Abstract

A number of phosphodiesterase 10A (PDE10) inhibitors are about to undergo clinical evaluation for their efficacy in treating schizophrenia. As phosphodiesterases are in the same signalling pathway as dopamine D2 receptors, it is possible that prior antipsychotic treatment could influence these enzyme systems in patients. Chronic, in contrast to acute, antipsychotic treatment has been reported to increase brain PDE10A levels in rodents. The aim of this study was to confirm these findings in a manner that can be translated to human imaging studies to understand its consequences. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning was used to evaluate PDE10A enzyme availability, after chronic haloperidol administration, using a specific PDE10A ligand ([11C]MP-10). The binding of [11C]MP-10 in the striatum and the cerebellum was measured in rodents and a simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) with cerebellum as the reference region was used to determine the binding potential (BPND). In rats treated chronically with haloperidol (2 mg kg−1 per day), there was no significant difference in PDE10A levels compared with the vehicle-treated group (BPND±s.d.: 3.57±0.64 versus 2.86±0.71). Following PET scans, ex vivo analysis of striatal brain tissue for PDE10A mRNA (Pde10a) and PDE10A enzyme activity showed no significant difference. Similarly, the PDE10A protein content determined by western blot analysis was similar between the two groups, contrary to an earlier finding. The results of the study indicate that prior exposure to antipsychotic medication in rodents does not alter PDE10A levels.

Introduction

Antipsychotic drugs mediate their effects by blocking dopamine D2 receptors and in doing so they increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels. The duration and amplitude of cyclic nucleotide signalling is regulated by cellular phosphodiesterases (PDEs) that break down cAMP.1,2 The brain expresses the most dense and diverse collection of PDEs in the body and the medium spiny neurons of the basal ganglia have the greatest density of PDEs as well as dopamine D2 receptors.3,4 As PDEs are at the heart of the striatal dopamine D2 signalling pathway, it is possible that chronic D2 receptor blockade due to antipsychotic medication could alter PDE levels in the brain.

The PDE10A subtype has recently been characterized and has quite a remarkable localization in the brain, being predominantly expressed in the basal ganglia in medium spiny neurons.5 Hence, it is a prime therapeutic target for schizophrenia. PDE10A is a dual-substrate PDE hydrolysing both cAMP and cyclic guanosine monophosphate but has higher affinity for cAMP.6 A study by Dlaboga et al7 reported a substantial increase in the level of PDE10A expression in rodent striatum following chronic antipsychotic treatment. In that study, chronic haloperidol and clozapine treatment increased striatal PDE10A protein expression by 118% and 62%, respectively, but acute administration had no effect. There are also several other instances where PDE levels have been influenced either by the disease process or by concurrent medication.8,9 An example in the CNS is the alteration of brain PDE4 iso-enzyme levels due to repeated treatment with antidepressants in the mouse.10

In preclinical models, inhibition of PDE10A is shown to have potential antipsychotic action.11,12 As a number of candidate PDE10A inhibitors are about to undergo clinical trials for the treatment of schizophrenia13 and if prior antipsychotic medication were to influence PDE10A levels in the brain, then there is a need to adjust dosing levels to accommodate such a change. Dose calculations are normally derived from preclinical models that have not been exposed to antipsychotic medication and from healthy human volunteers in Phase 1 trials.

Also, the method by which antipsychotics were administered (daily intraperitoneal injections) in the Dlaboga et al 7 study is not entirely consistent with clinical use (where a sustained threshold is maintained). Daily intraperitoneal injections in rodents lead to plasma levels that dip to a negligible level during a 24-h period as most antipsychotics have a half-life of 2–4 h in rodents, whereas the half-life of most antipsychotics in humans is usually 12–24 h.14 Hence, the present study was designed taking into consideration a delivery method (subcutaneous mini-osmotic pumps) that maintained constant plasma levels to evaluate the effect of chronic antipsychotic treatment on striatal PDE10A levels in rodents.

Extensive efforts are underway to develop radiotracers to noninvasively image PDEs especially PDE10A using positron emission tomography (PET) and the challenge has been to achieve subtype and splice variant selectivity.15,16 In our study, a PDE10A-specific ligand ([11C]MP-10)17 was used to evaluate PDE10A enzyme availability after chronic haloperidol administration, primarily as a translational tool for human imaging. Ex vivo tissue analysis for mRNA, protein levels and enzyme activity were also carried out to substantiate the PET findings. mRNA levels of four target genes (Pde10a, Pde1b, dopamine D2 receptor and neurotensin) were chosen as changes in expression of these genes due to chronic antipsychotic treatment have been reported.7,18,19 Western blotting was carried out to quantify striatal protein levels. Total and PDE10A-specific cAMP PDE activity in striatum were measured in enzymatic assays to assess potential changes in PDE activity of PDE10A or other PDEs.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River, Kent, UK), weighing 308–456 g, housed under a 12- h light/dark cycle (0700 hours lights on) with food and water available ad libitum were allowed to habituate for at least 7 days before performing experimental procedures. The temperature and relative humidity settings at the animal house were 19–21 °C and 40–55%, respectively. At the imaging facility, the temperature and relative humidity settings were 19–23 °C and 45–65%, respectively. The procedures used in the present study were approved by the Animal Ethical Review Committee of Imperial College London, UK and all experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, UK, 1986.

Experimental design

The experiment was carried out in two phases. The first phase (n=7) was a pilot to determine an adequate sample size that would detect a difference of at least 20% of the primary PET parameter BPND (binding potential) with >80% power (α=0.05, in a two-tail test) in normal rats at baseline conditions. In the second phase, rats were divided into two groups (n=6 per group) and they received either a common vehicle (β-hydroxypropylcyclodextrin, 20% w/v, acidified by ascorbic acid, to pH 6) or 2 mg kg−1 per day haloperidol (all chemicals were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) via subcutaneous osmotic mini-pumps (Alzet® Model 2ML4, 28 days; Alzet, Cupertino, CA, USA) for 3 weeks. The dose of haloperidol was at the higher range of clinical dosing based on receptor occupancy studies using our prior results with osmotic mini-pumps.14,20 Osmotic mini-pumps were implanted under aseptic conditions on the back flank under isoflurane general anaesthesia (induction 5% isoflurane with oxygen flow rate at 5 l min−1 and during anaesthetic maintenance, 1.5–2.5% isoflurane was administered with oxygen at a flow rate of 2–3 l min−1, IsoFlo, Abbott Lab Ltd., Kent, UK). The analgesic carprofen (Rimadyl, Zoetis UK Ltd., London, UK) was administered to each rat at a dose of 5 mg kg−1 before the start of surgery. The animals were monitored and body weights recorded at appropriate intervals as part of post-operative care.

PET-computed tomography (CT) scanning was carried out on day 21 following implantation of the osmotic pumps. Vacuous chewing movements (oral dyskinesias) were evaluated by placing each rat on a small elevated box and recording the number of vacuous chewing movements over a 2-min period, before anaesthetizing them for PET-CT scanning.21 Under isoflurane anaesthesia, the tail vein and artery of each rat were cannulated for tracer injection and blood sampling, respectively. Blood (up to 0.75 ml) was collected before the start of PET scan. After the completion of PET scan, each animal was killed using a lethal dose of intravenous pentobarbitone (Euthasol Vet, Le Vet B.V., Oudewater, The Netherlands). The striatal brain tissue was immediately dissected and stored at −80 °C until analysis could be performed. Plasma haloperidol was measured commercially (St George's, University of London, Tooting, UK) using an analytical technique that used a combination of liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Statistical comparisons between the two treatment groups were performed using a two-tailed Welsh t-test unless otherwise mentioned.

PET-CT scanning

In both phases of the experiment, dynamic PET scans using the Siemens Inveon DPET/MM PET-CT scanner (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) were acquired under Isoflurane general anaesthesia (1.5–2.5% isoflurane with oxygen at a flow rate of 2–3 l min−1). Each rat was secured on a bed comprising of ear bars, an anaesthetic delivery nose cone and a tooth bar in the scanner. The head was first placed in the field-of-view of the CT scanner and a 20-min CT scan was performed to collect data for attenuation correction and provide structural information. Subsequently, the head was positioned in the field-of-view of the PET scanner. [11C]MP-10 was prepared by N-alkylation of the precursor GSK2375586 using cyclotron-produced [11C]methyl iodide at IMANOVA as previously described.17 In the pilot phase a 60-min dynamic PET scan was performed, whereas in the second phase, the majority of the animals underwent a 90-min acquisition following intravenous bolus administration (specific activities 61.64–141.26 GBq μmol−1) of [11C]MP-10. The body temperature was maintained throughout the scan using a heating mat and lamp, and the temperature was monitored using a rectal probe. The respiration rate was monitored using a respiration pad.

Conservative striatal and cerebellum regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn in the PET images registered to their corresponding CT images using an approach that balanced partial volume effects and the number of counts within the ROI. The striatum was drawn within +2.28 to −1.20 mm anterioposterior to the bregma and anterior to the interaural coordinates of 11.28–7.80 mm guided by the CT images with reference to the Paxinos Rat Atlas.22 Cerebellum ROIs were drawn within 9.96–13.20 mm posterior to the bregma and 0.96–4.20 mm posterior to the interaural line of the atlas avoiding the vermis. Volumes of ROIs for the striatum and cerebellum were maintained across scans. The ROIs were applied to the dynamic PET data to generate the corresponding time–activity curves (TACs) for the striatum and cerebellum. Tissue radioactivity concentrations were normalized for the radioactive dose injected and for the animal's body mass giving standard uptake values ((kBq ml−1 tissue)/(kBq g−1 body mass)) with the assumption that 1 cm3 equals 1 g of tissue. A simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) with the cerebellum as the reference region was applied to the TACs to generate a striatal BPND value for each scan using the first 60 min of dynamic data for each scan.23

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was purified from dissected striata using the NucleoSpin RNA and Protein kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). A measure of 1 μg of each sample based on NanoDrop measurements (NanoDrop products, Wilmington, DE, USA) was used for the first strand cDNA synthesis using random hexamer primers and the TaqMan reverse transcription reagents according to the manufacturer (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Pde10a, Pde1b, D2 receptor and Neurotensin (Nts) striatal mRNA were measured.

Quantitative PCR primers were designed by the Primer Blast algorithm (Supplementary Table S1)24 and validated against Mouse Universal Reference Total RNA from Clontech Laboratories (Mountain View, CA, USA). qPCR was performed on a Bio-Rad C1000 Touch thermal cycler with a CFX384 optical reaction module using SsoFastTM EvaGreen Supermix according to the manufacturer's instruction (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) starting with 95 °C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 10 s. Samples were run in technical duplicates and mean quantification cycle (Cq) values were used for further calculations. Eight reference genes (Alas2, Actb, B2m, Tbp, G6pd, Ppia, Trfc and Ubc) were included and the three most optimal genes (Ppia, Trfc and Ubc) based on the geNorm algorithm (Supplementary Figure S1)25 were used for geometric normalization; however, all eight of the analysed reference genes were fit for normalization as indicated by the relative low variation based on M values (Supplementary Figure S1C). Data were normalized to vehicle control and significant differences were based on two-tailed Welsh t-tests.

Western blotting

Striatal lysate for western blotting and PDE activity measurement was prepared as follows: dissected striata were homogenized with a Polytron PT 1200E homogenizer (Kinematica AG, Luzern, Switzerland) in 700 μl cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100 and 1% complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Samples were left on ice for 15 min, centrifuged for 30 min at 20 000 g at 4 °C and the supernatant (striatal lysate) was removed for further testing and frozen in aliquots on dry ice. Protein content of each preparation was measured by Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA); the protein concentration varied from 2.6 to 4.0 μg μl−1.

Total protein (30 μg) of each striatal lysate was mixed with LDS loading buffer (NP0007, Life Technologies) supplemented with 4 M urea and were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 4–12% bis–tris gel (Life Technologies). Rainbow molecular weight markers (Amersham Biosciences, GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Brondby, Denmark) were included. Immunoblotting was carried out using standard methods with anti-PDE10A C-17, SC66502 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) diluted 1:1500 and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) AB9484 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:5000 as primary antibodies. IRDye 800CW donkey anti-goat antibody 926–32214 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) diluted 1:20 000 and IRDye 680 goat anti-mouse antibody 926–32220 (LI-COR Biosciences) diluted 1:20 000 were used as secondary antibodies. PDE10A signal was quantified in the 800 nM channel and GAPDH in the 700 nM channel on an LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Western Blot Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Differences in intensities between vehicle- and haloperidol-treated rats were evaluated by the two-tailed Welsh t-test.

PDE activity measurement

Total and PDE10A PDE activity was assessed on aliquotes of striatal lysate prepared for western blotting. cAMP PDE activity of striatal lysate was measured using a scintillation proximity assay (SPA)-based method as previously described.26,27 Lysate (0.05 μl) was used in each 60 μl reaction, which resulted in ≈20% hydrolysis of tritiated cAMP at the end point. Each measurement was performed in quadruplicates and the mean was used for further comparison. Total PDE activity was assessed by subtracting counts per minute for wells with striatal lysate with the background measured as counts per minute in wells without added lysate. PDE10A activity was assessed by subtracting total PDE activity with PDE activity measured in the presence of 250 nM of the selective PDE10A inhibitor MP-10, which has a reported IC50 for PDE10A of 0.18 nM.11 Differences in activity between vehicle- and haloperidol-treated rats were evaluated on the basis of two-tailed Welsh t-test.

Results

PET scanning

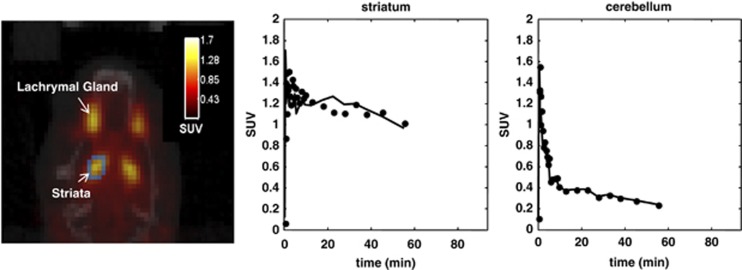

In the first phase of the experiment, high accumulation of radioactivity was seen in the striatum and lacrimal glands following [11C]MP-10 administration (Figure 1). Striatal TACs for each subject showed an initial high uptake of radioactivity, which was retained over the time-course of the scan (Figure 1). The cerebellum TACs showed a similar initial uptake but more rapid decline in radioactivity concentrations over the same period due to low levels of PDE10A in this region (Figure 1). SRTM with the cerebellum as the reference region was applied to the TACs to generate a striatal BPND value for each scan. The cerebellum was chosen as the reference region given its very low PDE10A protein expression and supported by negligible levels of displaceable binding of [11C]MP-10 due to cold MP-10 administration in baboons.5,17,28 The average BPND for seven animals was calculated as 2.8±0.6 (mean±s.d.). Using these results, the statistical power to measure a 20% change of BPND using 12 animals (6 in each group, assuming variances in the two groups would be similar) for the next phase was determined to be >80% (two tail Student's t-test).

Figure 1.

A representative positron emission tomography scan of the head of a rat injected intravenously with [11C]MP-10 and time–activity curves of standard uptake values from its striatum and cerebellum regions.

In the second phase, animals tolerated the drug well and there was no significant change in body weight between the two groups. In the drug-treated arm, one animal stopped breathing midway through the scan and could not be revived but with the exception of BPND, all other parameters were recorded for that animal and included in the data analysis. There was also no statistically significant difference in BPND between the two groups after 3 weeks of treatment (Table 1). The average injected mass of [11C]MP-10 (mean±s.d.) was not significantly different between the groups (vehicle 0.30±0.08 versus haloperidol 0.33±0.12 μg kg−1, P=0.71). The average plasma level of haloperidol in the drug-treated group measured after 21 days of treatment on the day of PET scanning was 19.9±5.13 ng ml−1 (mean±s.d.). Rats in the haloperidol group showed statistically increased vacuous chewing movements compared with the vehicle-treated group (Table 1). The plasma levels of haloperidol and vacuous chewing behaviour indicate that the drug was administered as intended via osmotic mini-pumps.

Table 1. Striatal [11C]MP-10 binding potential, plasma drug level and VCM due to haloperidol treatment.

| Treatment (n=6 in each group) | Binding potential (BPND) | Haloperidol plasma levels (ng ml−1) | VCM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 3.57±0.64 | b.l.d. | 1.33±0.52 |

| Haloperidol | 2.86±0.71a | 19.9±5.93 | 8.17±2.93b |

Abbreviations: b.l.d., below level of detection (<1 ng ml−1); VCM, vacuous chewing movement.

Values are presented as mean+s.d.

Not statistically significant in comparison to the vehicle group (Welsh t-test statistic P=0.12).

Statistically significant compared with the vehicle group (Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test U=36, P<0.001).

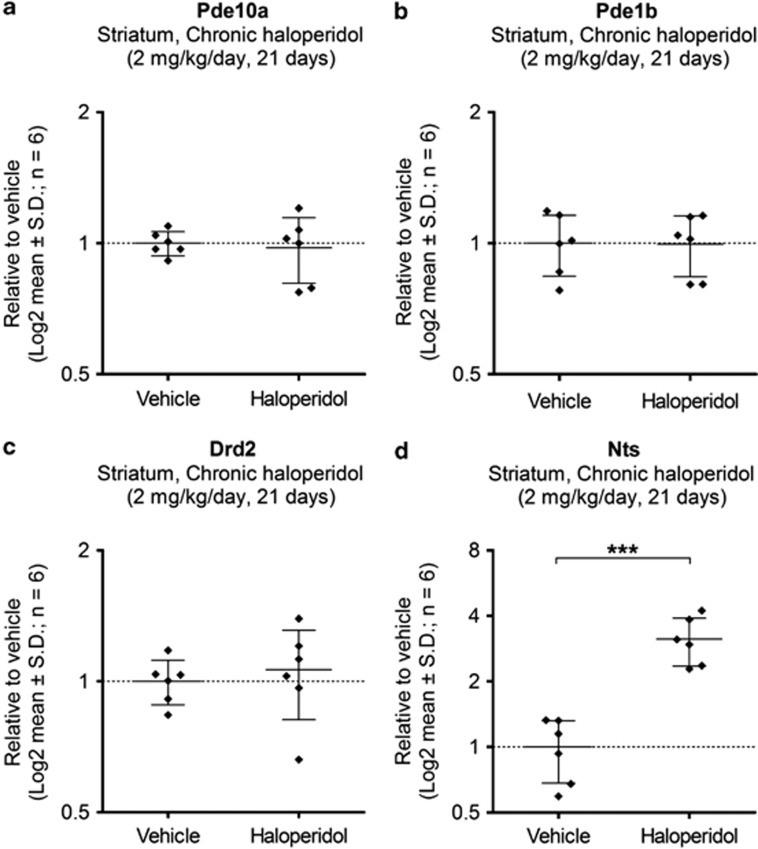

Pde10a mRNA levels—qPCR

The mRNA levels of Pde10a and other selected transcripts in the striatum were assessed by qPCR (Figure 2). There was no significant change in Pde10a mRNA levels in the striatum after 21 days of chronic haloperidol treatment compared with vehicle (P=0.669). Furthermore, no significant changes were identified in Pde1b mRNA levels (P=0.975) or dopamine D2 receptor (Drd2) mRNA levels (P=0.728), whereas a significant increase in Nts mRNA levels was observed (P<0.0001).

Figure 2.

mRNA levels in the striatum after treatment with haloperidol in comparison to vehicle-treated rats: (a) phosphodiesterase 10A (Pde10a); (b) phosphodiesterase 1B (Pde1b); (c) dopamine D2 receptor (Drd2); and (d) neurotensin (Nts). ***P=0.0001 compared with vehicle.

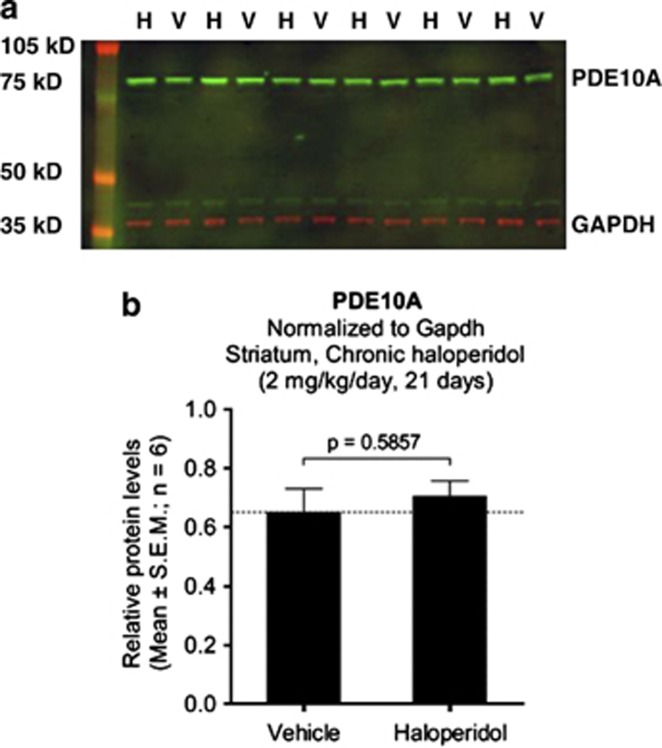

PDE10A protein levels—western blots

Effect of haloperidol treatment on striatal PDE10A protein levels were assessed by western blotting (Figure 3a). PDE10A was measured simultaneously with GAPDH for normalization using the LI-COR Odyssey Western Blot Infrared Imaging system. There was no significant difference in GAPDH-normalized PDE10A expression in vehicle- and haloperidol-treated groups (Figure 3b). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the absolute PDE10A expression between the two groups (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of haloperidol treatment on the striatal PDE10A protein levels assessed by western blotting. (a) Two-colour western blot with striatal lysate from the six haloperidol (H)- and six vehicle (V)-treated rats loaded in alternate wells. PDE10A (green) and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; red) were simultaneously measured in the 800- and the 700-nm channels, respectively, using the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Western Blot Imaging System. (b) There was no significant difference in GAPDH-normalized PDE10A expression in the vehicle- and haloperidol-treated groups.

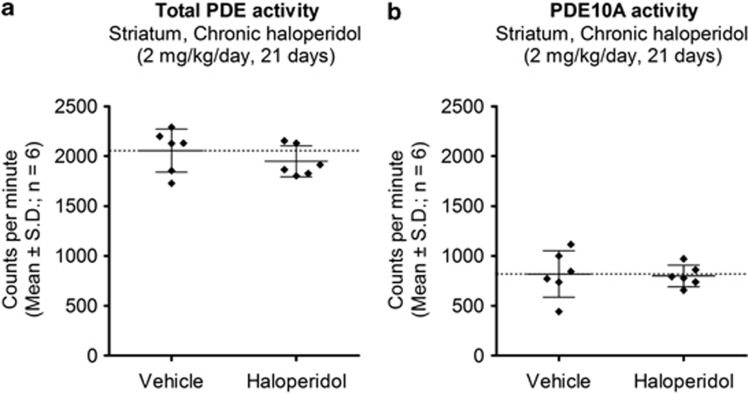

Total and PDE10A PDE enzyme activity

The total cAMP PDE activity in striatal lysates was measured as the amount of conversion of [3H]cAMP to [3H]AMP in the presence of a fixed amount of striatal lysate (Figure 4a). It was not significantly different between haloperidol- and vehicle-treated rats (P=0.35). PDE10A-specific activity was assessed by inhibiting total cAMP PDE activity in striatal lysates with 250 nM of the selective PDE10A inhibitor MP-10. PDE10A constituted just under half of the total PDE activity in striatal lysate of vehicle-treated animals (Figure 4b). There was no significant difference in striatal PDE10A activity between haloperidol- and vehicle-treated rats (P=0.86).

Figure 4.

Effect of haloperidol treatment on striatal phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymatic activity. (a) Total PDE activity and (b) PDE10A activity indicating no effect of drug treatment.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to verify the earlier observation that antipsychotic treatment induces elevation of striatal PDE10A levels.7 Antipsychotic drug action on the dopaminergic system is of a temporal nature. In the initial phase, blockade of presynaptic dopamine D2 receptors leads to a surge of dopamine in the synapse and this could lead to activation of the postsynaptic D1 receptors while postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors are blocked.29 Both these actions lead to increase in intracellular cAMP.30 The surge of dopamine due to presynaptic blockade rapidly desensitizes presynaptic dopamine receptors in rodents and this is followed by sustained postsynaptic blockade with synaptic dopamine reaching baseline levels.31 Over time, the postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors are known to upregulate and become supersensitive owing to chronic blockade both in rodents and in humans.31,32 Hence, both intracellular cAMP levels as well as PDE activity could vary depending on the duration of the treatment.

The present experiment was performed in the later phase guided by previous experimentation with chronic antipsychotic dosing in rodents.31 After 3 weeks of chronic haloperidol treatment in rodents, the system stabilizes and is ideal for measurements that reflect a chronic phase of antipsychotic treatment.31 The PET imaging results showed no evidence of PDE10A enzyme elevation in the whole rodent striatum. The radiotracer ([11C]MP-10) is a selective and potent PDE10A inhibitor and has shown good brain penetration and regional binding in rhesus monkey.12,33 The observed kinetics in rats was consistent with those previously observed for MP-10 in primates with rapid washout in cerebellum and prolonged uptake in the striatum. In our data analysis, we quantified [11C]MP-10 binding using a SRTM, a technique that has been previously validated for quantification of this tracer in primates.17 Good model fits were obtained to the rat striatal data using SRTM. There was no evidence of any alteration in cerebellum levels between groups as assessed by changes in their standard uptake values consistent with the cerebellum as a valid reference region.

Very few transcriptomic studies have used appropriate antipsychotic doses or a chronic dosing strategy that mimics clinical reality and hence, there is very little concurrence in their striatal transcriptomic profiles.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 Girgenti et al.19 have used haloperiodol deconate (a long-acting form of haloperidol) as a depot and this study is the closest to being clinically relevant. They identified Nts as the most robustly upregulated mRNA in rats injected with haloperidol deconate (21 mg kg−1), once weekly, for 4 weeks in a microarray experiment followed by secondary confirmation by in situ hybridization of gene expression.19 A number of previous reports have reported this and even suggest antipsychotic action to be mediated by this neuropeptide system and hence Nts was chosen in this study.40, 41, 42 The direct target of haloperidol, dopamine D2 receptor, and Pde10a and Pde1b mRNA as reported by Dlaboga et al.7 were also tested. Dopamine D2 receptor mRNA upregulation has previously been reported to be changed by chronic haloperidol treatment, although reports are mixed.18,19,31 The lack of dopamine D2 receptor mRNA may suggest that high and sustained levels of D2 receptor blockade may not have been achieved but high levels of drug in plasma, increased levels of Nts mRNA and high vacuous chewing movement scores in the haloperidol group are indicators of high and sustained D2 receptor blockade. We did not find any change in Pde10a, Pde1b or D2 receptor mRNA levels in the striatum after chronic haloperidol treatment; however, we observed a highly significant increase in the striatal Nts mRNA levels indicating transcriptional activation due to antipsychotic treatment.

In our study, western blot and PET studies did not indicate any change in PDE10A protein content due to drug treatment and similarly Pde10a mRNA levels were unchanged. These results contradict the previous study by Dlaboga et al.7 and differences in dosing patterns of the antipsychotic drug could be a cause. However, the dosing strategy adopted in this study is closer to clinical reality and hence, our study is likely to be more predictive for patients chronically treated with antipsychotic medication.

PDEs are regulated through a variety of transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms in response to hormonal, environmental or pharmacological stimuli.2 The complex PDE machinery in cells and the way it maintains cellular homoeostasis is still at a nascent stage of our understanding.43 There exists a delicate balance between synthesis and degradation of cyclic nucleotides and hence, a subtle change in the ability of PDEs to break down cyclic nucleotides can have a significant effect in cell signalling.44 Their subcellular localization can also have a significant effect in cell signalling.45 In the case of PDE10A, it has been shown that the main PDE10A isoform is palmitoylated and that phosphorylation of PDE10A by protein kinase A can interfere with palmitoylation.46 Furthermore, PDE10A has a high-affinity cAMP binding site in its N-terminal GAF-domain, but the effect of cAMP binding to this site is unclear.26,47 We have observed change neither in the accessibility of MP-10 binding sites in vivo nor in the striatal PDE10A enzymatic activity ex vivo owing to haloperidol treatment, but ex vivo experimentation may not have captured the intricacies in native tissue.

The other caveats of this study include: (i) both PET as well as ex vivo studies were performed using the entire striatum and there could be unrecognized regional variation; (ii) there are reports of two brain penetrating radiometabolites of [11C]MP-10 in rodents, albeit in low quantities, and suboptical kinetics of the radiotracer in the striatum that could limit the PET interpretation of PDE10A levels and hence, a combination of methods was used in this study;33 (iii) isoflurane anaesthesia can affect regional cerebral blood flow, metabolic rates and neurotransmission, which could affect tracer kinetics, and this remains a limitation in this study;48 (iv) the consequences of drug withdrawal have not been studied; and (v) the study is limited to a single antipsychotic, measured at one time point during the course of treatment.

In any case, the results indicate that striatal PDE10A expression is not altered due to chronic antipsychotic treatment. A proof of concept study by Pfizer in which MP-10 (PF-2545920) was evaluated for its antipsychotic efficacy resulted in negative results.49 On the basis of the findings in the present study, it is unlikely that altered PDE10A levels in the patients due to prior exposure to antipsychotics undelie the negative result. However, we also have no knowledge on the baseline PDE10A expression levels in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. As a next step, we are conducting human PET imaging experiments to answer these questions. The result of this study will help guide clinical trials not only for schizophrenia therapeutics but also for other neuropsychiatric disorders, especially Huntington's disease, where concomitant antipsychotic use is prevalent.49

Acknowledgments

The study received funding from H. Lundbeck A/S and we acknowledge the salary support of S Kapur and SN from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London. We acknowledge the support of Dr Christophe Plisson and Dr Jan Passchier of the Radiochemical Sciences division of Imanova towards synthesis of the tracer and its initial characterization. This study was supported by H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Denmark and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London.

S Kapur has received grant support from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline and has served as consultant and/or speaker for AstraZeneca, Bioline, BMS-Otsuka, Eli Lilly, Janssen (J&J), Lundbeck, NeuroSearch, Pfizer, Roche, Servier and Solvay Wyeth in the past three years. SA, S-PT, CS, RNG and EAR are all employees of Imanova Ltd. RNG has also served as consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, UCB and Roche in the past three years. EAR has also served as consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, BioTie, Takeda and AbbVie. JN, JBL and TBS are employees of Lundbeck A/S. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Conti M, Beavo J. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menniti FS, Faraci WS, Schmidt CJ. Phosphodiesterases in the CNS: targets for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:660–670. doi: 10.1038/nrd2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Hersch SM, Rye DB, Sunahara RK, Niznik HB, Kitt CA, et al. Localization of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8861–8865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskran TM, Morton D, Menniti FS, Adamowicz WO, Kleiman RJ, Ryan AM, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of phosphodiesterase 10A in multiple mammalian species. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1205–1213. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A6930.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishige K, Kotera J, Michibata H, Yuasa K, Takebayashi S, Okumura K, et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel human phosphodiesterase that hydrolyzes both cAMP and cGMP (PDE10A) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18438–18445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlaboga D, Hajjhussein H, O'Donnell JM. Chronic haloperidol and clozapine produce different patterns of effects on phosphodiesterase-1B, -4B, and -10A expression in rat striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb AL, Robertson HA. Role of phosphodiesterases in neurological and psychiatric disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhang HT, O'Donnell JM. Phosphodiesterases in the central nervous system: implications in mood and cognitive disorders. Handbook Exp Pharmacol. 2011;204:447–485. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17969-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlaboga D, Hajjhussein H, O'Donnell JM. Regulation of phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) expression in mouse brain by repeated antidepressant treatment: comparison with rolipram. Brain Res. 2006;1096:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CJ, Chapin DS, Cianfrogna J, Hajos M, Harms JF, Harms JF, et al. Preclinical characterization of selective phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitors: a new therapeutic approach to the treatment of schizophrenia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:681–690. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grauer SM, Pulito VL, Navarra RL, Kelly MP, Kelley C, Graf R, et al. Phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitor activity in preclinical models of the positive, cognitive, and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:574–590. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehler J, Kilburn JP. Patented PDE10A inhibitors: novel compounds since 2007. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;19:1715–1725. doi: 10.1517/13543770903431050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, VanderSpek SC, Brownlee BA, Nobrega JN. Antipsychotic dosing in preclinical models is often unrepresentative of the clinical condition: a suggested solution based on in vivo occupancy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:625–631. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres JI, De Angelis M, Alcazar J, Celen S, Bormans G. Recent advances in positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers for imaging phosphodiesterases. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12:1224–1236. doi: 10.2174/156802612800672853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JP, Cumming P, Vasdev N. PET radiopharmaceuticals for probing enzymes in the brain. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;3:194–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plisson C, Salinas C, Weinzimmer D, Labaree D, Lin SF, Ding YS, et al. Radiosynthesis and in vivo evaluation of [(11)C]MP-10 as a positron emission tomography radioligand for phosphodiesterase 10A. Nuclear Med Biol. 2011;38:875–884. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga T, Ohara K, Natsukari N, Fujita M. Dopamine D2-receptor mRNA level in rat striatum after chronic haloperidol treatment. Neurosci Res. 1991;12:440–445. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(91)90075-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgenti MJ, Nisenbaum LK, Bymaster F, Terwilliger R, Duman RS, Newton SS. Antipsychotic-induced gene regulation in multiple brain regions. J Neurochem. 2010;113:175–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Zipursky R, Roy P, Jones C, Remington G, Reed K, et al. The relationship between D2 receptor occupancy and plasma levels on low dose oral haloperidol: a PET study. Psychopharmacology. 1997;131:148–152. doi: 10.1007/s002130050277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrone P, Remington G, Kapur S, Nobrega JN. The relationship between dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and the vacuous chewing movement syndrome in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;165:166–171. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C.The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 6th edn. Academic Press: London, UK; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. NeuroImage. 1996;4:153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes Genome Biol 20023RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthiesen K, Nielsen J. Binding of cyclic nucleotides to phosphodiesterase 10A and 11A GAF domains does not stimulate catalytic activity. Biochem J. 2009;423:401–409. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthiesen K, Nielsen J. Cyclic AMP control measured in two compartments in HEK293 cells: phosphodiesterase K(M) is more important than phosphodiesterase localization. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger TF, Bartlett B, Coskran TM, Culp JS, James LC, Krull DL, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of PDE10A in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2003;985:113–126. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Bunney BS. Acute effects of typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs on the release of dopamine from prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and striatum of the rat: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem. 1990;54:1755–1760. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacological Rev. 2011;63:182–217. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaha AN, Seeman P, Stewart J, Rajabi H, Kapur S. ‘Breakthrough' dopamine supersensitivity during ongoing antipsychotic treatment leads to treatment failure over time. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2979–2986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5416-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen F, Cross AJ, Crow TJ, Longden A, Poulter M, Riley GJ, et al. Increased dopamine-receptor sensitivity in schizophrenia. Lancet. 1978;2:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Fan J, Li S, Jones LA, Cui J, Padakanti PK, et al. Radiosynthesis and in vivo evaluation of [11C]MP-10 as a PET probe for imaging PDE10A in rodent and non-human primate brain. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:1666–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong VZ, Young LT, Mishra RK. cDNA array reveals differential gene expression following chronic neuroleptic administration: implications of synapsin II in haloperidol treatment. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1533–1539. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasulo WH, Hemby SE. Time-dependent changes in gene expression profiles of midbrain dopamine neurons following haloperidol administration. J. Neurochem. 2003;87:205–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EA, George RC, Danielson PE, Nelson PA, Warren AJ, Lo D, et al. Antipsychotic drug treatment alters expression of mRNAs encoding lipid metabolism-related proteins. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:983–993. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald ML, Eaton ME, Dudman JT, Konradi C. Antipsychotic drugs elevate mRNA levels of presynaptic proteins in the frontal cortex of the rat. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan CE, Chetcuti AF, Schofield PR. Coregulation of genes in the mouse brain following treatment with clozapine, haloperidol, or olanzapine implicates altered potassium channel subunit expression in the mechanism of antipsychotic drug action. Psychiatr Genet. 2008;18:226–239. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283053019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheux J, Ethier I, Rouillard C, Levesque D. Induction patterns of transcription factors of the nur family (nurr1, nur77, and nor-1) by typical and atypical antipsychotics in the mouse brain: implication for their mechanism of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:460–473. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.080184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE, Lynch AM, Aravagiri M, Nemeroff CB, Owens MJ. Chronic haloperidol-induced changes in regional dopamine release and metabolism and neurotensin content in rats. Brain Res. 1995;704:202–209. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant KM, Dobie DJ, Filloux FM, Totzke M, Aravagiri M, Dorsa DM. Effects of chronic haloperidol and clozapine treatment on neurotensin and c-fos mRNA in rat neostriatal subregions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:460–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B, Nemeroff CB. Further studies on the modulation of regional brain neurotensin concentrations by antipsychotic drugs: focus on haloperidol and BMY 14802. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:348–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AC, Cooper DM. Layers of organization of cAMP microdomains in a simple cell. Biochem Soc Transact. 2006;34:480–483. doi: 10.1042/BST0340480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beis I, Newsholme EA. The contents of adenine nucleotides, phosphagens and some glycolytic intermediates in resting muscles from vertebrates and invertebrates. Biochem J. 1975;152:23–32. doi: 10.1042/bj1520023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson TJ. Cell regulation: determined to signal discrete cooperation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charych EI, Jiang LX, Lo F, Sullivan K, Brandon NJ. Interplay of palmitoylation and phosphorylation in the trafficking and localization of phosphodiesterase 10A: implications for the treatment of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9027–9037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1635-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross-Langenhoff M, Hofbauer K, Weber J, Schultz A, Schultz JE. cAMP is a ligand for the tandem GAF domain of human phosphodiesterase 10 and cGMP for the tandem GAF domain of phosphodiesterase 11. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2841–2846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstrup AK, Smith DF. Anaesthesia for positron emission tomography scanning of animal brains. Lab Anim. 2013;47:12–18. doi: 10.1258/la.2012.011173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehler J. Phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitors: a 2009–2012 patent update. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23:31–45. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.739157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.