Abstract

Thirteen novel non-canonical amino acids were synthesized and tested for suppression of an amber codon using a mutant pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase– pair. Suppression was observed with varied efficiencies. One non-canonical amino acid in particular contains an azide that can be applied for site-selective protein labeling.

Site-selective installation of non-canonical amino acids (NCAAs) at an amber codon is an efficient approach to synthesize proteins with unique functionalities; applications span from basic studies such as protein cellular localization and protein–protein interaction analysis, to biotechnological applications such as the synthesis of heat stable enzymes and therapeutic protein manufacturing.1–5 Two aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase–tRNACUA pairs have been well adapted for the genetic incorporation of NCAAs at amber codons in bacteria. One is the tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase– pair that was derived from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii.6–8 The other is the pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase (PylRS)– pair that naturally occurs in some methanogenic archaea.9–12 Due to its broad-spectrum orthogonality from bacteria to human cells and the fact that it can be easily engineered to target a large variety of NCAAs, including natural amino acids with posttranslational modifications, the PylRS– pair has captivated researchers for the past several years.13–28 One of our major contributions to the NCAA research field has been the development of PylRS mutants capable of incorporating a number of phenylalanine derivatives, which are substantially different from the structure of pyrrolysine, the native substrate of PylRS.29–31 More specifically, we have recently shown that a rationally designed, N346A/C348A mutant of PylRS (PylRS(N346A/C348A)) is capable of incorporating seven para- and twelve meta-substituted phenylalanine derivatives at amber codons in coordination with .30,31 This broad substrate scope obviates the need to undergo the arduous task of discovering a new mutant for each NCAA. Herein we demonstrate that PylRS(N346A/C348A) has an even broader substrate scope than previously reported.

Our previous studies revealed a large active site pocket in PylRS(N346A/C348A).30 Removal of the N346 side chain amide dismisses the steric clash that prevents the binding of the aromatic side chain of phenylalanine and the loss of the C348 thiol yields a cavernous pocket capable of binding the para- or meta-substituted phenylalanine described above. Interestingly, although phenylalanine derivatives with small para-substituents have shown to be ineffective substrates for PylRS(N346A/C348A), their isomers with meta-substituents act as highly efficient substrates of PylRS(N346A/C348A) for their genetic incorporation at amber codons.30,31 In other words, phenylalanine derivatives with para-substituents can only be incorporated when they possess large side chains. Upon further inspection, it appears that a majority of the vacancy in the active site pocket of PylRS(N346A/C348A) exists near the meta position of phenylalanine. Encouraged by our preliminary work, we reasoned that PylRS(N346A/C348A) could incorporate phenylalanine derivatives with more sterically demanding side chains.

Our investigation began with the synthesis and genetic incorporation of four different para-substituted phenylalanine derivatives (1–4 in Fig. 1A), each with a unique functionality and steric requirement. Synthesis of these derivatives followed the same strategy presented in one of our previous reports of the N346A/C348A mutant,30 with the exception of NCAA 1, which was synthesized using a different approach (see the ESI†). These four NCAAs were then tested for their tolerability by PylRS(N346A/C348A). An E. coli BL21(DE3) cell that harbours two plasmids, pEVOL-pylT-PylRSN346A/C348A and pET-pylT-sfGFP2TAG, was employed for the investigation. pEVOL-pylT-PylRSN346A/C348A contains genes coding PylRS(N346A/C348A) and ; pET-pylT-sfGFP2TAG carries a coding gene and a non-sequence-optimized superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) gene with an amber mutation in position S2 (sfGFP2TAG). The same cells were used in the initial test of the recognition of para-substituted phenylalanine derivatives by PylRS(N346A/C348A).30 Growth in minimal media supplemented with 1 mM IPTG and 0.2% arabinose without NCAA afforded a minimal expression level of full-length sfGFP (<0.3 mg L−1). Addition of any of 1–4 at 2 mM to the medium all promoted full-length sfGFP expression (Fig. 1A). The expression levels for 1–3 are comparable to that for para-propargyloxy-phenylalanine (7.8 mg L−1),30 and the electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis of four purified sfGFP variants displayed molecular weights that agreed well with the theoretical values corresponding to full-length proteins with the first methionine (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Structures of 1–4 and their site-specific incorporation into sfGFP at its S2 position. (B) Deconvoluted ESI-MS spectra of sfGFP variants incorporated with 1–4. Their theoretical values are 27 832 Da for 1, 27873 Da for 2, 27886 Da for 3, and 27856 Da for 4. Satellite signals are largely due to metal ion adducts (i.e. Li, Na, K).

The results obtained for 1–4 demonstrate that PylRS(N346A/C348A) tolerates phenylalanine derivative substrates with rigid and bulky substituents at the para position. However, ESI-MS data for compound 3 also show a small side peak corresponding to the incorporation of phenylalanine, a result we have observed previously. The remaining satellite peaks for these compounds correspond to common metal adducts in ESI-MS. Additionally, results obtained for 1 demonstrated that both meta and para positions can be occupied without detriment to expression levels. These results, coupled with our previous endeavours, led us to wonder if phenylalanine derivatives with long-chain meta-substituents could serve as substrates of PylRS(N346A/C348A) for genetic incorporation as well. To investigate this hypothesis, a series of meta-alkoxy and meta-acyl phenylalanines with substituent chain lengths of up to six carbons were synthesized. We chose these specific derivatives because the parent NCAAs meta-methoxy-phenylalanine and meta-acety-lphenylalanine act as efficient substrates for PylRS(N346A/C348A). The synthesis of meta-alkoxy-phenylalanines was straightforward, starting with a published route to obtain protected meta-tyrosine, at which point the intermediate was subjected to various alkyl halides to afford different derivatives. Acidic deprotection then yielded free amino acids as racemic chloride salts. The synthesis of meta-acyl-phenylalanines was more divergent. Alkyl Grignards were added to a solution of meta-tolunitrile, which afforded acylbenzenes upon acidic workup. Radical bromination and then displacement with diethylacetamidomalonate afforded protected meta-acyl-phenylalanines that were deprotected in 6 M HCl to obtain free amino acids. More detailed synthetic routes can be found in the ESI.†

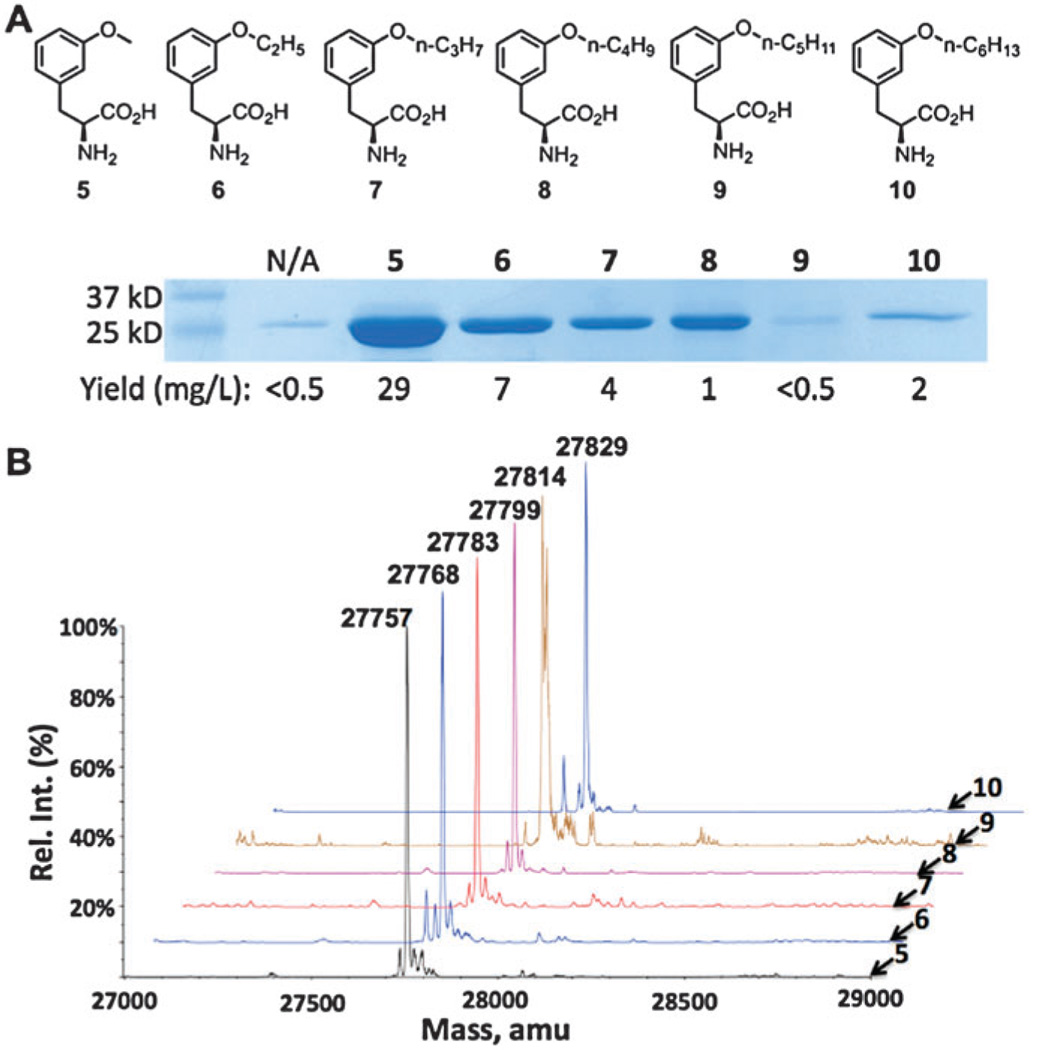

With the desired NCAAs in hand, we thenceforth tested their incorporation efficacies at amber codons using the PylRS(N346A/C48A)– pair. The E. coli cells used for these compounds harboured two plasmids, pEVOL-pylT-PylRSN346A/C348A and pET-pylT-sfGFPS2TAG′. pET-pylT-sfGFPS2TAG′ contains a sequence-optimized sfGFP with an amber mutation at its S2 position (sfGFPS2TAG′). In comparison to the sfGFP2TAG gene in pET-pylT-sfGFP2TAG, sfGFPS2TAG′ has one more alanine residue in front of the amber mutation. Growing this cell in minimal media without NCAA yielded a minimal expression level of full-length sfGFP. However, all ether NCAAs 6–10 (2 mM) in the medium promoted the synthesis of sfGFP with a designated NCAA incorporated (Fig. 2A). In comparison to phenylalanine derivatives with small meta-substituents such as 5, 6–10 apparently have low incorporation levels. Molecular weights of purified sfGFP variants determined by ESI-MS agreed well with the theoretical values corresponding to a designated NCAA at the S2 position and the first methionine hydrolysed (Fig. 2B). The removal of the first methionine is due to the insertion of alanine after it. A number of smaller signals can be observed, but they largely correspond to common metal adducts; the expected masses were always the major signal. Compounds 8, 9, and 10 have low solubility; when added to the medium at 2 mM, compound 10 was observed to precipitate after 12 h of expression. The low sfGFP expression levels for 8, 9 and 10 may be partially due to the toxicity of the compounds; indeed, smaller pellet sizes are observed for 8 and 9. Although the sfGFP expression level for 9 was very low, the purified sfGFP displayed an ESI-MS molecular weight that still matched the theoretical value of sfGFP with 9 incorporated at S2, indicating that a low concentration of 9 was still sufficient to observe incorporation of 9 at the amber mutation site.

Fig. 2.

(A) Structures of 5–10 and their site-specific incorporation into sfGFP at its S2 position. (B) Deconvoluted ESI-MS spectra of sfGFP variants incorporated with 5–10. Their theoretical values are 27758 Da for 5, 27772 Da for 6, 27 786 Da for 7, 27800 Da for 8, 27814 Da for 9, and 27828 Da for 10.

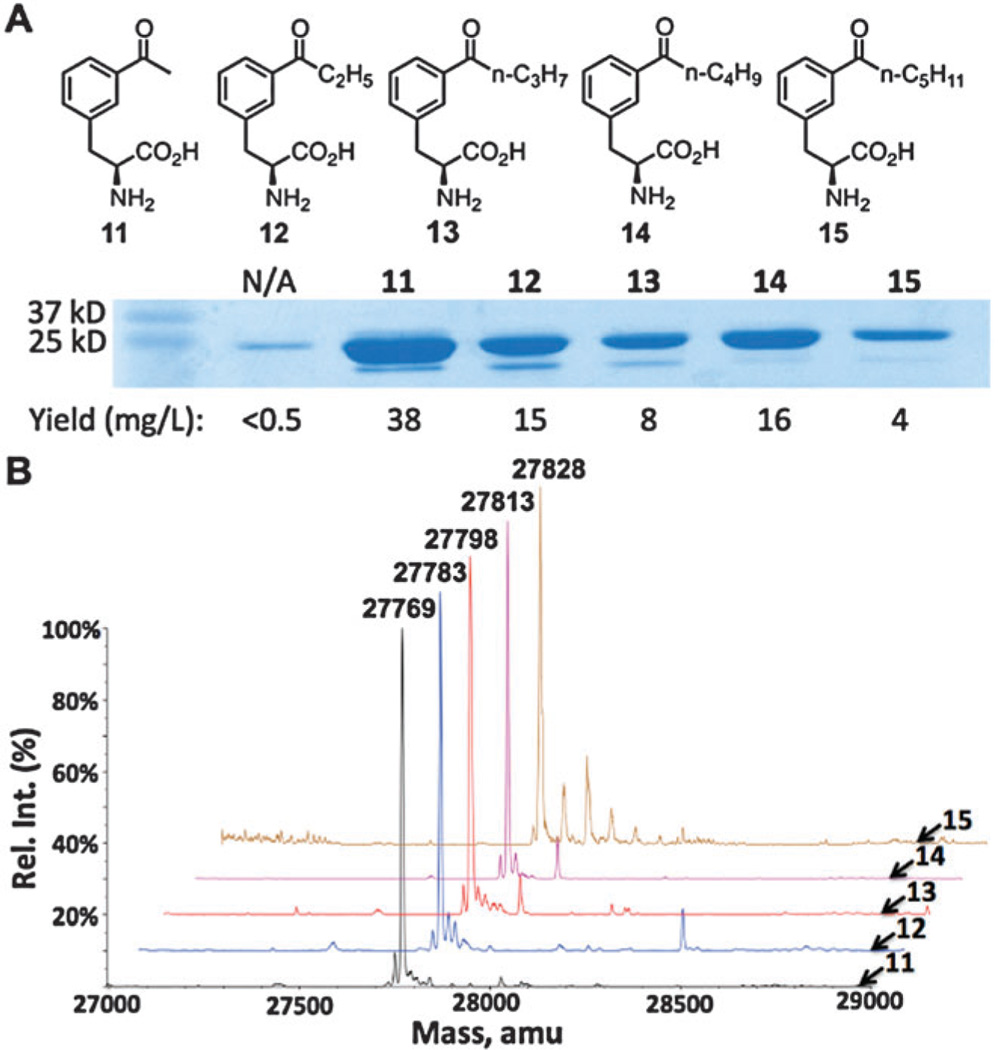

Overall, addition of ketone derivatives 12–15 at 2 mM to the medium promoted high sfGFP expression yields, and longer alkyl lengths had less of an impact on protein yields in comparison to the ether series 6–10, though the sfGFP expression levels for 12–15 are lower than that for 11 (Fig. 3A). This series of NCAAs are also readily soluble, with no precipitation observed in the medium after overnight incubation. ESI-MS analysis of the purified sfGFP variants confirmed high incorporation fidelities of 12–15 at the S2 site.

Fig. 3.

(A) Structures of 11–15 and their site-specific incorporation into sfGFP at its S2 position. (B) Deconvoluted ESI-MS spectra of sfGFP variants incorporated with 11–15. Their theoretical values are 27 770 Da for 11, 27 784 Da for 12, 27 798 Da for 13, 27 812 Da for 14, and 27 826 Da for 15. Compounds 13 and 14 show small signals corresponding to an N-terminal methionine on sfGFP. Compound 15 has several small signals attributed to sodium and potassium adducts.

Among all of the novel NCAAs that can be taken by PylRS(N346A/C348A), 2 has an active azide functionality for a click reaction with an alkyne32 and 12–15 contain a ketone group that potentially reacts with a hydroxylamine. Both functionalities can be applied for site-selective labeling of proteins incorporated with 2 and 12–15. Since labeling of sfGFP incorporated with 11 with a hydroxylamine dye was demonstrated previously,31 we chose to demonstrate the selective labeling of 2 using a diarylcyclooctyne dye D1 in this study (Fig. 4). D1 contains a strained alkyne that undergoes a spontaneous reaction with an azide.33 Incubating sfGFP incorporated with 2 with D1 overnight led to an intensely fluorescently labeled protein; however, the same reaction with sfGFP incorporated with 3 did not yield any fluorescently labeled final product. This result indicates that genetically incorporated 2 can be applied to site-specifically introduce biophysical and biochemical probes to proteins for a large variety of studies.

Fig. 4.

Labeling of sfGFP incorporated with 2 (sfGFP-2) and sfGFP incorporated with 3 (sfGFP-3) with dye D1. The top panel shows the Coomassie blue stained SDS-PAGE gel and the bottom panel shows the fluorescent image of the same gel under UV irradiation before the gel was stained with Coomassie blue.

In summary, we have shown that thirteen novel NCAAs were genetically incorporated into protein at the amber codon in E. coli using the PylRS(N346A/C348A)– pair. This result, coupled with our previous findings, shows a surprisingly broad substrate scope for PylRS(N346A/C348A). Investigations are underway to determine aspects of the active site pocket of PylRS(N346A/C348A) that lead to this broad substrate spectrum. The current study has great implications in understanding amino acid structure tolerance of the protein translation system. The expanded genetically encoded NCAA pool can also be applied to generate phage and E. coli displayed peptide libraries with expanded chemical moieties for drug discovery, a direction we are actively pursuing at the current stage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Welch Foundation (grant A-1715), the National Science Foundation (grant CHEM-1148684), and the National Institute of Health (grant 1R01CA161158).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Synthesis, protein expression, protein labeling, and mass spectrometry analysis. See DOI: 10.1039/c3cc49068h

Notes and references

- 1.Liu WR, Wang YS, Wan W. Mol. Biosyst. 2011;7:38–47. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00216j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gautier A, Deiters A, Chin JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2124–2127. doi: 10.1021/ja1109979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang M, Lin S, Song X, Liu J, Fu Y, Ge X, Fu X, Chang Z, Chen PR. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:671–677. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Y, Ghirlanda G, Vaidehi N, Kua J, Mainz DT, Goddard IW, DeGrado WF, Tirrell DA. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2790–2796. doi: 10.1021/bi0022588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu CC, Schultz PG. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz PG. Science. 2001;292:498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie J, Schultz PG. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:775–782. doi: 10.1038/nrm2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin JW, Santoro SW, Martin AB, King DS, Wang L, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9026–9027. doi: 10.1021/ja027007w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasan G, James CM, Krzycki JA. Science. 2002;296:1459–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1069588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blight SK, Larue RC, Mahapatra A, Longstaff DG, Chang E, Zhao G, Kang PT, Green-Church KB, Chan MK, Krzycki JA. Nature. 2004;431:333–335. doi: 10.1038/nature02895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann H, Peak-Chew SY, Chin JW. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:232–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan W, Huang Y, Wang Z, Russell WK, Pai PJ, Russell DH, Liu WR. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:3211–3214. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greiss S, Chin JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14196–14199. doi: 10.1021/ja2054034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancock SM, Uprety R, Deiters A, Chin JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14819–14824. doi: 10.1021/ja104609m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukai T, Kobayashi T, Hino N, Yanagisawa T, Sakamoto K, Yokoyama S. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;371:818–822. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanagisawa T, Ishii R, Fukunaga R, Kobayashi T, Sakamoto K, Yokoyama S. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parrish AR, She X, Xiang Z, Coin I, Shen Z, Briggs SP, Dillin A, Wang L. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:1292–1302. doi: 10.1021/cb200542j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen PR, Groff D, Guo J, Ou W, Cellitti S, Geierstanger BH, Schultz PG. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:4052–4055. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou CJ, Uprety R, Davis L, Chin JW, Deiters A. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:480–483. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang YS, Wu B, Wang Z, Huang Y, Wan W, Russell WK, Pai PJ, Moe YN, Russell DH, Liu WR. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6:1557–1560. doi: 10.1039/c002155e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee YJ, Wu B, Raymond JE, Zeng Y, Fang X, Wooley KL, Liu WR. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:1664–1670. doi: 10.1021/cb400267m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fekner T, Li X, Lee MM, Chan MK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:1633–1635. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Fekner T, Ottesen JJ, Chan MK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:9184–9187. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umehara T, Kim J, Lee S, Guo LT, Soll D, Park HS. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:729–733. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polycarpo CR, Herring S, Berube A, Wood JL, Soll D, Ambrogelly A. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6695–6700. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plass T, Milles S, Koehler C, Schultz C, Lemke EA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:3878–3881. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plass T, Milles S, Koehler C, Szymanski J, Mueller R, Wiessler M, Schultz C, Lemke EA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:4166–4170. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen DP, Lusic H, Neumann H, Kapadnis PB, Deiters A, Chin JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8720–8721. doi: 10.1021/ja900553w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang YS, Russell WK, Wang Z, Wan W, Dodd LE, Pai PJ, Russell DH, Liu WR. Mol. Biosyst. 2011;7:714–717. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00217h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang YS, Fang X, Wallace AL, Wu B, Liu WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2950–2953. doi: 10.1021/ja211972x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang YS, Fang X, Chen HY, Wu B, Wang ZU, Hilty C, Liu WR. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:405–415. doi: 10.1021/cb300512r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jewett JC, Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3688–3690. doi: 10.1021/ja100014q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.