Abstract

Background

Recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) is approved for treatment of bleeding in hemophilia patients with inhibitors but has been applied to a wide range of off-label indications.

Objective

To estimate patterns of off-label rFVIIa use in United States hospitals.

Design

Retrospective database analysis.

Setting

Data were extracted from the Premier Perspectives database (Premier, Inc.; Charlotte, NC), which contains discharge records from a sample of academic and non-academic U.S. hospitals.

Patients

12,644 hospital discharge records for patients who received rFVIIa during a hospitalization.

Measurements

Hospital diagnoses and patient dispositions from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2008. Statistical weights for each hospital were used to provide national estimates of rFVIIa use.

Results

Between 2000 and 2008, off-label use of rFVIIa in hospitals increased more than 140-fold, such that in 2008, 97% (95% CI, 96% to 98%) of 18311 in-hospital uses were off-label. In contrast, in-hospital use for hemophilia increased less than 4-fold and accounted for 3% (95% CI, 1.9% to 3.5%) of use in 2008. Cardiovascular surgery (29%; 95% CI, 21% to 33%) and trauma (29%; 95% CI, 19% to 38%) and intracranial hemorrhage (11%; 95%CI, 7.7% to 14%) were the most common indications for rFVIIa use. Across all indications, in-hospital mortality was 27% (95% CI, 19% to 34%), and 43% (95% CI, 35% to 50%) of patients were discharged to home.

Limitations

Accuracy and completeness of the discharge diagnoses and patient medication records in the database sample cannot be verified.

Conclusion

Off-label use of rFVIIa in the hospital setting far exceeds use for approved indications. These patterns raise concern about the application of rFVIIa to conditions that lack strong supporting evidence.

Primary Funding Source

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

To be approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), medications must clear significant regulatory hurdles and demonstrate both efficacy and a lack of excessive harms in clinical trials. After a medication has received approval, there are no further limitations on its use, either on- or off-label. In many cases, this leads to medications being approved for narrowly defined indications, followed by substantial use in areas that have not been well-studied (1).

Recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa; Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) was approved by the FDA in 1999 for treatment of spontaneous or surgical bleeding episodes in patients with hemophilia A or B who have inhibitors to factor VIII or factor IX. When first introduced, rFVIIa was used predominantly for these indications. After it became widely available, however, rFVIIa was rapidly employed in the treatment or prophylaxis of bleeding in other conditions. Although rFVIIa activity is thought to be confined to sites of endothelial injury (2–3), the potential for thromboembolic complications with its use has been demonstrated in several trials and retrospective analyses (4–9), raising concern about potential harms with widespread off-label application. To estimate patterns of off-label, in-hospital rFVIIa use, we performed a retrospective evaluation of data from the Premier Perspectives database of U.S. hospitals. This representative sample was used to project national usage patterns from January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2008.

Methods

Design Overview

We purchased access to data from the Premier Perspectives database from Premier, Inc. (Charlotte, NC). The dataset encompassed all hospitalizations during which rFVIIa was ordered for a patient for the period January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2008. We analyzed this dataset to categorize the discharge diagnoses and patient outcome for each rFVIIa-associated hospitalization.

Hospital Sample

The Premier Perspectives database contains data from 615 non-federal U.S. hospitals. Institutional participation in the database is voluntary. Data included are patient demographics, primary and secondary diagnoses (coded by International Classification of Diseases, Revision 9; ICD-9), length of stay, medications used, and disposition for each hospitalization. We identified 12,644 hospitalization in which rFVIIa was administered to patients during 2000–2008. A total of 286,100 diagnosis and procedure ICD-9 codes were reported for this cohort.

Categorizations of Use

We constructed a descending hierarchy of ICD-9 codes to categorize each case into mutually exclusive indication categories (Appendix Table 1). This hierarchy started with the most relevant, most reliable, and most specific clinical diagnoses, followed successively by less relevant, less reliable, or less specific diagnoses. A case was assigned to a diagnostic category based on the ICD-9 code that placed it in the highest category within the hierarchy.

Appendix Table 1.

Diagnostic Hierarchy for Analysis of the Premier Perspectives Database.

| Rank in Hierarchy |

Description | Most Frequent Conditions or Procedures |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hemophilia A and B | Hemophilia A, Hemophilia B |

| 2 | Primary clotting disorders | Other clotting factor deficiencies, Glanzmann’s |

| 3 | Brain trauma | Subdural hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| 4 | Body trauma | Motor vehicle accident, fall, assault |

| 5 | Intracranial hemorrhage | Intracerebral hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage |

| 6 | Neurosurgery | Excision of lesion, craniotomy |

| 7 | Pediatric cardiac surgery | Transposition of the great vessels, ASD |

| 8 | Adult cardiac surgery | Aortic valve replacement, CABG, mitral valve |

| 9 | Obstetrical hemorrhage | Immediate post-partum hemorrhage, pre-eclampsia |

| 10 | Neonatal indications | Respiratory distress syndrome |

| 11 | Aortic aneurysm | Abdominal aortic aneurysm, thoracic aortic aneurysm |

| 12 | Prostatectomy | Retropubic prostatectomy |

| 13 | Other vascular procedures | Vascular bypass, intrabdominal venous shunt |

| 14 | Liver transplantation | Liver transplantation |

| 15 | Liver biopsy | Closed biopsy of liver, open biopsy of liver |

| 16 | Variceal bleeding | Esophageal varices |

| 17 | Other liver disease | Non-alcoholic cirrhosis, alcoholic cirrhosis |

| 18 | Non-variceal gastrointestinal bleed | Unspecified GI bleed, ischemic bowel |

| 19 | Secondary clotting disorders | Unspecified coagulation defect, defibrination syndrome |

| 20 | Pulmonary hemorrhage | Closed bronchial biopsy, hemoptysis |

| 21 | Cancer/stem cell transplant | Acute lymphoid leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia |

| 22 | Other surgical procedures | Various |

| 23 | Other diagnoses | Various |

The higher order diagnoses in this hierarchy were the FDA-approved indications of hemophilia A and B, followed by unapproved indications similar to hemophilia or approved in other nations (e.g., Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia). If these diagnoses were noted, the hospitalization was classified into that category regardless of whether other potential indications were also noted. All remaining hospitalizations were then categorized successively for an array of off-label indications (Appendix Table 1). Sensitivity analyses of this coding hierarchy had little effect on the main findings. The greatest change in the distribution between indications was seen when trauma was moved lower in the hierarchy, which suggests that trauma frequently occurs in the setting of other disease processes. We chose to prioritize trauma as the indication for treatment in these instances, as it was likely trauma and not the associated diagnoses that instigated the use of rFVIIa.

The non-hemophilia hematologic conditions were divided into two groups. We gave high priority to primary clotting disorders that represent distinct and usually isolated defects in the clotting process. We gave lower priority to secondary clotting disorders that are more likely the end product of other pathological conditions, as with traumatic bleeding causing consumptive coagulopathy or the disruption of clotting produced by liver disease.

Projections

Statistical weights associated with each hospital by quarter were applied for projection of estimated rFVIIa use at the national level. Hospitals providing data for the Premier database represent a convenience sample and may differ from hospitals nationwide; however, the Premier database is the largest hospital-based, service-level comparative database in the country. Statistical weighting allows national projections to be made under the assumption that Premier hospitals of specific types resemble hospitals nationwide with these same characteristics. For each type of hospital (defined by size, region, teaching status, and ownership) weights are calculated as the inverse of the fraction of national admissions for this subgroup represented in Premier database. These aggregate national estimates are made using data from the American Hospital Association. This statistical weight assigned to each type of hospital by quarter allows derivation of national projections (for additional details, see ref. 26). While this is a relatively rudimentary adjusted projection strategy, it enables national projections that account for some, but not all, selection biases in the Premier sample. The statistical weights vary from around 10 per Premier-documented case in 2000 to around 5.5 in 2008 as a function of the increasing number of hospitals included in the database over time. For our sample of 12,644 hospitalizations, we projected 73,747 (95% CI, 51,247 to 96,245) cases of rFVIIa use nationwide during the study period.

Statistical methods

Our analyses identified annual trends in national in-hospital rFVIIa use. To characterize patterns of use by indication, we produced a cross-tabulation of indication category by year. We performed similar analyses for patient age, discharge disposition, and hospital characteristics. The unit of analysis was any “case” of rFVIIa use—defined as any hospitalization during which rFVIIa was administered one or more times. We chose this case-based unit of analysis because it captures the medical decision-making component of care about whether to use or not use rFVIIa for a given patient. Alternative methods of analysis by dosing were considered (e.g., volume of rFVIIa dispensed by the pharmacy) but were determined to have significant disadvantages: possible discrepancies between dispensed rFVIIa and the amount actually administered, lack of consistent hospital coding of rFVIIa dispensing, and outlier cases. Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We calculated 95% confidence intervals for counts of hospital cases and proportions using the SAS SURVEYMEANS procedure, which accounted for selection of a national sample of hospitals.

Results

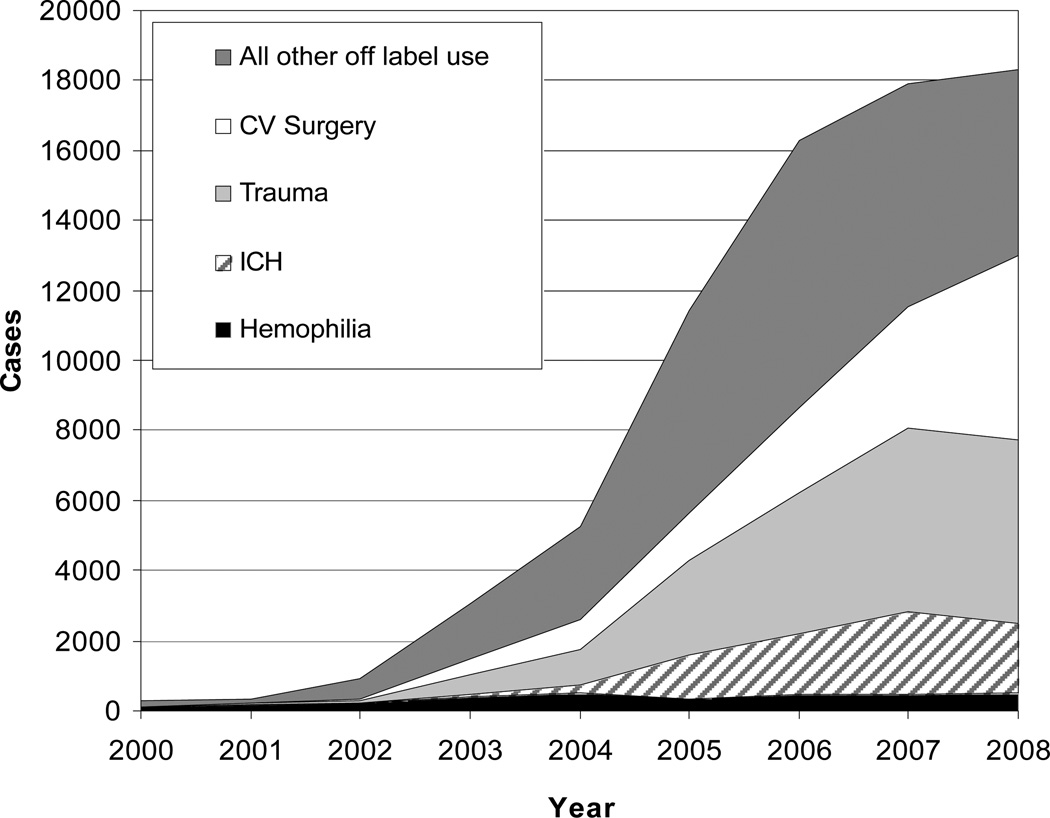

From 2000 through 2008, there were an estimated 73,747 (95% CI, 51,247 to 96,245) hospital cases in the U.S. where rFVIIa use was reported. Over this period, off-label rFVIIa cases increased 140-fold (Figure 1) from 125 (95% CI, 0 to 543) in 2000 to 17813 (95% CI, 14,381 to 22,240) in 2008. Use increased most rapidly for cardiovascular surgery and trauma. There have been more modest increases for non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), liver disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, and other off-label indications (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Estimated Annual In-Hospital Cases* of rFVIIa Use for Hemophilia and Off-Label Indications.

* Cases signify the number of hospitalizations during which rFVIIa was used. The graph depicts all cases for each year. The width of each segment represents the number of cases for each category as indicated by differential shading. Hemophilia = Hemophilia A and B; ICH = Non-Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage; Trauma = Body and Brain Trauma; CV = Cardiovascular.

Table 1.

Indications for In-Hospital Use of Recombinant Factor VIIa.

| Hospitalizations 2000–2008 |

Hospitalizations 2008 only |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Indication | Estimated Cases |

Percentage of Total |

Estimated Cases |

Percentage of Total |

| FDA approved indications | ||||

| Hemophilia A and B | 3121 | 4.2 | 498 | 2.7 |

| Off-label indications | ||||

| Adult cardiovascular surgery | 12086 | 16.4 | 4862 | 26.6 |

| Body trauma | 11689 | 15.9 | 3214 | 17.6 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 7755 | 10.5 | 2005 | 11.0 |

| Brain trauma | 7158 | 9.7 | 2033 | 11.0 |

| Primary clotting disorders | 4104 | 5.6 | 792 | 4.3 |

| Non-variceal GI bleeding | 3881 | 5.3 | 713 | 3.9 |

| Secondary clotting disorders | 3744 | 5.1 | 766 | 4.2 |

| Other liver disease | 2451 | 3.3 | 539 | 2.9 |

| Pediatric cardiovascular surgery | 1684 | 2.3 | 387 | 2.1 |

| Other vascular procedures | 1515 | 2.0 | 381 | 2.1 |

| Aortic aneurysm | 1216 | 1.6 | 306 | 1.7 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 1119 | 1.5 | 275 | 1.5 |

| Cancer/stem cell transplant | 1094 | 1.5 | 138 | 0.8 |

| Variceal bleeding | 897 | 1.2 | 235 | 1.3 |

| Liver biopsy/resection | 867 | 1.2 | 122 | 0.7 |

| Neonatal indications | 729 | 1.0 | 135 | 0.7 |

| Obstetrical hemorrhage | 672 | 0.9 | 220 | 1.2 |

| Neurosurgery | 500 | 0.7 | 108 | 0.6 |

| Liver transplantation | 132 | 0.2 | 58 | 0.3 |

| Prostatectomy | 120 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other procedures | 3867 | 5.2 | 407 | 2.2 |

| Other diagnoses | 3345 | 4.5 | 117 | 0.6 |

| Total treated with rFVIIa | 73747 | 100 | 18311 | 100 |

Hemophilia and related conditions

Initial use of rFVIIa was predominantly for the FDA-approved indications, including hemophilia A and B, as well as related (though not FDA-approved) conditions, such as other clotting factor deficiencies, von Willebrand disease and Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (“primary clotting disorders” in Table 1). Use for the hemophilias has increased 3.8-fold since 2000 but appears to have plateaued, while there has been a 7.4-fold increase in use for the other primary clotting disorders. These two groups remained the most common cluster of indications from 2000 through 2003, but their proportion of use fell from 93% (95% CI, 71% to 100%) of use in 2000 to 7.1% (95% CI, 5.3% to 8.8%) in 2008. Hemophilia A and B alone account for 4.2% (95% CI, 2.6% to 5.9%) of use overall and 2.7% (95% CI, 1.9% to 3.5%) of use in 2008.

Cardiovascular surgery

rFVIIa use in cardiovascular surgery was initially observed in 2002, and by 2008 was one of the most frequent and rapidly increasing indications. While use in pediatric cardiovascular surgery, largely for repair of congenital anomalies, has been modest (2.3% of uses overall and 2.1% in 2008), use in adult cardiovascular surgery, largely for aortic valve, mitral valve and CABG procedures, has rapidly increased, accounting for 16% (95% CI, 12% to 21%) of cases overall and 27% (95% CI, 21% to 33%) in 2008 (Table 1 and Appendix Figure 1).

Appendix Figure 1.

A, Estimated Annual In-Hospital Cases Using rFVIIa for Cardiovascular Surgery in the Adult and Pediatric Populations. B, Annual Use for Trauma and Intracranial Hemorrhage.

Trauma

Sizable use of rFVIIa for traumatic bleeding began in 2002, and it remained the dominant indication for off-label use until it was equaled in prevalence by cardiac surgery (adult and pediatric) in 2008. While use for body and brain trauma leveled off in 2008 (Table 1 and Appendix Figure 1), trauma other than brain trauma (“Body trauma” in Table 1) remains the second most common indication for rFVIIa use and accounts for 16% (95% CI, 8.3% to 23%) of overall 2000–08 use and 18% (95% CI, 12% to 23%) of use in 2008. Use in brain trauma, particularly traumatic subdural hematoma constitutes 9.7% (95% CI, 5.2% to 14%) of overall 2000–08 use and 11% (95% CI, 7.0% to 15%) of use in 2008.

Intracranial hemorrhage

rFVIIa use in non-traumatic ICH, particularly intracerebral hemorrhage, reached sizable scale in 2004. Use for this indication also has grown, with use in 2008 nearly 8-fold higher than was reported in 2004, although use fell slightly from 2007 to 2008 (Table 1 and Appendix Figure 1). ICH accounts for 11% (95% CI, 6.9% to 14%) of rFVIIa cases overall and 11% (95% CI, 7.7% to 14%) in 2008.

Liver disease

A range of indications related to liver disease account for 6% (95% CI, 2.5% to 9.3%) of all uses, including liver biopsy (1.2%), variceal bleeding (1.2%), liver transplant (0.2%), and other liver indications (3.3%).

Other conditions

Gastrointestinal bleeding other than that associated with esophageal varices or liver disease accounted for 5.3% (95% CI, 3.2% to 7.4%) of cases overall. Management of aortic aneurysm, in the presence and absence of surgical intervention, represented 1.7% of use overall and in 2008. Other conditions contributed minimally to rFVIIa use, including pulmonary indications, particularly biopsy and lung transplant (1.5% overall); cancer-related conditions, particularly leukemia (1.5%); neonatal indications (1%); obstetrical conditions, particularly post-partum hemorrhage (0.9%); and a number of surgical procedures, none of which were individually prominent (5.3% overall, 2.2% in 2008). A variety of secondary clotting disorders were associated with rFVIIa use (5.1% overall, 4.2% in 2008), including secondary thrombocytopenias and complications of warfarin anticoagulation.

Age distribution

Consistent with the growth of off-label indications, the mean age of patients has increased from 3 years (95% CI, 1.0 to 4.7 years) in 2000 to 59 years (95% CI, 56 to 61 years) in 2008. The age distribution of rFVIIa use varies by indication. Use for hemophilia A and B occurs predominantly in patients 25 years of age and younger (63%; 95% CI 48% to 77%). For ICH, 58% (95% CI, 55% to 61%) of use is in patients 65 years of age and older, with 36% (95% CI, 33% to 39%) in those 75 years and older. Other conditions where use in patients 65 years and older is prominent include aortic aneurysm (82%; 95% CI, 77% to 87%), prostatectomy (66%; 95% CI, 33% to 98%), brain trauma (58%; 95% CI 54% to 63%), cardiovascular surgery (57%; 95% CI 54% to 61%), and non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding (57%; 95% CI, 51% to 64%).

Discharge disposition

Overall in-hospital mortality among patients receiving rFVIIa was 27% (95% CI,19% to 34%). Only 43% (95% CI, 26% to 59%) of patients were discharged directly home (Table 2). Most of the remaining patients were transferred to other facilities (e.g., nursing homes and rehabilitation hospitals). Mortality increased from 5% (95% CI, 0% to 35%) in 2000 to a peak of 31% (95% CI, 24% to 37%) in 2004 but declined slightly to 27% (95% CI, 25% to 30%) in 2008. Mortality among patients with hemophilia A and B was 4% (95% CI, 1.8% to 5.8%). The highest mortality rates were associated with aortic aneurysm (54%; 95% CI, 43% to 65%), neonatal indications (47%; 95% CI, 35% to 59%), and non-variceal complications of liver disease (40%; 95% CI, 32% to 48%). Regarding the most common indications, mortality was 34% (95% CI, 31% to 38%) for spontaneous ICH, 33% (95% CI, 20% to 47%) for brain and body trauma, and 23% (95% CI, 21% to 26%) for adult cardiovascular surgery.

Table 2.

Disposition of Hospitalizations Involving Use of rFVIIa During 2000–2008.

| Indication | Total | Died* (%) | Other‡ (%) | Home (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic aneurysm | 1216 | 54.4 | 26.6 | 19.0 |

| Neonatal indications | 729 | 46.7 | 15.0 | 38.3 |

| Other liver disease | 2451 | 40.4 | 27.7 | 31.9 |

| Variceal bleeding | 897 | 39.0 | 28.8 | 32.2 |

| Other vascular procedures | 1515 | 38.5 | 30.3 | 31.2 |

| Liver transplant | 132 | 38.1 | 14.3 | 47.6 |

| Liver biopsy | 867 | 35.9 | 18.9 | 45.2 |

| Non-traumatic ICH | 7755 | 34.4 | 49.7 | 15.9 |

| Body trauma | 11689 | 33.1 | 36.7 | 30.2 |

| Brain trauma | 7158 | 33.1 | 44.2 | 22.7 |

| Secondary clotting disorders | 3744 | 30.1 | 28.6 | 41.3 |

| Non-variceal GI bleed | 3887 | 29.7 | 30.8 | 39.5 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 1119 | 24.5 | 29.7 | 45.8 |

| Adult CV surgery | 12086 | 23.3 | 28.5 | 48.2 |

| Pediatric CV surgery | 1684 | 21.7 | 5.0 | 73.3 |

| Primary clotting disorders | 4104 | 16.8 | 26.0 | 57.2 |

| Obstetrical hemorrhage | 672 | 14.6 | 7.8 | 77.6 |

| Cancer/Stem cell transplant | 1094 | 13.8 | 18.8 | 67.4 |

| Other procedures | 3867 | 9.4 | 26.0 | 64.6 |

| Other diagnoses | 3345 | 5.8 | 17.5 | 76.7 |

| Hemophilia A and B | 3121 | 3.8 | 11.4 | 84.8 |

| Prostatectomy | 120 | 0.0 | 19.1 | 80.9 |

In-hospital deaths.

Inter-hospital transfers and transfers to skilled nursing facilities or hospice.

CV=Cardiovascular; GI=Gastrointestinal; ICH=Intracranial Hemorrhage

Hospital characteristics

rFVIIa use was reported in 235 of the 615 hospitals (38%) represented in the Premier database. Most rFVIIa use occurred in non-academic hospitals (68% of use; 95% CI, 39% to 97%), a pattern that was consistent for the majority of the indications we studied (Figure 2). Over time, the proportion of rFVIIa use in non-academic hospitals grew from 11% (95% CI, 0% to 43%) in 2000 to a peak of 73% (95% CI, 31% to 71%) in 2005 followed by 67% (95% CI, 57% to 77%) in 2008. Off-label use of rFVIIa was lower at academic hospitals (92%; 95% CI, 88% to 96%) compared with non-academic hospitals (97%; 95% CI, 96% to 98%).

Figure 2.

Use of rFVIIa at Academic and Non-Academic Institutions During 2000–2008.

Comment

The potential for rFVIIa to be used as an emergency hemostatic agent outside the setting of hemophilia was recognized soon after its clinical introduction (10–11). Although this agent is currently approved by the FDA for certain uncommon conditions, its in-hospital use for these is now far exceeded by its use for off-label indications. Using a representative database of individual hospitalizations across the U.S., we found that 96% of all in-hospital cases of rFVIIa use between 2000 and 2008 and 97% of cases in the year 2008 were off-label. These findings are consistent with past reports (Appendix Table 2) (12–20).

Appendix Table 2.

Prevalence of Off–Label rFVIIa Use at Academic (Single or Multiple Institution) and Non-Academic Medical Centers.

| Study | Latest year included |

Setting | Cases | Off-label (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This report | 2008 | Academic/Non-academic | 12644* | 97.0 |

| Hsia, et al. (12) | 2007 | Academic (single) | 94 | 88.3 |

| Magnetti, et al. (13) | 2005 | Academic (multiple) | 2660 | 89.0 |

| Carcao, et al. (14) | 2005 | Academic (multiple) | 196 | 80.0 |

| Heller, et al. (15) | 2005 | Academic (single) | 111 | 79.0 |

| Webert, et al. (16) | 2005 | Academic/Non-academic | 85 | 83.6 |

| O'Connell, et al. (18) | 2004 | Academic/Non-academic‡ | 168 | 89.9 |

| MacLaren, et al. (19) | 2004 | Academic/Non-academic | 701 | 92.0 |

| Goodnough, et al. (20) | 2004 | Academic (single) | 130 | 93.8 |

Number of unweighted observations.

Subset of sample used for this report.

Adult cardiovascular surgery is the most rapidly emerging indication for rFVIIa use. In 2008, over one in four cases receiving rFVIIa were treated in the context of cardiovascular surgery. There is limited evidence to support this use. Diprose and colleagues reported a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 20 patients (9 received rFVIIa) in which a single dose of rFVIIa was used prophylactically at the termination of cardio-pulmonary bypass in non-coronary cardiovascular surgery (21). Although the need for allogeneic blood transfusion was significantly reduced after the administration of rFVIIa, there was no impact on patient survival. More recently, Gill and colleagues reported a placebo controlled RCT in which patients with bleeding after cardiovascular surgery were randomly assigned to a single dose of rFVIIa at 40 (n=35) or 80 (n=69) micrograms per kilogram versus placebo (n=68) (22). Significant decreases in the need for re-operation and allogeneic blood transfusions were seen in the groups receiving rFVIIa, but there were no differences in mortality. Furthermore, there were increases in thromboembolic adverse events, particularly stroke, in the rFVIIa groups, although they did not reach statistical significance.

The next leading indication for rFVIIa use, body trauma, accounted for 18% of use in 2008 and was addressed by two simultaneously reported RCTs. While these trials demonstrated a significant decrease in transfusion requirements and possible decrease in acute respiratory distress syndrome, they also censored patients who died within the first 48 hours of rFVIIa administration and yet demonstrated no mortality benefit (23). The recently published CONTROL trial, which was terminated early due to failure to demonstrate a mortality benefit with use of rFVIIa in blunt and penetrating trauma at a pre-planned interim analysis, suggest that other aspects of trauma management have improved sufficiently that mortality is not significantly affected by pro-coagulant administration, even with severe hemorrhage (24). Brain trauma and non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) each constituted 11% of use in 2008. Non-traumatic ICH is the subject of perhaps the best quality RCT in this field to date. Mayer and colleagues demonstrated no mortality or functional outcome benefit after early treatment of ICH with rFVIIa, in spite of evidence that this treatment reduced hematoma expansion (25). The results of this study may have contributed to the decline in rFVIIa use for ICH in 2008.

Together, the three major indications of cardiac surgery (adult and pediatric), trauma (body and brain), and non-traumatic ICH account for 55% cases of in-hospital rFVIIa use from 2000–2008 and 69% of cases in 2008. Remaining use is dispersed amongst a multitude of medical and surgical indications. Most of these have not been well-studied. Thus, use of rFVIIa is growing in the absence of clear evidence of therapeutic efficacy and without close surveillance for associated harms. In addition, we identified its use in 38% of hospitals, with a shift from academic (89% in 2000) to non-academic hospitals (67% in 2008), such that the bulk of overall rFVIIa use has occurred in non-academic settings (Figure 2). This suggests wide adoption of rFVIIa as a therapy in spite of concerns regarding its efficacy and safety.

We also have conducted a comparative effectiveness review of in-hospital, off-label use of rFVIIa for five indications which demonstrated no evidence of mortality reduction but an increased risk of arterial thromboembolic events in cardiovascular surgery and non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhage (26, and Yank, et al. in this issue of Annals). Levi and colleagues similarly confirmed an increase in arterial thrombotic adverse events amongst all published randomized controlled trials investigating off-label use of rFVIIa (27). Prior analyses of voluntary reports to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System identified deep vein thromboses, ischemic cerebrovascular accidents, and myocardial infarctions as the most common adverse events associated with rFVIIa use (17, 18). As noted by Aledort, rare adverse events may be not be clearly associated with an intervention based on an individual trial; however, meta-analysis of multiple trials may provide insight into the risk of rare events such as the thromboembolic adverse events that appear to be associated with off-label rFVIIa use (28). In the present study, we were unable to estimate the incidence of patient harm associated with rFVIIa use due to insufficient information in the Premier database on the temporal relationship between thromboembolic events and the use of rFVIIa.

An indirect measure of the efficacy of rFVIIa in the care of patients who receive it is survival to discharge. In the nationwide sample of hospitals we analyzed, in-hospital mortality for patients receiving rFVIIa was high—27% overall, and as high as 40–50% for several indications (Table 2). In-hospital mortality has been noted to be higher in retrospective studies of rFVIIa use outside of clinical trials as compared to that seen in carefully selected clinical trial populations (7, 12, 26, 29–30).

This study has several limitations. The Premier Perspectives database we queried gathers data from a voluntary alliance of non-federal hospitals and thus is not a random selection of healthcare facilities nation-wide. Our analysis of indications associated with use of rFVIIa was confined to the primary and secondary diagnoses (as listed by ICD-9 code) reported for each hospitalization. We cannot validate these diagnoses, nor can we identify diagnostic codes that may have been omitted. In addition, the indication hierarchy we used to categorize rFVIIa use may not have captured the nuances of each individual case. For instance, we are unable to determine at what point in a disease process rFVIIa was used (e.g, as prophylaxis, treatment, or for end-stage catastrophic bleeding). We also did not have access to data on patients with similar clinical scenarios where rFVIIa was not used.

Although it is to be expected that utilization of medications will change over time as additional hypotheses regarding patient therapeutics are examined, the key question is at what point a new indication has attained sufficient evidence-base to justify greatly expanded use. Given the absence of supporting data and the suggestion of patient harm, our analysis has identified probable nationwide overuse of rFVIIa outside the conditions approved by the FDA. We hope that this and other similar analyses of “real-world” medication use will provide guidance for the design of clinical trials and evidence reviews that adequately address the efficacy and associated harms of individual agents in the contexts in which they are most commonly employed. If concerning patterns of off-label use exist for other medications, these analyses may also help highlight areas for improvement in systems responsible for drug-approval and subsequent surveillance.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer: This project was funded under Contract No. #290-02-0017 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Stafford also was supported by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) mentoring award (RSS, K24HL086703). For their contributions to an associated comparative effectiveness review commissioned by AHRQ, we thank C. Vaughan Tuohy, Dena Brevata, Kristan Staudenmayer, Robin Eisenhut, Vandana Sundaram, Donal McMahon, David Johnston, Christopher Stave, James Zehnder, Ingram Olkin, Kathryn McDonald, and Douglas Owens.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures:

Over the past five years, Dr. Stafford reports past honoraria from Bayer, and past grant funding from Procter and Gamble, Bayer, Merck and Company, SmithKlineGlaxo, Toyo Shinyaku, and Wako Chemical USA. Drs. Logan and Yank have no disclosures.

Data access

Protocol: Available from the AHRQ website at http://www.ahrq.gov/

Statistical Code: Available to interested readers by contacting Dr. Stafford at rstafford@stanford.edu.

Data: Available for purchase from Premier, Inc., 13034 Ballantyne, Corporate Place, Charlotte, NC 28277

References

- 1.Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use—rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1427–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0802107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedner U. Factor VIIa and its potential therapeutic use in bleeding-associated pathologies. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:557–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts HR, Monroe DM, White GC. The use of recombinant factor VIIa in the treatment of bleeding disorders. Blood. 2004;104:3858–3864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts HR, Monroe DM, Hoffman M. Safety profile of recombinant factor VIIa. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:101–108. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas GO, Dutton RP, Hemlock B, Stein DM, Hyder M, Shere-Wolfe R, Hess JR, Scalea TM. Thromboembolic complications associated with factor VIIa administration. J Trauma. 2007;62:564–569. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318031afc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diringer MN, Skolnick BE, Mayer SA, Steiner T, Davis SM, Brun NC, Broderick JP. Risk of thromboembolic events in controlled trials of rFVIIa in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:850–856. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.493601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsia CC, Chin-Yee IH, McAlister VC. Use of recombinant activated factor VII in patients without hemophilia: A meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Ann Surg. 2008;248:61–68. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176c4ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diringer MN, Skolnick BE, Mayer SA, Steiner T, Davis SM, Brun Nc, Broderick JP. Thromboembolic events with recombinant activated factor VII in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: Results from the Factor Seven for Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke (FAST) Trial. Stroke. 2010;41:48–53. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howes JL, Smith RS, Helmer SD, Taylor SM. Complications of recombinant activated human coagulation factor VII. Am J Surg. 2009;198:895–899. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodnough LT. Treatment of critical bleeding in the future intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(suppl 2):S221. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer SA. Ultra-early hemostatic therapy for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34:224–229. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000046458.67968.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsia CC, Zurawska JH, Tong MZY, Eckert K, McAlister VC, Chin-Yee IH. Recombinant activated factor VII in the treatment of non-haemophilia patients: physician under-reporting of thromboembolic adverse events. Transfus Med. 2009;19:43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnetti S, Oinonen M, Matuszewski KA. An evalutation of off-label use of recombinant activated human factor VII (NovoSeven): Patient characteristics, utilization trends, and outcomes from an electronic database of US academic health centers. P&T. 2007;32:218–230. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carcao MD, Webert KE. On-label versus off-label use of recombinant activated factor VII: A comprehensive review of use in two Canadian centers. Semin Hematol. 2008;45(suppl 1):S68–S71. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller M, Lau W, Pazmino-Canizares J, Brandao LR, Carcao M. A comprehensive review of rFVIIa use in a tertiary care pediatric center. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1013–1017. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webert KE, Arnold DM, Carruthers J, Molnar L, Almonte T, Decker K, Seroski W, Reed J, Chan AK, Pai M, Walker IR. Utilization of recombinant activated factor VII in southern Ontario in 85 patients with and without haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2007;13:518–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aledort LM. Comparative thrombotic event incidence after infusion of recombinant factor VIIa versus factor VIII inhibitor bypass activity. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1700–1708. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connell KA, Wood JJ, Wise RP, Lozier JN, Braun MM. Thromboembolic adverse events after use of recombinant human coagulation factor VIIa. JAMA. 2006;295:293–298. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacLaren R, Weber LA, Brake H, Gardner MA, Tanzi M. A multicenter assessment of recombinant factor VIIa off-label usage: Clinical experiences and associated outcomes. Transfusion. 2005;45:1434–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodnough LT, Lublin DM, Zhang L, Despotis G, Eby C. Transfusion medicine service policies for recombinant factor VIIa administration. Transfusion. 2004;44:1325–1331. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diprose P, Herbertson MJ, O'Shaughnessy D, Gill RS. Activated recombinant factor VII after cardiopulmonary bypass reduces allogeneic transfusion in complex non-coronary cardiac surgery: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:596–602. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill R, Herbertson M, Vuylsteke A, Olsen PS, von Heymann C, Mythen M, Sellke F, Booth F, Schmidt TA. Safety and efficacy of recombinant activated factor VII: A randomized placebo-controlled trial in the setting of bleeding after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;120:21–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.834275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boffard KD, Riou B, Warren B, Choong PI, Rizoli S, Rossaint R, Axelsen M, Kluger Y. Recombinant factor VIIa as adjunctive therapy for bleeding control in severely injured trauma patients: Two parallel randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials. J Trauma. 2006;59:8–15. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000171453.37949.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauser CJ, Boffard K, Dutton R, Bernard GR, Croce MA, Holcomb JB, Leppaniemi A, Parr M, Vincent J-L, Tortella BJ, Dimsits J, Bouillon B. Results of the CONTROL trial: Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII in the management of refractory traumatic hemorrhage. J Truama. 2010;69:489–500. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181edf36e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begtrup K, Broderick J, Davis S, Diringer MN, Skolnick BE, Steiner T. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2127–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yank V, Tuohy CV, Logan AC, Bravata DM, Staudenmayer K, Eisenhut R, Sundaram V, McMahon D, Stave CD, Zehnder JL, Olkin I, McDonald KM, Owens DK, Stafford RS. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. Comparative Effectiveness of Recombinant Factor VIIa for Off-Label Indications versus Usual Care. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. X. (Prepared by Stanford-UCSF Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. #290-02-0017) Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levi M, Levy JH, Andersen HF, Truloff D. Safety of recombinant activated factor VII in randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1791–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aledort LM. Off-label use of recombinant activated factor VII — safe or not safe? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1853–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1008857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganguly S, Spengel K, Tilzer LL, O'Neal B, Simpson SQ. Recombinant factor VIIa: Unregulated continuous use in patients with bleeding and coagulopathy does not alter mortality and outcome. Clin Lab Haem. 2006;28:309–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardy J-F, Belisle S, Van der Linden P. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII to control bleeding in nonhemophiliac patients: A Review of 17 randomized controlled trials. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]