Abstract

Ultrasound in the sub-megahertz range enhances thrombolysis and may be applied transcranially to ischemic stroke patients. The consistency of transcranial insonification needs to be evaluated. Acoustic and thermal simulations based on computed-tomography (CT) scans of 20 patients were performed. An unfocused 120-kHz transducer allowed homogeneous insonification of the thrombus, and positioning based on external landmarks performed similarly to an optimized placement based on CT data. With a weakly focused 500-kHz transducer, the landmark-based positioning underperformed. The predicted inter-patient variation of in situ acoustic pressure was similar with both transducers for the optimized placement (18.0–26.4% relative standard deviation). The simulated maximum acoustic pressure in intervening tissues was 2.6±0.6 and 2.0±0.7 times the pressure in the thrombus for the 120-kHz and 500-kHz transducers, respectively. A 1 W/cm2 insonification of the thrombus caused a 3.8±2.2°C temperature increase in the bone for the 120-kHz transducer, and a 13.4±3.3°C increase for the 500-kHz transducer. Contralateral local maxima up to 1.1 times the pressure amplitude in the targeted zone were predicted for the 120-kHz transducer. We established two transducer placement approaches, one based on analysis of a head CT and the other using simple external, visible landmarks. Both approaches allowed consistent insonification of the thrombus.

Keywords: Transcranial ultrasound, Thrombolysis, Acute ischemic stroke, Finite-difference simulation, Thermal simulation

Introduction

Accurate spatial targeting of highly focused ultrasound in the brain can be achieved transcranially using large helmet-type transducer arrays combined with registered computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance images (MRI) (Marquet et al., 2009; Marsac et al., 2012). This type of approach has promising applications (Monteith et al., 2013). When confined spatial targeting is less critical, simpler approaches have been proposed (Deffieux and Konofagou, 2010). In particular, ultrasound enhanced thrombolysis (UET) in acute ischemic stroke patients generally can be achieved with a mechanical index in the diagnostic range (Holland et al., 2011; Meairs et al., 2012). Therefore, weakly focused beams can be used to enhance thrombolysis without adverse effects in intervening tissues. Technologies, which enhance thrombolytic efficacy, would play a most important role in the management of vessel occlusions longer than 8 mm, because standard thrombolytic approaches are generally ineffective for these lesions (Riedel et al., 2011). Consequently, there is a particular interest in UET of large thrombi exceeding 8 mm in length. In order to accelerate the lysis of such large thrombi effectively, a device producing a relatively wide beam, enabling irradiation of the entire thrombus and allowing a simple positioning procedure is advantageous. Recent experience in patients with acute ischemic stroke has shown that length and location of thrombus can be assessed using non-contrast head CT (Riedel et al., 2011). Consequently, selection of patients for UET and related treatment planning can be done using non-contrast head CT alone. Non-contrast head CT images are usually acquired during standard ischemic stroke patient management and do not introduce any delays in care (Jauch et al., 2013). This aspect is critical because the probability of a good clinical outcome decreases rapidly as the time to reperfusion increases (Khatri et al., 2009).

Thrombolysis enhancement with 2-MHz ultrasound produced by transcranial Doppler (TCD) diagnostic devices has been demonstrated clinically (Alexandrov et al., 2004; Molina et al., 2006). The transducer is aligned with the middle cerebral artery (MCA) through the temporal bone using the Doppler signal from the persistent flow (Alexandrov et al., 2007). The acoustic pressure transmitted through the temporal bone varies from one patient to another (Ammi et al., 2008). In particular, about 18% of patients have a temporal bone with poor acoustic transmission causing inadequate signal for TCD examination (Wijnhoud et al., 2008), and potentially limited efficiency for UET. Barlinn et al. (2013) estimated the in situ acoustic pressure using a simple attenuation model based on CT data for 20 subjects in the transcranial ultrasound in clinical sonothrombolysis (TUCSON) trial. Although the number of patients was insufficient to reach statistically significance, the estimated in situ acoustic pressure tended to be higher for patients functionally independent at 3 months. Hence, some patients may receive an insufficient acoustic pressure for thrombolysis enhancement with TCD insonification. Frequencies in the sub-megahertz range allow efficient acoustic transmission through the skull (Ammi et al., 2008; Fry and Barger, 1978). Thus, more consistent insonification of the thrombus can be expected at frequencies lower than 2 MHz used for TCD.

The efficiency of UET in the sub-megahertz range have been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo (Behrens et al., 2001; Datta et al., 2006; Hitchcock et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2011; Saguchi et al., 2008; Wang Z. et al., 2008). However, the clinical applicability of low-frequency UET remains to be demonstrated. An increased rate of cerebral hemorrhages was reported at 300 kHz during the Transcranial Low-Frequency Ultrasound-Mediated Thrombolysis in Brain Ischemia (TRUMBI) clinical trial (Daffertshofer et al., 2005). A high pressure amplitude combined with constructive interference due to reflections from the contralateral bone likely caused strong local inertial cavitation that induced negative bioeffects (Baron et al., 2009; Wang Z. et al., 2008). Nevertheless, safe and efficient UET has been shown in small animal models (Ren et al., 2011; Saguchi et al., 2008). Ultrasound at 500 kHz with an amplitude that induced thrombolysis enhancement in small animals was also applied transcranially to primates without causing adverse effects (Shimizu et al., 2012). In order to use low-frequency UET in humans, the feasibility of consistently irradiating the thrombus with an acoustic pressure inducing efficient thrombolysis while minimizing collateral negative effects must be demonstrated. Inter-patient variation of bone properties and skull geometry is inherent in humans and not replicated in animal studies. Although the acoustic fields produced by low-frequency UET have been studied in vitro and by simulation (Ammi et al., 2008; Baron et al., 2009), their variation in a large number of stroke patients has not been assessed. Extensive characterization of the transcranial ultrasound fields in humans is necessary for the clinical testing of low-frequency UET.

The objective was to establish two transducer alignment strategies and to study the transcranial acoustic field obtained with two previously investigated low-frequency UET transducers. For this purpose, simulations based on twenty CT scans of ischemic stroke patients were conducted and the predicted ultrasound fields were evaluated. Specifically, the acoustic field in the thrombus was characterized (amplitude, homogeneity and variation between patients). The acoustic pressure and the temperature elevation in the intervening tissues were also evaluated. Finally, the pressure amplitude in local maxima due to reflection from the contralateral bone was estimated. The M1 segment is a common thrombus location and is associated with poor clinical outcome after intravenous rtPA treatment (Saarinen et al., 2012). Hence, the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery was considered as the targeted region of interest (ROI). The acoustic model used in this study was previously validated (Bouchoux et al., 2012). Good agreement was found between simulations based on CT scans and in vitro measurements in human skulls (R2=0.93 for transmitted wave amplitude). Thus, the simulation technique was employed for the prediction of acoustic fields.

Two transducers geometries described in literature were modeled. First, a 120-kHz unfocused transducer producing a broad, naturally-focused beam was considered (Bouchoux et al., 2012). Efficient thrombolysis enhancement has been shown in vitro and ex vivo using this frequency (Datta et al., 2006, 2008; Hitchcock et al., 2011). A weakly focused 500-kHz transducer producing a narrower beam was also modeled. Safe and efficient thrombolysis was also demonstrated in vitro and in vivo at 500 kHz (Saguchi et al., 2008; Wang Z. et al., 2008; Shimizu et al., 2012). Two transducer placement strategies were established. First, the transducer position was optimized for each patient, based on the location of the M1 segment and the geometry of the skull determined from the CT data. A landmark-based transducer placement strategy was also implemented. The landmark-based positioning of the transducer was based only on external, visible landmarks (canthomeatal lines) with no a-priori knowledge of the thrombus location. The CT-based positioning technique was compared to the landmark-based strategy for both transducers.

Methods

Computed tomography data

Twenty non-contrast head CT scans of patients with confirmed acute ischemic stroke were obtained. The CT scans were performed for diagnosis as part of the protocol for standard care of stroke patients at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. The CT data were anonymized and collected retrospectively. The study was approved by the Institutional Review board of the University of Cincinnati and the requirement of informed consent was waived.

The CT scans were acquired with a LightSpeed Pro 16 scanner (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK), following the standard imaging protocol for acute ischemic stroke services at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. The image resolution was 0.43 × 0.43 mm2 and the slice thickness was 5 mm. For each patient, the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery in the ischemic hemisphere was circumscribed by an experienced neuroradiologist (RS) using the Osirix software (Rosset et al., 2004). The M1 segment was outlined with a 5 mm-wide brush tool covering the entire artery on all axial images where the artery was visible (Fig. 1). Additionally, both lateral canthi and external acoustic meatuses were located and used for the transducer positioning procedure as external head landmarks. The M2 segments of the MCA were also outlined when identifiable in the axial CT images.

Fig. 1.

Axial CT image of an acute ischemic stroke patient. The green contour shows the M1 segment. For this patient, the thrombus appeared hyperdense on the image.

The CT scans with the corresponding landmarks and regions of interest were imported in Matlab (R2011b, Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) for further processing. For each patient, a three-dimensional (3D) image was assembled from the CT axial images. The gantry tilt was corrected, and a registration-based inter-slice interpolation technique (Penney et al., 2004) was applied in order to obtain a 3D image with an isotropic voxel size. A non-rigid registration algorithm (Rueckert et al., 1999) was used for the registration step of the interpolation method. A thickness of 5-mm in the axial direction was assumed for the M1 ROI.

Simulation of ultrasound propagation

Transcranial ultrasound propagation was simulated using a 3D finite-difference acoustic propagation model described in detail and validated previously (Bouchoux et al., 2012). Briefly, acoustomechanical parameter maps of heads were obtained from the CT images. For bone voxels, the acoustic parameters were estimated from their Hounsfield scale value using empirical relations established by Pichardo et al. (2011). Typical material properties were assigned to voxels corresponding to soft-tissues, air, and water (Table 1). Acoustic propagation in the attenuative heterogeneous media described by the parameter maps was modeled using stress-strain, momentum conservation and memory equations. Linear frequency-dependence of the attenuation was assumed for all materials. Shear wave propagation was not modeled as it was shown to be negligible in the case of low-frequency insonification of the temporal bone (Bouchoux et al., 2012). Acoustic pressures below 500 kPa peak to peak enhance rtPA thrombolysis (Datta et al., 2008; Saguchi et al., 2008). At such low amplitudes and frequencies, nonlinear propagation can also be neglected (Bouchoux et al., 2012). The simulation was computed in the time-domain using a staggered finite-difference scheme. The continuous-wave acoustic pressure field at the central frequency of the acoustic source was extracted for further analysis.

Table 1.

Acoustomechanical and thermal parameters used for simulations. For the sake of simplicity, the same properties were assigned to brain and periosteal tissue. Bone density was determined from CT data, the speed of sound c(ρ), and attenaution α(ρ) in bone were evaluated using the relations established by Pichardo et al. (2011). Soft tissue acoustic properties were from (Duck, 1990). Acoustic propagation in air was neglected and the speed of sound in air was set to 0. The other properties are listed and referenced in (Pulkkinen et al., 2011).

| Air | Water | Soft tissue | Bone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) | 1.2 | 1000 | 1000 | ρ |

| Speed of sound (m/s) | 0 | 1523 | 1545 | c(ρ) |

| Attenuation (Np/m/MHz) | 0 | 0 | 7 | α(ρ) |

| Specific heat (J/kg/°C) | 1006 | 4180 | 3640 | 1440 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/°C/m) | 0.002 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.43 |

| Perfusion rate (kg/m3/s) | 0 | 0 | 8.3 | 0 |

Thermal model

Temperature elevation in bone and soft tissue due to continuous-wave ultrasound exposure was also estimated computationally. The bioheat transfer equation (Pennes, 1948) was solved using the alternate-direction-implicit finite-difference method (Pisa et al., 2003). Power deposition due to the ultrasound exposure was evaluated using the simulated acoustic field (Pulkkinen et al., 2011). Maps of the thermal parameters (specific heat, heat conductivity and perfusion rate) were estimated from the CT data. The thermal properties listed in Table 1 were assigned to bone, soft tissue, air, and water voxels. The thermal simulation was computed in the time-domain and was conducted until the temperature reached steady state.

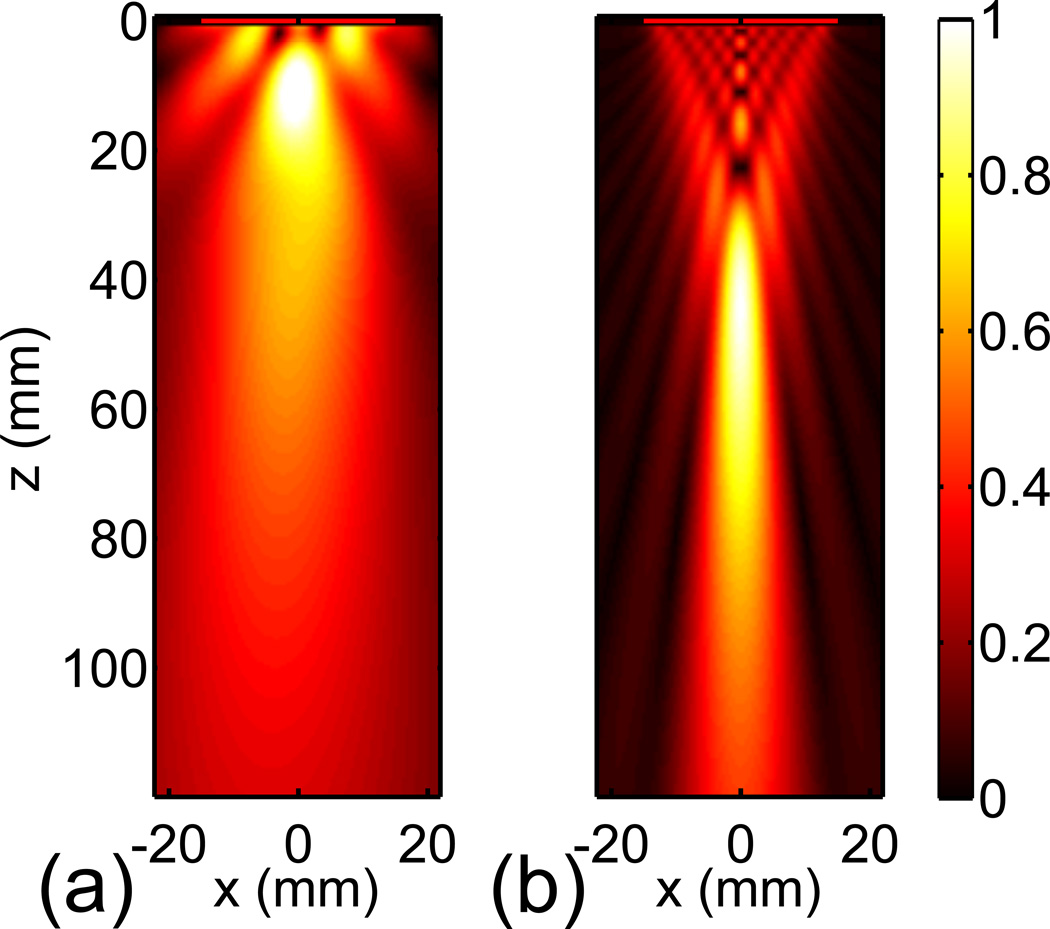

Transducer models

Ultrasound transducers were modeled as velocity sources in water, assuming an acoustically transparent transducer surface (Bouchoux et al., 2012). Air voxels between the acoustic source surface and the skin were replaced by water in order to mimic acoustic coupling gel. Two transducers were considered. First, a 30-mm diameter flat 120-kHz UET transducer prototype was modeled (Bouchoux et al., 2012). In order to obtain the source velocity distribution used in the propagation model, the nearfield acoustic holography technique (Maynard et al., 1985) was applied to an in vitro free-field measurement. The simulated free-field of this transducer is shown in Fig. 2a. The −6 dB beam width at 55 mm from the transducer surface, a typical distance to the center of the M1 segment of the MCA (Aaslid et al., 1982), was 27 mm. A 500-kHz transducer producing a narrower beam was also modeled as a uniformly vibrating piston. The 500-kHz transducer was geometrically focused at 80 mm and its diameter was 30 mm. The simulated free-field of the 500-kHz transducer is shown in Fig. 2b. The −6 dB beam width at 55 mm was 8 mm.

Fig. 2.

Normalized acoustic pressure simulated in the free field for the 120-kHz transducer (a) and the 500-kHz transducer (b).

CT-based transducer positioning

The position of the transducer maximizing the acoustic intensity in the M1 segment was determined based on the CT data. A simple acoustic transmission model with a fast computation time was used for this optimization process. The aim of this model was to give a first-approach estimate of the acoustic pressure in the M1 ROI as a function of the transducer position, taking into account the acoustic transmission through the skull, the transducer geometry, and its alignment with the M1 segment.

For each position of the transducer, i.e. each point on the head surface, the transducer was aligned with the centroid of the M1 region. When necessary, the transducer was moved backwards along its acoustic axis so that the compression of periosteal soft tissue caused by the transducer tilt was less than 50%. This simple rule was established empirically to obtain a realistic positioning strategy relative to the skin. The acoustic transmission through the bone was evaluated. The acoustomechanical parameters of the bone along the lines between the transducer surface and the centroid of M1 were extracted from the 3D parameter maps. A one-dimensional multi-layer model (Folds, 1977) was utilized to compute the acoustic intensity transmission coefficient from the acoustomechanical parameters profiles discretized into thin layers. The effective intensity transmission coefficient was estimated by averaging the local transmission coefficient in the zone covered by the transducer aperture. The free-field acoustic intensity spatially averaged in the M1 ROI was computed using the Rayleigh integral and was multiplied by the acoustic intensity transmission coefficient. The position of the transducer with the highest estimated acoustic intensity in the M1 ROI was selected for each patient, as illustrated in Fig. 3a and 3b.

Fig. 3.

Typical CT-based and landmark-based positioning. The estimated average acoustic intensity in the M1 segment is color-coded and displayed as the function of the transducer position, for the 120-kHz transducer (a), and the 500-kHz transducer (b). The ‘x’ indicates the CT-based position. The landmark-based positioning strategy is shown for the same patient (c). The four external head landmarks are represented by an ‘o’. The arrows show the (O, i⃗1, i⃗2, i⃗3) base. The green volume indicates the M1 region. The landmark-based position and the orientation of the 120-kHz and 500-kHz transducers are almost identical and represented in red and pink, respectively.

Landmark-based transducer positioning

A positioning scheme based on external head landmarks was also considered. The aim of this approach was to position the transducer relatively to simple external landmarks, only requiring the a-priori knowledge of which side of the brain is ischemic. First, an appropriate transducer placement relative to the two lateral canthi and external acoustic meatuses was determined. An orthonormal base (O, i⃗1, i⃗2, i⃗3) was constructed for each patient, so that i⃗1 was the vector going from the lateral canthus to the external acoustic meatus on the ischemic side, and i⃗2 was normal to the cantho-meatal plane, as shown in Fig. 3c. The maps of the transmitted acoustic intensity in M1 segment obtained for each subject (Fig. 3a and 3b) were projected to the (O, i⃗1, i⃗2) plane and averaged. The maximum of the averaged projections was selected as the position of the transducer center for the landmark-based positioning procedure. The vector from this point to the centroid of the union of the M1 regions of all subjects in the (O, i⃗1, i⃗2, i⃗3) base was selected as the transducer orientation.

The position and orientation of the transducer relative to the external landmarks (lateral canthus and external acoustic meatus) were determined for the 120-kHz transducer and the 500-kHz transducer using the CT scans. Thereafter, this scheme was used to position each transducer in order to calculate and evaluate the transcranial field in each patient. The distance between the transducer surface and the skin was adjusted as previously described.

Data processing

The acoustic and thermal simulations were implemented in Matlab, C, and CUDA™, a parallel computing platform. The computations were run on a PC with 10 GB memory, a 3.4 GHz processor with four cores (i7-2600, Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a graphical processing unit (GTX 550 Ti, NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The acoustic field was computed for each patient, transducer (120 kHz and 500 kHz), and positioning strategy (CT-based and landmark-based), giving a total of 80 simulations. The pressure amplitude fields were normalized by the maximum amplitude in the free field. For each case, the temperature increase due to ultrasound exposure was also simulated. For temperature simulations, the transducer excitation amplitude was set such that the maximum spatial acoustic intensity in the M1 segment averaged for all patients was 1 W/cm2. This arbitrary acoustic intensity was selected so that the temperature increase can be assessed for any ultrasound exposure parameters by multiplying the simulated temperature by the targeted temporal-average acoustic intensity in the M1 segment in W/cm2, based on a linear assumption.

In order to characterize the simulated acoustic fields and the temperature maps, six metrics were defined. First, the maximum relative pressure amplitude in the M1 ROI was evaluated by:

| (1) |

where P is the simulated pressure amplitude normalized by the maximum amplitude in the free field. The homogeneity of the acoustic field in the M1 region was characterized by the metric stdPM1, defined as follows:

| (2) |

where PM1 is the spatial average of P in the M1 ROI, and VM1 is the volume of the M1 ROI. The relative inter-patient variation of the acoustic pressure amplitude in the M1 segment was defined by:

| (3) |

where N is the number of patients. The peak acoustic pressure in the head was expected to be proximal to the transducer, as confirmed in the results section. Therefore, the relative pressure amplitude in intervening tissue was simply evaluated by the ratio between the peak acoustic pressure and the maximum in the M1 ROI:

| (4) |

The acoustic pressure in the non-targeted zone of the brain, indicating the presence of local maxima due to reflections from the contralateral bone, was characterized by the ratio:

| (5) |

The proximal volume is defined by the region in the cranial cavity within the −6 dB contour surface of the free field beam. The distal region represents the intracranial zone outside the focus, and is defined as the complement of the proximal region expanded with a 1 cm margin. Finally, the spatial maximum of the steady-state temperature increase was evaluated:

| (6) |

where ΔT is the steady state temperature increase computed for a transducer excitation set such that the spatial intensity in the M1 ROI was 1 W/cm2 on average.

The metrics defined by equations 1–6 were evaluated for all patients, transducers, and positioning strategies. The average and the standard deviation of the metrics were computed for the four setups. Student’s t-test was used to assess statistically significant difference between landmark-based and CT-based positioning strategies, and between the two transducers for the each positioning strategy. Similarly, Bartlett’s test was used to compare the variance of relPM1 between the setups. Differences were considered significant for p<0.05. Data are presented as a mean value and standard deviation.

Results

Transducer positioning

Twenty CT scans of subjects with acute ischemic stroke were collected. Patient ages ranged from 31 to 81 years (58.7±13.2) and 35% were female. The M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery was localized for all the subjects by an experienced neuroradiologist (RS). The average volume of the M1 ROI was 0.97±0.28 ml. The CT-based placement of both the 120-kHz and 500-kHz transducers was determined for each subject. In all the cases, the transducer was aligned such that the M1 segment was insonified through the temporal bone on the ischemic side (Fig. 3a and 3b). The landmark-based placement of the two transducers was also computed (Fig. 3c). Expressed in the (O, i⃗1, i⃗2, i⃗3) base, the 120-kHz transducer center was at (0.66; 0.10; 0) and its normal vector was (0.13; 0.38; 0.91). The 500-kHz transducer center was at (0.65; 0.10; 0) and its normal vector was (−0.11; 0.38; 0.92). In other words, for both transducers the landmark-based position was above the cantho-meatal line on the ischemic side, at about one third of the distance between the lateral canthus and the external acoustic meatus, and the orientation was slightly superior to the cantho-meatal plane. The distance from the transducer to the M1 ROI, the length of bone crossed by the acoustic axis and the average distance between the points in the M1 ROI and the transducer axis were measured (Table 2).

Table 2.

Geometric characterization of the CT-based and landmark-based positioning strategies for both transducers. Mean values ± standard deviation are presented.

| 120-kHz transducer | 500-kHz transducer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT-based | Landmark | CT-based | Landmark | |

| Distance between transducer center and centroid of M1 (mm) | 53.7±4.5* | 56.8±4.6* | 54.4±4.9+ | 56.8±4.6+ |

| Bone thickness along the central axis of the transducer (mm) | 2.5±0.7*^ | 3.0±1.0* | 2.8±0.6^ | 2.9±0.9 |

| Mean distance between M1 and transducer axis (mm) | 4.0 ±1.1*^ | 7.2 ±3.0* | 3.3 ±0.7+^ | 7.2±2.9+ |

indicate pairs with significant statistical difference (p<0.05)

Simulation results

Representative simulated acoustic fields and temperature maps for the two transducers and positioning strategies are shown in Fig. 4. In all cases, the maximum acoustic pressure in the head was observed either in the proximal temporal bone or between the transducer and the bone. In simulations with the 120-kHz transducer, a typical interference pattern with a half-wavelength distance (6.25 mm) between nodes was visible everywhere. A reflection from the contralateral bone was also identifiable in most of cases. For the 500-kHz transducer, standing waves were mostly visible between the transducer and the ipsilateral bone, and in the skull near the contralateral bone. For both transducers, the maximum temperature elevation was predicted in the proximal temporal bone. A temperature increase in the contralateral bone was also observed, but its amplitude was an order of magnitude lower. The maximum temperature in soft tissues was always in the periosteal tissue, between the bone and the transducer. The ratio between the maximum temperature elevation in the periosteal soft tissues and the maximum temperature in the bone was 70±12%. Similarly, the maximum temperature increase in brain was consistently proximal to the temporal bone. The ratio between the maximum temperature increase in brain and in bone was 42±9%. The steady state temperature was reached after about 3 minutes of continuous ultrasound exposure.

Fig. 4.

Simulated acoustic and temperature fields in a representative subject for the two transducers (120-kHz and 500-kHz), and the two placement techniques (CT-based and landmark-based). The bone is represented with a white contour and the air interface with a blue contour. The M1 segment is shown in green and the transducer in red. In the 3D rendering, the orange contour indicates the region where the acoustic pressure is larger than the half of the maximum pressure in the M1 ROI. The axial images show the maximum of the fields in a 5 mm-thick slice. Note that the transducer central axis is not in the axial plane.

The metrics defined by equations 1–6 were evaluated for all the simulations, and their distributions are shown in Fig. 5. The average and standard deviation of the metrics were computed for each setup and are reported in Table 3. In addition, the M2 segments of the MCA were identified for 9 subjects. The maximum pressure amplitude in the M2 ROI relative to the free field maximum was 41±12% for the 120-kHz transducer and 26±12% for the 500-kHz transducer. In order to estimate the transmission efficiency through the skull, the ratio between the average pressure in the M1 segment and the average pressure in the same location in the free field was computed. The transmission ratio was 72±13% at 120 kHz, and 47±15% at 500 kHz.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of the metrics maxPM1 (a), stdPM1 (b), relPM1 (c), Rproximal (c), Rdistal (d), and ΔTmax (e) for the two transducers (120-kHz and 500-kHz), and the two placement methods (CT-based and landmark-based). Each data point is represented by a ‘x’, the mean value by a ‘o’ and the standard deviation by a line.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the simulated fields using the metrics defined by equations 1–6, for the CT-based and landmark-based positioning strategies and both the 120-kHz and 500-kHz transducers. Mean values ± standard deviation are shown.

| 120-kHz transducer | 500-kHz transducer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | CT-based | Landmark | CT-based | Landmark |

| maxPM1 (%) | 53.9±10.5* | 48.6±10.6* | 50.1±11.2+ | 41.4±17.8+ |

| stdPM1 (%) | 21.5±4.3^ | 23.44±5.1 | 47.5±12.5+^ | 65.5±14.1+ |

| relPM1 (%) | ±18.0 | ±21.3 | ±26.4+ | ±47.9+ |

| Rproximal | 2.6±0.6^ | 2.8±0.7 | 2.0±0.7+^ | 2.9±1.9+ |

| Rdistal | 0.8±0.1*^ | 1.0±0.2* | 0.3±0.1^ | 0.3±0.1 |

| ΔTmax (°C) | 3.8±2.2*^ | 6.1±3.9* | 13.4±3.3+^ | 18.4±4.2+ |

indicate pairs with significant statistical difference (p<0.05)

Discussion

Transducer positioning

The temporal bone acoustic window was consistently selected by the CT-based positioning algorithm. The temporal bone window is classically used at higher frequencies for TCD (Aaslid et al., 1982; Alexandrov et al., 2007), and has also been chosen for UET (Alexandrov et al., 2004; Daffertshofer et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 2012). The distance between the transducer and the M1 segment found for both the landmark-based and the CT-based positioning techniques (in average 56±4.6 mm, Table 2) corresponded with distances usually observed for TCD (Aaslid et al., 1982). The temporal bone acoustic window was usually wider at 120 kHz than at 500 kHz as illustrated by Fig. 3. Therefore, the acoustic pressure transmitted to the M1 segment may be less sensitive to the transducer position at lower frequencies.

The CT-based positioning technique performed better than the landmark-based positioning strategy for both the 120-kHz and 500-kHz transducers. As expected, the optimization procedure resulted in a transducer placement with slightly shorter distance to the M1 ROI, shorter bone path along the acoustic axis and better alignment with the M1 segment, compared to the landmark-based alignment (Table 2). The resulting acoustic fields and thermal maps were different for these two transducers. For the 120-kHz transducer, CT-based and landmark-based positioning performed similarly, even if small significant differences were measured for maxPM1, Rdistal and ΔTmax (Table 3). However, with the 500-kHz transducer, large differences between the two placement methods were observed for all the metrics. Hence, the application of the landmark-based positioning technique appeared to be inadequate for the 500-kHz transducer. The beam generated by the 500-kHz transducer was relatively narrow (8 mm), which resulted in a low tolerance to the relatively inaccurate alignment with the M1 segment obtained with the landmark-based positioning. Other 500-kHz transducer geometries could be used to produce a broader acoustic beam suitable for the landmark-based alignment strategy.

In a clinical setting, the CT-based positioning could be determined using the standard head CT scan acquired for diagnostic. Whereas the CT-based positioning algorithm computation time is potentially negligible (<5 minutes in its current implementation), the accurate placement of the transducer may require a relatively complex stereotactic method. Alternatively, it has been proposed to position a 500-kHz therapeutic beam using a 2-MHz TCD signal obtained from the same probe (Azuma et al., 2010; Shimizu et al., 2012; Wang Z. et al., 2008). During the TCD examination preceding the treatment, the transducer is aligned with the MCA by maximizing the Doppler signal. The alignment of the therapeutic beam with the MCA benefits from the TCD alignment protocol. Transducer placement based on the TCD signal likely gives results similar to the CT image-based positioning technique described here. However, TCD examination requires experienced operators and may not be applicable to patients with temporal bone inadequate for TCD examination or for total occlusion of the blood flow in the MCA. The landmark-based placement technique is potentially superior in the time-critical context of UET. No supplementary examination is needed, and it can be applied to all patients using a simple headframe aligned with external head landmarks. However, this approach is only feasible for a broad low-frequency beam.

Acoustic pressure in the M1 segment

The estimated acoustic transmission coefficient through the temporal bone was 72±13% at 120 kHz, larger than 47±15% at 500 kHz. Transmission measured through human skulls in vitro at 120 kHz by Ammi et al. (2008) was in a similar range. As expected, the transmission through the bone decreased with increasing frequency. However, the slight focusing of the 500-kHz transducer (Fig. 1) compensated for its lower transmission efficiency. Hence, the simulated maximum acoustic pressure in M1 relative to the free field maximum was similar for both transducers (maxPM1, Table 3). The standard deviation of the pressure in the M1 segment (stdPM1) was significantly larger for the 500-kHz transducer (47.5±12.5%) than for the 120-kHz transducer (21.5±4.3%), indicating that the acoustic field was more heterogeneous in the M1 region. Indeed, the broader 120-kHz beam allowed a relatively homogeneous irradiation of the M1 segment, whereas the 500-kHz beam only partially covered it. The pressure amplitude in the M2 segment of the MCA (another possible location of intracranial thrombi) relative to the free field maximum was higher with the broad beam produced by the 120-kHz transducer (41±12%) than with the focused 500-kHz beam (26±12%).

The standard deviation of the variation of the acoustic pressure in M1 among patients was slightly lower for the 120-kHz transducer than for the 500-kHz transducer (relPM1, Table 3). As the bone is more acoustically transparent at 120 kHz, a lower inter-patient variation could be expected. However interference caused by reflections within the skull was more prevalent at 120 kHz (Fig. 4), and may have introduced an additional cause of inter-patient variation. In the TUCSON study utilizing 2-MHz TCD, Barlinn et al. (2013) simulated the in situ acoustic peak rarefaction pressures in 20 subjects. Acoustic pressures between 8 and 68 kPa with a 51.3% relative standard deviation were reported. In our study, significantly smaller relative standard deviations in pressure amplitude were predicted for both the 120-kHz and the 500-kHz transducer (18.0% and 26.4%, respectively). The ratio between the maximum and minimum amplitudes in the pressure range reported by Barlinn et al. (2013) at 2 MHz was 8.5, whereas it was 2.1 and 3 for the 120-kHz and 500-kHz transducers modeled in our study, respectively. The simple acoustic model used by Barlinn et al. (2013) does not take into account the heterogeneity of the bone, variation in bone properties between patients, phase aberration and acoustic reflection. Thus, the inter-patient variation of in situ acoustic amplitude that they report may be underestimated. Therefore, it appears that frequencies in the sub-megahertz range may allow a more consistent insonification of the thrombus than TCD.

The inter-patient variation for low-frequency UET could be reduced by applying a correction to the transducer voltage for each patient. This correction can be determined from simulations based on the CT data (Bouchoux et al., 2012). Another possible approach is to adjust the transducer voltage based on the online monitoring of the treatment (O’Reilly and Hynynen, 2012).

Potential causes of side-effects

Local acoustic pressure maxima with amplitude larger than the amplitude in the M1 segment are potential sites for negative bioeffects. In particular, uncontrolled strong acoustic cavitation has been associated with negative side-effects in the brain (Baron et al., 2009; McDannold et al., 2012), and has the highest likelihood to occur at these local pressure maxima.

The spatial peak acoustic pressure was located either in the temporal bone or in the periosteal tissue insonified by the transducer, as illustrated by Fig. 4. The simulated peak pressure was 2.6±0.6 and 2.0±0.7 times higher than the pressure in the M1 segment (Rproximal, Table 3) for the 120-kHz and the 500-kHz transducer, respectively. Therefore, the likelihood of negative side-effects due to the ultrasound exposure is the highest in the periosteal tissue, with limited clinical significance. For the same acoustic pressure in M1, the pressure in periosteal tissue was the lowest with the 500-kHz transducer because of its focusing. The 120-kHz transducer had a natural focus at about 1 cm (Fig. 1), which lies in the periosteal tissue and the temporal bone. A different geometry of the 120-kHz transducer may reduce the pressure amplitude in the periosteal tissue relative to the acoustic pressure in M1.

Local acoustic pressure maxima in the contralateral hemisphere with amplitude up to 1.1 times the amplitude in the targeted zone were predicted for the 120-kHz transducer (Rdistal, Fig. 5). These local maxima were due to the interference between the transmitted wave and the wave reflected from the contralateral bone. In some cases, the reflected wave was visibly refocused by the concave shape of the contralateral bone. In order to avoid significant negative side-effects, the amplitude of these local maxima should be lower than the amplitude in the M1 segment. The amplitude of constructive interference may be reduced by applying random modulation techniques to the excitation signal (Furuhata and Saito, 2013; Tang and Clement, 2010, 2009), or by increasing the insonification frequency. Indeed, the acoustic pressure near the contralateral bone and the amplitude of interference was significantly lower for the 500-kHz transducer, in agreement with the results of Deffieux and Konofagou (2010), who predicted limited standing-wave interference in the human skull exposed to 500 kHz ultrasound.

The maximum simulated temperature increase for 1 W/cm2 in the M1 segment was higher for the 500-kHz transducer (13.4±3.3°C) than for the 120-kHz transducer (3.8±2.2°C, Table 3). The higher acoustic attenuation in bone at 500 kHz explains this difference, as heat deposition is proportional to attenuation. Hence, the maximum acoustic power that can be transmitted to the thrombus without causing thermal damage may be higher with the 120-kHz transducer than with the 500-kHz transducer. Larger temperature increases were obtained for the landmark-based positioning strategy, particularly for the 500-kHz transducer. Indeed, a higher transducer voltage was required to obtain 1 W/cm2 in the M1 segment with the landmark placement compared to the CT-based positioning. The maximum temperature elevation in soft tissue was located in the periosteal tissue, between the transducer and the bone. The largest temperature increase in brain tissue was located next to the insonified bone and was slightly lower than the temperature increase in periosteal tissue. Correspondingly, a slight difference of temperature between the two opposite interfaces of the insonified bone was measured in vitro by Nahirnyak et al. (2007).

In order to assess the order of magnitude of temperature increase in the temporal bone for acoustic regimes that have been shown to enhance thrombolysis, the exposure parameters of published studies can be used. At 120-kHz, with an 80 % duty cycle and in presence of a contrast agent, the maximum in vitro clot mass loss was measured at 0.32 MPa peak to peak by Datta et al. (2008). A targeted temporal-average acoustic intensity in the thrombus of 0.7 W/cm2 can be calculated from these parameters. For the CT-based placement strategy, the corresponding average temperature increase in the bone is 0.7 × ΔTmax = 2.4°𝖢. Thermal damage in the brain is unlikely with this temperature increase (McDannold et al., 2004).

Saguchi et al. (2008) reported effective UET in a rat model where the thrombus was exposed to 0.8 W/cm2 490-kHz ultrasound. Using ΔTmax for the CT-based position of the 500-kHz transducer (Table 3), an average steady state temperature increase in the bone of 9.9°C for a 0.8 W/cm2 average in situ intensity can be calculated. As noted in our study, the temperature increase in surrounding soft tissues is about half the maximum temperature increase in bone. In order to avoid tissue heating, Saguchi et al. (2008) performed intermittent irradiation with two minutes exposures followed by pauses. As the steady state is not reached during two-minute exposures, new simulations with the intermittent ultrasound should be conducted for an accurate estimation. To assess the likelihood of thermal damage, the thermal dose could be computed from the simulated temperature elevation. Nevertheless, it is likely that these exposure parameters do not cause thermal damage as Shimizu et al. (2012) did not report any adverse effects in primate brain with these exposure parameters.

Limitations of the study

This study relies on simulations based on CT scans. The acoustic propagation model has been previously validated for trans-temporal insonification at 120 kHz (Bouchoux et al., 2012). A good correlation between simulated amplitudes and corresponding in vitro measurements was obtained (R2=0.93), but the model tended to underestimate acoustic transmission slightly. This underestimation may cause an overestimation of the pressure in periosteal tissue, bone temperature, and inter-patient variation. Similarly, the amplitude of the wave reflected from the contralateral bone was slightly overestimated by the model when compared with measurements. The acoustic propagation model has not been validated at 500 kHz. Deffieux and Konofagou (2010) found good agreement between simulations and in vitro measurements at 550 kHz in one human skull using a similar model. However, additional experiments in several specimens would be required to validate the model and assess its accuracy.

Nahirnyak et al. (2007) measured in vitro a temperature increase of 0.6°C on the surface of temporal bone exposed to 120-kHz ultrasound with a 0.25 MPa peak-to-peak pressure in the free field and an 80% duty cycle. To compare their in vitro measurement with the values of ΔTmax obtained by simulation in patient heads (Table 3), the equivalent temporal-average acoustic intensity in the M1 segment must be assessed. A simple calculation using maxPM1 = 53.9% (Table 3), shows that 0.12 W/cm2 intensity in the M1 segment would be obtained with the parameters used by Nahirnyak et al. A temperature increase in the bone of 0.12 × ΔTmax = 0.46°𝖢 is obtained. The simulated temperature increase (0.46°C) is in the range of the in vitro measurement by Nahirnyak et al. (0.6°C), which partially validates the temperature simulations performed at 120 kHz in our study. Nahirnyak et al. measured a temperature increase twice larger at 1 MHz than at 120 kHz. Our study predicted a temperature elevation 3.5 times larger at 500 kHz than at 120 kHz. Therefore, the temperatures simulated at 500 kHz in our study may be overestimated. Also, the temperature in periosteal soft-tissue may have been underestimated because transducer self-heating was neglected.

The clinical applicability of the low-frequency UET setups evaluated in this study relies on the existence of exposure parameters allowing effective thrombolysis enhancement without causing significant negative bioeffects. The acoustic pressure in the M1 segment has to be sufficient for effective thrombolysis enhancement in all patients, while the pressure elsewhere (particularly in intervening tissues and contralateral locations) should not cause mechanical or thermal damage. Thermal damage can be assessed in brain using a thermal dose calculation (McDannold et al., 2004) and avoided in bone and periosteal tissue by following the Food and Drug Administration recommendations on the thermal index for cranial bone (Nelson et al., 2009). The acoustic pressure threshold for negative bioeffects caused by cavitation cannot be simply assessed using the mechanical index, which does not apply for low-frequency waves with a high duty cycle (Apfel and Holland, 1991). The acoustic pressure range for safe insonification of brain tissue for frequencies in the sub-megahertz range can be determined in animal models and is under investigation (Nedelmann et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2006; Shimizu et al., 2012). Similarly, the pressure range for efficient thrombolysis enhancement depends on the conditions of the treatment (frequency, presence of a contrast agent) and can be assessed in vitro (Datta et al., 2008, 2006; Hitchcock et al., 2011; Wang Z. et al., 2008) or in animal models (Ren et al., 2011; Saguchi et al., 2008; Wang B. et al., 2008). Considering experimentally established pressure ranges for safe and efficient ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis, the clinical applicability of a treatment can be assessed using the results of the present study.

The performance of the transducers and the evaluation of predicted acoustic fields are limited to the specific geometries considered. The metrics reported in Table 3 provide insight into the performance of low-frequency UET for the two transducer alignment strategies, but do not allow a complete evaluation of other frequencies and geometries. Note that the aim of our study was not to determine an optimal transducer geometry or frequency. However, the design and evaluation of a particular UET system could be performed using the methods described in this study. Finally, additional subjects may be required to represent the variations in head geometry and bone properties thoroughly.

Conclusion

Acoustic pressure and temperature fields obtained with low-frequency UET were evaluated in 20 acute ischemic stroke patients by simulations based on CT data. The position of the transducer maximizing the acoustic pressure in the M1 segment of the MCA was found to be through the temporal bone in all patients. A 120-kHz transducer with a broad collimated beam allowed homogeneous insonification of the M1 segment. With this transducer, a positioning based on external landmarks performed almost as well as an optimized placement based on CT-data. A slightly focused 500-kHz transducer was also modeled. Its narrower beam did not allow homogeneous insonification of the M1 segment, and results obtained with the landmark-based positioning were significantly degraded compared to the CT-based placement. On the other hand, the acoustic pressure in intervening tissues and the amplitude of constructive interference in the contralateral hemisphere were lower with the 500-kHz transducer than with the 120-kHz. However, the predicted temperature elevation in the temporal bone was significantly higher with the 500-kHz, which could limit the acoustic energy that can be transmitted to the brain without causing thermal damage. The variation of the acoustic pressure in the M1 segment between patients was similar for the two transducers. The relative standard deviation of the acoustic pressure in the M1 segment was below 26.4%. These results demonstrated that a consistent insonification of the thrombus can be achieved in the sub-megahertz frequency range. A transducer positioning technique based on the analysis of the head CT and an alignment strategy using external landmarks were also developed.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (number R01 NS047603).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H. Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:769–774. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov AV, Molina CA, Grotta JC, Garami Z, Ford SR, Alvarez-Sabin J, Montaner J, Saqqur M, Demchuk AM, Moyé LA, Hill MD, Wojner AW. Ultrasound-Enhanced Systemic Thrombolysis for Acute Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2170–2178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov AV, Sloan MA, Wong LKS, Douville C, Razumovsky AY, Koroshetz WJ, Kaps M, Tegeler CH Committee for the AS of NPG. Practice Standards for Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound: Part I—Test Performance. J Neuroimaging. 2007;17:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2006.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammi AY, Mast TD, Huang I-H, Abruzzo TA, Coussios C-C, Shaw GJ, Holland CK. Characterization of Ultrasound Propagation Through Ex-vivo Human Temporal Bone. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1578–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfel RE, Holland CK. Gauging the likelihood of cavitation from short-pulse, low-duty cycle diagnostic ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1991;17:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(91)90125-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma T, Ogihara M, Kubota J, Sasaki A, Umemura S, Furuhata H. Dual-frequency ultrasound imaging and therapeutic bilaminar array using frequency selective isolation layer. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2010;57:1211–1224. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2010.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlinn K, Tsivgoulis G, Molina CA, Alexandrov DA, Schafer ME, Alleman J, Alexandrov AV Investigators for the T. Exploratory analysis of estimated acoustic peak rarefaction pressure, recanalization, and outcome in the transcranial ultrasound in clinical sonothrombolysis trial. J Clin Ultrasound. 2013;41:354–360. doi: 10.1002/jcu.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron C, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Meairs S, Fink M. Simulation of Intracranial Acoustic Fields in Clinical Trials of Sonothrombolysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens S, Spengos K, Daffertshofer M, Schroeck H, Dempfle CE, Hennerici M. Transcranial ultrasound-improved thrombolysis: diagnostic vs. therapeutic ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27:1683–1689. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchoux G, Bader KB, Korfhagen JJ, Raymond JL, Shivashankar R, Abruzzo TA, Holland CK. Experimental validation of a finite-difference model for the prediction of transcranial ultrasound fields based on CT images. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:8005–8022. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/23/8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffertshofer M, Gass A, Ringleb P, Sitzer M, Sliwka U, Els T, Sedlaczek O, Koroshetz WJ, Hennerici MG. Transcranial Low-Frequency Ultrasound-Mediated Thrombolysis in Brain Ischemia. Stroke. 2005;36:1441–1446. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170707.86793.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, Ammi AY, Mast TD, de Courten-Myers GM, Holland CK. Ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis using Definity® as a cavitation nucleation agent. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1421–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, McAdory LE, Tan J, Porter T, De Courten-Myers G, Holland CK. Correlation of cavitation with ultrasound enhancement of thrombolysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1257–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffieux T, Konofagou EE. Numerical study of a simple transcranial focused ultrasound system applied to blood-brain barrier opening. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2010;57:2637–2653. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2010.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duck FA. Physical properties of tissue: a comprehensive reference book. Academic Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Folds DL. Transmission and reflection of ultrasonic waves in layered media. J Acoust Soc Am. 1977;62:1102–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Fry FJ, Barger JE. Acoustical properties of the human skull. J Acoust Soc Am. 1978;63:1576. doi: 10.1121/1.381852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhata H, Saito O. Comparative Study of Standing Wave Reduction Methods Using Random Modulation for Transcranial Ultrasonication. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39:1440–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock KE, Ivancevich NM, Haworth KJ, Caudell Stamper DN, Vela DC, Sutton JT, Pyne-Geithman GJ, Holland CK. Ultrasound-Enhanced rt-PA Thrombolysis in an ex vivo Porcine Carotid Artery Model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:1240–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland CK, Shaw GJ, Datta S. Therapeutic Ultrasound: Mechanisms to Applications. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2011. Ultrasound-Enhanced Thrombolysis. [Google Scholar]

- Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Bruno A, Connors JJ, Demaerschalk BM, Khatri P, McMullan PW, Qureshi AI, Rosenfield K, Scott PA, Summers DR, Wang DZ, Wintermark M, Yonas H. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri P, Abruzzo T, Yeatts SD, Nichols C, Broderick JP, Tomsick TA. Good clinical outcome after ischemic stroke with successful revascularization is time-dependent. Neurology. 2009;73:1066–1072. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b9c847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquet F, Pernot M, Aubry J-F, Montaldo G, Marsac L, Tanter M, Fink M. Non-invasive transcranial ultrasound therapy based on a 3D CT scan: protocol validation and in vitro results. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2597–2613. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/9/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsac L, Chauvet D, Larrat B, Pernot M, Robert B, Fink M, Boch AL, Aubry JF, Tanter M. MR-guided adaptive focusing of therapeutic ultrasound beams in the human head. Med Phys. 2012;39:1141–1149. doi: 10.1118/1.3678988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard JD, Williams EG, Lee Y. Nearfield acoustic holography: I. Theory of generalized holography and the development of NAH. J Acoust Soc Am. 1985;78:1395–1413. [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Arvanitis CD, Vykhodtseva N, Livingstone MS. Temporary Disruption of the Blood–Brain Barrier by Use of Ultrasound and Microbubbles: Safety and Efficacy Evaluation in Rhesus Macaques. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3652–3663. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. MRI investigation of the threshold for thermally induced blood–brain barrier disruption and brain tissue damage in the rabbit brain. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:913–923. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meairs S, Alonso A, Hennerici MG. Progress in Sonothrombolysis for the Treatment of Stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:1706–1710. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.636332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina CA, Ribo M, Rubiera M, Montaner J, Santamarina E, Delgado-Mederos R, Arenillas JF, Huertas R, Purroy F, Delgado P, Alvarez-Sabín J. Microbubble Administration Accelerates Clot Lysis During Continuous 2-MHz Ultrasound Monitoring in Stroke Patients Treated With Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator. Stroke. 2006;37:425–429. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000199064.94588.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith S, Sheehan J, Medel R, Wintermark M, Eames M, Snell J, Kassell NF, Elias WJ. Potential intracranial applications of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:215–221. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.JNS12449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahirnyak V, Mast TD, Holland CK. Ultrasound-induced thermal elevation in clotted blood and cranial bone. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:1285–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelmann M, Reuter P, Walberer M, Sommer C, Alessandri B, Schiel D, Ritschel N, Kempski O, Kaps M, Mueller C, Bachmann G, Gerriets T. Detrimental Effects of 60 kHz Sonothrombolysis in Rats with Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:2019–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TR, Fowlkes JB, Abramowicz JS, Church CC. Ultrasound biosafety considerations for the practicing sonographer and sonologist. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:139–150. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly MA, Hynynen K. Blood-Brain Barrier: Real-time Feedback-controlled Focused Ultrasound Disruption by Using an Acoustic Emissions–based Controller. Radiology. 2012;263:96–106. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11111417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennes HH. Analysis of tissue and arterial blood temperatures in the resting human forearm. J Appl Physiol. 1948;85:5–34. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penney GP, Schnabel JA, Rueckert D, Viergever MA, Niessen WJ. Registration-based interpolation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:922–926. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.828352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo S, Sin VW, Hynynen K. Multi-frequency characterization of the speed of sound and attenuation coefficient for longitudinal transmission of freshly excised human skulls. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:219–250. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/1/014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisa S, Cavagnaro M, Piuzzi E, Bernardi P, Lin JC. Power density and temperature distributions produced by interstitial arrays of sleeved-slot antennas for hyperthermic cancer therapy. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech. 2003;51:2418–2426. [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen A, Huang Y, Song J, Hynynen K. Simulations and measurements of transcranial low-frequency ultrasound therapy: skull-base heating and effective area of treatment. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:4661–4683. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/15/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S-T, Long L-H, Wang M, Li Y-P, Qin H, Zhang H, Jing B-B, Li Y-X, Zang W-J, Wang B, Shen X-L. Thrombolytic effects of a combined therapy with targeted microbubbles and ultrasound in a 6 h cerebral thrombosis rabbit model. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;33:74–81. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0644-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel CH, Zimmermann P, Jensen-Kondering U, Stingele R, Deuschl G, Jansen O. The Importance of Size Successful Recanalization by Intravenous Thrombolysis in Acute Anterior Stroke Depends on Thrombus Length. Stroke. 2011;42:1775–1777. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.609693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosset A, Spadola L, Ratib O. OsiriX: an open-source software for navigating in multidimensional DICOM images. J Digit Imaging. 2004;17:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10278-004-1014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, Hill DL, Leach MO, Hawkes DJ. Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: application to breast MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18:712–721. doi: 10.1109/42.796284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen JT, Sillanpää N, Rusanen H, Hakomäki J, Huhtala H, Lähteelä A, Dastidar P, Soimakallio S, Elovaara I. The mid-M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery is a cutoff clot location for good outcome in intravenous thrombolysis. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:1121–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saguchi T, Onoue H, Urashima M, Ishibashi T, Abe T, Furuhata H. Effective and Safe Conditions of Low-Frequency Transcranial Ultrasonic Thrombolysis for Acute Ischemic Stroke Neurologic and Histologic Evaluation in a Rat Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke Model. Stroke. 2008;39:1007–1011. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F, Gerriets T, Walberer M, Mueller C, Rolke R, Eicke BM, Bohl J, Kempski O, Kaps M, Bachmann G, Dieterich M, Nedelmann M. Brain edema and intracerebral necrosis caused by transcranial low-frequency 20-kHz ultrasound: a safety study in rats. Stroke J Cereb Circ. 2006;37:1301–1306. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217329.16739.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu J, Fukuda T, Abe T, Ogihara M, Kubota J, Sasaki A, Azuma T, Sasaki K, Shimizu K, Oishi T, Umemura S, Furuhata H. Ultrasound Safety with Midfrequency Transcranial Sonothrombolysis: Preliminary Study on Normal Macaca Monkey Brain. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2012;38:1040–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SC, Clement GT. Acoustic standing wave suppression using randomized phase-shift-keying excitations. J Acoust Soc Am. 2009;126:1667–1670. doi: 10.1121/1.3203935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SC, Clement GT. Standing-wave suppression for transcranial ultrasound by random modulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010;57:203–205. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2028653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang L, Zhou X-B, Liu Y-M, Wang M, Qin H, Wang C-B, Liu J, Yu X-J, Zang W-J. Thrombolysis effect of a novel targeted microbubble with low-frequency ultrasound in vivo. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:356–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Moehring MA, Voie AH, Furuhata H. In Vitro Evaluation of Dual Mode Ultrasonic Thrombolysis Method for Transcranial Application with an Occlusive Thrombosis Model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoud AD, Franckena M, van der Lugt A, Koudstaal PJ, Dippel EDWJ. Inadequate acoustical temporal bone window in patients with a transient ischemic attack or minor stroke: role of skull thickness and bone density. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]