Abstract

This systematic review of mixed methods studies focuses on factors that can facilitate or limit the implementation of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in clinical settings. Systematic searches of relevant bibliographic databases identified studies about interventions promoting ICT adoption by healthcare professionals. Content analysis was performed by two reviewers using a specific grid. One hundred and one (101) studies were included in the review. Perception of the benefits of the innovation (system usefulness) was the most common facilitating factor, followed by ease of use. Issues regarding design, technical concerns, familiarity with ICT, and time were the most frequent limiting factors identified. Our results suggest strategies that could effectively promote the successful adoption of ICT in healthcare professional practices.

Keywords: Systematic review, Adoption factors, Information and communication technologies (ICTs), ICT adoption by healthcare professionals

Introduction

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) encompass all digital technologies that facilitate the electronic capture, processing, storage, and exchange of information. ICTs have the potential to address many of the challenges that healthcare systems are currently confronting. ICT applications could improve information management, access to health services, quality and safety of care, continuity of services, and costs containment [1]. What is more, patients want clinicians to use ICTs [2]. With increasing computerisation in every sector of activity, ICTs are expected to become tools that are part of healthcare professional practice. Nevertheless, it appears that several ICT applications remain underused by healthcare professionals [3, 4]. Healthcare organisations, particularly physician practices, are often pointed out as noticeably lagging behind in the adoption of these technologies [5]. Human and organisational factors have frequently been identified as the main causes of ICT implementation failure [6–8].

Although barriers and facilitators to ICT adoption in healthcare settings are described to a certain extent in the literature, only a few studies have systematically reviewed factors influencing the adoption of different types of ICTs [5, 9–12]. Furthermore, there is no consensus on the categorisation of barriers and facilitators related to ICT adoption since most of these reviews have looked at those factors from a specific angle. In addition, they have rarely considered the external validity of factors that could affect healthcare professionals’ ICT adoption.

The present study aimed at systematically reviewing factors that are positively or negatively associated with ICT adoption by healthcare professionals in clinical settings. This review complements a Cochrane systematic review on the effectiveness of interventions for promoting ICT adoption [13]. Furthermore, this review allowed us to highlight the differences and similarities of factors associated with adoption between ICT types.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

To account for the different types of studies on factors affecting ICT adoption by healthcare professionals, a mixed studies review was conducted. A mixed studies review is a literature review that concomitantly examines qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. A mixed studies review could be conceptualized as a mixed methods research study where data consist of the text of papers reporting primary qualitative and quantitative studies in addition to mixed methods studies [14].

A study was included if: (1) a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method methodology used to collect original data was described; (2) the intervention for promoting the adoption or the use of a specific ICT in healthcare settings (i.e. a planned strategy that goes beyond the simple provision of or access to the ICT application) was described; (3) the outcomes measured included barriers and/or facilitators to the adoption of a specific ICT application by healthcare professionals, including professionals in training (residents, fellows, and other registered health professionals) in a clinical setting. Studies reported in French, English, or Spanish were included.

Search strategy

The literature search performed for the Cochrane review on the effectiveness of interventions for promoting ICT adoption [13] was used for this review. The search strategy based on the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) search strategy and including selected ICT terms and free text terms relating to ICT is described elsewhere [13]. The following databases were searched for studies published between January 1st, 1990 and October 1st, 2007:MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Ovid, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Biosis Previews, PsycINFO, Current Content, Health Services/Technology Assessment Text (HSTAT), Dissertation Abstracts, Educational Resources Information (ERIC), Proquest, ISI Web of Knowledge, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences (LILACS), and Ingenta. We also searched publications citing the retrieved articles through the ISI Science Citation Index. An update of the review was made on January 12th, 2010 in MEDLINE and EMBASE.

Data selection

Two reviewers screened all titles and abstracts for potentially eligible studies. Full texts of all potentially eligible studies were assessed by the same two reviewers.

Data abstraction and classification of barriers and facilitators

A data extraction form was developed applying a combination of deductive and inductive methods related to the classification of reported barriers and facilitators to ICT adoption in healthcare settings. Following established theoretical concepts [5, 9, 15–18] and previous work by Legaré et al. that developed a classification of barriers and facilitators to implementation of shared decision-making in healthcare settings [19–21] a data extraction form was created. This grid allowed the initial classification of the factors facilitating or limiting ICT adoption. The grid was improved as other emergent categories were added during the review process.

Data regarding authors, year of publication, type of technology, participants and sample size, care setting, intervention, study design, data collection, and barriers and facilitators were abstracted.

Quality assessment

A scoring system for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies developed by Pluye et al [14] was used in this review. This appraisal tool calculates the quality score of a study by dividing the number of positive responses (presence of criteria that was scored 1) by the number of “relevant criteria” × 100. This assessment was performed by two independent reviewers and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. This appraisal tool could be used to exclude studies based on their poor methodological quality. However, given the exploratory purpose of our review, we chose not to exclude any studies on the basis of their methodological quality. The quality scores of the studies included are presented in Appendix 1.

Appendix 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Country | Technology | Participants/ sample size (RR if appropriate) |

Setting of care |

Intervention | Methodology/ design |

Data collection |

Main findings | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarts 2004 |

Netherlands | CPOE | Project leaders, members of the pilot project/10 |

Teaching hospital |

Implementation with a project team (key individuals representing the medical departments and the hospital board). | Qualitative/ longitudinal |

Interviews, observation, document analysis |

The full implementation of CPOE was halted. The information system did not fit well with work practices. | 83 % |

| Abate 1992 |

USA | CIRT (online databases) |

Physicians/30, nurses/23, pharmacists/12 |

Various (community + academic) |

Access to ICT with training sessions, and instructional handouts | Quantitative/ cross sectional |

Attitude survey |

Lack of time was a major factor which limited use of the services. Users felt that the services did not fit in well with their daily work routine. | 67% |

| Abdolrasulnia 2004 |

USA | CIRT (Internet- based guidelines |

Physicians/ 210 (47.2%) |

Community- based primary care |

E-mail contacts announcing and reminding of an online guideline | Quantitative | Questionnaire | E-mail course reminders may enhance recruitment of physicians to interventions designed to reinforce guideline adoption. | 100% |

| Abubakar 2005 |

England | PDA | Public health consultants/NS |

On call service for health protection |

Development and pilot of an on-call pack with presentation at training meeting for improvement | Mixed | Questionnaire | The system provided a fast, reliable and easily maintained source of information for the public health on-call team. | 33% |

| Adaskin 1994 |

Canada | HIS | Nurses/20 | Teaching hospital |

An 11-month implementation period including planning, communication and training process (one 8-hour day) | Qualitative/ case study |

Interviews | Recommendations: shorter training; slower pace of implementation; best planning (become familiar with the system before implementation, visible ongoing administrative support, promotion, etc.) | 83% |

| Adler 2003 |

USA | Computer aided instruction software |

Residents/47 | Paediatric emergency department |

Demonstration of the program to each resident |

Mixed/ descriptive study |

Questionnaire, focus group |

Generally positive ratings to learning-based CAI program. Time of use and level of training may be important factors in CAI use. | 75% |

| Af Klercker 1998 |

Sweden | CDSS | Nurses/4 Physician/1 |

Primary care health center |

User manual placed by all computers | Qualitative/ action research |

Focus groups | The acceptance of a new product relies upon the human rather than on the electronic communication kind. Success will depend on the introductory efforts put into the project. |

83% |

| Al Farsi 2006 |

Oman | EMR | Physicians/ 66 (94%) |

Secondary hospital |

1-week training program | Quantitative/ survey |

Questionnaire | Physicians are generally satisfied with the EMR, received adequate training, and believe the system can improve quality care for patients. | 100% |

| Allen 2000 |

Canada | Computer and Internet |

Physicians/ 30 (46%) |

Not specified | Computer workshops (4 or 5 day-long): lecture and discussion + demonstration + practice | Quantitative/ survey |

Questionnaire | The number of physicians buying and using computers has increased. | 67% |

| Al-Qirim 2003 |

Australia | Telemedicine | Physicians/NS | Rural hospital |

Trial and assessment with inclusion of clinicians during the assessment phase | Qualitative/ case study |

Interviews | Importance of the product champion for a successful adoption and diffusion of teledermatology. | 83 % |

| André 2008 |

Norway | Handheld computer (PDA) |

Nurses/13, physicians/2, physiotherapists/2 |

Hospital and outpatient clinic |

Implementation prepared from a study of unsuccessful previous implementation process 3 years earlier | Qualitative | Interviews | Healthcare personnel lacked a sense of ownership for the tool, which resulted in unsuccessful implementation. Need for skilled and motivated key personnel in the unit. Training program must focus on influencing participants’ attitudes of toward this kind of tool. | 100% |

| Angier 1990 |

USA | CIRT (online databases) |

Fellows, residents, pharmacists and nurses/29 |

Teaching hospital (oncology unit) |

Accessibility of computers + short training (30-minute session) + manual with a user aid sheet | Mixed | Interviews | Most users perceived the system to be useful and considered immediate, direct access to it as convenient and time-saving. | 67% |

| Bailey 2000 |

USA | EMR | Nurses, physicians, managers, and system staff/NS |

Teaching hospital |

Implementation of a clinical information system (on a 2-year period) with system training | Qualitative/ ethnography |

Participant observation, interviews |

Primacy of considering the complex interactions among users, information systems and organisations to assure that systems perform as tool to support information work. | 100% |

| Barrett 2009 |

Australia | Telehealth program |

NS | 12 healthcare sites(mainly rural) |

IT and clinical support available + managerial and organisational support + 1-hour small group training at each site. All individual attended a minimum of 2 training session. |

Qualitative | Interviews | Of the 12 participating sites, 4 did not enrol any patients, and only 2 successfully incorporated the system into regular practice. Disease burden of the patient group, funding models and workforce shortages frustrated the successful adoption. |

50% |

| Barsukiewiez 1998 |

USA | EMR | Physicians/13 | Primary care sites (3) |

Basic and more intensive (16 h) training + a team responsible for managing the implementation | Qualitative/ ethnography |

Participant observation, interviews |

Substantial change in work habits, increased demands on physician time, and perceived changes in the patient-physician relation. | 100% |

| Bartlett 2003 |

USA | e-Learning | Resident physicians/ 26 (88%) |

Teaching hospital |

Distribution of a CD-ROM designed to provide ready access to the department’s curricula, study materials, and Internet resources | Quantitative/ survey |

Questionnaire | The CD-ROM has not been fully integrated into the residency program. The greatest obstacle to its use is the lack of computer resources in the department. | 67% |

| Bossen 2007a |

Denmark | EMR (problem oriented medical record) |

Nurses, physicians and others/13 (interviews) |

Hospital department |

Trial test of a Computerized problem-oriented medical record + Training (2 periods: about 12 h) | Qualitative/ ethnographic case study |

Interviews, participant observation, focus group |

Use of the CPOMR does not adequately support complex clinical work. | 83% |

| Bossen 2007b |

Denmark | Electronic medication plan |

Physicians and nurses/9 |

Hospitals (3) | Cooperation of clinicians in the development through a series of workshops + test of the EMP in daily clinical work (8 weeks) + training of experts and super users | Qualitative/ ethnographic case study |

Participant observation, interviews |

The test implementation did not become part of daily clinical work. But it brought forward a number of issues that were important for the further development of the EMP. | 83% |

| Cabell 2001 |

USA | CIRT (online databases) |

Residents/ 48 (98%) |

Teaching hospital |

On-hour didactic session in small group (use of well-built clinical question cards and practical sessions) | Quantitative/ RCT |

Questionnaire | A single educational intervention increased resident searching activity. | 67 % |

| Cheng 2003 | China | CIRT (online databases) |

Physicians, nurses and allied health prof./800 (71.5%) |

Public hospital |

3-hour training workshop (with supervised hands-on practice) | Quantitative/ RCT |

Questionnaire | The intervention increased the proportion of clinicians able to provide adequate clinical question. | 67% |

| Chisolm 2006 |

USA | CPOE | Physicians/17 | Teaching hospital |

Participation of clinicians in the development + training (2 h hands-on training session) | Mixed | Focus groups |

Relatively high use rate. Importance of administrative and clinical leaders in implementing and promoting the use of new clinical IT. |

100% |

| Connely 1992 |

USA | Laboratory Reporting System |

Physicians (interns, residents, others)/ 70 (80%) |

Neonatal intensive care unit |

Design committee: 5 to 8 individuals representing most of the major stakeholders in the system. No need for formal training program | Mixed | Questionnaire, observation and interviews |

The system seems to be remarkably well accepted and regarded even after nearly 6 years of use. | 58% |

| Crosson 2007 |

USA | Electronic prescribing |

Physicians/16, and staff members/31 |

12 ambulatory medical practices |

Implementation covered the costs of hardware, software, installation, training and ongoing support. Observational studies of practices before implementation exploring prescription workflow and expectations relating to implementation with physicians, office managers and staff members involved. | Qualitative/ case study |

Interviews and observation |

Before implementation, physicians and ambulatory practice leaders need to be aware of the capabilities and limitations of this technology. Practices should have timely access to IT and support for managing the organizational and workflow changes that HIT implementation demands. | 83% |

| Crowe 2004 |

Australia | Radiological information system/PACS |

Senior clinicians/NS |

Teaching hospital |

Implementation of the ICT with training of clinicians | Qualitative | Interviews | The introduction of the RIS/PACS has been well received by clinicians and is considered to have been helpful in clinical decision making and patient management. | 50% |

| Cumbers 1998 |

UK | CIRT (online databases) |

Clinicians from 14 clinical firms/NS |

Various (hospital and community) |

Feasibility study; training sessions | Mixed | Questionnaire and interviews |

7/14 firms developed effective ways of using the databases in their practice; 7 were dissatisfied with their training, computer facilities or lacked time. | 25% |

| D’Alessandro 1998 |

USA | CIRT (online databases) |

Physicians/ 93 (77%) |

Hospitals serving rural populations |

Access to computers with training sessions (an initial and follow-up on-site) + a technical support person + brief instructions affixed | Quantitative | Survey using a modified critical incident technique |

One year after deployment of the network: 33% had used the DHSL. | 100% |

| D’Alessandro 2004 |

USA | CIRT (online databases) |

Physicians (residents and faculty)/ 52 (89.6%) |

Children’s hospital (academic center) |

10-minutes personalized training session + 1 page handout summarized the session + an online tour + free access to MD consults | Quantitative/ Before and after not controlled |

Survey using a modified critical incident technique |

After the intervention, pediatricians were slightly less likely to pursue answers (95% to 89%); as successful (96% vs 93%); but took less time (8.3 minutes vs 19.6 min) in finding answers | 100% |

| Di Pietro 2008 |

Canada | PDA | Nurses/16 | Acute care and home care |

16 nurses tested the decision support system and attended a 2-hour workshop. | Qualitative/ cross sectional design |

Interviews | Ensuring thorough training and continued clinical support so that nurses are well prepared to use the PDA and outcomes assessment tool will ease the progression of use in everyday practice. | 67% |

| Doolin 2004 |

New Zealand |

HIS (medical management information system) |

Various (clinical directors, managers, medical consultants and nurses)/ 43 |

Regional hospital |

Series of demonstrations to doctors + organizational restructuring headed by a senior doctor acting as a clinician manager | Qualitative/ longitudinal case study |

Interviews | Resistance of doctors in front of the control strategy adopted by the hospital. Reinterpretation of the role of the information system, and with the continued resistance by doctors, relegation to a less significant role. | 83% |

| Dornan 2002 |

UK | e-Learning (electronic learning portfolio) |

Physicians/ 89 (94%) |

Various (continuing professional development) |

1 year free use of the PC + invitation to a training workshop + mail updates and tips on diary use + on-line support | Mixed/ longitudinal intervention study |

Questionnaire (qualitative and quantitative components) |

Poor use of PC Diary: PC Diary was used by 34% of enrolled physicians, but only 10% used it regularly. | 75% |

| Eley 2005 |

Australia | CDSS (for triage) |

Nurses/15 | Emergency department (2 hospitals) |

Training (self-directed training package) + test (use of the ICT to rate simulated scenarios) | Qualitative | Semi- structured interviews |

The tool was acceptable to users and was viewed as a viable alternative to current triage practice. | 100% |

| Firby 1991 |

UK | Computer | Nurses/14 | Regional renal unit |

Training sessions with practical sessions + written instructions at the computer station | Qualitative | Semi- structured interview |

Despite initial reservations, staff was generally positive about the medium. | 67% |

| Galligioni 2008 |

Italy | Electronic oncological patient record (EPR) |

Physicians and nurses/ NS |

Hospital | User-centred design of the EPR + user education and training (2 educational sessions and training on practical stimulation) + continuous assistance (on-site during the initial 2 weeks and permanent remote assistance after) | Quantitative | Questionnaire (after 2 weeks, 6 months and 6 years) |

The implementation was overall successful. User involvement in the system design, flexible web technology, education, training and continuous assistance have greatly facilitated user acceptance. | 33% |

| Granlien 2008 |

Denmark | EMR | Physicians/94, nurses/129, others/9; 232/54% |

Hospitals in one of Denmark’s five regions |

Attempts to address barriers toward use since the EMR deployment 3 years before: regional organisation and vendor have tried to improve the network, the computers and the design of the EMR + standard training program for new staff + extra information and training provided continuously |

Mixed | Survey with open question |

After 3 years of use, the adoption of the EMR by clinicians and its integration into work practices are far from the level necessary to attain the goals that motivated its acquisition. Considerable uncertainty exists about what the concrete barriers actually are. | 75% |

| Guan 2008 |

Canada | Online continuing medical education (CME) |

Physicians/158 and 10 facilitators |

Various (continuing medical education program) |

Content developed on the basis of the educational needs identified in a pre-program survey + evaluations of each module and feedback influencing the addition of later content + ongoing technical and learning support available to participants throughout the course | Mixed/ exploratory study |

Survey with open-ended questions |

Participation rate of physicians and facilitators in online social activities was very low. Lack of time and lack of peer response were perceived as main reasons for low participation. | 75% |

| Hains 2009 |

Australia | CDSS | Physicians/16; Nurses/30; Pharmacists/4 |

oncology outpatient department (6 public hospitals) |

CI-SCAT (the CDSS) was launched accompanied by a large-scale one-year education program | Qualitative | Interviews + observation |

At 3 years post launch, clinicians’ attitudes were generally positive, which translated into relatively high levels of CDSS use. Understanding end-users and their environment, is essential to ensure long-term sustainability and use of the system to its full potential. Continuing education and endorsement are also important. | 100% |

| Halamka 2006 |

USA | e-Prescribing | Various (clinicians and office staff)/NS |

Various | Implementation of regional pilots (demonstration of the software, offer a reduced rate, etc.) | Qualitative/ case studies |

Focus groups |

Importance of a well-resourced rollout that takes into account the barriers and lessons learned in early deployment. | 33% |

| Haynes 1990 |

Canada | CIRT (online databases) |

Physicians, housestaff and clinical clerks/158 (84%) |

University medical center |

Participants were offered a 2-hour introduction to online searching + 2 h of free search time | Quantitative/ longitudinal descriptive study |

Questionnaire | Most clinicians (81%) used MEDLINE after a brief introduction and they indicated that they would continue to do online searching, even if they had to pay. | 100% |

| Hibbert 2004 |

UK | Home telehealth |

Nurses/12 | Home nursing service |

Implementation of a home telehealth nursing service with weekly project meetings + nurse training sessions | Qualitative/ ethnographic study within a RCT |

Participant observation |

The specialist nurses did not share the generally positive view of telehealth. The new technology was a dynamic entity that changed through exposure to clinical practice and professional values. |

100% |

| Hier 2005 |

USA | EHR | Physicians/ 330 (36.3%) |

Faculty and housestaff |

Mandatory use of the EHR. Dictation of notes is available but incurs additional costs | Quantitative | Questionnaire | Both housestaff and faculty acceptance of an EHR was high. Central to acceptance is conservation of physician time. | 100% |

| Hou 2006 | Taiwan | Computer | Nurses (nurses and supervisors)/ 3 pairs |

1 hospital and 2 medical centers |

End user computing (EUC) strategy: 8-day training for clinical nurses who developed projects and promoted the informatics in their hospitals | Qualitative | Interviews | According to this study, end user computing strategy was successful so far. | 100% |

| Jaques 2002 |

USA | CIS (point-of -care systems) |

Nurses/43 in 3 surveys. Pre- implementation survey 122; Post: 89; and 12 months after: 100 |

Acute-care pediatric hospital |

Implementation of bedside computer systems with training (lectures and hands-on training) in one four-hour session (experimental group) | Quantitative/ a quasi- experimental design |

Surveys: pre- implementation, post and 12 months after |

Nurses in the experimental group (who used beside computers) had more positive attitude than the control group. | 100% |

| Joos 2006 | USA | EMR | Physicians/ 46 (66%) |

Ambulatory primary care and urgent care clinic in an academic hospital |

Installation of workstations (voluntarily usage) + training in scheduled classes + availability of IT support | Mixed | Semi- structured interviews to identify themes + survey |

This implementation was associated with perceived improvements in speed and communication efficiency and information synthesis capabilities. | 92% |

| Jotkowitz 2006 |

USA | PDA | Residents/ 90 = 65 (80%) unsubsidized group; 25 (86%) subsidized group |

2 teaching hospitals |

Subsidized fully residents’ purchase of PDAs at one of the hospitals + introduction to basic PDA functioning | Quantitative | Questionnaire | Subsidized group of residents perceived PDA to be less useful and more fragile than residents who purchase a PDA themselves. Merely providing the PDA does not necessarily ensure its adoption. Intensive training and reinforcement are needed to increase the perceptions of positive benefit. |

67% |

| Jousimaa 1998 |

Finland | CIRT (computerized guidelines) |

Physician/46 | General practice |

Distribution of electronic guidelines (diskettes or CD-Rom) + local training sessions organised in several centers. | Quantitative/ descriptive follow up study |

Interview using semi- structured questionnaires (3 times) |

After 1 year of use, opinions had become slightly more positive about guidelines. Usage frequency was associated with having the computer in the office. Technical support was also important. | 33% |

| Joy 2002 | USA | PDA | Residents/24 | Gynaecology residency program |

PDA provided to residents + general instructions given on its use | Mixed/ survey |

Survey with quantitative and qualitative components (3 times) |

Decreased perceived value of the PDA at follow-up intervals. Responders felt that the PDA should be available at residency programs. But the integration of the PDA did not meet the anticipated expectations of overwhelming use by residents. | 33% |

| Kamadjeu 2005 |

Cameroon | EHR | Physicians and nurses/ 14 |

Urban primary care |

Comprehensive implementation strategy: numerous meetings involving users and different stakeholders + training (3-day session) + new data flow added | Qualitative | Interviews and direct observation |

Users generally showed good acceptance of the system. Monitoring the use of the system at the early stages of implementation was important to ensure immediate response to users’ comment and requests. | 67% |

| Katz 2003 |

USA | Email (triage) |

Physicians and residents/ 89 (90.8%) |

2 university- affiliated primary care centers |

Access to a triage-based email system (with a nurse navigator) promoted to the patients of physicians in the intervention group | Quantitative/ RCT |

A self- administrated survey |

Intervention appeared to improve physicians’ perceptions of the role of e-mail in clinical communication. | 66% |

| Keshavjee 2001 |

Canada | EMR | Physicians/ 32 |

Community- based physicians’ offices (18 sites) |

Implementation of EHR in exchange of a monthly fee + extensive training + onsite technical and support + interactive session prior the implementation to discuss |

Mixed | Questionnaires and observation |

The success of implementation varied from site to site. Despite extensive training, professional practice management consultation and project case management, several physicians subsequently left the project. But their staff was successfully using the EMR |

50% |

| Koivunen 2008 |

Finland | Internet- portal application for patient education |

Nurses/ 56 (63%) |

2 psychiatric hospitals |

Before implementation: evaluation of nurses’ IT skills and attitudes toward computers to tailor IT education. Implementation: portal presented to administrative personnel + manual compiled for users + information sessions + practical and technical support | Qualitative | Questionnaire with 2 open-ended questions |

The specific challenges are to ensure adequate technological resources and that the staff is motivated to use computers. Adequate individual time for the patient together with the nurse is a prerequisite for the successful implementation of the patient education portal. | 100% |

| Kouri 2005 |

Finland | Internet- based network services |

Midwives/5, public health nurses/2, physicians/3 |

Antenatal wards (1 university, 1 hospital, 2 clinics) |

Net Clinic’s introduction with managerial support and training. Different types of training linked to three groups based on their experiences (doubters, accepters and future confidents) | Qualitative | Semi- structured interviews |

Successful implementation of a comprehensive CPR that required substantial training and effort on the part of clinicians Managerial support, such as allocation of time and equipment was extremely important during the introductory phase. | 100% |

| Lai 2006 | USA | CDSS | Physicians/5 (preliminary), residents/16 (main study) |

Internal medicine |

Development of a tutorial designed to address barriers to use | Mixed/RCT and qualitative |

Interviews | Clinicians using the tutorial reported greater understanding of how to use the instrument appropriately. Many of the identified barriers to acceptance and use involved factors that could be addressed through training. | 83% |

| Lapinsky 2004 |

Canada | PDA | Physicians/ 17 (13 for focus group) |

4 community hospital intensive care units |

Distribution of handled devices + 1-hour training session + access to support by phone and email | Mixed/ prospective interventional study |

Focus group (for barriers and facilitators) |

Acceptance was variable (just over half of the participants using their handheld devices to access information on a regular basis). It may be improved by enhanced training and newer technological innovation. | 75% |

| Lapointe 2006 |

Canada | CIS | Physicians/15, nurses/14, system implementers/14 |

1 community and 2 university hospitals |

Support to physician and redesign of IS by implementers | Qualitative/ cross-case study |

Interviews, observation, document analysis |

Level of resistance varied during implementation, and in 2 instances had led to major disruptions and system withdrawals. Antagonistic responses from implementers to users’ resistances behaviours have reinforced these behaviours. |

83% |

| Larcher 2003 |

Italy | 1) Telemedicine 2) CPR |

Physicians and nurses/ 57 (post) (70%) |

5 general hospitals |

Training before the validation phase of the teleconsultation + EPR development in strong collaboration with the users | Mixed/ surveys |

Questionnaires before and after validation phase |

Positive attitude regarding the future use of the system in clinical field. Major difficulties encountered were in the introduction of the system into the daily routine. | 67% |

| Lee 2009, Lee 2008a, Lee 2008b |

Taiwan | Nursing information system (NIS) |

Nurses/623: 71% (survey), 24 (interviews) |

Medical center with 4 hospitals in different areas |

Pilot test of the NIS during the design phase. Early stage of implementation: nurses were required to chart nursing documentation of at least one patient on their shift both on the computer and on paper. | Mixed/ multimethod evaluation |

Questionnaire, focus group, interviews and work sampling observation |

After 2 years of NIS use, the nurses generally had a positive view of its value. Concerns remain about hardware devices, response time, content design, user support, workflow change and personal interaction with physicians and patients. When using the NIS in daily practice, nurses spent more time on documentation than on direct care, indirect care, and unit-related care. | 83% |

| Lee 2006a | Taiwan | PDA | Nurse managers/16 |

Inpatients units in a medical center |

Involved superusers in training + encouraging hands-on practice in addition to classroom teaching. | Qualitative/ descriptive, exploratory |

In-depth interviews |

In addition to training strategies, improving PDA features, involving end users in the content design phase, and ensuring interdisciplinary cooperation are vital elements for a successful adoption. | 83% |

| Lee 2006b | Taiwan | PDA | Nurses/15 | Hospital | Nurses were required to use the PDA systems | Qualitative/ descriptive, exploratory |

In-depth interviews |

Nurses went through different change stages: initially resisted using the PDA, but finally adopted it in their daily practice. The adoption process could be shortened by an anticipatory stage to refine the PDA system for use. |

83% |

| Leon 2007 | USA | Smart phones and CIRT (online database) |

Residents/31 | Community teaching hospital |

Special lectures, training sessions and group workshops on the use of the smart phones and Medline + one to one training provided by resident in charge of the project | Quantitative/ initial survey and prospective interventional cohort study |

Questionnaire | Physicians found these devices easy to use and the information retrieved useful. Proper training, technical support, familiarity with the technology, and presence of team leaders enhance the adoption of the tool. | 67% |

| Likourezos 2004 |

USA | EMR | Physicians and nurses/44 (38%) |

Large urban teaching hospital |

Training tailored on the functionality of users + regular sessions + adaptation of some workflow processes in response to staff or managerial concerns | Quantitative/ cross sectional survey |

Questionnaire | Participants favour the use of an EMR despite current concerns about its effect and impact. Nurses reported greater satisfaction in assistance with their tasks, whereas physicians reported minimal change. | 100% |

| Magrabi 2007 |

Australia | CIRT (online databases) |

Physicians/227 | General practice |

Use of an online evidence system in practice + online tutorial (for all) + RTC: advanced online training (for intervention group) | Quantitative/ experimental and observational components |

Pre and post-trial surveys |

GPs use of online evidence was directly related to their reported experiences of improvements in patient care. Post-trial clinicians positively changed their views about having time to search for information and pursued more questions during clinic hours. | 67% |

| Marcy 2008 |

USA | CDSS | Physicians/NS | Primary care ambulatory clinics |

Based on prior survey of physicians and clinic managers: development of a prototype CDSS + validation with an expert panel + usability testing physicians + iterative design changes based on their feedback + field tests | Qualitative/ iterative ethnographic process |

Interviews and observations |

During field tests, physicians incorporated the CDSS prototype into their workflow. Successful integration of ICT into clinical practice requires collaborative development of these systems with physicians, patients and support staff. | 83% |

| Martinez 2007 |

USA | Computer and Internet |

Physicians, managers, nurses/9 |

Community health centers |

A program provided computers for staff and patients (each center) + access to MD Consult database and a Web program + many workshops and classes + biweekly visits to support training |

Qualitative/ post test study design |

Interviews | Participants recommended improving the program by: increasing sensitivity to cultural issues; identifying and supporting a champion at each center to lead the project; allocating additional resources. |

100% |

| May 2001 | UK | Telemedicine | Clinicians, technician experts, managers/15 |

General practice and community mental health team |

GPs were invited to use the system to refer some patients to the community mental health team (CMHT) – no compulsion to use the system but it did offer speedier access to the CMHT | Qualitative/ ethnographic |

Interviews and observation |

Participants were initially enthusiasm about the potential of the technology; after 6 months of access, they found it problematic and ultimately, they rejected it. The main barrier was system’s incompatibility with the set of practices involved in consultations. | 83% |

| McAlearny 2005 |

USA | PDA | Physicians and organisational informants/161 |

7 sites (not defined) |

Active support for broad-based use (investments in material infrastructure, training, etc.) + active support for niche use (pursue of targeted application projects) + basic support for individual physician users | Qualitative/ organisational case studies |

Interviews and focus groups |

Individualised attention to existing physician users, improving usability and usefulness, promoting ICT and device use, and providing training and support would facilitate physician PDA adoption. | 67% |

| Newton 1995 |

UK | CIS (computerised care planning system) |

Nurses/139 | Hospital | 3 phases implementation: initially managed by external consultants and vendors; then by a care planning task group; gradually relegated to the hospital which became responsible for providing technical support services | Mixed/ survey and case study |

Questionnaires, interviews, observations: before, 3 months and 1 year after implementation |

A majority of nurses were ambivalent before the implementation; 3 months after, they held negative attitudes; 1 year after, attitudes showed a significant shift towards positive. The quality of care planning also improved significantly on the wards for which comparisons were possible. | 58% |

| O’Connell 2004 |

USA | EHR | Residents/ 95 (99%) |

Hospital (internal medicine and paediatrics) |

Prior the EHR system deployment, 2 groups of residents met the team of IT implementers to design templates for a variety of visit types |

Quantitative/ cross- sectional survey |

Questionnaire- based survey (elaborated from structured interviews) |

Differences in satisfaction between the 2 groups. Previous experience may have influenced the results (experience with a different EHR, with structured data entry prior the implementation, etc.). Organisational support did not appear to play an important role in differentiating satisfaction. |

100% |

| Ovretveit 2007 |

Sweden | EMR | Senior clinicians, managers, project team members, doctors et nurses/30 |

Large teaching hospital |

Consultation before implementation: consensus about need for the system and which one was best + prioritisation and diving by management team + competent IT project leader and team + tested, user-friendly and intuitive system needing little training | Qualitative/ prospective and concurrent study |

Interviews during implementation and 3 months after |

Implementation successful, on time and within budget. Importance of organisational, leadership and cultural factors, as well as a user-friendly EMR, which assists clinical work, is easily modified and which saves time and increases productivity. | 83% |

| Pagliari 2003 |

UK | Internet (Web-based resource) |

GP, nurses, administrators: questionnaires/ 26 (65%); interviews/9 |

Local health care cooperative comprising 5 GP surgeries |

User involvement in the early stage of development (testing process) of the web-based resources | Mixed | Questionnaire, interviews, observation and electronic feedback |

Evaluation informed important and unforeseen improvements to the prototype and helped refine the implementation plan. Engagement in the process of evaluation has led to high levels of stakeholder ownership and widespread implementation. | 75% |

| Paré 2006 | Canada | CPOE | Physicians/ 91 (72.5%) |

13 medical clinics network + hospital + private laboratory firm |

Introduction to the COPE system: use was not mandatory + in each site, a project champion to test the system and to play role of experts in the configuration of the system and of super users when system introduced | Quantitative | A mail survey |

Psychological ownership is positively associated with physicians’ perceptions of system utility and system user friendliness. Through their active involvement, physicians feel they have greater influence on the development process, and develop feelings of ownership toward the clinical system. | 100% |

| Popernack 2006 |

USA | CPOE | Nurses/ 81 (33%) |

Academic, tertiary care trauma center |

Involvement of nurses from the beginning of the system selection until implementation of the CIS + training + utilisation of superusers in training | Mixed | Survey (with open questions) |

Successful inpatient implementation of the fully integrated system. | 75% |

| Pourasghar 2008 |

Iran | EMR | Physicians/10, Nurses/10 |

University hospital |

The software was developed and tailored for the hospital. All staffs were trained to use the EMR system. Data were entered at different levels and by different persons |

Qualitative | Semi- structured interviews |

The quality of documentation was improved in areas where nurses were involved, but parts which needed physicians’ involvement were worse. Different factors involved: low physician acceptance of the EMR, lack of supervision and continuous training, high workloads, shortage of hardware, and software characteristics. |

67% |

| Puffer 2007 |

USA | EMR | Physicians/101 | Academic with medical and surgical specialties |

Redesign of the system by participation of users: implication of a team including physician and administrative leadership in a study that was undertaken to enhance the system | Qualitative/ ethnographic research |

Direct observation, feedback, focus group |

The study demonstrated a commitment to improving physicians’ efficiency when using the EMR. Managing physicians’ expectations for resolution of issues identified was an important success factor. | 100% |

| Pugh 1994 |

Canada | CIRT (computerized databases) |

Physicians/13 | Emergency of university hospital (2 sites) |

Initial training of up to 2 h. | Quantitative | Questionnaire (10 months after) |

Database searching was found easy-to learn. Positive notes included ease-of-use, accuracy of data, and accessibility of system and value of output. Negative notes: lack of integration with other systems, lack of system completeness, and a high subscription cost. | 67% |

| Rahimi 2009 |

Sweden | CPOE | Nurses/ 134 (67%), Physicians/ 176 (24%) |

Primary health care centers and hospitals |

Pilot project and gradual implementation by regional districts; introduction was mandatory; exceptions made for some clinics | Quantitative | Online questionnaire |

More nurses than physicians stated that the CPOE worked well in their clinical setting. More physicians than nurses found the system not adapted to their specific professional practice. |

67% |

| Ranson 2007 |

USA | PDA | Physicians/10 | Primary care and specialised clinics |

PDA given without charge + individualised training in the use of the programs and the PDAs (ranged from 1.5 to 4 h) |

Qualitative/ case study |

Questionnaire + interviews and observation |

Use of the PDA was associated with the value of information in clinical decisions of the individual user. | 100% |

| Rousseau 2003 |

England | CDSS | Physicians/8, nurses/3, practice managers/2 |

5 general practices |

Introduction of guidelines into general practice clinical computer systems; one day training workshop for 2 members from each practice. | Qualitative/ longitudinal study |

Interviews and feedbacks |

Clinicians did not adopt the CDSS: they found it difficult to use and did not perceive it to bring benefits for practice. Key issues: relevance and accuracy of messages, flexibility to respond to other factors influencing decision making in primary care. |

100 % |

| Sicotte 1998 |

Canada | CPR | Physicians/21 and project teams/10 |

4 hospitals | Implementation of a large CPR in medical work with a project team involving mainly nurses | Qualitative | Interviews, focus group, observations, document analysis |

Physicians had a great reluctance to using the system: lack of synchronization between the care and information processes. Several dimensions were not properly taken into account when designing and developing the CPR. | 83% |

| Smordal 2003 |

Norway | PDA | Medical students/NS |

Different practical settings |

Mix of activities. A team of medical students work as IT-support (or superusers). | Qualitative | Interviews, participant observation |

The medical students did not use the PDA for information gathering. PDAs should be regarded as potential gateways. | 67 % |

| Soar 1993 |

Australia | HIS | Physician/ NS (36%) |

A 700-bed teaching hospital |

Doctors are encouraged to directly use HIS by many means: strong executive support, training, firm policies that other staff would not use systems on behalf of them, on-line bulletin. | Mixed | Survey and structured interviews |

First successful implementation of direct doctor use of HIS in an Australian hospital (system in use for 3 years). | 50% |

| Terry 2009 |

Canada | EMR | Physicians/13, other health professionals/ 11, administrative staff/6) |

6 family practice sites |

Installation of equipment and training of the participants. | Qualitative | Semi- structured interviews |

Importance of being aware of factors that influence implementation and adoption: computer literacy, dedicated time for EMR implementation and adoption, training activities, supporting problem-solvers in the practice. |

100% |

| Thoman 2001 |

USA | CIS (point-of-care technology) |

Pilot group of nurses/6 |

Home care | A full 12-week training curriculum (including 9 days classroom time and 3 weeks of supervised field experiences). |

Qualitative | Focus group | 4 rules for the training: continually involve end-users with a “users group”, expect a learning curve for everyone, allow for varying degrees of resistance, and reinforce future benefits during the transition. | 67% |

| Topps 2003 |

Canada | PDA | Physicians/ 24 (92%) quest; 16 (62%) focus groups |

Department of family medicine |

Introduction of the PDA individually in a short personal session with one expert user + technical support + shared-cost purchasing (30% paid by participant). | Mixed | Structured questionnaire and focus group |

With the right support structures faculty adopt PDAs in clinical and teaching settings. The faculty support group and the cost-sharing arrangement leading to ownership have contributed to adoption. | 75% |

| Toth-Pal 2008 |

Sweden | CDSS | Physicians/5 | A primary health care center |

Introductory demonstration of the CDSS (1,5 h) + access to the program + individual training session (CDSS applied to the medical records of own physicians’ patients) + encouragement to use the program in the every day clinical work. | Qualitative | Interviews (after the training and follow-up) + observation |

Implementation of the CDSS is not successful: its actual usage remained very limited. Different profiles associated with the degree of acceptance of the CDSS. Important contributing factors: GP’s individual computer skills and attitudes towards the computer’s functions in disease management and in decision-making. | 100% |

| Travers 1997 |

USA | HIS (emergency department clinical system) |

Various (nurses, physicians, clerical staff)/NS |

Hospital emergency department |

Development of a HIS with end-user inputs + project team included members of staff at every level of development and implementation + comprehensive training plan and change strategies + regular communication | Quantitative | Questionnaire | The project team succeeded in designing a system to meet the clinical users’ needs. Key to success: the integral involvement of ED staff in the development of the system, commitment of the necessary resources, and top-level administrative support. | 33% |

| Trivedi 2009 |

USA | CDSS | Physicians/13, advanced nurse practitioners /2 |

Public mental health clinics (5 sites) |

Field testing of feasibility of implementation of CDSS in 5 sites: training of physicians about the guideline and the use of CDSS (4 h) + written instruction manual + IT support on site initially and later by phone + training sessions for directors and managers to suggest solutions to potential workflow transition issues + feedback from clinicians |

Qualitative | Informal feedback |

Issues regarding computer literacy and hardware/software requirements were identified as initial barriers. Concerns about negative impact on workflow and potential need for duplication during the transition from paper to electronic systems. Importance of taking account organizational factors when planning implementation of a CDSS. | 50% |

| Tuominen 1996 |

USA | Internet | Physicians/18 | 13 family practice clinics |

Introduction to Internet through seminars (13 to 30 min each) that included examples of searches on the web with searches graded for physician usefulness | Quantitative | Questionnaire | Health care professionals recognise the practical usefulness of the Web. But the real challenge is to convince those who are not computer literate to invest time in training. | 33% |

| Vanmeerbeek 2004 |

Belgium | EMR | Various (doctors, nurses and others)/57 for nominal group |

Eight primary care medical houses |

A 2 h workplace meeting to assess indicators of current use of EMR and to define the content of an action program for removing resistances with users’ participation | Mixed | Quantitative measures of use and nominal group |

The use of EMR remained slight. Practitioners are willing to computerize if: they get immediate advantages, the tool is easy to use, not time-consuming, it respects the specificity of work and organization (interdisciplinary and self-managed teams), there is external support (training, supervision) | 75% |

| Verhoeven 2009 |

Netherlands and Germany |

CIRT (online guidelines) |

Nursing assistants, nurses, physicians, and medical microbiologists/20 |

Hospitals/ 2 Dutch and 2 German |

User-centered design process including physicians, nurses and nursing assistants to gather their opinion toward the website and to generate a sense of involvement | Qualitative | Interviews with open ended questions |

Involvement of potential adopters in the development and implementation process is very important. The website’s credibility is an important additional requirement. Training and feedback appear to reinforce imitation and maintenance of technology adoption. | 83% |

| Verwey 2008 |

Netherlands | Electronic nursing record |

Nurses/6, manager/1, members of the project group/2 |

Large regional hospital |

Training of key users + ENR council responsible (with the project group) for the management, maintenance and updating of the system + training for all nurses (4 meetings of 2.5 h) + extra staffing scheduled |

Qualitative | Participatory observation, document analyses, interviews. |

Involvement of the nursing staff in the whole process promoted acceptance of the system. However, the ENR did not produce the benefits expected. Lack of time gains proved to be a major barrier to the acceptance of the system. | 83% |

| Vishwanath 2009a Vishwanath 2009b |

USA | PDA | Clinicians/ 244 in pre-survey, 80 in post-survey, 59 completed both |

Academic tertiary care children hospital |

2 phases of implementation: 1) pre-participation surveys + small-group training sessions + orientation. 2) distribution of PDA and participation in a series of patient safety initiatives | Quantitative | Web-based survey (pre and post- intervention, 12–14 months apart. |

Early adopting physicians are younger and junior in experience and status, and are more likely to be aware of and own news technologies than later adopting physicians. The top barrier to PDA adoption among early adopters is cost, while for later adopters it is training. | 67% |

| Walji 2009 |

USA | EPR | Implementation team/4, faculty, residents and staff/pre: 78 (11%) and post: 138 (20%) |

University Health Science Center |

Extensive planning phase including in-depth discussions among faculty and staff, market research and visits to other schools + EPR installation with additional IT employee + workflow defined + pilot testing + stakeholders and users engaged throughout the project’s life cycle | Mixed | Interviews, document analyses, 2 surveys (before and after) |

Users had mixed feelings about the EPR in terms of efficiency and time required compared with paper charts. Many users felt that the EPR improved legibility and access to a patient chart. However, only 29% though the EPR improved productivity. | 67% |

| Walter 2000 |

Australia | Computer | Various/ 309 (80%) survey; 212 (77%) follow up |

Various (urban mental health system) |

Introduction of computers and implementation of computer training (through in-service programmes) | Quantitative/ observational |

Questionnaire (before and 6 months after introduction) |

Most respondents, especially those with computer experience or who had worked in mental health for less than 5 years, viewed computers favourably. | 100% |

| Watkins 1999 |

UK | PACS | Key users from clinical and radiological staff/34 |

Hospital | 2 trainers undertook a formal training program targeting all staff + 1/3 of each department became core trainers, and an “in-house” trainer provided training on a more flexible basis | Qualitative | Semi- structured interviews |

Overall, users appeared to be satisfied with PACS. All staff said that they preferred PACS to the previous, conventional radiology service. | 83% |

| West 2004 |

Scotland | CIS | Physicians, nurses and administrative staff/33 |

Remote rural primary health care |

The project provided: data operator, inputs data to the computer system recorded on a paper, access to ongoing training, technical help line, and quality assurance processes |

Qualitative | Interviews | Remote rural primary care presents a number of organisational features that require understanding for the implementation of initiatives developed in an urban working environment: primary care teams tend to be smaller, characterised by flexibility, experience less support from other services and provide care in a wider range of situations and settings. |

83% |

| Whittaker 2009 |

USA | EHR | Nurses/11 | Rural hospital |

Training classes: 1-day (8 h) introduction and training + an additional 4-hour refresher class (after a 6-month delay) | Qualitative | Interviews | Personal, computer-related and contextual characteristics facilitated and acted as barriers to the acceptance and use of a computerised EHR system. | 100% |

| Whitten 2004, Whitten 2000 |

USA | Telemedicine | Clinical providers, technical and support staff, administrators/ 25 (focus groups) + 36 (interviews) |

A clinic, a crisis centre, a youth detention centre and patients homes |

Telepsychiatry project in 4 phases: formalised training programs for each phase + project handbooks and supplementary materials provided | Qualitative (for providers) |

Interviews and 4 focus groups |

Telemedicine usage varied across the 4 project phases. Variation could be explained by: provider roles, organisational strategic goals and resources, inherent organisational culture, leadership and managerial factors. | 67% |

| Wibe 2006 |

Norway | EHR | Head nurses and key persons/22 |

University hospital |

Step-wise implementation strategy: introduction to computers and to EPR to all staff, training of 2–3 key persons in each unit | Quantitative | Questionnaire | On-site training by colleagues, using computers on the ward, and documenting admitted patients who received care and treatment were identified as the most important success factors in the implementation process. | 33% |

| Wilson 1998 |

USA | Computer (wireless, pen-based computing) |

Nurses/16 | Home health nursing |

Nurses used the computer for patient admissions process during a 10 week period + 3 ½ day training sessions | Qualitative | Focus groups (before and after 10 weeks) |

Nurses agreed that they had been well prepared for computers. They did not want to return to paper. | 83% |

| Yeh 2009 | Taiwan (China) |

Nursing Process Support System (NPSSC) |

Nurses/27 | 5 nursing homes |

Task force (consisted of nurses, physicians, computer programmers, administrators) formed to develop the NPSSC + workplace training for nurses (3 h/week for 6 weeks) + one-on-one hands-on consultation on how to use the Internet to navigate the NPSSC |

Mixed/quasi- experimental design and observation |

Questionnaire and observation |

NPSCC significantly improved nursing documentation and participants reported an increased satisfaction with nursing documentation. |

50% |

| Zheng 2005 |

USA | Clinical reminder system |

Residents/41 | Ambulatory primary care clinic in urban teaching hospital |

Individual training provided to all users of the clinical reminder system. Use of the system was recommended but not mandatory | Mixed/ longitudinal and qualitative study |

Structured interviews, surveys, on-site observation, and textual notes |

A large proportion of users demonstrated a consistently low or decreasing level or usage over time. The lessons learned and experiences gained have helped system designers to re-engineer the reminder system. | 83% |

CDSS Computer-based Decision Support System

CIRT Clinical Information Retrieval Technology

CIS Clinical Information System

CPOE Computerized Physician Order Entry

CPR Computer-based Patient Record

EHR Electronic Health Record

EMR Electronic Medical Records

HIS Hospital Information System

PACS Picture archiving and communication system

PDA Personal Digital Assistant

RR response rate

Synthesis

A narrative synthesis was performed to summarize the evidence. Narrative synthesis is the process of synthesising primary studies to explore heterogeneity descriptively rather than statistically [22]. This type of synthesis provides an overall picture of current knowledge that can inform policy and practice decisions in relation to a particular topic [23].

Results

Description of the studies

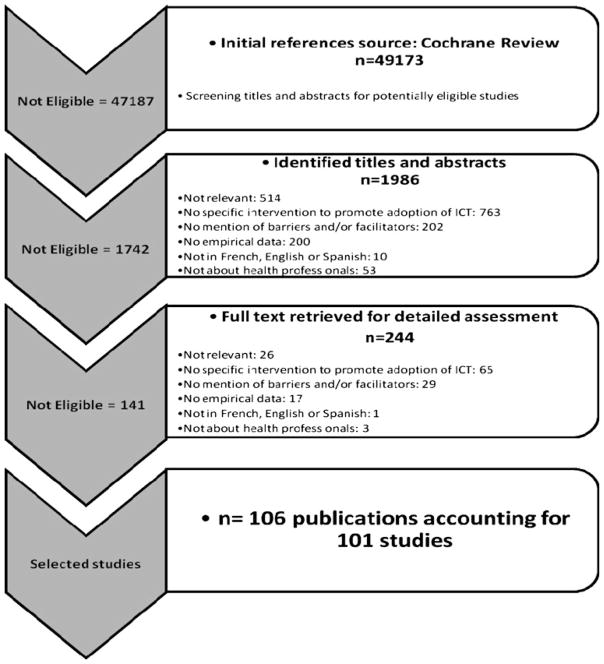

A total of 1,986 titles and/or abstracts from the Cochrane review database were assessed for eligibility; 244 articles were retained for detailed evaluation. Of these, 141 studies were excluded from the review because they did not meet inclusion criteria. One hundred and six (106) articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the review, with four studies reported in two (or three for one of them) distinct articles. The review therefore included 101 studies. [6, 24–123]. The study selection flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study selection flow diagram

The characteristics of included studies are summarised in Appendix 1. The types of ICT covered were: Electronic Medical or Health Records (EMR/EHR) or Clinical Patient Records (CPR) (n=23); Clinical Information Retrieval Technology (CIRT) (online databases, digital libraries, online guidelines) and computers (n= 21); Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs or handheld devices) (n=13); Hospital, clinical and nursing information systems (HIS, CIS, NIS) (n=10); Computer-based Decision Support Systems (CDSS) (n=8); Computerised Provider Order Entry systems (CPOE) (n=5); Telemedicine and Telehealth (n=5); e-learning (n=4); Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS) (n=2); e-prescribing (n=2); Point-of-care computing (POC) (n=2); others (laboratory reporting system, clinical reminder system, email between provider and patient, Internet portal for patient education, Internet-based network services, smart phones) (n=6).

In most cases, the setting of care was a hospital. Participants were physicians (including residents) in 38 studies (37%); nurses in 17 studies (17%); mixed clinical staff (physicians, nurses, and others such as pharmacists) in 25 studies (25%); and clinical but also clerical staff, managers or members of the implementation project in 21 studies (21%). More than half of the studies (n=53; 52%) took place in North America, 40 in the United States (40%) and 13 in Canada (13%). A number of studies were from the UK (n=11; 11%), 8 studies were from Australia, 4 from Sweden, 3 from Netherlands, and 3 from Denmark. 72 studies (71%) have been published since 2003, and 21 (21%) during the last two years.

Forty-nine studies (48%) had a qualitative research approach, using one or more of the following methods for data collection: interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. Twenty-seven studies (27%) used a quantitative research approach, but only 4 of them were randomised clinical trials. Other quantitative studies were most frequently cross-sectional surveys. Twenty-five studies (25%) used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. Interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires with open and closed questions were the methods used for data collection in these studies.

Most studies were of good or moderate methodological quality (mean scores of 81% for qualitative studies, 77% for quantitative studies, and 67% for mixed methods studies). This score was calculated by dividing the number of positive responses by the number of “relevant criteria” × 100. The number of criteria was 5 for qualitative studies, 3 for experimental or observational quantitative studies, and 12 for mixed studies [14] (see Appendix 2).

Appendix 2.

A scoring system for mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews (Pluye et al 2009)

| Qualitative studies and qualitative components of mixed methods studies: | |

| (1) Qualitative objective or question | _____ |

| (2) Appropriate qualitative approach or design or method | _____ |

| (3) Description of the context | _____ |

| (4) Description of participants and justification of sampling | _____ |

| (5) Description of qualitative data collection and analysis | _____ |

| (6) Discussion of researchers’ reflexivity | _____ |

| Quantitative experimental studies, and quantitative experimental components of mixed methods studies: | |

| (1) Appropriate sequence generation and/or randomization | _____ |

| (2) Allocation concealment and/or blinding | _____ |

| (3) Complete outcome data and/or low withdrawal/drop-out | _____ |

| Quantitative observational studies, and quantitative observational components of mixed methods studies: | |

| (1) Appropriate sampling and sample | _____ |

| (2) Justification of measurements (validity and standards) | _____ |

| (3) Control of confounding variables | _____ |

| Overall mixed methods approach of selected mixed methods studies: | |

| (1) Justification of the mixed methods design | _____ |

| (2) Combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection-analysis techniques or procedures | _____ |

| (3) Integration of qualitative and quantitative data or results | _____ |

| Total score in percent | _____ |

The presence/absence of criteria (yes/no) may be scored 1 and 0, respectively. Then, a ‘quality score’ can be calculated as a percentage: [(number of ‘yes’ responses divided by the number of ‘appropriate criteria’) × 100]. For example, studies with good qualitative and quantitative observational components plus good overall mixed methods approach may be scored 100%: [(6 + 3 + 3)/12] × 100 (Pluye 2009)

Most of the included studies described interventions in the context of an implementation or an attempt to introduce a specific ICT. Many different types of intervention were used. The most common was training, but this intervention varied from general instructions to intensive training sessions of different time lengths. Training could be one-to-one [28, 53, 84, 98, 105, 106, 123], tailored to users’ needs [49, 57, 72, 74, 82], or in group workshops [31, 41, 42, 52, 69, 81, 85, 104, 113]. In some studies, training was given to superusers who could then train others [63, 79, 93, 99, 116, 120]. The involvement of superusers was described in many studies. Many interventions focused on the participation of clinicians (or superusers) in the development of the ICT [32, 40, 43, 44, 91–93, 107, 112], and/or in the implementation plan [6, 37, 63, 69, 79, 92, 93, 107]. Recent studies particularly reported the development of an ICT on the basis of a user-centred design [36, 50, 55, 83, 90, 111]. Three studies included an economic intervention combined with other interventions [62, 66, 105]. Finally, many studies and particularly the more recent, described a multifaceted intervention where a mix of strategies such as training, support, and involvement of users was used to introduce the ICT. In the same way, some studies reported an implementation designed following an unsuccessful previous implementation process [33] or that attempts to address some of the barriers of the adoption or use of a ICT [56].

Adoption factors

The final categorisation of adoption factors is presented in Table 1 (see the grid in Appendix 3). Globally, various types of factors (technological, human, and organisational) influenced the success or failure of ICT implementation. Factors facilitating ICT adoption tended to be mostly related to the perception of the characteristics of the specific ICT application and to organisational aspects. Barriers were related to ICT characteristics too, but were also found at the individual, professional, and organisational levels. Some of the adoption factors identified were ‘multilevel’ since they could affect more than one level (e.g. ease of use can be seen as a characteristic of the ICT but is also related to familiarity with ICT at the individual level), and they were described as a facilitator by some and as a barrier by others.

Table 1.

Factors related to the success or failure of ICT adoption*

| Factors | Facilitators (F): (N of Studies) | Barriers (B): (N of Studies) | F and B: (N of Studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors related to ICT | |||

| ➢ Design and technical concerns | 4** [34, 54, 90, 111] | 31 [6, 26, 29, 30, 32, 35, 39, 40, 52, 56, 59, 61, 62, 65, 75, 78–80, 86, 95, 98–101, 106, 113, 118, 119, 121–123] | 7 [50, 81, 83, 91, 94, 102, 110] |

| ➢ Characteristics of the innovation | |||

| • Perceived usefulness (or relative advantage) | 43 [26, 30, 32, 34, 38, 44, 46, 49, 53–55, 57, 58, 62, 63, 65, 67, 69, 71, 73, 77, 81, 83–85, 87, 89–94, 102, 104, 105, 109, 110, 113, 115, 116, 118, 121, 123] | 17 [6, 28, 29, 31, 37, 39, 61, 66, 70, 72, 96, 97, 99–101, 106, 117] | 5 [45, 82, 86, 98, 111] |

| • Compatibility (with work process...) | 11 [32, 44, 50, 53, 55, 58, 81, 90, 91, 102, 114] | 20 [6, 24, 33, 35, 39, 40, 51, 56, 72, 77, 86, 95, 97, 99, 100, 106, 108, 111, 117, 120] | 1 [89] |

| • Ease of use/complexity | 23 [26, 32, 34, 44, 50, 53, 55, 58, 60, 73, 81, 82, 90–92, 94, 96, 102, 110, 111, 113, 118, 123] | 9 [24, 29, 39, 48, 97, 99, 104, 109, 120] | 1 [116] |

| • Triability | 2 [47, 90] | 1 [40] | – |

| • Observability | 3 [50, 55, 90] | – | 1 [110] |

| ➢ System reliability | 5 [34, 44, 55, 65, 73] | 5 [50, 66, 75, 97, 121] | – |

| ➢ Interoperability | 3 [46, 90, 103] | 9 [29, 40, 52, 59, 91, 96, 101, 108, 123] | – |

| ➢ Legal issues | |||

| • Confidentiality – privacy concerns | 4 [73, 80, 82, 110] | 5 [26, 30, 59, 62, 87] | – |

| • Other legal issues –security related concerns | 2 [30, 110] | 3 [74, 87, 113] | – |

| ➢ Validity of the resources | 2 [58, 84] | 6 [39, 51, 74, 91, 106, 111] | – |

| • Scientific quality of the information resources | 4 [26, 43, 58, 96] | 6 [43, 48, 74, 79, 97, 98] | – |

| • Content available (completeness) | – | 4 [28, 94, 96, 98] | 1 [43] |

| • Appropriate for users (relevance) | 4 [28, 58, 84, 94] | 8 [40, 51, 72, 96, 98–100, 123] | – |

| ➢ Cost issues | 1 [105] | 10 [6, 36, 59, 66, 81, 87, 90, 96, 113, 114] | – |

| Individual factors or healthcare professional characteristics | |||

| ➢ Knowledge | |||

| • Awareness of the existence and/or objectives of the ICT | 2 [31, 64] | 7 [29, 33, 73, 74, 85, 112, 115] | 2 [45, 113] |

| • Familiarity with ICT | 10 [31, 33, 64, 65, 80, 89, 91, 104, 111, 119] | 31 [24, 27, 29, 34, 38, 39, 41, 42, 48, 52, 54, 57, 59, 62, 67, 72–75, 78, 81, 87, 93, 95, 99, 103, 106, 108, 109, 116, 122] | 6 [45, 58, 112, 113, 115, 118] |

| ➢ Attitude | |||

| • Agreement with the particular ICT (general attitude) | 12 [53, 54, 60, 62, 68, 78, 81, 89, 104, 115, 119, 121] | 2 [6, 85] | 1 [114] |

| • Agreement with ICTs in general (welcoming/resistant) | 1 [45] | 1 [72] | 2 [111, 133] |

| • Applicability to the clinical situation (including practical) | 3 [53, 77, 89] | 7 [34, 88, 96, 97, 99, 100, 106] | – |

| • Confidence in the ICT developer | – | 3 [51, 52, 74] | – |

| • Challenge to autonomy | – | 3 [51, 100, 108] | 1[58] |

| • Impact on clinical uncertainty | 2 [53, 58] | 1 [37] | – |

| • Time saving/time consuming or increased workload | 11 [28, 34, 36, 44, 46, 58, 60, 65, 81, 111, 121] | 30 [24, 27, 29, 30, 37, 39, 40, 48, 49, 56, 59, 61, 62, 71, 73, 78, 80, 88, 96, 97, 99, 100, 104, 106, 109, 111, 112, 114, 117, 123] | 2 [57, 82] |

| • Motivation to use the ICT (readiness)/resistance to change | 3 [55, 111, 121] | 15 [30, 33, 38, 51, 59, 66, 72, 73, 91, 94, 101, 106, 112, 115, 119] | 2 [57, 113] |

| • Self-efficacy (believes in one’s competence to use the ICT | – | 4 [42, 54, 116, 122] | – |

| • Impact on professional security | – | 5 [53, 54, 61, 80, 93] | – |

| ➢ Socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, experience, other) | 2 [84, 115] | 2 [73, 98] | 3 [25, 58, 133] |

| Human environment | |||

| ➢ Factors associated with patients | |||

| • Patients’ attitudes and preferences regarding ICT | 3 [32, 108, 119] | 4 [54, 70, 72, 73] | – |

| • Patient/health professional interaction | 1 [72] | 11 [27, 37, 45, 55, 77, 78, 86, 88, 93, 106, 123] | – |

| • Applicability to patients’ characteristics | 1 [119] | 6 [32, 61, 70, 72, 85, 86] | 1 [36] |

| ➢ Factors associated with peers | |||

| • Attitude of colleagues towards ICT | – | 4 [6, 73, 74, 79] | 1 [57] |

| • Support and/or promotion of ICT by colleagues | 2 [43, 105] | 4 [6, 57, 85, 118] | – |

| • Relations between colleagues | 2 [111, 118] | ||

| Organisational environment | |||

| ➢ Factors associated with work | |||

| • Work structure (setting of care, salary status) | – | 4 [32, 72, 108, 117] | – |

| • Time constraints and workload | – | 28 [24, 27–29, 31, 34, 36, 41, 42, 52, 58, 59, 63, 68, 72, 77, 83, 91, 94, 103, 106, 111, 112, 114–117, 120] | – |

| • Work flexibility | 1 [80] | 3 [28, 52, 77] | – |

| • Relationship between professional groups (role boundaries, changes in tasks) | 1 [44] | 13 [31, 35, 40, 54, 73, 76, 78, 79, 93, 100, 106, 111, 117] | 1 [110] |

| • Professional culture | 1 [58] | 1 [90] | |

| ➢ Skills and staff | |||

| • Leadership | 7 [27, 43, 47, 63, 90, 93, 114] | 2 [33, 119] | – |

| • Staff issues (stability, shortage) | 1 [36] | ||

| ➢ Resource availability | |||

| • Resources available (additional) | 7 [30, 60, 65, 67, 96, 102, 105] | 2[90, 114] | 1 [47] |

| • Material resources (access to ICT) | 19 [32, 38, 40, 42, 48, 52, 58, 62, 69, 72, 78, 80, 87, 94, 111, 112, 115, 117, 122] | ||

| • Human resources (IT support) | 11 [47, 55, 65, 73, 87, 91, 93, 102, 104, 105, 121] | 9 [40, 45, 52, 78, 85, 108, 112, 113, 119] | – |

| ➢ Organisational factors | |||

| • Training/lack of or inadequate training | 19 [26, 31, 37, 42, 59, 60, 65, 71, 74, 83, 87, 93, 95, 104, 107, 111, 114, 120, 122] | 15 [6, 27, 29, 33, 48, 54, 56, 72, 73, 77, 80, 99, 103, 113, 116] | 7 [47, 58, 91, 102, 110, 112, 118] |

| • Presence and use of champions/absence of champions | 18 [32, 43, 58, 59, 63, 79, 80, 87, 90, 92, 93, 103, 105, 107, 111, 114, 118, 120] | 2 [6, 51] | – |

| • Management (strategic plan) | 13 [37, 58, 59, 69, 87, 90, 92, 102, 105, 107, 112, 114, 120] | 8 [27, 56, 85, 94, 100, 110, 116, 119] | 2 [45, 73] |

| • Participation of end-users in the design/Lack of participation | 14 [44, 55, 69, 73, 80, 83, 90–93, 95, 102, 107, 111] | 7 [27, 29, 35, 38, 78, 79, 100] | – |

| • Participation of end-users in the implementation strategy | 11 [43, 47, 63, 69, 71, 87, 90, 92, 93, 104, 107] | – | – |

| • Communication (included promotional activities) | 6 [59, 87, 91, 104, 107, 114] | 3 [33, 69, 85] | – |

| • Relationship between administration and health professionals | 1 [90] | 4 [33, 51, 79, 96] | 1 [76] |

| • Ongoing administrative or organisational support | 10 [58, 63, 71, 73, 76, 79, 80, 89, 92, 107] | 6 [38, 69, 73, 85, 108, 119] | – |

| • Incentive structures | 1 [57] | 1 [94] | |

| • Readiness | 1 [80] | 1 [27] | |

| • Other organisational or cultural aspects | 1 [112] | ||

| External environment | |||

| • Financing of ICT/financial support | 1 [72] | ||

| • Interorganisational relations | 3 [36, 112, 114] | – | |

A few factors found in one study only have not been cited here.

The number of studies that reported the factor acting as facilitator or barrier (or both) is in bold; and the specific studies are identified by their reference number (in brackets).

Appendix 3.

List of factors related to the success or failure of ICT adoption

| 1. Factors related to ICT | |

| 1.1 | Design and technical concerns |

| 1.2 | Characteristics of the innovation |

| 1.2.1 | Relative advantage (usefulness) |

| 1.2.2 | Compatibility (with work process, values) |

| 1.2.3 | Ease of use/complexity |

| 1.2.4 | Triability |

| 1.2.5 | Observability |

| 1.3 | System reliability |

| 1.4 | Interoperability |

| 1.5 | Legal issues |

| 1.5.1 | Confidentiality - privacy concerns |

| 1.5.2 | Other legal issues (including security) |

| 1.6 | Evidence regarding benefits of IT |

| 1.7 | Validity of the resources |

| 1.7.1 | Scientific quality of the information resources |

| 1.7.2 | Content available (completeness) |

| 1.7.3 | Appropriate for the users (relevance) |

| 1.8 | Cost issues |

| 1.9 | Environmental issues |

| 2. Individual factors or healthcare professional characteristics (knowledge and attitude) | |

| 2.1 | Knowledge |

| 2.1.1 | Awareness of the existence and/or objectives of the ICT |

| 2.1.2 | Familiarity with ICT |

| 2.1.3 | Familiarity with technologies in general |

| 2.2 | Attitude |

| 2.2.1 | Agreement with the particular ICT |

| 2.2.1.1 | Applicability to the clinical situation |

| 2.2.1.2 | Confidence in ICT developer |

| 2.2.1.3 | Challenge to autonomy |

| 2.2.1.4 | Impact on clinical uncertainty |

| 2.2.1.5 | Time consuming/time saving |

| 2.2.1.6 | Outcome expectancy (use of the ICT leads to desired outcome) |

| 2.2.1.7 | Motivation to use the ICT (readiness)/resistance to use the ICT |

| 2.2.1.8 | Self-efficacy (believes in one’s competence to use the ICT) |