposition type pathway in a majority of the solvents studied, and neopentyl chloroformate (neoPOCOCl) [29], whose mechanism parallels those listed in the non-fluoroalcohol mixtures, was studied at 45.0°C. Concurrent addition-elimination (A-E) and ionization mechansims were proposed for ethyl chloroformate (EtOCOCl) [20], with the ionization (SN1-type) pathway being favored in the highly ionizing fluoroalcohol mixtures. Additionally for the secondary chloroformate, i-PrOCOCl, a solvent-decomposition mechanism was shown to dominate in 70 TFE [27].

In MeOH, EtOH, and 80% EtOH, there is a 10 to 1000-fold increase in the rates of reaction with the introduction of chlorine at the α- or β-carbon of the primary alkyl chloroformate esters. This tendency for such compelling rate increases results from the inductive effects that are introduced due to the presence of electron-withdrawing chlorine (as substituents) on the primary alkyl chain.

For 3, 4, and 5, in the pure and aqueous alcohols, we observe the general progression of k5 ≫ k4 > k3. Such forceful advancements can only develop from the immense strength of the inductive effect present in 5, mainly due to the proximity of the electron withdrawing α-chloro substituent to the electrophilic reaction center. The k3 < k4 observations are due the additive steric and stereoelectronic effects introduced by the two methyl substituents on the α-carbon atom in 3.

In Table 3, we list the Grunwald-Winstein parameters obtained from the literature, for PhOCOCl [43,47], and the other pertinent alkyl chloroformates that are mentioned in this research article.

Table 3.

Correlation of the specific rates of solvolysis of 3, 4, and 5 (this study) and several other chloroformate esters (values from the literature), using the extended Grunwald-Winstein equation (equation 1)

| Substrate | na | lb | mb | cb | l/m | Rc | Fd | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhOCOCle | 49 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 2.95 | 0.980 | 568 | A-Ef |

| 2-AdOCOCle | 19 | 0.03 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | −0.10 ± 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.971 | 130 | Ig |

| 1-AdOCOCle | 11 | 0.08 ± 0.20 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.985 | 133 | Ig |

| MeOCOCle | 19 | 1.59 ± 0.09 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 2.74 | 0.977 | 171 | A-E |

| EtOCOCle | 28 | 1.56 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.24 | 2.84 | 0.967 | 179 | A-E |

| 7 | 0.69 ± 0.13 | 0.82 ± 0.16 | −2.40 ± 0.27 | 0.84 | 0.946 | 17 | SN1 | |

| n-PrOCOCle | 22 | 1.57 ± 0.12 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 2.79 | 0.947 | 83 | A-E |

| 6 | 0.40 ± 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.13 | −2.45 ± 0.27 | 0.63 | 0.942 | 11 | SN1 | |

| i-PrOCOCle | 9 | 1.35 ± 0.22 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 3.38 | 0.960 | 35 | A-E |

| 16 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | −0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.982 | 176 | Ig | |

| i-BuOCOCle | 18 | 1.82 ± 0.15 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 3.43 | 0.957 | 82 | A-E |

| neoPOCOCle | 13 | 1.76 ± 0.14 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 3.67 | 0.977 | 226 | A-E |

| 8 | 0.36 ± 0.10 | 0.81 ± 0.14 | −2.79 ± 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.938 | 18 | SN1 | |

| PhSCSCle | 31 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.987 | 521 | SN1 |

| 3 | 18h | 1.43 ± 0.15 | 0.38 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.13 | 3.76 | 0.963 | 96 | A-E |

| 4 | 32i | 1.52 ± 0.08 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 2.76 | 0.962 | 178 | A-E |

| 5 | 13 | 1.99 ± 0.23 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 0.19 ± 0.17 | 3.21 | 0.953 | 49 | A-E |

n is the number of solvents.

With associated standard error.

Multiple Correlation Coefficient.

F-test value.

See text for references giving the source of this data.

Addition-elimination.

Ionization-fragmentation.

No 97 HFIP.

No 90 HFIP, 90 TFE.

In order to interpret detailed mechanisms of reaction for 3, 4, and 5, we have also reanalyzed and documented the resultant multiple regression values that were obtained on using equation 1. For use as a mechanistic criterion, we also considered the l/m ratios of the cataloged chloroformate substrates, since it was convincingly shown [53] that n-octyl fluoroformate, which has an l/m ratio of 2.28, proceeds by a rate-determining carbonyl-addition (A-E) process. This assignment was supported by the observation that in a number of common solvents the kF/kCl ratios for n-octyl fluroformate and n-octyl chloroformate was greater than unity [53].

Our solvolysis study for 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (3) at 35.0 °C, included 19 solvents that had very widely varying ranges of solvent nucleophilicity and solvent ionizing power. Analyses (using equation 1) of the rates obtained for 3 in these solvents resulted in an l value of 1.17 ± 0.17, an m value of 0.29 ± 0.13, a c value of 0.03 ± 0.16, an F-test value of 67, and a multiple correlation coefficient (R) value of 0.945. These l an m values are on the much lower side of the spectrum when compared to those tabulated in Table 3 for the previously studied alkyl chloroformate esters. Furthermore, the m value obtained for 3 has a P value (probability of statistical significance) of 0.03. Using literature values [43,47] for PhOCOCl, in the same 19 solvents (and using an interpolated rate of 1.49 × 10−4s−1 for PhOCOCl in 70T-30E), we obtained, 1.62 ± 0.11, 0.54 ± 0.08, 0.24 ± 0.11, 229, and 0.983, for l, m, c, F-test, and R, respectively.

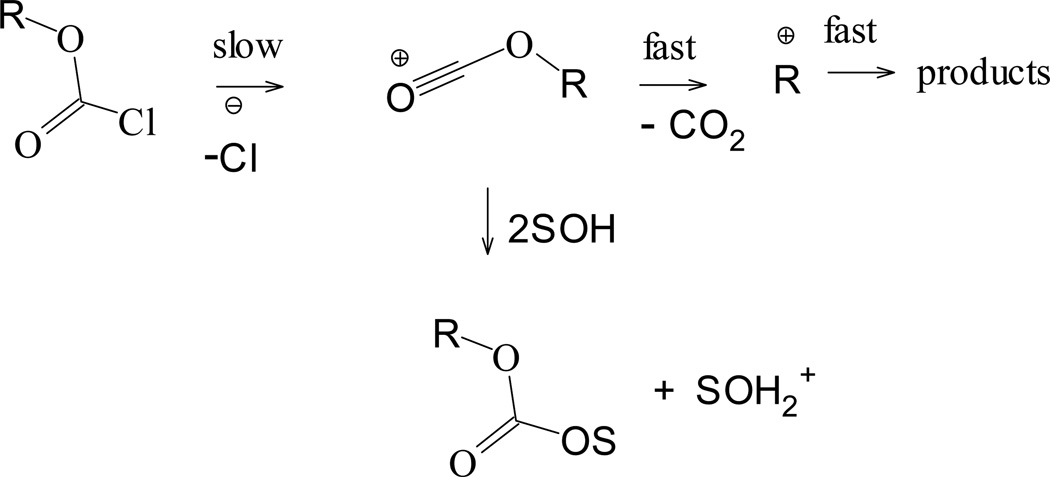

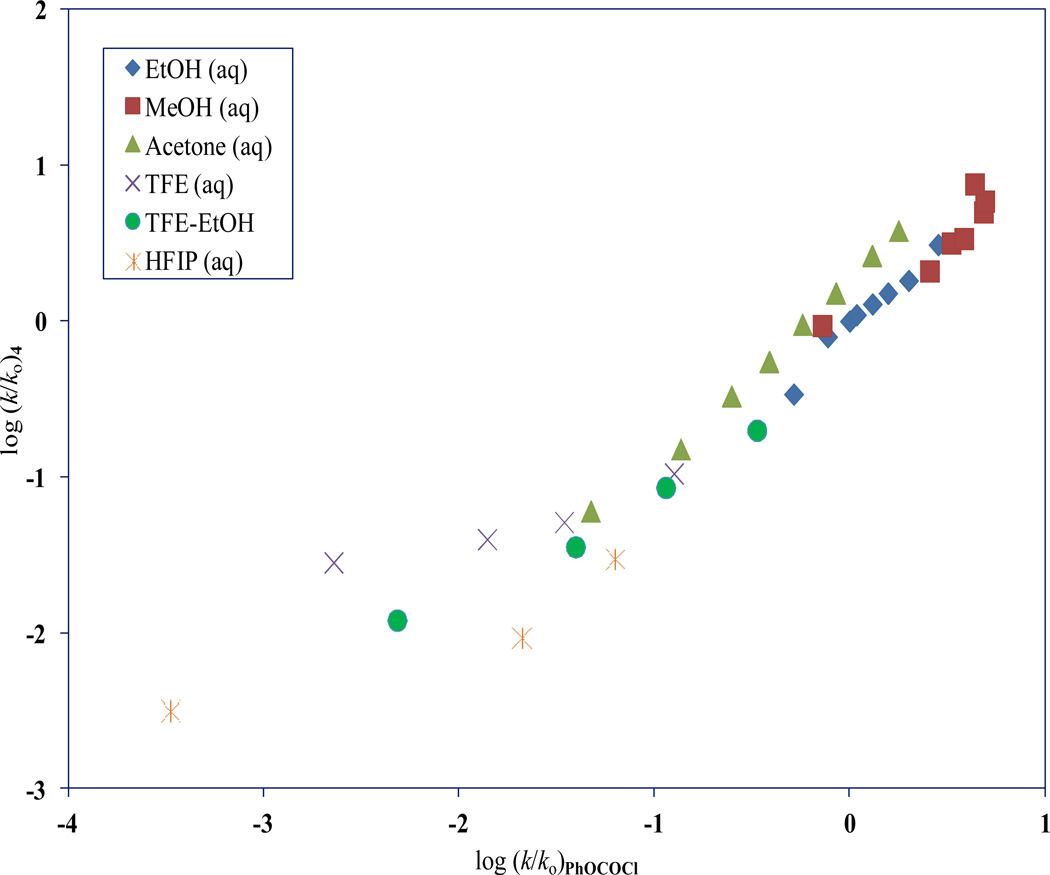

A plot of the log (k/ko)3 versus log (k/ko)PhOCOCl is shown in Figure 2. This graph has a slope of 0.831 ± 0.058, an intercept of −0.099 ± 0.118, an F-test value of 204, and a best-fit linear regression (r2) value of 0.961. The Figure 2 residual plot clearly shows that the 97 HFIP point deviates significantly from the best-fit line. Removal of this 97 HFIP value results in a slope of 0.988 ± 0.002, an intercept of −0.002 ± 0.073, an improved F-test value of 483, and an enhanced r2 value of 0.984. Such improvements strongly illustrate that for 3, a similar PhOCOCl addition-elimination (A-E) type mechanism (Scheme 1) occurs in the remaining 18 solvents.

Figure 2.

The plot of log (k/ko)3 against log (k/ko)PhOCOCl

On omitting the 97 HFIP rate value for 3 and reanalyzing the remaining 18 solvents (Table 1) with equation 1, we obtain an l value of 1.43 ± 0.15, an m value of 0.38 ± 0.10 (associated P value = 0.002), a c value of 0.17 ± 0.13, F-test = 96, and R = 0.963 (reported in Table 3). Here, 3 has an l/m ratio of 3.76. In the identical 18 solvents studied, a reanalysis (with equation1) for PhOCOCl leads to values of 1.61 ± 0.13, 0.53 ± 0.09, and 0.23 ± 0.12, for l, m, and c, respectively. The l/m ratio for PhOCOCl is 3.04. These robust l and m values obtained for PhOCOCl, have an associated F-test value of 127 and R = 0.972. The larger l/m ratio for 3 indicates that it is more susceptible (when compared to PhOCOCl) to general-base catalysis.

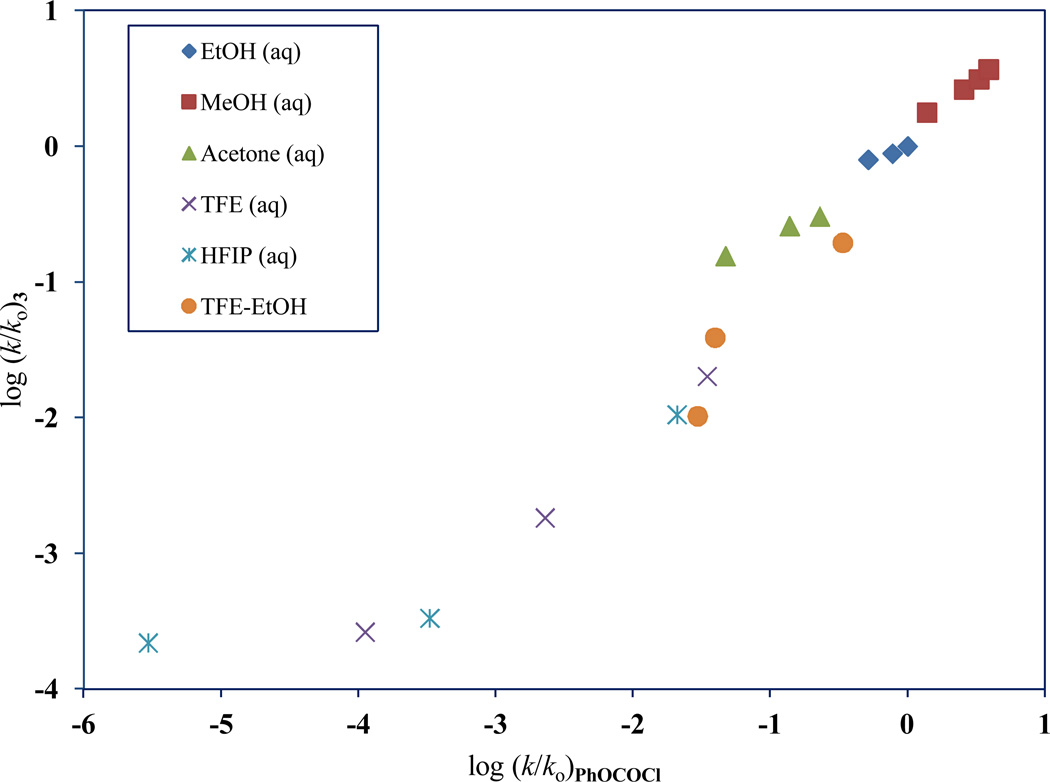

A plot of log (k/ko) for 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (3) against 1.43 NT + 0.38 YCl is shown in Figure 3 with the deviation for the 97 HFIP point indicated. Using log (k/ko)3 = 1.43 NT + 0.38 YCl + 0.17, we calculated an expected bimolecular carbonyl-addition rate for 3 to be 3.35 × 10−9 in 97 HFIP. Comparing this calculated value to the experimental value obtained for 3 in 97 HFIP (and shown in Table 1), we can definitively conclude that in this highly ionizing mixture, the mechanism of reaction is of the SN1 type, with 98% of reaction following the ionization pathway.

Figure 3.

The plot of log (k/ko) for 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chlorothioformate (3) against 1.43 NT + 0.38 YCl in nineteen pure and binary solvents. The 97 HFIP point was not included in the correlation. It is added to the plot to show the extent of its deviation

Koh and Kang [32] measured the rate constants for solvolyses of 2,2,2-trichloroethyl chloroformate (4) in 34 pure and binary solvent mixtures at 35.0 °C. Using their data [32], we reanalyzed the reported rates of reaction using equation 1 and obtained, l = 1.35 ± 0.07, m = 0.51 ± 0.04, c = 0.07 ± 0.06, F-test = 175, and R = 0.958. Our l and m values match the ones reported [32] for 4. The l/m ratio for 4 works out to be 2.65. Analyzing the literature data for PhOCOCl [43,47] in the identical 34 solvents, we obtain, l = 1.52 ± 0.08, m = 0.52 ± 0.04, c = 0.11 ± 0.07, F-test = 188, and R = 0.961 (l/m ratio = 2.92).

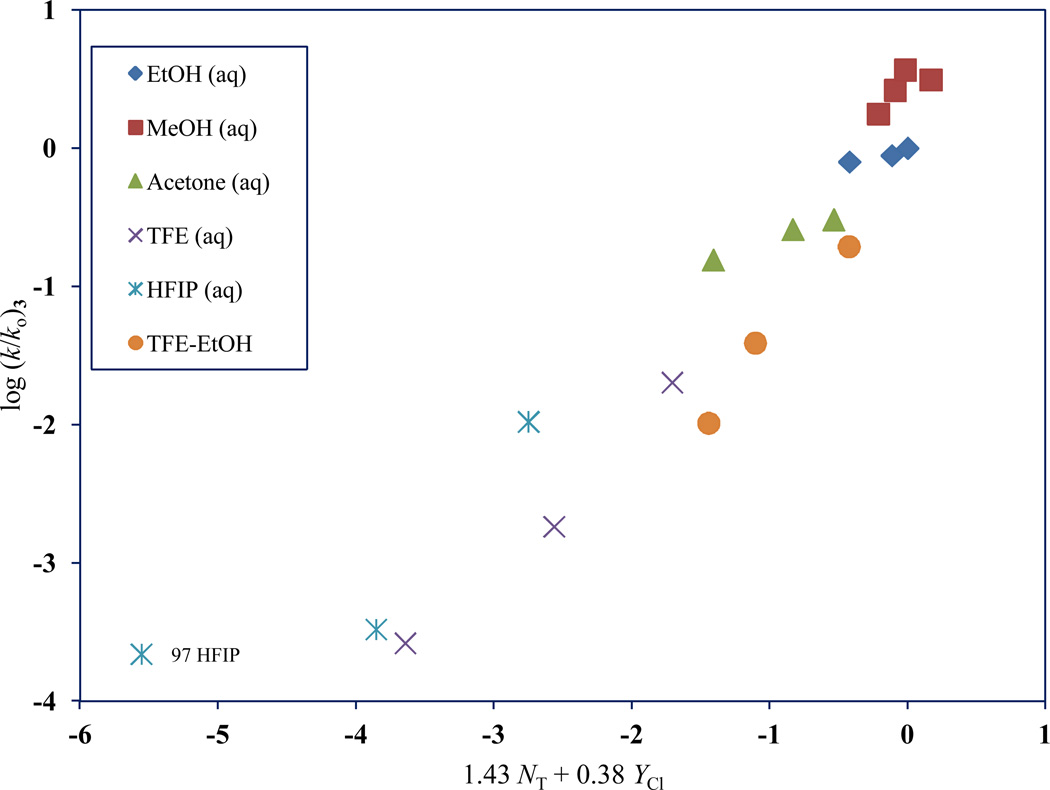

A plot of log (k/ko)4 versus log (k/ko)PhOCOCl is shown in Figure 4. This plot has a slope = 0.85 ± 0.04, c = 0.03 ± 0.05, F-test = 374, and r2 = 0.960. A visual inspection of the scatter plot (Figure 4) reveals that the 90 HFIP and 90 TFE points are markedly dispersed. The removal of these two points increases the F-test value to 554 and the r2 value rises to 0.974. The slope is now 0.99 ± 0.04, and c = 0.04 ± 0.04. The improved r2 value hints that the two substrates (4 and PhOCOCl) proceed via similar mechanisms in the remaining 32 solvents.

Figure 4.

The plot of log (k/ko)4 against log (k/ko)PhOCOCl

An analysis (Table 3) using equation 1 for 4 in the remaining 32 solvents yields, l = 1.52 ± 0.08, m = 0.55 ± 0.03, c = 0.01 ± 0.06, F-test = 178, and R = 0.962. In corresponding solvents for PhOCOCl, an analysis using equation 1, produces l = 1.47 ± 0.10, m = 0.51 ± 0.04, c = 0.10 ± 0.07, F-test = 105, and R = 0.938. The l/m ratio for 4 is 2.76 and that for PhOCOCl is 2.88, thus illustrating that solvolyses of both 4 and PhOCOCl proceed through very similar carbonyl-addition tetrahedral transition-state.

Using log (k/ko)4 = 1.52NT + 0.55YCl + 0.01, we calculated the expected bimolecular carbonyl-addition (A-E) rates for 90 HFIP and 90 TFE to be 4.90 × 10−6 s−1 and 6.19 × 10−5 s−1. Comparing these calculated rates to the ones that were experimentally determined in 90 HFIP and 90 TFE [32], we project that the ionization (SN1) component for 4 in these two solvents are, 87% and 82% respectively.

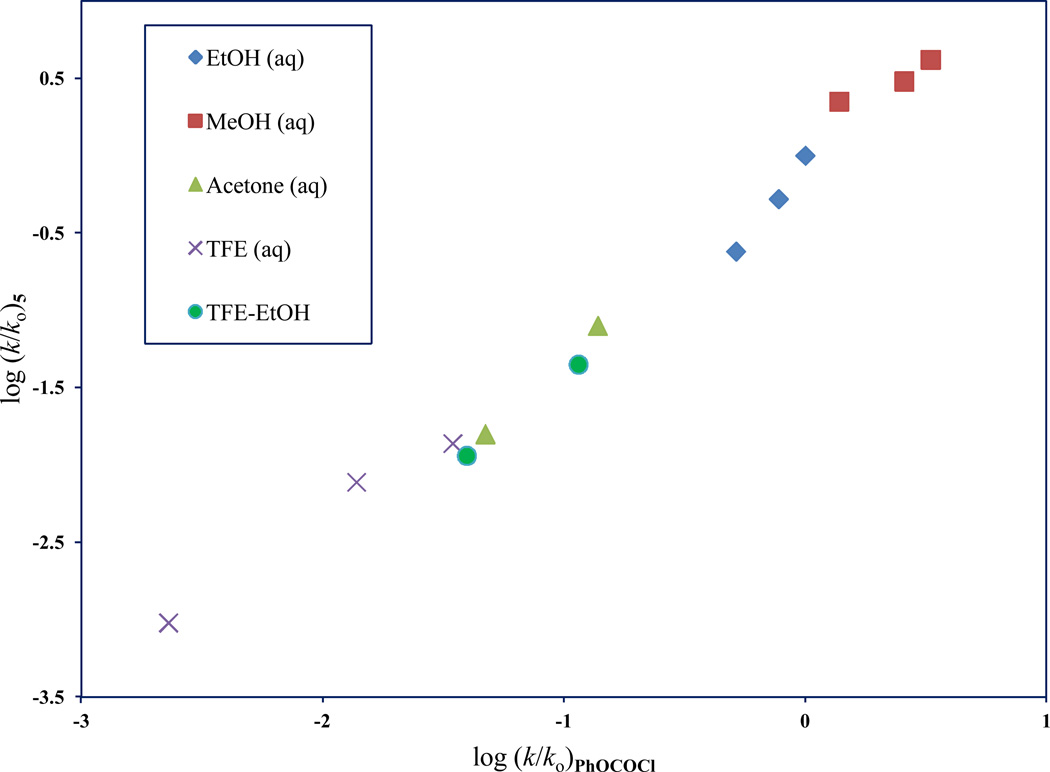

Due to a variety of experimental difficulties we could only study the solvolysis of the monochloro substrate, 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (5), in 13 pure and aqueous binary mixtures at 25.0 °C. A plot of log (k/ko)5 against log (k/ko)PhOCOCl is shown in Figure 5. This plot has a slope of 1.19 ± 0.05, an intercept of −0.07 ± 0.06, an F-test value of 603, and an r2 value of 0.991. The considerable F-test value accompanied by an excellent r2 value, indicates that this is indeed a well-fitting regression model, and that the two substrates (PhOCOCl and 5) have very similar transition-state character. The slightly greater than unity slope further suggests that 5 has a slightly later transition-state (as compared to PhOCOCl).

Figure 5.

The plot of log (k/ko)5 against log (k/ko)PhOCOCl

For 5 an analysis using equation 1 of solvolyses rates in all of the thirteen solvents studied, results in l = 1.99 ± 0.23, m = 0.62 ± 0.12, c = 0.19 ± 0.17, F-test = 49, and R = 0.953. The l/m ratio is 3.21 for 5. In the identical thirteen solvents, an equation 1 analysis for PhOCOCl yields, l = 1.61 ± 0.15, m = 0.47 ± 0.08, c = 0.19 ± 0.11, F-test = 90, R = 0.973, and the l/m ratio = 3.42. A comparison of the l/m ratios for these two substrates again illustrates the similarities in the tetrahedral addition-elimination transition-states.

4. CONCLUSION

The interplay between electronic and steric effects amongst the three chloro-substituted chloroformates studied, is clearly evident in the rate order k5 ≫ k4 > k3 observed. The α-chloro-substituent in 1-chloroethyl chloroformate (5) exerts very large electron-withdrawing inductive effects and, as a result, it leads to rates of reaction that are orders of magnitude higher. The presence of the electron-withdrawing trichloromethyl group in 2,2,2-trichloroethyl chloroformate (4) also plays an advantageous role in accelerating the addition step of an addition-elimination reaction, whereas the comparatively sterically encumbered 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate (3), had the lowest rates that were influenced by counteractive electronic and steric effects.

Coupling theories of linear-free energy relationships (LFERs) that employ a similarity-model approach based on the solvolysis of phenyl chloroformate (1), together with the information derived from the extended Grunwald-Winstein (equation 1) analysis, present a consistent picture for the solvolysis mechanisms of 3, 4, and 5.

A log (k/ko) plot of 3 against 1, reveals a large-scale divergence for the 97 HFIP point. Neglecting this 97 HFIP data point for 3 in the Grunwald-Winstein computation, led to an l/m ratio of 3.76, which is solidly indicative of a carbonyl-addition process that is assisted by general-base catalysis. This also indicates that the ionization pathway is the dominant process (98%) for 3 in 97 HFIP.

Utilizing the previously published rates, a log (k/ko) plot of 4 against 1, displayed some disparity in the 90 HFIP and 90 TFE values. On their removal and then applying the equation 1 to the rates in the remaining 32 solvents, we acquired an l/m ratio of 2.76 for 4, which was found to be very close to the 2.88 value for 1 in identical solvents. This supports our proposal that the tetrahedral carbonyl-addition transition-state 4 is analogous to that of 1.

The log (k/ko) plot of 5 against 1 was near ideal, with an r2 value of 0.991, and a slope that was slightly greater than unity. The similar l/m ratios for 5 and 1 verified that the two substrates had virtually indistinguishable tetrahedral transition-state structure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this peer-reviewed article was supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS-NIH) under grant number P20GM103446-13 (DE-INBRE grant); the National Science Foundation (NSF) EPSCoR Grant No. IIA-1301765 (DE-EPSCoR); the State of Delaware; and an NSF ARI-R2 grant 0960503. The DE-INBRE and DE-EPSCoR grants were obtained under the leadership of the University of Delaware, and the authors sincerely appreciate their efforts.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Matzner M, Kurkjy RP, Cotter RJ. The Chemistry of Chloroformates. Chemical Reviews. 1964;64:645–687. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kevill DN. Chloroformate Esters and Related Compounds. In: Patai S, editor. The Chemistry of the Functional Groups: The Chemistry of Acyl Halides. Chapter 12. New York, NY, USA: Wiley; 1972. pp. 381–453. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreutzberger CB. Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2001. Chloroformates and Carbonates. ISBN 9780471238966. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbicide Report. Chemistry and analysis. Environmental Effects. Agricultural and other applied uses. Washington, DC, USA: Report by Hazardous Materials Advisory Committee, United States Environmental Agency Science Advisory Board; 1974. May, [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parrish JP, Salvatore RN, Jung KW. Perspectives of alkyl carbonates in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2000:8207–8237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottalico D, Fiandanese V, Marchese G, Punzi A. A New Versatile Synthesis of Esters from Grignard Reagents and Chloroformates. Synlett. 2007;6:974–976. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee SS, Aher N, Patel R, Khandare J. Poly(ethylene glycol)-prodrug Conjugates: Concepts, Design, and Application. J. Drug Delivery. 2012:17. doi: 10.1155/2012/103973. Article ID: 103973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee I. Nucleophilic Substitution at a Carbonyl Carbon Atom. Part II. CNDO/2 Studies on Conformation and Reactivity of the Thio-Analogues of the Thio-Analogues of Methyl Chloroformate. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1972;16:334–340. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentley TW, Harris HC, Ryu ZH, Lim GT, Sung DD, Szajda SR. Mechanisms of Solvolyses of Acid Chlorides and Chloroformates. Chloroacetyl and Phenylacetyl Chloride as Similarity Models. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:8963–8970. doi: 10.1021/jo0514366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvatore RN, Yoon CH, Jung KW. Synthesis of Secondary Amines. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:7785–7811. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeom C-E, Kim YJ, Lee SY, Shin YJ, Kim BM. Efficient Chemoselective Deprotection of Silyl Ethers Using Catalytic 1-Chloroethyl Chloroformate in Methanol. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:12227–12237. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heller ST, Schultz EE, Sarpong R. Chemoselective N-Acylation of Indoles and Oxazolidinones with Carbonylazoles. Angewandte Chemie Int. Ed. 2012;51:8304–8308. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Queen A. Kinetics of the Hydrolysis of Acyl Chlorides in Pure Water. Can. J. Chem. 1967;45:1619–1629. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crunden EW, Hudson RF. The Mechanism of Hydrolysis of Acid Chlorides. Part VII. Alkyl Chloroformates. J. Chem. Soc. 1961:3748–3755. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green M, Hudson RF. The Mechanism of Hydrolysis of Acid Chlorides. Part VIII. Chloroformates of Secondary Alcohols. J. Chem. Soc. 1962:1076–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 16.La S, Koh KS, Lee I. Nucleophilic Substitution at a Carbonyl Carbon Atom (XI). Solvolysis of Methyl Chloroformate and its Thioanalogues in Methanol, Ethanol and Ethanol-Water Mixtures. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1980;24:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.La S, Koh KS, Lee I. Nucleophilic Substitutions at a Carbonyl Carbon Atom (XII). Solvolysis of Methyl Chloroformate and its Thioanalogues in CH3CN-H2O and CH3COCH3-H2O Mixtures. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 1980;24:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlov SI, Chimishkyan AL, Grabarnik MS. Kinetic Relationships Governing the Ethanolysis of Halogenoformates. J. Org. Chem. USSR (Engl. Transl.) 1983;19:1981–1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kevill DN, Kyong JB, Weitl FL. Solvolysis-Decomposition of 1-Adamantyl Chloroformate: Evidence for Ion Pair Return in 1-Adamantyl Chloride Solvolysis. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4304–4311. doi: 10.1021/jo0207426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Concerning the Two Reaction Channels for the Solvolyses of Ethyl Chloroformate and Ethyl Chlorothioformate. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:2120–2124. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kevill DN, Kim JC, Kyong JB. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Methyl Chloroformate with Solvent Properties. J. Chem. Res. Synop. 1999:150–151. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyong JB, Kim YG, Kim DK, Kevill DN. Dual Pathways in the Solvolyses of Isopropyl Chloroformate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000;21:662–664. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyong JB, Yoo JS, Kevill DN. Solvolysis-Decomposition of 2-Adamantyl Chloroformate: Evidence for Two Reaction Pathways. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:3425–3432. doi: 10.1021/jo0207426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyong JB, Won H, Kevill DN. Application of the Extended Grunwald-Winstein Equation to Solvolyses of n-Propyl Chloroformate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2005;6:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentley TW. Structural Effects on the Solvolytic Reactivity of Carboxylic and Sulfonic Acid Chlorides. Comparisons with Gas-Phase Data for Cation Formation. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:6251–6257. doi: 10.1021/jo800841g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Sixty years of the Grunwald-Winstein Equation: Development and Recent Applications. J. Chem. Res. 2008;2008:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Souza MJ, Reed DN, Erdman KJ, Kevill DN. Grunwald-Winstein Analysis–Isopropyl Chloroformate Solvolysis Revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009;10:862–879. doi: 10.3390/ijms10030862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koh HJ, Kang SJ, Kevill DN. Kinetic Studies of the Solvolyses of 2,2,2-Trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl Chloroformate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2010;31:835–839. [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Souza MJ, Carter SE, Kevill DN. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Neopentyl Chloroformate—A Recommended Protecting Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:1161–1174. doi: 10.3390/ijms12021161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Souza MJ, McAneny MJ, Kevill DN, Kyong JB, Choi SH. Kinetic Evaluation of the Solvolysis of Isobutyl Chloro-and Chlorothioformate Esters. Beilstein. J. Org. Chem. 2011;7:543–552. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park KH, Lee Y, Lee YW, Kyong JB, Kevill DN. Rate and Product Studies of 1-Adamantylmethyl Haloformates Under Solvolytic Conditions. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2012;33:3657–3664. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh HJ, Kang SJ. Correlation of the Rates on Solvolysis of 2,2,2-Trichloroethyl Chloroformate using the Extended Grunwald-Winstein Equation. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2012;33:1729–1733. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim GT, Lee YH, Ryu ZH. Further Kinetic Studies of Solvolytic Reactions of Isobutyl Chloroformate in Solvents of High Ionizing Power Under Conductometric Conditions. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2013;34:615–621. [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Souza MJ, Kevill DN. Application of the Grunwald-Winstein Equations to Studies of Solvolytic Reactions of Chloroformate and Fluoroformate Esters. Recent Res. Devel. Organic Chem. 2013;13:1–38. and references there in. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winstein S, Grunwald E, Jones HW. The Correlation of Solvolyses Rates and the Classification of Solvolysis Reactions into Mechanistic Categories. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951;73:2700–2707. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kevill DN, Anderson SW. An Improved Scale of Solvent Nucleophilicity Based on the Solvolysis of the S-Methyldibenzothiophenium Ion. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:1845–1850. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kevill DN. Development and Uses of Scales of Solvent Nucleophilicity. In: Charton M, editor. Advances in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships. Volume 1. Greenwich, CT, USA: JAI Press; 1996. pp. 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bentley TW, Carter GE. The SN2-SN1 Spectrum. 4. Mechanism for Solvolyses of tert-Butyl Chloride: A Revised Y Scale of Solvent Ionizing Power based on Solvolyses of 1-Adamantyl Chloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5741–5747. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bentley TW, Llewellyn G. Yx Scales of Solvent Ionizing Power. Prog. Phys. Org. Chem. 1990;17:121–158. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Additional YCl Values and Correlation of the Specific Rates of Solvolysis of tert-Butyl Chloride in Terms of NT and YCl Scales. J. Chem. Res. Synop. 1993:174–175. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lomas JS, D’Souza MJ, Kevill DN. Extremely Large Acceleration of the Solvolysis of 1-Adamantyl Chloride upon Incorporation of a Spiro Adamantane Substituent: Solvolysis of 1-Chlorospiro[adamantane 2, 2'-adamantane] J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5891–5892. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kevill DN, Ryu ZH. Additional solvent ionizing power values for binary water-1,1,1,3,3,3,-hexafluoro-2-propanol solvents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2006;7:451–455. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Phenyl Chloroformate. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1997:1721–1724. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kevill DN, Ismail NHJ, D’Souza MJ. Solvolysis of the (p-Methoxybenzyl)dimethylsulfonium Ion. Development and Use of a Scale to Correct for Dispersion in Grunwald-Winstein Plots. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:6303–6312. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Use of the Simple and Extended Grunwald-Winstein Equations in the Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Highly Hindered Tertiary Alkyl Derivatives. Cur. Org. Chem. 2010;14:1037–1049. doi: 10.2174/138527210791130505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kevill DN, Park YH, Park BC, D’Souza MJ. Nucleophilic Participation in the Solvolyses of (Arylthio) methyl Chlorides and Derivatives: Application of Simple and Extended Forms of the Grunwald-Winstein Equations. Cur. Org. Chem. 2012;16:1502–1511. doi: 10.2174/138527212800672592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kevill DN, Koyoshi F, D’Souza MJ. Correlation of the Specific Rates of Solvolysis of Aromatic Carbamoyl Chlorides, Chloroformates, Chlorothionoformates, and Chlorodithioformates Revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007;8:346–352. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Phenyl Chlorothionoformate and Phenyl Chlorodithioformate. Can. J. Chem. 1999;77:1118–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 49.He X-S, Brossi A. Di-(2,2,2-Trichloroethyl)-Carbonate: Byproduct in Reactions with 2,2,2-Trichloroethyl Chloroformate. Syn. Commun. 1990;20:2177–2179. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olofson RA. New, Useful Reactions of Novel Haloformates and Related Reagents. Pure & Appl. Chem. 1998;60:1715–1724. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto K, Takemae M. The Utility of t-Butyldimethylsilane as an Effective Silylation Reagent for the Protection of Functional Groups. Bull. Chem. Soc. Japan. 1989;62:2111–2113. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandosky B, D'Souza MJ, Kevill DN. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society (Vol. 241) Vol. 1155. 16th ST, NW, Washington, DC 20036 USA: 2011. Mar, Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of 2,2,2-Trichloro-1,1,-Dimethylethyl Chloroformate. Abstract #833, Division of Chemical Education (CHED) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kevill DN, D’Souza MJ. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of n-Octyl Fluoroformate and a Comparison with n-Octyl Chloroformate Solvolysis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 2. 2002;2:240–243. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Byers JA, Jamison TF. Entropic Factors Provide Unusual Reactivity and Selectivity in Epoxide-Opening Reactions Promoted by Water. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:16724–16729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311133110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]