Abstract

Research suggests that prenatal testosterone exposure may masculinize (i.e., lower) disordered eating (DE) attitudes and behaviors and influence the lower prevalence of eating disorders in males versus females. How or when these effects become prominent remains unknown, although puberty may be a critical developmental period. In animals, the masculinizing effects of early testosterone exposure become expressed during puberty when gonadal hormones activate sex-typical behaviors, including eating behaviors. This study examined whether the masculinizing effects of prenatal testosterone exposure on DE attitudes emerge during puberty in 394 twins from opposite-sex and same-sex pairs. Twin type (opposite sex vs. same sex) was used as a proxy for level of prenatal testosterone exposure because females from opposite-sex twin pairs are thought to be exposed to testosterone in utero from their male co-twin. Consistent with animal data, there were no differences in levels of DE attitudes between opposite-sex and same-sex twins during pre-early puberty. However, during mid-late puberty, females from opposite-sex twin pairs (i.e., females with a male co-twin) exhibited more masculinized (i.e., lower) DE attitudes than females from same-sex twin pairs (i.e., females with a female co-twin), independent of several “third variables” (e.g., body mass index [BMI], anxiety). Findings suggest that prenatal testosterone exposure may decrease DE attitudes and at least partially underlie sex differences in risk for DE attitudes after mid-puberty.

Keywords: disordered eating, eating disorder, puberty, sex difference, testosterone

Sex differences in eating disorder prevalence are pronounced, with the female-to-male ratio estimated to be 3:1 to 10:1 (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007). Sex disparities are often attributed to sociocultural factors (e.g., pressures for thinness) that may preferentially increase risk for eating disorders in females; however, gonadal hormones are promising biological candidates (Klump et al., 2006). Perinatal (i.e., prenatal and neonatal periods) testosterone exposure exerts organizational (e.g., permanent) effects. That masculinize (i.e., to make male-like) the brain, physiology, and behavior (Breedlove, 1994), and the degree of masculinization reflects the level of testosterone exposure. For example, female rodents positioned next to males in utero are exposed to elevated levels of testosterone and subsequently show masculinized characteristics, such as more aggression relative to females that developed adjacent to other females (see Ryan & Vandenbergh, 2002). Similarly, female rats that are exogenously administered testosterone during peri-natal development display masculinized (i.e., elevated) food intake relative to female controls (Donohoe & Stevens, 1983; Madrid, Lopez-Bote, & Martin, 1993).

Researchers have begun to model similar masculinization effects for disordered eating (DE) attitudes and behaviors1 in humans, using indirect assessments of early testosterone exposure (e.g., digit ratios [index finger (2D)/ring finger (4D)] and opposite-sex twin pairs). Digit ratios are sexually dimorphic (i.e., lower 2D:4D in males as early as 9 weeks gestation; Malas, Dogan, Evcil, & Desdicioglu, 2006) biomarkers of prenatal testosterone exposure (Breedlove, 2010), and opposite-sex twin pairs offer information on prenatal exposure through comparisons of females from opposite-sex twin pairs (herein referred to as females with a male co-twin, denoted “Fm”) to control females (i.e., same-sex female twins and/or singletons). Because Fm twins are thought to be exposed to testosterone prenatally from their male co-twin (Miller, 1994), they should be more masculinized on traits and disorders than control females, similar to the intrauterine position effects observed in rodents.

As would be predicted from animal studies, more masculinized (i.e., lower) 2D:4D ratios are associated with lower levels of DE attitudes and behaviors (e.g., body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, dietary restraint, binge eating) in young adult males (Smith, Hawkeswood, & Joiner, 2010) and females (Klump et al., 2006). With some exceptions (Baker, Lichtenstein, & Kendler, 2009; Lydecker et al., 2012), young adult Fm twins also exhibit masculinized (i.e., lower) levels of DE attitudes and behaviors (e.g., body dissatisfaction, weight preoccupation, binge eating, compensatory behaviors, dietary restraint; Culbert, Breedlove, Burt, & Klump, 2008; Culbert et al., 2010) than females from same-sex twin pairs (i.e., herein referred to as females with a female co-twin, denoted “Ff”). Trends toward lower levels of intentional weight loss (odds ratio = 0.78, p = .06) and rates of broad anorexia nervosa (odds ratio = 0.65, p = .10) have also been found in Fm twins relative to Ff twins (Raevuori et al., 2008). Critically, in humans, masculinization could be due to socialization from the male, same-aged co-twin; however, Fm twins exhibit lower levels of DE attitudes and behaviors than nontwin females reared with a close-in-age brother (Culbert et al., 2008, 2010), suggesting that socialization is unlikely to account for results. These findings are corroborated by data showing that Fm twins are masculinized on several physical traits unaffected by socialization (e.g., fewer spontaneous otoacoustic emissions; McFadden, 1993).

Taken together, animal data indicate that perinatal testosterone exposure masculinizes feeding behavior, a key phenotype disrupted in eating disorders, and human studies suggest that prenatal testosterone exposure masculinizes several DE attitudes and behaviors. These data highlight perinatal testosterone exposure as a potential biological mechanism underlying sex differences in risk for eating disorders in adulthood. However, it is currently unknown when prenatal testosterone’s masculinizing effects on DE attitudes and behaviors emerge. Identifying when these effects become prominent may provide further insight into how prenatal testosterone influences risk for eating disorders.

Puberty may be a key developmental period. Perinatal testosterone influences the later expression of many sex-differentiated behaviors by programming activational (i.e., effects that influence neural systems and behavior transiently) and sex-specific responses to gonadal hormones after puberty. Lower levels of early testosterone exposure (typical of females) enable the brain to respond to ovarian hormones after puberty, whereas higher levels (typical of males) decrease sensitivity to ovarian hormones (Bell & Zucker, 1971; Gentry & Wade, 1976). For example, in rodents, sex differences in food intake emerge during and after puberty (Wade, 1972). Female rats treated with testosterone during perinatal development also begin to show male-like (i.e., increased) food intake during and after puberty (Bell & Zucker, 1971), and critically, exogenous administration of ovarian hormones in adulthood does not reverse this male-like eating behavior (Donohoe & Stevens, 1983; Gentry & Wade, 1976; Zucker, 1969), suggesting permanent masculinization.

To date, no study has investigated whether prenatal testosterone’s masculinizing effects on DE attitudes and/or behaviors become expressed during puberty, but indirect lines of evidence support this possibility. First, sex differences in rates of DE attitudes and behaviors become prominent during adolescence and appear to be relatively minimal before puberty (i.e., during childhood; Ferreiro, Seoane, & Senra, 2011). Second, DE attitudes and behaviors are associated with the activational effects of ovarian hormones after pubertal onset. Changes in estradiol and progesterone predict changes in binge eating, emotional eating, weight preoccupation, and body dissatisfaction across the menstrual cycle, independent of changes in body weight or negative affect (Edler, Lipson, & Keel, 2007; Klump, Keel, Culbert, & Edler, 2008; Klump et al., 2013; Racine et al., 2012), suggesting direct associations between circulating ovarian hormones and DE phenotypes in adulthood. These direct influences confirm that DE attitudes and behaviors are responsive to circulating ovarian hormones, a critical piece of evidence for establishing that the emergence of sex differences in risk for DE attitudes and behaviors during puberty could result from differential sensitivity to ovarian hormones due to differential prenatal testosterone exposure. Studies that examine rates of DE attitudes and behaviors across puberty and utilize measures of prenatal testosterone exposure (e.g., Fm twins vs. other twin types) are needed to confirm that pubertal changes in sex-differentiated risk reflect prenatal testosterone effects.

The current study investigated this possibility by examining a sample of male and female twins from same-sex and opposite-sex twin pairs during puberty. We assessed a broad range of DE variables (e.g., body dissatisfaction, weight preoccupation, eating concerns, dietary restraint) that (a) are core features of eating disorders (e.g., anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa), (b) prospectively predict the later development of clinical pathology (Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwaan, Kraemer, & Stewart, 2004), and (c) are linked to the organizational and/or activational effects of gonadal hormones (e.g., Culbert et al., 2008; Edler et al., 2007; Klump et al., 2008; Klump et al., 2013; Racine et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2010). We hypothesized that pubertal status would moderate the effects of prenatal testosterone on DE variables, such that there would be no sex (i.e., male vs. female) or twin-type (i.e., opposite-sex vs. same-sex twins) differences in DE variables during pre-early puberty. In contrast, we expected significant differences in DE variables across sex and twin type during mid-late puberty, such that DE levels would be lowest in males, intermediate in Fm twins, and highest in Ff twins. All analyses controlled for socialization effects from being reared with a male co-twin by including a group of nontwin females who were raised with a brother. Several developmental (i.e., autonomy difficulties) and sex-moderated factors (i.e., body mass index [BMI], anxiety and depression symptoms) were included as covariates to isolate prenatal testosterone exposure as the most likely factor contributing to the emergence of sex differentiated risk during puberty.

Method

Participants

Participants were 394 male and female twins from same-sex and opposite-sex twin pairs (see Table 1 for sample sizes) from the population-based Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR; see Burt & Klump, in press; Klump & Burt, 2006). The MSUTR recruits twins across lower Michigan through birth records via the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH; for descriptions of recruitment methods, see Burt & Klump, in press; Klump & Burt, 2006). Briefly, the MDCH mailed recruitment packets to twin pairs who met age criteria and whose addresses could be located via parent drivers’ license information. Identical procedures were used to recruit 63 nontwin females reared with at least one biological brother within 1 to 4 years of their age. Response rates (~50%) were similar across twin and nontwin samples and on par with those of other population-based twin registries (e.g., Kendler, Heath, Neale, Kessler, & Eaves, 1992). Consistent with the recruitment region2 and other MSUTR studies (Culbert et al., 2008), participant ethnic/racial backgrounds varied (e.g., Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, Native American Asian/Pacific Rim, other/multiracial), but the majority of participants were Caucasian (~84%) and largely of mid- to upper-level (~69%) socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1975).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Pre-Early pubertal group

|

Mid-Late pubertal group

|

Full sample

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Fm | Ff | NT | Males | Fm | Ff | NT | Males | Fm | Ff | NT | |

| Sample size (n) | 112 | 29–30 | 72–74 | 18–19 | 40 | 34 | 103–104 | 42–44 | 152 | 63–64 | 175–178 | 60–63 |

| Mean age (SD) | 12.06 (1.36) | 11.73 (1.09) | 11.44 (0.94) | 12.12 (1.29) | 13.96 (1.30) | 14.03 (1.45) | 13.23 (1.16) | 13.72 (1.37) | 12.56 (1.58) | 12.95 (1.73) | 12.49 (1.39) | 13.24 (1.53) |

| Raw MEBS scores | ||||||||||||

| Total score | ||||||||||||

| Range (maximum = 30) | 0–19 | 0–18 | 0–17 | 0–11 | 0–17 | 0–18 | 0–24 | 1–21 | 0–19 | 0–18 | 0–24 | 0–21 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.47 (4.60) | 4.07 (4.74) | 4.72 (4.17) | 4.44 (3.05) | 4.03 (4.36) | 5.82 (4.88) | 7.74 (6.02) | 8.06 (5.98) | 4.36 (4.52) | 5.00 (4.86) | 6.48 (5.52) | 6.97 (5.51) |

| % above MEBS clinical cutoff | 4.46 | 3.33 | 4.05 | 0.00 | 2.50 | 2.94 | 12.50 | 11.90 | 3.95 | 3.13 | 8.99 | 8.33 |

| Body dissatisfaction | ||||||||||||

| Range (maximum = 6) | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–5 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–6 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.79 (1.44) | 0.80 (1.49) | 0.86 (1.28) | 0.72 (1.18) | 0.80 (1.34) | 1.41 (1.84) | 1.94 (2.06) | 2.05 (1.96) | 0.79 (1.41) | 1.13 (1.70) | 1.50 (1.85) | 1.65 (1.86) |

| Weight preoccupation | ||||||||||||

| Range (maximum = 8) | 0–7 | 0–6 | 0–7 | 0–5 | 0–7 | 0–7 | 0–8 | 0–8 | 0–7 | 0–7 | 0–8 | 0–8 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.62 (1.83) | 1.63 (1.88) | 1.89 (1.85) | 2.06 (1.39) | 1.28 (1.76) | 2.00 (1.91) | 3.09 (2.39) | 3.14 (2.40) | 1.53 (1.81) | 1.83 (1.89) | 2.59 (2.25) | 2.82 (2.19) |

| Raw EDE-Q scores | ||||||||||||

| Total score | ||||||||||||

| Range (maximum = 6) | 0–4.26 | 0–3.39 | 0–3.0 | 0–3.74 | 0–2.22 | 0–3.22 | 0–4.74 | 0–4.48 | 0–4.26 | 0–3.39 | 0–4.74 | 0–4.48 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.65 (0.84) | 0.65 (0.98) | 0.65 (0.73) | 0.68 (0.86) | 0.57 (0.60) | 0.96 (0.85) | 1.37 (1.22) | 1.37 (1.23) | 0.63 (0.79) | 0.81 (0.92) | 1.07 (1.10) | 1.16 (1.17) |

| Shape concerns | ||||||||||||

| Range (maximum = 6) | 0–5.13 | 0–4.0 | 0–3.88 | 0–5.0 | 0–3.5 | 0–4.88 | 0–5.25 | 0–6.0 | 0–5.13 | 0–4.88 | 0–5.25 | 0–6.0 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.77 (1.10) | 0.84 (1.24) | 0.83 (1.02) | 0.91 (1.16) | 0.77 (0.90) | 1.37 (1.26) | 1.87 (1.56) | 1.88 (1.63) | 0.77 (1.05) | 1.13 (1.27) | 1.45 (1.46) | 1.59 (1.56) |

| Weight concerns | ||||||||||||

| Range (maximum = 6) | 0–5.2 | 0–3.6 | 0–3.4 | 0–4.4 | 0–3.8 | 0–5.0 | 0–6.0 | 0–5.8 | 0–5.2 | 0–5.0 | 0–6.0 | 0–5.8 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.72 (1.01) | 0.74 (1.11) | 0.82 (0.96) | 0.80 (1.05) | 0.63 (0.85) | 1.09 (1.20) | 1.57 (1.55) | 1.60 (1.54) | 0.70 (0.97) | 0.93 (1.17) | 1.26 (1.40) | 1.36 (1.45) |

Note. Mean scores = raw values, i.e., not adjusted for any covariate (e.g., age, body mass index). EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, MEBS = Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey. Ff = females with a female co-twin, Fm = female with a male co-twin, NT = nontwin females. SD = standard deviation.

Measures

Disordered eating variables

DE variables were assessed with two well validated measures: the Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (MEBS) and the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE–Q). The use of both measures allowed us to examine the replicability of findings and possible unique effects for each scale. Previous studies that found masculinized DE attitudes and behaviors in Fm twins used the MEBS (Culbert et al., 2008), so our use of both measures ensures that results are not questionnaire specific. As expected, correlations between the MEBS and EDE-Q subscales were moderate to high in males (mean r = .71; range = .62 to .81) and females (mean r = .75; range = .71 to .80).

MEBS

The MEBS3 (von Ranson, Klump, Iacono, & McGue, 2005), which was designed for use in children as young as 9 years old, assesses a range of DE attitudes and behaviors. Subscales include body dissatisfaction (dissatisfaction with one’s body size/ shape), weight preoccupation (preoccupation with dieting, weight, and the pursuit of thinness), binge eating (thinking about and/or engaging in binge eating), and compensatory behaviors (using or contemplate using compensatory behaviors, e.g., self-induced vomiting). A total score is calculated by summing all items. Higher scores indicate higher levels of DE pathology.

Consistent with previous studies that examined pre- to early adolescents (e.g., Klump, Keel, Sisk, & Burt, 2010), the MEBS total score, body dissatisfaction, and weight preoccupation scales were included in analyses. These scales demonstrated good internal consistency (αs = .71 to .89 across sex and pubertal groups) and expected associations with external correlates, including depressive symptoms (using the Children’s Depression Inventory [CDI]; mean r = .47; ps <.05), anxiety symptoms (using the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; mean r = .29; ps < .05), and BMI (mean r = .37; ps <.05), in males and females. These scales have previously demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, including good 3-year stability (mean rs: total score = .67; body dissatisfaction = .63; weight preoccupation = .58; von Ranson et al., 2005), and a replicable factor structure in pre- to early adolescent male and female samples (Marderosian et al., personal communication, July 7, 2011; von Ranson et al., 2005). The MEBS has also been shown to successfully discriminate between individuals with eating disorders versus controls (von Ranson et al., 2005).

Binge eating and compensatory behavior subscales were not examined due to their low internal consistency (αs < .65) in key sample groups (e.g., males) and a general low endorsement of compensatory behaviors (i.e., within subgroups, 90 to 100% of participants denied the use of any compensatory behavior). These psychometric issues are not surprising because these subscales tend to be less internally consistent in pre- to early adolescent samples (e.g., Klump et al., 2010, 2012; von Ranson et al., 2005) and show lower 3-year stability (rs = .21 to .32; von Ranson et al., 2005) relative to the other MEBS scales. Although the binge eating and compensatory subscales could not be examined separately in analyses, items from the binge eating and compensatory behaviors subscales were retained in the MEBS total score to remain consistent with prior work (e.g., Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2010, 2012) and standard scoring procedures (von Ranson et al., 2005). Thus, the MEBS total score includes items spanning DE attitudes and behaviors. Nonetheless, the total score most likely represents DE attitudes in this study of preadolescent/adolescent male and female twins, given the lower endorsement of behavior-based items (e.g., binge eating and compensatory behaviors) and the fact that the MEBS total score was more highly correlated with the attitude based subscales (i.e., body dissatisfaction, weight preoccupation; males mean r = .80; females mean r = .85) than the binge eating and compensatory behavior subscales (males mean r = .59; females mean r = .60).

EDE-Q

The EDE-Q (Fairburn & Bèglin, 1994) assesses several DE attitudes and behaviors, including shape concerns (dissatisfaction with one’s body shape), weight concerns (preoccupation with weight and a desire to lose weight), eating concerns (preoccupation with food, eating in secret, and guilt about eating), and dietary restraint (restraint over eating and avoidance of eating). A total score is comprised of items across all subscales. Higher scores indicate higher levels of DE pathology. The EDE-Q has demonstrated good psychometric properties in males and females (Carter, Stewart, & Fairburn, 2001; Lavender, De Young, & Anderson, 2010), including high correlations with the EDE interview and good 1-year stability (e.g., total score, r = .79; shape concerns, r = .75; weight concerns, r = .73; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen, & Beaumont, 2004). Notably, the factor structure of the EDE/EDE-Q has been less stable in community-based samples, resulting in recommendations to focus on the total score and/or weight/shape concern items (e.g., Byrne, Allen, Lampard, Dove, & Fursland, 2010; Wade, Byrne, & Bryant-Waugh, 2008). The EDE-Q total score, shape concerns, and weight concerns scales were therefore examined in analyses. These three scales showed good internal consistency in the current study (αs = .73 to .94 across sex and all pubertal groups) and expected associations with depressive symptoms (mean r = .47; ps <.05), anxiety symptoms (mean r = .33; ps < .05), and BMI (mean r = .36; ps <.05) in males and females. The EDE-Q dietary restraint and eating concerns subscales exhibited unacceptable internal consistency (αs = .50 to .62) in some sample groups (e.g., males, Fm twins) in our and previous (e.g., Decaluwé & Braet, 2004) pre- to early adolescent samples and were therefore not examined separately in analyses. Nonetheless, all attitudinal and behavioral items were retained in the EDE-Q total score to remain consistent with standard scoring procedures (Fairburn & Bèglin, 1994). Like the MEBS total score, the EDEQ total score likely reflects mainly DE attitudes, particularly body shape and weight concerns, as these subscales showed higher correlations (males mean r = .93; females mean r = .96) with the EDE-Q total score than the more behavioral eating concerns and dietary restraint scales (males, r = .77; females, r = .80). The term “DE attitudes” is used herein to describe the DE variables examined in this study.

Pubertal Status

Pubertal status was determined from the self-report Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988), which assessed height spurts, body hair, and skin changes in males and females, breast development and menses in females, and voice changes in males. Onset of menses was rated as present or absent. Other items were rated on a 4-point continuous scale ranging from development has not yet begun to development seems completed. Previous research has demonstrated good psychometric properties for the PDS in males and females (Petersen et al., 1988), and categorical classifications correlate highly (r ~.70) with clinician ratings of pubertal development (Petersen et al., 1988). Internal consistency on the PDS was good for males (α = .86) and females (α = .81) in this sample.

Participants were categorized as pre-early puberty (PDS score ≤2.4) or mid-late puberty (PDS score ≥2.5) from average PDS scores (see Table 1 for sample sizes4). This two-group approach was used because (1) previous studies of puberty’s hormone effects on DE variables have used this approach and shown substantial increases in phenotypic and genetic effects on DE at mid-puberty (e.g., Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2007, 2012), and (b) small sample sizes in some groups (e.g., Fm twins and nontwin females) prohibited us from examining more than two categories.

Covariates

Age and ethnicity were covaried, given previous associations with DE attitudes (Croll, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Ireland, 2002; Ferreiro et al., 2011). BMI, anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms were covaried because they are risk factors for eating disorders (Jacobi et al., 2004) that change during puberty (Hayward & Sanborn, 2002), differ between sexes (females > males; e.g., Ferreiro et al., 2011; Hayward & Sanborn, 2002), and are associated with gonadal hormones (e.g., Angold, Costello, Erkanli, & Worthman, 1999; Schulz, Molenda-Figueira, & Sisk, 2009). BMI was calculated (Weight [in kilograms]/Height [in meters] squared) using a wall-mounted ruler and digital scale measurements. Anxiety was measured with the total score (e.g., physical symptoms, separation/panic, social anxiety, and harm avoidance) from the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997). Depression was assessed with the total score (e.g., anhedonia, negative mood, and self-esteem) from the CDI (Kovacs, 1985). The CDI and MASC total scores showed good internal consistency (CDI: αs = .82–.88; MASC: αs = .79–.90) and have demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in other adolescent samples (Kovacs, 1985; March et al., 1997).

Autonomy difficulties were covaried, given theories postulating that girls develop DE attitudes during puberty to avoid maturation and the necessary separation from attachment figures (Eggert, 2007; Marsden, Meyer, Fuller, & Waller, 2002). Notably, Ff twins might experience greater autonomy difficulties than Fm twins or female nontwins, as Ff twins would need to separate from a same-sex co-twin in addition to a same-sex parent (Klump, 1996). Autonomy difficulties (e.g., fears of developing autonomy from an important person) were examined using the Separation Anxiety subscale of the Separation-Individuation Test of Adolescence (SITA; Levine, Green, & Millon, 1986). Higher scores indicate greater autonomy difficulties. On par with previous reports (Eggert, 2007; Levine et al., 1986), Cronbach’s alpha for the Separation Anxiety sub-scale was .66 to .77 across sex and pubertal groups.

Statistical Analyses

Data preparation

Subscale scores were prorated for participants missing ≤10% of items and coded as missing for participants (n = 4 to 6) missing >10% of items. Ethnicity was dummy coded to represent four ethnic/racial categories (Hispanic, Caucasian, Black, and, due to small sample sizes, an “other” category of Native American, Asian/Pacific Rim, or Multiracial), with Caucasian coded as the reference group. Males from same-sex (i.e., Mm) and opposite-sex (i.e., Mf) twin pairs were combined into one “male” group because preliminary analyses indicated no significant differences on DE attitudes (ps = .30 to .95; Cohen’s d = .01 to .15). The lack of mean differences between Mm and Mf twins is consistent with some (e.g., Baker et al., 2009), but not all (e.g., Culbert et al., 2008), previous research.

Sex differences and prenatal testosterone effects across puberty

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) examined whether the masculinizing effects of prenatal testosterone become prominent during mid-late puberty, such that sex and twin type (e.g., Fm twins vs. other twin types) differences in DE attitudes would only be present in the mid-late pubertal group. GLMM was an ideal statistical method because the nonindependence of twin dyads could be accounted for by nesting the lower-level unit (i.e., individual twin) within an upper-level unit (i.e., twin pair). Data transformations (to account for small to moderate positive skew of dependent variables, i.e., skewness = 0.42 to 2.34 across subgroups) could also be incorporated directly into GLMMs, which eliminated the need to transform dependent variables prior to analyses and allowed model estimates to remain on their original measurement scale. GLMMs were fit using normal distribution with square-root (i.e., MEBS body dissatisfaction and all EDE-Q scales) or log-link (i.e., MEBS total and weight preoccupation scales) functions, as these models provided the best fit to these data.5

Each GLMM examined one dependent variable (e.g., MEBS total score or EDE-Q total score) and the following predictors: twin type (males, Fm twins, Ff twins, nontwin females), pubertal status (pre-early puberty or mid-late puberty), twin type × pubertal status interaction, and six covariates (i.e., age, ethnicity, BMI, autonomy difficulties, depression, and anxiety). GLMMs were also conducted without covariates to ensure that their inclusion did not unduly bias results (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011).

The “twin type” models were selected over the Actor–Partner Interdependence models (twin’s sex/co-twins’s sex) used in previous reports (i.e., Culbert et al., 2008), as twin type models provided all pairwise comparisons and allowed for the inclusion of the nontwin female group. Sex was not included as a predictor because sex is embedded within the twin-type variable (see previous discussion), and we did not necessarily expect a main effect of sex; we expected levels of DE attitudes to vary across females depending on whether the female twin was in utero with a male co-twin (i.e., Fm twins) or not (i.e., Ff twins and nontwin females). Thus, instead of including sex as an independent variable, we examined sex differences in DE attitudes using pairwise comparisons. We expected significant twin type × pubertal status interactions, such that between-groups differences in DE attitudes would vary by pubertal status (i.e., no sex or twin-type differences in pre-early puberty; significant sex and twin type differences in mid-late puberty). To examine sex (i.e., male twins vs. Ff twins and nontwins) and twin-type (i.e., Fm twins vs. other groups) differences within each pubertal group, pairwise comparisons were specified within our interaction models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

All participant groups exhibited a range of DE attitudes across the spectrum of severity (see Table 1). A total of 6.39% of participants scored above the clinical cutoff for the MEBS total score (score = 15.55; von Ranson et al., 2005), but as expected, the percentage was larger in mid-late puberty (9.13%) than pre-early puberty (3.78%), particularly for Ff twins and nontwins (see Table 1).

Sex Differences and Prenatal Testosterone Effects Across Puberty

GLMM results confirmed hypothesized sex and twin-type differences only after mid-puberty for all DE variables. Twin type × pubertal status interactions were significant (or approached significance) across DE attitude scales, and results were nearly identical across models with and without covariates (see Table 2).

Table 2.

GLMMs Examining Twin Type by Pubertal Status Interactions

| Raw models

|

Covariate models

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(df, df) | p | F(df, df) | p | |

| Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey

|

||||

| Total score | ||||

| Twin Type | 2.11 (3, 446) | <.10 | 2.47 (3, 423) | .06 |

| Puberty | 7.99 (1, 446) | .005 | 2.80 (1, 423) | <.10 |

| Twin Type × Puberty | 2.25 (3, 446) | .08 | 2.87 (3, 423) | .04 |

| Body dissatisfaction | ||||

| Twin Type | 2.10 (3, 443) | .10 | 3.63 (3, 421) | .01 |

| Puberty | 11.56 (1, 443) | .001 | 0.90 (1, 421) | .34 |

| Twin Type × Puberty | 2.06 (3, 443) | .10 | 4.24 (3, 421) | .006 |

| Weight preoccupation | ||||

| Twin Type | 5.32 (3, 446) | .001 | 4.03 (3, 424) | .008 |

| Puberty | 4.97 (1, 446) | .03 | 0.62 (1, 424) | .43 |

| Twin Type × Puberty | 2.99 (3, 446) | .03 | 2.29 (3, 424) | .08 |

| Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire

|

||||

| Total score | ||||

| Twin Type | 3.03 (3, 448) | .03 | 4.42 (3, 425) | .004 |

| Puberty | 10.31 (1, 448) | .001 | 0.76 (1, 425) | .38 |

| Twin Type × Puberty | 3.56 (3, 448) | .01 | 3.89 (3, 425) | .009 |

| Shape concerns | ||||

| Twin Type | 3.74 (3, 446) | .01 | 5.34 (3, 423) | .001 |

| Puberty | 13.11 (1, 446) | .001 | 0.80 (1, 423) | .37 |

| Twin Type × Puberty | 3.20 (3, 446) | .02 | 3.60 (3, 423) | .01 |

| Weight concerns | ||||

| Twin Type | 3.24 (3, 446) | .02 | 4.01 (3, 423) | .008 |

| Puberty | 7.77 (1, 446) | .006 | 1.24 (1, 423) | .27 |

| Twin Type × Puberty | 2.61 (3, 446) | .05 | 2.51 (3, 423) | .06 |

Note. Raw models were not adjusted for any covariate. Covariate models were adjusted for age, ethnicity, body mass index, autonomy difficulties, and depression and anxiety symptoms. GLMM = generalized linear mixed models.

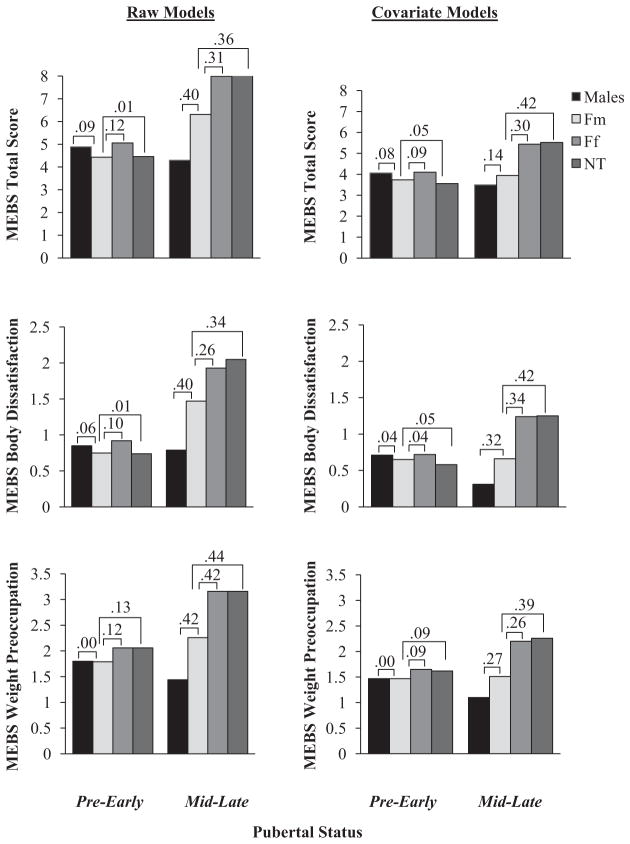

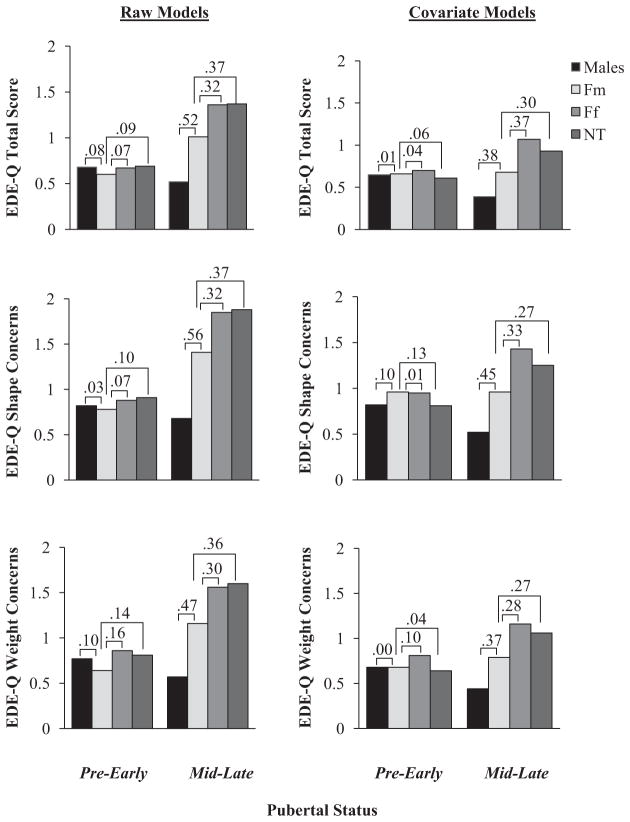

Main effects of twin type, within each pubertal group, further confirmed hypotheses, and again, results were largely similar for models with and without covariates (see Table 3). As expected, there were no significant differences in levels of DE attitudes between twin types in the pre-early pubertal group (see Table 3; ds = .00 to .16; see Figures 1 and 2); however, significant main effects for twin type were present in the mid-late pubertal group (see Table 3). Pairwise comparisons in the mid-late pubertal group indicated that Ff twins and nontwins showed similar levels of DE attitudes (i.e., ds = .00 to .13; also see Table 3 and Figures 1 and 2), and importantly, both of these female groups exhibited significantly higher levels of DE attitudes than males in mid-late puberty (see Table 3; ds = .39 to .92, see Figures 1 and 2). As predicted, Fm twins fell intermediate to male twins and other females in levels of DE attitudes in mid-late puberty (see Table 3), with differences in the small to moderate range (see Figures 1 and 2; males < Fm twins, ds = .14 to .56; Fm twins < Ff twins, ds = .26 to .42; Fm twins < nontwin females, ds = .27 to .44). Linear contrasts also confirmed significant linear trends in levels of DE attitudes across twin types (males < Fm twins < Ff twins and nontwins) in the mid-late pubertal group only, even after controlling for covariates (standardized contrast estimates [standard errors]: pre-early puberty = 0.02 to 0.17 (0.10 to 0.15), ps = .28 to .97; mid-late puberty = 0.35 to 0.71 [0.13 to 0.17], ps < .01). Overall, findings suggest that sex differences (males < females) and the masculinization of several DE attitudes in Fm twins become prominent during mid-late puberty, and importantly, age, ethnicity, anxiety, depression, autonomy difficulties, BMI, and being reared with a male sibling do not account for these effects.

Table 3.

GLMM Main Effects and Pairwise Comparisons Examining Sex and Twin Type Differences in Pubertal Groups

| Mean (SE)

|

Main Effect Twin Type F (df = 3, 421–448) | Pairwise comparisons, t value

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ff vs. NT | Males vs.

|

Fm vs.

|

|||||||||

| Males | Fm | Ff | NT | Ff | NT | Males | Ff | NT | |||

| Raw model | |||||||||||

| Pre-Early pubertal group

|

|||||||||||

| MEBS | |||||||||||

| Total score | 4.89 (0.51) | 4.43 (0.88) | 5.06 (0.64) | 4.46 (1.18) | 0.16 | 0.45 | −0.21 | 0.33 | −0.49 | −0.58 | −0.02 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.85 (0.17) | 0.75 (0.30) | 0.92 (0.21) | 0.74 (0.39) | 0.10 | 0.40 | −0.26 | 0.25 | −0.31 | −0.47 | 0.01 |

| Weight preoccupation | 1.80 (0.21) | 1.79 (0.35) | 2.06 (0.26) | 2.06 (0.48) | 0.27 | 0.00 | −0.81 | −0.51 | −0.03 | −0.63 | −0.47 |

| EDE-Q | |||||||||||

| Total score | 0.68 (0.10) | 0.60 (0.17) | 0.67 (0.12) | 0.69 (0.22) | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.45 | −0.33 | −0.32 |

| Shape concerns | 0.82 (0.13) | 0.78 (0.23) | 0.88 (0.16) | 0.91 (0.29) | 0.06 | −0.10 | −0.27 | −0.28 | −0.18 | −0.35 | −0.36 |

| Weight concerns | 0.77 (0.12) | 0.64 (0.22) | 0.86 (0.16) | 0.81 (0.28) | 0.22 | 0.16 | −0.46 | −0.13 | −0.54 | −0.80 | −0.46 |

| Mid-Late pubertal group

|

|||||||||||

| MEBS | |||||||||||

| Total score | 4.30 (0.80) | 6.31 (0.83) | 7.99 (0.55) | 8.13 (0.77) | 5.60*** | −0.14 | −3.81*** | −3.44*** | 1.92† | −1.70† | −1.60 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.79 (0.27) | 1.47 (0.28) | 1.93 (0.18) | 2.05 (0.26) | 5.15** | −0.40 | 33.57*** | −3.43*** | 1.90† | −1.39 | −1.54 |

| Weight preoccupation | 1.44 (0.32) | 2.27 (0.33) | 3.18 (0.22) | 3.16 (0.31) | 7.47*** | 0.05 | −4.43*** | −3.85*** | 1.97* | −2.27* | −1.96† |

| EDE-Q | |||||||||||

| Total score | 0.52 (0.15) | 1.01 (0.16) | 1.36 (0.11) | 1.37 (0.15) | 7.74*** | −0.04 | −4.53*** | −4.03*** | 2.52** | −1.84† | −1.66† |

| Shape concerns | 0.68 (0.21) | 1.41 (0.21) | 1.85 (0.14) | 1.88 (0.19) | 8.50*** | −0.12 | −4.73*** | −4.26*** | 2.69** | −1.76† | −1.66† |

| Weight concerns | 0.57 (0.20) | 1.16 (0.21) | 1.56 (0.13) | 1.60 (0.18) | 6.82*** | −0.17 | −4.21*** | −3.85*** | 2.32* | −1.68† | −1.62 |

| Covariate model | |||||||||||

| Pre-Early pubertal group

|

|||||||||||

| MEBS | |||||||||||

| Total score | 4.07 (0.42) | 3.74 (0.63) | 4.10 (0.51) | 3.56 (0.73) | 0.26 | 0.68 | −0.07 | 0.69 | −0.55 | −0.54 | 0.20 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.71 (0.16) | 0.65 (0.27) | 0.72 (0.19) | 0.58 (0.28) | 0.10 | 0.47 | −0.06 | 0.47 | −0.26 | −0.27 | 0.19 |

| Weight preoccupation | 1.47 (0.20) | 1.47 (0.30) | 1.65 (0.26) | 1.62 (0.36) | 0.23 | 0.07 | −0.76 | −0.41 | −0.02 | −0.56 | −0.36 |

| EDE-Q | |||||||||||

| Total score | 0.65 (0.10) | 0.66 (0.16) | 0.70 (0.12) | 0.61 (0.17) | 0.09 | 0.45 | −0.43 | 0.20 | −0.05 | −0.25 | 0.20 |

| Shape concerns | 0.82 (0.13) | 0.96 (0.23) | 0.95 (0.16) | 0.81 (0.23) | 0.30 | 0.54 | −0.81 | 0.04 | 0.60 | −0.01 | 0.48 |

| Weight concerns | 0.68 (0.12) | 0.68 (0.20) | 0.81 (0.15) | 0.64 (0.20) | 0.30 | 0.72 | −0.84 | 0.19 | −0.04 | −0.61 | 0.13 |

| Mid-Late pubertal group

|

|||||||||||

| MEBS | |||||||||||

| Total score | 3.50 (0.52) | 3.95 (0.54) | 5.44 (0.53) | 5.52 (0.62) | 5.75*** | −0.15 | −3.49*** | −3.18** | 0.78 | −2.82** | −2.58** |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.31 (0.16) | 0.66 (0.20) | 1.24 (0.18) | 1.25 (0.23) | 9.58*** | −0.05 | −4.88*** | −4.20*** | 1.69† | −2.81** | −2.52** |

| Weight preoccupation | 1.10 (0.24) | 1.51 (0.26) | 2.20 (0.28) | 2.26 (0.32) | 6.27*** | −0.23 | −3.88*** | −3.65*** | 1.49 | −2.63** | −2.54** |

| EDE-Q | |||||||||||

| Total score | 0.39 (0.12) | 0.68 (0.13) | 1.07 (0.11) | 0.93 (0.13) | 8.93*** | 1.08 | −5.03*** | −3.58*** | 2.03* | −2.79** | −1.60 |

| Shape concerns | 0.52 (0.15) | 0.96 (0.17) | 1.43 (0.15) | 1.25 (0.17) | 9.73*** | 1.07 | −5.26*** | −3.80*** | 2.28* | −2.63** | −1.48 |

| Weight concerns | 0.44 (0.15) | 0.79 (0.16) | 1.16 (0.14) | 1.06 (0.16) | 6.71*** | 0.66 | −4.33*** | −3.30*** | 1.94† | −2.16* | −1.38 |

Note. Raw models were not adjusted for any covariate. Covariate models were adjusted for age, ethnicity, body mass index, autonomy difficulties, and anxiety and depression symptoms. EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; MEBS = Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey; Ff = females with a female co-twin; Fm = females with a male co-twin; NT = nontwin females; df = degrees of freedom; GLMM = generalized linear mixed models; SE = standard error.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Cohen’s d effect sizes for pairwise comparisons between twin types on the MEBS in pre-early and mid-late puberty, for raw and covariate models. Results depict effect sizes between opposite-sex female twins and the other twin/nontwin groups. Y-axis values represent mean MEBS scores. MEBS = Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey. Ff = females with a female co-twin, Fm = females with a male co-twin, NT = nontwin females.

Figure 2.

Cohen’s d effect sizes for pairwise comparisons between twin types on the EDE-Q in pre-early and mid-late puberty, for raw and covariate models. Results depict effect sizes between opposite-sex female twins and the other twin/nontwin groups. Y-axis values represent mean EDE-Q scores. EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; Ff = females with a female co-twin; Fm = females with a male co-twin; NT = nontwin females.

Because same-sex male (i.e., Mm) and female (i.e., Ff) twin groups included monozygotic (Mm, n = 48; Ff, n = 78) and dizygotic (Mm, n = 40; Ff, n = 100) twins, we wanted to ensure that any twin-type mean differences in DE attitudes could not be accounted for by increased concordance for high levels of DE attitudes in Ff monozygotic twins or low levels in Mm monozy-gotic twins. We therefore reran all GLMMs (a) with only dizygotic twins, and (b) with all twins, covarying zygosity. Results were unchanged (data not shown), suggesting that our inclusion of monozygotic twins did not bias results. This is perhaps not surprising, given that there were no monozygotic versus dizygotic differences in levels of DE attitudes within Ff twins (ps = .33 to .93) or Mm twins (ps = .25 to .87).

Additionally, because nontwin females’ brothers could be up to four years older or younger, the amount of time siblings spent together may have varied (e.g., decreased interaction with greater age spacing; Buhrmester & Furman, 1990). Thus, consistent with prior research (e.g., Culbert et al., 2008), post hoc analyses were conducted to ensure that the magnitude of age differences between nontwin females and their brothers did not account for mean differences in DE attitudes between Fm twins and nontwin females. Correlations between DE attitudes and age differences were small and nonsignificant (rs = .04 to .16, all ps > .05), and GLMMs that included only nontwin females with brothers ≤1 or 2 years older/younger yielded identical patterns of results as the full sample (data not shown).

Discussion

This study was the first to investigate whether the masculinizing effects of prenatal testosterone exposure on DE attitudes emerge during puberty. Consistent with hypotheses, there were no significant differences in mean levels of DE attitudes across all males and females during pre-early puberty. In contrast, sex differences and masculinized (i.e., lower) DE attitudes in Fm twins emerged during mid-late puberty. Specifically, during mid-late puberty, males exhibited substantially lower levels of DE attitude than Ff twins and nontwin females, and Fm twins fell intermediate to males and “other” females (i.e., Ff twins and nontwin females) on mean levels of DE attitudes. Results were consistent across two well-validated measures, suggesting that our findings are relevant to a range of DE attitudes and are not questionnaire specific. Together, findings indicate that prenatal testosterone’s masculinizing effects on DE attitudes likely emerge during puberty and thus may play a role in sex-differentiated risk for the development of DE attitudes after mid-puberty.

Several possible explanations for the prenatal testosterone/pubertal effects were investigated. The observed sex differences and masculinization of DE attitudes in mid-late pubertal Fm twins were not accounted for by important covariates. Fm twins in mid-late puberty exhibited lower levels of DE attitudes than nontwin females who were reared with a brother, and they fell intermediate to male and Ff twins on levels of DE attitudes, even after controlling for age, ethnicity, depression, anxiety, autonomy difficulties, and BMI. Other unexamined factors therefore likely play a role in the emergence of sex differences and masculinized DE attitudes in Fm twins during puberty.

As previously noted, the combined effects of prenatal and pubertal hormone exposure may be important. Elevated prenatal testosterone exposure, as is expected in Fm twins, may organize the central nervous system to be “male-like.” Decreased sensitivity to ovarian hormones during puberty could further promote the organization of a more “male-like” neural system, particularly because puberty is now recognized as a second major organizational period of development (Schulz et al., 2009). Circulating levels of ovarian hormones on a masculinized neural system may subsequently fail to “activate” genetic (Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2010, 2012) and phenotypic risk for DE attitudes during and after mid-puberty, and thus result in more male-like patterns (i.e., lower levels) of DE attitudes. These same effects may underlie sex differences in risk, where in males, elevated prenatal testosterone exposure masculinizes the central nervous system and increases sensitivity to testosterone during puberty (Wade, 1972). Increased responsiveness to testosterone during puberty may further contribute to a “male-like” nervous system that protects against genetic and phenotypic activation of DE attitudes during and after mid-puberty (Klump et al., 2012).

If these hypotheses are confirmed in future research, it will be important to examine whether the effects of puberty and gonadal hormones are acting via peripheral or central mechanisms. Several neurobiological factors (e.g., leptin, cholecystokinin, serotonin), which are disrupted in eating disorders (Kaye, 2008), mediate estrogen’s effects on female-typical eating behavior in animals (see Asarian & Geary, 2006). Estrogen’s effects on risk for DE attitudes in this study, and DE attitudes and behaviors in previous work (e.g., Edler et al., 2007; Klump et al., 2008; Klump et al., 2013; Racine et al., 2012), may therefore occur via altered sensitivity to peripheral negative feedback controls of eating behavior and body weight, including satiation (e.g., cholecystokinin) or adiposity (e.g., leptin) signals (Asarian & Geary, 2006). Estrogen could also interact with central neurotransmitter mechanisms, such as serotonin synaptic activity, to alter risk for DE attitudes and/or behaviors (Asarian & Geary, 2006). Differentiation of these mechanistic processes would have important implications for understanding how gonadal hormones exert etiologic effects on DE attitudes and/or behaviors during puberty. Our initial data provide a foundation for future studies to replicate these results and to begin to investigate downstream mediators of effects.

Whether gonadal hormone effects are specific to DE variables or are neurobiological processes underlying a range of sex-differentiated psychopathology is another important area for future research. Prenatal testosterone’s masculinizing effects on DE attitudes emerged during puberty, even after controlling for confounding factors, suggesting unique effects on DE attitudes; however, this does not rule out the possibility that some gonadal hormone processes may be shared with other correlated phenotypes (e.g., anxiety, depression). Indeed, organizational and activational influences of gonadal hormones underlie the development and expression of many sex-differentiated characteristics (Breedlove, 1994; Schulz et al., 2009). We therefore conducted post hoc analyses with our anxiety and depression scores as outcome measures instead of covariates. Consistent with the pubertal moderation effects observed for DE attitudes, Fm twins showed masculinized levels of anxiety, that is, mean anxiety scores for Fm twins fell intermediate between males and Ff twins (males < Ff twins, d = .42; males < Fm twins, d = .21; Fm twins < Ff twins, d = .24), but only in mid-late puberty (twin type × puberty, p = .006; twin type main effects: pre-early puberty, p = .55, mid-late puberty, p = .007). In contrast, there were no differences in the effects of puberty across twin types for depression (main effect twin type, p = .93; main effect puberty, p = .02; twin type × puberty, p = .19). These findings corroborate other research showing stronger etiologic links between anxiety and DE (than depression and DE; e.g., Culbert et al., 2008; Keel, Klump, Miller, McGue, & Iacono, 2005) and highlight gonadal hormones as potential shared risk factors. Identifying gonadal hormone mechanisms that are shared versus unique between sex-differentiated psychopathology could provide new insights into neurobiological and genetic processes important for DE variables and other complex disorders.

It will also be important for future research to examine whether the effects of prenatal testosterone exhibit other developmental shifts across the life span. Although previous studies have assumed that prenatal testosterone’s masculinizing effects on DE pathology remain static across development, the current study challenges this assumption by showing that developmental factors (i.e., puberty) may influence the expression of prenatal testosterone’s masculinizing effects. Speculatively, age-related factors might account for mixed findings in the literature. Prior studies using the opposite-sex versus same-sex twin pair design have differed in the age ranges assessed (i.e., mean ages from ~16 to 42 years), where evidence for prenatal testosterone effects were observed in young adulthood (Culbert et al., 2008, 2010; Raevuori et al., 2008) but not late adolescence (Baker et al., 2009; Culbert et al., 2010) or later adulthood (Lydecker et al., 2012). Moving forward, it will be important to explore the extent to which other factors (e.g., neurobiological, psychosocial) enhance or attenuate the expression of prenatal testosterone’s masculinization of DE attitudes and/or behaviors across development.

Several limitations must be noted. First, data were cross-sectional. Longitudinal studies will be necessary to ensure that the differences observed between pubertal groups are in fact reflective of within-person developmental changes. Second, sample sizes were relatively small for Fm twins and nontwin females. Future research should examine larger samples to replicate our findings and to investigate puberty’s effects across all stages of puberty (prepuberty vs. early puberty vs. mid-puberty vs. late puberty).

Third, whether elevated BMI altered the accuracy of self-reported pubertal development (e.g., breast development) in this study is largely unknown. However, post hoc analyses indicated high correlations (r = .87, p < .001; partial r = .86, p < .001) and good agreement (total sample, κ = .87; >85th percentile for BMI, κ = .80; <85th percentile for BMI, κ = .89) between child and parent ratings of pubertal development and pubertal status categorizations, irrespective of BMI. Physician ratings may, however, be a useful addition in future research, particularly given increasing rates of obesity.

Fourth, DE attitudes were measured in a community-based, rather than a clinical, sample. Whether these findings generalize to clinical eating disorders is therefore unclear. Nonetheless, the use of a clinical sample would be nearly impossible, given the low prevalence of eating disorders in males and during pre- to early adolescence. Because DE attitudes show prospective associations with eating disorder risk (Jacobi et al., 2004), and a variety of DE attitudes were observed in all of our sample groups, our findings are likely informative for etiologic models of eating disorders.

Fifth, self-report measures of DE attitudes were used, and due to psychometric limitations, some DE symptoms (e.g., binge eating, dietary restraint) could not be examined separately in analyses. Although the included scales showed good psychometric properties (and replicable factor structures, e.g., Marderosian et al., personal communication, July 7, 2011) in males and females, we do not know for certain whether the expression of DE pathology is the same for males and females in this or other studies. Drive for muscularity is a good example of the ways in which DE symptoms may be expressed differently between the sexes, as this symptom is more common in boys than drive for thinness (McCreary & Sasse, 2000). Future research should examine drive for muscularity and use interview-based assessments to examine complex constructs like binge eating and dietary restraint, as this may allow for a more comprehensive examination of gonadal hormone effects on the full spectrum of DE attitudes and behaviors in males and females.

Finally, we were unable to directly assess levels of prenatal testosterone exposure and instead used twin type as a proxy for differential exposure. It is difficult to overcome this limitation because direct measures of overall prenatal testosterone exposure in humans do not currently exist. Future studies should examine other models of prenatal testosterone exposure in humans (e.g., girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia) and animals (e.g., intra-uterine position effects) to confirm the emergence of masculinization of DE attitudes and/or behaviors during puberty.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health 1R21-MH070542-01 (Kelly L. Klump, Chery L. Sisk), 1R01-MH092377-01 (Kelly L. Klump, S. Alexandra Burt, Chery L. Sisk), F31-MH084470 (Kristen M. Culbert), T32-MH070343 (Kristen M. Culbert), and T32-MH082761 (Kristen M. Culbert); the Michigan State University Intramural Grants Program (71-IRGP-4831; Kelly L. Klump) and College of Social Science Faculty Initiatives Fund (Kelly L. Klump), Graduate Student Research Enhancement Award (Kristen M. Culbert), and John Hurley Endowed Fellowship (Kristen M. Culbert); the Academy for Eating Disorders Student Research Grant (Kristen M. Culbert); Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Dissertation Research Award (1412.SAP; Kristen M. Culbert); American Psychological Association Dissertation Research Award (Kristen M. Culbert); American Psychological Foundation Clarence J. Rosecrans Scholarship (Kristen M. Culbert). We thank Dr. Joel T. Nigg for his contribution to the data collection of this project via 1R21-MH070542-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these granting agencies. All authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Consistent with previous literature (e.g., Culbert et al., 2009; Klump, Perkins, Burt, McGue, & Iacono, 2007; Klump et al., 2010), the broad term DE attitudes and behaviors refers to a range of pathological attitudes/ cognitive features (e.g., body dissatisfaction, weight preoccupation, preoccupation with food) and behaviors (e.g., dietary restraint, binge eating, compensatory behaviors) that lie on a continuum with, and are core features of, eating disorders.

For further information, see http://www.michigan.gov/mdch

The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (previously known as the Minnesota Eating Disorder Inventory) was adapted and reproduced by special permission of Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Florida 33549, from the Eating Disorder Inventory (collectively, EDI and EDI-2) by Garner, Olmstead, Polivy, Copyright 1983 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Further reproduction of the MEBS is prohibited without prior permission from Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Onset of menses occurs relatively late in puberty, yet two females scored in the pre-early pubertal range (i.e., self-report PDS scores = 2.2 and 2.4) despite being postmenarche. We utilized parent PDS ratings and determined that these participants likely underreported their development, and thus they were recoded into the mid-late pubertal group.

Although selected models provided the best fit (e.g., lowest AIC), results were nearly identical across all tested models: default Mixed Linear Models (i.e., normal distribution with identity link), Loglinear, and Negative Binomial. These data are not shown.

None of the authors have financial conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Kristen M. Culbert, University of Chicago

S. Marc Breedlove, Michigan State University.

Cheryl L. Sisk, Michigan State University

S. Alexandra Burt, Michigan State University.

Kelly L. Klump, Michigan State University

References

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Worthman CM. Pubertal changes in hormone levels and depression in girls. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:1043–1053. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799008946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarian L, Geary N. Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B, Biological Sciences. 2006;361:1251–1263. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JH, Lichtenstein P, Kendler KS. Intrauterine testosterone exposure and risk for disordered eating. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194:375–376. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DD, Zucker I. Sex differences in body weight and eating: Organization and activation by gonadal hormones in the rat. Physiology & Behavior. 1971;7:27–34. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove SM. Sexual differentiation of the human nervous system. Annual Review of Psychology. 1994;45:389– 418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45.020194.002133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove SM. Organizational hypothesis: Instances of the fingerpost. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4116– 4122. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0041. doi:101.1210/en.2010-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1387–1398. doi: 10.2307/1130750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Klump KL. The Michigan State University Twin Registry: An update. Twin Research and Human Genetics. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.87. in press. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/thg.2012.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Byrne SM, Allen KL, Lampard AM, Dove ER, Fursland A. The factor structure of the eating disorder examination in clinical and community samples. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:260–265. doi: 10.1002/eat.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Stewart DA, Fairburn CG. Eating disorder examination questionnaire: Norms for young adolescent girls. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:625–632. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: Relationship to gender and ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:166–175. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KM, Breedlove SM, Burt SA, Klump KL. Prenatal hormone exposure and risk for eating disorders: A comparison of opposite-sex and same-sex twins. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:329–336. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KM, Breedlove SM, Nigg JT, Sisk CL, Burt SA, Klump KL. Prenatal testosterone exposure and developmental differences in risk for disordered eating. Paper presented at the Eating Disorders Research Society Meeting; Cambridge, MA. 2010. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KM, Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Klump KL. Puberty and the genetic diathesis of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:788–796. doi: 10.1037/a0017207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe TP, Stevens R. Effects of ovariectomy, estrogen treatment, and CI-628 on food intake and body weight in female rats treated neonatally with gonadal hormones. Physiology & Behavior. 1983;31:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaluwé V, Braet C. Assessment of eating disorder psycho-pathology in obese children and adolescents: Interview versus self-report questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:799– 811. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edler C, Lipson SF, Keel PK. Ovarian hormones and binge eating in bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:131–141. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert J. Unpublished dissertation. Michigan State University; East Lansing, MI: 2007. Separation-individuation and disordered eating in adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Bèglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16:363–370. doi:1995-15839-001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreiro F, Seoane G, Senra C. Gender-related risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms and disordered eating in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;41:607–622. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry RT, Wade GN. Sex differences in sensitivity of food intake, body weight, and running-wheel activity to ovarian steroids in rats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1976;90:747–754. doi: 10.1037/h0077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Sanborn K. Puberty and the emergence of gender differences in psychopathology. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:49–58. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Stewart A. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:19– 65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye W. Neurobiology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Physiology & Behavior. 2008;94:121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Klump KL, Miller KB, McGue M, Iacono WG. Shared transmission of eating disorders and anxiety disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:99–105. doi: 10.1002/eat.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Heath AC, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ. A population-based twin study of alcoholism in women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;268:1877–1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490140085040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL. Unpublished thesis. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, MN: 1996. The validity of the equal environments and representativeness assumptions for twins at risk for the development of eating disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Burt SA. The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR): Genetic, environmental and neurobiological influences on behavior across development. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:971–977. doi: 10.1375/twin.9.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Culbert KM, Slane JD, Burt SA, Sisk CL, Nigg JT. The effects of puberty on genetic risk for disordered eating: Evidence for a sex difference. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:627–637. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Gobrogge KL, Perkins P, Thorne D, Sisk CL, Breedlove SM. Preliminary evidence that gonadal hormones organize and activate disordered eating. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:539–546. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Keel PK, Culbert KM, Edler C. Ovarian hormones and binge eating: Exploring associations in community samples. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1749–1757. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Keel PK, Racine SE, Burt SA, Neale M, Sisk C, Hu JY. The interactive effects of estrogen and progesterone on changes in emotional eating across the menstrual cycle. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:131–137. doi: 10.1037/a0029524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Keel PK, Sisk C, Burt SA. Preliminary evidence that estradiol moderates genetic influences on disordered eating attitudes and behaviors during puberty. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1745–1753. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Perkins PS, Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono W. Puberty moderates genetic influences on disordered eating. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:627– 634. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psycho-pharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, De Young KP, Anderson DA. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): Norms for undergraduate men. Eating Behaviors. 2010;11:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JB, Green C, Millon T. The Separation-Individuation Test of Adolescence. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1986;50:123–139. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5001_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydecker JA, Pisetsky EM, Mitchell KS, Thornton LM, Kendler KS, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Mazzeo SE. Association between co-twin sex and eating disorders in opposite sex twin pairs: Evaluations in North American, Norwegian, and Swedish samples. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2012;72:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid JA, Lopez-Bote C, Martin E. Effects of neonatal androgenization on the circadian rhythm of feeding behavior in rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1993;53:329–335. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90213-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malas MA, Dogan S, Evcil EH, Desdicioglu K. Fetal development of the hands, digits, and digit ratios (2D:4D) Early Human Development. 2006;82:469– 475. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker J, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marderosian A, Wu Y, Culbert KM, Burt SA, Nigg JT, Klump KL. Psychometric properties of the Minnesota Eating Behaviors Survey in pre-adolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Personal communication. 2011. Jul 7,

- Marsden P, Meyer C, Fuller M, Waller G. The relationship between eating psychopathology and separation-individuation in young nonclinical women. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190:710–713. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200210000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Sasse DK. An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:297–304. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. A masculinizing effect on the auditory systems of human females having male co-twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:11900–11904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EM. Prenatal sex hormone transfer: A reason to study opposite-sex twins. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;17:511–529. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90088-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beaumont PJV. Temporal stability of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36:195–203. doi: 10.1002/eat.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine SE, Culbert KM, Keel PK, Sisk CL, Burt SA, Klump KL. Differential associations between ovarian hormones and disordered eating symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:333–344. doi: 10.1002/eat.20941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raevuori A, Kaprio J, Hoek HW, Sihvola E, Rissanen A, Keski-Rahkonen A. Anorexia and bulimia nervosa in same-sex and opposite-sex twins: Lack of association with twin type in a nationwide study of Finnish twins. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1604–1610. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan BC, Vandenbergh JG. Intrauterine position effects. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26:665–678. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KM, Molenda-Figueira HA, Sisk CL. Back to the future: The organizational-activational hypothesis adapted to puberty and adolescence. Hormones and Behavior. 2009;55:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science. 2011;22:1359–1366. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Hawkeswood SE, Joiner TE. The measure of a man: Associations between digit ratio and disordered eating in males. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:543–548. doi: 10.1002/eat.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ranson KM, Klump KL, Iacono WG, McGue M. The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey: A brief measure of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2005;6:373–392. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade GN. Gonadal hormones and behavioral regulation of body weight. Physiology & Behavior. 1972;8:523–534. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90340-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TD, Byrne S, Bryant-Waugh R. The eating disorder examination: Norms and construct validity with young and middle adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:551–558. doi: 10.1002/eat.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker I. Hormonal determinants of sex differences in saccharin preference, food intake and body weight. Physiology & Behavior. 1969;4:595–602. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(69)90160-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]