Abstract

Background

Despite being characterized primarily by disturbances in eating behavior, relatively little is known about specific eating behaviors in anorexia nervosa (AN) and how they relate to different emotional, behavioral, and environmental features.

Methods

Women with AN (n=118) completed a 2-week ecological momentary assessment (EMA) protocol during which they reported on daily eating- and mood-related patterns. Latent profile analysis was used to identify classes of eating episodes based on the presence or absence of the following indicators: loss of control; overeating; eating by oneself; food avoidance; and dietary restraint.

Results

The best-fitting model supported a 5-class solution: avoidant eating; solitary eating; binge eating; restrictive eating; and loss of control eating. The loss of control and binge eating classes were characterized by high levels of concurrent negative affect and a greater likelihood of engaging in compensatory behaviors. The restrictive eating class was associated with the greatest number of concurrently-reported stressful events, while the avoidant and solitary eating episode classes were characterized by relatively few accompanying stressful events. Body checking was least likely to occur in conjunction with restrictive eating behaviors.

Conclusions

Results support the presence of discrete types of eating episodes in AN that are associated with varying degrees of negative affect, stress, and behavioral features of eating disorders. Loss of control and dietary restriction may serve distinct functional purposes in AN, as highlighted by their differing associations with negative affect and stress. Clinical interventions for AN may benefit from targeting functional aspects of eating behavior among those with the disorder.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, eating behavior, ecological momentary assessment, negative affect, binge eating, dietary restriction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious psychiatric illness associated with significant medical and psychosocial comorbidities (Hudson et al., 2007; Pomeroy et al., 2002). AN is characterized primarily by disturbances in eating behavior, particularly restriction of energy intake relative to one’s energy needs (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), yet relatively little is known about specific eating patterns in AN. With regard to typical eating behaviors in AN, evidence suggests that individuals with the disorder tend to consume fewer kilocalories and less fat than healthy controls when under observation in controlled laboratory conditions (Fernstrom et al., 1994; Gwirtsman et al., 1989; Hadigan et al., 2000; Mayer et al., 2012; Sysko et al., 2005). However, results from one study that collected data via daily dietary recall based on ecological momentary assessment, or EMA (which addresses concerns about the artificial nature of the laboratory setting by collecting data in “real time” in the natural environment; Shiffman et al., 2008), suggest that the mean daily caloric intake of individuals with AN may be closer to nutritional recommendations than one might expect based on laboratory data (Burd et al., 2009). The extent to which this discrepancy is due to over-reporting in EMA, reactivity associated with laboratory conditions that results in reduced energy consumption, or some combination thereof is unclear. Nevertheless, given that existing psychological treatments of AN have thus far shown limited efficacy (Wilson et al., 2007), a better understanding of the context and associated features of eating episodes in AN could inform the development of more effective interventions for the disorder.

It has been proposed that eating disorder behaviors in AN are learned habits that become well-entrenched since they are persistently reinforced over time (Walsh, 2013). One hypothesized means of reinforcement may be via a reduction in negative affect that occurs subsequent to the behaviors. Self-report questionnaire data suggest that individuals with AN have difficulties tolerating negative emotions (Hambrook et al., 2011; Harrison et al., 2009; Wildes et al., 2010), and that such difficulties may play a role in the occurrence of eating disorder behaviors (Espeset et al., 2012; Racine et al., in press). Similarly, both laboratory data (Steinglass et al., 2010; Wildes et al., 2012) and previous EMA data reported by our group (Engel et al., 2013; Engel et al., 2005; Lavender et al., 2013a) have indicated that negative affect (and anxiety in particular) is associated with subsequent eating disorder cognitions and behaviors, including dietary restriction, binge eating and purging, and body checking. In spite of this apparent link between negative affect and eating patterns, it is currently unclear whether distinct emotional or behavioral cues are associated with different types of eating behaviors in AN.

The purpose of the current study was twofold: 1) to identify classes of eating episodes reported in the natural environment by women with AN using an empirical classification approach; and 2) to examine the emotional and behavioral context in which these classes of eating episodes occur. A secondary aim was to examine the extent to which AN diagnostic subtypes (i.e., restricting type versus binge eating/purging type) differ with respect to self-reported frequencies of different classes of eating episodes. We hypothesized that distinct classes of eating episodes would be identified, characterized by varying combinations of loss of control while eating, overeating, eating by oneself, avoiding certain foods, and restricting food intake. In particular, we expected that classes of eating episodes involving loss of control and/or overeating would be associated with high levels of negative affect, consistent with the previous literature (Haedt-Matt et al., 2011). Conversely, classes of eating episodes involving restricted eating or food avoidance were expected to be associated with an increased likelihood of engaging in body checking and related behaviors (Lavender et al., 2013b), which may function as a method of reaffirming the effectiveness of restrictive behaviors. Finally, we expected that individuals with AN binge/purge subtype would be more likely to endorse the classes of eating episodes characterized by loss of control and/or overeating than individuals with AN restricting subtype.

METHODS

Participants

Eligible participants were at least 18 years old, female, and met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for AN or sub-threshold AN. Sub-threshold AN was defined as meeting all of the DSM-IV criteria for AN except: (1) having a body mass index (BMI; m/kg2) between 17.6 and 18.5; or (2) either amenorrhea or body image disturbance and intense fear of fat. Based on these criteria, 121 participants met eligibility criteria, consented, and were enrolled. Three participants had EMA compliance rates of less than 50% and their data were not included in the final analyses, resulting in a total of 118 participants. Participants were 25.3±8.4 years old, on average (range=18–58 years), with a mean body mass index of 17.2±1.0 kg/m2 (range=13.4–18.5). Participants were predominantly Caucasian (96.6%), single (75.4%), and most (90.7%) had at least some college education. A total of 73 (61.9%) participants met criteria for AN restricting subtype, while 45 (38.1%) met criteria for AN binge/purge subtype.

Procedures

Participants were recruited at three sites across the Midwest (Fargo, ND; Minneapolis, MN; Chicago, IL) from various clinical (e.g., mailings to eating disorder treatment professionals) and community sources (e.g., community and campus advertisements). Institutional review board approval for the study was obtained at each site.

Potential participants were initially screened by phone, and those appearing to meet eligibility criteria were invited to attend an informational meeting at which they received further information regarding the study and provided written informed consent. Participants were then scheduled for two assessment visits during which they were assessed for medical stability, and completed self-report questionnaires and structured interviews.

During one of the initial assessment visits, a research assistant trained participants on how to use the palmtop computers for the EMA protocol. Participants were instructed to complete assessments of mood and behavior for three types of recordings: 1) event-contingent recordings, in which they completed assessments after any eating episodes (including binge eating) or AN behaviors (i.e., vomiting, using laxatives for weight control, weighing oneself, exercising, skipping a meal, or drinking fluids to curb appetite) at the time of occurrence; 2) interval-contingent recordings, in which they completed assessments nightly before bedtime; and 3) signal-contingent recordings, in which they completed assessments in response to 6 semi-random prompts by investigators occurring every 2–3 hours between 8:00am and 10:00pm (Wheeler et al., 1991). Participants carried the palmtop computer for two practice days to increase familiarity with the protocol and minimize reactivity. Participants then returned to the research center and provided the data recorded during their practice period, which were not used in analyses. A research assistant reviewed the practice data and gave participants feedback regarding compliance and data quality. Participants were then given the palmtop computer to complete EMA recordings over the following two weeks. Attempts were made to schedule 2–3 visits with each participant during this two-week interval to obtain recorded data and address any technical problems (e.g., a broken palmtop computer) or compliance issues. Participants were given feedback at each visit regarding their compliance rates and data quality. Participants were compensated $100 per week for completing assessments, and received a $50 bonus for a compliance rate of at least 80% responding within 45 minutes to random signals.

Measures

Baseline Interviews

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorder, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P; First et al., 1995) is a semi-structured interview that was used to determine DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for AN and sub-threshold AN, as well as current and lifetime criteria for other Axis I disorders. Assessors were trained masters- or doctoral-level clinicians. SCID-I/P interviews were recorded and an independent assessor rated current eating disorder diagnoses in a random sample of 25% (n=30) of these interviews. Inter-rater reliability for current AN diagnosis (full- vs. sub-threshold) was excellent (kappa=.93).

EMA Measures

Participants were asked to report all eating episodes and to indicate whether the episode was a snack, a meal, or a binge eating episode. Participants were asked to report specific eating-related behaviors at each eating episode, including loss of control (“I felt out of control”); overeating (“I ate an amount of food that most people would consider excessive”); eating alone (“I ate by myself”); food avoidance (“I avoided certain foods”); and dietary restraint (“I attempted to eat less than others”). Participants were trained in standard definitions of eating events by clinical research staff during the EMA training session, and personally-tailored examples were provided. Participants were also instructed to report body checking behaviors during eating episode recordings (“I made sure my thighs didn’t touch” and “I checked my joints and bones for fat,” which were combined into one body checking variable for analytic purposes), and the related behavior of self-weighing during signal- and event-contingent recordings. Purging behaviors (i.e., vomiting and laxative use for weight control) were recorded at signal- and event-contingent recordings.

Momentary affect was measured using an abbreviated version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson et al., 1994). Participants rated their current mood at all event-, interval-, and signal-contingent recordings. PANAS items were chosen based on high factor loadings and previous EMA work implicating facets of negative affect that would be clinically and/or theoretically relevant (Smyth et al., 2007). Participants rated their current emotional state for each of twenty-four affect items (including a broad “negative affect” scale comprised of nervous, disgusted, distressed, ashamed, angry at self, afraid, sad, and dissatisfied with self; a “guilt” scale comprised of ashamed, angry at self, and dissatisfied with self; and a “fear” scale comprised of nervous, afraid, and shaky) on a 5-point scale, with a score of “1” corresponding to “Not at all” and a score of “5” corresponding to “Extremely” for each mood state. Alpha coefficients were .94 for negative affect, .86 for guilt, and .92 for fear in the current study.

Momentary stress was assessed during signal-contingent recordings using 23 stressful events. Fifteen stressful interpersonal events (e.g., argued with family member) were included from the Daily Stress Inventory (DSI; Brantley et al., 1989). In addition, eight stressful events relating to body image (e.g., saw reflection of self), eating (e.g., eating high risk food), and eating disorder treatment (e.g., saw therapist, dietician or doctor) were included based upon clinical relevance.

Statistical Analysis

Latent profile analysis (LPA) is an extension of latent class analysis for categorical, ordinal, or continuous “indicator” variables that classifies these variables into unobserved (i.e., latent) categorical groups based on the principle of conditional independence (i.e., within each identified class, indicator variables should be uncorrelated; Vermunt et al., 2005). Since eating behavior in AN is poorly understood, and because participants’ characterization of their eating behavior may not correspond with investigator-based definitions (e.g., Burd et al., 2009), LPA was selected based on the premise that it is an atheoretical, empirical classification approach. Five EMA-reported eating-related variables (loss of control, overeating, eating alone, food avoidance, and dietary restriction) were selected as the indicator variables of eating episodes to represent a range of pathological and non-pathological eating, and based on their relevance to eating patterns in AN (Engel et al., 2013; Fairburn, 2008). Using MPlus 7.11 (Muthén et al., 1998–2013), 1- to 10-class models were fit in the analysis, and identification of the best fitting model was based on minimization of the Consistent Akaike Information Criterion (cAIC; Bozdogan, 1987) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978). Eating episodes were nested within subject to account for repeated observations. Class membership assignments of eating episodes were based on posterior Bayesian probabilities.

Generalized estimating equations were conducted in SPSS version 21.0 to validate the eating episode classes on EMA-reported concurrent negative affect, likelihood of engaging in compensatory behaviors, likelihood of engaging in body checking, likelihood of engaging in self-weighing, and number of stressors. A chi-square test was used to compare AN restricting and AN binge/purge subtypes with respect to their likelihood of endorsing different classes of eating episodes.

RESULTS

Descriptive Characteristics

Participants provided 15,017 separate EMA recordings representing 1,767 separate participant days. These included 9,088 responses to signals, 3,445 event-contingent reports of eating episodes, 1,006 event-contingent reports of AN behaviors, and 1,478 end-of-day recordings. Compliance rates to signals averaged 87% (range=58–100%); 77% of all signals were responded to within 45 minutes. Compliance with end-of-day ratings averaged 89% (range=24–100%).

Eating Episode Identification and Description

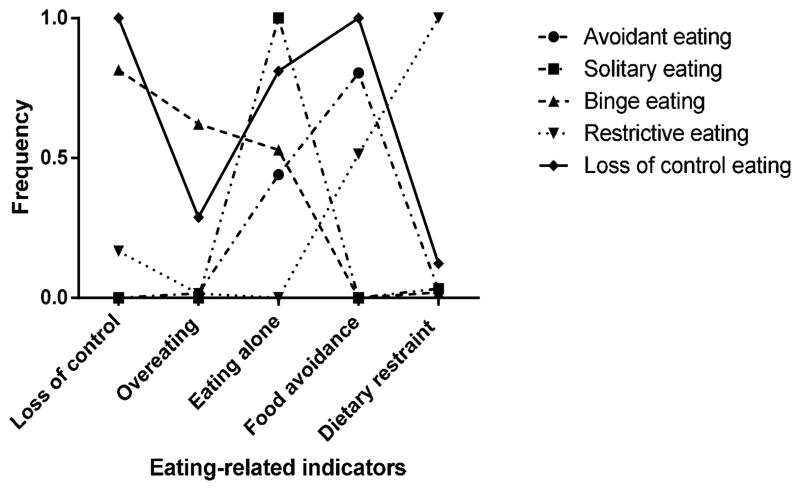

A total of 4,261 EMA-based eating episodes reported across event-, interval-, and signal-contingent recordings were included in the LPA. LPA results supported a 5-class solution (see Table 1). The classes were examined and the following labels were applied to different classes: 1) avoidant eating (n=1,419; 33.3%); 2) solitary eating (n=1,371; 32.2%); 3) binge eating (n=670; 15.7%); 4) restrictive eating (n=516; 12.1%); and 5) loss of control eating (n=285; 6.7%). As can be seen in Figure 1, avoidant eating was characterized by high levels of food avoidance; modest levels of eating alone; and low levels of loss of control, overeating, and dietary restraint. Solitary eating was characterized by high levels of eating alone, and low levels of loss of control, overeating, food avoidance, and dietary restraint. Binge eating was characterized by high levels of loss of control, overeating, and eating alone; and low levels of food avoidance and dietary restraint. Restrictive eating was characterized by low levels of loss of control, eating alone, and overeating; modest levels of food avoidance; and high levels of dietary restraint. Finally, loss of control eating was characterized by high levels of loss of control, eating alone, and food avoidance; modest levels of overeating; and low levels of dietary restriction.

Table 1.

Fit indices for 1- to 10-class latent profile analysis models

| Number of classes | N | Parameters | Entropy | LL | BIC | cAIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4261 | 5 | --- | −11362.8 | 22767.41 | 22772.41 |

| 2 | 4261 | 11 | 1 | −10934.3 | 21960.57 | 21971.57 |

| 3 | 4261 | 17 | 0.756 | −10529.2 | 21200.46 | 21217.46 |

| 4 | 4261 | 23 | 0.805 | −10478.7 | 21149.59 | 21172.59 |

| 5 | 4261 | 29 | 0.776 | −10446.5 | 21135.33 | 21164.33 |

| 6 | 4261 | 35 | 0.857 | −10430.1 | 21152.72 | 21187.72 |

| 7 | 4261 | 41 | 0.771 | −10423.9 | 21190.54 | 21231.54 |

| 8 | 4261 | 47 | 0.87 | −10423.7 | 21240.16 | 21287.16 |

| 9 | 4261 | 53 | 0.76 | −10423.7 | 21290.3 | 21343.3 |

| 10 | 4261 | 59 | 0.772 | −10423.7 | 21340.44 | 21399.44 |

Figure 1.

Relative frequency of latent profile analysis eating-related indicators among eating episode classes

Eating Episode Validation

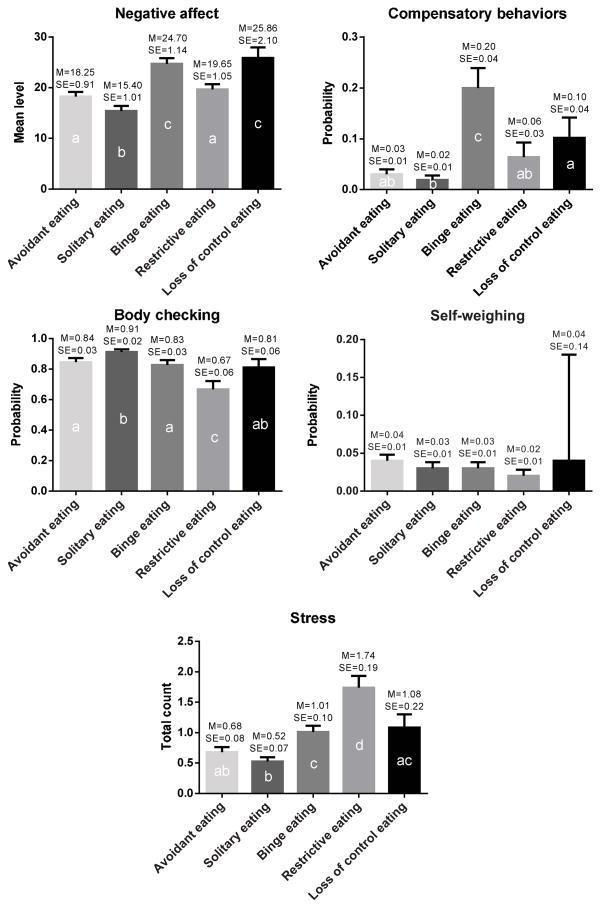

Overall, comparisons of eating episode classes on concurrent EMA measures suggest that the eating episode classes identified through LPA were associated with distinct contemporaneous affective, behavioral, and environmental features (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Eating episode class differences with respect to concurrently reported affective, behavioral, and environmental features

Note: Differing letters indicate significant differences

Negative Affect

Loss of control and binge eating were associated with the highest levels of concurrent negative affect, and solitary eating with the lowest; restrictive and avoidant eating were associated with equivalent levels of concurrent negative affect that were significantly higher than those associated with solitary eating, and significantly lower than those associated with loss of control and binge eating (Wald chi-square=88.47; p<.001; pseudo R2=0.75). A similar pattern of findings was observed for the guilt and fear subscales (ps<.001).

Compensatory Behavior

Binge eating was associated with the greatest probability of engaging in compensatory behaviors, and solitary eating with the lowest; restrictive and avoidant eating did not differ from one another, or from loss of control eating or solitary eating in terms of likelihood of engaging in compensatory behaviors (Wald chi-square=87.45; p<.001; pseudo R2=0.63).

Body Checking and Self-Weighing

Restrictive eating was associated with the lowest probability of engaging in body checking and solitary eating with the highest; loss of control eating, binge eating, and avoidant eating were associated with equivalent probabilities of engaging in body checking behaviors. (Wald chi-square=29.00; p<.001; pseudo R2=0.66). There were no differences among the eating episode classes in terms of probability of engaging in self-weighing (Wald chi-square=4.17; p=.38).

Stress Ratings

Restrictive eating was associated with the highest overall number of concurrently-reported stressors; loss of control and binge eating were associated with similar numbers of stressors, as were avoidant and solitary eating (Wald chi-square=65.86; p<.001; pseudo R2=0.71). Loss of control eating and avoidant eating did not differ in terms of the number of concurrently reported stressors.

Diagnostic Subtype

Participants meeting criteria for AN binge/purge subtype reported a disproportionately higher number of loss of control and binge eating episodes relative to those meeting criteria for the restricting subtype, who reported a disproportionately higher number of solitary eating episodes [χ2(N=4,261)=238.61; p<.001].

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the current study was to determine if distinct classes of eating behaviors could be identified in women with AN based on the presence or absence of multiple eating-related indicators. We identified five classes of eating episodes, characterized to varying degrees by loss of control, overeating, eating alone, food avoidance, and dietary restraint. These eating episode classes differed across measures of concurrent affect, compensatory behaviors, body checking, and stressful events, but not self-weighing, perhaps suggesting that this latter activity does not have a distinct functional purpose in the context of overt eating behaviors. Overall, results help clarify the nature of eating patterns in AN and can be used to inform the development or refinement of maintenance models for AN, as well as clinical interventions for the disorder, which may benefit from addressing functional aspects of eating behavior.

According to our findings, solitary eating may approximate “typical” eating in the AN population, as it was associated with the lowest levels of negative affect and the lowest probability of concurrent compensatory behaviors and stressors. This type of eating episode could reflect the nature of the current sample, which was comprised primarily of single, young adult women, who may tend to live alone and/or eat while engaged in other activities such as working or studying. Although solitary eating episodes were characterized by low levels of other pathological eating behaviors (e.g., dietary restriction, loss of control while eating), they were accompanied by the highest likelihood of engaging in body checking, perhaps because these behaviors may tend to occur secretively. It is unclear from the current data if eating alone is detrimental (e.g., reflecting the relative social isolation of the AN population; Arcelus et al., 2013) or helpful (i.e., in terms of improving food intake or nutrition); this question should be explored in future studies.

Contrary to expectation, restrictive eating was the class least likely to co-occur with body checking, perhaps reflecting that restriction itself provides a means of self-soothing or distraction which may otherwise be sought through checking behaviors. Interestingly, restrictive eating was also associated with modest levels of negative affect but the highest likelihood of experiencing a concurrent stressor. These results suggest that negative affect and stressful events may be experienced differently by women with AN. Loss of appetite is a normative reaction to the experience of certain types of stressors (Adam et al., 2007). However, it can be inferred from our data that this “normative” process reflects an exaggerated and ultimately harmful attempt to cope with stressors in AN, as characterized by intentional efforts to restrain one’s eating and avoid certain foods, behaviors that presumably maintain the disorder. It could be that restrictive eating is effective at minimizing the immediate effect of stressors, but less so at alleviating consequent negative affect, which may be more strongly influenced by the alternative maladaptive behavior of binge eating, perhaps due to variations in neural activation patterns associated with these different constructs (Diekhof et al., 2011). It is also plausible that restrictive eating itself intensifies one’s experience of negative affect and stress, thus highlighting the need for longitudinal data to further examine the nature of the relations among behaviors, affect, and events in AN.

Overall, loss of control and binge eating, both characterized by loss of control, were associated with the highest levels of negative affect and the greatest likelihood of engaging in compensatory behaviors. Although affect regulation models of binge eating have tended to focus on the reinforcing or emotion-regulating properties of binge eating in bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED; Haedt-Matt et al., 2011), these results (although correlational) suggest that binge eating behaviors may serve a similar function in AN. In particular, the combination of elevated negative affect and greater likelihood of purging may fit especially well with the “trade-off” model of binge eating, which presupposes that negative emotions prior to binge eating (e.g., loneliness) are replaced by less aversive emotions thereafter (e.g., guilt; Kenardy et al., 1996). Furthermore, compensatory behaviors (e.g., purging) may be a means of alleviating these post-binge emotions. Because our data examined concurrent eating behavior, negative affect, and compensatory behaviors, it cannot be deduced that negative affect prompted the occurrence of these behaviors (however, previous EMA work by our group has demonstrated that negative affect increases prior to binge eating and purging, and decreases thereafter; Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007). In order to further test the trade-off model, future research should seek to more specifically determine how levels and specific types of negative mood states vary in the time period between the occurrence of these two behaviors.

In terms of clinical implications, our results suggest that interventions for AN should target multiple aspects of eating behavior, including both under- and over-eating, as different eating patterns are associated with distinct clinical features. Treatments should further address negative affect, which may co-occur with binge eating, as well as stress, which may co-occur with restrictive eating, although additional research is needed to disentangle the temporal order of these constructs. Finally, body checking should be further investigated with respect to eating behavior in order to inform intervention research, as it may serve to reinforce problematic eating (e.g., checking one’s body to ensure that restrictive eating was successful, or to bolster dieting efforts after a binge eating episode), or, alternatively, serve as a trigger for eating disorder behaviors.

Study strengths include the large sample size for a study of AN, and the use of momentary, ecologically valid data collected via EMA to characterize and validate eating episodes. Nevertheless, there were several limitations warranting discussion. First, although participants were thoroughly instructed in how to report their eating episodes via EMA, the indicators used to classify eating episodes were mostly based on subjective data (e.g., perception of eating an excessive amount of food). Future studies should examine whether more objective measures of eating behavior (e.g., dietary composition) correspond to the eating episodes identified in this study. Relatedly, the EMA item assessing dietary restraint alludes to the presence of others (“I attempted to eat less than others”), thus distinctions between the restrictive eating class (which was characterized by high levels of dietary restraint) and the solitary eating class (which was characterized by low levels of dietary restraint) may be due in part to this methodology; however, clear differences between the two classes across validators (particularly body checking and stress) somewhat allay this concern. Second, the eating-related indicators included in the LPA were not exhaustive, and there may be additional eating episode classes that were not captured by the current data. Similarly, only self-induced vomiting and laxative misuse were assessed via EMA due to the low base rates of other compensatory behaviors, thus future studies should include a more comprehensive assessment of eating disorder behaviors. Third, in order to incorporate every available data-point into the analyses, we could not apply longitudinal analyses that examine temporally sensitive cause-effect relationships and instead examined eating-, mood-, and stress-related variables that were measured concurrently. This procedure limits our ability to infer temporal relationships among the constructs from the present findings; future studies should thus examine how relations among the various constructs unfold in time. Fourth, the largely Caucasian and exclusively female sample may limit generalizability of our findings. Finally, not all validators were assessed at every EMA recording (e.g., stressful events were only assessed at signal-contingent recordings), which could have impacted our results.

In summary, our findings highlight the variability of eating episodes in AN, and their distinctiveness in terms of clinical correlates. Future research should clarify the role and functions of these eating episode classes in AN in order to most effectively improve treatments targeting behavioral symptoms and psychosocial functioning in individuals with the disorder.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology and Behavior. 2007;91:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arcelus J, Haslam M, Farrow C, Meyer C. The role of interpersonal functioning in the maintenance of eating psychopathology: A systematic review and testable model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52:345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Brantley P, Jones G. Daily Stress Inventory: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Burd C, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Lystad C, Le Grange D, Peterson CB, Crow S. An assessment of daily food intake in participants with anorexia nervosa in the natural environment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:371–374. doi: 10.1002/eat.20628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekhof EK, Geier K, Falkai P, Gruber O. Fear is only as deep as the mind allows: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on the regulation of negative affect. Neuroimage. 2011;58:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Le Grange D, Simonich HK, Cao L, Lavender JM, Gordon KH. The role of affect in the maintenance of anorexia nervosa: Evidence from a naturalistic assessment of momentary behaviors and emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:709–719. doi: 10.1037/a0034010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Wright TL, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Venegoni EE. A study of patients with anorexia nervosa using ecologic momentary assessment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:335–339. doi: 10.1002/eat.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeset EM, Gulliksen KS, Nordbo RH, Skarderud F, Holte A. The link between negative emotions and eating disorder behaviour in patients with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. 2012;20:451–460. doi: 10.1002/erv.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrom MH, Weltzin TE, Neuberger S, Srinivasagam N, Kaye WH. Twenty-four-hour food intake in patients with anorexia nervosa and in healthy control subjects. Biological Psychiatry. 1994;36:696–702. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J, editors. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders: Patient edition, SCIDI/P. New York, NY: Biometrics; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gwirtsman HE, Kaye WH, Curtis SR, Lyter LM. Energy intake and dietary macronutrient content in women with anorexia nervosa and volunteers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1989;89:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadigan CM, Anderson EJ, Miller KK, Hubbard JL, Herzog DB, Klibanski A, Grinspoon SK. Assessment of macronutrient and micronutrient intake in women with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28:284–292. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<284::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:660–681. doi: 10.1037/a0023660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrook D, Oldershaw A, Rimes K, Schmidt U, Tchanturia K, Treasure J, Richards S, Chalder T. Emotional expression, self-silencing, and distress tolerance in anorexia nervosa and chronic fatigue syndrome. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;50:310–325. doi: 10.1348/014466510X519215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J. Emotion recognition and regulation in anorexia nervosa. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2009;16:348–356. doi: 10.1002/cpp.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenardy J, Arnow B, Agras WS. The aversiveness of specific emotional states associated with binge-eating in obese subjects. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;30:839–844. doi: 10.3109/00048679609065053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, De Young KP, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Le Grange D. Daily patterns of anxiety in anorexia nervosa: Associations with eating disorder behaviors in the natural environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013a;122:672–683. doi: 10.1037/a0031823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Crow S, Peterson CB, Le Grange D. A naturalistic examination of body checking and dietary restriction in women with anorexia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013b;51:507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer LE, Schebendach J, Bodell LP, Shingleton RM, Walsh BT. Eating behavior in anorexia nervosa: before and after treatment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:290–293. doi: 10.1002/eat.20924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy C, Mitchell JE. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD, editors. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Racine SE, Wildes JE. Emotion dysregulation and symptoms of anorexia nervosa: The unique roles of lack of emotional awareness and impulse control difficulties when upset. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1002/eat.22145. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistic. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass JE, Sysko R, Mayer L, Berner LA, Schebendach J, Wang Y, Chen H, Albano AM, Simpson HB, Walsh BT. Pre-meal anxiety and food intake in anorexia nervosa. Appetite. 2010;55:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Walsh BT, Schebendach J, Wilson GT. Eating behavior among women with anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82:296–301. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidsun J. User’s guide. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations, Inc; 2005. Latent GOLD 4.0. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BT. The enigmatic persistence of anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:477–484. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12081074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form. Iowa City: The University of Iowa; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types, and uses. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Wildes JE, Marcus MD, Bright AC, Dapelo MM, Psychol MC. Emotion and eating disorder symptoms in patients with anorexia nervosa: An experimental study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:876–882. doi: 10.1002/eat.22020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildes JE, Ringham RM, Marcus MD. Emotion avoidance in patients with anorexia nervosa: Initial test of a functional model. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:398–404. doi: 10.1002/eat.20730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]