Abstract

Purpose

Hyperpolarized (HP) 129Xe gas in the alveoli can be detected separately from 129Xe dissolved in pulmonary barrier tissues (blood plasma and parenchyma) and red blood cells (RBCs) of humans, allowing this isotope to probe impaired gas uptake. Unfortunately, mice, which are favored as lung disease models, do not display a unique RBC resonance, thus limiting the preclinical utility of 129Xe MR. Here we overcome this limitation using a commercially available strain of transgenic mice that exclusively expresses human hemoglobin.

Methods

Dynamic HP 129Xe MR spectroscopy, and 3D radial MRI of gaseous and dissolved 129Xe were performed in both wild type (C57BL/6) and transgenic mice.

Results

Unlike wild type animals, transgenic mice displayed two dissolved 129Xe NMR peaks at 198 and 217 ppm, corresponding to 129Xe dissolved in barrier tissues and RBCs, respectively. Moreover, signal from these resonances could be imaged separately, using a 1-point variant of the Dixon technique.

Conclusion

It is now possible to examine the dynamics and spatial distribution of pulmonary gas uptake by the RBCs of mice using HP 129Xe MR spectroscopy and imaging. When combined with ventilation imaging, this ability will enable translational “mouse-to-human” studies of impaired gas exchange in a variety of pulmonary diseases.

Keywords: hyperpolarized 129Xe, gas exchange, mouse model, red blood cell, interstitial lung disease, chemical shift saturation recovery

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several decades, the mouse has become the most commonly used animal in preclinical studies of pulmonary disorders (1–4). In particular, mouse models have been used extensively to characterize the cellular and molecular events that underlie lung disease and injury. However, to elucidate how these disease mechanisms produce pathological conditions in humans, as well as to determine the degree to which mouse models actually mimic human disease, it is necessary to determine how these cellular and molecular events manifest as pathological changes in pulmonary physiology. To this end, a variety of specialized instruments and techniques have been developed to quantify lung function in mice. For instance, tools to measure respiratory mechanics, such as flexiVent (SCIREQ Scientific Respiratory Equipment Inc. Tempe, AZ), are particularly well developed (5–7). More recently, it has become possible to move beyond global measures of respiratory mechanics in mice and provide regional physiological information by directly visualizing the distribution of pulmonary ventilation, using hyperpolarized (HP) 3He MRI (8,9).

While the ability to visualize pathological changes in ventilation will be invaluable when working with models of obstructive pulmonary disease (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma), additional tools are required to fully assess the range of pathophysiology observed in human disease. In particular, impaired gas exchange is the primary pathological characteristic of a variety of human illnesses, including pneumonitis and interstitial lung disease. Unfortunately, compared to respiratory mechanics, the ability to characterize gas exchange and quantify gas exchange impairment remains relatively underdeveloped. For instance obtaining even the most commonly used clinical measure of gas exchange, the diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), has only recently become possible in mice (10). Moreover, DLCO, like respiratory mechanics, provides only a global measure of lung function. Thus, it is necessary to develop tools that allow the spatial distribution of gas exchange to be observed in mouse models of human disease.

A particularly promising candidate for providing this information is HP 129Xe, which like HP 3He, can be used to visualize ventilation in both humans (11–13) and animals (14–17). However, unlike 3He, 129Xe is soluble in tissues and possesses a large chemical shift range in vivo. In humans inhaled, gaseous 129Xe (typically referenced to 0 ppm) can be detected separately from 129Xe dissolved in the red blood cells (RBCs, 218 ppm) and 129Xe dissolved in the adjacent parenchymal tissues and blood plasma (197 ppm) (18). These properties make 129Xe uniquely suited to probe pulmonary gas exchange, and when deployed in rats, (19,20) have allowed 129Xe spectroscopy to probe impaired gas exchange in a rat model of acute lung injury (21). Subsequently, these properties were exploited to image impaired gas uptake by the red blood cells in a rat model of pulmonary fibrosis. This step was accomplished by employing a 1-point variant of the Dixon MRI technique (22) to separately image the 129Xe uptake in the barrier tissues (lung parenchyma and blood plasma) and RBC compartments (16).

Unfortunately, these properties have been impossible to exploit in mouse models of disease, because mice display only a single dissolved 129Xe resonance at 198 ppm (23) that originates from 129Xe dissolved in both barrier tissues and RBCs. While it is possible to examine the bulk uptake of 129Xe by all pulmonary tissues (i.e., blood and parenchymal tissues combined) in mice (24), the uptake of gas by the red blood cells is of primary physiological interest. Thus, the absence of a distinct RBC peak severely limits the preclinical utility of 129Xe MRI for studying gas exchange.

Here, we demonstrate that this obstacle can be overcome by performing 129Xe MR spectroscopy and imaging in a transgenic strain of mice that exclusively expresses both the α and β subunits of human hemoglobin (25). Further, we found that 129Xe MR data from this transgenic strain display almost identical spectral properties to those observed in humans, and thus provides a far richer level of information about diffusive gas exchange than can be obtained from comparable wild type mice. Additionally, we show that it is possible to obtain high-resolution, 3D images of ventilation from these same animals, thus allowing a wide range of physiological information to be extracted from mice using a single contrast agent.

METHODS

Animal Preparation

Wild type (C57BL/6, n = 3, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and transgenic mice (B6;129-Hbatm1(HBA)Tow Hbbtm2(HBG1,HBB*)Tow/Hbbtm3(HBG1,HBB)Tow/J, n = 3 Jackson Laboratory) were prepared following procedures approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. It should be noted that the transgenic strain was originally developed as a model of sickle cell disease. However, only non-sickling animals that were homozygous for normal, rather than sickle cell, human hemoglobin were used in this work.

Prior to MR experiments, animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 75-mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, Lundbeck, Inc., Deerfield, IL), and intubated by tracheostomy with an 18-G catheter (Abbocath, Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) to provide an airtight seal for mechanical ventilation. Anesthesia was maintained with periodic injections of sodium pentobarbital (25 mg/kg) administered via a 22-G IP catheter. Animals were ventilated (75% N2 and 25% O2) at a rate of 100 breaths/minute on an HP-gas compatible, constant-volume, mechanical ventilator (26) using a tidal volume of 0.20 ml. During 129Xe MR acquisition, HP 129Xe replaced the N2 in the breathing gas mixture, while holding the O2 concentration constant. During MR acquisitions, the ventilation rate was reduced to 75 breaths/minute (140-ms inhalation period, a 360-ms breath-hold, and a 300-ms period of passive exhalation) to accommodate a longer mechanical breath-hold.

While in the MR magnet, the body temperature of the mice was monitored via a rectal thermistor and maintained at ~35°C by warm air flowing through the magnet bore. Airway pressure was monitored by a pressure transducer attached to the ventilator gas delivery lines near the trachea of the mouse. Heart rate was monitored via electrocardiogram readings using custom LabVIEW 8.1 software (National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX, USA). This software also controlled the timing of the ventila and triggered the MR acquisition. Following imaging, mice were euthanized by injection of sodium pentobarbitol overdose.

HP 129Xe Production and Delivery

Both natural abundance (26% 129Xe) or isotopically enriched (85% 129Xe) xenon was hyperpolarized in a 1% Xe, 10% N2, 89% He mixture (Linde Electronics and Specialty Gases Inc., Stewartsville, NJ), by spin exchange optical pumping using a prototype commercial polarizer (model 9800, MITI, Durham, NC) and extracted from the buffer gases in a liquid nitrogen trap (27). Following cryogenic accumulation, HP 129Xe (polarization ~10%) was thawed into 150-mL Tedlar bags (Jensen Inert Products, Coral Springs, FL) housed inside a Plexiglas cylinder. This cylinder was then pressurized to 3.5 psig, and HP 129Xe was delivered to the mice using the custom ventilator, as described previously (26).

MR Spectroscopy

All 129Xe MR spectra were acquired from natural abundance xenon at 2.0 T using a horizontal, 30-cm bore magnet (Oxford Instruments, Oxford, UK) equipped with 180-mT/m shielded gradients and a GE Excite 12.0 console (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). This console was interfaced with a dual-resonance 129Xe/1H (23.66/85.54 MHz), 4-cm long, quadrature birdcage coil (m2m Imaging, Cleveland, OH) and operated at 23.66/85.54 MHz instead of its intrinsic frequency (63.86 MHz) using a frequency up-down converter (Cummings Electronics Labs, North Andover, MA).

Prior to data acquisition, the mouse was briefly ventilated with HP 129Xe, and spectroscopy was performed to determine the resonance frequencies of the dissolved and gaseous 129Xe peaks, set the RF flip angle, and perform in vivo shimming. Preliminary spectroscopy was also used to determine the nominal echo time (TE) required for the RBC and barrier tissue resonances to accumulate the 90° phase difference (TE90) needed to perform 1-point Dixon imaging of 129Xe uptake (16).

To examine the global dissolved 129Xe replenishment dynamics, 129Xe spectra were acquired from the whole lung after applying 90° RF pulses to the dissolved phase peaks at repetition times (TRs) ranging from 20 to 200 ms (14 TRs in total). The RF pulse consisted of a 3-lobe, 1000 µs sinc pulse with 4-kHz excitation bandwidth, which primarily excited the dissolved phase but also applied a flip angle of ~1° to the gas-phase resonance. All spectra were acquired with gating over the course of multiple breath-holds (TE = 1132 µs, BW = 15.625 kHz, and 512 points per FID). For each mouse, one set of spectra was acquired during the breath-hold and one set was acquired at end expiration. To construct the dynamic signal intensity build-up curves, a varying number of acquisitions were averaged (51–201 frames) to yield sufficient signal intensity for data fitting, while limiting the total acquisition time per spectrum to ~30 s, and the first FID obtained from each breath was discarded before processing and averaging with matNMR (28). The intensities of the dissolved peaks were determined by Gaussian deconvolution in MATLAB R2011b (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). Intensities of the narrower gas-phase excitations were determined using a Lorentzian fit.

Signal Dynamics

The signal dynamics of both dissolved HP 129Xe signal peaks were fit to a slightly modified version of a recently published model of xenon exchange, MOXE (29). Previous efforts to model 129Xe uptake by the gas exchange tissues either: 1) accounted for diffusive uptake by the RBC and barrier tissues, but assumed a static “slab” of tissues (16); or 2) accounted for continued accumulation of dissolved 129Xe signal due to blood flow, but did not incorporate the spectral information available from the two dissolved 129Xe peaks (30). In contrast, the MOXE model expresses time-dependent signals from barrier peak, Sbarrier, and RBC peak, SRBC, as

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

In Eqs. 1 and 2, TR is the repetition time, δ is the barrier thickness, d is the septal thickness. The parameter η is the fraction of xenon dissolved in the RBCs relative to total xenon dissolved in the blood, which is given by

| (3) |

where Hct is the blood hematocrit, and λRBC and λplasma are the solubility of xenon in the red blood cells and blood plasma, respectively. Literature values for these constants appear in Table 1. Additionally, the fitting parameters used in the model are the Xe-exchange time constant, tEx; pulmonary-capillary transit time, tTx; and scaling parameters bRBC and bbarrier. It should be noted that the original MOXE model used a single scaling parameter b, whereas two scaling parameters were used here to allow the formulae to fit data with varying RBC/barrier ratios.

Table 1.

Physiological constants for modeling xenon exchange.

| Constant | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| δ, barrier thickness | 0.57 µm | Mercer, 1994 (42) |

| d, septal thickness | 1.51 µm | Mei, 2007 (43) |

| Hct, hematocrit | 0.42 | Ryan, 1997 (25) |

| λRBCa, Xe solubility in RBCs | 0.2710 | Chen, 1980 (44) |

| λPlasmaa, Xe solubility in plasma | 0.0939 | Chen, 1980 (44) |

| η | 0.711 | Eq. 3 |

Ostwald solubilities were obtained from canine blood.

In the 3 transgenic animals, a total of 6 TR-dependent buildup curves were acquired (2 curves each mouse). Signal intensites from each time point were then averaged across all 6 datasets and divided by their corresponding gas phase signals. Finally, both RBC and barrier datasets were simultaneously fit to Eqs. 1 and 2 using a steepest descent gradient-fitting routine and the shared set of fitting parameters. The errors calculated for each data point are the residuals (root mean square difference) between the Gaussian fits and the acquired spectra, combined across data sets using standard error propagation. The 95% confidence intervals of the fit were determined based on the X2 goodness-of-fit. Data from the 3 wild type animals (2 curves each), which displayed a single resonance, were averaged and fit to the sum of Eqs. 1 and 2. To reduce the chance that the steepest descent algorithm converged on a local rather than global minimum, the algorithm was run 1000 times from randomly generated vectors with starting values (tEx: 0.01–0.11 s, tTx: 0.2–0.7 s, with bRBC and bbarrier scaling randomly between 0 and 200% of the maximum intensity for each resonance).

Imaging

All 129Xe MR images were acquired from isotopically enriched xenon. Ventilation imaging used a 3D radial sequence (views = 2501, views per breath = 4, TR = 10 ms, flip angle = 30°, matrix = 64×64×64, FOV = 2.0 cm, acquisition BW = 8 kHz), which employed a non-selective, 500-µs, 3-lobe sinc pulse with 8-kHz excitation bandwidth. While this 500-µs pulse provided non-negligible off-resonance excitation of the dissolved-phase pool, the resulting dissolved-phase 129Xe signal was insignificant relative to the gaseous signal originating from the 100-fold larger alveolar magnetization pool. Dissolved 129Xe image acquisition used the same 3D radial sequence, but employed a 1200-µs, 3-lobe sinc pulse (excitation BW = 3 kHz) to selectively excite dissolved 129Xe. This pulse caused a ~0.1° flip to be applied to the gas phase, which did not materially affect image quality owing to a minimal effect on the source gas-phase magnetization pool. Additional dissolved 129Xe acquisition parameters included: radial views = 1073, views per breath = 6, TR = 50 ms, TE = 858 µs, flip angle = 90°, matrix = 32×32×32, number of excitations (NEX) = 16, FOV = 2 cm, and BW = 15.625 kHz. Note, the dissolved 129Xe images were acquired with a longer TR, relative to ventilation images, to permit diffusive replenishment of the dissolved magnetization from the alveolar spaces. Ventilation images benefit further from a reduction in TR in terms of reduced T1 relaxation, and reduced motional blurring.

For transgenic mice exhibiting both barrier (parenchymal tissue and blood plasma) and RBC resonances, dissolved-phase images were acquired using the 1-point Dixon technique (22). For this acquisition, both the excitation and receiver frequencies were set on resonance with the RBC peak, such that the barrier peak lagged in phase behind the RBC peak as the transverse magnetization evolved following excitation. Image acquisition was timed such that the phase difference between the two peaks reached 90° when imaging encoding was initiated. The nominal TE at which this phase separation occurred was empirically determined to be 858 µs using whole-lung 129Xe spectroscopy (31).

RESULTS

HP 129Xe Spectroscopy

Consistent with previous observations (23), spectra obtained from the lungs of wild type mice exhibited a single NMR resonance at 198 ppm (Fig. 1A and 1B) that originated from 129Xe dissolved in the pulmonary tissues, including the RBCs. Although a second peak appeared at 194 ppm when sufficiently long repetition times (TR > 1 s) were used (see Fig. 1C), this spectral feature can be attributed to 129Xe dissolved in extrapulmonary fatty tissues (20). When the same experiment was performed using a transgenic mouse strain, in which the wild type mouse hemoglobin (both α and β subunits) was knocked out and replaced by human hemoglobin, the NMR spectra displayed two dissolved peaks at 198 and 217 ppm (see Fig. 1D), which are almost identical to the frequencies observed in humans. The 129Xe spectrum from these transgenic animals also displayed a third peak at 194 ppm (Fig. 1E), which appeared at long TRs (> 1 s), indicating that, like the similar peak observed from wild type animals, it arose from extrapulmonary fat tissues.

Figure 1.

HP 129Xe spectroscopy in mice with 20-Hz line broadening. (A) Spectrum from a wild type (C57/BL6) mouse at TR = 360ms and NEX = 101 referenced to gas-phase 129Xe at 0 ppm. (B) Close-up of the same dissolved phase peak from a wild type mouse, showing only one peak. (C) Dissolved-phase region of the spectrum at TR = 8 s and NEX = 75, showing, a second peak associated with 129Xe dissolved in fat outside the lung. (D) Dissolved 129Xe spectrum at TR = 360 ms and NEX = 201 from a transgenic mouse, showing two peaks—one associated with the plasma and parenchymal tissues and one with red blood cells. (E) Spectrum from the same transgenic animal as shown in 1D, at TR = 8 s and NEX = 75, showing the emergence of a third, fat-associated peak.

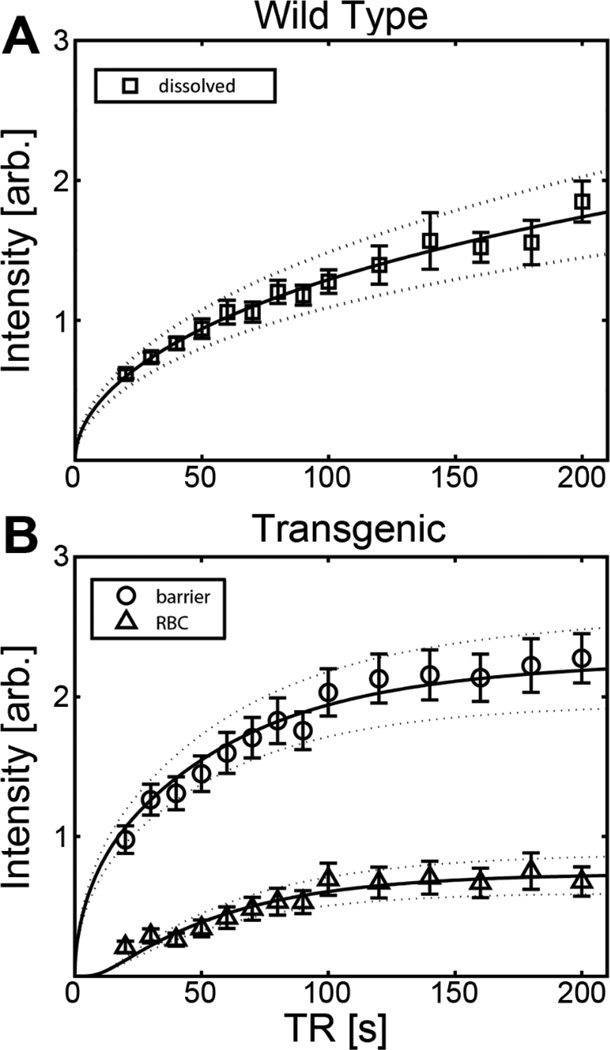

HP 129Xe Signal Dynamics

For wild type mice, the 129Xe dynamic, signal build-up curve (32) (see Fig. 2A) was characterized by relatively rapid signal increase up to a saturation time of ~100 ms, followed by gradual increase from signal in the distal, extrapulmonary tissues. When the data were fit for both the xenon exchange time and the pulmonary-capillary transit time, values of tEx = 300 ± 20 ms and tTx = 460 ± 20 ms were obtained. This value for tTx is plausibly close to the previously published value for the pulmonary-capillary transit time of 830 ms, found using synchrotron radiation angiography (33). However, the value for tEx is unphysiologically long. In contrast, the additional spectral information provided by the transgenic animals allowed signal recovery data from both the barrier tissues and RBCs (Fig. 2B) to be analyzed, and the resulting fit yielded reasonable, population-averaged values of tEx = 56 ± 6 ms and tTx = 610 ± 60 ms—both of which are physiologically realistic.

Figure 2.

HP 129Xe signal dynamics in mice fit to the MOXE model of 129Xe uptake (solid lines). Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals. (A) Signal build-up curve for wild type mice (average of all 3). (B) Signal build-up curve for the transgenic mice (average of all 3) showing time-dependent HP 129Xe accumulation by both the RBC and barrier tissues.

Imaging

Ventilation images acquired in this work (see Fig. 3) were obtained with a 3D, isotropic resolution of 312 µm and a relatively high parenchymal SNR of 21. The combination of resolution and SNR allowed structural features to be visualized that were not observable in previously published 2D, HP 129Xe images of mouse lungs (34). For instance, the first two generations of the airways can be seen and are clearly delineated from 129Xe in the more distal lung parenchyma. Also visible in the image is signal intensity void corresponding to the expected anatomical location of the vena cava.

Figure 3.

129Xe ventilation imaging with an isotropic resolution of 312 µm in the transgenic mouse, showing regions of high signal intensity in the first two generations of airways (thin arrows), as well as regions of lower intensity in the region corresponding to the anatomical location of the vena cava (thick arrow).

Similar structural features can also be observed in dissolved 129Xe images obtained from a wild type mouse (see Fig. 4) with an isotropic 625-µm resolution and an SNR of 12. That is, circular dark spots are observed in regions corresponding to the locations of the larger airways seen in the ventilation images, where no gas exchange occurs. Additionally, the signal intensity of this image displays a reasonably high coefficient of variation (CV) of 0.20, indicating that there is significant regional heterogeneity in gas uptake, even in this normal, healthy animal. Interestingly, several circular bright spots can also be seen in the image. Although the source of these bright spots has not been investigated, they may correspond to regions of increased gas uptake or tissue density. Alternatively, it is possible that at TR = 50 ms, there was sufficient time in these regions for magnetization to wash away from the gas-exchange tissues, and that the bright spots thus correspond to dissolved 129Xe signal arising from the larger vasculature.

Figure 4.

MR imaging of dissolved 129Xe in mice. Dissolved 129Xe image from a wild type mouse, displaying regions of lower intensity corresponding to the larger airways (left column). Dissolved 129Xe imaging in the transgenic mouse (two columns on right). In one slice, the locations of several larger airways are indicated by thin arrows. A region of higher intensity is indicated by a thick arrow. By employing 1-point Dixon imaging it is possible to separate the dissolved 129Xe signal into separate images, depicting gas uptake by the barrier tissue and red blood cells.

Dissolved 129Xe images with the same 625-µm isotropic resolution were also acquired from a transgenic animal (see right two columns of Fig. 4). However, by selecting the appropriate echo time (858 µs), the resulting data could be separated into images resulting from 129Xe gas uptake by the barrier tissues and RBCs. The barrier image was obtained with an SNR of 32 and a CV of 0.23, while the RBC image has an SNR of 22 and a CV of 0.25. These SNR values are in reasonable proportion to the fraction of the dissolved 129Xe spectrum attributable to both fractions. (Note, the higher dissolved-phase SNR observed from the transgenic compared to the wild type animal resulted from greater signal averaging, NEX=16 versus NEX = 8, and possibly varying polarization levels).

DISCUSSION

HP 129Xe Spectroscopy in Mice

The appearance of a single dissolved 129Xe resonance from the barrier tissues and RBCs observed in wild type mice, a pattern which incidentally is also observed in rabbits (35), stands in stark contrast to spectra observed from most other species studied to date—including humans (13,18,36), rats (21,37), dogs (38), sheep (39), and pigs (40)—that display distinct barrier tissue- and RBC-specific peaks. Although the exact mechanism that causes this spectral difference remains unknown, it is well established that the RBC-specific peaks result from 129Xe interactions with hemoglobin within the RBCs (41). Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the absence of RBC-specific peaks in mice result from differing xenon-hemoglobin binding interactions relative to other species. Indeed, we have now demonstrated that this speculation is correct by showing that transgenic mice expressing human hemoglobin generate two dissolved 129Xe peaks, which occur at almost identical frequencies to the barrier (197 ppm) and RBC peaks (218 ppm) seen in human subjects (18,36). Moreover, the ability to separately detect the RBC and barrier components of the gas-exchange tissues potentially provides a means of extracting more accurate and useful physiological information in mice.

For instance, curve fitting of our data from the wild type mice did not yield physiologically reasonable values for the exchange time. More specifically, the resulting estimate of the pulmonary-capillary transit time (460 ms) was reasonable, but the xenon exchange time was unphysiologically long. In contrast, having the ability to fit the barrier and RBC signal recovery data together (Fig. 2B) permitted both the exchange and capillary transit time to be determined, and the result for the capillary transit time of 610 ms was in reasonable agreement with the value of 830 ± 30 ms (33) previously published.

It should be noted that Imai, et al. (24) demonstrated that physiologically sensible parameters could be extracted from dissolved-phase signal dynamics in wild type mice, and Patz, et al. (30) demonstrated that sensible results could also be obtained from humans at 0.2 T, where the two dissolved 129Xe resonances are collapsed into a single peak. Both of these earlier studies utilized a conventional chemical shift saturation recovery (CSSR) sequence that employed a saturation-excitation RF pair separated by a variable signal replenishment delay time. In wild type mice (24), sensible values were likely obtained, because the CSSR sequence permitted the use of signal replenishment times as short as 1.4 ms, which enabled the relatively rapid signal dynamics present in mice to be probed in sufficient detail. In the low-field human work, replenishment times did not extend below 20 ms, but this was likely sufficiently short to capture the slower physiology present in human subjects. Thus, in future work, it may be possible to extract even more robust and accurate physiological information from these transgenic mice using a CSSR approach.

Interestingly, while the two dissolved 129Xe peaks observed in the transgenic mice display spectral frequencies similar to those observed in humans, the linewidths of these peaks were quite broad. That is, both peaks displayed linewidths of 11 ppm, which exceeded by more than 200% the 5-ppm linewidths observed from the single peak seen in wild type mice. These broad lines cannot be trivially attributed to poor shimming, because gas-phase line widths obtained from whole-lung spectroscopy did not noticeably vary between wild type and transgenic mice. Additionally, the width of these resonances did not increase at longer TR, indicating blood flow to other, more distal tissues did not cause the observed spectral broadening. Interestingly, the dissolved 129Xe linewidths from the transgenic mice are also approximately 40% broader than those observed from rats, using identical MR equipment and spectral processing techniques (31). It should be noted that although the hemoglobin has been altered in these transgenic mice, they still retain their native cell structure, which is likely different from humans and rats. Taken together, these observations suggest that the broadening observed in the transgenic mice likely resulted from more rapid diffusive 129Xe exchange between the mouse erythrocytes and the adjacent spectral compartments.

Imaging Lung Function

Previous images of HP 129Xe in the mouse lung have been limited to 2D and displayed a relatively low, 1.25 mm × 0.8 mm in-plane resolution (34), which was insufficient to distinguish finer anatomical details. The superior SNR and image quality displayed by our images (Fig. 3) was made possible by acquiring image data during multiple inspiratory breaths, using a highly reproducible, hyperpolarized 129Xe compatable, mechanical ventilator (26). Indeed, using a similar ventilation and imaging strategy, we were also able to generate sufficiently high signal intensity to image 129Xe dissolved in the pulmonary tissues. Furthermore, applying 1-point Dixon imaging to dissolved-phase 129Xe in the transgenic animal enabled the visualization of 129Xe transfer into the barrier and RBC compartments separately. In this case, the images illustrate the normal function expected in a healthy mouse. That is, 129Xe signal is observed from the RBCs wherever there is also uptake by the barrier tissues. However, regional mismatching (i.e., reduced RBC signal relative to barrier tissue signal) is expected when diffusive gas exchange is impaired, for instance as a result of barrier tissue thickening caused by pulmonary fibrosis (16,31).

CONCLUSION

Using a transgenic strain that expresses human hemoglobin, it is now possible to probe diffusive gas exchange between the alveolar spaces and the red blood cells using both dynamic 129Xe spectroscopy and 3D isotropic imaging. This new capability will significantly enhance the utility of 129Xe MRI in mouse models of interstitial lung disease. Further, when combined with quantitative (11) ventilation imaging, these methods make possible translational “mouse-to-human” studies of impaired gas exchange in a variety of pulmonary diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by NHLBI R01HL105643 and NHLBI 1K99-HL-111217-01A1 and performed at the Duke Center for In Vivo Microscopy, a National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIH/NIBIB) National Biomedical Technology Resource Center (NIBIB P41 EB015897). The authors also wish to thank Dr. Thomas C. O'Haver (University of Maryland, College Park, MD) for providing code useful for the deconvolution of spectral peaks, Sally Zimney for carefully reading the manuscript, and Dr. Laurence Hedlund for valuable discussions regarding the development of this experiment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baron RM, Choi AJS, Owen CA, Choi AMK. Genetically manipulated mouse models of lung disease: potential and pitfalls. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302(6):L485–L497. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00085.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson DJ, Dorin JR, McLachlan G, Ranaldi V, Lamb D, Doherty C, Govan J, Porteous DJ. Lung-Disease in the Cystic-Fibrosis Mouse Exposed to Bacterial Pathogens. Nat Genet. 1995;9(4):351–357. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keith RC, Powers JL, Redente EF, Sergew A, Martin RJ, Gizinski A, Holers VM, Sakaguchi S, Riches DWH. A novel model of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease in SKG mice. Exp Lung Res. 2012;38(2):55–66. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2011.636139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kung AL. Practices and Pitfalls of Mouse Cancer Models in Drug Discovery. In: Garret M, Hampton KSGFVW, George K, editors. Adv Cancer Res. Volume 96. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 191–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang K, Mitzner W, Rabold R, Schofield B, Lee H, Biswal S, Tankersley CG. Variation in senescent-dependent lung changes in inbred mouse strains. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(4):1632–1639. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00833.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang K, Rabold R, Schofield B, Mitzner W, Tankersley CG. Age-dependent changes of airway and lung parenchyma in C57BL/6J mice. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(1):200–206. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00400.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates JH, Irvin CG, Farré R, Hantos Z. Oscillation mechanics of the respiratory system. Comprehensive Physiology. 2011;1:1233–1272. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mistry N, Thomas AC, Kaushik SS, Johnson GA, Driehuys B. Quantitative analysis of hyperpolarized 3He ventilation changes in mice challenged with methacholine. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(3):658–666. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas AC, Nouls JC, Driehuys B, Voltz JW, Fubara B, Foley J, Bradbury JA, Zeldin DC. Ventilation defects observed with hyperpolarized 3He magnetic resonance imaging in a mouse model of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44(5):648. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0287OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallica J, Das S, Horton M, Mitzner W. Application of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity in the mouse lung. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110(5):1455–1459. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01347.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virgincar RS, Cleveland ZI, Kaushik SS, Freeman MS, Nouls J, Cofer GP, Martinez-Jimenez S, He M, Kraft M, Wolber J, McAdams HP, Driehuys B. Quantitative analysis of hyperpolarized 129Xe ventilation imaging in healthy volunteers and subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(4):424–435. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirby M, Svenningsen S, Owrangi A, Wheatley A, Farag A, Ouriadov A, Santyr GE, Etemad-Rezai R, Coxson HO, McCormack DG, Parraga G. Hyperpolarized 3He and 129Xe MR Imaging in Healthy Volunteers and Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Radiology. 2012;265(2):600–610. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mugler JP, Altes TA, Ruset IC, Dregely IM, Mata JF, Miller GW, Ketel S, Ketel J, Hersman FW, Ruppert K. Simultaneous magnetic resonance imaging of ventilation distribution and gas uptake in the human lung using hyperpolarized 129Xe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(50):21707–21712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011912107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleveland ZI, Möller HE, Hedlund LW, Nouls JC, Freeman MS, Qi Y, Driehuys B. In Vivo MR Imaging of Pulmonary Perfusion and Gas Exchange in Rats via Continuous Extracorporeal Infusion of Hyperpolarized 129Xe. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Driehuys B, Moller HE, Cleveland ZI, Pollaro J, Hedlund LW. Pulmonary Perfusion and Xenon Gas Exchange in Rats: MR Imaging with Intravenous Injection of Hyperpolarized 129Xe. Radiology. 2009;252(2):386–393. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522081550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driehuys B, Cofer GP, Pollaro J, Boslego J, Hedlund LW, Johnson GA. Imaging alveolar capillary gas transfer using hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(48):18278–18283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608458103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couch MJ, Ouriadov A, Santyr GE. Regional ventilation mapping of the rat lung using hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(5):1623–1631. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mugler JP, Driehuys B, Brookeman JR, Cates GD, Berr SS, Bryant RG, Daniel TM, deLange EE, Downs JH, Erickson CJ, Happer W, Hinton DP, Kassel NF, Maier T, Phillips CD, Saam BT, Sauer KL, Wagshul ME. MR imaging and spectroscopy using hyperpolarized 129Xe gas: Preliminary human results. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(6):809–815. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakai K, Bilek AM, Oteiza E, Walsworth RL, Balamore D, Jolesz FA, Albert MS. Temporal dynamics of hyperpolarized 129Xe resonances in living rats. J Magn Reson B. 1996;111(3):300–304. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swanson SD, Rosen MS, Coulter KP, Welsh RC, Chupp TE. Distribution and dynamics of laser-polarized 129Xe magnetization in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42(6):1137–1145. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1137::aid-mrm19>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansson S, Wolber J, Driehuys B, Wollmer P, Golman K. Characterization of diffusing capacity and perfusion of the rat lung in a lipopolysaccaride disease model using hyperpolarized 129Xe. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(6):1170–1179. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J. Dixon techniques for water and fat imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(3):543–558. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagshul ME, Button TM, Li HFF, Liang ZR, Springer CS, Zhong K, Wishnia A. In vivo MR imaging and spectroscopy using hyperpolarized 129Xe. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(2):183–191. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imai H, Kimura A, Iguchi S, Hori Y, Masuda S, Fujiwara H. Noninvasive detection of pulmonary tissue destruction in a mouse model of emphysema using hyperpolarized 129Xe MRS under spontaneous respiration. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(4):929–938. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan TM, Ciavatta DJ, Townes TM. Knockout-transgenic mouse model of sickle cell disease. Science. 1997;278(5339):873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nouls J, Fanarjian M, Hedlund L, Driehuys B. A Constant-Volume Ventilator and Gas Recapture System for Hyperpolarized Gas MRI of Mouse and Rat Lungs. Concept Magn Reson B. 2011;39B(2):78–88. doi: 10.1002/cmr.b.20192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Driehuys B, Cates GD, Miron E, Sauer K, Walter DK, Happer W. High-volume production of laser-polarized 129Xe. Appl Phys Lett. 1996;69(12):1668–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Beek JD. matNMR: A flexible toolbox for processing, analyzing and visualizing magnetic resonance data in Matlab®. J Magn Reson. 2007;187(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang YLV. MOXE: A model of gas exchange for hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance of the lung. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(3):884–890. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patz S, Muradyan I, Hrovat MI, Dabaghyan M, Washko GR, Hatabu H, Butler JP. Diffusion of hyperpolarized 129Xe in the lung: a simplified model of 129Xe septal uptake and experimental results. New J Phys. 2011;13(1):015009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleveland ZI, Qi Y, Driehuys B. Imaging Impaired Gas Uptake in a Rat Model of Pulmonary Fibrosis with 3D Hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. 2013. abstract #1454. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butler JP, Mair RW, Hoffmann D, Hrovat MI, Rogers RA, Topulos GP, Walsworth RL, Patz S. Measuring surface-area-to-volume ratios in soft porous materials using laser-polarized xenon interphase exchange nuclear magnetic resonance. J Phys-Condens Mat. 2002;14(13):L297–L304. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/14/13/103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonobe T, Schwenke DO, Pearson JT, Yoshimoto M, Fujii Y, Umetani K, Shirai M. Imaging of the closed-chest mouse pulmonary circulation using synchrotron radiation microangiography. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(1):75–80. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00205.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imai H, Kimura A, Hori Y, Iguchi S, Kitao T, Okubo E, Ito T, Matsuzaki T, Fujiwara H. Hyperpolarized 129Xe lung MRI in spontaneously breathing mice with respiratory gated fast imaging and its application to pulmonary functional imaging. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(10):1343–1352. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang Y, Mata J, Cai J, Altes T, Brookeman J, Hagspiel K, Mugler J, III, Ruppert K. Detection of a new pulmonary gas-exchange component for hyperpolarized 129Xe. Proc ISMRM. 2008;16:201. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleveland ZI, Cofer GP, Metz G, Beaver D, Nouls J, Kaushik SS, Kraft M, Wolber J, Kelly KT, McAdams HP, Driehuys B. Hyperpolarized 129Xe MR Imaging of Alveolar Gas Uptake in Humans. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Driehuys B, Pollaro J, Cofer GP. In vivo MRI using real-time production of hyperpolarized 129Xe. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(1):14–20. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruppert K, Brookeman JR, Hagspiel KD, Mugler JP. Probing lung physiology with xenon polarization transfer contrast (XTC) Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(3):349–357. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200009)44:3<349::aid-mrm2>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawata Y, Kamiya T, Miura H, Kimura A, Fujiwara H. Practical application of NMR spectra of 129Xe dissolved in red blood cell. Elsevier; 2004. pp. 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amor N, Hamilton K, Küppers M, Steinseifer U, Appelt S, Blümich B, Schmitz-Rode T. NMR and MRI of Blood-Dissolved Hyperpolarized 129Xe in Different Hollow-Fiber Membranes. ChemPhysChem. 2011;12(16):2941–2947. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolber J, Cherubini A, Leach MO, Bifone A. Hyperpolarized 129Xe NMR as a probe for blood oxygenation. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43(4):491–496. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200004)43:4<491::aid-mrm1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mercer RR, Russell ML, Crapo J. Alveolar septal structure in different species. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77(3):1060–1066. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.3.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mei SH, McCarter SD, Deng Y, Parker CH, Liles WC, Stewart DJ. Prevention of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiopoietin 1. PLoS medicine. 2007;4(9):e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen R, Fan F, Kim S, Jan K, Usami S, Chien S. Tissue-blood partition coefficient for xenon: temperature and hematocrit dependence. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49(2):178–183. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]