Abstract

Mutations in ACTA2 predispose to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections as well as coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease. Here we examined the risk of aortic dissections, stroke and myocardial infarct with pregnancy in women with ACTA2 mutations. Of the 53 women who had a total of 137 pregnancies, eight had aortic dissections in the third trimester or the postpartum period (6% of pregnancies). One woman also had a myocardial infarct that occurred during pregnancy that was independent of her aortic dissection. Compared to the population-based frequency of peripartum aortic dissections of 0.6%, the rate of peripartum aortic dissections in women with ACTA2 mutations is much higher (8 out of 39; 20%). Six of these dissections initiated in the ascending aorta (Stanford type A), three of which were fatal. Three women had ascending aortic dissections at diameters less that 5.0 cm (range 3.8 to 4.7 cm). Aortic pathology showed mild to moderate medial degeneration of the aorta in three women. Of note, five of the women had hypertension either during or before the pregnancy. In summary, the majority of women with ACTA2 mutations did not have aortic or other vascular complications with pregnancy. However, these findings show that pregnancy is associated with significant risk for aortic dissections in women in whom diagnosis of ACTA2 mutation has not been made. Women with ACTA2 mutations who are planning to get pregnant should be counseled about this risk of aortic dissections, and proper clinical management should be initiated to reduce this risk.

Keywords: ACTA2, aortic dissection, stroke, myocardial infarct, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Hemodynamic changes, such as increased intravascular volume, heart rate, and cardiac output occur during pregnancy. These changes are believed to be responsible for the increased risk for acute aortic dissections during pregnancy, and this risk is particularly high in women who have single gene mutations predisposing them to thoracic aortic aneurysms leading to aortic dissections (TAAD) [Mashini et al., 1987; Milewicz et al., 2008a; Poppas et al., 1997]. For example, individuals with Marfan syndrome have progressive and asymptomatic enlargement of the aorta at the level of the sinuses of Valsalva (termed aortic root aneurysms) that can lead to life-threatening acute aortic dissections. Aortic disease in patients with Marfan syndrome is managed by initiating beta adrenergic blockers, monitoring the size of the aneurysm with serial imaging, and surgically repairing the aneurysm when the aortic root diameter reaches 5.0 to 5.5. cm [Hiratzka et al., 2010]. Using this protocol, acute aortic dissections in patients with MFS can be prevented and the life expectancy extended [Silverman et al., 1995]. Retrospective studies of women with Marfan syndrome have shown 4–7 % of pregnancies were complicated by aortic dissection or rapid aortic root dilatation[Lind and Wallenburg, 2001; Lipscomb et al., 1997; Pacini et al., 2009], while prospective studies indicate this risk is low in women with aortic root enlargement less than 4.0 cm or 4.5 cm [Meijboom et al., 2005; Rossiter et al., 1995].

Other single gene mutations predispose to thoracic aortic aneurysms leading to aortic dissections in families in the absence of syndromic features, termed familial TAAD [Milewicz et al., 2008b]. The most commonly altered gene causing familial TAAD is ACTA2 which is responsible for 10 - 14% of familial disease [Disabella et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2007; Hoffjan et al., 2011; Morisaki et al., 2009; Renard et al., 2013]. In addition to TAAD, individuals with certain ACTA2 mutations are also at risk for early onset coronary artery disease, stroke, and cerebrovascular disease [Guo et al., 2009; Milewicz et al., 2010]. The risk of aortic dissection and other vascular complications in pregnant women with ACTA2 mutations is not known, although there have been a few reports of ascending and descending dissections during pregnancy in women with ACTA2 mutations [Morisaki et al., 2009; Yoo et al., 2010]. To understand the risk of vascular disease associated with pregnancy in women with ACTA2 mutations, we performed a retrospective review of medical records of women with ACTA2 mutations to examine the frequency of aortic dissections, myocardial infarction, and stroke during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Board, and proper informed consent was obtained from study participants. Individuals who were diagnosed with an ACTA2 mutation by our research laboratory or a DNA diagnostic laboratory and their relatives who are obligate carriers or had a 50% risk of inheriting the ACTA2 mutation and affected with aortic disease, were included in this study. Demographic data, finding of aortic and vascular disease including stroke and myocardial infarct, age at diagnosis, echocardiographic and radiologic findings, surgical and medical management, outcome, and medical history were extracted from the medical records (E.S.R and D.M.M.). Thoracic aortic dissections were classified based on the Stanford classification as Type A (aortic dissections initiating in the ascending aorta that may extend to the descending aorta) or B (aortic dissections that do not involve the ascending aorta and initiating in the descending thoracic aorta just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery). When available, computed tomography (CT) and echocardiographic images were independently read by a cardiothoracic surgeon with expertise in aortic disease (A.L.E.). Aortic measurements at different anatomical positions were obtained. Surgical pathology materials were obtained and stained with H&E and Movat’s pentachrome stains and examined by L.M.B., D.G., and D.M.M. Data was analyzed and categorical variables were presented in frequencies and percentages.

RESULTS

Fifty-three women with ACTA2 mutations had a total of 137 delivered pregnancies. Eight of these women had an acute aortic dissection during pregnancy or in the postpartum period. Thus, 6% of the pregnancies were complicated by acute aortic dissections. Four of the women experienced the aortic dissection during the third trimester at 28–37 weeks gestation and underwent emergency cesarean section, followed by surgical repair of the aorta. The other four women had dissections in the postpartum period at 6–14 days after delivery. There were no fetal deaths in these cases. Three of the women had never been pregnant, one had been pregnant once, three had been pregnant twice, and one had been pregnant three times without vascular complications.

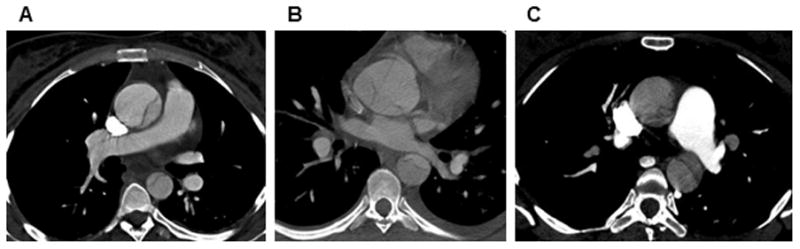

In our cohort of individuals with ACTA2 mutations, 39 women had thoracic aortic dissections and thus 20% of dissections (8 out of 39) were associated with pregnancy. The eight women were 29 to 43 years old (mean 34.5 years) at the time of dissection. Six of the women had type A aortic dissections and one had a type B aortic dissection. Patient 5 had an unspecified dissection that required graft replacement of the abdominal aorta and was assumed to be a type B dissection. CT imaging studies at the time of presentation were available for three women who had type A dissections (Patients 2, 7and 8). These images showed the maximal aortic diameters to be 4.2 cm (ascending aorta), 4.7 cm (aortic root), and 3.8 cm (ascending aorta), respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced axial CT images of the chest showing dissection in the ascending aorta measuring 4.2 cm in Patient 2 (A); dissecting aneurysm arising from the aortic root measuring 4.7 cm in Patient 7 (B); and ascending aortic dissection measuring 3.8 cm in Patient 8.

All women presented directly or were transferred to a tertiary care facility immediately after onset of symptoms. Limited medical records were available for Patients 4 and 5. But of the six women with complete records, all women presented with severe and sudden onset of pain in the chest, back, neck and/or abdomen. Pulse deficits, syncope, hypotension, hypertension and neurological deficits were also noted in some of the women at presentation (Table 1). All six women with type A dissections underwent emergency surgery and replacement of the ascending aorta, but three women died of post-operative complications. The death certificate of Patient 4 indicated the cause of death as dissecting aneurysm of the aortic arch and post-operative cerebral thrombosis. Patient 6 presented to the emergency department at 31 weeks gestation with sudden onset of chest pain and hypotension and was found to have proximal dissection and severe aortic insufficiency by cardiac catheterization. She underwent emergency cesarean section, followed by surgical repair of the ascending aorta but died post-operatively. Patient 3 presented to the emergency department at 28 weeks gestation after she complained of back pain and collapsed at home. She had no femoral pulses on exam and underwent femoral embolectomies and femoral to femoral bypass, followed by an emergency cesarean section. An intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a thoracic aortic dissection, which prompted transfer to another facility where she underwent repair of the ascending aorta but died of complications post-operatively.

Table I.

Disease presentation, management, and outcome of women with ACTA2 mutations and peripartum aortic dissections.

| Patient | ACTA2 mutation | Age | Gestational status | Obstetric historya | Type of dissection | Symptoms | Diagnostic imaging | Aortic diameterb | Obstetric procedure | Cardiovascular procedure | In-hospital complications | Other medical history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | p.Arg39His | 35 | 9 days postpartum | G1P1 | Type B | Chest, back pain; HTN | CT | NA | Emergency cesarean | None | Pre-eclampsia | None |

| 2 | p.Arg39Cys | 30 | 28 weeks gestation | G4P2 | Type A | Headache; visual changes; facial, pedal edema; HTN; epigastric pain | CT | 4.2 cm (ascending, CT) | Emergency cesarean; hysterectomy | Replacement of ascending aorta | HTN | Toxemia |

| 3 | p.Met49Val | 35 | 28 weeks gestation | G3P2 | Type A | Back pain; syncope; absent femoral pulses | TEE | NA | Emergency cesarean | Femoral thrombectomy; femoral-femoral bypass; replacement of ascending aorta | Multiple organ failure; postpartum pre-eclampsia; coagulation abnormalities; death | None |

| 4 | p.Arg149Cys | 29 | 1 week postpartum | G4P4 | Type A | NA | NA | NA | Vaginal delivery | Failed repair | Cerebral thrombosis; death | HTN |

| 5 | p.Arg149Cys | 30 | 2 weeks postpartum | G3P3 | Type B | NA | NA | NA | Vaginal delivery | Replacement of abdominal aorta | NA | MI |

| 6 | p.Arg149Cys | 37 | 31 weeks gestation | G1P0 | Type A | Chest pain; hypotension; diaphoresis; shortness of breath; nausea | Cardiac catheterization | NA | Emergency cesarean | Failed repair | Death | None |

| 7 | p.Gly275Ala | 43 | 37 weeks gestation | G2P0 | Type A | Neck pain; throat tightness; epigastric pain; vomiting | TTE, CT | 4.7 cm (aortic root, CT) | Emergency cesarean | Replacement of ascending aorta, resuspension of the aortic valve | None | MI; HTN; gestational diabetes |

| 8 | p.Ser302Ala | 37 | 6 days postpartum | G3P2 | Type A | Chest, jaw pain; blurred vision; syncope | CT | 3.8 cm (ascending, CT) | Elective cesarean | Replacement of ascending aorta and transverse aortic arch | Neurological deficits; stroke | None |

G-gravida; # of pregnancies, P-para; # of delivered pregnancies at disease presentation;

aortic diameters are provided in cm and the anatomic location with widest diameter and imaging modality used for measurement are in parenthesis; HTN, hypertension; MI- myocardial infarction; TEE- transesophageal echocardiogram; TTE- transthoracic echocardiogram; CT- computed tomography; NA- data not available.

Two of the eight women who underwent surgical repair also had a cerebrovascular event, which may have been a complication of the dissection or surgery. Patient 5 had an anteroseptal myocardial infarction in the last trimester of pregnancy and prior to a type B aortic dissection postpartum. Patient 7 had a previous myocardial infarction that was treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty of the left anterior descending artery at the age of 41 years, two years before she presented with an aortic dissection.

Two women were hypertensive at the time of presentation and were admitted for evaluation of toxemia. Several days later, these women complained of chest, back or epigastric pain and were subsequently found to have thoracic aortic dissections. Another woman was diagnosed with postpartum pre-eclampsia. Two other women had a previous history of hypertension, but were not taking medication for hypertension during the pregnancy.

None of these women were diagnosed with an ACTA2 mutation prior to their dissections. Despite the fact that six of the women had a family history of aortic dissections, none of them were being monitored for aortic disease. Genetic testing of these women identified the following ACTA2 mutations: c.116G>A (p.Arg39His), c.115C>T (p.Arg39Cys), c.145A>G (p.Met49Val), c.445C>T (p.Arg149Cys), c.824G>C (p.Gly275Ala), and c.904T>G (p.Ser302Ala) (Table 1). Except for ACTA2 mutations resulting in p.Gly275Ala and p.Ser302Ala, the rest of the mutations have been previously reported in multiple individuals with thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections and other vascular diseases [Guo et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2009; Morisaki et al., 2009]. Gly275Ala and Ser302Ala alter highly conserved residues and were not found in in-house controls and the exome sequencing databases. The p.Gly275Ala substitution is predicted to be damaging by Polyphen-2 analysis. The p.Ser302Ala substitution is predicted to be benign; however, familial studies showed that this mutation was present in the proband (Patient 8) and her father who had a thoracic aortic dissection at the age of 45 years, and more recent brain imaging of the patient demonstrated typical features of cerebrovascular disease associated with ACTA2 mutations, i.e. mild narrowing of the supraclinoid internal carotid arteries and periventricular hyperdense lesions [Milewicz et al., 2010; Munot et al., 2012].

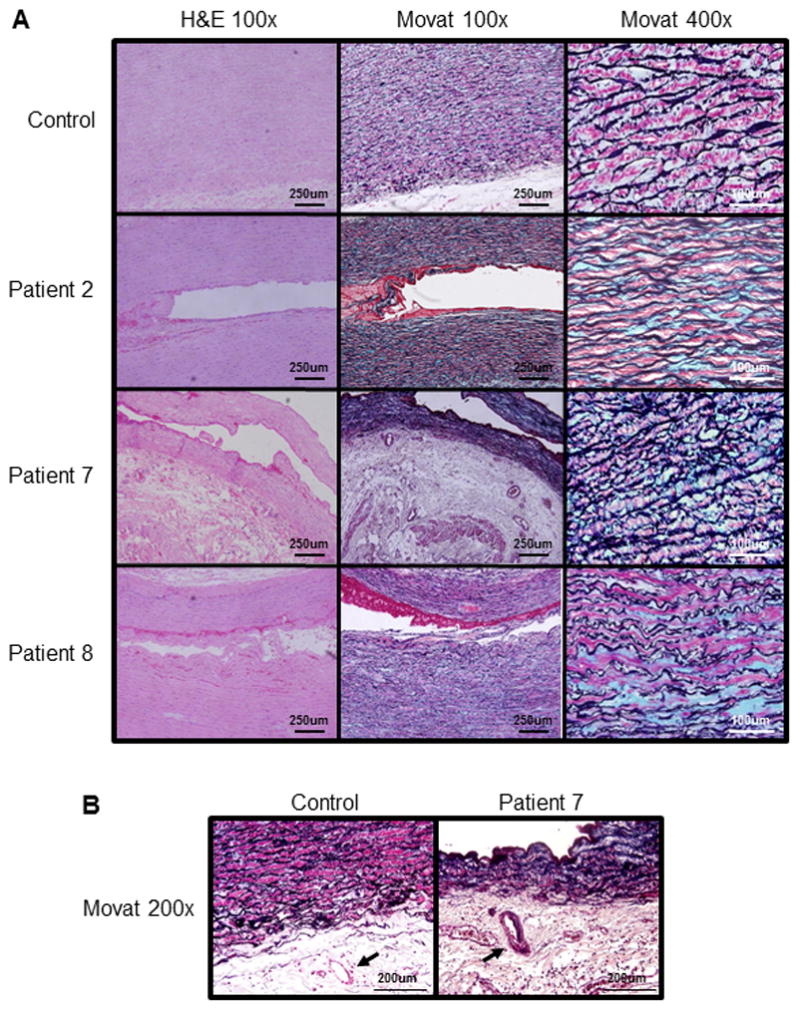

The ascending thoracic aortic pathology was reviewed for Patients 2, 7 and 8 (Figure 2A). The H&E stained aortas were significant for mild to moderate medial degeneration defined by loss of smooth muscle cells and elastic fibers, and proteoglycan accumulation in the medial layer of the aorta. Aorta from Patient 2 demonstrated little to no loss of smooth muscle cells and elastin fibers but had diffuse deposition of proteoglycans. Similarly, aorta from Patients 7 and 8 had significantly more proteoglycan deposition but also have elastic fiber fragmentation and loss of smooth muscle cells (Figure 2A). It has been previously reported that the arteries in the outer layer of the aorta (termed vasa vasorum) can be occluded or stenotic in patients with ACTA2 mutations, and stenosis of these arteries was also observed in one of the patients (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Aortic pathology of women with ACTA2 mutations and peripartum aortic dissections. (A) Compared with the control aorta, H&E and Movat staining of the aortic media from Patients 2, 7 and 8 showed mild medial degeneration characterized by focal proteoglycan accumulation (stained blue by Movat staining) and loss of SMCs and elastic fibers (stained black by Movat staining). (B) Movat staining demonstrated occlusion of vasa vasorum (arrow) in Patient 7 which is absent in the control.

DISCUSSION

Of the 53 women with ACTA2 mutations who had a total of 137 delivered pregnancies, only 8 women had an aortic dissection during pregnancy or postpartum (6% of pregnancies). The majority of these dissections were type A (6 out of 8), half of which were fatal. Only one woman had other vascular disease that occurred independent of the dissection, which was a myocardial infarct during the third trimester. Thus, the majority of women with ACTA2 mutations had pregnancies without aortic or vascular complications. These findings are similar to those reported for women with Marfan syndrome, in which 4–7% of pregnancies are complicated by either rapid aortic root enlargement or acute aortic dissections, including both type A and type B dissections [Lind and Wallenburg, 2001; Lipscomb et al., 1997; Pacini et al., 2009]. However, compared to the population-based frequency of peripartum dissections of 0.6% (2 of 346) [Nienaber et al., 2004], the frequency of peripartum aortic dissections in women with ACTA2 mutations is significantly greater (20%;8 of 39)

CT imaging revealed that three women in this series experienced type A dissections with minimal dilatation of the ascending aorta, with a type A dissection occurring at an aortic diameter of only 3.8 cm. There have been at least two reports of women with ACTA2 mutations and pregnancy related aortic dissections in the literature. Additionally, a 28-year-old woman with an ACTA2 p.Asp26Tyr substitution had a type A aortic dissection late in the pregnancy, and the aortic root diameter measured only 3.5 cm[Yoo et al., 2010].

Five of the women in this report were hypertensive at presentation or had a previous history of hypertension. Hypertension is an established risk factor for aortic dissections [Januzzi et al., 2004];[LeMaire and Russell, 2011]. We can speculate that hypertension and the increased intravascular volume of pregnancy can trigger aortic dissections at small aortic diameters in individuals with ACTA2 mutations. In addition, the aortic pathology indicated that these dissections occurred with minimal medial degeneration of the aorta. The common pathologic feature in these patients with acute dissections was increased proteoglycan accumulation in the medial layer of the aorta. Interestingly, accumulation of proteoglycans in the medial layer has been proposed to decrease tensile strength of the aorta and predispose to local delamination within the media that could help to propagate a dissection [Humphrey, 2013; Roccabianca et al., 2013].

Eight genes predisposing to thoracic aortic aneurysms and acute aortic dissections have been identified so far: ACTA2 (α-actin; MIM 102620), MYH11 (myosin heavy chain; MIM 160745), MYLK (myosin light chain kinase; MIM 600922), FBN1 (fibrillin; MIM 134797); TGFBR1 (transforming growth factor-beta receptor, type I; MIM 190181), TGFBR2 (transforming growth factor-beta receptor, type II; MIM 190182), SMAD3 (mothers against decapentaplegic, drosophila, homolog of, 3; MIM 603109) and TGFB2 (transforming growth factor, beta-2; MIM 190220) [Boileau et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2007; Lindsay et al., 2012; Loeys et al., 2006; Pannu et al., 2005; Regalado et al., 2011; van de Laar et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2006]. However, there are still many families with this condition in which the causative gene has not been identified. It is important to note that a subset of these genes mutations also cause additional features, such as the skeletal features in individuals with Marfan syndrome, but other gene mutations can predispose to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections without substantial syndromic features. Women with a personal and/or family history of thoracic aortic dissections should be evaluated for mutations in these known genes. If a causative gene mutation is not identified in the family, then women who are at risk of inheriting the genetic predisposition to aortic disease should undergo aortic imaging, preferably prior to pregnancy, and be carefully monitored for aortic disease whether or not aortic enlargement is present. Young women who experience aortic dissections during pregnancy should be assessed for gene mutations underlying the dissection, whether or not they have features of known syndromes such as Marfan syndrome.

The findings from women with ACTA2 mutations indicate that pregnancy is associated with an increased risk for ascending and descending thoracic aortic dissections with minimal aortic dilatation. This finding is based on a relatively small number of women in whom the diagnosis of ACTA2 mutation has not been made and no preventive measures were taken. It is not known how much of this risk can be altered with proper medical management, but the experience in patients with Marfan syndrome indicates the risk for rapid dilatation or dissection is low in carefully monitored women without significant aortic enlargement[Meijboom et al., 2005; Rossiter et al., 1995]. Women with ACTA2 mutations should be counseled about the risk of aortic dissection with pregnancy, including risk of dissection with minimal aortic dilatation. Blood pressure should be carefully monitored in these women, and treatment with β-adrenergic blocking agents considered. Prophylactic repair of the ascending aorta should be considered in women with ACTA2 mutation who are planning a pregnancy, in particular if the ascending aorta is significantly enlarged, and it is important to note that there is a risk for dissection involving the distal thoracic aorta even after replacement of the ascending aorta. Women with ACTA2 mutations should be advised to wear medical alert bracelets at all times that indicate a risk of thoracic aortic dissection, stroke and myocardial infarction. Consideration should be given to being near a tertiary care facility with 24-hour cardiovascular surgical coverage at least during the third trimester of pregnancy and a month postpartum. Physicians and patients should be aware of the symptoms of aortic dissections, as well as atypical presentations [Harris et al., 2011]. Pregnant women who present with these symptoms and report a genetic predisposition or family history of aortic aneurysm or dissection should raise a suspicion for aortic dissection and should be evaluated immediately with CT imaging.

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to patients involved in this study. The following sources provided funding for these studies: RO1 HL62594 (D.M.M.), P50HL083794-01 (D.M.M.), P01HL110869-01 (D.M.M.), UL1 RR024148 (University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston), Vivian L. Smith Foundation (D.M.M.), TexGen Foundation (D.M.M.), and the Richard T. Pisani Funds (D.M.M.).

References

- Boileau C, Guo DC, Hanna N, Regalado ES, Detaint D, Gong L, Varret M, Prakash SK, Li AH, d’Indy H, Braverman AC, Grandchamp B, Kwartler CS, Gouya L, Santos-Cortez RL, Abifadel M, Leal SM, Muti C, Shendure J, Gross MS, Rieder MJ, Vahanian A, Nickerson DA, Michel JB, Jondeau G, Milewicz DM. TGFB2 mutations cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections associated with mild systemic features of Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:916–921. doi: 10.1038/ng.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disabella E, Grasso M, Gambarin FI, Narula N, Dore R, Favalli V, Serio A, Antoniazzi E, Mosconi M, Pasotti M, Odero A, Arbustini E. Risk of dissection in thoracic aneurysms associated with mutations of smooth muscle alpha-actin 2 (ACTA2) Heart. 2011;97:321–326. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.204388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo DC, Pannu H, Papke CL, Yu RK, Avidan N, Bourgeois S, Estrera AL, Safi HJ, Sparks E, Amor D, Ades L, McConnell V, Willoughby CE, Abuelo D, Willing M, Lewis RA, Kim DH, Scherer S, Tung PP, Ahn C, Buja LM, Raman CS, Shete S, Milewicz DM. Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) lead to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1488–1493. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo DC, Papke CL, Tran-Fadulu V, Regalado ES, Avidan N, Johnson RJ, Kim DH, Pannu H, Willing MC, Sparks E, Pyeritz RE, Singh MN, Dalman RL, Grotta JC, Marian AJ, Boerwinkle EA, Frazier LQ, LeMaire SA, Coselli JS, Estrera AL, Safi HJ, Veeraraghavan S, Muzny DM, Wheeler DA, Willerson JT, Yu RK, Shete SS, Scherer SE, Raman CS, Buja LM, Milewicz DM. Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) cause coronary artery disease, stroke, and moyamoya disease, along with thoracic aortic disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Strauss CE, Eagle KA, Hirsch AT, Isselbacher EM, Tsai TT, Shiran H, Fattori R, Evangelista A, Cooper JV, Montgomery DG, Froehlich JB, Nienaber CA On Behalf of the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Investigators. Correlates of Delayed Recognition and Treatment of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection: the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE, Jr, Eagle KA, Hermann LK, Isselbacher EM, Kazerooni EA, Kouchoukos NT, Lytle BW, Milewicz DM, Reich DL, Sen S, Shinn JA, Svensson LG, Williams DM. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation. 2010;121:e266–e369. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181d4739e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffjan S, Waldmuller S, Blankenfeldt W, Kotting J, Gehle P, Binner P, Epplen JT, Scheffold T. Three novel mutations in the ACTA2 gene in German patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:520–524. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JD. Possible mechanical roles of glycosaminoglycans in thoracic aortic dissection and associations with dysregulated transforming growth factor-beta. J Vasc Res. 2013;50:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000342436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, Cooper JV, Smith DE, Fang J, Eagle KA, Mehta RH, Nienaber CA, Pape LA. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMaire SA, Russell L. Epidemiology of thoracic aortic dissection. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:103–113. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind J, Wallenburg HC. The Marfan syndrome and pregnancy: a retrospective study in a Dutch population. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay ME, Schepers D, Bolar NA, Doyle JJ, Gallo E, Fert-Bober J, Kempers MJ, Fishman EK, Chen Y, Myers L, Bjeda D, Oswald G, Elias AF, Levy HP, Anderlid BM, Yang MH, Bongers EM, Timmermans J, Braverman AC, Canham N, Mortier GR, Brunner HG, Byers PH, Van EJ, van LL, Dietz HC, Loeys BL. Loss-of-function mutations in TGFB2 cause a syndromic presentation of thoracic aortic aneurysm. Nat Genet. 2012;44:922–927. doi: 10.1038/ng.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb KJ, Smith JC, Clarke B, Donnai P, Harris R. Outcome of pregnancy in women with Marfan’s syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeys BL, Schwarze U, Holm T, Callewaert BL, Thomas GH, Pannu H, De Backer JF, Oswald GL, Symoens S, Manouvrier S, Roberts AE, Faravelli F, Greco MA, Pyeritz RE, Milewicz DM, Coucke PJ, Cameron DE, Braverman AC, Byers PH, De Paepe AM, Dietz HC. Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-beta receptor. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:788–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashini IS, Albazzaz SJ, Fadel HE, Abdulla AM, Hadi HA, Harp R, Devoe LD. Serial noninvasive evaluation of cardiovascular hemodynamics during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijboom LJ, Vos FE, Timmermans J, Boers GH, Zwinderman AH, Mulder BJ. Pregnancy and aortic root growth in the Marfan syndrome: a prospective study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:914–920. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewicz DM, Guo D, Tran-Fadulu V, Lafont A, Papke C, Inamoto S, Pannu H. Genetic Basis of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections: Focus on Smooth Muscle Cell Contractile Dysfunction. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008a;9:283–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewicz DM, Guo DC, Tran-Fadulu V, Lafont AL, Papke CL, Inamoto S, Kwartler CS, Pannu H. Genetic basis of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections: focus on smooth muscle cell contractile dysfunction. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008b;9:283–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewicz DM, Ostergaard JR, la-Kokko LM, Khan N, Grange DK, Mendoza-Londono R, Bradley TJ, Olney AH, Ades L, Maher JF, Guo D, Buja LM, Kim D, Hyland JC, Regalado ES. De novo ACTA2 mutation causes a novel syndrome of multisystemic smooth muscle dysfunction. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisaki H, Akutsu K, Ogino H, Kondo N, Yamanaka I, Tsutsumi Y, Yoshimuta T, Okajima T, Matsuda H, Minatoya K, Sasaki H, Tanaka H, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Morisaki T. Mutation of ACTA2 gene as an important cause of familial and nonfamilial nonsyndromatic thoracic aortic aneurysm and/or dissection (TAAD) Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1406–1411. doi: 10.1002/humu.21081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munot P, Saunders DE, Milewicz DM, Regalado ES, Ostergaard JR, Braun KP, Kerr T, Lichtenbelt KD, Philip S, Rittey C, Jacques TS, Cox TC, Ganesan V. A novel distinctive cerebrovascular phenotype is associated with heterozygous Arg179 ACTA2 mutations. Brain. 2012;135:2506–2514. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nienaber CA, Fattori R, Mehta RH, Richartz BM, Evangelista A, Petzsch M, Cooper JV, Januzzi JL, Ince H, Sechtem U, Bossone E, Fang J, Smith DE, Isselbacher EM, Pape LA, Eagle KA. Gender-related differences in acute aortic dissection. Circulation. 2004;109:3014–3021. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130644.78677.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacini L, Digne F, Boumendil A, Muti C, Detaint D, Boileau C, Jondeau G. Maternal complication of pregnancy in Marfan syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2009;136:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu H, Fadulu V, Chang J, Lafont A, Hasham SN, Sparks E, Giampietro PF, Zaleski C, Estrera AL, Safi HJ, Shete S, Willing MC, Raman CS, Milewicz DM. Mutations in transforming growth factor-beta receptor type II cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Circulation. 2005;112:513–520. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppas A, Shroff SG, Korcarz CE, Hibbard JU, Berger DS, Lindheimer MD, Lang RM. Serial assessment of the cardiovascular system in normal pregnancy. Role of arterial compliance and pulsatile arterial load. Circulation. 1997;95:2407–2415. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.10.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado ES, Guo DC, Villamizar C, Avidan N, Gilchrist D, McGillivray B, Clarke L, Bernier F, Santos-Cortez RL, Leal SM, Bertoli-Avella AM, Shendure J, Rieder MJ, Nickerson DA, Milewicz DM. Exome Sequencing Identifies SMAD3 Mutations as a Cause of Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection With Intracranial and Other Arterial Aneurysms. Circ Res. 2011;109:680–686. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard M, Callewaert B, Baetens M, Campens L, MacDermot K, Fryns JP, Bonduelle M, Dietz HC, Gaspar IM, Cavaco D, Stattin EL, Schrander-Stumpel C, Coucke P, Loeys B, De PA, De BJ. Novel MYH11 and ACTA2 mutations reveal a role for enhanced TGFbeta signaling in FTAAD. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.08.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roccabianca S, Ateshian GA, Humphrey JD. Biomechanical roles of medial pooling of glycosaminoglycans in thoracic aortic dissection. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10237-013-0482-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter JP, Repke JT, Morales AJ, Murphy EA, Pyeritz RE. A prospective longitudinal evaluation of pregnancy in the Marfan syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1599–1606. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90655-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman DI, Burton KJ, Gray J, Bosner MS, Kouchoukos NT, Roman MJ, Boxer M, Devereux RB, Tsipouras P. Life expectancy in the Marfan syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)80066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Laar IM, Oldenburg RA, Pals G, Roos-Hesselink JW, de Graaf BM, Verhagen JM, Hoedemaekers YM, Willemsen R, Severijnen LA, Venselaar H, Vriend G, Pattynama PM, Collee M, Majoor-Krakauer D, Poldermans D, Frohn-Mulder IM, Micha D, Timmermans J, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Willems PJ, Kros JM, Oei EH, Oostra BA, Wessels MW, Bertoli-Avella AM. Mutations in SMAD3 cause a syndromic form of aortic aneurysms and dissections with early-onset osteoarthritis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:121–126. doi: 10.1038/ng.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Guo DC, Cao J, Gong L, Kamm KE, Regalado E, Li L, Shete S, He WQ, Zhu MS, Offermanns S, Gilchrist D, Elefteriades J, Stull JT, Milewicz DM. Mutations in Myosin light chain kinase cause familial aortic dissections. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo EH, Choi SH, Jang SY, Suh YL, Lee I, Song JK, Choe YH, Kim JW, Ki CS, Kim DK. Clinical, pathological, and genetic analysis of a Korean family with thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections carrying a novel Asp26Tyr mutation. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2010;40:278–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Vranckx R, Khau Van KP, Lalande A, Boisset N, Mathieu F, Wegman M, Glancy L, Gasc JM, Brunotte F, Bruneval P, Wolf JE, Michel JB, Jeunemaitre X. Mutations in myosin heavy chain 11 cause a syndrome associating thoracic aortic aneurysm/aortic dissection and patent ductus arteriosus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:343–349. doi: 10.1038/ng1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]