Abstract

This paper presents a review of the literature, summarizes current initiatives, and provides a heuristic for assessing the effectiveness of a range of IRB collaborative strategies that can reduce the regulatory burden of ethics review while ensuring protection of human subjects, with a particular focus on international research. Broad adoption of IRB collaborative strategies will reduce regulatory burdens posed by overlapping oversight mechanisms and has the potential to enhance human subjects protections.

Keywords: Institutional Review Board, Research Ethics Board, International research, Multinational research, Research partnership

Agencies in the United States and elsewhere have begun to emphasize the importance of streamlining ethics review in order to facilitate research (OHRP et al. 2005; FDA 2006; OHRP et al. 2006; Philippine Council for Health Research and Development 2006; College of Public Health Sciences and the Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Subjects, Health Sciences Group, Chulalongkorn University 2010; Pittman 2006; Cave & Holm 2002; Al-Shahi 2005). In its July 2011 Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM), the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) identified a streamlined approach to multisite review as both desirable and necessary to avoid duplication of effort and eliminate unnecessary delay (DHHS 2011; Emanuel and Menikoff 2011). The ANPRM calls for domestic, multi-site studies to have a single Institutional Review Board (IRB) of record; additional reviews by other participating sites, while not discouraged, would not be required for regulatory compliance. The ANPRM stipulates that this requirement would not apply to multinational research, largely because of the indispensable and widely accepted need for host-country input.

Not surprisingly, comments on the proposed policy suggest that many IRBs find the notion of a single IRB of record unacceptable, for many reasons (Bartlett 2012). Our purpose here is not to review and comment on the strengths and weaknesses of this proposal. In this paper, we use multinational research – which involves US researchers performing studies abroad – as a point of departure to examine mechanisms for collaborative IRB review. Such mechanisms can streamline IRB reviews for international studies, and may offer insights for an alternative approach to IRB review for purely domestic multisite research, as well. To shed light on these mechanisms, we review the relevant literature in order to identify the main problems arising in the course of IRB review of multinational research and summarize current initiatives both for purely domestic as well as international collaboration, and then we propose a heuristic that may be of use for assessing the effectiveness of a range of IRB collaborative strategies for addressing the identified problems, the goals of which are to reduce the regulatory burden of ethics review while enhancing the protection of human subjects.

Challenges that arise when protocols must satisfy the requirements and expectations of ethics review bodies in different countries have been extensively documented (Nuffield Council on Bioethics 1999; NBAC 2001; Glickman et al. 2009; Ravinetto et al. 2011). These challenges, which can delay and at times derail potentially beneficial research, can be categorized into five broad areas: 1) lack of expertise; 2) procedural challenges; 3) limited review capacities; 4) differences in review criteria; and 5) lack of trust.

Regardless of where they are located, IRBs have specific competencies (and incompetencies) based on resident expertise and research experiences. In general, US-based IRBs frequently fail to recognize differences between western norms and values and those of other countries and, as a result, do not appreciate the impact that these differences can have on how a protocol will be reviewed and how the research would be carried out in a different environment (London 2002; Macklin 2001). IRBs in developing countries may not have ready access to the scientific expertise needed to evaluate the risks and potential benefits of cutting-edge research, and may be highly dependent – expressly or implicitly -- upon US IRBs and scientific peer reviews to weigh in on such matters. In the end, protocols with study aims or consent and recruitment procedures that are insensitive to local culture or that fall outside national research agendas may be tabled or not approved by the local ethics review despite compliance with US regulatory requirements (White 1999; London 2002; Gilman and Garcia 2004; Dawson and Kass 2005; Dowdy 2006; Wahlberg et al. 2013). Complex protocols that are ethically sound but scientifically complex may require lengthy exchanges between a host-country IRB and the investigators before receiving the necessary approvals.

As shown by the increase in number of collaborative relationships (Table), US IRBs are finding ways to work together. However, consensus on procedural guidelines addressing what reviews are necessary, the order in which required reviews take place, and the process by which conflicting IRB determinations will be harmonized is generally missing in multinational reviews. In international settings, procedural challenges attributed to differing regulatory environments, difficulties accessing investigators to respond to ethics committee queries, and the lack of open channels of communication across reviewing IRBs to support resolution of minor issues can frequently result in significant delays (Nuffield Council on Bioethics 1999; Gilman and Garcia 2004; Musil et al. 2004; Rennie 2011).

Table 1.

Continuum of IRB Collaborative Mechanisms

| Mechanisms | Characteristics of Mechanism | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Reviews |

|

|

| Shared Information Systems |

|

|

| Open Communication |

|

|

| Availability of Consultants for Review |

|

|

| Division of Roles/Facilitated Review |

|

|

| Joint Review/Combined IRB |

|

|

Another area of difficulty arises from the often-huge disparity between ethical review “systems” themselves. Northern governments and research institutions have invested heavily in operational resources and professional staff trained in research ethics in support of IRBs. Despite significant international efforts to increase ethics capacity in Southern countries, ethics review systems in much of the world remain understaffed and under-resourced (Kass et al. 2007). Although highly professional ethics review processes operate in a number of developing countries, South Africa being one notable example, many northern IRBs have adopted a paternalistic approach, remaining unaware of local review capacities and loathe to defer any aspect of review to their counterparts in the developing world (Gilman and Garcia 2004).

Differences in review criteria and institutional goals can also impede the review of international protocols and increase the difficulties researchers confront in securing approvals. While most US-based IRBs base their reviews primarily on the Common Rule (DHHS 2012), FDA regulations (FDA 2012) and to a certain extent the ICH Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (ICH 1999), many IRBs in other parts of the world rely on other guidance documents, particularly the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA 2008) and the CIOMS Guidelines (CIOMS 2002; Macklin 2001; Wahlberg et al. 2013). Where US reviewers focus their attention on issues relating to autonomy, beneficence and nonmaleficence, non-US reviewers may be more concerned with issues of justice, protection of the vulnerable, standards of care, and post-trial access to benefits (Hyder et al. 2004). Adding further complexity, IRB functions in some countries reside in national research and development committees charged with the dual and potentially conflicting responsibilities of ensuring human subjects protections and promoting national research priorities (Kirigia et al. 2005).

In the current international research environment in which multiple IRBs act for the most part independently, with little understanding of each other’s activities, there is little room for task-sharing, reliance on each other’s expertise in particular areas of review, or guidance to researchers on how to navigate the review maze. This is fertile terrain for mistrust on both sides. US IRBs assume that host-country IRBs are unable to conduct adequate reviews, and the latter are skeptical that US IRBs will be sensitive to their national concerns or place the needs of a local population above the imperatives of the US research enterprise (Klitzman 2012).

A solution to many of these challenges resides in the willingness of institutions, and by extension their IRBs, to work collaboratively. Greater IRB collaboration is supported by various international guidelines. UNESCO (2005) and the World Health Organization (WHO 2000) encourage harmonized review procedures. CIOMS goes further, recommending that either review responsibilities be allocated amongst involved IRBs, entire review responsibility be deferred to one IRB by consensus, or that single review committees including representatives from each involved institution be created (CIOMS 2002). Inherent in all of these approaches is the potential for capacity-building. US-based IRBs can develop a better appreciation of host-country development and health priorities, cultural norms, and research settings, and host-country IRBs can directly garner knowledge regarding ethical review requirements and scientific methods and procedures (Ravinetto et al. 2011).

A number of mechanisms for multi-site ethics review have been proposed or implemented, mostly in the United States. These mechanisms appear in Table 1 as a continuum ranging from no collaboration to full shared review responsibilities. IRBs may work more closely together both for single reviews of large studies as well as for large shared research portfolios that are part of established long-term institutional partnerships. These mechanisms, which we recommend here for their ability to streamline and improve multinational research, will also contribute to more efficient and effective review in purely domestic collaborations. As shown in Table 1, purely domestic IRB collaborations are in place, and provide models on which other partnerships, domestic and multi-national, can be based.

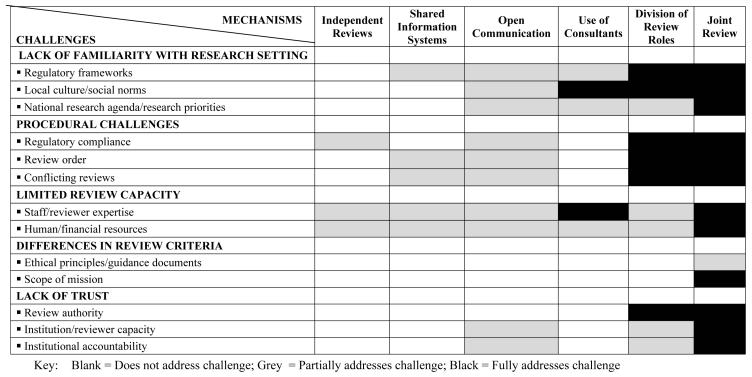

In Figure 1, we graphically present a framework for examining how directly and effectively each class of collaborative mechanism would address the specific challenges discussed above. In order to demonstrate how this framework might be employed, we include our subjective evaluations of the extent to which each of the identified collaborative mechanisms addresses the identified barriers, given the limitation that we are not examining any particular proposal. For example, the current system of independent reviews really fails to address these challenges (and, indeed, that’s why they have been identified as challenges in the literature reviewed above); we believe issues about regulatory compliance and expertise are partially addressed, in that iterative reviews by involved IRBs may provide education as a by-product, since each IRB may be exposed to requested changes made by others. On the other end of the spectrum, a joint review, involving members of 2 (or more) institutional IRBs involved in research, offers the opportunity for open discussion of standards, concerns, and values that, to our thinking, directly address all of the challenges, with the possible exception of differences in review criteria that may not be subject to negotiation.

Figure 1. Extent to Which Collaborative Mechanisms Address Challenges in Review of International Research.

This figure displays a heuristic method for considering the extent to which the collaborative mechanisms available for IRBs to work together address the array of challenges raised in the review of international research. Every method may help IRBs improve, but we posit that certain methods more directly address the challenges, as suggested by the darker shading of the intersecting boxes.

Likewise, shared information systems for managing protocols and opening other channels for direct IRB communications can help collaborating IRBs understand how they each work, what regulations and other sets of rules and norms they apply in making decisions, in what resources and expertise they bring to bear in making decisions, and making clear how review priority and potential conflicts are resolved. These mechanisms are a move toward transparency, but because much of the learning is indirect, secondary to actual processes and decisions being made by each IRB, we consider these to only partially address those challenges. In our judgment, as we move to more active collaboration, such as with involvement of consultants with in-country or specific research expertise, or assignment to each IRB of the roles for which they are most adept, the collaboration will more directly address the shortcomings that beset the current system.

Our evaluations may serve as a starting point for others undertaking their own assessment. No one mechanism will best suit the particularities of all multi-site research. Consideration of such mechanisms by institutions seeking to collaborate and establish IRB partnerships should address their particular needs, skills, experiences and circumstances, such as the availability of computing and communication technologies, time differences, language barriers, and the like, and make their own context-specific evaluations of the merits of available alternatives.

Critically, many of these mechanisms are new, and few have been fully evaluated. There is a clear need for increased assessment of existing and conceptual collaborative review strategies, including those in current use for review of multinational research. Ongoing evaluation should also be incorporated in future partnerships. Feedback on effectiveness as well as procedural or technical limitations will help IRBs, institutions and regulators assess how well these strategies address the challenges of multinational ethics review.

A one-size-fits-all solution to streamlined ethics review of research will not work. IRB collaboration that addresses the particularities of relationships, context, and complexity will. Open communication about challenges and capacities, combined with due consideration of what may work for any given situation, is a critical first step. A collaborative approach to strengthening ethics review of international research is essential if the global research enterprise is to build the inter-institutional, inter-IRB trust necessary to increase efficiency, satisfy regulatory requirements, and meet research objectives without sacrificing human subject safety or ignoring local norms and priorities.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center (S07-TW008836). It was adapted from a paper originally authored by Megan Kasimatis-Singleton as her thesis for the Masters in Bioethics degree. We thank Emma Meagher for comments.

References

- AIDS International Training and Research Program (AITRP) [accessed November 30, 2012];Dartmouth/MUHAS IRB Training Collaboration. 2012 http://www.dmsfogarty.org/component/content/article/49-irb.

- Al-Shahi R. Research ethics committees in the UK–the pressure is now on research and development departments. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2005;98:444–447. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.10.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett E. [accessed November 30, 2012];Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking: Summary of Comments. 2012 Feb 28; 2012. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp/mtgings/2012 Feb Mtg/anprmebartlett.pdf. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp/mtgings/2012 Feb Mtg/anprmsummaryebartlett.pdf.

- [accessed November 30, 2012];Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (BRANY) 2012 http://www.branyirb.com/

- Cave E, Holm S. New governance arrangements for research ethics committees: is facilitating research achieved at the cost of participants’ interest. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2002;28:318–321. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.5.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian MC, Goldberg JL, Killen J, et al. A central institutional review board for multi-institutional trials. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(18):1405–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205023461814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- College of Public Health Sciences and the Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Subjects. Health Sciences Group. Chulalongkorn University (ECCU) [accessed November 30, 2012];Regional Workshop: Capacity Building for the Ethical Review Committee of Health Sciences Research. 2010 http://whothailand.healthrepository.org/handle/123456789/603.

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) [accessed November 30, 2012];International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2002 http://www.cioms.ch/publications/layout_guide2002.pdf. [PubMed]

- Davis A. [accessed November 30, 2012];Alternative Models of IRB Review. 2011 http://primr.blogspot.com/2011/12/alternative-models-of-irb-review.html.

- Dawson L, Kass NE. Views of US researchers about informed consent in international collaborative research. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(6):1211–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdy DW. Partnership as an ethical model for medical research in developing countries: The example of the “Implementation Trial”. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2006;32(6):357–360. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.012955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Menikoff J. Reforming the regulations governing research with human subjects. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(12):1145–1150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1106942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman RH, Garcia HH. Ethics review procedures for research in developing countries: A basic presumption of guilt. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2004;171(3):248–249. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman SW, McHutchison JG, Peterson ED, et al. Ethical and scientific implications of the globalization of clinical research. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(8):816–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0803929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammatt ZH, Nishitani J, Heslin KC, et al. Partnering to harmonize IRBs for community-engaged research to reduce health disparities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(4 Suppl):8–15. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder AA, Wali SA, Khan AN, et al. Ethical review of health research: a perspective from developing country researchers. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2004;30:68–72. doi: 10.1136/jme.2002.001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijsselmuiden C, Marais D, Wassenaar D, Mokgatla-Moipolai B. Mapping African ethical review committee activity onto capacity needs: The MARC initiative and HRWeb’s interactive database of RECs in Africa. Developing World Bioethics. 2012;12(2):74–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use [accessed November 30, 2012];Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, E6. 1996 http://www.ich.org/products/guidelines/efficacy/article/efficacy-guidelines.html.

- IRBNet [accessed November 30, 2012];2012 http//www.irbnet.org/

- IRBshare [accessed November 30, 2012];2012 http://www.irbshare.org/

- Kass NE, Hyder AA, Ajuwon A, et al. The structure and function of research ethics committees in Africa: a case study. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040003. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirigia JM, Wambebe C, Baba-Moussa A. Status of national research bioethics committees in the WHO African region. BMC Medical Ethics. 2005;6:10–16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman RL. US IRBs confronting research in the developing world. Developing World Bioethics. 2012;12(2):63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London L. Ethical oversight of public health research: Can rules and IRBs make a difference in developing countries? American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(7):1079–1084. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin R. After Helsinki: unresolved issues in international research. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal. 2001;11(1):17–36. doi: 10.1353/ken.2001.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil C. Debate over Institutional Review Boards continues as alternative options emerge. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99(7):502–503. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil CM, Mutabaazi J, Walusimbi M, et al. Considerations for preparing collaborative international research: A Ugandan experience. Applied Nursing Research. 2004;17(3):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC) [accessed November 30, 2012];Ethical and policy issues in international research: Clinical trials in developing countries. 2001 Vol. 1 http://bioethics.georgetown.edu/nbac/human/overvol1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics [accessed November 30, 2012];The ethics of clinical research in developing countries. 1999 http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/sites/default/files/files/Clinical%20research%20in%20devel oping%20countries%20Discussion%20Paper.pdf.

- Philippine Council for Health Research and Development [accessed November 30, 2012];National Ethical Guidelines for Research. 2006 https://webapps.sph.harvard.edu/live/gremap/files/ph_natl_ethical_gdlns.pdf.

- Pittman K. [accessed May 1, 2013];Streamlining scientific and ethics review of multi-center health and medical research in Australia: Report to the National Health and Medical Research Council. 2007 Available at: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health-ethics/national-approach-single-ethical-review.

- Ravinetto R, Buvé A, Halidou T, et al. Double ethical review of North–South collaborative clinical research: hidden paternalism or real partnership? Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2011;16(4):527–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie S. [accessed November 30, 2012];The globalization of research ethics committees: Paternalism, ethical imperialism or partnership. 2011 http://globalbioethics.blogspot.com/2011/04/globalization-of-research-ethics.html.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) [accessed November 30, 2012];Universal declaration on bioethics and human rights. 2005 http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Advanced notice of proposed rulemaking: Human subjects research protections: Enhancing protections for research subjects and reducing burden, delay and ambiguity for investigators. Federal Register. 2011;76:44512–44531. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) [accessed November 30, 2012];Protection of Human Subjects. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45, Part 46. 2012 http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [accessed November 30, 2012];Guidance for industry: Using a centralized IRB review process in multicenter clinical trials. 2006 http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm127004.htm.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [accessed November 30, 2012];Protection of Human Subjects. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 50. 2012 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?cfrpart=50.

- United States National Institutes of Health. (NIH) Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Human Research Protections. Association of American Medical Colleges. American Society of Clinical Oncology [accessed November 30, 2012];Alternative Models of IRB Review (Workshop Summary Report) 2005 http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/archive/sachrp/documents/AltModIRB.pdf.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) National Institutes of Health. Association of American Medical Colleges. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Department of Veteran’s Affairs [accessed November 30, 2012];National Conference on Alternative IRB Models: Optimizing Human Subject Protection. 2006 https://www.aamc.org/download/75240/data/irbconf06rpt.pdf.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health [accessed November 30, 2012];Research portfolio online reporting tool (RePORT) Project Number 1S07TW008852-01. Enhanced collaborative ethics committee review of research proposals. 2012a http://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=8051319&icde=0.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health [accessed November 30, 2012];Research portfolio online reporting tool (RePORT) Project Number 1S07TW008850-01. Building a joint international IRB for Moi University and Indiana University. 2012b http://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=8051263.

- Vegoe E. [accessed November 30, 2012];Streamlining the IRB process. 2012 http://researchumn.com/2012/04/09/streamlining-the-irb-process/

- Wahlberg A, Rehmann-Sutter C, Sleeboom-Faulkner M, et al. From global bioethics to ethical governance of biomedical research collaborations. Social Science & Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.041. Published online April 3, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MT. Guidelines for IRB review of international collaborative medical research: A proposal. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 1999;27(1):87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1999.tb01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A, Grady C, Emanuel EJ. Regional ethics organizations for protection of human research participants. Nature Medicine. 2004;10(12):1283–1288. doi: 10.1038/nm1204-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) [accessed November 30, 2012];Operational guidelines for ethics committees that review biomedical research. 2000 http://www.who.int/tdr/publications/documents/ethics.pdf.

- World Medical Association (WMA) [accessed November 30, 2012];Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2008 http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/