Abstract

Purpose of review

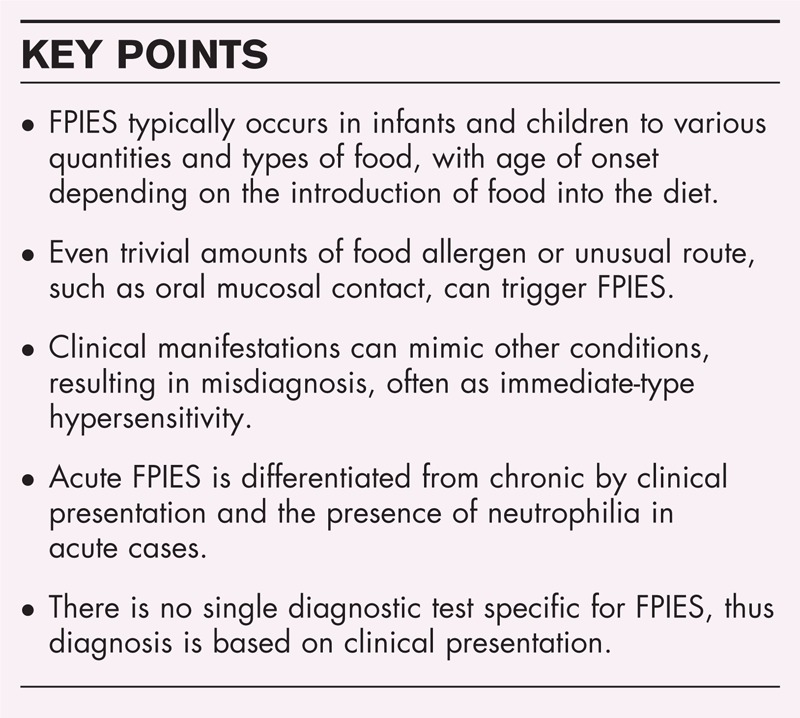

To raise awareness among healthcare providers about the clinical and laboratory findings in acute and chronic food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES).

Recent findings

FPIES can be caused by trivial exposure or rare foods.

Summary

FPIES is a non-IgE-mediated reaction that usually presents with acute severe repetitive vomiting and diarrhea associated with lethargy, pallor, dehydration, and even hypovolemic shock. Manifestations resolve usually within 24–48 h of elimination of the causative food. In chronic cases, symptoms may include persistent diarrhea, poor weight gain, failure to thrive, and improvement may take several days after the food elimination. In the acute cases, laboratory evaluation may reveal thrombocytosis and neutrophilia, peaking about 6 h postingestion. Depending on the severity, metabolic acidosis and methemoglobinemia may occur. In chronic cases, anemia, hypoalbuminemia and eosinophilia may be seen. Radiologic evaluation or other procedures, such as endoscopy and gastric juice analysis may show nonspecific abnormal findings. The diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations. Further studies looking at the phenotypes of FPIES are needed to identify clinical subtypes, and to understand the predisposing factors for developing FPIES compared with immediate-type, IgE-mediated gastroenteropathies.

Keywords: food allergy, food anaphylaxis, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, rice allergy

INTRODUCTION

Food-protein induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) is a non-IgE-mediated reaction affecting predominantly infants and children. Adult cases have been recently reported but are rare [1▪]. A majority of cases occur during infancy, particularly with the early introduction of additional foods. With the general recommendation of delaying introduction of solid foods until 4–6 months, solid-food FPIES presents later than when caused by cow's milk or soybean formulas.

FPIES is characterized by an abnormal response to an ingested food resulting in gastrointestinal inflammation and increased intestinal mucosal permeability [2]. Although sensitization is a prerequisite, some cases apparently occurred following the first exposure that might indicate that the initial sensitizing exposure can be trivial [3,4]. The amount of food required to provoke symptoms has varied widely, reflecting the degree of hypersensitivity in individual patients. The threshold dose could be a normal serving size or a very minute quantity. Although the route of exposure is primarily ingestion, in some patients oral mucosal contact can be significant [5▪▪].

The clinical presentation of FPIES is primarily vomiting and diarrhea, which can be acute or chronic. Comparisons of clinical findings in selected studies are shown in Table 1[6–12]. This review will focus on the clinical and laboratory findings in FPIES. The key features in acute and chronic FPIES are shown in Table 2[2,13].

Table 1.

Clinical manifestations of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome according to selected studies published from 2003 to 2013

| Study/author | Study duration | No. of patients | No. of FPIES episodes | Onset of vomiting | Signs and symptoms | Laboratory findings |

| Nowak et al. [6] | 5 yr | 14 | 42 | <10 min–3 h; avg 2 h | Vomiting 95%, diarrhea 47%, lethargy 40%, melena 11% hypotension 7% | Increased polymorphonuclear cells; range 700–15000 cells/mm3, median increase 4500 cells/mm3 |

| Hwang et al. [7] | 3 yr | 16 | N/A | N/A | Poor weight gain <10 g/day | Hypoalbuminemia; range 3.3–4.2 g/dl, avg <3.6 g/dl; eosinophiia; range 100–520 cells/mm3; thrombocytosis; range 424–844 × 103/μl; methemoglobinemia 18% |

| Hwang et al. [8] | 5 yr | 23 | 27 | 1 h–4 h; avg 2 h | Vomiting 100%, diarrhea 33%, lethargy 100%, hypotension 11%, cyanosis 22% | Methemoglobinemia 13% |

| Mehr et al. [9] | 16 yr | 35 | 66 | 20 min–6 h; avg 1.8 h | Vomiting 100%, diarrhea 24%, lethargy 84%, pallor 66%, hypothermia 24% | Neutrophilia; range 370–16500 cells/mm3, avg 10100 cells/mm3; thrombocytosis (>500 × 103/ml) 63% |

| Katz et al. [10] | 2 yr | 44 | 28 | 30 min–3 h; avg 2 h | Vomiting 100%, diarrhea 25%, lethargy 77%, pallor 14%, melena 4.5% | N/A |

| Sopo et al. [11] | 7 yr | 66 | 165 | 30 min–4 h; avg 2 h | Vomiting 98%, diarrhea 54%, pallor 80%, hypotension 77% | N/A |

| Ruffner et al. [12] | 5 yr | N/A | 462 | 2–6 h | Vomiting alone 45.3%, vomiting and diarrhea 54.7%, lethargy/pallor/hypotension/ cyanosis/dehydration 5.1% | N/A |

FPIES, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome; yr, year.

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory findings in acute versus chronic food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome

| Features | Acute | Chronic |

| Vomiting | Acute repetitive, projectile | Intermittent |

| Diarrhea | Acute, +/− blood | Chronic, +/− blood |

| Other clinical findings | Severe symptoms, hypothermia, pallor, lethargy and shock | Mild symptoms, weight loss, failure to thrive |

| Hematologic | Thrombocytosis, neutrophilia | Anemia, eosinophilia |

| Other laboratory tests | Metabolic acidosis, methemoglobinemia, elevated gastric juice lymphocytes | Hypoalbuminemia, metabolic acidosis, methemoglobinemia, stool reducing substances |

Box 1.

no caption available

ACUTE FOOD-PROTEIN INDUCED ENTEROCOLITIS SYNDROME

The first episode of FPIES usually occurs suddenly and progresses rapidly in an alarming manner. Symptoms occur when the causative food is ingested intermittently, which often facilitates identification of the offending food. The typical course of an acute event is persistent projectile vomiting, pallor, followed by diarrhea that can lead to lethargy and dehydration. Resolution of symptoms usually occurs within 24–48 h. The patient appears normal between exposures and returns to baseline once the offending food is eliminated.

Vomiting is by far the most prominent symptom, being reported in more than 95% of the cases [6,8–12,14▪▪]. It usually occurs 0.5–6 h postingestion (average 2 h) and is characterized by frequent projectile episodes, every 10–15 min, and can reach more than 20 episodes in some cases [2]. Lethargy and pallor have been reported in 40–100% of cases [6,8–11]. However, in a retrospective study [12] based on review of medical records, out of 462 pediatric cases, only 5% were documented to have lethargy and pallor. Loose or watery diarrhea occurs in 20–50% of patients, usually about 6 h after ingestion of the causative food, but can be more delayed up to 16 h [2,8]. Bloody diarrhea has been reported in 4–11% of cases [6,8–11], but as high as 45% in one study [14▪▪].

Very severe symptoms can occur, ranging from 5 to 24% of cases, as intractable protracted vomiting, lethargy, pallor, hypotension, dehydration, and hypothermia with temperature less than 36° [6,8,9,11–13]. Such a presentation is often misdiagnosed as IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. Recovery occurs with prompt management, primarily by intravenous fluids, though complete clinical resolution may take 2–3 days. Acute symptoms recur on exposure to the causative food.

Selected cases

We [5▪▪] encountered an infant who had three acute FPIES episodes: the first was at 5 months of age, the symptoms occurred 30 min after chewing on a cellophane wrapper; the second was after ingestion of a tablespoon of pureed sweet potato; and the third was after a few sips of rice cereal mixed with breast milk. It was realized that in the first episode, the wrapper was covering a rice cake. This case was peculiar in that it occurred in an exclusively breastfed infant and by noningestant oral contact with a trivial quantity of rice allergen.

Although milk and some other common foods are the most implicated, some cases have been caused by less allergenic foods. Recently, an infant was reported of having multiple episodes of FPIES to boiled egg yolk, which is known to be much less allergenic than egg white [15]. However, contamination with the traces of egg white protein could not be ruled out.

We recently saw an 11-month-old female infant with a history of eczema who was exclusively breastfed until 6 weeks of age. Excessive fussiness, irritability, and intermittent diarrhea with blood and mucus were reported few days after supplementation with cow's milk formula. She continued to have symptoms after switching to soybean formula. At 4 months, feeding extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (Nutramigen, Mead Johnson) resulted in marked improvement in eczema and gastrointestinal symptoms. By 6 months of age, rice cereal, pureed mixed vegetables, and fruits were tolerated. One month later, the patient began to have intermittent episodes of vomiting and diarrhea with blood and mucus. All solid foods were eliminated from the infant's diet for 3 weeks and symptoms resolved. Although exclusively on Nutramigen, the infant ate 1/4 cup of cooked steamed rice and after 30 min developed explosive vomiting and lethargy. All solid foods were eliminated and symptoms resolved within 1–2 days. An upper gastrointestinal series showed significant gastroesophageal reflux, and endoscopy showed healthy mucosa with normal biopsy findings. Because of poor weight gain, caloric intake was increased and the patient was switched to amino acid formula (Neocate, Nutricia). During our evaluation, the medical history revealed rice and green peas as the most suspected and were eliminated. Skin prick testing was significantly positive to cow's milk, egg white, egg yolk, and peanut, but negative to green peas. Total IgE was 16 IU/ml and specific IgE to egg white was 4.12 KU/l (class 3). We recommended strict elimination trial of cow's milk, egg, and peanut as a probable cause of eczema. This case emphasizes a couple of points. First, FPIES can present with mild, chronic symptoms that can resolve with the feeding of a hypoallergenic formula. Second, in FPIES patients with associated atopy, positive allergy tests (skin prick or specific IgE) are more likely relevant to the atopic disease rather than to FPIES.

CHRONIC FPIES

In mild to moderate cases, daily or frequent exposure to the causative food leads to chronic symptoms, characterized by intermittent vomiting, abdominal distention, chronic diarrhea that may contain mucus or blood, irritability, failure to thrive, and poor weight gain (<10 g/day in infants) [7]. The most commonly implicated causes of chronic FPIES in infants and young children are cow's milk and soybean milk. Once the offending food is identified and eliminated from the diet, symptoms improve within days. Acute episodes occur upon re-exposure to the causative food, and can be severe if the ingested quantity is substantial.

LABORATORY FINDINGS

The diagnosis of FPIES is basically clinical and is being addressed in detail in another article in this publication. Allergy testing, specific IgE and skin prick testing are negative in more than 90% of patients. The clinical manifestations of FPIES are usually associated with laboratory abnormalities depending on the severity and duration of symptoms.

Blood tests

Acute symptoms are usually associated with neutrophilia [6,9,16], peaking 6 h after ingestion of the causative food, with an increase by 5500–16 800 cells/mm3 (mean increase 9900 cells/mm3) [17]. Thrombocytosis (platelet count >500 × 103/ml; range: 375–637 × 103 cells/ml) has been reported in more than 60% of acute cases [9]. Chronic FPIES is associated with lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, and often anemia, probably secondary to malnutrition [7,13]. In a series of 16 infants with chronic cow's milk FPIES, hypoalbuminemia with a serum albumin level below 3.0 g/dl was reported in 100% of patients [7]. Both acute and chronic FPIES can be associated with various degrees of lymphocytosis and metabolic acidosis. Intestinal mucosal inflammation may be severe enough and causes reduction of catalase activity, and may lead to increased nitrite, resulting in methemoglobinemia that has been reported in 13–18% of acute cases [7,8,18,19]. Typically, laboratory findings normalize and clinical improvement is seen within 48 h of avoiding the causative food.

Stool analysis

Depending on the severity and/or duration of symptoms, the stool may contain visible or occult blood, Charcoat–Leyden crystals, reducing substances, increased carbohydrate content, leukocytes, and eosinophils [13,20].

Radiologic imaging

Abdominal roenterograms can show abnormal findings depending on the severity of symptoms, for example, increased bowel loops, intramural gas, distended small bowel, jejunal wall thickening [9,21,22]. These findings may mimic gastrointestinal obstruction or necrotizing enterocolitis in young infants.

Gastric lavage and endoscopy

Gastric juice analysis was performed in a series of 16 infants with cow's milk FPIES; 15 revealed more than 10 leukocytes per high powered field reflecting inflammation [23]. Endoscopy can show a friable colonic mucosa with rectal ulcerations and bleeding. Varying degrees of villous atrophy, tissue edema, and crypt abscesses may be seen. Histopathology reveals increased lymphocytes, increased eosinophils, and increased mast cells [22].

CONCLUSION

The presentation of FPIES varies depending on whether symptoms are acute or chronic. Acute FPIES is differentiated from chronic FPIES in that it presents with severe vomiting, diarrhea, lethargy, thrombocytosis, neutrophilia, and occasionally methemoglobinemia. Once the offending food is avoided, clinical resolution occurs with 2–3 days. In chronic cases, patients may present with mild intermittent vomiting and diarrhea, failure to thrive, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and eosinophilia, and clinical resolution may take longer time. Stool analysis, radiologic imaging, gastric juice analysis, and endoscopy can show abnormalities, but findings are generally nonspecific and are not part of routine diagnostic evaluation of FPIES. The diagnosis is primarily on clinical basis. Early recognition of FPIES and elimination of the causative food are crucial in preventing recurrence and facilitation of complete resolution.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1▪.Fernandes BN, Boyle RJ, Gore C, et al. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome can occur in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130:1199–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This seems to be the first case report of FPIES in adults.

- 2.Jarvinin K, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES): current management strategies and review of the literature. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 1:317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan J, Campbell D, Mehr S. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in an exclusively breast-fed infant-an uncommon entity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monti G, Castagno E, Liguori SA, et al. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome by cow's milk proteins passed through breast milk. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:679–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5▪▪.Mane SK, Hollister ME, Bahna SL. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome to trivial oral mucosal contact. Eur J Pediatr 2013; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report describes a severe FPIES to trivial exposure: chewing a wrapper of rice cake.

- 6.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome caused by solid food proteins. Pediatrics 2003; 111:829–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang JB, Lee SH, Kang YN, et al. Indexes of suspicion of typical cow milk protein-induced enterocolitis. J Korean Med Sci 2007; 22:993–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang JB, Sohn SM, Kim AS. Prospective follow-up oral food challenge in food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Arch Dis Child 2009; 94:425–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehr S, Kakakios A, Frith K, et al. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: 16-year experience. Pediatrics 2009; 123:459–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz Y, Goldberg MR, Rajuan N, et al. The prevalence and natural course of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome to cow milk: a large-scale, prospective population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:647–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sopo SM, Giorgio V, Dello Iacono I, et al. A multicentre retrospective study of 66 Italian children with food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: different management for different phenotypes. Clin Exp Allergy 2012; 42:1257–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruffner M, Ruymann K, Barni S, et al. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: insights from review of a large referral population. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 1:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard SA, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Manifestations, diagnosis, and management of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Pediatr Ann 2013; 42:135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14▪▪.Nomura I, Morita H, Ohya Y, et al. Non–IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies: distinct differences in clinical phenotype between Western countries and Japan. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2012; 12:297–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study revealed a higher frequency of FPIES with bloody diarrhea in Japan compared with Western countries.

- 15.Arik Y, Cavkaytar O, Uysal S, et al. Egg yolk: an unusual trigger of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2013; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sicherer SH, Eigenmann PA, Sampson HA. Clinical features of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. J Pediatr 1998; 133:214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell GK. Milk- and soy-induced enterocolitis of infancy: clinical features and standardization of challenge. J Pediatr 1978; 93:553–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand RK, Appachi E. Case report of methemoglobinemia in two patients with food protein-induced enterocolitis. Clin Pediatr 2006; 45:679–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sicherer SH. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: clinical perspectives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000; 30:s45–s49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caubet JC, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Current understanding of the immune mechanisms of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2011; 7:317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayasooriya S, Fox A, Murch S. Do not laparotomize food-protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007; 23:173–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Muraro A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 9:371–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang JB, Song JY, Kang YN, et al. The significance of gastric juice analysis for a positive challenge by a standard oral challenge test in typical cow milk protein-induced enterocolitis. J Korean Med Sci 2008; 23:251–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]