Abstract

Background and objectives

Patients receiving hemodialysis often perceive their caregivers are overburdened. We hypothesize that increasing hemodialysis frequency would result in higher patient perceptions of burden on their unpaid caregivers.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In two separate trials, 245 patients were randomized to receive in-center daily hemodialysis (6 days/week) or conventional hemodialysis (3 days/week) while 87 patients were randomized to receive home nocturnal hemodialysis (6 nights/week) or home conventional hemodialysis for 12 months. Changes in overall mean scores over time in the 10-question Cousineau perceived burden scale were compared.

Results

In total, 173 of 245 (70%) and 80 of 87 (92%) randomized patients in the Daily and Nocturnal Trials, respectively, reported having an unpaid caregiver at baseline or during follow-up. Relative to in-center conventional dialysis, the 12-month change in mean perceived burden score with in-center daily hemodialysis was −2.1 (95% confidence interval, −9.4 to +5.3; P=0.58). Relative to home conventional dialysis, the 12-month change in mean perceived burden score with home nocturnal dialysis was +6.1 (95% confidence interval, −0.8 to +13.1; P=0.08). After multiple imputation for missing data in the Nocturnal Trial, the relative difference between home nocturnal and home conventional hemodialysis was +9.4 (95% confidence interval, +0.55 to +18.3; P=0.04). In the Nocturnal Trial, changes in perceived burden were inversely correlated with adherence to dialysis treatments (Pearson r=−0.35; P=0.02).

Conclusion

Relative to conventional hemodialysis, in-center daily hemodialysis did not result in higher perceptions of caregiver burden. There was a trend to higher perceived caregiver burden among patients randomized to home nocturnal hemodialysis. These findings may have implications for the adoption of and adherence to frequent nocturnal hemodialysis.

Keywords: daily hemodialysis, outcomes, randomized controlled trials

Introduction

Frequent hemodialysis has the potential to provide multiple physiologic and quality of life benefits to patients with ESRD. In the Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Daily Trial, patients randomized to six times per week in-center hemodialysis experienced a significant improvement in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), left ventricular mass, and several other surrogate outcomes (1,2). Results from the FHN Nocturnal Trial were mixed; definitive conclusions were difficult to reach owing to insufficient sample size (3).

Although frequent hemodialysis may yield benefits, it is not without meaningful risks. Vascular access procedures were significantly more common (4), and the rate of decline of residual kidney function also seemed to accelerate (5). In contrast to the focus on physiologic effects of frequent hemodialysis (6,7), research into the personal, social, and psychologic effects of the therapy has attracted far less attention.

Six times per week in-center hemodialysis necessitates that patients come to the dialysis unit twice as often, with friends and family members often bearing the responsibility of driving or arranging transportation for them. Patients receiving hemodialysis at home must learn how to administer their own treatments, with caregivers often assisting partially or fully. The setup, takedown, and machine cleaning process can take 30–60 minutes each treatment. If home treatments are increased from 3 days to 6 nights per week, the increased workload could result in greater burden on patients as well as their caregivers. Higher perceptions of burden by patients on their caregivers could potentially result in therapy refusal and nonadherence.

We previously showed that more than 50% of participants in the FHN trials had unpaid caregivers at baseline, that the majority perceived a high degree of burden on their caregivers, and that higher perceived burden was associated with poorer HRQoL and more prominent depressive symptoms (8). We followed patients after randomization in the FHN trials to determine how perceived burden would change over time and in response to frequent dialysis therapy. We hypothesized that increasing dialysis frequency from three to six times per week would significantly increase the burden on caregivers as perceived by patients. We also hypothesized that perceived caregiver burden would be directly associated with depressive symptoms and inversely associated with self-reported physical and mental health and adherence to dialysis.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design

The FHN trials have been described in detail elsewhere (1). In the Daily Trial, 245 patients from 11 sites in the United States and Canada were randomized to receive either daily hemodialysis (1.5–2.75 hours per session, 6 days/week) or conventional hemodialysis (2.5–4.5 hours per session, 3 days/week). Both groups received their hemodialysis treatments in outpatient settings. In the Nocturnal Trial, 87 patients from eight centers in the United States and Canada were randomized to receive either nocturnal hemodialysis (at least 6 hours, 6 nights/week) or conventional hemodialysis. For this trial, patients and/or their caregivers were trained to perform hemodialysis at home. Patients were followed for 12 months. Both trials were approved by local Institutional Review or Research Ethics Boards, and all enrolled patients provided informed consent for participation. These trials were registered at Clinical Trials.gov (NCT00264758 and NCT00271999).

Questionnaires and Other Data Collection

During the baseline enrollment period, data were collected on demographics, comorbidities, laboratory variables, and dialysis prescription. Patients also completed several questionnaires that were centrally administered by telephone before randomization and 4 (F4) and 12 months (F12) after randomization. These questionnaires included the Cousineau scale of perceived burden. The Cousineau scale is a 10-item questionnaire originally developed in patients on hemodialysis (9). It assesses the degree to which patients perceive themselves as a burden on unpaid caregivers. Questions are answered on a five-point Likert scale, summed, and normalized to create an overall score ranging from 0 (no burden) to 100 (maximum burden). We previously reported on Cousineau scores and their correlates for all enrolled patients in the FHN trials (8).

Patients also completed the RAND 36-item health survey (RAND-36) and Beck depression inventory (BDI) as previously described (1), which were also centrally administered by telephone. The RAND-36 is a 36-item questionnaire assessing HRQoL with scores ranging from 0 (poorest HRQoL) to 100 (best HRQoL), and it has been previously validated in patients receiving dialysis. Self-reported physical and mental health were summarized with the RAND physical health composite (PHC) and mental health composite (MHC) scores (10). The BDI is a validated 21-item questionnaire assessing probability of depression, with scores ranging from 0 to 63; a score of 14–16 or higher is highly suggestive of clinical depression in patients receiving dialysis (11).

In the Daily Trial, patients completed questions regarding the time that they spent traveling to and waiting for hemodialysis sessions at baseline and months 4, 8, and 12. For patients with missing data, the baseline travel time was carried forward and multiplied by the average number of treatments per week actually received at 12 months. Finally, attendance at all hemodialysis sessions was recorded for both trials, and dialysis run-sheets were reviewed to monitor adherence to the prescriptions.

Statistical Analyses

Results from each trial were analyzed separately. The analytic population for this study was restricted to those patients from each trial who reported having unpaid caregivers at any ascertainment time point. Baseline characteristics were expressed as mean (±SD), median (10th and 90th percentiles), or proportion of patients (%); t, Wilcoxon rank sum, chi-squared, and Fisher exact tests were used, as appropriate, to compare baseline characteristics of the analytic cohort between randomized groups as well as between patients with missing and complete data within treatment groups.

The effects of randomized treatment assignment on the Cousineau burden score were estimated with mixed effects models incorporating baseline and 4- and 12-month values, and they assumed an unstructured covariance matrix. Effects were adjusted for time interactions with outcomes levels at baseline and 4 months and for the Daily Trial, clinical center. In sensitivity analyses, mean changes in Cousineau scores were compared between randomized groups after imputing missing scores for patients who did not deny having an unpaid caregiver. Missing Cousineau scores were imputed five times using a Monte Carlo Markov Chain algorithm assuming multivariate normality. The predictor variables used in the imputation model were the preceding Cousineau score, scores on the RAND-36 PHC and MHC and the BDI, and the number of different medication types taken during the ascertainment month. Statistical inferences for the multiply imputed data were performed using the standard adjustments to SEMs of Little and Rubin (12).

We a priori defined five factors as potential mediators for changes in Cousineau scores: adherence (defined as the percentage of sessions attended of the number anticipated for each assigned treatment group), travel time, and overall scores on the PHC, MHC, and BDI. We tested for associations among 12-month changes in these factors and the Cousineau score using Pearson correlations.

Two-tailed P values<0.05 were considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

In total, 173 of 245 (70%) and 80 of 87 (92%) randomized participants in the Daily and Nocturnal Trials, respectively, reported having an unpaid caregiver at baseline or follow-up (analytic cohort). Among patients with unpaid caregivers, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between randomized groups in either trial, including baseline Cousineau scores (Table 1). Of 62 caregivers for whom data were available on relationship, 76% were spouses, and 13% were defined as patients as significant others. Only 6% were children.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Daily Trial Analytic Cohorta | P Value | Nocturnal Trial Analytic Cohorta | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three Times per Week (n=77) | Six Times per Week (n=96) | Three Times per Week (n=39) | Six Times per Week (n=41) | |||

| Age, yr | 51.2±13.9 | 50.8±13.7 | 0.83 | 55.0±12.2 | 52.6±14.4 | 0.42 |

| Men | 43 (56%) | 54 (56%) | 0.96 | 25 (64%) | 27 (66%) | 0.87 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 27 (35%) | 38 (40%) | 0.54 | 9 (23%) | 11 (27%) | 0.69 |

| White | 34 (44%) | 33 (34%) | 0.19 | 21 (54%) | 24 (59%) | 0.67 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 24 (31%) | 29 (30%) | 0.89 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | — |

| Duration of ESRD, yr | 3.5 (1.8, 6.9) | 3.6 (1.4, 8.1) | 0.85 | 0.5 (0.2, 3.6) | 1.3 (0.3, 3.3) | 0.29 |

| Diabetes | 36 (47%) | 46 (48%) | 0.88 | 18 (46%) | 17 (42%) | 0.67 |

| Hypertension | 72 (94%) | 89 (93%) | 0.84 | 36 (92%) | 38 (93%) | 0.95 |

| Serum album (g/dl) | 3.9±0.5 | 3.9±0.4 | 0.78 | 3.9±0.5 | 3.9±0.5 | 0.81 |

| Cousineau score | 37.7±23.0 | 37.1±27.6 | 0.90 | 32.9±18.3 | 32.0±19.7 | 0.85 |

| Beck depression inventory | 13.5±9.9 | 13.4±9.1 | 0.95 | 11.7±8.7 | 10.9±8.0 | 0.69 |

| RAND-36 PHC | 35.8±9.3 | 36.0±10.7 | 0.91 | 38.0±8.6 | 37.3±9.7 | 0.76 |

| RAND-36 MHC | 44.8±9.9 | 42.7±13.5 | 0.25 | 47.0±11.3 | 46.1±10.4 | 0.72 |

| Travel time to dialysis, min | 20.0 (15.0, 30.0) | 23.5 (15.0, 30.0) | 0.85 | 30.0 (20.0, 59.0) | 30.0 (15.0, 45.0) | 0.33 |

Values are means±SDs or medians (25th, 75th percentiles). PHC, physical health composite; MHC, mental health composite.

The analytic cohort is those patients that had a Cousineau score at any point during baseline or follow-up.

Missing Data

In the Daily Trial, 123 patients had Cousineau scores available at baseline. Of these patients, 58 of 65 (89%) patients from the daily group and 47 of 58 (81%) patients from the conventional group had follow-up data available at either F4 or F12 (Figure 1A). Of 18 patients without any follow-up scores, 6 patients died or were transplanted. In the Nocturnal Trial, 65 patients had Cousineau scores at baseline. Of these patients, 26 of 33 (79%) from the nocturnal group and 29 of 32 (91%) from the conventional group had follow-up data available at either F4 or F12 (Figure 1B). Of 10 patients without any follow-up scores, 3 patients died or were transplanted. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics among patients who had complete versus missing data in either trial, with the exception of slightly higher PHC scores in patients with missing data in the Nocturnal Trial (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants. Bold text indicates those participants included in the final analytic cohort. F, months after randomization. B, baseline.

Changes in Cousineau Perceived Burden Scores

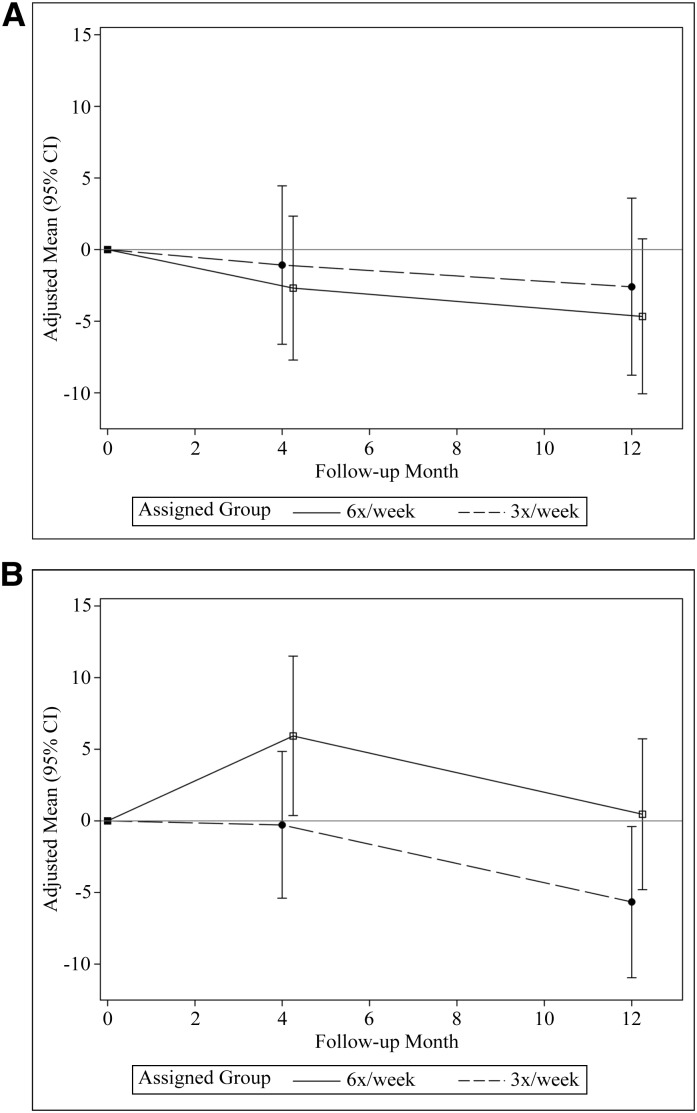

Figure 2 and Table 2 show mean Cousineau questionnaire scores at baseline and adjusted mean scores at months 4 and 12 in both trials. Over 12 months, the relative change in mean perceived burden score was −2.1 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 9.4 to +5.3; P=0.58) in patients randomized to in-center frequent hemodialysis and +6.2 (95% CI, −0.8 to +13.1; P=0.08) in patients randomized to home nocturnal frequent hemodialysis relative to conventional hemodialysis. With imputation of missing data, the comparison in the Nocturnal Trial was statistically significant: +9.4 (95% CI, +0.55 to +18.3; P=0.04) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in perceived Cousineau score over time in the (A) Daily Trial and (B) Nocturnal Trial. Y axis indicates mean change in Cousineau burden score. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 2.

Cousineau perceived burden scores over time

| Time Point | Three Times per Week | Six Times per Week | Between-Group Differencea | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Trial | ||||

| Baseline | 37.7±23.0 | 37.1±27.6 | ||

| Month 4 | 35.0±22.7 | 32.9±25.1 | ||

| Change from baseline | −1.1±2.8 | −2.7±2.5 | −1.6 (−8.4 to 5.2) | 0.64 |

| Change (imputed) | 1.8±4.3 | 0.6±4.1 | −1.2 (−8.0 to 5.6) | 0.73 |

| Month 12 | 31.2 ±21.9 | 30.1±22.9 | ||

| Change from baseline | −2.6±3.1 | −4.7±2.7 | −2.1 (−9.4 to 5.3) | 0.58 |

| Change (imputed) | 1.2±4.7 | −1.5±4.4 | −2.7 (−9.8 to 4.4) | 0.46 |

| Nocturnal Trial | ||||

| Baseline | 32.9±18.3 | 32.0±19.7 | ||

| Month 4 | 32.0±16.9 | 41.1±18.5 | ||

| Change from baseline | −0.3±2.6 | +5.9±2.8 | +6.2 (−0.8 to 13.3) | 0.08 |

| Change (imputed) | −0.3±2.8 | +9.6±3.0 | +9.8 (2.4 to 17.3) | 0.01 |

| Month 12 | 26.9±15.3 | 33.9±22.0 | ||

| Change from baseline | −5.7±2.7 | +0.5±2.7 | +6.1 (−0.8 to 13.1) | 0.08 |

| Change (imputed) | −5.4±3.1 | +4.0±3.4 | +9.4 (0.6 to 18.3) | 0.04 |

Values at baseline, 4 months postrandomization, and 12 months postrandomization are observed means±SDs. Changes from baseline are adjusted means (presented as means±SEM).

Treatment effect of six times per week minus three times per week (presented with 95% confidence intervals).

Correlates of Changes in Cousineau Score

In the Daily Trial, changes in Cousineau questionnaire scores from baseline to 12 months were inversely correlated with changes in the RAND-36 PHC and MHC scores and directly correlated with changes in BDI scores (Table 3). In the Nocturnal Trial, changes in Cousineau questionnaire scores from baseline to 12 months were inversely correlated with overall adherence to the prescribed dialysis treatment (Table 3). There was no correlation with travel time in either trial.

Table 3.

Correlates of 12-month changes in Cousineau score

| Scalea | Daily Trial | Nocturnal Trial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson r | P Value | Pearson r | P Value | |

| Beck depression index | 0.49b | <0.001 | −0.03 | 0.83 |

| RAND PHC | −0.28b | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.07 |

| RAND MHC | −0.32b | 0.01 | −0.29 | 0.05 |

| Weekly travel time | −0.01 | 0.91 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| Adherence to dialysisc | 0.13 | 0.28 | −0.35b | 0.02 |

Correlates of 12-month changes in Cousineau score are with the 12-month change in each scale.

Statistically significant.

Measured as the percent of prescribed treatments actually attended.

Discussion

Patients receiving dialysis exist amid a complex milieu of supports, including physicians, nurses, allied health professionals, other patients, family, and friends, and interactions between these people may potentially influence patient outcomes (13). Compared with other chronic diseases, the burden on caregivers of patients receiving hemodialysis has not been studied extensively (14), which is surprising, given the extent to which patients receiving hemodialysis rely on unpaid caregivers for many of their daily tasks. These tasks may include driving to dialysis and other medical appointments, administration of medications, meal preparation, maintenance of personal hygiene, etc. Although increasing the frequency of hemodialysis may improve patient HRQoL and surrogate markers of health (2,3), more frequent hemodialysis may increase the burden on unpaid caregivers. We have previously shown that the degree to which a patient perceives his or her caregiver as being burdened is associated with measures of HRQoL and depression (8). Patient perceptions of high burden could also lead to feelings of hopelessness and despair. In Oregon, of 56 patients requesting physician aid in dying, more than one half cited the inability to care for oneself and not wanting others to care for them as very important reasons for their decision (15). Thus, any increases in perceived burden with frequent hemodialysis could have implications for long-term adherence to an already demanding therapy. Others have shown that perceived caregiver burden is a main barrier to acceptance of home nocturnal hemodialysis (16).

In these randomized trials, we surprisingly found that frequent in-center daily hemodialysis did not result in higher perceptions of burden compared with conventional hemodialysis after 4 or 12 months. Mean perceived caregiver burden scores as measured by the Cousineau scale decreased modestly over 12 months in both groups. Conversely, in the Nocturnal Trial, there were trends to higher mean scores at 4 and 12 months in the nocturnal compared with the conventional group, which were statistically significant after imputation. What does the six- to nine-point between-group difference that was observed in the Nocturnal Trial mean? Although changes in Cousineau scores have not been validated against hard outcomes in the literature, this degree of change has face validity as being clinically important. An eight-point change represents a full change in response in at least one question (from all of the time to none of the time) or a change in response of at least one level (from all of the time to most of the time or from most of the time to a little of the time, etc.) in at least four questions. Unfortunately, we were not able to gather data with respect to the caregivers themselves to determine if patient perceptions in burden were accurate. Additional research in this area is warranted.

We can speculate as to why in-center daily hemodialysis did not result in increased perceived burden over time. It is possible that any increases in caregiver burden caused by increased dialysis frequency may have been offset by decreases in burden because of improvements in patients’ health. Patients receiving in-center daily hemodialysis experienced some improvements in physiologic function and HRQoL, and thus, they may have been more able to take on some of the daily activities previously performed by their caregivers. Alternatively, it may have been that patients receiving in-center daily hemodialysis felt a sense of security by coming to the dialysis unit two times as often. They may have also perceived that paid health care workers were now bearing more of the burden of their care than their unpaid caregivers. It should be noted that the Daily Trial participants were younger, on average, than the hemodialysis population in North America. Our results may have been different in an older population, in which patients tend to be more dependent on their unpaid caregivers.

The results from the Nocturnal Trial were not statistically significant, possibly because of low statistical power. It is possible that denial may have played a role when patients responded to the questionnaires in this experimental setting. The fact that there was a trend to higher perceived burden with 6 nights/week therapy than 3 days/week therapy at both time points is not surprising, given the considerable amount of work each hemodialysis treatment entails. Unlike in-center daily dialysis, which mainly involves the burden of increased travel time, home dialysis involves a multitude of tasks that must be completed accurately by the patient and his or her caregivers, with potentially more stress and burden. In addition, if social support from seeing other dialysis patients, other patients’ family members, and staff in the dialysis unit regularly is important in alleviating perceptions of caregiver burden, the absence of these factors for patients dialyzing at home may partly explain the differences that we observed between the two trials.

There was a direct correlation between changes in depressive symptoms and changes in perceived caregiver burden and inverse correlations among changes in self-report physical and mental health and changes in perceived caregiver burden. These data suggest that increasing perception of burden was associated with patient depressive affect and decreased perception of HRQoL. We cannot determine whether perceived caregiver burden contributed to depression or poorer health status, which is certainly feasible, or whether poorer physical or mental health status obligated more perceived and real effort on the part of caregivers. The inverse correlation between adherence and perceived caregiver burden in the Nocturnal Trial is not surprising, because the therapy was administered at home. The perceived and real burden may have been substantial enough that treatments were missed by either necessity or frustration.

Our study has several strengths. We used a randomized design to compare differences in perceived burden among patients receiving frequent and conventional hemodialysis. We used a scale that was developed and validated in hemodialysis patients. Finally, we were able to correlate changes in perceived burden with changes in other important variables.

We recognize that our study has several limitations. The sample size in the Nocturnal Trial was small. Although we made all possible efforts to avoid missing data, our missing data rates were between 9% and 21% (8%–16% accounting for deaths and transplants). However, it is reassuring that results were similar after multiple imputations. We were not able to obtain data from the caregivers themselves with respect to their own perceptions of the burden that they bear, their HRQoL, their comorbidities, or other health indices, and we do not have information on what tasks they were performing. Future studies should examine the effects of frequent hemodialysis on the attitudes of caregivers themselves, which tasks are associated with the highest burden, and what factors, if any, may alleviate caregiver burden in dialysis patients.

Relative to conventional hemodialysis, in-center daily hemodialysis did not result in higher perceptions of caregiver burden. However, compared with home conventional hemodialysis, patients receiving home nocturnal hemodialysis may perceive greater burden on their unpaid caregivers. This perception may have effects on long-term adoption of and adherence to nocturnal hemodialysis.

Disclosures

R.S.S. has an unrestricted research grant from Baxter, Inc. G.M.C. is a member of the Board of Directors of Satellite Healthcare and a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of DaVita Clinical Research.

Acknowledgments

The investigators and sponsors are grateful for the support of contributors to the National Institutes of Health Foundation (Amgen, Baxter, Inc., and Dialysis Clinics) and the support from Fresenius Medical Care. We thank the patients who participated in the study.

R.S.S. is funded by a scholarship from the Fonds de recherche du Québec Santé. This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the National Institutes of Health Research Foundation.

References 2 and 3 list all of authors in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trial Group.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07170713/-/DCSupplemental.

See related editorial, “Caregiver Burden and Hemodialysis,” on pages 840–842.

References

- 1.Suri RS, Garg AX, Chertow GM, Levin NW, Rocco MV, Greene T, Beck GJ, Gassman JJ, Eggers PW, Star RA, Ornt DB, Kliger AS, Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trial Group : Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) randomized trials: Study design. Kidney Int 71: 349–359, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chertow GM, Levin NW, Beck GJ, Depner TA, Eggers PW, Gassman JJ, Gorodetskaya I, Greene T, James S, Larive B, Lindsay RM, Mehta RL, Miller B, Ornt DB, Rajagopalan S, Rastogi A, Rocco MV, Schiller B, Sergeyeva O, Schulman G, Ting GO, Unruh ML, Star RA, Kliger AS, FHN Trial Group : In-center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med 363: 2287–2300, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rocco MV, Lockridge RS, Jr., Beck GJ, Eggers PW, Gassman JJ, Greene T, Larive B, Chan CT, Chertow GM, Copland M, Hoy CD, Lindsay RM, Levin NW, Ornt DB, Pierratos A, Pipkin MF, Rajagopalan S, Stokes JB, Unruh ML, Star RA, Kliger AS, Kliger A, Eggers P, Briggs J, Hostetter T, Narva A, Star R, Augustine B, Mohr P, Beck G, Fu Z, Gassman J, Greene T, Daugirdas J, Hunsicker L, Larive B, Li M, Mackrell J, Wiggins K, Sherer S, Weiss B, Rajagopalan S, Sanz J, Dellagrottaglie S, Kariisa M, Tran T, West J, Unruh M, Keene R, Schlarb J, Chan C, McGrath-Chong M, Frome R, Higgins H, Ke S, Mandaci O, Owens C, Snell C, Eknoyan G, Appel L, Cheung A, Derse A, Kramer C, Geller N, Grimm R, Henderson L, Prichard S, Roecker E, Rocco M, Miller B, Riley J, Schuessler R, Lockridge R, Pipkin M, Peterson C, Hoy C, Fensterer A, Steigerwald D, Stokes J, Somers D, Hilkin A, Lilli K, Wallace W, Franzwa B, Waterman E, Chan C, McGrath-Chong M, Copland M, Levin A, Sioson L, Cabezon E, Kwan S, Roger D, Lindsay R, Suri R, Champagne J, Bullas R, Garg A, Mazzorato A, Spanner E, Rocco M, Burkart J, Moossavi S, Mauck V, Kaufman T, Pierratos A, Chan W, Regozo K, Kwok S, Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Trial Group : The effects of frequent nocturnal home hemodialysis: The Frequent Hemodialysis Network Nocturnal Trial. Kidney Int 80: 1080–1091, 2011. 21775973 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suri RS, Larive B, Sherer S, Eggers P, Gassman J, James SH, Lindsay RM, Lockridge RS, Ornt DB, Rocco MV, Ting GO, Kliger AS, Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trial Group : Risk of vascular access complications with frequent hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 498–505, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daugirdas JT, Greene T, Rocco MV, Kaysen GA, Depner TA, Levin NW, Chertow GM, Ornt DB, Raimann JG, Larive B, Kliger AS, FHN Trial Group : Effect of frequent hemodialysis on residual kidney function. Kidney Int 83: 949–958, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suri RS, Nesrallah GE, Mainra R, Garg AX, Lindsay RM, Greene T, Daugirdas JT: Daily hemodialysis: A systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 33–42, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh M, Culleton B, Tonelli M, Manns B: A systematic review of the effect of nocturnal hemodialysis on blood pressure, left ventricular hypertrophy, anemia, mineral metabolism, and health-related quality of life. Kidney Int 67: 1500–1508, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suri RS, Larive B, Garg AX, Hall YN, Pierratos A, Chertow GM, Gorodetskeya I, Kliger AS, FHN Study Group : Burden on caregivers as perceived by hemodialysis patients in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 2316–2322, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cousineau N, McDowell I, Hotz S, Hébert P: Measuring chronic patients’ feelings of being a burden to their caregivers: Development and preliminary validation of a scale. Med Care 41: 110–118, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hays RD, Morales LS: The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med 33: 350–357, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimmel PL, Cukor D, Cohen SD, Peterson RA: Depression in end-stage renal disease patients: A critical review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 328–334, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Little RJA, Rubin DB, editors: Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, New York, Wiley, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cukor D, Cohen SD, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL: Psychosocial aspects of chronic disease: ESRD as a paradigmatic illness. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 3042–3055, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Buxo JA, White SA, Himmele R: Frequent hemodialysis: A critical review. Semin Dial 26: 578–589, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganzini L, Goy ER, Dobscha SK: Oregonians’ reasons for requesting physician aid in dying. Arch Intern Med 169: 489–492, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cafazzo JA, Leonard K, Easty AC, Rossos PG, Chan CT: Patient-perceived barriers to the adoption of nocturnal home hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 784–789, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]